1

THI QAR U. MEDICAL COLLEGE LECTURES 2017

DEPARTMENT OF INTERNAL MEDICINE Dr. FAEZ KHALAF, SUBSPACIALITY GIT

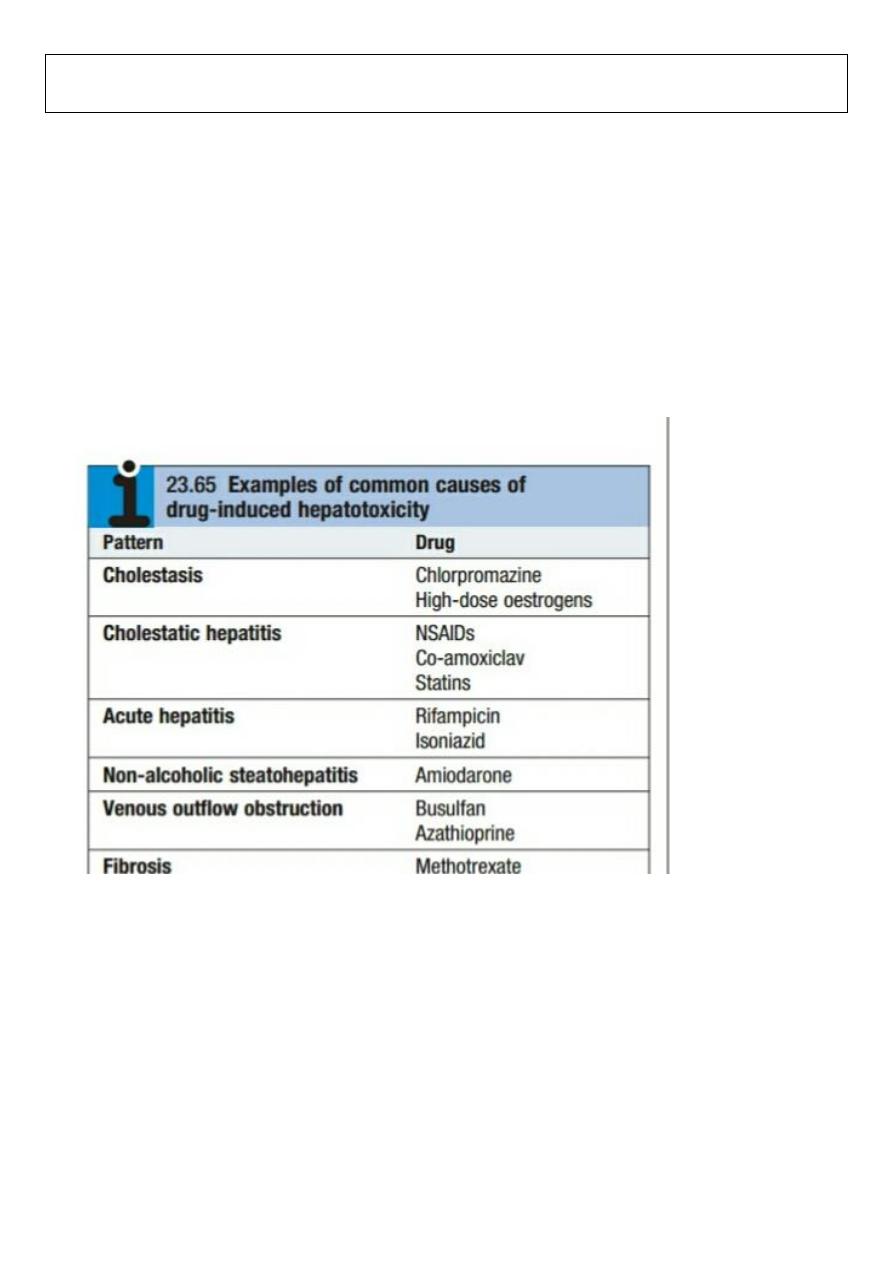

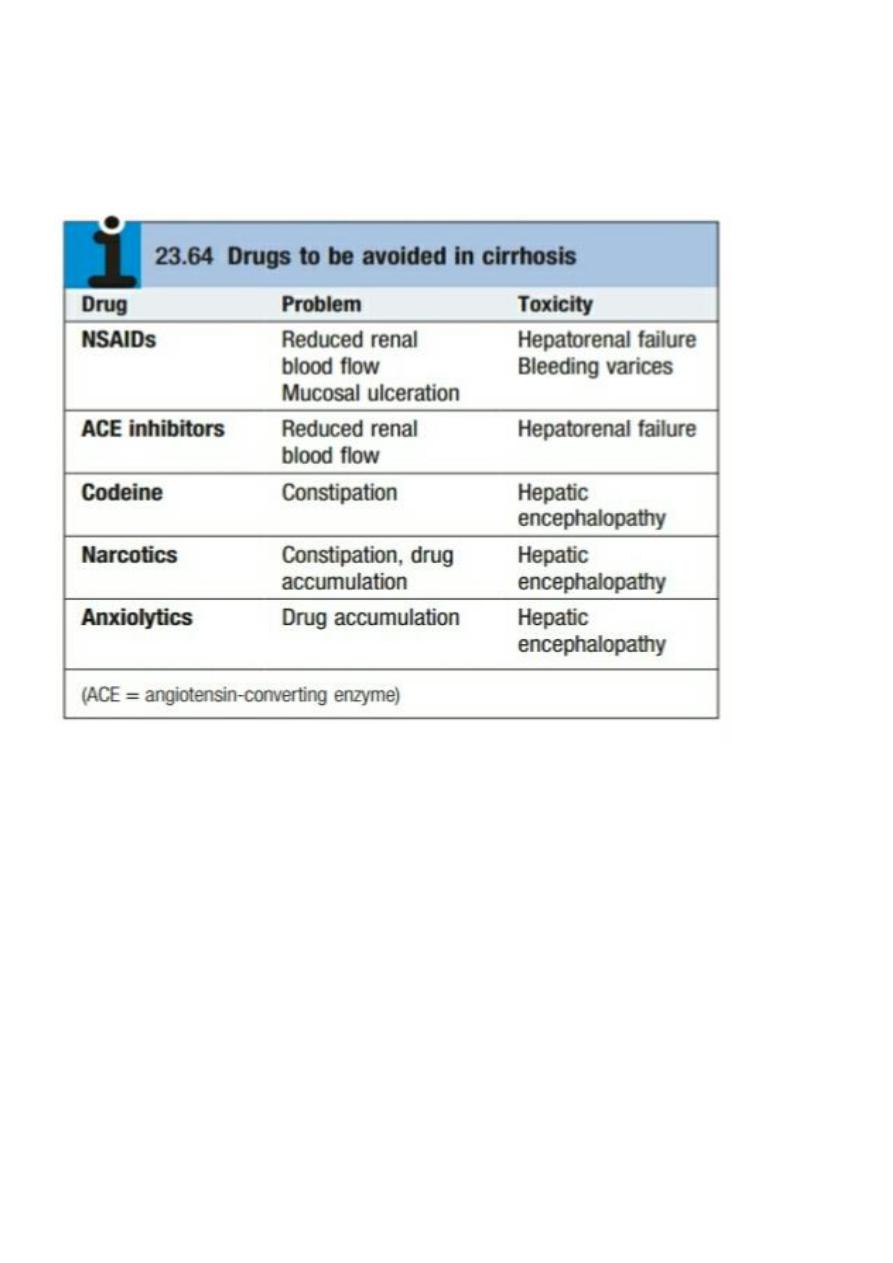

Drug & Toxin-Induced Hepatic Disease

• Mechanism of injury:

1.

Direct toxicity (Drugs are often divided into dose-dependent, or predictable, hematotoxins and dose-

independent, or unpredictable (idiosyncratic), hematotoxins)

2.

Hepatic conversion of a xenobiotic to an actual toxin

3.

Immune mechanisms

drug or metabolite acts as hapten

• Types of injury:

1.

Hepatocyte necrosis

2.

Cholestasis

3.

