Intestinalobstruction

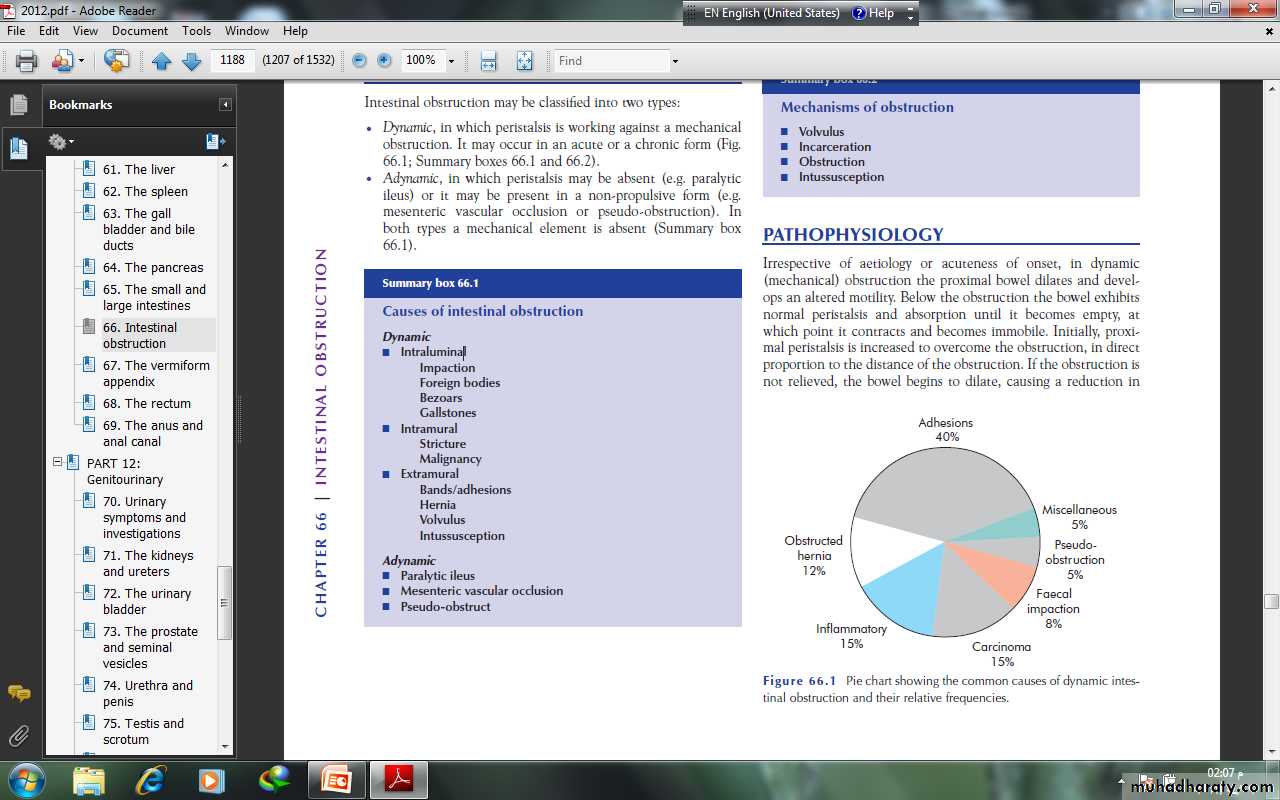

CLASSIFICATIONIntestinal obstruction may be classified into two types:• Dynamic, in which peristalsis is working against a mechanicalobstruction. It may occur in an acute or a chronic form.• Adynamic, in which peristalsis may be absent (e.g. paralyticileus) or it may be present in a non-propulsive form (e.g.mesenteric vascular occlusion or pseudo-obstruction). Inboth types a mechanical element is absent.PATHOPHYSIOLOGY In dynamic (mechanical) obstruction the proximal bowel dilates and develops an altered motility. Below the obstruction the bowel exhibits normal peristalsis and absorption until it becomes empty, at which point it contracts and becomes immobile. Initially, proximal peristalsis is increased to overcome the obstruction, in direct proportion to the distance of the obstruction. If the obstruction is not relieved, the bowel begins to dilate, causing a reduction inperistaltic strength, ultimately resulting in flaccidity and paralysis.This is a protective phenomenon to prevent vascular damage secondary to increased intraluminal pressure.

