Staphylococcal Infections

DONE BY

DR MARWAN MAJEED IBRAHIM

CABM INTERNAL MEDICINE FICM PULMONARY MEDICINE

Staphylococcus aureus, the most virulent of the many

staphylococcal species. S. aureus is a pluripotent pathogen, causing

disease through both toxin- and non-toxin-mediated mechanisms. It

is responsible for numerous nosocomial and community- based

infections that range from relatively minor skin and soft tissue

infections (SSTIs) to life-threatening systemic infections. The “other”

staphylococci,

collectively

designated

coagulase-

negative

staphylococci (CoNS), are considerably less virulent than S. aureus

but remain important pathogens in select settings, such as

infections that involve prosthetic devices.

•

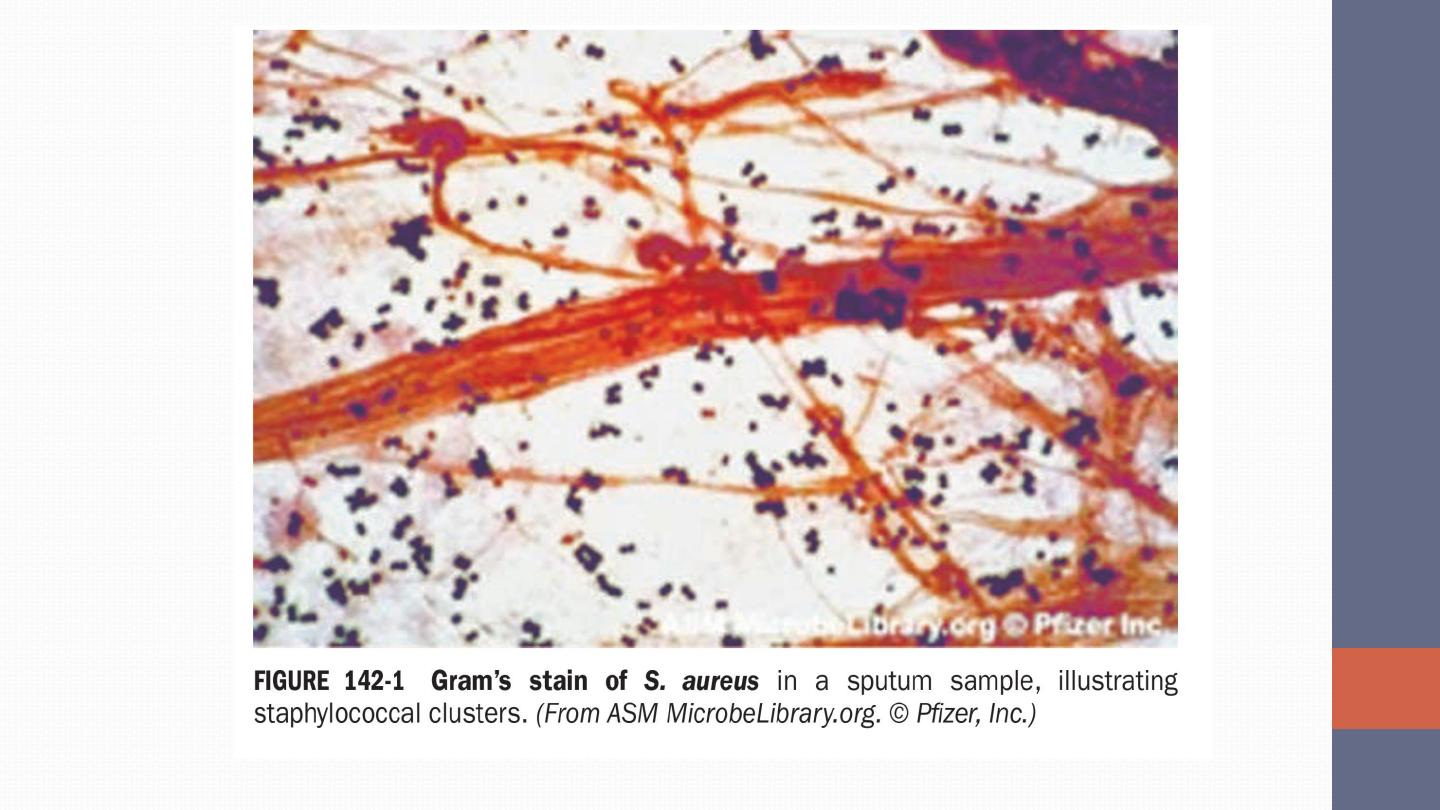

Staphylococci, gram-positive cocci, form grapelike clusters on

Gram’s stain . These organisms (~1 μm in diameter) are catalase-

positive (unlike streptococcal species), non-motile, aerobic, and

facultatively anaerobic.

They are capable of prolonged survival on

environmental surfaces under varying conditions

.

•

With few exceptions, S. aureus is distinguished from other

staphylococcal species by its production of

coagulase +ve

, a

surface enzyme that converts fibrinogen to fibrin.

S. AUREUS INFECTIONS

S. aureus is both a commensal and an opportunistic pathogen.

Approximately 20–40% of healthy persons are colonized with S.

aureus, with a smaller percentage (~10%) persistently colonized with

the same strain.

The rate of colonization is elevated among insulin-

dependent diabetics, HIV-infected patients, patients undergoing