Insidious liver dysfunction

• Reye syndrome – children given ASA; extensive accumulation of fat droplets within hepatocytes

(micro vesicular steatosis)

Reye syndrome

•

Usually in children

< 4 years

of age

.

•

Often follows a chickenpox or influenza infection

•

Mitochondrial damage ( virus, salicylates)

1. Disruption of urea cycle increased serum ammonia

2. Defective beta-oxidation of fatty acids

•

Micro vesicular steatosis (Salicylate effect)

•

Clinical findings:

2

1. Encephalopathy

2. Hepatomegaly liver failure

•

Laboratory findings:

1. Transaminasemia

2. Normal to slight inc. total bilirubin

3. Increased serum ammonia

ACETAMINOPHEN

•

Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is a widely used analgesic available without prescription. It is safe when taken

in the recommended therapeutic dose of

1 to 4 g daily

, but hepatotoxicity produced by self-poisoning with

acetaminophen has been recognized since the 1960s. Despite the effectiveness of thiol-based antidotes,

acetaminophen remains the most common cause of drug-induced liver injury in most countries and an important

cause of acute liver failure. Para suicide and suicide are the usual reasons for overdose.

•

Single doses of acetaminophen that exceed

7 to 10 g (140 mg/kg body weight in children)

may cause liver

injury, but this outcome is not inevitable. Severe liver injury

(serum ALT level greater than 1000 U/L)

or fatal cases

usually involve doses of at least

15 to 25 g,

•

Among heavy drinkers and chronic liver diseases, daily acetaminophen doses of

2 to 6 g

have been

associated with fatal hepatotoxicity.

3

•

Self-poisoning with acetaminophen is most common in young women, but fatalities are most frequent in

men, possibly because of alcoholism and late presentation.

•

In the first two days after acetaminophen self-poisoning, features of liver injury are not present. Nausea,

vomiting, and drowsiness are often caused by concomitant ingestion of alcohol and other drugs.

After 48 to 72

hours,

serum ALT levels may be elevated, and symptoms such as anorexia, nausea and vomiting, fatigue, and malaise

may occur. Hepatic pain may be pronounced. In severe cases, the course is characterized by repeated vomiting,

jaundice, hypoglycemia, and other features of acute liver failure, particularly coagulopathy and hepatic

encephalopathy.

•

Indicators of a poor outcome include grade IV hepatic coma, acidosis, severe and sustained impairment of

coagulation factor synthesis, renal failure, and a pattern of falling serum ALT levels in conjunction with a worsening

prothrombin time.

Management:

•

In patients who present within

four hours

of ingesting an excessive amount of acetaminophen, the stomach

should be emptied with a wide-bore gastric tube. Osmotic cathartics or binding agents have little if any role in

management. Charcoal hemoperfusion has no established role. The focus of management is on identifying patients

who should receive thiol-based antidote therapy and, in those with established severe liver injury, assessing the

patient's candidacy for liver transplantation.

•

Cases of acetaminophen-induced severe liver injury are virtually abolished if N acetyl cysteine ( NAC ) is

administered within

12 hours

and possibly within

16 hours of

acetaminophen ingestion. After

16 hours,

thiol

donation is unlikely to affect the development of liver injury because oxidation of acetaminophen to NAPQI with

consequent oxidation of thiol groups is complete and mitochondrial injury and activation of cell death pathways are

likely to be established.

NAC DOSE AND ADMINISTERATION :

•

Oral administration is preferred in the United States,with a loading dose of

140 mg/kg

followed by

administration of 70 mg/kg every 4 hours for 72 hours.

This regimen is highly effective, despite the theoretical

disadvantage that delayed gastric emptying and vomiting may reduce intestinal absorption of NAC. In Europe and

Australia, NAC is administered by slow bolus intravenous injection followed by infusion

(150 mg/kg over 15 minutes

in

200 mL of 5%

dextrose, with a second dose of

50 mg/kg 4 hours later,

if the blood acetaminophen levels indicate a

high risk of hepatoxicity, and

a total dose over 24 hours of 300 mg/kg

).The intravenous route may be associated with

a higher rate of hypersensitivity reactions because of the higher systemic blood levels achieved.

4

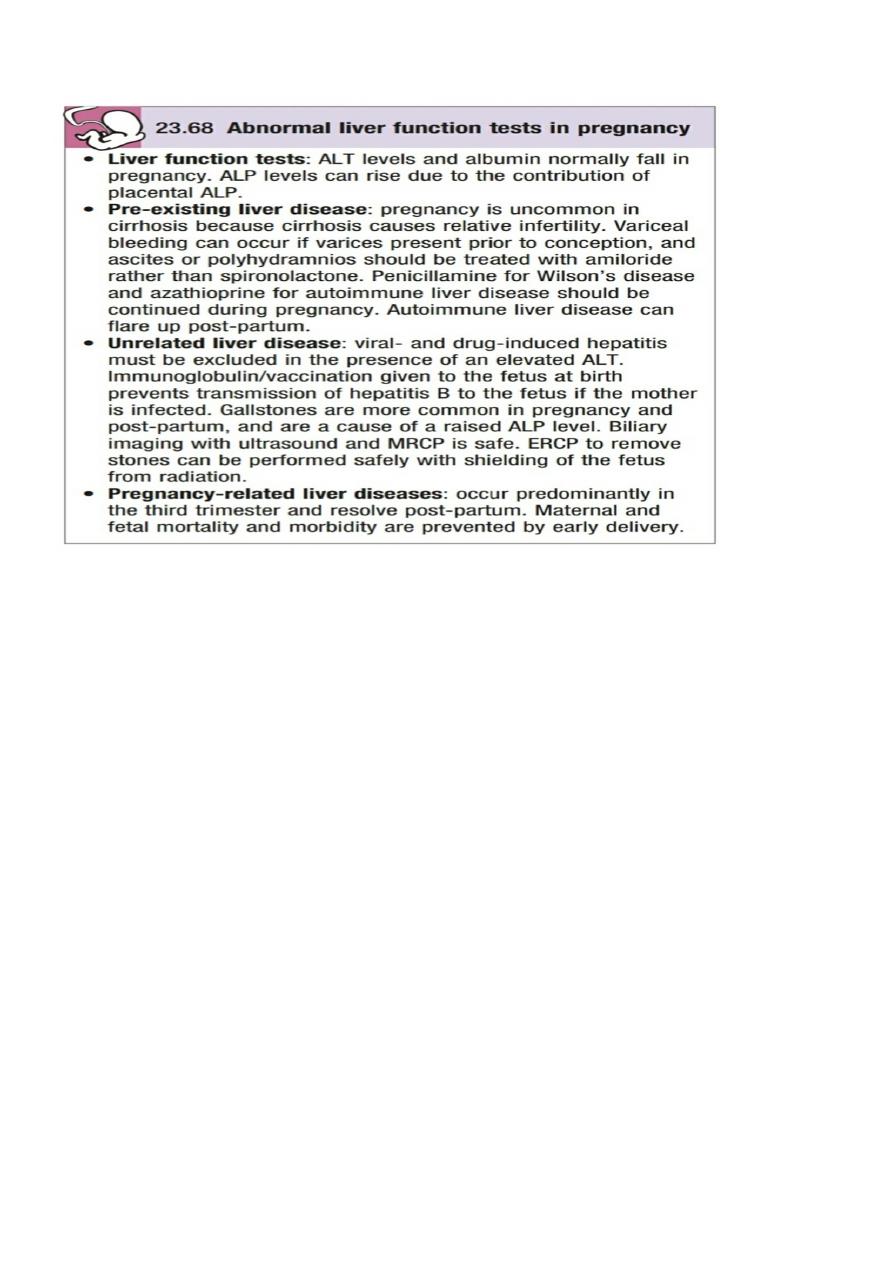

Hepatic Disease Associated with Pregnancy

Pre-eclampsia

•

Hypertension, proteinuria, dependent pitting edema in the third trimester

•

HELLP

syndrome

hemolytic anemia with schistocytes, elevated liver enzymes, low

platelet (due to DIC)

•

Morphology:

fibrin deposition in periportal sinusoids

hemorrhage into space of Disse

periportal hepatocellular coagulative necrosis

The HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets) is a variant of pre-eclampsia

that tends to affect multiparous women. It usually

presents at

27–36

weeks of pregnancy with hypertension,

proteinuria and fluid retention.