The distension proximal to an obstruction is produced by twofactors:• Gas: there is a significant overgrowth of both aerobic andanaerobic organisms, resulting in considerable gas production.Following the reabsorption of oxygen and carbon dioxide, themajority is made up of nitrogen (90%) and hydrogen sulphide.• Fluid: this is made up of the various digestive juices. Followingobstruction, fluid accumulates within the bowel wall and anyexcess is secreted into the lumen, whilst absorption from thegut is retarded. Dehydration and electrolyte loss are thereforedue to:– reduced oral intake;– defective intestinal absorption;– losses as a result of vomiting;– sequestration in the bowel lumen.

STRANGULATIONWhen strangulation occurs, the viability of the bowel is threatenedsecondary to a compromised blood supply

STRANGULATIONWhen strangulation occurs, the viability of the bowel is threatenedsecondary to a compromised blood supply The venous return is compromised before the arterial supply. Theresultant increase in capillary pressure leads to local mural distensionwith loss of intravascular fluid and red blood cells intramurallyand extraluminally. Once the arterial supply is impaired,haemorrhagic infarction occurs.

As the viability of the bowel iscompromised there is marked translocation and systemic exposureto anaerobic organisms with their associated toxins. Themorbidity of intraperitoneal strangulation is far greater than withan external hernia, which has a smaller absorptive surface.

The morbidity and mortality associated with strangulation aredependent on age and extent. In strangulated external hernias thesegment involved is short and the resultant blood and fluid loss issmall. When bowel involvement is extensive the loss of blood andcirculatory volume will cause peripheral circulatory failure.

