Vasculitis

Dr MARWAN MAJEED IBRAHIM

CABM INTERNAL MEDICINE FICM PULMONARY MEDICINE

•

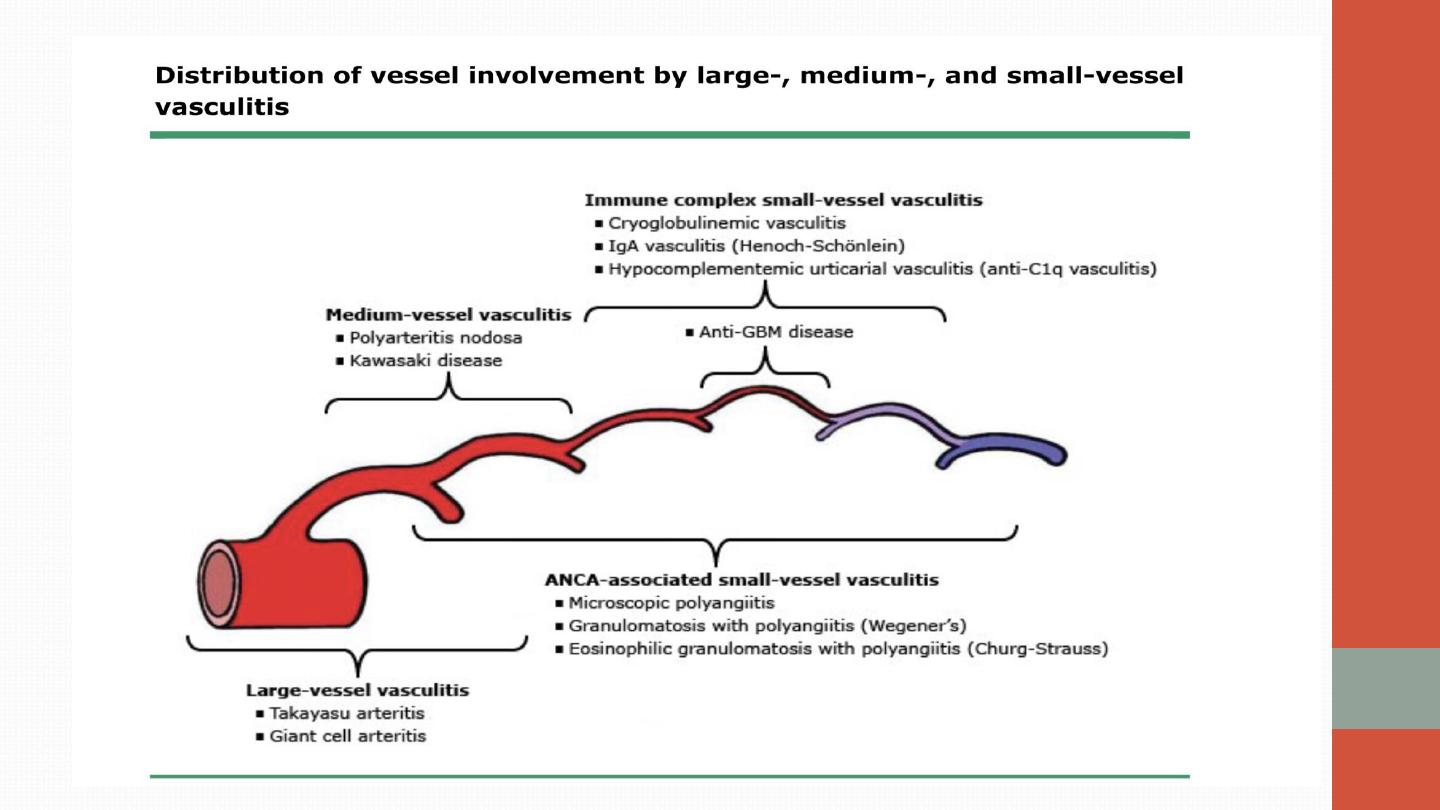

Vasculitis is characterised by inflammation and necrosis of blood-vessel

walls, with associated damage to skin, kidney, lung, heart, brain and

gastrointestinal tract. There is a wide spectrum of involvement and

severity, ranging from mild and transient disease affecting only the skin,

to life-threatening fulminant disease with multiple organ failure.