hemodialysis, injection drug users, and individuals with skin

damage.

The anterior nares and oropharynx are frequent sites of

human colonization, although the skin (especially when damaged),

vagina, axilla, and perineum are also often colonized

. These

colonization sites serve as potential reservoirs for future infections.

•

In the past three decades, there has been a dramatic change in the

epidemiology of infections due to

methicillin-resistant S. aureus

(MRSA). In addition to its major role as a nosocomial pathogen,

MRSA has become an established community-based pathogen.

•

The S. aureus toxin

Panton-Valentine leukocidin

is cytolytic to

PMNs, macrophages, and monocytes. Strains elaborating this

toxin have been epidemiologically linked with cutaneous and more

serious infections caused by strains of CA-MRSA.

•

S. aureus produces three types of toxin: cytotoxins, pyrogenic

toxin superantigens, and exfoliative toxins.

DIAGNOSIS

•

Elevated ESR, CRP & leukocytosis (band formation).

•

Peptide nucleic acid fluorescence in situ hybridization (PAN FISH) +ve.

•

Staphylococcal infections are readily diagnosed by Gram’s stain and

microscopic examination of abscess contents or of infected tissue.

Routine culture of infected material usually yields positive results,

and blood cultures are sometimes positive even when infections are

localized to extravascular sites. S. aureus is rarely a blood culture

contaminant.

•

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based assays are now often used for

the rapid diagnosis of S. aureus infection. A number of point-of-care

tests are now available to screen patients for colonization with

MRSA.

