Common Viral

Infections

DONE BY DR MARWAN MAJEED IBRAHIM

CABM INTERNAL MEDICINE FICM RESPIRATORY

MEDICINE

Measles

Clinical features

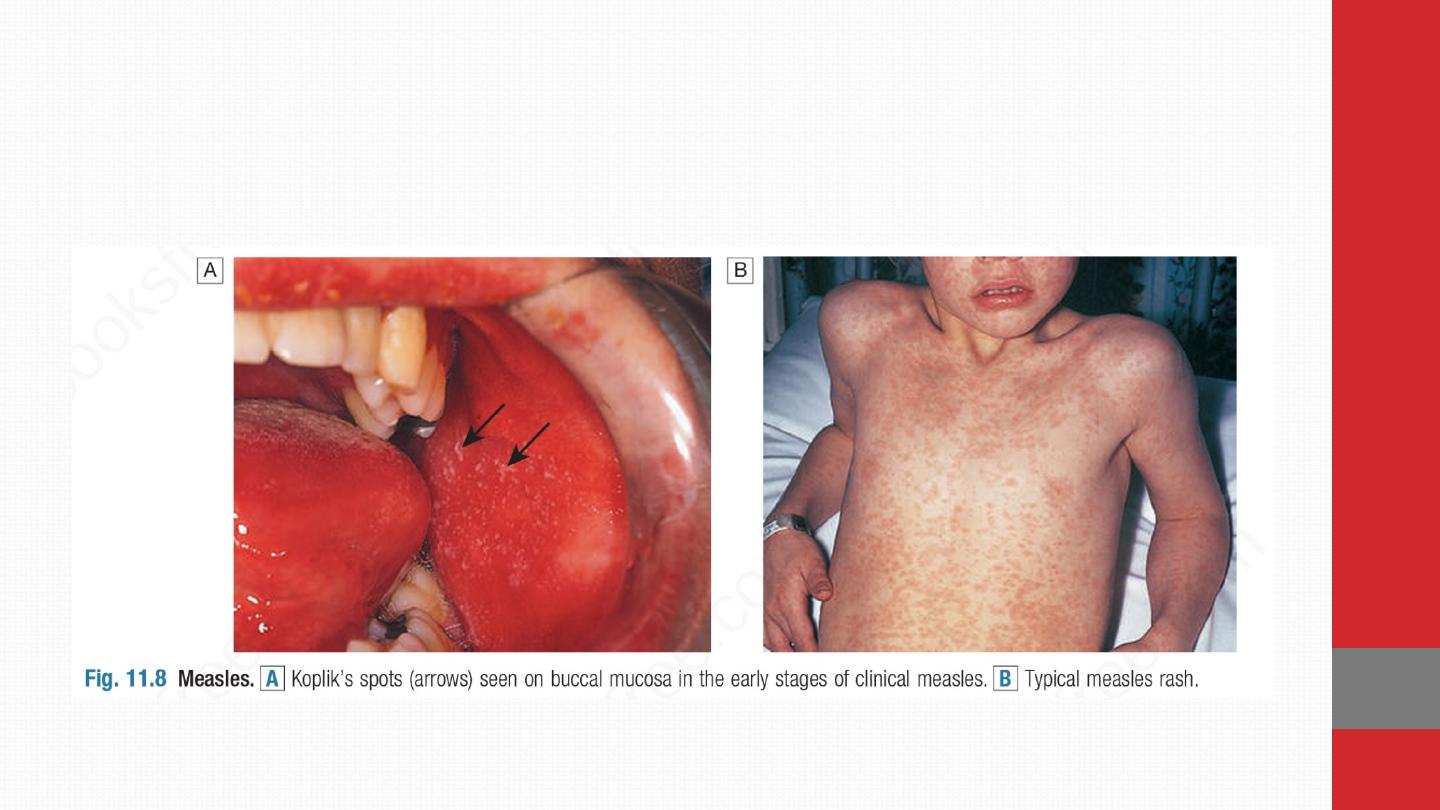

Infection is by respiratory droplets with an incubation period

of 6–19 days. A prodromal illness occurs, 1–3 days before the

rash, with upper respiratory symptoms, conjunctivitis and the

presence of the pathognomonic Koplik’s spots: small white

spots surrounded by erythema on the buccal mucosa. As

natural antibody develops, the maculopapular rash appears,

spreading from the face to the extremities . Generalised

lymphadenopathy and diarrhoea are common.

Complications are more common in older children and adults,

and include otitis media, bacterial pneumonia, transient

hepatitis, pancreatitis and clinical encephalitis

(approximately 0.1% of cases). A rare late complication is

subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), which occurs

up to 7 years after infection.

Diagnosis is clinical (although this has become unreliable in

areas where measles is no longer common) and by detection of

antibody (serum immunoglobulin M (IgM), seroconversion or

salivary IgM).

Meaes is a serious disease in the malnourished, vitamin

deficient or immunocompromised, in whom the typical

rash may be missing and persistent infection with a

giant cell pneumonitis or encephalitis may occur.