•

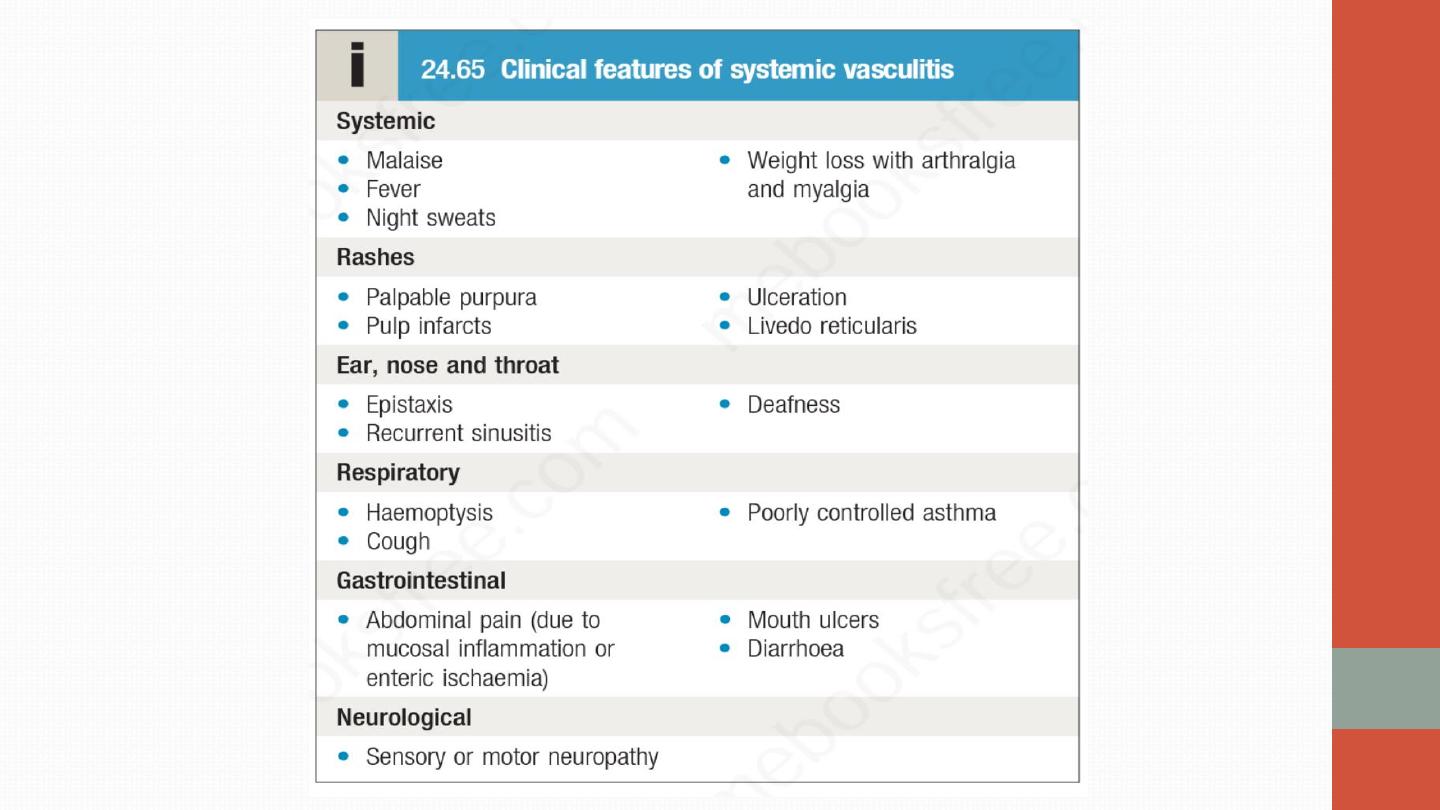

Systemic vasculitis should be considered in any patient with

fever,

weight loss, fatigue, evidence of multisystem involvement, rashes,

raised inflammatory markers and abnormal urinalysis.

Polyarteritis nodosa

•

Polyarteritis nodosa has a peak incidence between the ages of 40 and

50, with a male-to-female ratio of 2 : 1.

•

Hepatitis B is an important risk factor

•

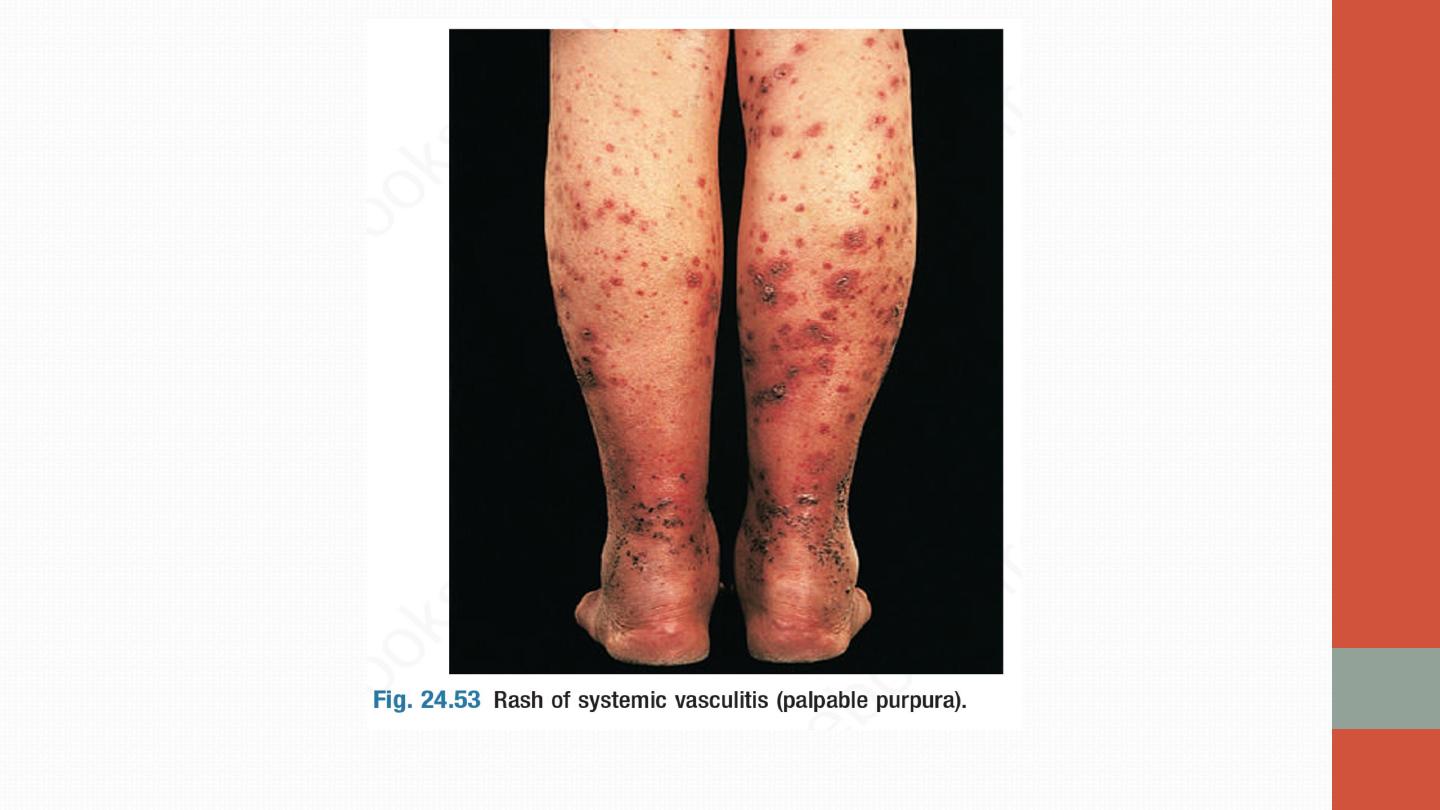

C/F: Presentation is with

fever, myalgia, arthralgia and weight loss, in

combination with manifestations of multisystem disease. The most

common skin lesions are palpable purpura

•

Pathological changes comprise necrotising inflammation and vessel

occlusion, and in 70% of patients arteritis of the vasa nervorum leads to

neuropathy, which is typically symmetrical and affects both sensory and

motor function.