Jaundice only occurs in

5%

of cases. Blood tests may show low hemoglobin, with fragmented red cells,

markedly elevated serum transaminases and raised D-dimers.

The condition can be complicated by hepatic infarction and rupture.

Maternal complications also include disseminated intravascular coagulation and placental abruption.

Maternal mortality is

1%

and perinatal mortality can be up to

30%.

Delivery usually leads to prompt resolution,

and disease recurs in fewer than

5%

of subsequent pregnancies.

5

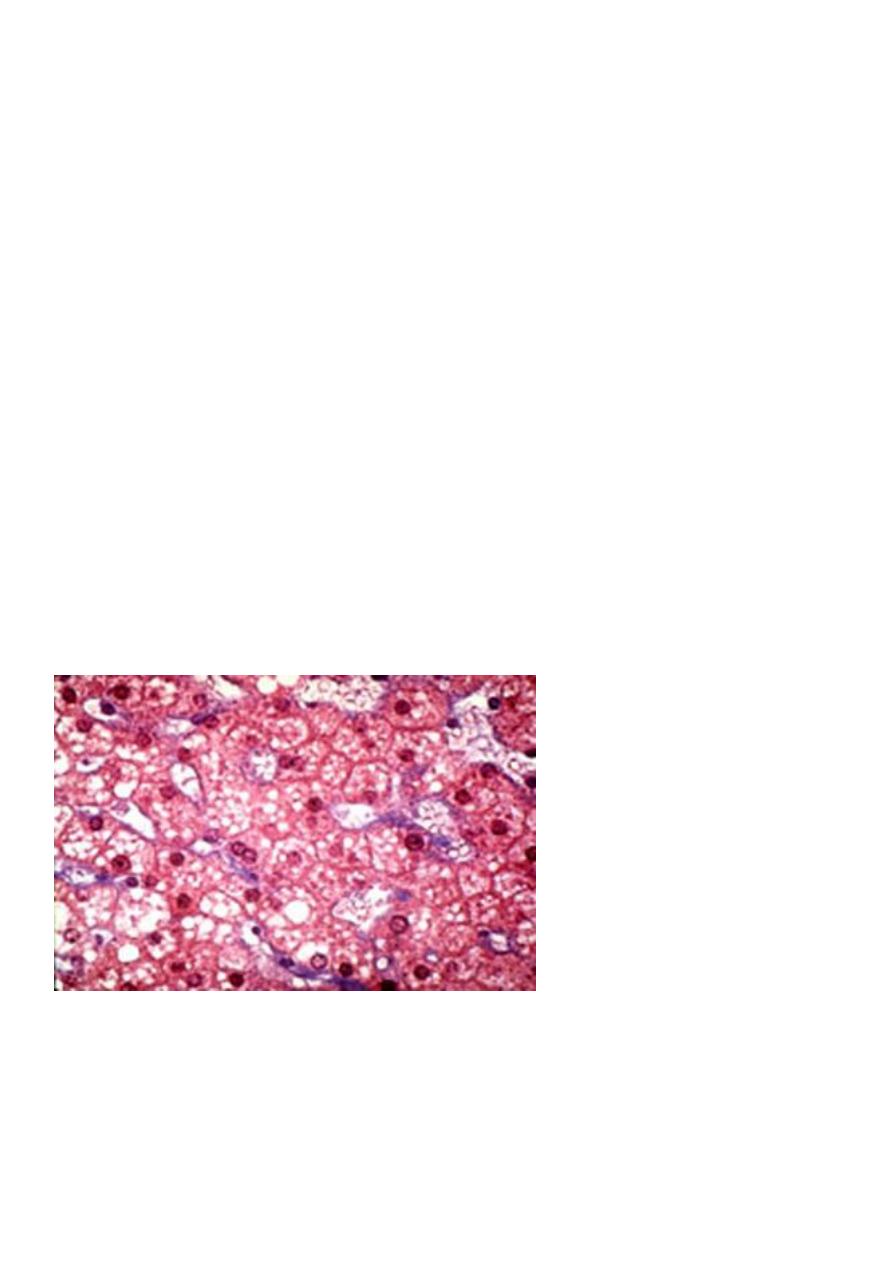

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP)

•

sub-clinical hepatic dysfunction to hepatic failure, coma and death

•

Abnormality in beta-oxidation of fatty acids

•

3

rd

trimester; with multiple metabolic defects

•

diagnosis depends on:

a) high index of suspicion

b) characteristic micro vesicular steatosis demonstrated on frozen tissue

sections OR with stain (

oil red-O or Sudan black

)

•

Treatment: termination of pregnancy

This is more common in twin and first pregnancies, and may arise more frequently when the fetus is male .

It occurs in 1 in 14 000 pregnancies in the USA

.

It typically presents between 31 and 38 weeks of pregnancy

with vomiting and abdominal pain followed by jaundice. In severe cases, this may be followed by lactic acidosis,

coagulopathy, encephalopathy and renal

failure. Hypoglycaemia can also occur .

. Differentiation from toxaemia of pregnancy (which is more common) can be achieved by the finding of high serum

uric acid levels and the absence of haemolysis. Overlap between acute fatty liver of pregnancy, HELLP and toxaemia

of pregnancy can occur.

Early diagnosis, specialist care and delivery of the fetus have led to a fall in maternal and perinatal mortality to

1%

and

7%

respectively

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: lobular parenchyma characterized by microvesicular steatosis and a small number of

lymphocytes. (H&E)

6

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

•

Characteristics:

a) onset of pruritus in

3

rd

trimester

b) darkening of urine with occ. light stools

c) jaundice – conjugated hyperbilirubinemia

•

Mechanism: altered hormonal state + biliary secretion defects

cholestasis

•

Increased incidence of fetal distress, stillbirth and prematurity

This accounts for

20%

of cases of jaundice in pregnancy

;

it usually occurs in the third trimester of pregnancy but can arise earlier. It may be linked with intrauterine growth

retardation and premature birth, but is most characteristically associated with intrauterine fetal death if the

pregnancy goes beyond

36 weeks

of gestation.

The condition characteristically presents with itching an cholestatic LFTs

.

Bile salts are elevated in the serum and this represents a useful clinical test. Delivery leads to resolution and should

be considered

from

36 weeks

onwards

Pregnancy should not be allowed to continue beyond term because of a steep rise in the risk of intrauterine death.

UDCA

(15 mg/kg daily)

effectively controls itching and probably prevents premature birth.

The major issue with UDCA in acute

cholestasis of pregnancy is the relatively long time required to achieve effective levels within the bile pool,

Cholestasis recurs in

60%

of future pregnancies.