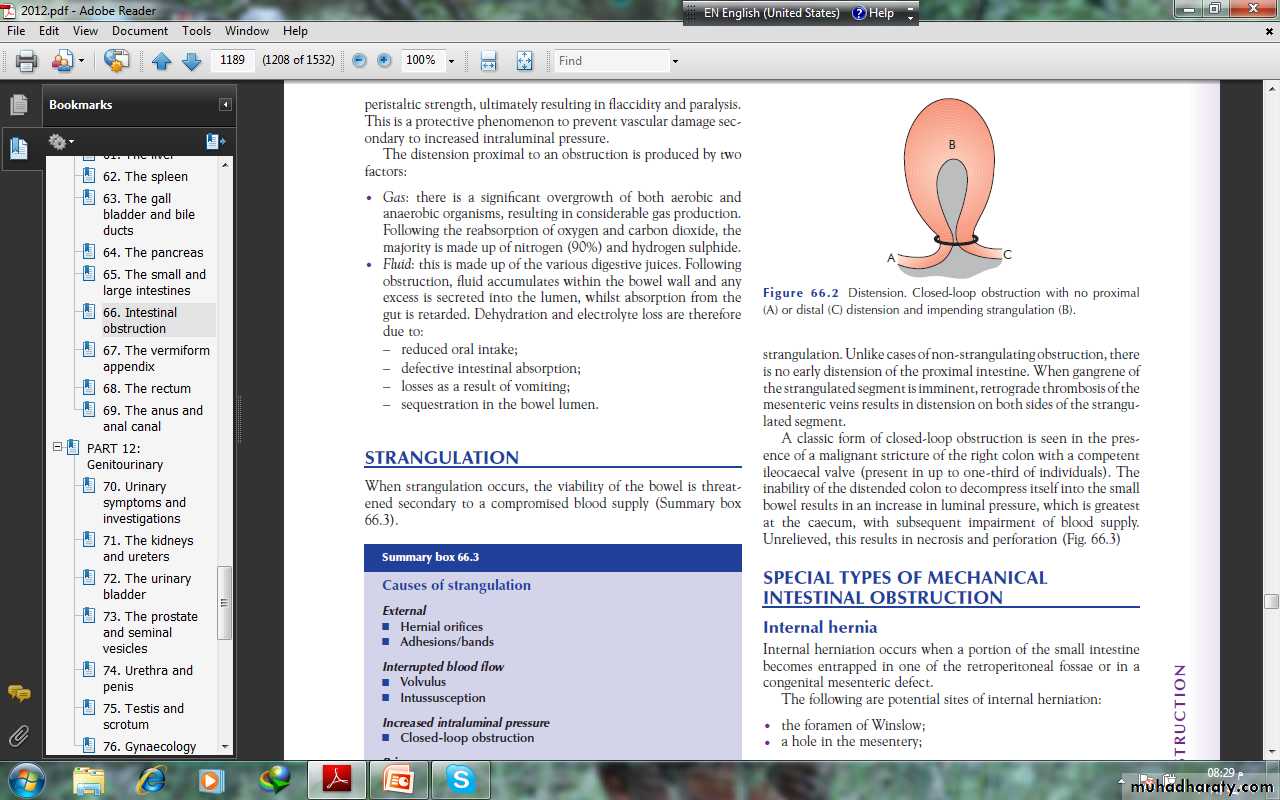

Closed-loop obstructionThis occurs when the bowel is obstructed at both the proximal anddistal points . It is present in many cases of intestinalstrangulation. Unlike cases of non-strangulating obstruction, thereis no early distension of the proximal intestine. When gangrene ofthe strangulated segment is imminent, retrograde thrombosis of the mesenteric veins results in distension on both sides of the strangulated segment.

A classic form of closed-loop obstruction is seen in the presenceof a malignant stricture of the right colon with a competentileocaecal valve (present in up to one-third of individuals)

The inability of the distended colon to decompress itself into the small bowel results in an increase in luminal pressure, which is greatest at the caecum, with subsequent impairment of blood supply. Unrelieved, this results in necrosis and perforation

