1

THI QAR U. MEDICAL COLLEGE HEPATOLOGY LECTURES 2017

DEPARTMENT OF INTERNAL MEDICINE Dr. FAEZ KHALAF, SUBSPACIALITY GIT

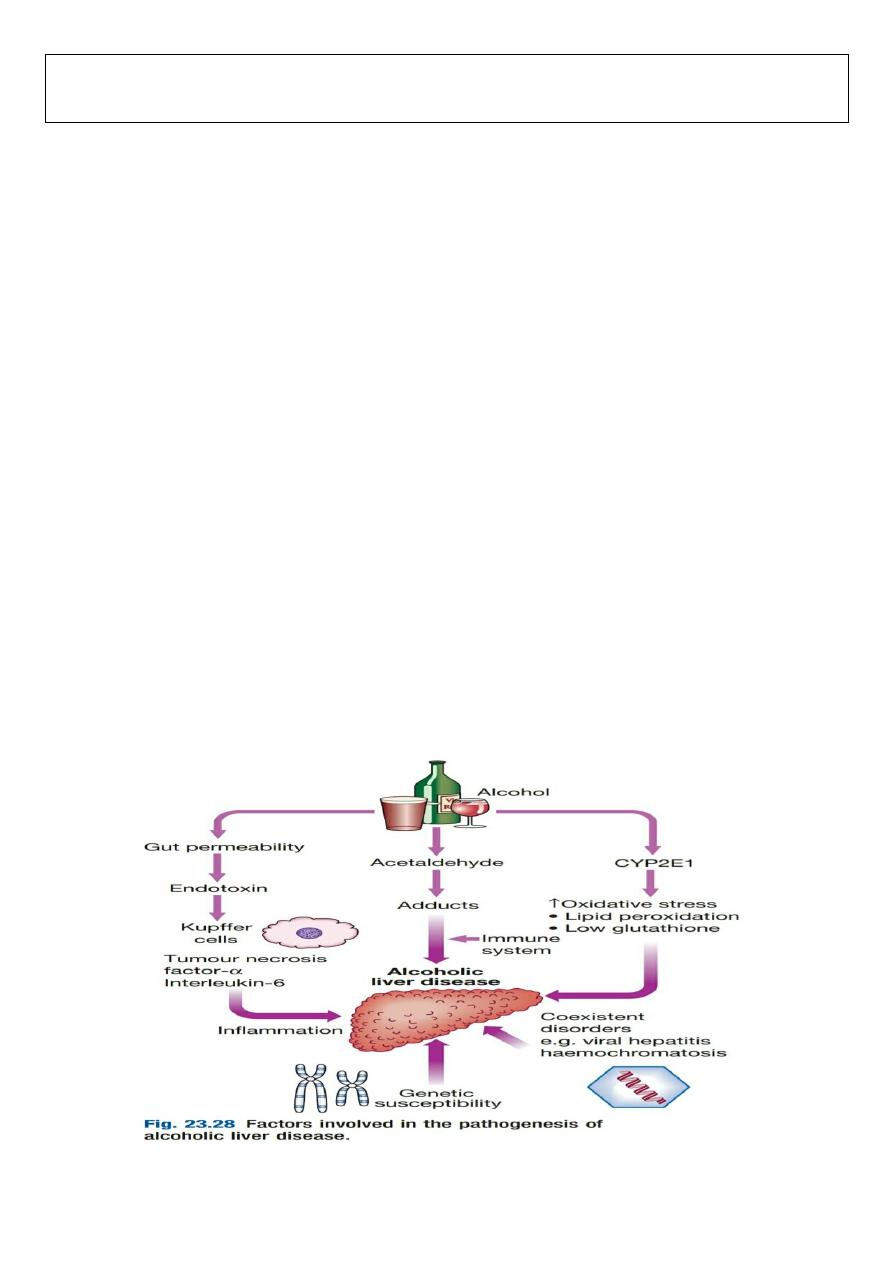

ALCOHOLIC LIVER DISEASE:

Alcohol is one of the most common causes of chronic liver disease worldwide, with consumption continuing to

increase in many countries. Patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) may also have risk factors for other liver

diseases (e.g. coexisting NAFLD or chronic viral hepatitis infection), and these may interact to increase disease

severity. In the UK, a unit of alcohol contains 8 g of ethanol. A threshold of

14 units/week in women and 21

units/week in men is generally considered safe

. The risk threshold for developing ALD is variable but begins at 30

g/day of ethanol. However,

there is no clear linear relationship between dose and liver damage

. For many,

consumption

of more than 80 g/day, for more than 5 years, is required to confer significant risk of advanced liver

disease.