Nodules & Tumors

Nodular Hyperplasia

•

non-cirrhotic liver nodules

•

types:

Focal nodular hyperplasia

spontaneous mass lesion; female preponderance

Morphology:

a) central stellate scar with large arterial vessels

exhibiting fibromuscular hyperplasia (+) narrowed

lumen

b) Intense alymphocytic infiltration

c) bile duct proliferation

7

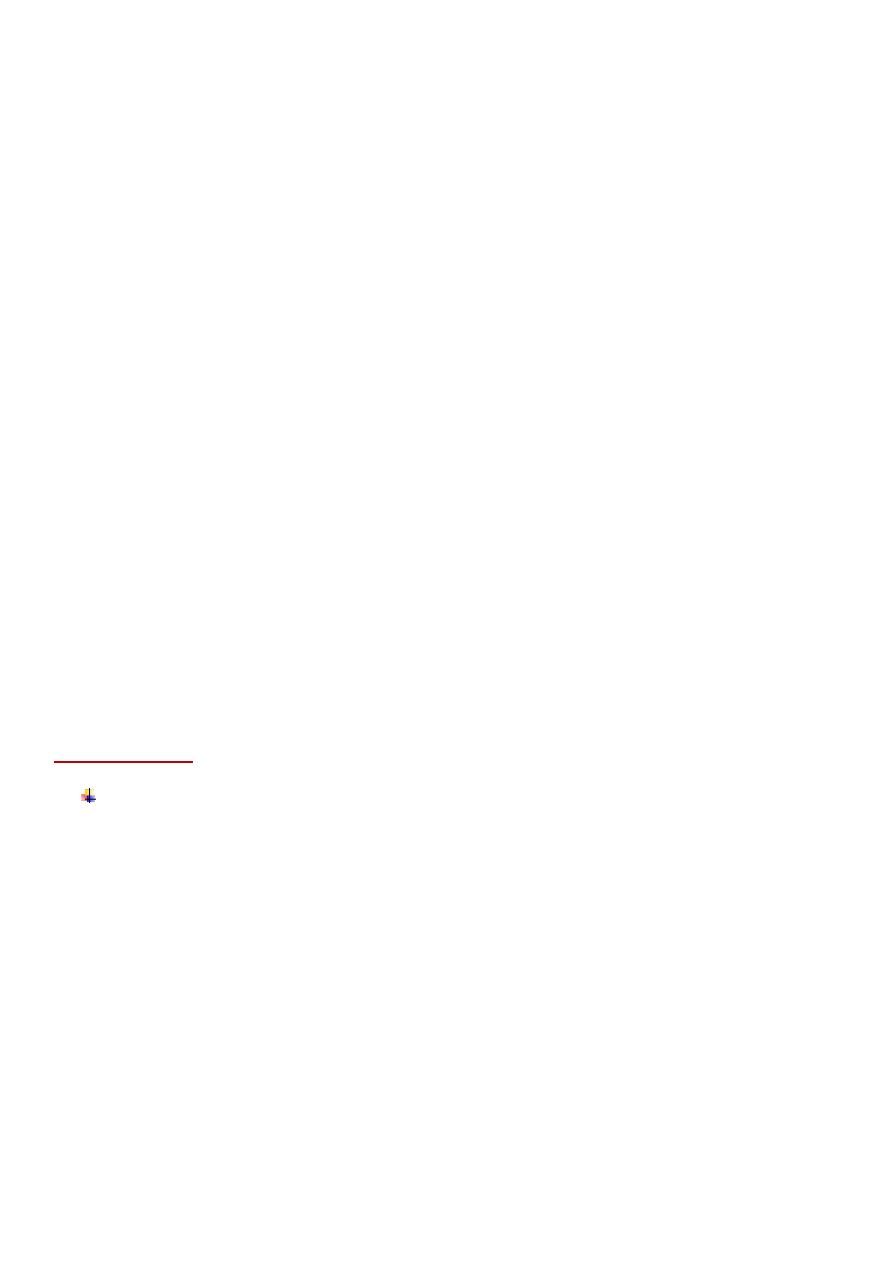

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia: Subcapsular

solid mass with central scar, composed of

the normal components of liver lobule

Central portion of nodular hyperplasia showing the interphase between the fibrous scar

and the hepatocytic nodules.

8

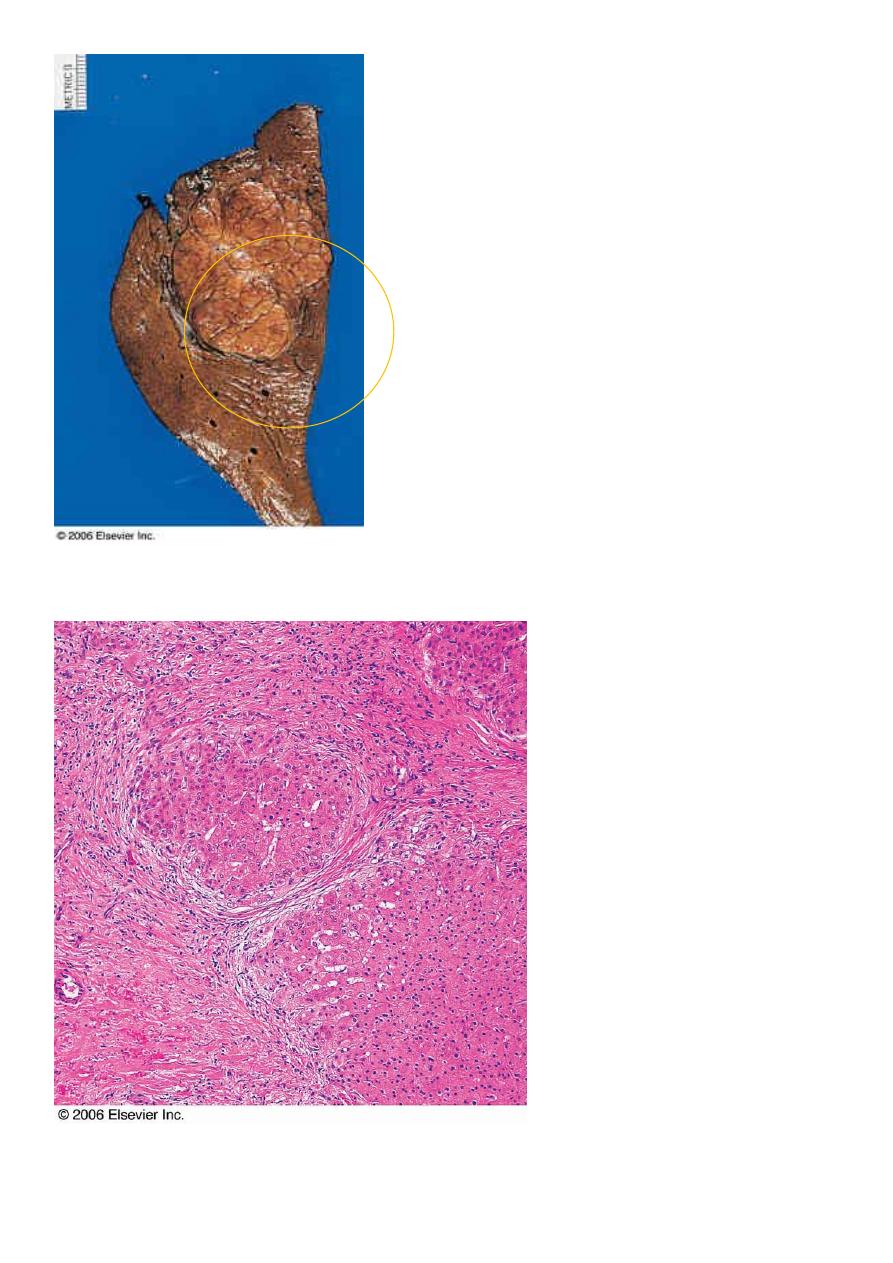

Nodular regenerative hyperplasia

•

(+) development of portal HPN

•

Associated with conditions affecting intrahepatic blood flow

renal transplant, BM

transplant, vasculitis conditions

•

Morphology: plump hepatocytes surrounded by atrophic cells; no fibrosis

Benign Neoplasms

Cavernous hemangioma

•

Most common; blood vessel tumor

•

Soft nodules

< 2 cm diameter

immediately beneath the capsule

•

Clinical significance: mistaken for metastatic tumors

blind percutaneous biopsies

not done

Liver cell adenomas

•

Cell of origin: hepatocytes

•

Young women on oral contraceptives

regress on discontinuance of use

•

Clinical significance:

1. Present as intrahepatic mass mistaken for HCC

2. If subcapsular (+) rupture intraperitoneal hemorrhage

3. May harbor HCC – rare

Normal liver

Hemangioma

Nodular Regenerative Hyperplasia: non-cirrhotic non-neoplastic nodular transformation of the liver parenchyma.