CLINICAL SYNDROMES

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

•

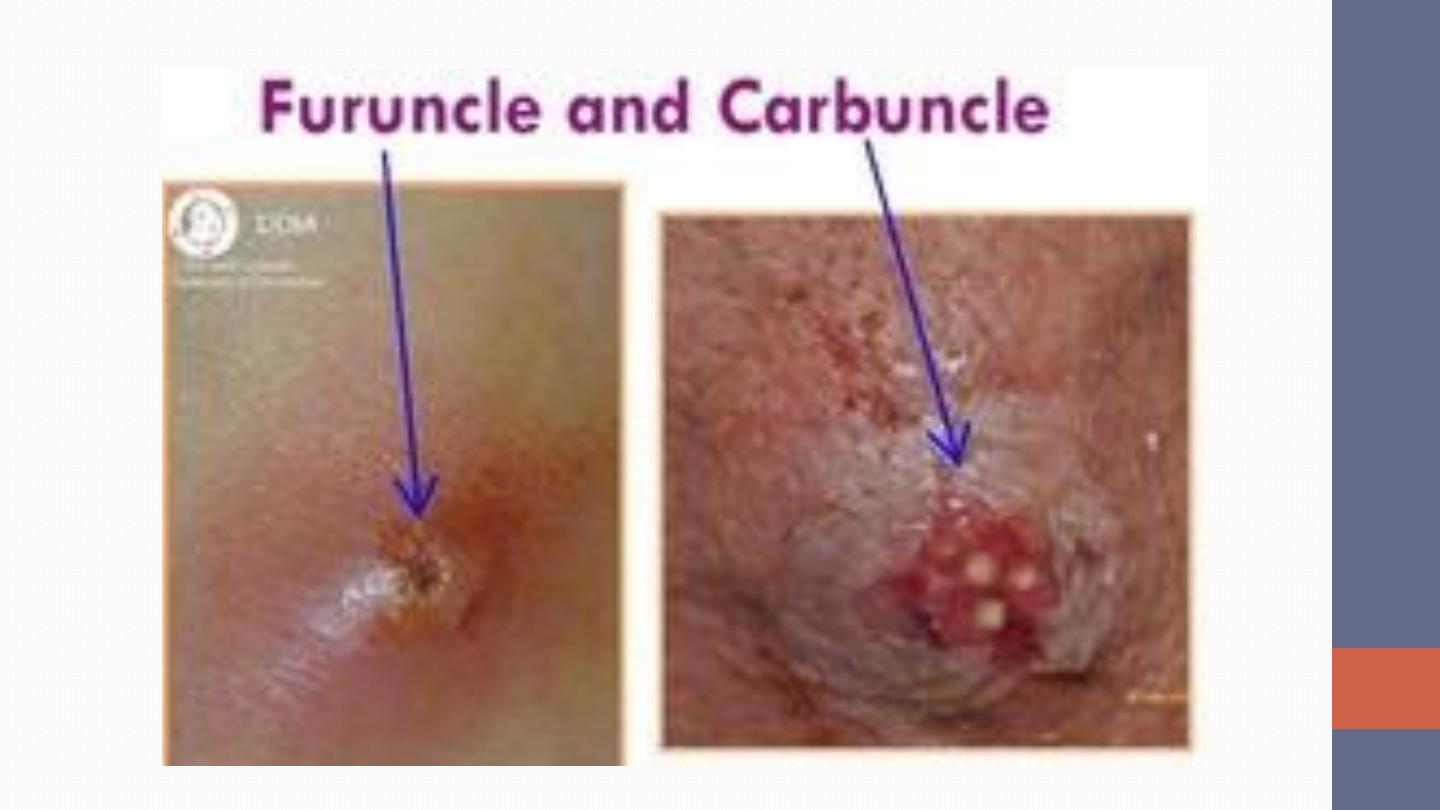

Folliculitis is a superficial infection that involves the hair follicle,

with a central area of purulence (pus) surrounded by induration

and erythema.

•

Furuncles (boils) are more extensive, painful lesions that tend to

occur in hairy, moist regions of the body and extend from the

hair follicle to become a true abscess with an area of central

purulence.

•

Carbuncles are most often located in the lower neck and are even

more severe and painful, resulting from the coalescence of other

lesions that extend to a deeper layer of the subcutaneous tissue.

SEPTIC EMBOLI

CELLULITIS

Musculoskeletal Infections

Hematogenous osteomyelitis in children most often involves the

long bones. Infections present with fever and bone pain or with

a child’s reluctance to bear weight. The white blood cell count and

erythrocyte sedimentation rate are often elevated. Blood

cultures are positive in ~50% of cases.

vertebral osteomyelitis & Discitis

is among the more common

clinical presentations. Often seen in patients with endocarditis,

those undergoing hemodialysis, diabetics, and injection drug

users. These infections may present as intense back pain with fever

but may also be clinically occult, presenting as chronic back pain

with low-grade fever. S. aureus is the most common cause of

epidural abscess, a complication that can result in neurologic

compromise. Patients report difficulty voiding or walking and

radicular pain in addition to the symptoms associated with their

osteomyelitis. Surgical intervention in this setting often constitutes

a medical emergency. MRI is USED to establish the diagnosis.