In

tuberculosis infection, measles suppresses cell-mediated

immunity and may exacerbate disease; for this reason,

measles vaccination should be deferred until after

commencing antituberculous treatment

. Measles does not

cause congenital malformation but may be more severe

in pregnant women.

Mortality clusters at the extremes of age, averaging 1 :

1000 in developed countries and up to 1 : 4 in developing

countries.

Death usually results from a bacterial

superinfection, occurring as a complication of measles:

most often pneumonia, diarrhoeal disease or

noma/cancrum oris, a gangrenous stomatitis. Death may

also result from complications of measles encephalitis

.

Management and prevention Normal immunoglobulin

attenuates the disease in the immunocompromised (regardless of

vaccination status) and in non-immune pregnant women, but

must be given within 6 days of exposure. Vaccination can be

used in outbreaks and vitamin A may improve the

outcome in uncomplicated disease. Antibiotic therapy is

reserved for bacterial complications. All children aged 12–15

months should receive measles vaccination (as combined

measles, mumps and rubella (MMR), a live attenuated vaccine), and

a further MMR dose at age 4 years

Rubella (German measles)

Clinical features Rubella is spread by respiratory droplet,

with infectivity from up to 10 days before to 2 weeks after the

onset of the rash. The incubation period is 15–20 days. In

childhood, most cases are subclinical, although clinical features

may include fever, maculopapular rash spreading from the

face, and lymphadenopathy. Complications are rare but

include thrombocytopenia and hepatitis. Encephalitis and

haemorrhage are occasionally reported. In adults, arthritis

involving hands or knees is relatively common mainly in women.

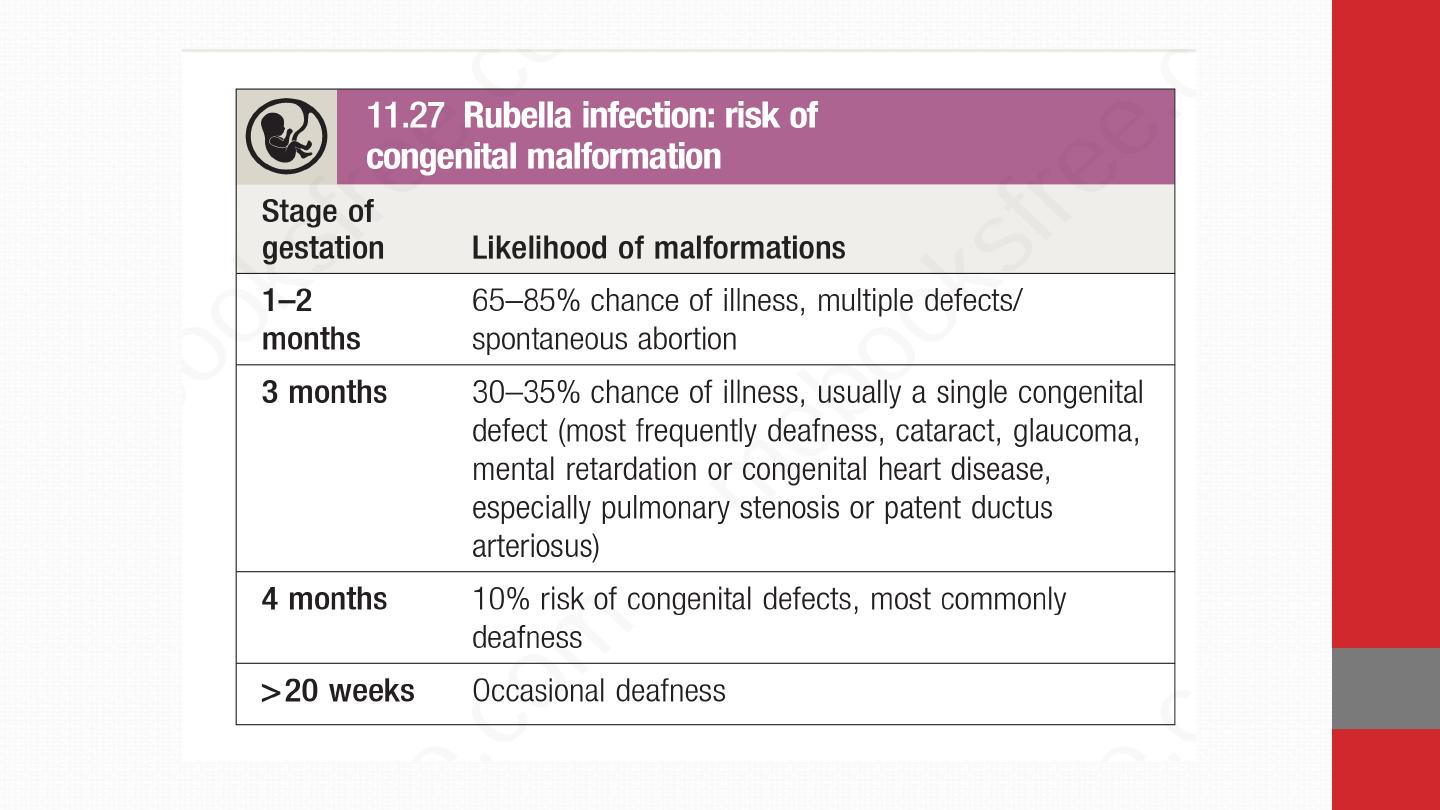

If transplacental infection takes place in the first

trimester or later, persistence of the virus is likely and

severe congenital disease may result . Even if normal at

birth, the infant has an increased incidence of other

diseases developing later, e.g. diabetes mellitus

Diagnosis Laboratory confirmation of rubella is required if

there has been contact with a pregnant woman. This is

achieved either by detection of

rubella IgM in serum or by

IgG seroconversion. In the exposed pregnant woman,

absence of rubella-specific IgG confirms the potential for

congenital infection

.