9

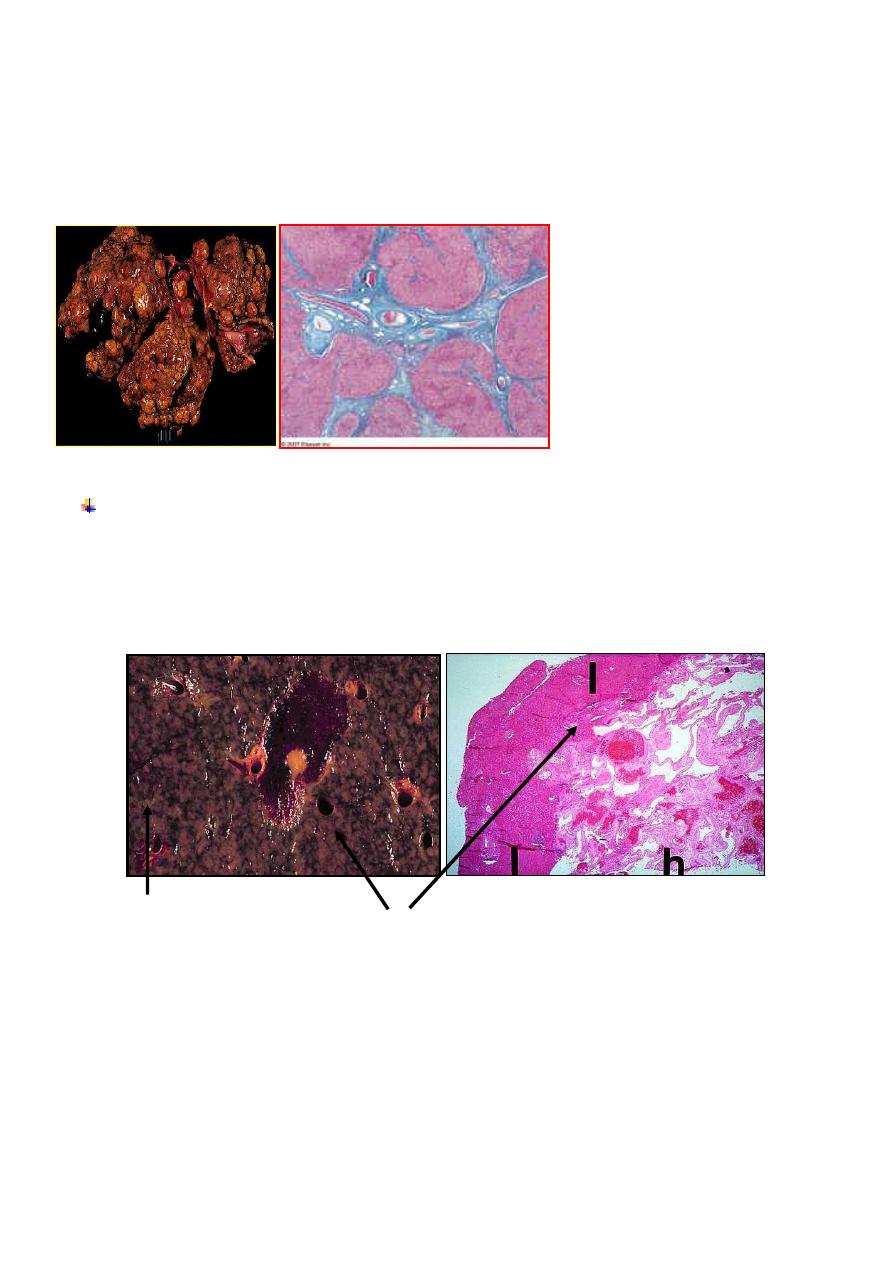

•

Morphology: cords of hepatocytes with clear cytoplasm (w/ glycogen), absent portal tracts &

prominent arterial vessels and draining veins

At the upper right is a well-circumscribed neoplasm that is arising in liver. This

is an hepatic adenoma.

The hepatic adenoma is composed of cells that

closely

resemble

normal

hepatocytes

with

disorganized hepatocyte cords and does not contain

a normal lobular architecture.