In both children and adults,

S. aureus is the most common cause

of septic arthritis in native joints

. This infection is rapidly

progressive and may be associated with extensive joint destruction

if left untreated.

It presents with intense pain on motion of the

affected joint, swelling, and fever

.

Aspiration of the joint

reveals turbid fluid, with >50,000 PMNs/ μL and gram-positive

cocci in clusters on Gram’s stain

In adults, septic arthritis may result from trauma, surgery, or

hematogenous dissemination

. The most commonly involved joints

include the knees, shoulders, hips, and phalanges. Infection

frequently develops in joints previously damaged by osteoarthritis

or rheumatoid arthritis. Iatrogenic infections resulting from

aspiration or injection of agents into the joint also occur.

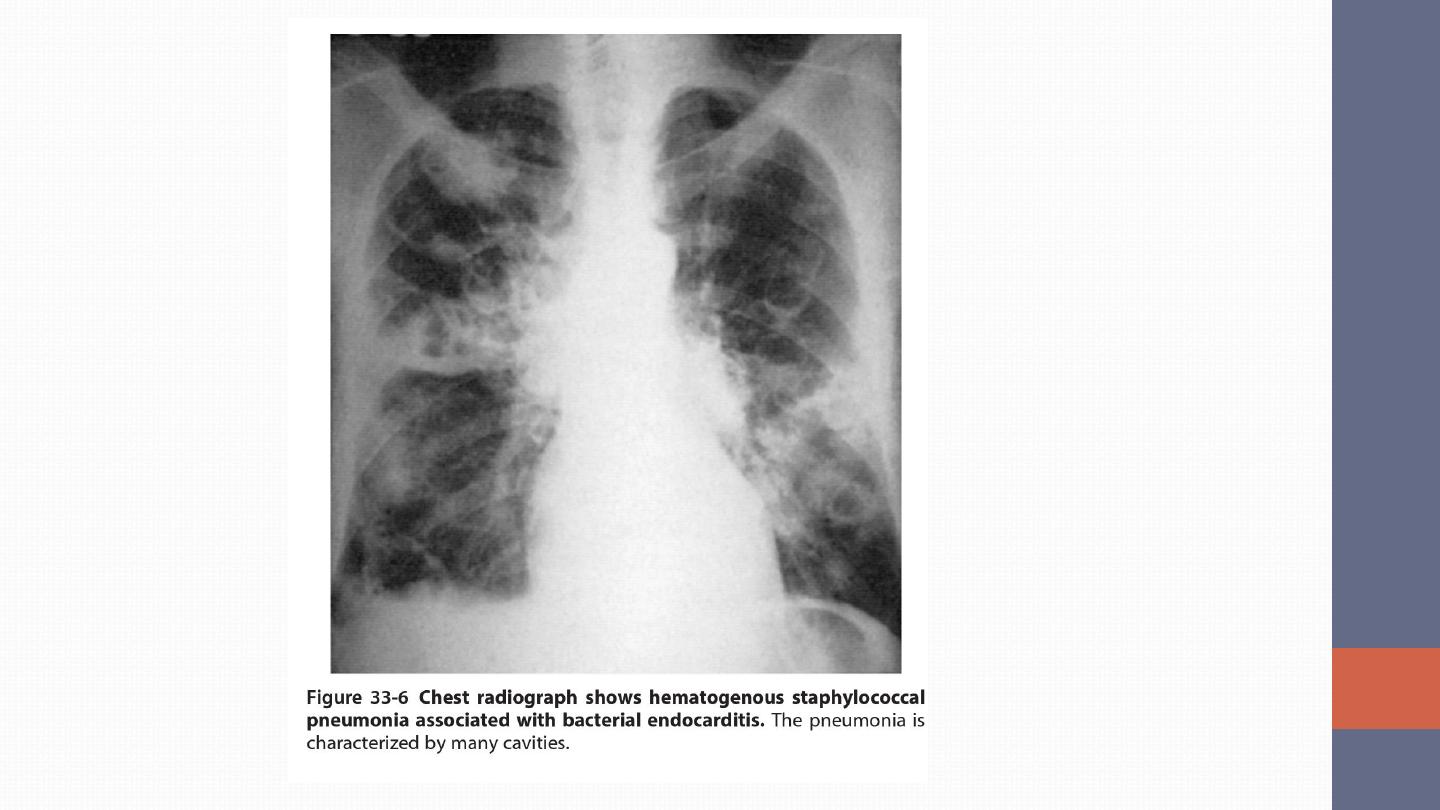

Respiratory Tract Infections

•

In adults, nosocomial S. aureus pulmonary infections are common

among intubated patients in intensive care units. Nasally colonized

patients are at increased risk of these infections. Chest x-ray may

reveal pneumatoceles (shaggy, thin-walled cavities). Pneumothorax

and empyema are recognized complications.

•

Community-acquired respiratory tract infections due to S. aureus

often follow viral infections—most commonly influenza. Patients may

present with fever, bloody sputum production, and midlung-field

pneumatoceles or multiple, patchy pulmonary infiltrates. Diagnosis is

made by sputum Gram’s stain and culture. Blood cultures, although

useful, are usually negative

.

Bacteremia, Sepsis, and Infective Endocarditis S. aureus

bacteremia may be complicated by sepsis, endocarditis, vasculitis,

or metastatic seeding (establishment of suppurative collections at

other tissue sites). Among the more commonly seeded tissue sites

are bones, joints, kidneys, and lungs.

•

Acute right-sided tricuspid valvular S. aureus endocarditis is

most often seen in injection drug users

•

S. aureus is one of the more common causes of prosthetic-valve

endocarditis. This infection is especially fulminant in the early

postoperative period and is associated with a high mortality rate

Other infections:

•

Prosthetic Device–Related Infections

•

Urinary Tract Infections

•

Toxin-Mediated Diseases ; FOOD POISONING Even if the bacteria

are killed by warming, the heat-stable toxin is not destroyed. The

onset of illness is rapid, occurring within 1–6 h of ingestion. The

illness is characterized by nausea and vomiting, although diarrhea,

hypotension, and dehydration also may occur

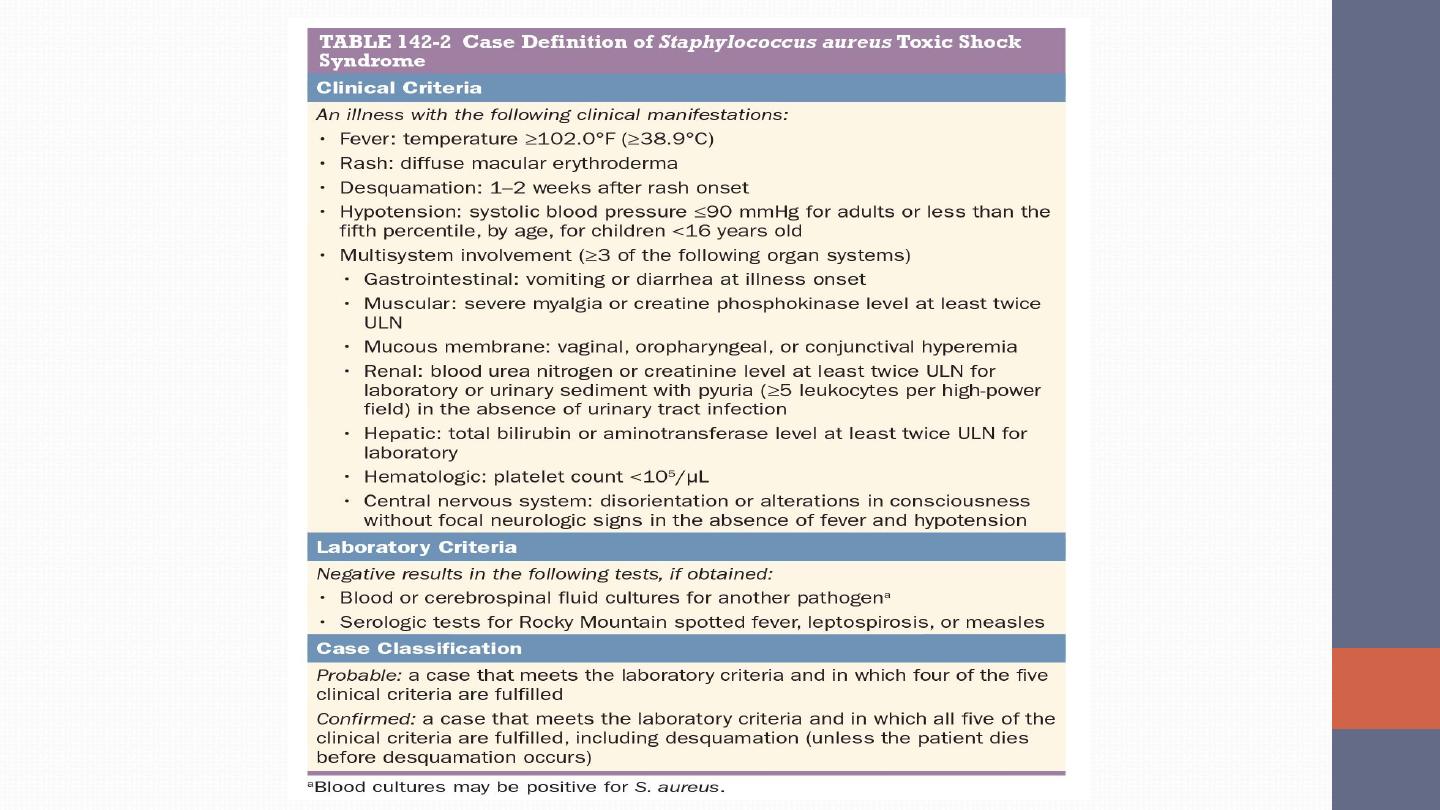

TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME The clinical presentation is similar in

menstrual and nonmenstrual TSS. Evidence of clinical S. aureus

infection is not a necessary . TSS results from the elaboration of an

enterotoxin or the structurally related enterotoxin-like TSST-1

COAGULASE-NEGATIVE

STAPHYLOCOCCAL INFECTIONS

S. epidermidis is the CoNS species most often associated with

prosthetic device infections

. Infection is a two-step process, with

initial adhesion to the device followed by colonization. S.

epidermidis is uniquely adapted to colonize these devices because

of its capacity to elaborate the extracellular polysaccharide

(glycocalyx or slime) that facilitates formation of a protective biofilm

on the device surface.

CLINICAL SYNDROMES CoNS cause a diverse array of prosthetic

device–related infections, including those that involve prosthetic

cardiac valves and joints, vascular grafts, intravascular devices,

and CNS shunts. In all of these settings, the clinical presentation is

similar. The signs of localized infection are often subtle, the rate of

disease progression is slow, and clinical presentation is slow.