•

PAN may be the only vasculitis syndrome that does not affect pulmonary

arteries nor does it cause glumerulonephritis!.

•

Severe hypertension and/or renal impairment may occur due to multiple

renal infarctions but glomerulonephritis is rare (in contrast to microscopic

polyangiitis).

•

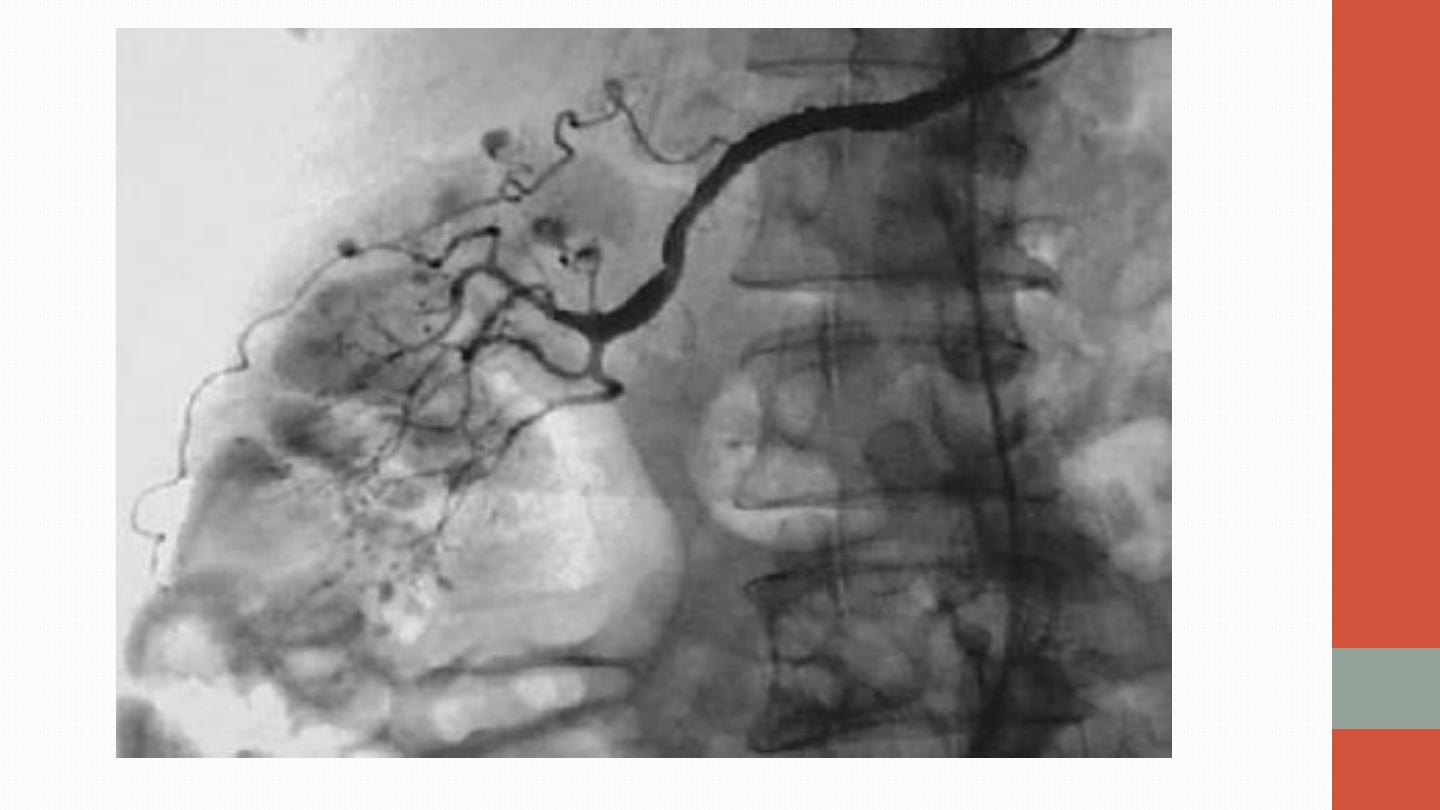

The diagnosis is confirmed by conventional or magnetic resonance

angiography, which shows multiple aneurysms and smooth narrowing

of mesenteric, hepatic or renal systems, or by muscle or sural nerve

biopsy

, which reveals the histological changes described above.

•

Treatment is with high-dose glucocorticoids and immunosuppressant.

Angiography of PAN

Giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia

rheumatica

•

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a granulomatous arteritis that affects any

large (including aorta) and medium-sized arteries. It is commonly

associated with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), which presents with

symmetrical, immobility-associated neck and shoulder girdle pain and

stiffness.

•

Since many patients with GCA have symptoms of PMR, and many

patients with PMR go on to develop GCA if untreated, many

rheumatologists consider them to be different manifestations of the

same underlying disorder.

•

Both diseases are rare under the age of 60 years. The average age at

onset is 70, with a female-to-male ratio of about 3 : 1.