Adenoma

Normal liver

11

Malignant Tumors

•

Primary tumors uncommon

often involved in metastatic spread

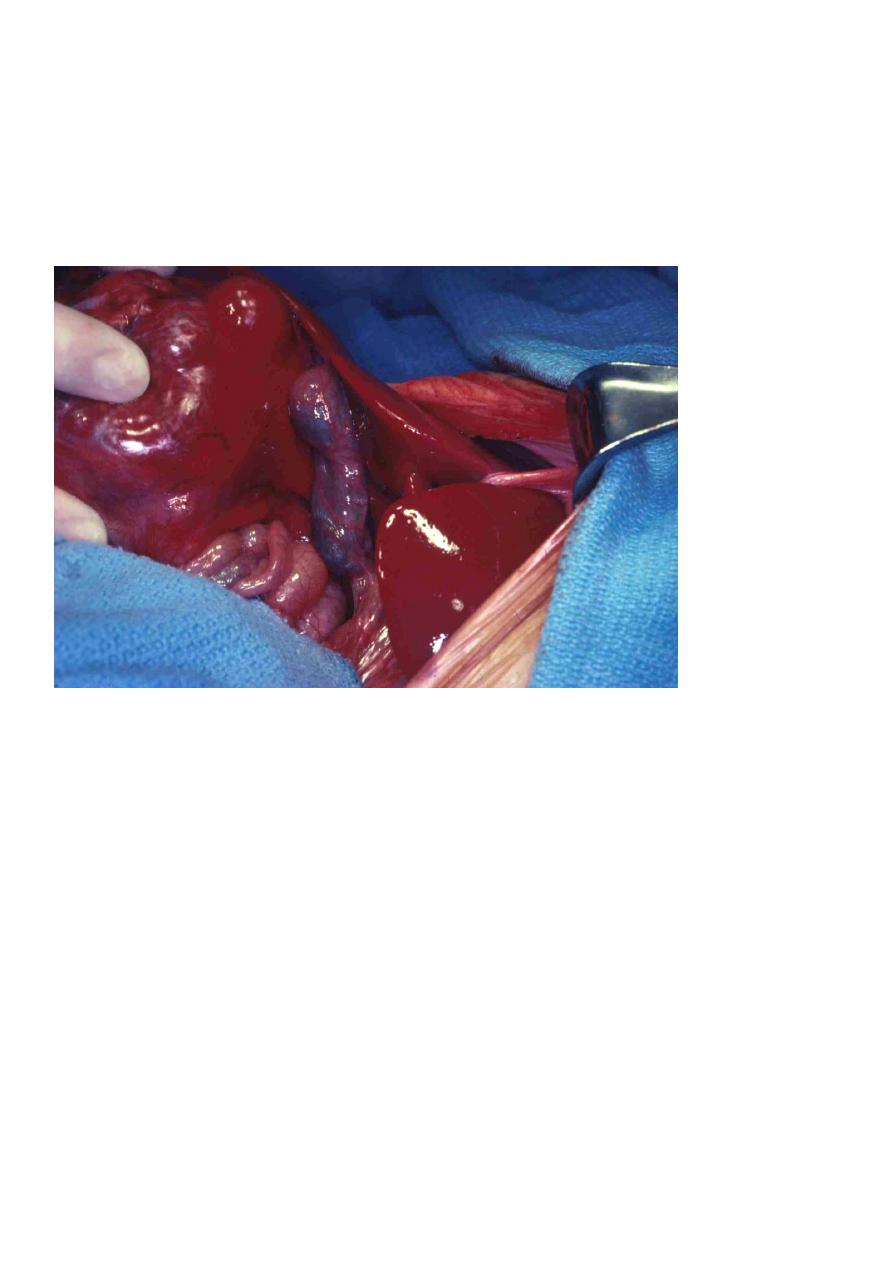

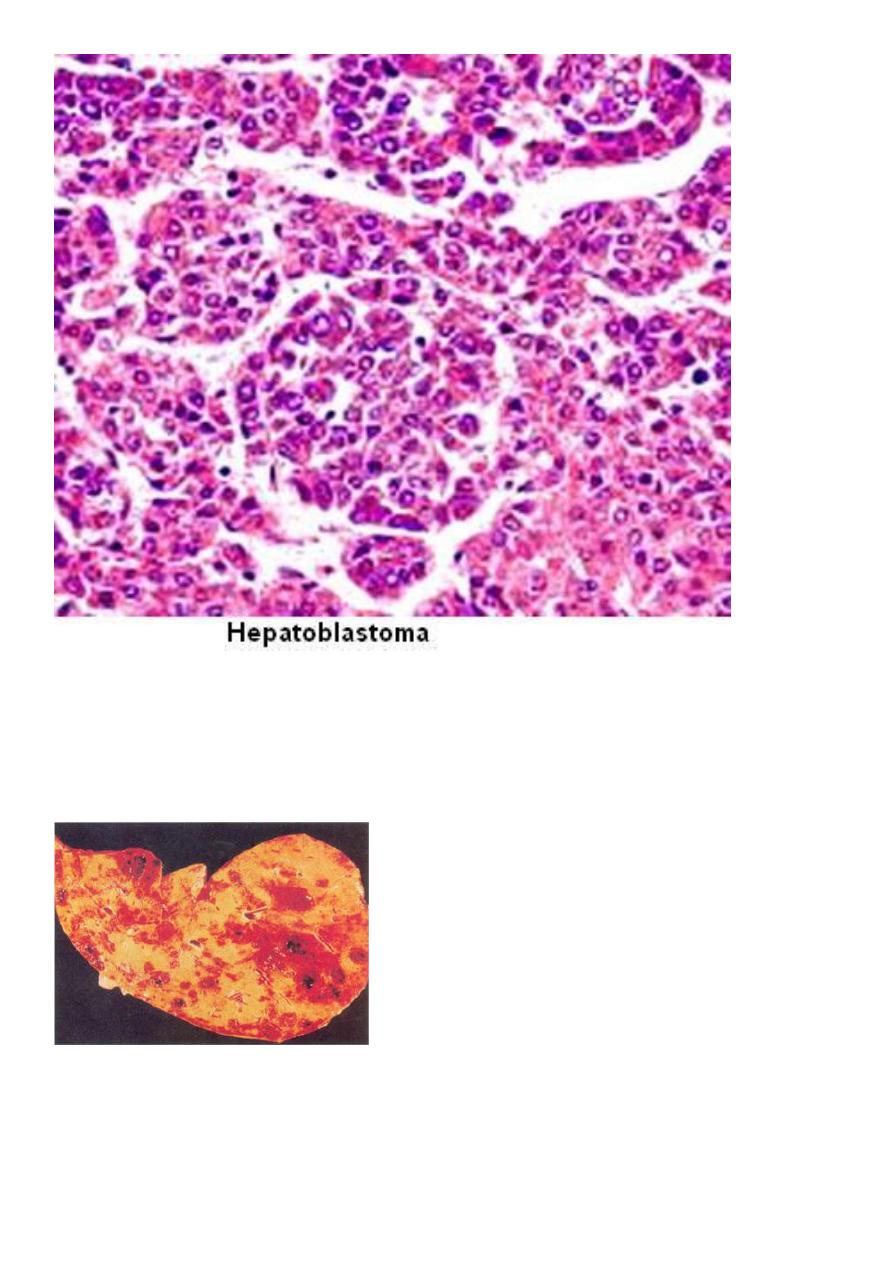

Hepatoblastoma

•

rare; most common liver tumor of young children

•

fatal if not resected

•

(+) activation of

Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway

stabilize mutations of

β-catenin

Hepatoblastoma found to be invading the inferior vena cava at the time of surgical exploration.

11

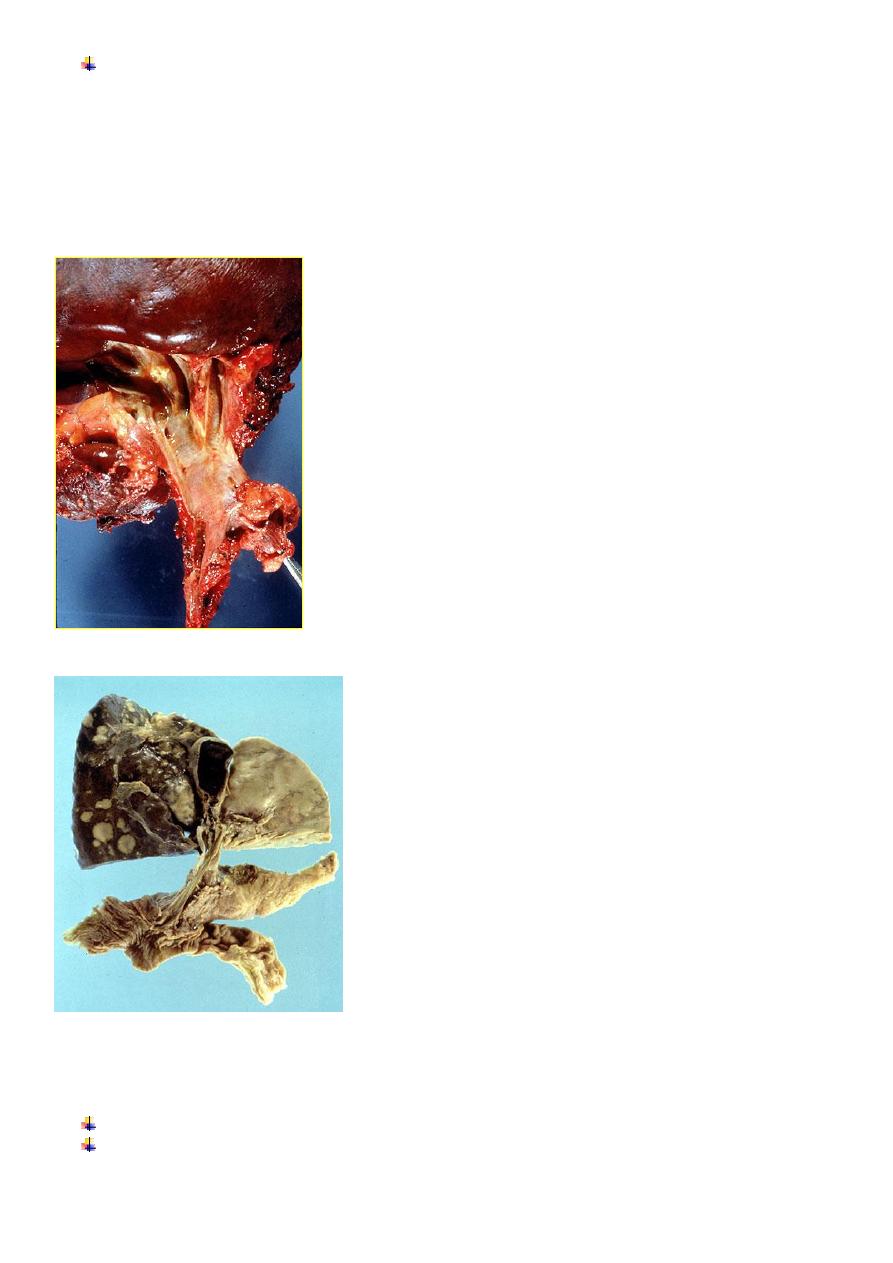

Angiosarcoma

•

rare; malignant endothelial neoplasm

•

associated with exposure to vinyl chloride, arsenic or Thorotrast

•

highly aggressive, metastatic, fatal

Angiosarcoma: Section of liver, showing multiple hemorrhagic tumor deposits.