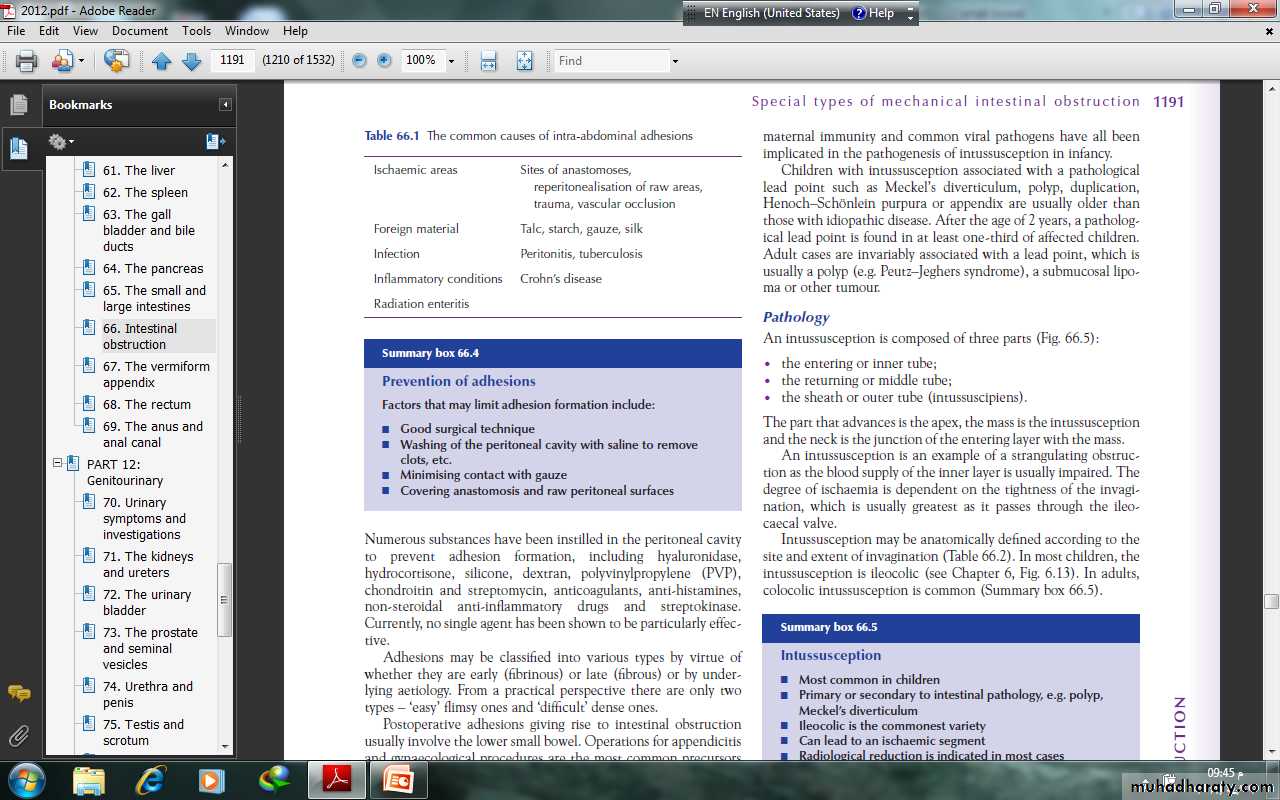

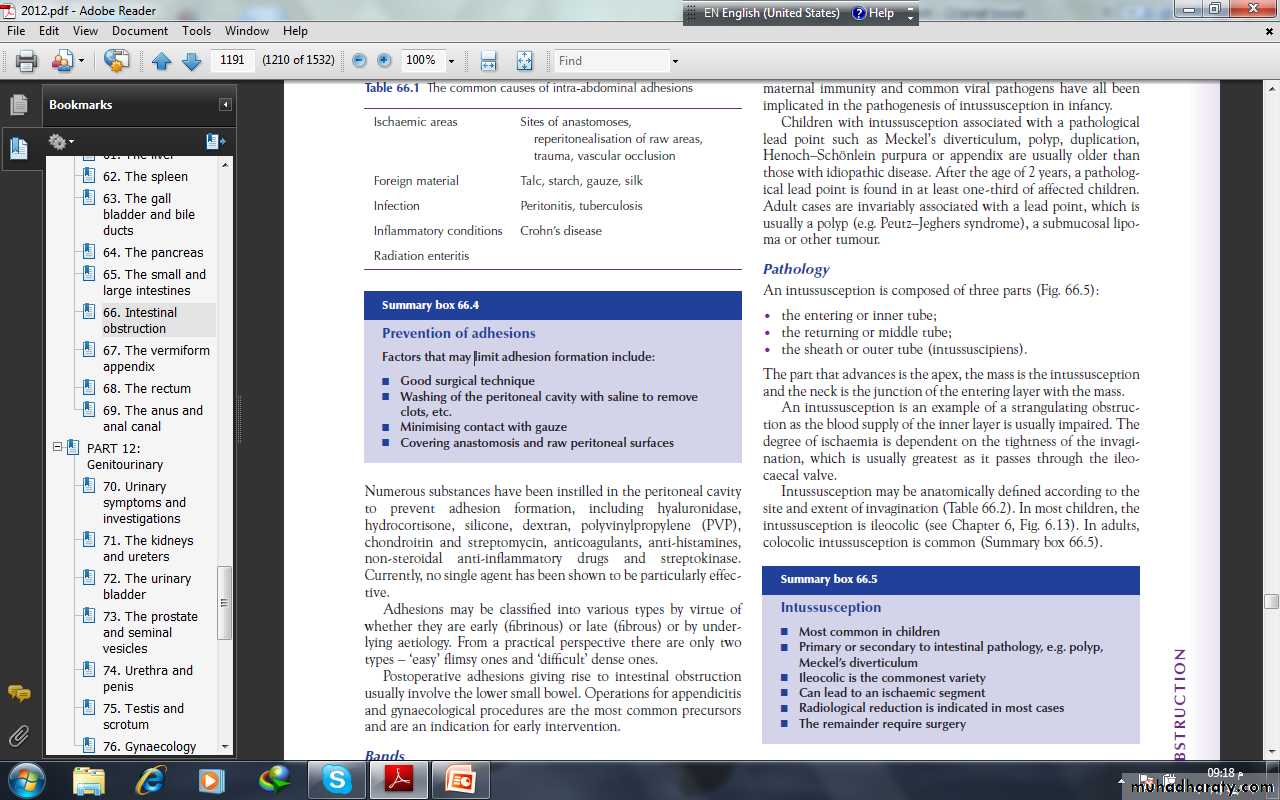

SPECIAL TYPES OF MECHANICALINTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION Obstruction by adhesions and bandsAdhesionsIn western countries where abdominal operations are common,adhesions and bands are the most common cause of intestinalobstruction. Furthermore, in the early postoperative period, theonset of such a mechanical obstruction may be difficult to differentiate from paralytic ileus.

Any source of peritoneal irritation results in local fibrin production,which produces adhesions between apposed surfaces.Early fibrinous adhesions may disappear when the cause isremoved or they may become vascularised and be replaced bymature fibrous tissue.