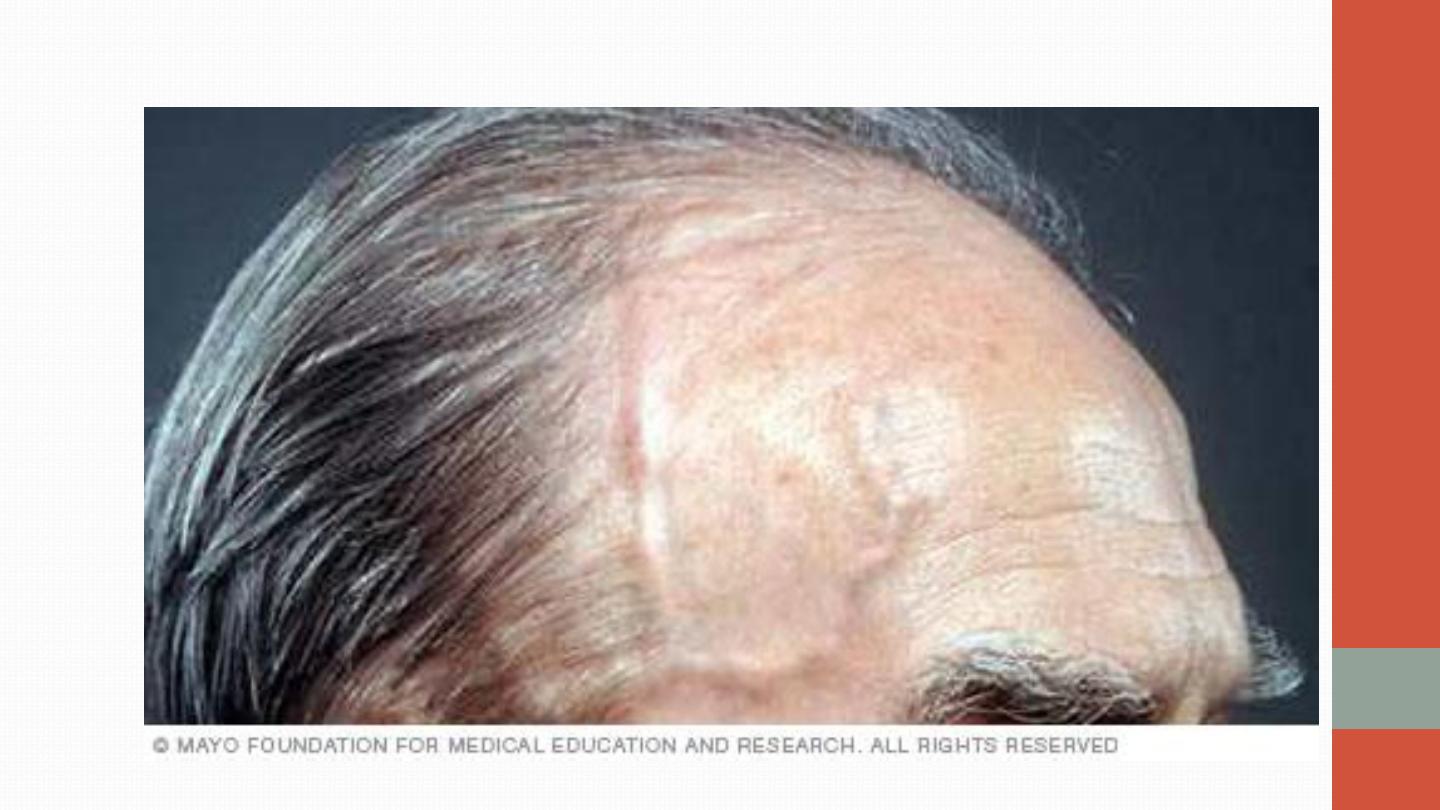

TEMPORAL ARTERITIS

•

C/F:

•

The cardinal symptom of GCA is headache, which is often localised to

the temporal or occipital region and may be accompanied by scalp

tenderness. Jaw pain develops in some patients, brought on by

chewing or talking. Visual disturbance can occur (most specifically

amaurosis) and a catastrophic presentation is with blindness in one eye

due to occlusion of the posterior ciliary artery. On fundoscopy, the

optic disc may appear pale and swollen with haemorrhages.

•

Rarely, neurological involvement may occur, with transient ischaemic

attacks, brainstem infarcts and hemiparesis.

•

In GCA, constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss, fatigue, malaise

and night sweats, are common.

With PMR, there may be stiffness and

painful restriction of active shoulder movements on waking. Muscles are

not otherwise tender, and weakness and muscle-wasting are absent.

•

Ix:

•

The typical laboratory abnormality is an

elevated ESR

, often with a

normochromic, normocytic anaemia. CRP may also be elevated and

abnormal liver function can occur.

More objective evidence for GCA

should be obtained whenever possible.

There are three investigations to

consider: 1- temporal artery biopsy, 2- ultrasound of the temporal

arteries . Diagnostic yield is highest with multiple biopsies and multiple

section analysis (to detect ‘skip’ lesions). A negative biopsy does not

exclude the diagnosis. On ultrasound examination, affected temporal

arteries show a ‘halo’ sign. A strongly positive 3- 19FDG PET scan is

highly specific but sensitivity is low.