12

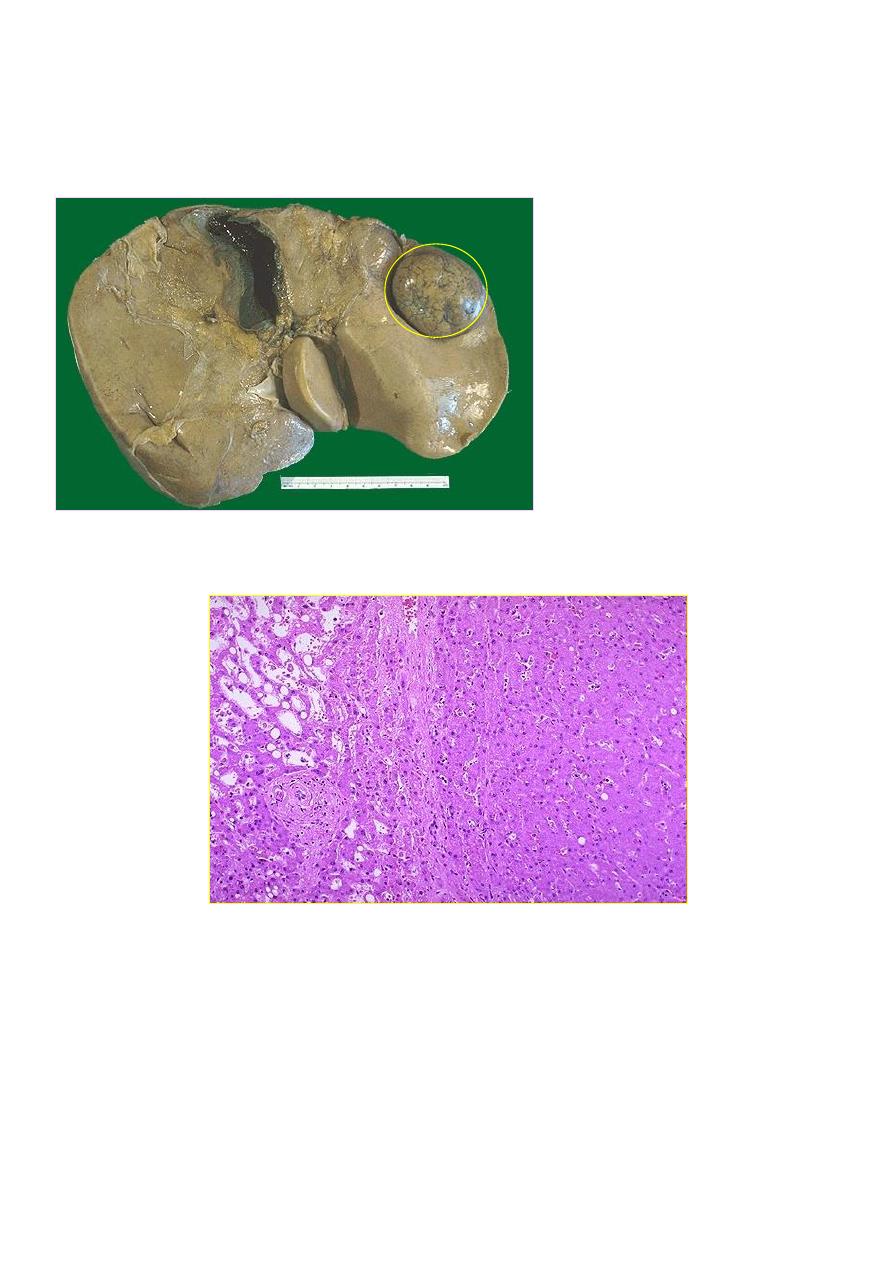

Cholangiocarcinoma

•

malignancy of intrahepatic biliary tract

•

risk factors:

1. Primary sclerosing cholangitis

2. Congenital fibropolycystic diseases of biliary system

3. Previous exposure to Thorotrast

4. Chronic liver fluke infection (O. sinensis)

•

Morphology: resemble sclerosing adenocarcinoma

well-defined glandular & tubular structures

separated by dense collagenous stroma

•

Intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinomas are

classified as either peripheral

or hilar. The hilar variety are

located in the hepatic hilum

region and appear as discrete

masses.

Peripheral cholangiocarcinoma is

the most common and develops in

the interlobular ducts of the liver,

where the interlobular bile duct

branches within the portal triads.

They may be a single or multiple

masses.

13

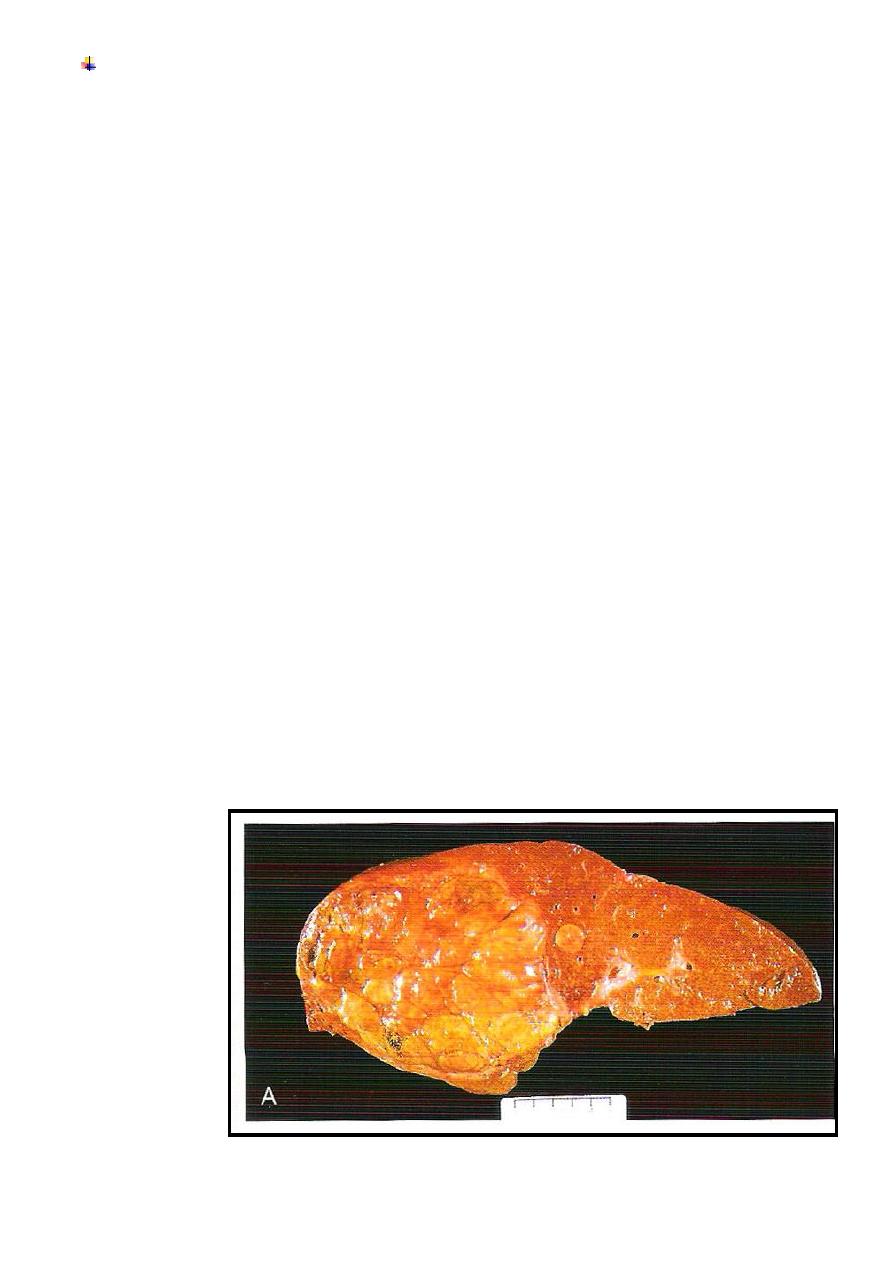

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

• male

preponderance;

20 – 40 y/o

•

Risk factors:

1. Viral infection – chronic HBV & HCV infection no cirrhosis

2. Chronic alcoholism – (+) cirrhosis

3. Food contaminants – aflatoxin from Aspergillus flavus bind covalently with cellular

DNA (+) p53 mutation

•

>85%

occur in countries with high rates of chronic HBV and HCV infections

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver tumour,

the sixth most common cause of cancer worldwide

.