There are several factors that may limit adhesion formation

Numerous substances have been instilled in the peritoneal cavityto prevent adhesion formation, including hyaluronidase,hydrocortisone, silicone, dextran, polyvinylpropylene (PVP), anticoagulants, anti-histamines, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Postoperative adhesions giving rise to intestinal obstructionusually involve the lower small bowel. Operations for appendicitisand gynaecological procedures are the most common precursorsand are an indication for early intervention

Bands This may be:• congenital, e.g. obliterated vitellointestinal duct;• a string band following previous bacterial peritonitis;• a portion of greater omentum, usually adherent to theparietes.

Acute intussusceptionThis occurs when one portion of the gut becomes invaginatedwithin an immediately adjacent segment; almost invariably, it isthe proximal into the distal.The condition is encountered most commonly in children,with a peak incidence between 5 and 10 months of age. About90% of cases are idiopathic but an associated upper respiratorytract infection or gastroenteritis may precede the condition. It isbelieved that hyperplasia of Peyer’s patches in the terminal ileummay be the initiating event. Weaning, loss of passively acquired maternal immunity and common viral pathogens have all beenimplicated in the pathogenesis of intussusception in infancy.

Children with intussusception associated with a pathologicallead point such as Meckel’s diverticulum, polyp, duplication,Henoch–Schِnlein purpura or appendix are usually older thanthose with idiopathic disease. After the age of 2 years, a pathological lead point is found in at least one-third of affected children.Adult cases are invariably associated with a lead point, which isusually a polyp (e.g. Peutz–Jeghers syndrome), a submucosal lipoma or other tumour.

