Hereditary Clotting Factor

Deficiency (Bleeding Disorders )

Dr. Yahya Altufaily

Professor of Pediatrics

Babylon Medical College

Hemophilia A (factor VIII deficincy ) and hemophilia B (factor IX

definciency) are the most common and serious congenital coagulation

factor defiencies .

The clinical findings in hemophilia A and hemophilia B are identical.

Hemophilia C is the bleeding disorder associated with reduced levels

of factor 11 .

Reduced levels of the contact factors(factor 12 ,high molecular-weight

kininogen and prekallikrein) are associated with significant prolongation

of PTT , but are not associated with hemorrhage .

Factor VIII or Factor IX

Deficiency (Hemophilia A or B)

Deficiencies of factors VIII and IX are the most common sever

inherited bleeding disorders.

Pathophysiology:

Factor VIII and IX with phospholipid and calcium , they form the

tenase or factor X activating complex.

Factor X being activated by either the complex of factor VIII and

IX or the complex of tissue factor and factor VII .

Prothrombin time (PT) measures the activation of factor X by

factor VII and is therefore normal in patients with factor VIII and

IX deficiency.

In hemophilia A and B ,due to inadequate thrombin generation

leads to failure to form a tightly cross- linked fibrin clot support the

platelet plug .

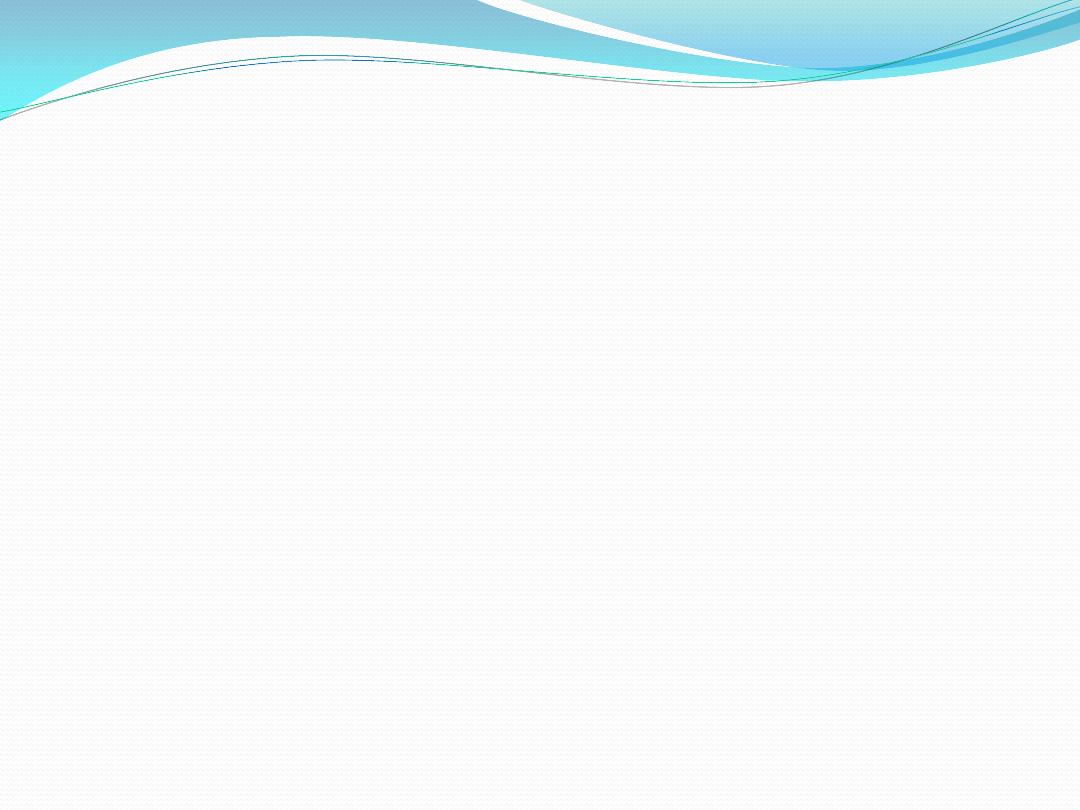

When untreated bleeding occurs in closed space, such as joint

cessation of bleeding may be the result of tamponade.

With open wounds ,in which tamponade cannot occur, bleeding

may result in significant blood loss.

Clinical Manifestations:

Neither factor VIII nor factor IX crosses the placenta , bleeding

symptoms may be present from birth or may occur in the fetus.

Only 2% of neonates with hemophilia sustain intracranial hemorrhages,

and 30% of male infants with hemophilia bleed with circumcision.