•

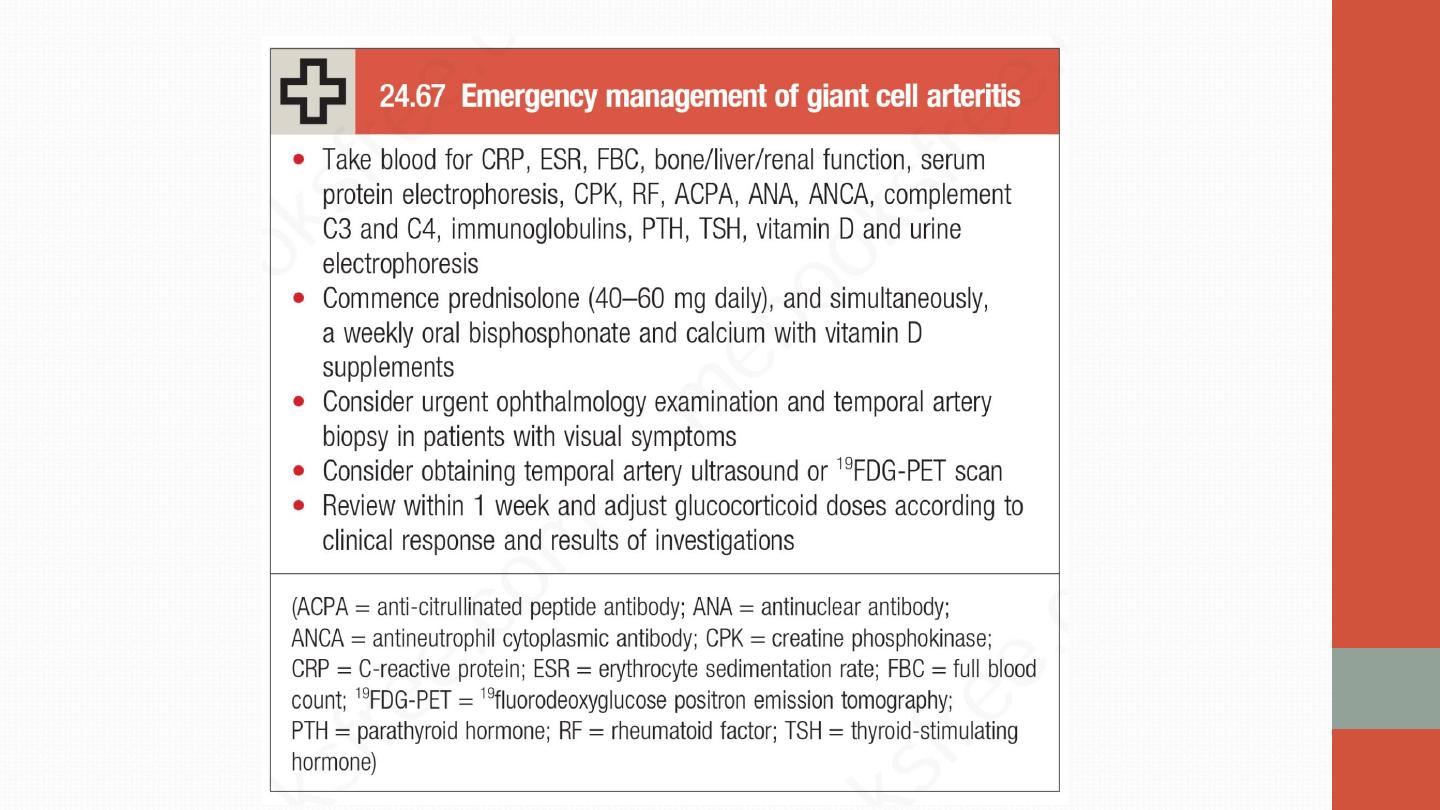

Management

•

Prednisolone

should be commenced urgently in suspected GCA because

of the risk of visual loss.

Response is dramatic

, such that symptoms will

completely resolve within 48–72 hours of starting therapy in virtually all

patients. It is customary to use higher doses in GCA (60–80 mg prednisolone)

than in PMR (15–20 mg), although the evidence base for this is weak. In both

conditions, the glucocorticoid dose should be progressively reduced, guided

by symptoms and ESR, with the aim of reaching a dose of 10–15 mg by about

8 weeks.

•

Most patients need glucocorticoids for an average of 12–24 months.

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with

polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss syndrome)

•

small-vessel vasculitis. It is associated with

eosinophilia

. Some patients

have a prodromal period for many years, characterised by

allergic rhinitis,

nasal polyposis and late-onset

asthma

that is often difficult to control.

The typical acute presentation is with a triad of skin lesions (purpura or

nodules), asymmetric mononeuritis multiplex and eosinophilia.

Pulmonary infiltrates and pleural or pericardial effusions due to serositis

may be present. Up to 50% of patients have abdominal symptoms provoked

by mesenteric vasculitis.

•

Patients with active disease have raised levels of ESR and CRP and an

eosinophilia

.

Although antibodies to MPO (pANCA) or PR3(cANCA) can be

detected in up to 60% of cases.

•

Biopsy of an affected site reveals a small-vessel vasculitis with eosinophilic

infiltration of the vessel wall.

•

Management is with high-dose glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide,

followed by maintenance therapy with low-dose glucocorticoids and

azathioprine, methotrexate or MMF.

Henoch–Schönlein purpura

•

URTI and streptococcal infection often precede HSP .

•

is a small-vessel vasculitis caused by immune complex deposition following

an infectious trigger.

•

It is predominantly a disease of children and young adults. The usual

presentation is with purpura over the buttocks and lower legs, accompanied

by abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding and arthralgia. Nephritis can

also occur and may present up to 4 weeks after the onset of other symptoms.

Biopsy of affected tissue shows a vasculitis with IgA deposits in the vessel

wall.

•

It is usually a self-limiting disorder that settles spontaneously without

specific treatment

•

Glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive therapy may be required in patients

with more severe disease, particularly in the presence of nephritis.