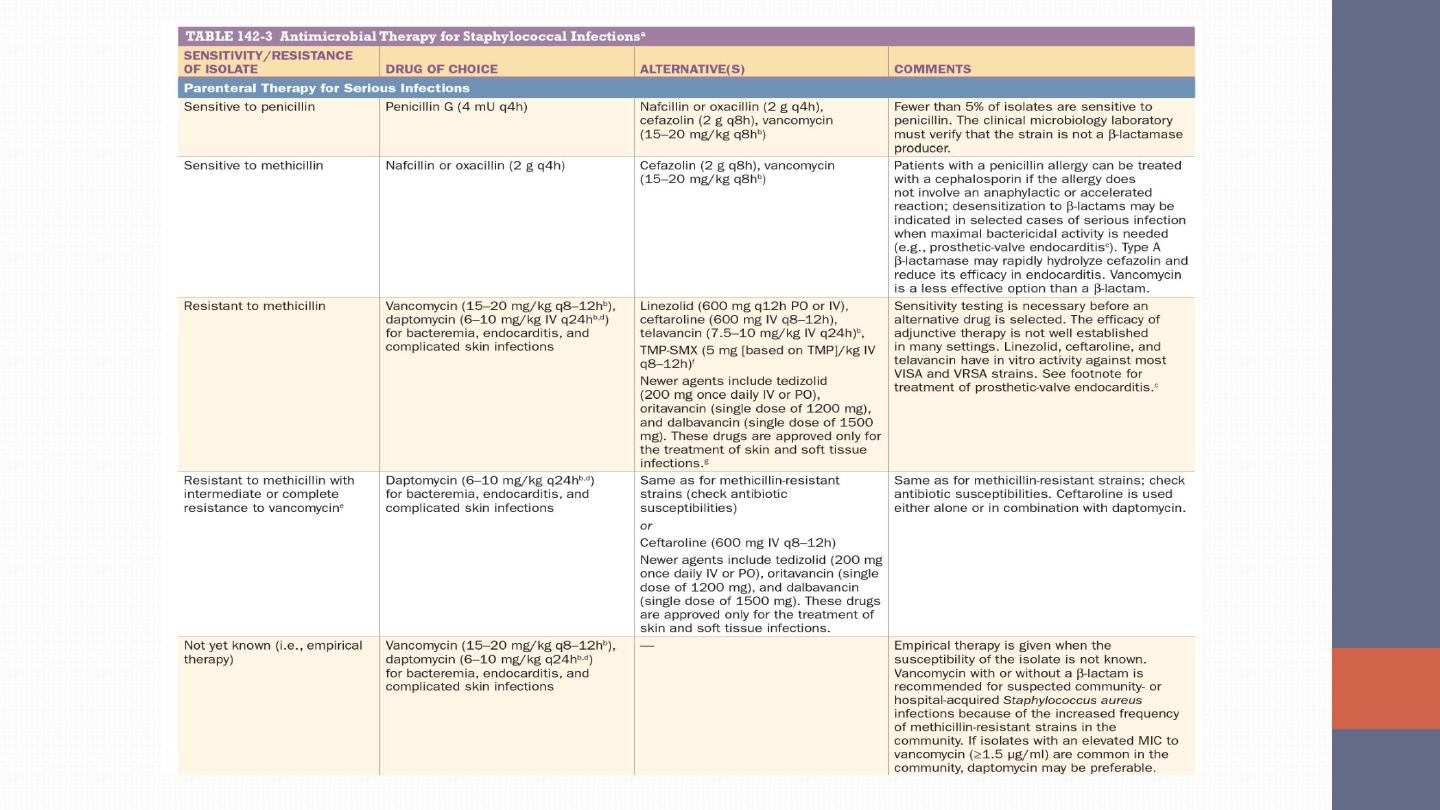

TREATMENT

•

Source control (e.g.,), coupled with rapid institution of appropriate

antimicrobial therapy.

•

Few strains of staphylococci (≤5%) remain susceptible to penicillin.

•

Penicillin-resistant isolates are treated with semisynthetic penicillinase-

resistant penicillins (SPRPs), such as oxacillin or nafcillin.

•

The isolation of MRSA was reported within 1 year of the introduction

of methicillin. Since then, the prevalence of MRSA has steadily

increased

•

Vancomycin or daptomycin is recommended as the drug of choice for

the treatment of invasive MRSA infections.

•

In 2002, the first clinical isolate of fully vancomycin-resistant S.

aureus (VRSA) was reported treated with daptomycin or

Linezolid—the first oxazolidinone—is bacteriostatic against

staphylococci; it offers the advantage of comparable bioavailability

after oral or parenteral administration.

•

Ceftaroline is a fifth-generation cephalosporin with bactericidal

activity against MRSA (including strains with reduced

susceptibility to vancomycin and daptomycin).

Combinations of antistaphylococcal agents have been used to

enhance bactericidal activity in the treatment of deep-seated

infections, to shorten the duration of therapy (e.g., for right-sided

endocarditis), or to optimize empirical therapy when the

susceptibility of the isolate to methicillin is not yet known (e.g.,

using a β-lactam plus vancomycin). Among the additional

antimicrobial agents often used are rifampin, gentamicin, fusidic

acid, doxycycline and clindamycin.