The average alcohol consumption of a man with cirrhosis is 160 g/day for over 8 years

. Some of the risk

factors for ALD are:

•

Drinking pattern

. ALD and alcohol dependence are not synonymous; many of those who develop ALD are not

alcohol-dependent and most dependent drinkers have normal liver function. Liver damage is more likely to occur in

continuous rather than intermittent or ‘binge’ drinkers, as this pattern gives the liver a chance to recover. It is

therefore recommended that people should have at least two alcohol-free days each week. The type of beverage

does not affect risk.

• Gender

. The incidence of alcoholic liver disease is increasing in women, who have higher blood ethanol levels than

men after consuming the same amount of alcohol. This may be related to the reduced volume of distribution of

alcohol.

• Genetics

. Alcoholism is more concordant in monozygotic than dizygotic twins. Whilst polymorphisms in the genes

involved in alcohol metabolism, such as aldehyde dehydrogenase, may alter drinking behaviour, they have not been

linked to ALD. Recently, the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (

PNPLA3) gene

, also known as

adiponutrin, has been implicated in the pathogenesis

of both ALD and NAFLD.

• Nutrition

. Obesity increases the incidence of liver-related mortality by

over fivefold in heavy drinkers

. Ethanol

itself produces 7 kcal/g (29.3 kJ/g) and many alcoholic drinks also contain sugar, which further increases the calorific

value and may contribute to weight gain. Excess alcohol consumption is frequently associated with nutritional

2

Clinical features

ALD has a wide clinical spectrum ranging from mild abnormalities of LFTs on biochemical testing to advanced

cirrhosis.

The liver is often enlarged in ALD, even in the presence of cirrhosis

. Stigmata of chronic liver disease, such

as palmar erythema, are more common in alcoholic cirrhosis than in cirrhosis of other aetiologies

. Alcohol misuse

may also cause damage of other organs. Three types of ALD are recognized (Box 23.53) but these overlap

considerably, as do the pathological changes seen in the liver.

a)Alcoholic fatty liver disease

Alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD) usually presents with elevated transaminases in the absence of hepatomegaly. It

has a good prognosis and steatosis usually disappears after 3 months of abstinence.

b) Alcoholic hepatitis

This presents with jaundice and hepatomegaly; complications of portal hypertension may also be present. It has a

significantly worse prognosis than AFLD. About one third of patients die in the acute episode, particularly those with

hepatic encephalopathy or a prolonged PT. Cirrhosis often coexists; if not present, it is the likely outcome if drinking

continues. Patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis often deteriorate during the first 1–3 weeks in hospital. Even if

they abstain, it may take up to 6 months for jaundice to resolve. In patients presenting with jaundice who

subsequently abstain, the 3- and 5-year survival is 70%. In contrast, those who continue to drink have 3- and 5-year

survival rates of 60% and 34% respectively.

c) Alcoholic cirrhosis

Alcoholic cirrhosis often presents with a serious complication, such as variceal haemorrhage or ascites, and only half

of such patients will survive 5 years from presentation. However, most who survive the initial illness and who

become abstinent will survive beyond 5 years.

Investigations

Investigations aim to establish alcohol misuse,

to exclude alternative or additional coexistent causes of liver disease

and to assess the severity of liver damage

. The clinical history from patient, relatives and friends is important to

establish alcohol misuse duration and severity. Biological markers, particularly

macrocytosis in the absence of

anaemia

, may suggest and support a history of alcohol misuse. A

raised GGT is not specific for alcohol misuse

and

may also be elevated in the presence of other conditions, including NAFLD. The level may not therefore return to

normal with abstinence if chronic liver disease is present, and GGT should not be relied on as an indicator of ongoing

alcohol consumption. The presence of

jaundice may suggest alcoholic hepatitis

. Determining the extent of liver

damage often requires a liver biopsy.