Prevention All children should be immunised with MMR vaccine.

Congenital rubella syndrome may be controlled by testing

women of childbearing age for rubella antibodies and

offering vaccination if seronegative

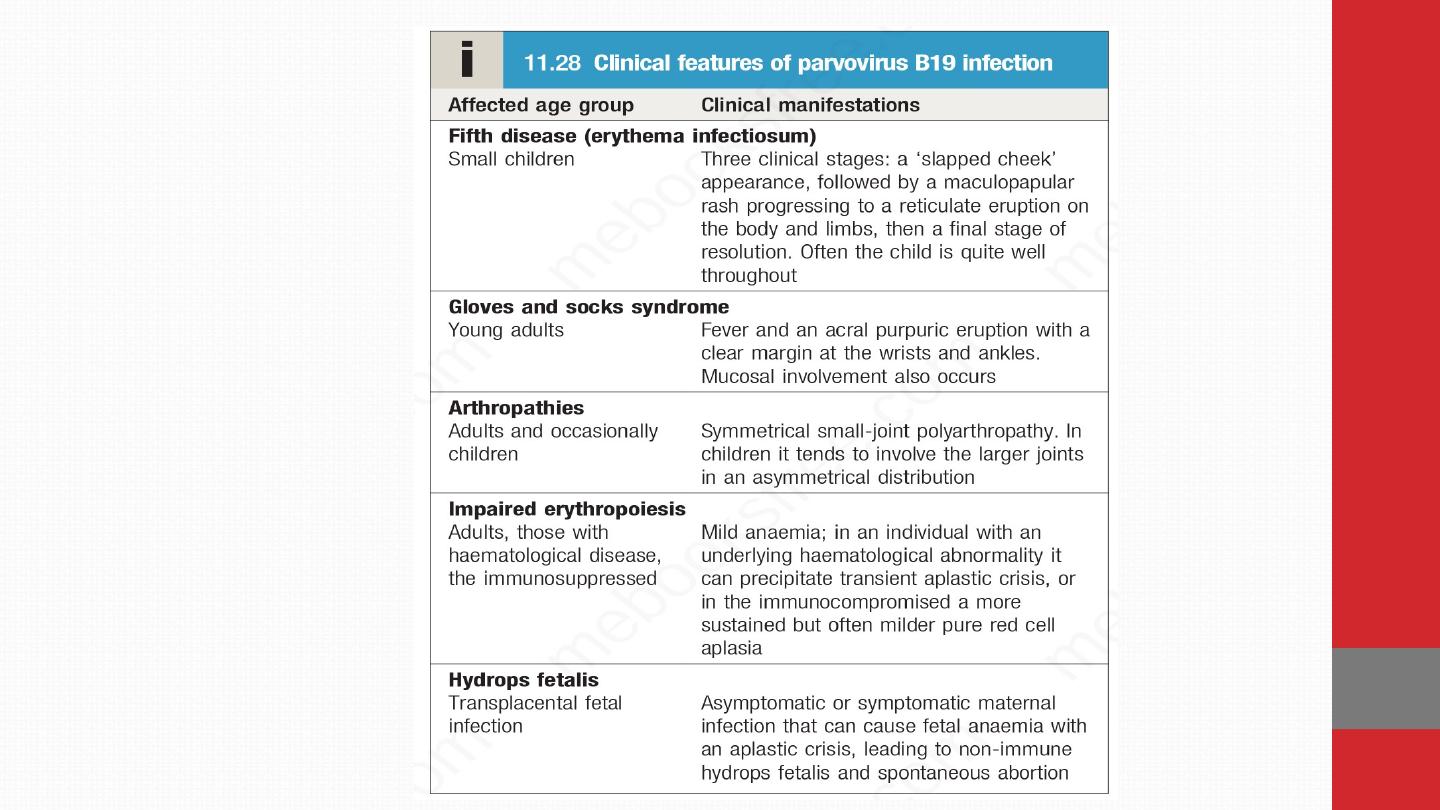

Parvovirus B19

Parvovirus B19 causes exanthem and other clinical syndromes. Some

50% of children and 60–90% of adults are seropositive.