Cirrhosis is present in

75– 90%

of individuals with HCC and is an important risk factor for the disease

The risk is between

1% and 5%

in cirrhosis caused by hepatitis B and C.

There is also an increased risk in cirrhosis due to

haemochromatosis,

alcohol, NASH and α1-antitrypsin deficiency

Chronic hepatitis B infection increases the risk of HCC

100-fold

and is the major risk factor worldwide.

The risk of HCC is 0.4% per year in the absence of cirrhosis and 2–6% in cirrhosis.

The risk is four times higher in HBeAg-positive individuals than in those who are HBeAg-negative.

Hepatitis B

vaccination has led to a

fall in HCC in countries with a high prevalence of

hepatitis B.

The incidence in Europe and North America

has risen recently, probably related to the increased

prevalence of hepatitis C and NASH cirrhosis.

The risk is higher in men and rises with age

Morphology:

Gross

1. Unifocal large mass

2. Multifocal

3. Diffusely infiltrative

14

Morphology:

Microscopic:

Well differentiated trabecular pattern or acinar, pseudo glandular

pattern

Poorly differentiated pleiomorphic with anaplastic giant cells

Clinical features:

•

upper abdominal pain or fullness

•

malaise, fatigue, weight loss

•

hepatomegaly with irregularity or nodularity

Laboratory:

•

increased tumor markers – serum AFP and

serum CEA

not conclusive

false (+)

in non-neoplastic conditions (e.g.

cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis, massive liver

necrosis, fetal neural defects such as

anencephaly)

Investigations

Serum markers (AFP

)

Imaging( US, CT, MRI

)

Role of screening

Screening for HCC, by ultrasound scanning and AFP measurements at 6-month intervals, is indicated in high-risk

patients, such as those with

cirrhosis due to hepatitis B and C, haemochromatosis, alcohol, NASH and α1-antitrypsin

deficiency

.

It may also be indicated in individuals with chronic hepatitis B (who carry an increased risk of HCC, even in the

absence of cirrhosis).

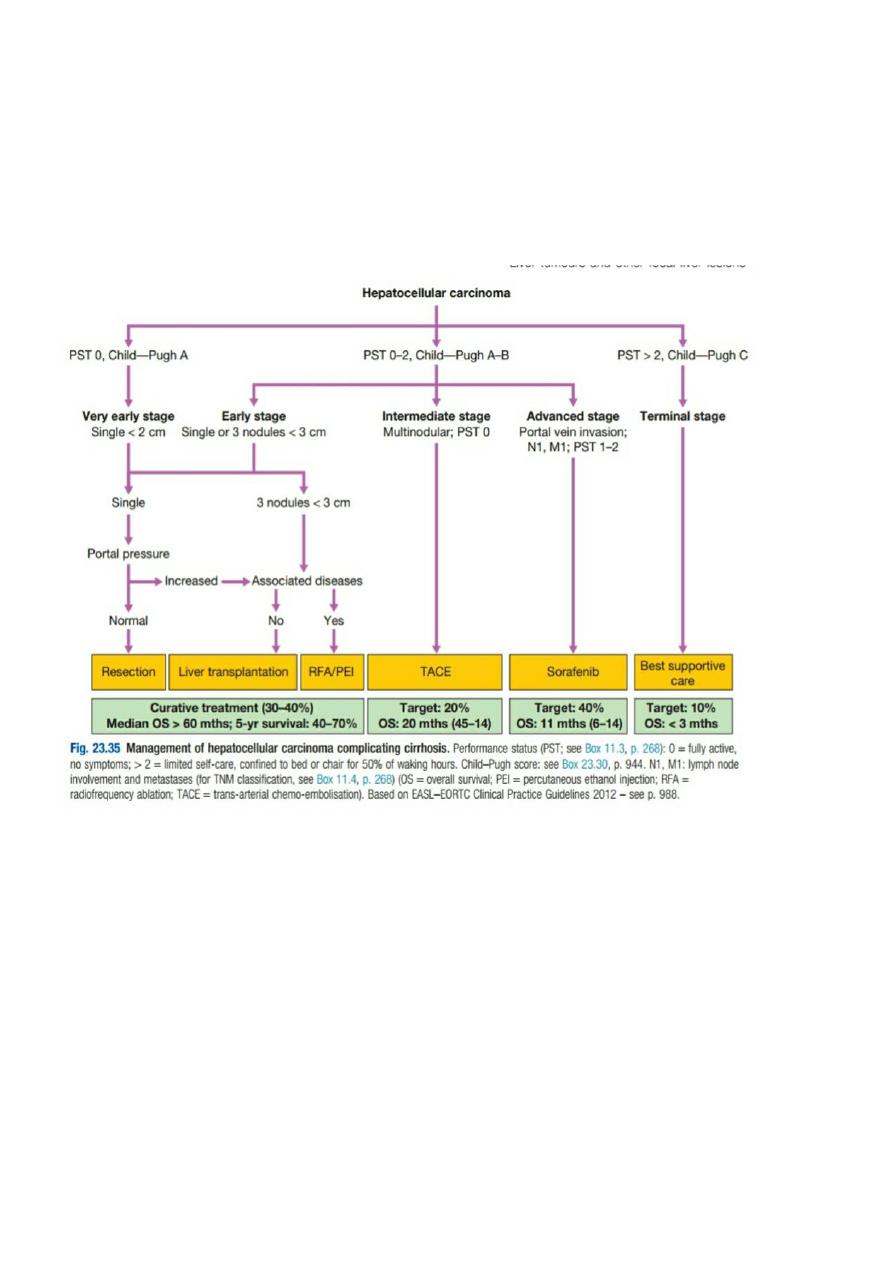

Management

THE PRESENCE OF CIRRHOSIS

,

TUMOUR SIZE

,

MULTICENTRICITY

,

EXTENT OF LIVER DISEASE

15

(C

HILD

–P

UGH SCORE

)

AND PERFORMANCE STATUS DICTATE

APPROPRIATE THERAPY

.

Hepatic resection

Liver transplantation

Percutaneous therapy

Trans-arterial chemo-embolisation

Chemotherapy

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma

This rare variant differs from HCC in that it occurs in young adults, equally in males and females, in the

absence of hepatitis B infection and cirrhosis. The

tumours are often large at presentation and the AFP is usually normal. Histology of the tumour reveals malignant

hepatocytes surrounded by a dense fibrous stroma.

The treatment of choice is surgical resection.

This variant of HCC has a better prognosis following surgery than an equivalent-sized HCC, two-thirds of patients

surviving beyond 5 years

16

Take a home message

In the setting of a cirrhotic patient with a hepatic mass lesion larger than 2 cm in diameter and

suggestive features of hepatocellular carcinoma, an AFP level higher than 200 ng/mL is considered

diagnostic for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hepatocellular carcinoma can be diagnosed with confidence in patients with a serum AFP level

higher than 200 ng/mL and a mass in the liver.

Secondary malignant tumours

These are common and usually originate from carcinomas in the lung, breast, abdomen or pelvis.

They may be single or multiple. Peritoneal dissemination frequently results in ascites

Clinical features

The primary neoplasm is asymptomatic in 50% of patients, being detected on either radiological, endoscopic

or blood biochemistry screening. There is liver enlargement and weight loss; jaundice may be present.

Investigations

A raised ALP activity is the most common biochemical abnormality but LFTs may be normal.

Ascitic fluid, if present, has a high protein content and may be bloodstained;

cytology sometimes reveals malignant cells. Imaging shows filling defects

(laparoscopy

may reveal the tumour and facilitates liver biopsy)

Management

Hepatic resection can improve survival for slow-growing tumours such as colonic carcinomas, and is

an approach that should be actively explored in patients who are fit for liver resection, have had the

primary tumour resected and in whom extrahepatic disease has been excluded.

Patients with neuro-endocrine tumours, such as

gastrinomas, insulinomas and glucagonomas

, and

those with lymphomas may benefit from surgery, hormonal treatment or chemotherapy.

Unfortunately, palliative treatment to relieve pain is all that is available for most patients; this may

include arterial embolisation of the tumour masses.