3

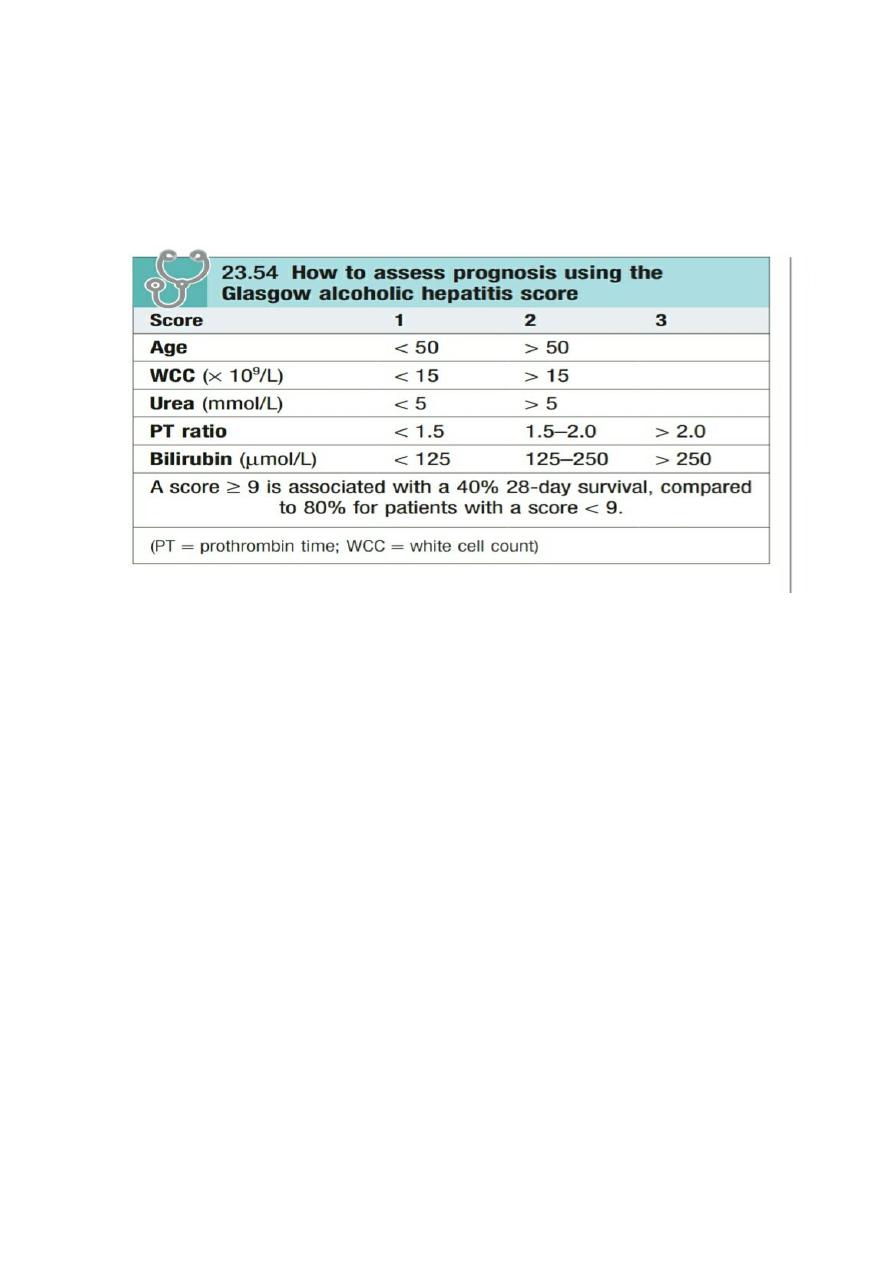

In alcoholic hepatitis,

PT and bilirubin are used to calculate a ‘discriminant function’ (DF), also known as the Maddrey

score, which enables the clinician to assess prognosis (PT = prothrombin time; serum bilirubin in μmol/L is divided

by 17 to convert to mg/dL):

DF Increase in PT (= [4.6 X sec)] +Bilirubin (mg/dL)

A

value over 32 implies severe liver disease with a poor prognosis and is used to guide treatment decisions

. A second

scoring system, the Glasgow score, uses the age, white cell count and renal function, in addition to PT and bilirubin,

to assess prognosis with a cutoff of 9 (Box 23.54).

Management

Cessation of alcohol consumption is the single most important treatment and prognostic factor

. Life-long abstinence

is the best advice. General health and life expectancy are improved when this occurs, irrespective of the stage of

liver disease.

Abstinence is even effective at preventing progression, hepatic decompensation and death once

cirrhosis is present

. In the acute presentation of ALD it is important to identify and

anticipate alcohol withdrawal and

Wernicke’s encephalopathy

, which need treating in parallel with the liver disease and any complications of cirrhosis.

Nutrition

Good nutrition is very important, and enteral feeding via a fine-bore nasogastric tube may be needed in severely ill

patients.