Clinical features Many infections are subclinical. Clinical

manifestations result after an incubation period of 14–21 days. The

classic exanthem (erythema infectiosum) is preceded by a

prodromal fever and coryzal symptoms. A ‘slapped cheek’

rash is characteristic but the rash is very variable . In adults,

polyarthropathy is common. Infected individuals have a transient

block in erythropoiesis for a few days, which is of no clinical

consequence, except in individuals with increased red cell turnover

due to haemoglobinopathy or haemolytic anaemia.

These individuals develop an acute anaemia that may be severe

(transient aplastic crisis). Erythropoiesis usually recovers

spontaneously after 10–14 days. Immunocompromised individuals,

including those with congenital immunodeficiency or AIDS, can

develop a more sustained block in erythropoiesis in response to the

chronic viraemia that results from their inability to clear the infection.

Infection during the first two trimesters of pregnancy can

result in intrauterine infection and impact on fetal bone

marrow; it causes 10–15% of non-immune (non-Rhesus-

related) hydrops fetalis, a rare complication of pregnancy.

Diagnosis IgM to parvovirus B19 suggests recent infection but may

persist for months Detection of parvovirus B19 DNA in blood is

particularly

useful

in

immunocompromised patients.

Giant

pronormoblasts or haemophagocytosis may be demonstrable

in the bone marrow.

Management Infection is usually self-limiting. Symptomatic relief for

arthritic symptoms may be required.

The pregnancy should be closely monitored by ultrasound scanning,

so that hydrops fetalis can be treated by fetal transfusion

Chickenpox (VARICELLA)

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) happens usually in childhood, which may

reactivate in later life. VZV is spread by aerosol and direct contact. It

is highly infectious to non-immune individuals. Disease in children

is usually well tolerated. Manifestations are more severe in

adults, pregnant women and the immunocompromised.

Clinical features The incubation period is 11–20 days, after which a

vesicular eruption begins , often on mucosal surfaces first, followed

by rapid dissemination in a centripetal distribution (most dense

on trunk and sparse on limbs). New lesions occur every 2–4 days and

each crop is associated with fever. The rash progresses from small

pink macules to vesicles and pustules within 24 hours. Infectivity

lasts from up to 4 days (but usually 48 hours) before the

lesions appear until the last vesicles crust over. Due to intense

itching, secondary bacterial infection from scratching is the most

common complication of primary chickenpox. Self-limiting

cerebellar ataxia and encephalitis are rare complications.