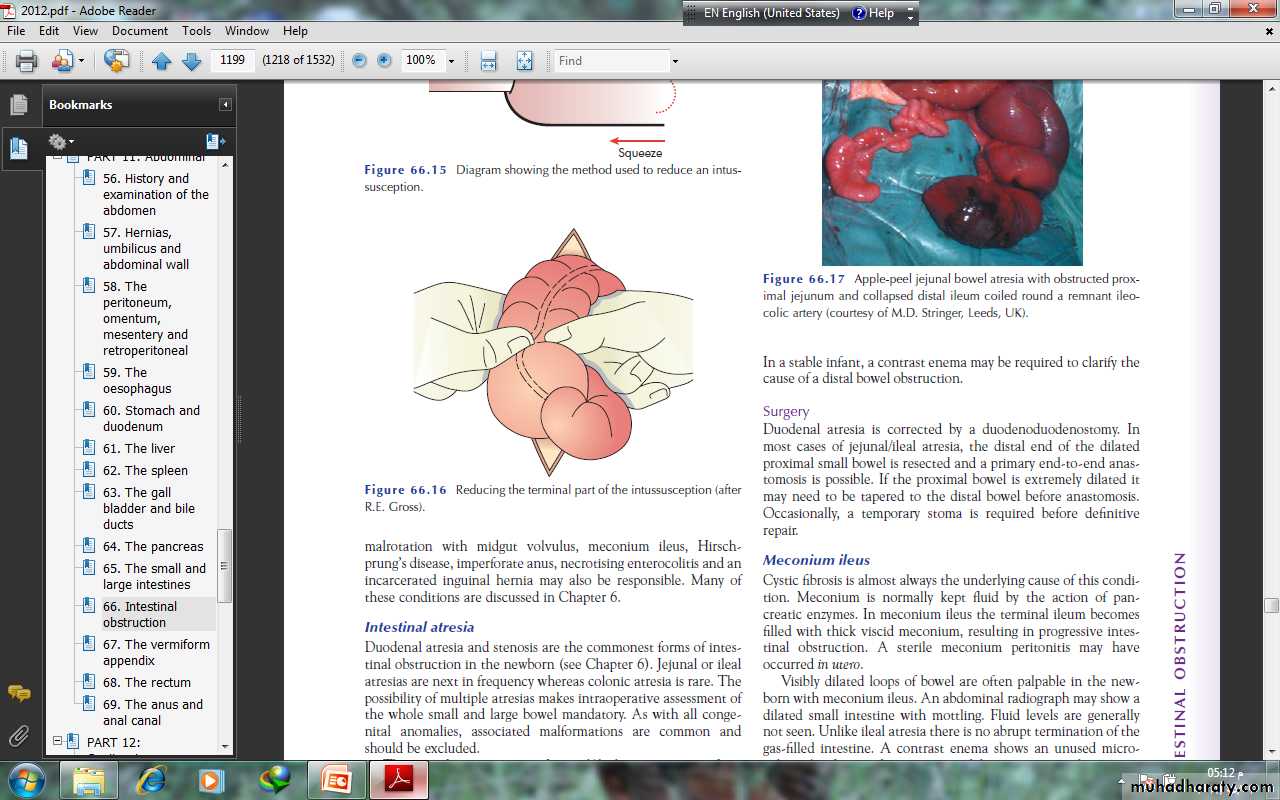

PathologyAn intussusception is composed of three parts :• the entering or inner tube;• the returning or middle tube;• the sheath or outer tube (intussuscipiens).The part that advances is the apex, the mass is the intussusceptionand the neck is the junction of the entering layer with the mass.An intussusception is an example of a strangulating obstructionas the blood supply of the inner layer is usually impaired. Thedegree of ischaemia is dependent on the tightness of the invagination,which is usually greatest as it passes through the ileocaecalvalve.Intussusception may be anatomically defined according to thesite and extent of invagination . In most children, theintussusception is ileocolic . colocolic intussusception is common

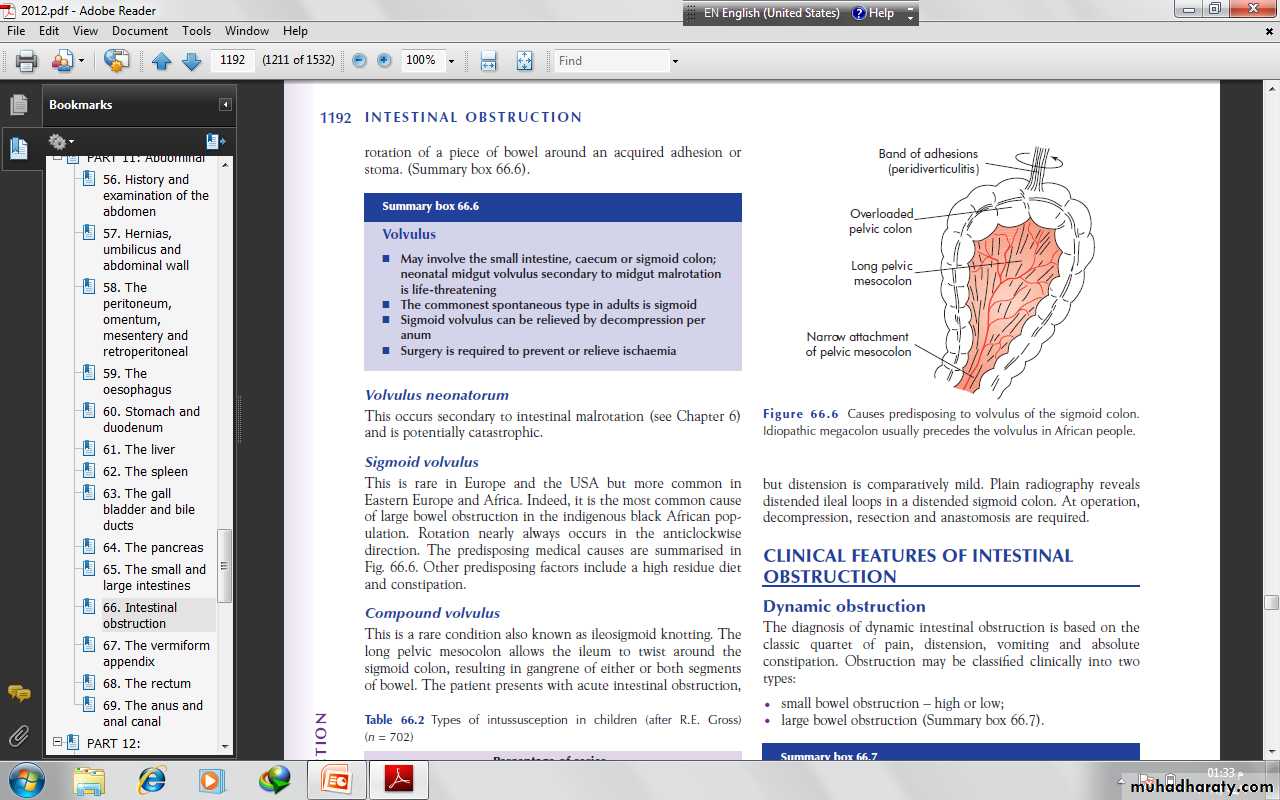

VolvulusA volvulus is a twisting or axial rotation of a portion of bowelabout its mesentery. When complete it forms a closed loop ofobstruction with resultant ischaemia secondary to vascular occlusion.Volvuli may be primary or secondary. The primary form occurssecondary to congenital malrotation of the gut, abnormal mesenteric attachments or congenital bands. Examples include volvulus neonatorum, caecal volvulus and sigmoid volvulus. Asecondary volvulus, which is the more common variety, is due to rotation of a piece of bowel around an acquired adhesion orstoma.