Corticosteroids

These are of value in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (Maddrey’s discriminative score > 32) and increase

survival. A similar improvement in 28-day survival from 52% to 78% is seen when steroids are given to those with a

Glasgow score of more than 9.

Sepsis is the main side-effect of steroids, and existing sepsis and variceal

haemorrhage are the main contraindications to their use.

If the bilirubin has not fallen 7 days after starting steroids,

the drugs are unlikely to reduce mortality and should be stopped.

Pentoxifylline

Pentoxifylline, which has a weak anti-TNF action, may be beneficial in severe alcoholic hepatitis. It reduces the

incidence of hepatorenal failure and its use is not complicated by sepsis. It is not known whether corticosteroids,

pentoxifylline or a combination is superior in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis.

4

Liver transplantation

The role of liver transplantation in the management of ALD remains controversial.

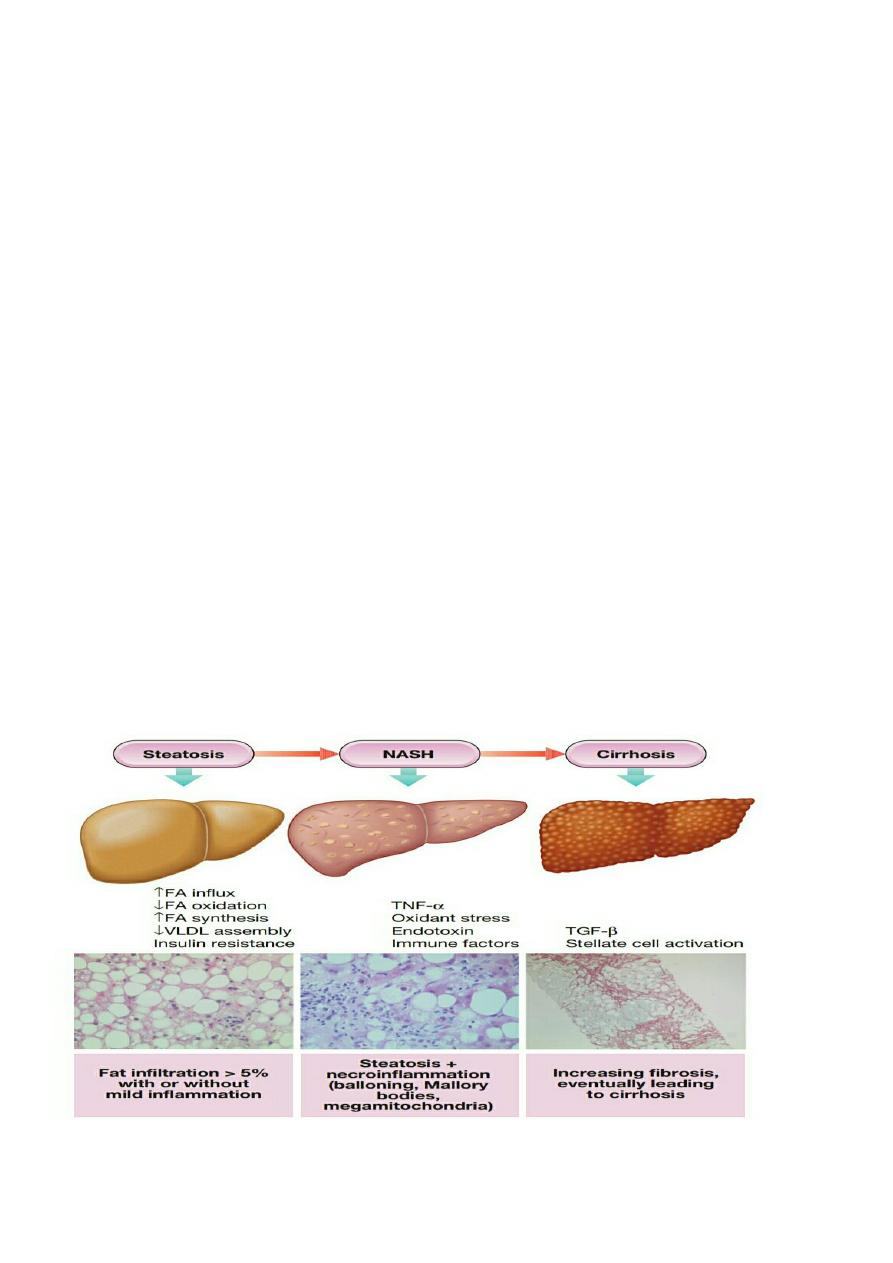

NON-ALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER DISEASE (NAFLD):