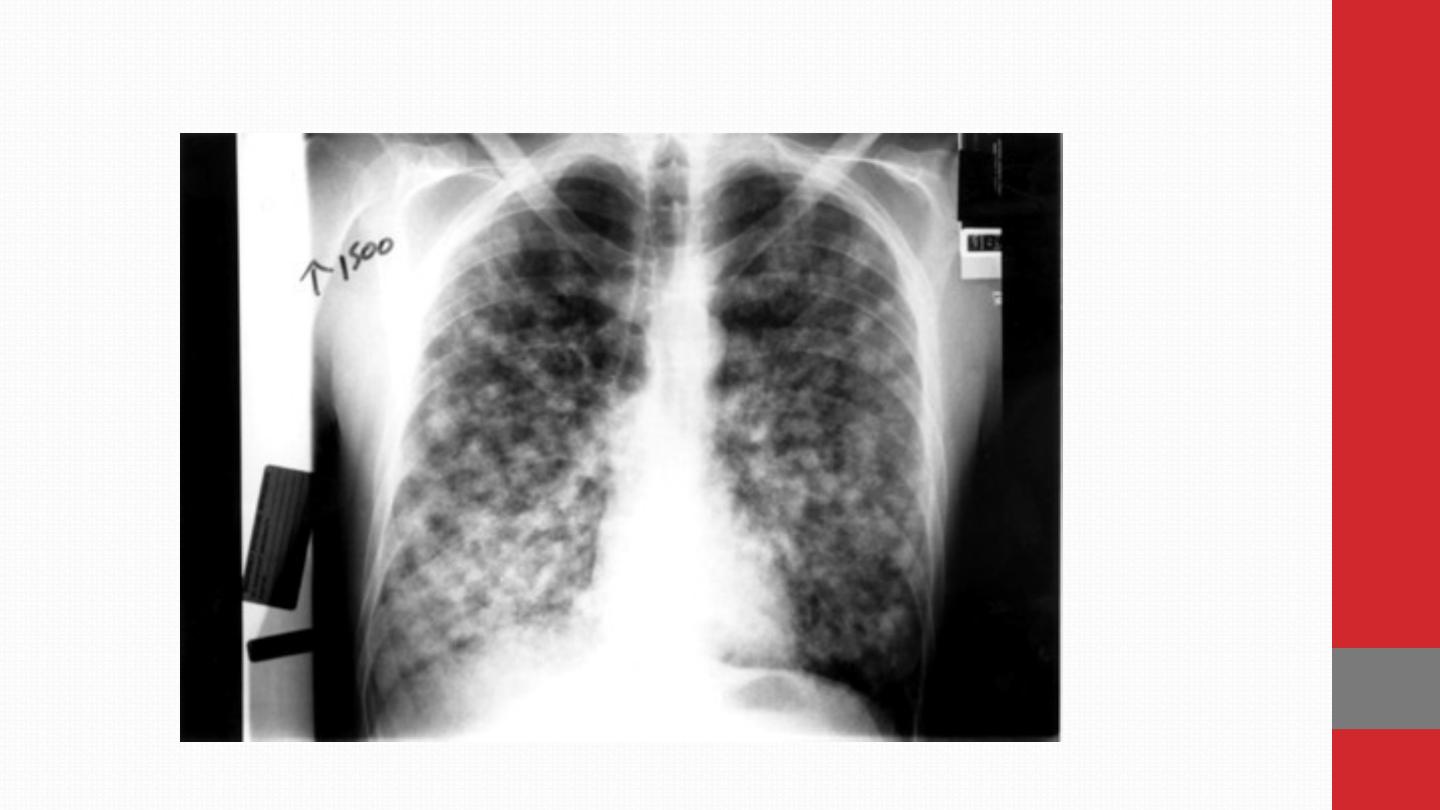

Adults, pregnant women and the immunocompromised are at

increased risk of visceral involvement, which presents as

pneumonitis, hepatitis or encephalitis. Pneumonitis can be

fatal and is more likely to occur in smokers. Maternal infection in

early pregnancy carries a 3% risk of neonatal damage with

developmental abnormalities of eyes, CNS and limbs. Chickenpox

within 5 days of delivery leads to severe neonatal varicella with

visceral involvement and haemorrhage. Diagnosis is clinical.

Management and prevention The benefits of antivirals for

uncomplicated primary VZV infection in children are marginal,

shortening the duration of rash by only 1 day, and treatment is not

normally

required.

Antivirals

are,

however,

used

for

uncomplicated chickenpox in adults when the patient

presents within 24–48 hours of onset of vesicles, in all

patients with complications, and in those who are

immunocompromised, including pregnant women, regardless

of duration of vesicles . More severe disease, particularly in

immunocompromised hosts, requires initial parenteral therapy.

Immunocompromised patients may have prolonged viral shedding

and may require prolonged treatment until all lesions crust over.

Human VZ immunoglobulin (VZIG) is used to attenuate

infection in people who have had significant contact with VZV,

are susceptible to infection (i.e. have no history of chickenpox

or shingles and are seronegative for VZV IgG) and are at risk

of severe disease (e.g. immunocompromised or pregnant)

.

Ideally, VZIG should be given within 7 days of exposure, but it may

attenuate disease even if given up to 10 days afterwards

.

Susceptible contacts who develop severe chickenpox after

receiving VZIG should be treated with aciclovir.

Shingles (herpes zoster)

After initial infection, VZV persists in latent form in the dorsal

root ganglion of sensory nerves and can reactivate in later

life .

Clinical features

Burning discomfort occurs in the affected

dermatome following reactivation and discrete vesicles

appear 3–4 days later

. This is associated with a brief viraemia,

which

can

produce

distant

satellite

‘chickenpox’

lesions.

Occasionally, paraesthesia occurs without rash (‘zoster sine

herpete’).

Severe disease, a prolonged duration of rash,

multiple dermatomal involvement or recurrence suggests

underlying immune deficiency, including HIV. Chickenpox may

be contracted from a case of shingles but not vice versa.

Although thoracic dermatomes are most commonly involved ,

the

ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve is also frequently

affected; vesicles may appear on the cornea and lead to

ulceration. This condition can lead to blindness and urgent

ophthalmology review is required.

Geniculate ganglion

involvement causes the Ramsay Hunt syndrome of facial palsy

, ipsilateral loss of taste and buccal ulceration, plus a rash in

the external auditory canal

This may be mistaken for Bell’s palsy . Bowel and bladder dysfunction

occur with sacral nerve root involvement. The virus occasionally

causes cranial nerve palsy, myelitis or encephalitis. Granulomatous

cerebral angiitis is a cerebrovascular complication that leads to a

stroke-like syndrome in association with shingles, especially in an

ophthalmic distribution.

Post-herpetic neuralgia causes troublesome persistence of

pain for 1–6 months or longer, following healing of the rash. It

is more common in elderly.

Management Early therapy with aciclovir or related agents has

been shown to reduce both early- and late-onset pain, especially in

patients over 65 years. Post-herpetic neuralgia requires aggressive

analgesia, along with agents such as amitriptyline 25–100 mg

daily, gabapentin (commencing at 300 mg daily and building

slowly to 300 mg twice daily or more) or pregabalin

(commencing at 75 mg twice daily and building up to 100 mg

or 200 mg 3 times daily if tolerated). Capsaicin cream

(0.075%) may be helpful. Although controversial, glucocorticoids

have not been demonstrated to reduce post-herpetic neuralgia to

date.

Mumps

Mumps is a systemic viral infection characterised by swelling of the

parotid glands. Infection is endemic worldwide and peaks at 5–9 years

of age. Vaccination has reduced the incidence in children but

incomplete coverage and waning immunity with time have led to

outbreaks in young adults. Infection is spread by respiratory

Clinical features The median incubation period is 19 days, with a

range of 15–24 days. Classical tender parotid enlargement,

which is bilateral in 75%, follows a prodrome of pyrexia and

headache. Meningitis complicates up to 10% of cases.