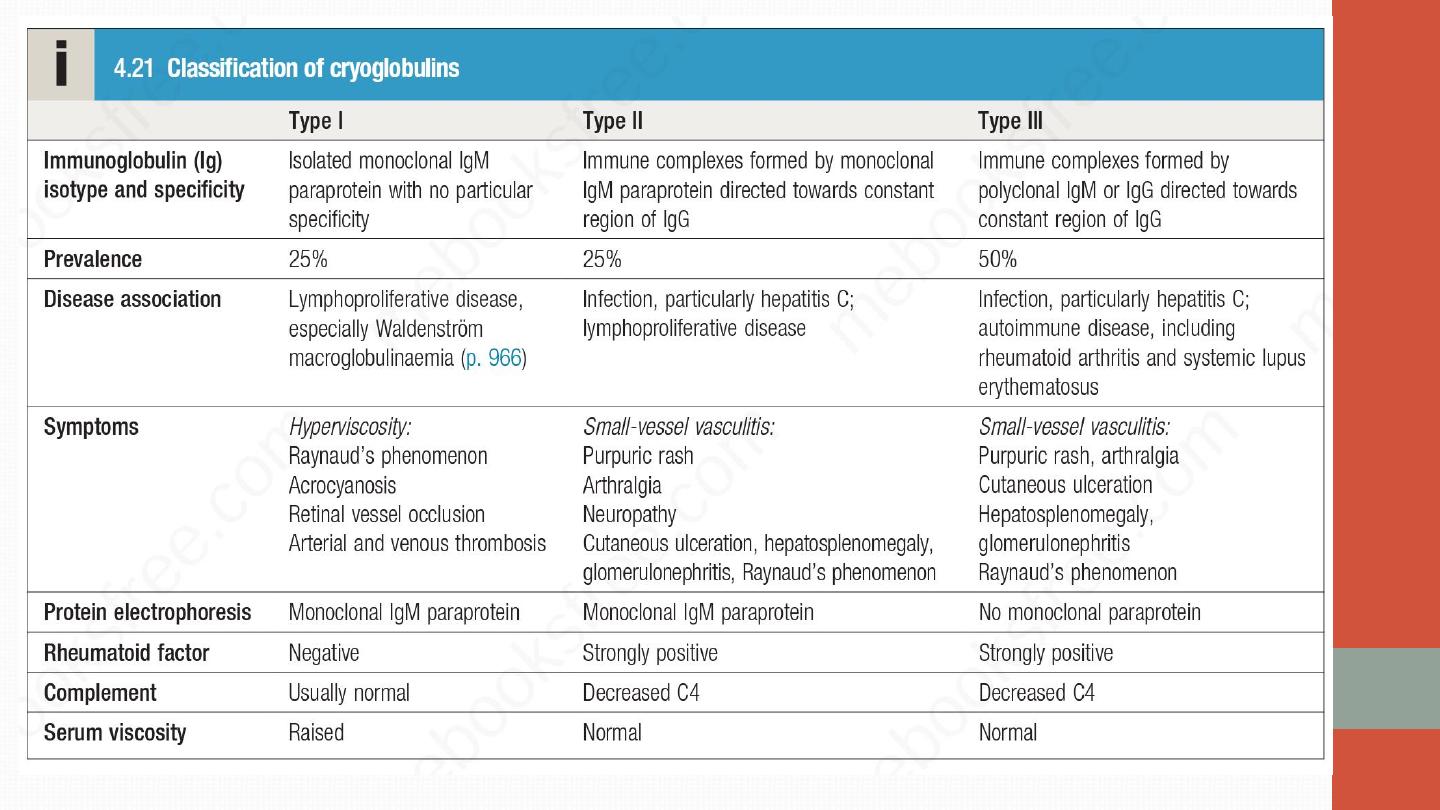

Cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis

•

This is a small-vessel vasculitis that occurs when immunoglobulins precipitate

out in the cold. Cryoglobulins are classified into three types. Types II and III

are associated with vasculitis. The typical presentation is with a vasculitic

rash over the lower limbs, arthralgia, Raynaud’s phenomenon and

neuropathy.

Some cases are secondary to hepatitis C

infection and others

are associated with other autoimmune diseases. Affected patients should be

screend for evidence of hepatitis B and C infection, and if the results are

positive, these should be treated appropriately. There is no consensus as to

how best to treat cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis in the absence of an obvious

trigger. Glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive therapy are often used

empirically but their efficacy is uncertain. In severe cases, plasmapheresis can

be considered

Antiglomerular membrane disease /

GOODPASTURE syndrome

•

The clinical presentations include a rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis

without lung involvement (termed "anti-GBM disease") or a rapidly

progressive glomerulonephritis with pulmonary hemorrhage (Goodpasture

syndrome). Goodpasture's has a bimodal age distribution: 20-30 years (M > F)

and 60-70 years (F > M). Smoking has a strong correlation with alveolar

hemorrhage, especially in young males.

•

Diagnosis anti-GBM disease by measuring anti-GBM antibodies in the serum

and with renal and/or lung biopsy, which will demonstrate evidence of the

anti-GBM antibodies on immunofluorescence. About 15% of patients who

are anti-GBM+ also are ANCA + and can have symptoms of systemic

vasculitis.

•

Treatment involves plasmapheresis to remove circulating anti-GBM

antibodies and immunosuppression with glucocorticoids and

cyclophosphamide to inhibit further autoantibody formation.

•

Remember the

pulmonary-renal syndromes

(rheumatic diseases that can

cause alveolar hemorrhage and glomerulonephritis):

•

• Goodpasture syndrome

•

• CTD: SLE, RA, PM or DM, PSS

•

• Systemic vasculitis: GPA, MPA, EGPA, HSP, Churg-Strauss

•

• Drug-induced: propylthiouracil (PTU)

•

• Behcet disease

•

• Cryoglobulinemia

Behçet’s disease

•

This is a vasculitis of unknown aetiology that characteristically targets

small arteries and venules. It is rare in Western Europe but more common

in ‘Silk Route’ countries, around the Mediterranean and in Japan, where

there is a strong association with HLA-B51.

•

C/F:

•

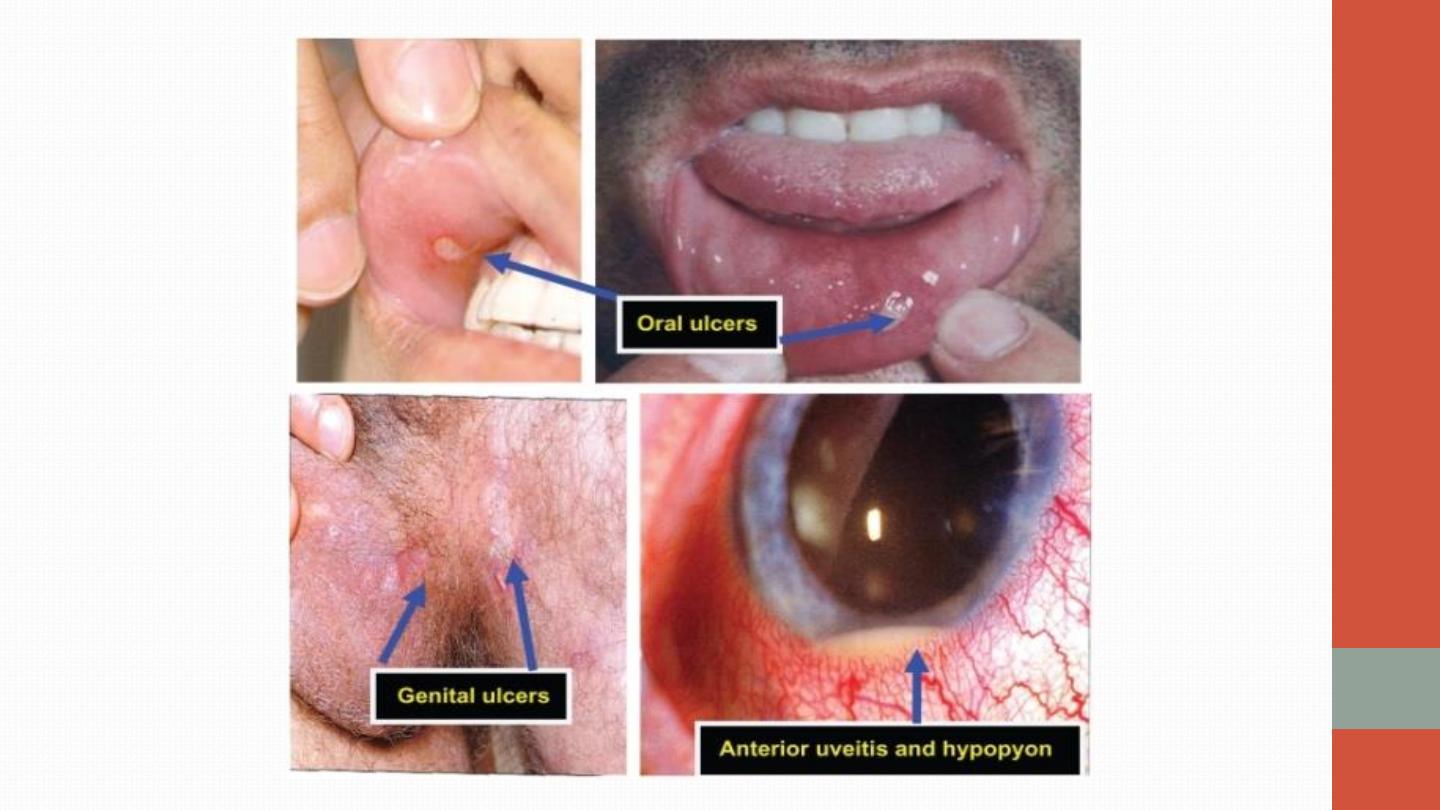

Oral ulcers are universal. Unlike aphthous ulcers, they are usually deep and

multiple, and last for 10–30 days. Genital ulcers are also a common problem,

occurring in 60–80% of cases. The usual skin lesions are erythema nodosum

or acneiform lesions but migratory thrombophlebitis and vasculitis also

occur. Ocular involvement is common and may include anterior or posterior

uveitis or retinal vasculitis

•

Brain stem , although the meninges, hemispheres and cord can also be

affected, causing pyramidal signs, cranial nerve lesions, brainstem

symptoms or hemiparesis. Recurrent thromboses also occur.