(NAFLD) represents a spectrum of liver disease encompassing simple

fatty infiltration (steatosis

), fat and

inflammation (nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, NASH

) and

cirrhosis

, in the absence of excessive alcohol consumption

(typically a threshold of < 20 g/day for women and < 30 g/day for men is adopted). While simple steatosis has not

been associated with liver-related morbidity, NASH is linked with progressive liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and liver cancer,

as well as increased cardiovascular risk

. The true extent of associated morbidity is not well defined however, in one

study NASH was associated with a greater than tenfold increased risk of liver-related death (2.8% vs. 0.2%) and a

doubling of cardiovascular risk over a mean follow-up of 13.7 years.

NAFLD is strongly associated with obesity,

dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance and type 2 (non-insulin dependent) diabetes mellitus

, and so may be considered to

be the hepatic manifestation of the

‘metabolic syndrome’

. Increasingly sedentary lifestyles and changing dietary

patterns mean that the prevalence of obesity and insulin resistance has increased, making NAFLD the leading cause

of liver dysfunction in the non-alcoholic, viral hepatitis-negative population in Europe and North America. Estimates

vary between populations; however, one large European study found

NAFLD to be present in 94% of obese patients

(BMI) > 30 kg/m2), 67% of overweight patients (BMI > 25 kg/m2) and

25% of normal-weight patients

. The overall

prevalence of NAFLD in patients with type 2 diabetes ranges from 40% to 70%. Histological NASH was found in 3–

16% of apparently healthy potential living liver-donors in Europe and 6–15% in USA.

Pathophysiology:

Cellular damage triggers a mixture of immune-mediated hepatocellular injury and cell death, which leads to stellate

cell activation and hepatic fibrosis a combination of several different ‘hits', including:

1. oxidative stress due to free radicals produced during fatty acid oxidation

2. direct lipotoxicity

3. gut-derived endotoxin

4. Cytokine release (TNF-α etc.)

5. Endoplasmic reticulum stress.

5

Clinical features: NAFLD is

frequently asymptomatic

, although it may be associated with f

atigue and mild right upper

quadrant discomfort

. It is

commonly identified as an incidental biochemical abnormality during routine blood tests

.

Alternatively, patients with progressive

NASH may present late in the natural history of the disease with

complications of cirrhosis and portal hypertension, such as variceal haemorrhage, or HCC

. The average age of NASH

patients is 40–50 years (50–60 years for NASH–cirrhosis); however, the emerging epidemic of childhood obesity

means that NASH is present in increasing numbers of younger patients. Most patients with NAFLD have insulin

resistance and exhibit features of the metabolic syndrome. Recognized independent risk factors for disease

progression are age over 45 years, presence of diabetes (or severity of insulin resistance), obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2)

and hypertension. These factors help with identification of ‘high-risk’ patient groups.

NAFLD is also associated with

polycystic ovary syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea and small-bowel bacterial overgrowth.

Investigations

First towards exclusion of excess alcohol consumption and other liver diseases (including viral, autoimmune and

other metabolic causes), and then at confirming the presence of NAFLD, discriminating simple steatosis from NASH

and determining the extent of any hepatic fibrosis that is present.

Biochemical tests

There

is no single diagnostic blood test for NAFLD

. Elevations of serum

ALT and AST are modest

, and usually less

than twice the upper limit of normal.

ALT levels fall as hepatic fibrosis increases and the characteristic AST: ALT ratio

of less than 1 seen in

NASH reverses (AST: ALT > 1) as disease progresses towards cirrhosis

, meaning that

steatohepatitis with advanced disease may be present even in those with normal-range ALT levels

. Other laboratory

abnormalities that may be present include non-specific

elevations of GGT

,

low-titre ANA in 20–30%

of patients and

elevated ferritin levels

.

Imaging

Ultrasound is most often used and provides a qualitative assessment of hepatic fat content, as the liver appears

‘bright’ due to increased echogenicity;

however, sensitivity is limited when fewer than 33% of hepatocytes

are

steatotic. Alternatives include

CT, MRI or MR spectroscopy

, which offer greater sensitivity for detecting lesser

degrees of steatosis, but these are resource intensive and not widely used in routine practice. Currently, no routine

imaging modality can distinguish simple steatosis from steatohepatitis or accurately quantify hepatic fibrosis short of

cirrhosis.