In the absence of a positive family history (30% of hemophilia A occurs

by spontaneous mutation), hemophilia may go undiagnosed in the

newborn.

Obvious symptoms, such as easy bruising, intramuscular hematomas,

and hemarthroses, begin when the child starts to cruise.

Bleeding from minor traumatic lacerations of the mouth (torn frenulum)

may persist for hours or days and may cause the parents to seek medical

evaluation.

Although bleeding may occur in any area of the body,

the hallmark of hemophilic bleeding is hemarthrosis.

Bleeding into the joints may be induced by minor trauma; many

hemarthroses are spontaneous.

The earliest joint hemorrhages appear most often in the ankle.

In the older child and adolescent, hemarthroses of the knees and

elbows are also common.

The child's early joint hemorrhages are recognized only after major

swelling and fluid accumulation in the joint space,

but older children complain of a warm, tingling sensation in the

joint as the first sign of an early joint hemorrhage.

Repeated bleeding episodes into the same joint in a patient with

severe hemophilia may result in a “target” joint.

Recurrent bleeding may then become spontaneous because of the

underlying pathologic changes in the joint

Although most muscular hemorrhages are clinically evident

because of localized pain or swelling, bleeding into the iliopsoas

muscle requires specific mention .

A patient may lose large volumes of blood into the iliopsoas

muscle, leading to hypovolemic shock, with only a vague area of

referred pain in the groin.

The hip is held in a flexed, internally rotated position due to

irritation of the iliopsoas.

The diagnosis is made clinically from the inability to extend the hip

but must be confirmed with ultrasonography or CT scan.

Life- threatening bleeding in the patient with hemophilia is caused

by bleeding into vital structures (central nervous system, upper

airway) or by exsanguination (external trauma, gastrointestinal or

iliopsoas hemorrhage).

Argent treatment with clotting factor concentrate for these life-

threatening hemorrhages is essential.

If head trauma is of sufficient concern to suggest radiologic

evaluation, factor replacement should precede radiologic

evaluation.

Life-threatening hemorrhages require replacement therapy to

achieve a level equal to that of normal plasma (100 IU/dL , or

100%).

Patients with mild hemophilia who have factor VIII or factor IX

levels >5 IU/dL

usually do not have spontaneous hemorrhages and

may experience prolonged bleeding after dental work, surgery, or

injuries from moderate trauma and

may not be diagnosed until they are older.

Laboratory Findings and Diagnosis :

A reduced level of factor VIII or factor IX will result in a laboratory

finding of a prolonged PTT.

In severe hemophilia, the PTT value is usually 2-3 times the upper limit

of normal.

Other screening tests of the hemostatic mechanism (platelet count,

bleeding time, PT, thrombin time) are normal.

Unless the patient has an inhibitor to factor VIII or IX, the mixing of

normal plasma with patient plasma results in correction of PTT value.

The specific assay for factors VIII and IX will confirm the

diagnosis of hemophilia.

If correction does not occur on mixing, an inhibitor may be present.

In 25–35% of patients with hemophilia who receive infusions of

factor VIII or factor IX, a factor-specific antibody may develop

(inhibitors).

In such patients, the quantitative Bethesda assay for inhibitors

should be performed to measure the antibody titer.

Differential Diagnosis :

Severe thrombocytopenia;

severe platelet function disorders, such as Bernard-Soulier

syndrome and Glanzmann thrombasthenia; type 3 (severe) von

Willebrand disease; and

vitamin K deficiency.

Genetics and Classification :

Hemophilia occurs in approximately 1 : 5,000 males, with 85%

having factor VIII deficiency and

10–15% having factor IX deficiency.

Hemophilia shows no apparent racial predilection, appearing in all

ethnic groups.

Severe hemophilia is characterized as having <1% activity of the

specific clotting factor, and bleeding is often spontaneous.

Moderate hemophilia have factor levels of 1–5%

and usually require mild trauma to induce bleeding.

Mild hemophilia have levels >5%, may go many years before the

condition is diagnosed, and frequently require significant trauma to cause

bleeding.

Hemostatic level for factor VIII is >30–40%, and for factor IX, it is

>25–30%.

Lower limit of levels for factors VIII and IX in normal individuals is

approximately 50%.

The genes for factors VIII and IX are carried near the terminus of

the long arm of the X chromosome and are therefore X-linked

traits.

Approximately 45–50% of patients with severe

hemophilia A have the same mutation, which can be detected in the

blood of patients or carriers and in the amniotic fluid by molecular

techniques.