Rare complications include encephalitis, transient hearing loss,

labyrinthitis, electrocardiographic abnormalities, pancreatitis and

arthritis. Approximately 25% of post-pubertal males with mumps

develop epididymo-orchitis but, although testicular atrophy occurs,

sterility is unlikely. The diagnosis is usually clinical. Treatment is

with analgesia.

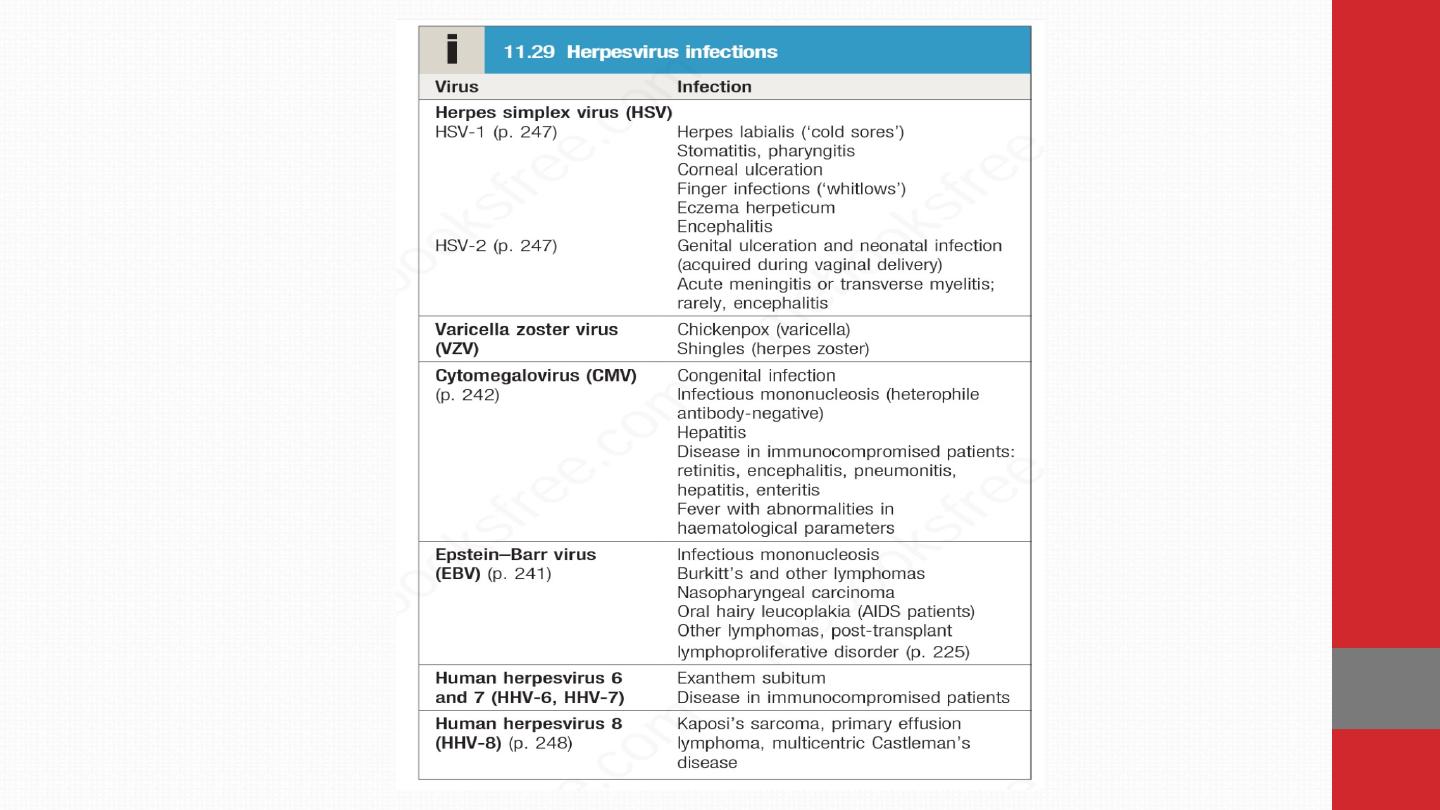

Infectious mononucleosis and

Epstein–Barr virus

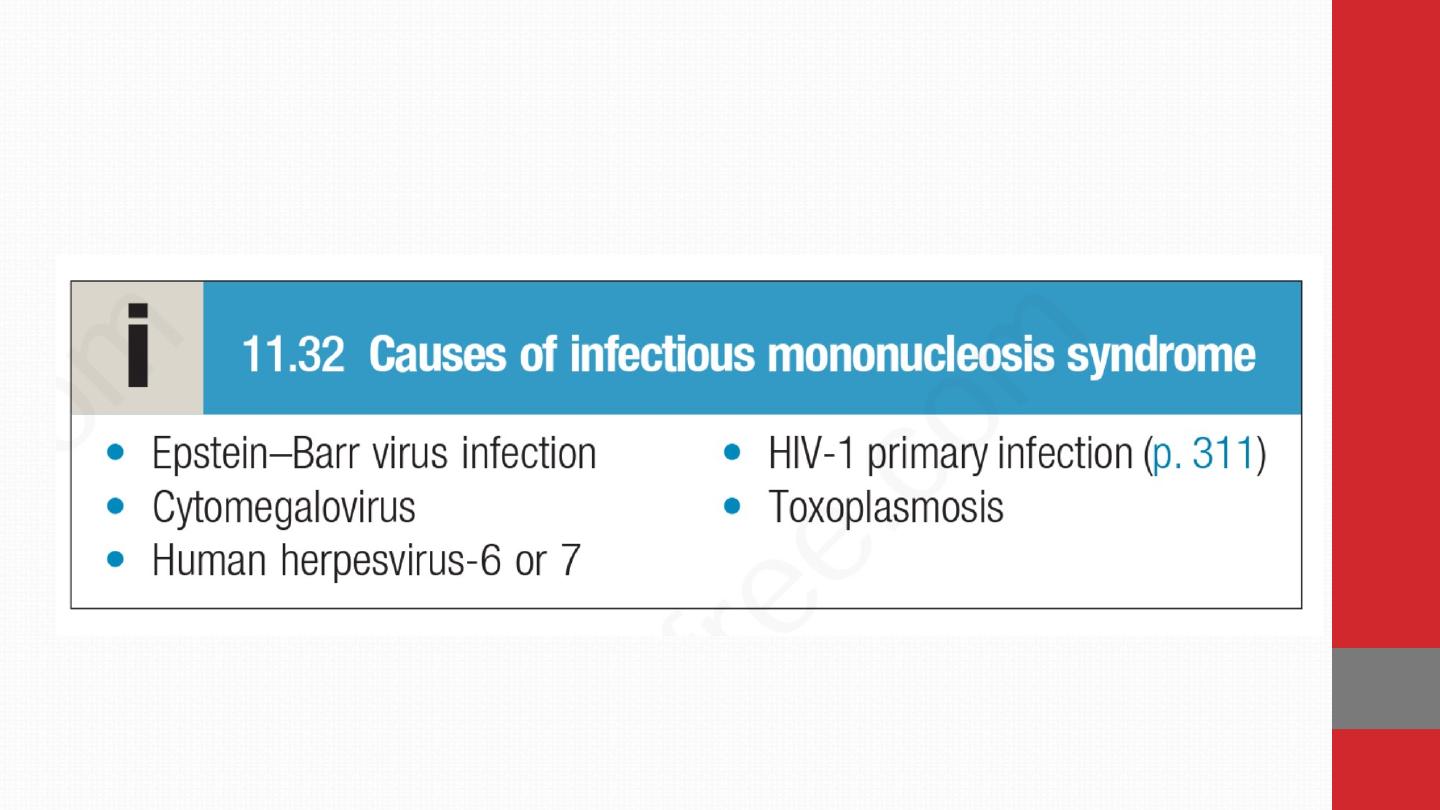

Infectious mononucleosis (IM) is a clinical syndrome

characterised by pharyngitis, cervical lymphadenopathy,

fever and lymphocytosis (known colloquially as glandular

fever). It is most often caused by Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) but

other infections can produce a similar clinical syndrome

EBV is a gamma herpesvirus. In developing countries, subclinical

infection in childhood is virtually universal. In developed

countries, primary infection may be delayed until adolescence or

early adult life. Under these circumstances, about 50% of

infections result in typical IM. The virus is usually acquired from

asymptomatic excreters via saliva, either by droplet infection or

environmental contamination in childhood, or by kissing among

adolescents and adults. EBV is not highly contagious and

isolation of cases is unnecessary.