Liver biopsy

Liver

biopsy remains the ‘gold standard’ investigation for diagnosis and assessment of degree of inflammation

and

extent of liver fibrosis. The histological definition of NASH is based on a combination of three lesions (steatosis,

hepatocellular injury and inflammation. with a mainly centrilobular, acinar zone 3, distribution. Specific features

include

hepatocyte ballooning degeneration

with or without acidophil bodies or spotty necrosis and a mild, mixed

inflammatory infiltrate. These may be accompanied by

Mallory–Denk bodies

.

Perisinusoidal fibrosis is a

characteristic feature of NASH.

Histological scoring systems are widely used to assess disease severity semi-

quantitatively. It is important to note that hepatic fat content tends to diminish as cirrhosis develops and so NASH is

likely to be under-diagnosed in the setting of advanced liver disease, where it is thought to be the underlying cause

of 30–75% of cases in which no specific aetiology is readily identified (so-called ‘cryptogenic cirrhosis’

).

Management

Identification of NAFLD should

prompt screening for and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in all patients.

Non-pharmacological treatment

Current treatment comprises lifestyle interventions to promote weight loss and improve insulin sensitivity through

dietary changes and physical exercise.

Sustained weight reduction of 7–10% is associated with significant

improvement in histological and biochemical NASH severity.

6

Pharmacological treatment

No pharmacological agents are currently licensed specifically for NASH therapy

. Treatment directed at coexisting

metabolic disorders,

such as dyslipidaemia and hypertension

, should be given. Although use of HMG-CoA reductase

inhibitors (statins) does not ameliorate NAFLD, there does not appear to be any increased risk of hepatotoxicity or

other side-effects from these agents, and so they may be used to treat dyslipidaemia. Specific insulin-sensitising

agents, in particular

glitazones,

may help selected patients, while positive results

with high-dose vitamin E (800

U/day) have been tempered by evidence that high doses may be associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer

and all-cause mortality, which has limited its use.