•

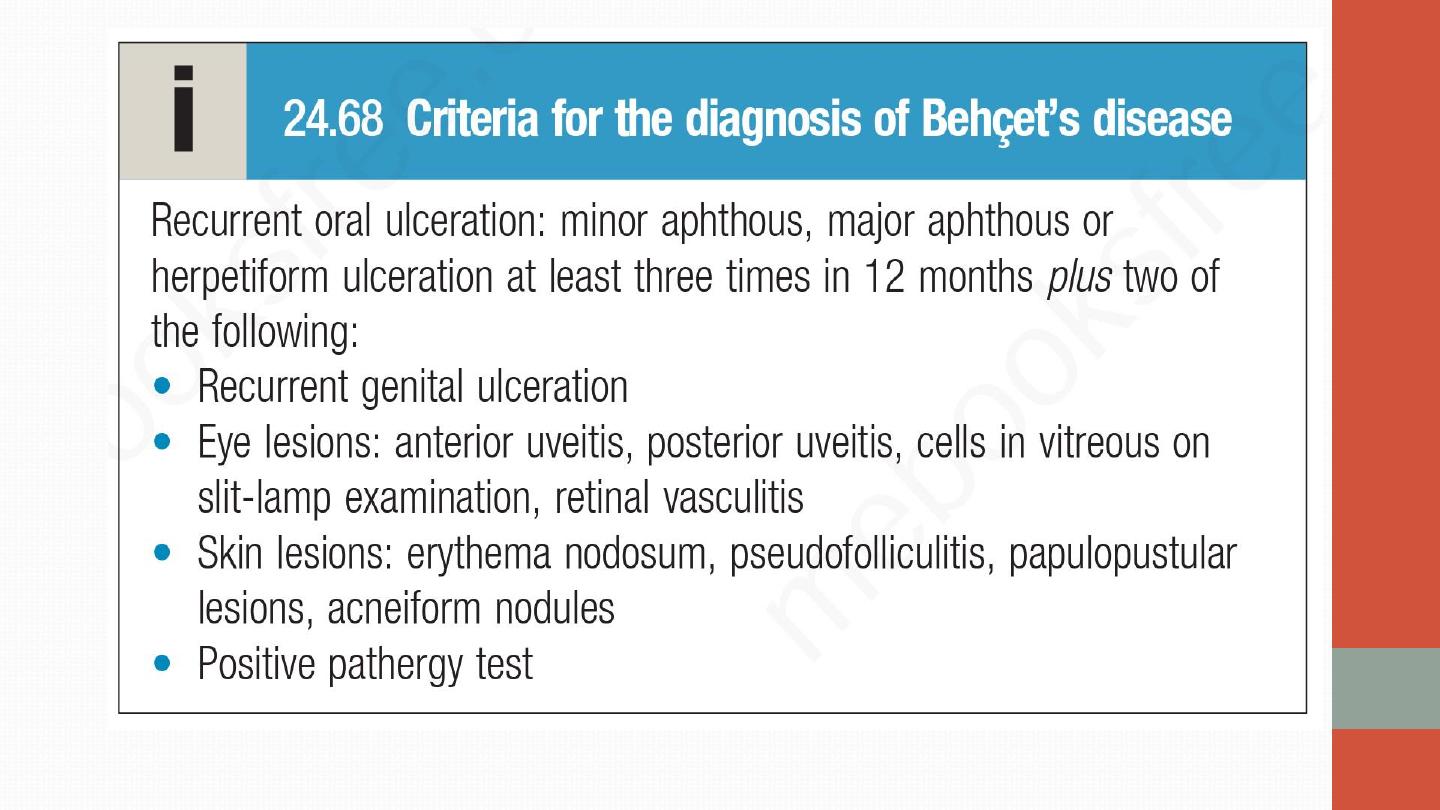

Diagnosis is clinical- the pathergy test, which involves pricking the skin

with a needle and looking for evidence of pustule development within

48 hours.

•

Oral ulceration can be managed with topical glucocorticoid preparations

(soluble prednisolone mouthwashes, glucocorticoid pastes). Colchicine can

be effective for erythema nodosum and arthralgia. Thalidomide is very

effective for resistant oral and genital ulceration but is teratogenic and

neurotoxic.

Glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants are indicated for

uveitis and neurological disease.

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-

associated vasculitis

•

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a life-

threatening disorder characterised by inflammatory infiltration of small

blood vessels, fibrinoid necrosis and the presence of circulating antibodies

to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA).

•

The main two types: Microscopic polyangiitis & granulomatosis with

polyangiitis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

•

(Formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis) is characterised by

granuloma formation, mainly affecting the nasal passages, airways and

kidney.

A minority of patients present with glomerulonephritis. The most

common presentation of granulomatosis with polyangiitis is with

epistaxis, nasal crusting and sinusitis, but haemoptysis and mucosal

ulceration may also occur. Deafness may be a feature due to inner ear

involvement, and proptosis may occur because of inflammation of the

retro-orbital tissue . This causes diplopia due to entrapment of the extra-

ocular muscles, or loss of vision due to optic nerve compression.

Untreated nasal disease ultimately leads to destruction of bone and

cartilage (Saddle nose). Migratory pulmonary infiltrates and cavitating

nodules occur in 50% of patients (as seen on high-resolution CT of

lungs).

WEGENERS DISEASE

•

Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis are usually proteinase-3

(PR3) antibody-positive

.

•

Patients with active disease usually have a leucocytosis with elevated

CRP, ESR and PR3.

•

Imaging of the upper airways or chest with MRI can be useful in

localising abnormalities

•

the diagnosis should be confirmed by biopsy of the kidney or lesions

in the sinuses and upper airways.

•

Management for organ-threatening or acute–severe disease is with high-

dose glucocorticoids (e.g. daily pulse intravenous methylprednisolone

0.5–1 g for 3 days, then oral prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg) and intravenous

cyclophosphamide (e.g. 0.5–1 g every 2 weeks for 3 months), followed

by maintenance therapy with lower-dose glucocorticoids and

azathioprine, methotrexate or MMF. Plasmapheresis should be

considered for fulminant lung disease. Rituximab may be used.

Glucocorticoids and methotrexate are an effective combination for

treating limited AAV where there is indolent sinus, lung or skin disease.

Microscopic polyangiitis

•

Necrotising small-vessel vasculitis found with rapidly progressive

glomerulonephritis, often in association with alveolar haemorrhage.

Cutaneous and gastrointestinal involvement is common and other

features include neuropathy (15%) and pleural effusions (15%). Patients

are usually myeloperoxidase (MPO) antibody-positive ie, pANCA + ve.

•

Treatment with steroid , immunosuppressant & rituximab.

Takayasu arteritis

•

Takayasu arteritis affects the aorta, its major branches and occasionally the

pulmonary arteries. The typical age at onset is 25–30 years, with an 8 : 1

female-to-male ratio. It has a worldwide distribution but is most common

in Asia.

•

It presents with claudication, fever, arthralgia and weight loss. Clinical

examination may reveal loss of pulses, bruits, hypertension and aortic

incompetence. Investigation will identify an acute phase response and

normocytic, normochromic anaemia but the diagnosis is based on

angiography, which reveals coarctation, occlusion and aneurysmal dilatation.

Treatment is with high-dose glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants.

Kawasaki disease

•

Kawasaki disease is a vasculitis that mostly involves the coronary

vessels. It presents as an acute systemic disorder, usually affecting

children under 5 years. It occurs mainly in Japan and other Asian

countries.

•

Presentation is with fever, generalised rash, including palms and soles,

inflamed oral mucosa and conjunctival injection resembling a viral

exanthem. The cause is unknown but is thought to be an abnormal

immune response to an infectious trigger. Cardiovascular complications

include coronary arteritis, leading to myocardial infarction, transient

coronary dilatation, myocarditis, pericarditis, peripheral vascular

insufficiency and gangrene. Treatment is with aspirin (5 mg/kg daily for

14 days) and IVIg (400 mg/kg daily for 4 days).

Adult-onset Still’s disease

•

Adult-onset Still’s disease is a rare systemic inflammatory disorder of

unknown cause, possibly triggered by infection; it is similar to sJIA. It

presents with intermittent high grade fever, rash and arthralgia, and has

been associated with pregnancy and the postpartum period and with

high levels of IL-18.

•

Splenomegaly, hepatomegaly and lymphadenopathy may be present.

Investigations typically provide evidence of an acute phase response,

with a markedly elevated serum ferritin.

•

Tests for RF and ANA are negative

•

Most patients respond to glucocorticoids but immunosuppressants,

such as azathioprine or MMF, can be added when response is

inadequate. Canakinumab or anakinra can be used for patients with

resistant disease.