Clinical features EBV infection has a prolonged but

undetermined incubation period, followed in some cases by a

prodrome of fever, headache and malaise. This is followed by

IM with severe pharyngitis, which may include tonsillar

exudates and non-tender anterior and posterior cervical

lymphadenopathy. Palatal petechiae, periorbital oedema,

splenomegaly, inguinal or axillary lymphadenopathy, and

macular, petechial or erythema multiforme rashes may

occur. In most cases, fever resolves over 2 weeks, and fatigue

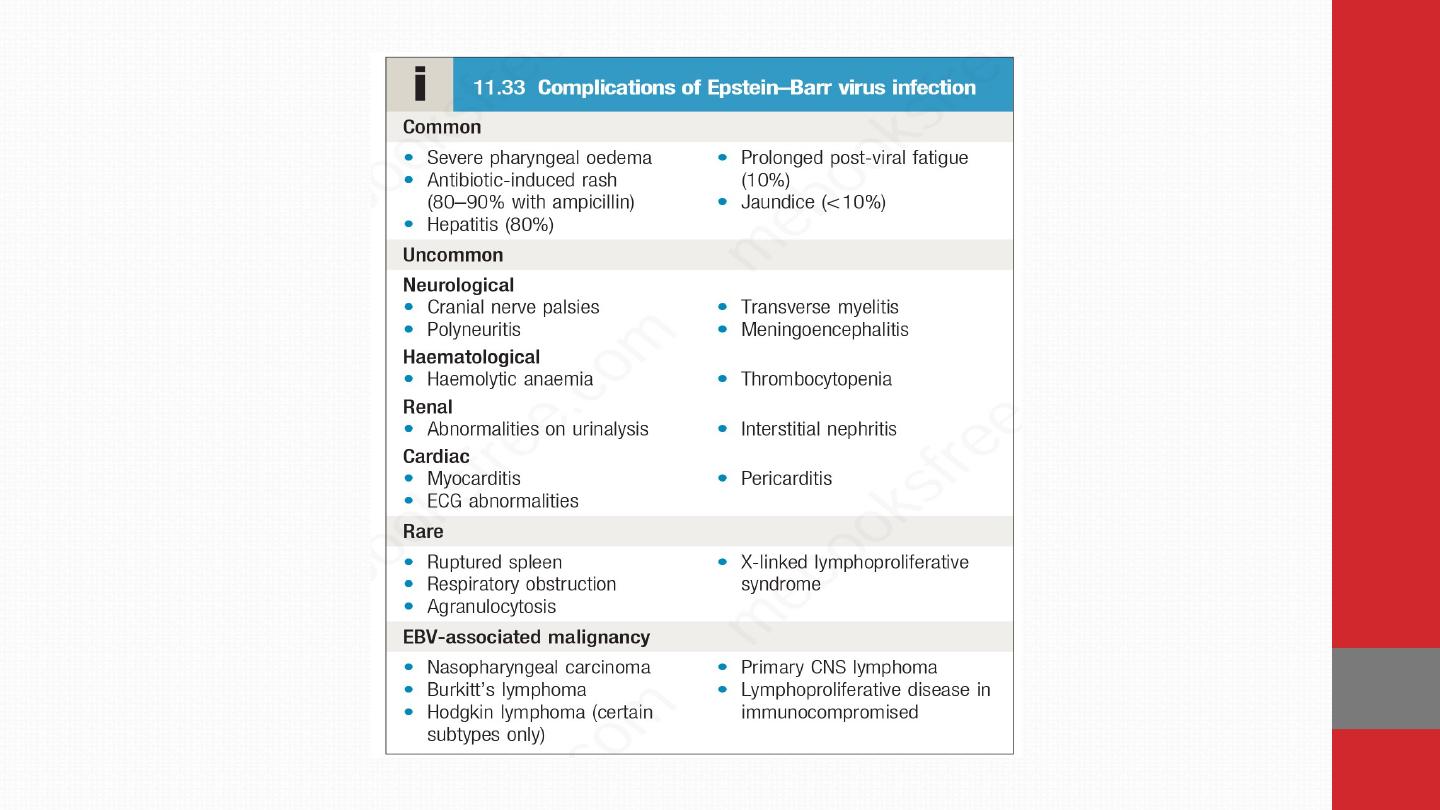

and other abnormalities settle over a further few weeks. Death

is rare but can occur due to respiratory obstruction,

haemorrhage from splenic rupture, thrombocytopenia or

encephalitis.

The diagnosis of EBV infection outside the usual age in

adolescence and young adulthood is more challenging. In

children under 10 years the illness is mild and short-lived, but

in adults over 30 years of age it can be severe and prolonged.

In both groups, pharyngeal symptoms are often absent. EBV may

present with jaundice, as a PUO or with a complication.

Long-term complications of EBV infection Lymphoma complicates

EBV infection in immunocompromised hosts, and some forms of

Hodgkin lymphoma are EBV-associated . The endemic form of

Burkitt’s lymphoma complicates EBV infection in areas of sub-

Saharan Africa where falciparum malaria is endemic.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is a geographically restricted

tumour seen in China and Alaska that is associated with EBV

infection.

Investigations

Atypical lymphocytes are common in EBV

infection

but also occur in other causes of IM, acute retroviral

syndrome with HIV infection, viral hepatitis, mumps and rubella. They

are also a feature of dengue, malaria and other geographically

restricted infections. A ‘heterophile’ antibody is present during

the acute illness and convalescence, which is detected by the

Paul–Bunnell or ‘Monospot’ test.

Specific EBV serology confirms the diagnosis. Acute infection is

characterised by IgM antibodies against the viral capsid, antibodies to

EBV early antigen and the initial absence of antibodies to EBV nuclear

antigen (anti-EBNA). Seroconversion of anti-EBNA at approximately 1

month after the initial illness may confirm the diagnosis in retrospect.

CNS infections may be diagnosed by detection of viral DNA in CSF.

Management

Treatment is largely symptomatic.

If a throat

culture yields a β-haemolytic streptococcus, penicillin should be

given.

Administration of ampicillin or amoxicillin in this

condition commonly causes an itchy macular rash and should

be avoided.

When pharyngeal oedema is severe, a short

course of glucocorticoids, e.g. prednisolone 30 mg daily for 5

days, may help. Current antiviral drugs are not active against

EBV.Return to work or school is governed by physical fitness rather

than laboratory tests;

contact sports should be avoided until

splenomegaly has resolved because of the danger of splenic

rupture

.