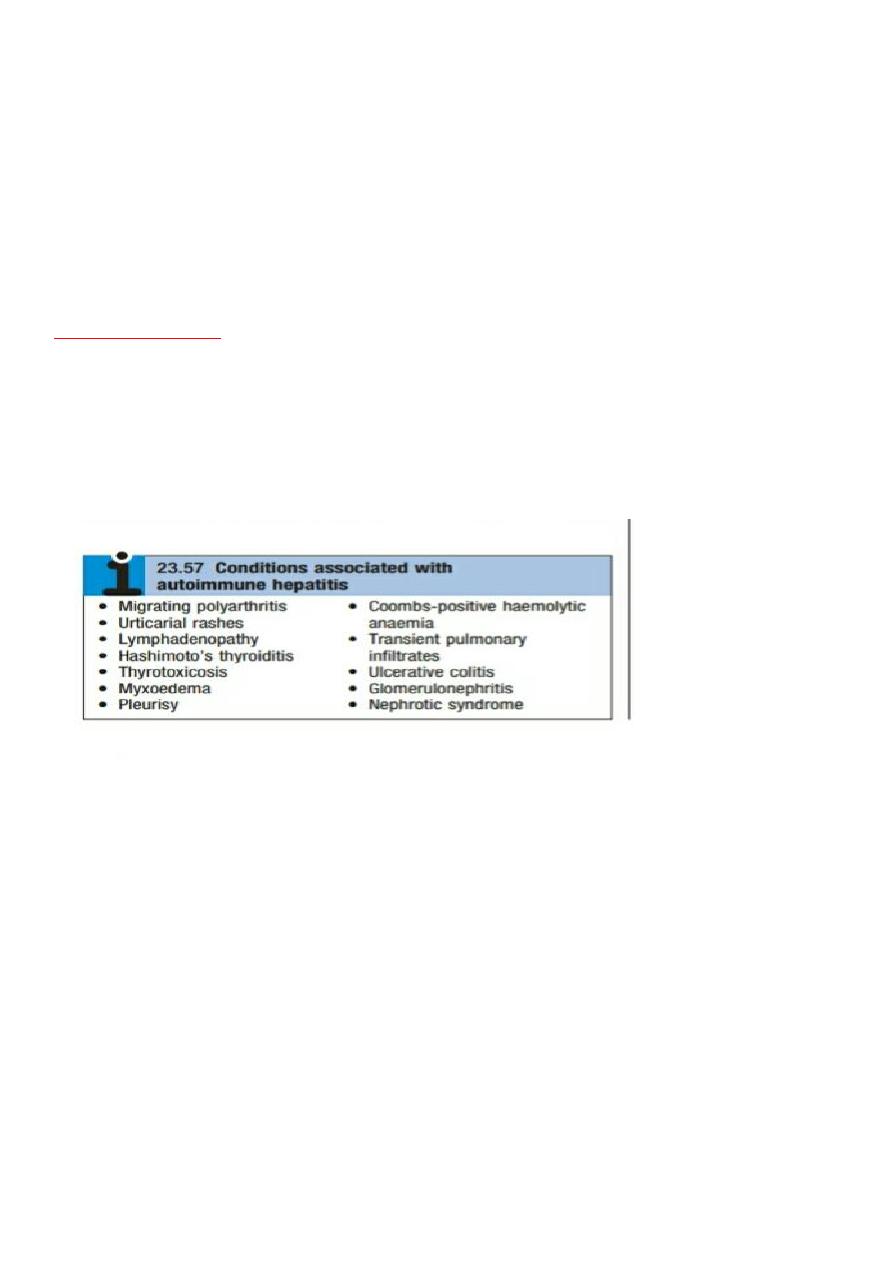

AUTOIMMUNE LIVER AND BILIARY DISEASE:

Autoimmune hepatitis and (primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis).

Autoimmune hepatitis

:

Is a disease of immune-mediated liver injury characterised by the presence of serum antibodies and peripheral

blood T lymphocytes reactive with self-proteins, a strong association with other autoimmune diseases (Box 23.57),

and high levels of serum immunoglobulins – in particular,

elevation of IgG

.

Although most commonly seen in women,

particularly in the second and third decades of life

, it

can develop in either sex at any age

. The reasons for the

breakdown in immune tolerance in autoimmune hepatitis

remain unclear

, although cross-reactivity with viruses such

as HAV and EBV in immunogenetically susceptible individuals (typically those with (

HLA)-DR3 and DR4, particularly

HLA-DRB3*0101 and HLA-DRB1*0401) has been suggested as a mechanism.

Pathophysiology:

Several subtypes of this disorder have been proposed that have differing immunological markers. The formal

classification into disease types has fallen out of favour in recent years.

The most frequently seen autoantibody

pattern is high titre of antinuclear and anti-smooth muscle antibodies, typically associated with IgG

hyperglobulinaemia (type I autoimmune hepatitis in the old classification), frequently seen in young adult females.

Disease characterised by the presence of anti-LKM (liver–kidney microsomal) antibodies

,

recognising cytochrome

P450- IID6 expressed on the hepatocyte membrane, is typically seen in paediatric populations and can be more

resistant to treatment than ANA-positive disease

.

Adult onset of anti-LKM can be seen in chronic HCV infection

. This

was classified as type II disease in the old system. More recently, a pattern of antibody reactivity with antisoluble

liver antigen has been described in typically adult patients, often with aggressive disease and usually lacking

autoantibodies of other specificities.

Clinical features

The onset is

usually insidious

, with

fatigue, anorexia and jaundice

. In about

one-quarter of patients, the onset is

acute, resembling viral hepatitis

, but resolution does not occur. This

acute presentation can lead to extensive liver

necrosis and liver failure

. Other features include

fever, arthralgia, vitiligo and epistaxis

.

Amenorrhea can occur

.

Jaundice is mild to moderate or occasionally absent, but

signs of chronic liver disease, especially spider naevi and

7

hepatosplenomegaly,

can be present. Associated autoimmune disease, such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis or

rheumatoid arthritis, is often present and can modulate the clinical presentation.