In the newborn, factor VIII values may be artificially elevated

because of the acute-phase response elicited by the birth process.

This artificial elevation may cause a mildly affected patient to have

normal or near-normal levels of factor VIII.

Factor IX levels are physiologically low in the newborn.

Through lyonization of the X chromosome, some female carriers of

hemophilia A or B have sufficient reduction of factor VIII or factor IX

to produce mild bleeding disorders.

Levels of these factors should be determined in all known or potential

carriers to assess the need for treatment in the event of surgery or

clinical bleeding.

Because factor VIII is carried in plasma by von Willebrand factor, the

ratio of factor VIII to VWF is sometimes used to diagnose carriers of

hemophilia but may give false-positive or false-negative results.

.

Treatment :

Patients with hemophilia are best managed through comprehensive

hemophilia care centers.

Early, appropriate therapy is the hallmark of excellent hemophilia care

When mild to moderate bleeding occurs, values of factor VIII or factor

IX must be raised to hemostatic levels, in the 35–50% range.

For life-threatening or major hemorrhages, the dose should aim to

achieve levels of 100% activity.

Calculation of the dose of recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) or

recombinant factor IX is as fallows :

Dose of rF VIII(IU) = % Desired (rise in F VIII) × Body weight (Kg) ×

0.5

Prophylaxis is the standard of care for most children with severe

hemophilia, to prevent spontaneous bleeding and early joint

deformities.

If target joints develop, “secondary” prophylaxis is often initiated.

With mild factor VIII hemophilia, the patient's endogenously

produced factor VIII can be released by the administration of

desmopressin acetate .

In patients with moderate or severe factor VIII deficiency, the

stored levels of factor VIII in the body are inadequate, and

desmopressin treatment is ineffective

A concentrated intranasal form of desmopressin acetate, , can also

be used to treat patients with mild hemophilia A.

The dose is 150 µg (1 spray) for children weighing <50 kg and 300

µg (2 sprays) for children and young adults weighing >50 kg.

Desmopressin is not effective in the treatment of factor IX–

deficient hemophilia.

Preliminary trials of factor IX gene therapy are underway with

some encouraging initial results.

Mucosal bleeding may require adjunct use of an antifibrinolytic

such as aminocaproic acid or tranexemic acid.

Once-weekly prophylactic subcutaneous injections of

emicizumab (humanized monoclonal antibody) may be able to

reduce the rate of bleeding in patients with or without factor VIII

inhibitors.

Prophylaxis:

Many patients are now given lifelong prophylaxis to prevent

spontaneous joint bleeding and such programs are initiated with the

1st or 2nd joint hemorrhage.

Treatment is usually provided every 2-3 days to maintain a

measurable plasma level of clotting factor (1–2%) when assayed

just before the next infusion (trough level).

Newer long-acting formulations of factor IX are available that

extend dosing to every week or every other week.

In the older child who is not given primary prophylaxis, secondary

prophylaxis is frequently initiated if a target joint develops.

Supportive Care :

Although it is easy to tell parents that their child should avoid

trauma, this advice is not practical in active children and

adolescents.

Effective measures include anticipatory guidance, including the use

of car seats, seatbelts, and bike helmets and the avoidance of high-

risk behaviors.

Older boys should be counseled to avoid violent contact sports .

Boys with severe hemophilia often sustain hemorrhages in the

absence of known trauma.

Early psychosocial intervention helps the family achieve a

balance between overprotection and permissiveness.

Patients with hemophilia should avoid aspirin and other

nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that affect platelet

function.

The child with a bleeding disorder should receive the appropriate

vaccinations against hepatitis B, even though recombinant

products may avoid exposure to transfusion-transmitted diseases.

Patients exposed to plasma-derived products should be screened

periodically for hepatitis B and C, HIV, and abnormalities in

liver function.

Chronic Complications :

Chronic arthropathy .

The development of an inhibitor to either factor VIII or factor IX .

The risk of transfusion-transmitted infectious diseases.

Inhibitor Formation :

Failure of a bleeding episode to respond to appropriate replacement

therapy is usually the first sign of an inhibitor.

Inhibitors develop in approximately 25–35% of patients with

hemophilia A but only 2–3% of patients with hemophilia B, many

of

Many patients who have an inhibitor will lose it with continued

regular infusions.

Others have a higher titer of antibody with subsequent infusions

and may need to go through desensitization (immune tolerance

induction) programs, in which high doses of factor VIII for

hemophilia A or factor IX for hemophilia B are infused .

Factor IX immune tolerance programs have resulted in nephrotic

syndrome in some patients.