Investigations

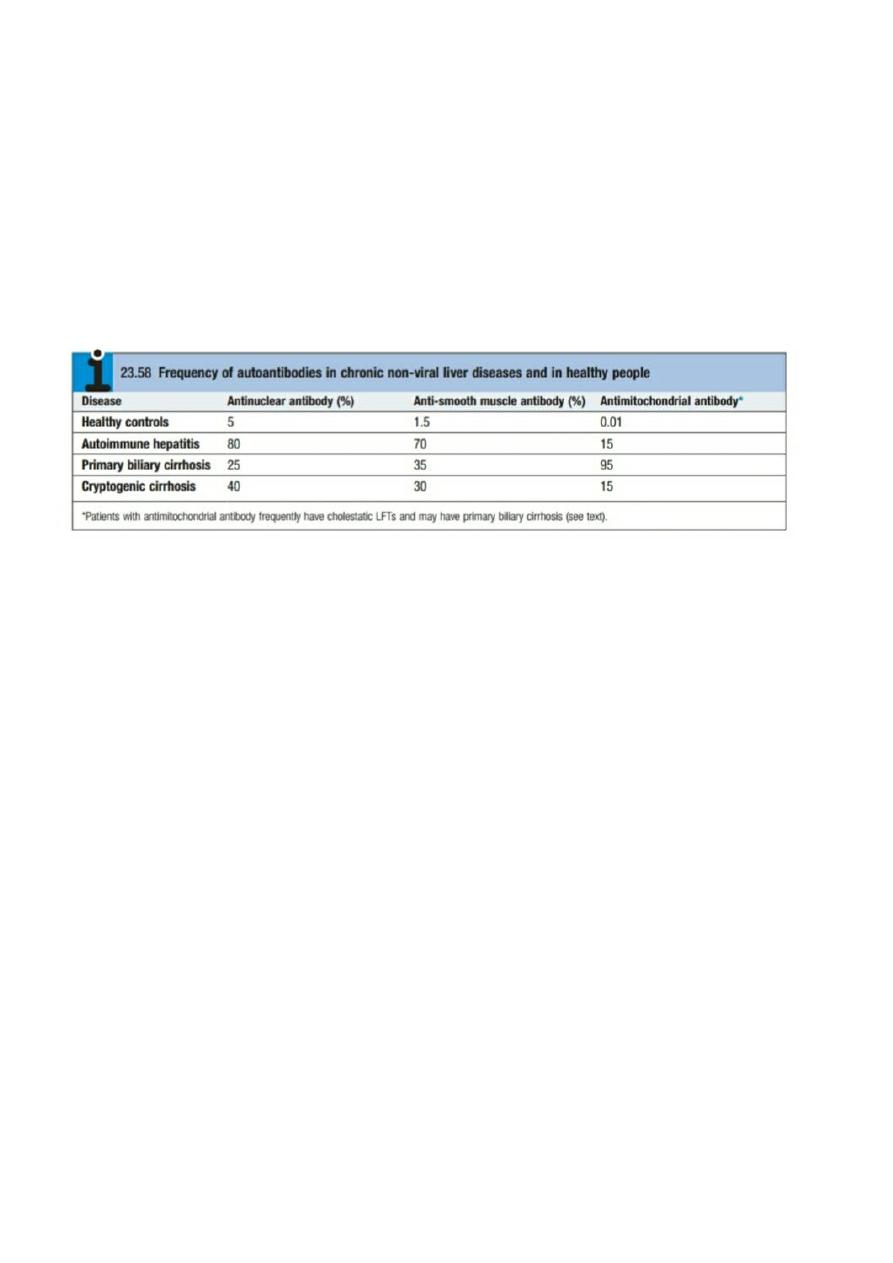

Serological tests for autoantibodies are often positive (Box 23.58), but low titres of these antibodies occur in some

healthy people and in patients with other inflammatory liver diseases.

ANA

also occur in connective tissue diseases

and other autoimmune diseases (with an identical pattern of homogenous nuclear staining) while anti-smooth

muscle antibody has been reported in infectious mononucleosis and a variety of malignant diseases. Anti-

microsomal antibodies

(anti-LKM)

occur particularly in children and adolescents.

Elevated serum IgG levels

are an

important diagnostic and treatment response feature if present, but the diagnosis is still possible in the presence of

normal IgG levels. If the diagnosis of

autoimmune hepatitis is suspected, liver biopsy should be performed. It

typically shows interface hepatitis, with or without cirrhosis

.

Management

Treatment with corticosteroids is life-saving in autoimmune hepatitis, particularly during exacerbations of active and

symptomatic disease

. Initially,

prednisolone 40 mg/day is given orally

; the dose is then gradually reduced as the

patient and LFTs improve. Maintenance therapy should only be instituted once LFTs are normal (as well as IgG if

elevated). Approaches to maintenance include

reduced-dose prednisolone (ideally below 5–10 mg/day

), usually in

the context of azathioprine 1.0–1.5 mg/kg/day

. Azathioprine can also be used as the sole maintenance

immunosuppressive agent in patients with low-activity disease. Newer agents such as mycophenolate mofetil

(MMF)

are increasingly being used but formal evidence to inform practice in this area is lacking. Patients should be

monitored for acute exacerbations (LFT and IgG screening with patients alerted to the possible symptoms) and such

exacerbations should be treated with corticosteroids

. Although treatment can significantly reduce the rate of

progression to cirrhosis, end-stage disease can be seen in patients despite treatment.