Rituximab, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressives have all

been used as alternate therapy for patients with high inhibitor titers

in whom immune tolerance programs have failed.

If desensitization fails, bleeding episodes are treated with either

recombinant factor VIIa or activated prothrombin complex

concentrates (factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activity).

The use of these products bypasses the inhibitor in many cases but

may increase the risk of thrombosis.

Emicizumab may be another approach for patients with inhibitors

Von Willebrand Disease :

It is the most common inherited bleeding disorder,

Prevalence cited at 1 : 100 to 1 : 10,000 depending on the criteria

used for diagnosis.

Patients with VWD typically present with mucosal bleeding.

A family history of either VWD or bleeding symptoms and

confirmatory laboratory testing are also required for the diagnosis

of VWD.

Epistaxis, easy bruising, and menorrhagia in women are common

complaints.

Symptoms are variable and do not necessarily correlate well with VWF

levels.

Surgical bleeding, particularly with dental extractions or

adenotonsillectomy, is another common presentation.

Severe type 3 VWD may present as mild hemophilia with joint bleeds

and intracranial hemorrhage.

Most patients will have a family history of bleeding. Women are more

likely to be diagnosed with VWD because of the potential for symptoms

with menorrhagia, but men and women are equally likely to have VWD.

However, diagnosis based on symptoms may be difficult, since minor

bruising and epistaxis are not uncommon in childhood .

Classification :

VWD may be caused by quantitative or qualitative defects in VWF.

Mild to moderate quantitative defects are classified as type 1

VWD,

Severe quantitative defects, in which there is no detectable VWF

protein, are classified as type 3 VWD.

The qualitative defects are grouped together as type 2 VWD.

Type 1 VWD is the most common type, accounting for 60–80% of

all VWD patients.

Typical symptoms include mucosal bleeding, such as epistaxis and

menorrhagia, as well as easy bruising and potentially surgical

bleeding.

Patients with type 1 VWD may have low VWF as a result of

increased clearance of their VWF, or type 1C VWD .

Diagnosis of this subtype is important because treatment of these

patients with desmopressin is likely to be ineffective, necessitating

administration of VWF-containing products

.

Type 3 VWD is the most severe form and presents with symptoms

similar to those seen in mild hemophilia.

In type 3 VWD the VWF protein is completely absent.

In addition to mucosal bleeding, patients may experience joint

bleeds or central nervous system hemorrhage.

Some physicians elect to treat patients with prophylaxis, or

modified prophylaxis following injury, given that these

patients typically have very low FVIII (<10 IU/dL).

Laboratory Diagnosis

There are no reliable screening tests for VWD.

Patients with significant bleeding may present with anemia, and

some patients with type 2B VWD and platelet-type pseudo-VWD

may have thrombocytopenia.

The partial thromboplastin time may be prolonged if FVIII is low

but especially in type 1 VWD it is often normal, precluding use of

the PTT as a screening test.

Platelet function analysis has been considered as a screening test

for VWD, but suboptimal sensitivity and

specificity render results difficult to interpret.

Bleeding times are similarly unreliable in diagnosis of VWD.

No single test can reliably diagnose VWD;these include VWF:Ag,

which measures the total amount of VWF protein present,

and VWF activity test, typically using the ristocetin cofactor

activity assay (VWF:RCo ).

VWF levels can be influenced by external factors.

Blood type has long been known to affect VWF, with lower VWF

levels seen in people with blood group O.

Stress, exercise, and pregnancy all increase VWF levels;

therefore a single normal VWF level does not necessarily rule out

the presence of VWD.

Certain diseases, such as hypothyroidism , and medications, such

as valproic acid, can lower VWF levels in affected patients.

Repeat testing may be required to rule out or confirm a diagnosis

of VWD.

Treatment

Treatment of VWD depends on the type of VWD present and the reason

for treatment.

In general, type 1 VWD patients may be treated with

desmopressin , which increases the amount of circulating VWF by

release from storage.

The exceptions are the rare type 1 patient who lacks a response to

desmopressin and patients with type 1C VWD who do respond with an

increase in VWF levels, but whose rapid clearance of circulating

endogenous VWF results in a rapid return to baseline levels.

Treatment of types 2 and 3 VWD requires VWF-containing concentrates

similar to the treatment of hemophilia.

For all types of VWD, adjunct therapy should be considered when

possible, such as the use of antifibrinolytics for oral surgery or

hormonal treatment for menorrhagia.

Local treatment of epistaxis, such as nasal cautery or packing, may

be helpful in some circumstances.

Iron therapy for patients with iron-deficiency anemia may also be

required.

THANK YOU