Sigmoid volvulusThis is rare in Europe and the USA but more common inEastern Europe and Africa. Indeed, it is the most common causeof large bowel obstruction in the indigenous black African population. Rotation nearly always occurs in the anticlockwisedirection.

Internal herniaInternal herniation occurs when a portion of the small intestinebecomes entrapped in one of the retroperitoneal fossae or in acongenital mesenteric defect.The following are potential sites of internal herniation:• the foramen of Winslow;• a hole in the mesentery;

• a hole in the transverse mesocolon;• defects in the broad ligament;• congenital or acquired diaphragmatic hernia;• duodenal retroperitoneal fossae • caecal/appendiceal retroperitoneal fossae • intersigmoid fossa. Internal herniation in the absence of adhesions is uncommonand a preoperative diagnosis is unusual

Obstruction from enteric stricturesSmall bowel strictures usually occur secondary to tuberculosis orCrohn’s disease. Malignant strictures associated with lymphomaare common, whereas carcinoma and sarcoma are rare

Bolus obstructionBolus obstruction in the small bowel may be caused by food, gallstones, trichobezoar, phytobezoar, stercoliths and worms

GallstonesThis type of obstruction tends to occur in the elderly secondaryto erosion of a large gallstone through the gall bladder into theduodenum. Classically, there is impaction about 60 cm proximalto the ileocaecal valve. The patient may have recurrent attacksas the obstruction is frequently incomplete . At laparotomy it may be possibleto crush the stone within the bowel lumen, after milking itproximally. If not, the intestine is opened and the gallstoneremoved.

FoodBolus obstruction may occur after partial or total gastrectomywhen unchewed articles can pass directly into the small bowel.Fruit and vegetables are particularly liable to cause obstruction.

Trychobezoars and phytobezoarsThese are firm masses of undigested hair balls and fruit/vegetablefibre . The former is due to persistent hair chewing orsucking, and may be associated with an underlying psychiatricabnormality. Predisposition to phytobezoars results from a highfibre intake, inadequate chewing, previous gastric surgery,hypochlorhydria and loss of the gastric pump mechanism.

WormsAscaris lumbricoides may cause low small bowel obstruction,particularly in children, the institutionalised and those near thetropics.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF INTESTINALOBSTRUCTIONDynamic obstructionThe diagnosis of dynamic intestinal obstruction is based on theclassic quartet of pain, distension, vomiting and absoluteconstipation. Obstruction may be classified clinically into twotypes:• small bowel obstruction – high or low;• large bowel obstruction

The nature of the presentation will also be influenced by whetherthe obstruction is:• acute;• chronic;• acute on chronic;• subacute.Acute obstruction usually occurs in small bowel obstruction, withsudden onset of severe colicky central abdominal pain, distensionand early vomiting and constipation

Chronic obstruction is usually seen in large bowel obstruction,with lower abdominal colic and absolute constipation followedby distension. Presentation will be further influenced by whether theobstruction is:• simple – in which the blood supply is intact;• strangulating/strangulated – in which there is direct interferenceto blood flow, usually by hernial rings or intraperitonealadhesions/bands.

The clinical features vary according to:• the location of the obstruction;• the age of the obstruction;• the underlying pathology;• the presence or absence of intestinal ischaemia.

PainPain is the first symptom encountered; it occurs suddenly and isusually severe. It is colicky in nature and is usually centred on theumbilicus (small bowel) or lower abdomen (large bowel). The development of severe pain is indicative of the presenceof strangulation. Pain may not be a significant feature in postoperative simple mechanical obstruction and does not usually occur in paralytic ileus.

VomitingThe more distal the obstruction, the longer the interval betweenthe onset of symptoms and the appearance of nausea and vomiting.As obstruction progresses the character of the vomitus altersfrom digested food to faeculent material, as a result of the presence of enteric bacterial overgrowth.

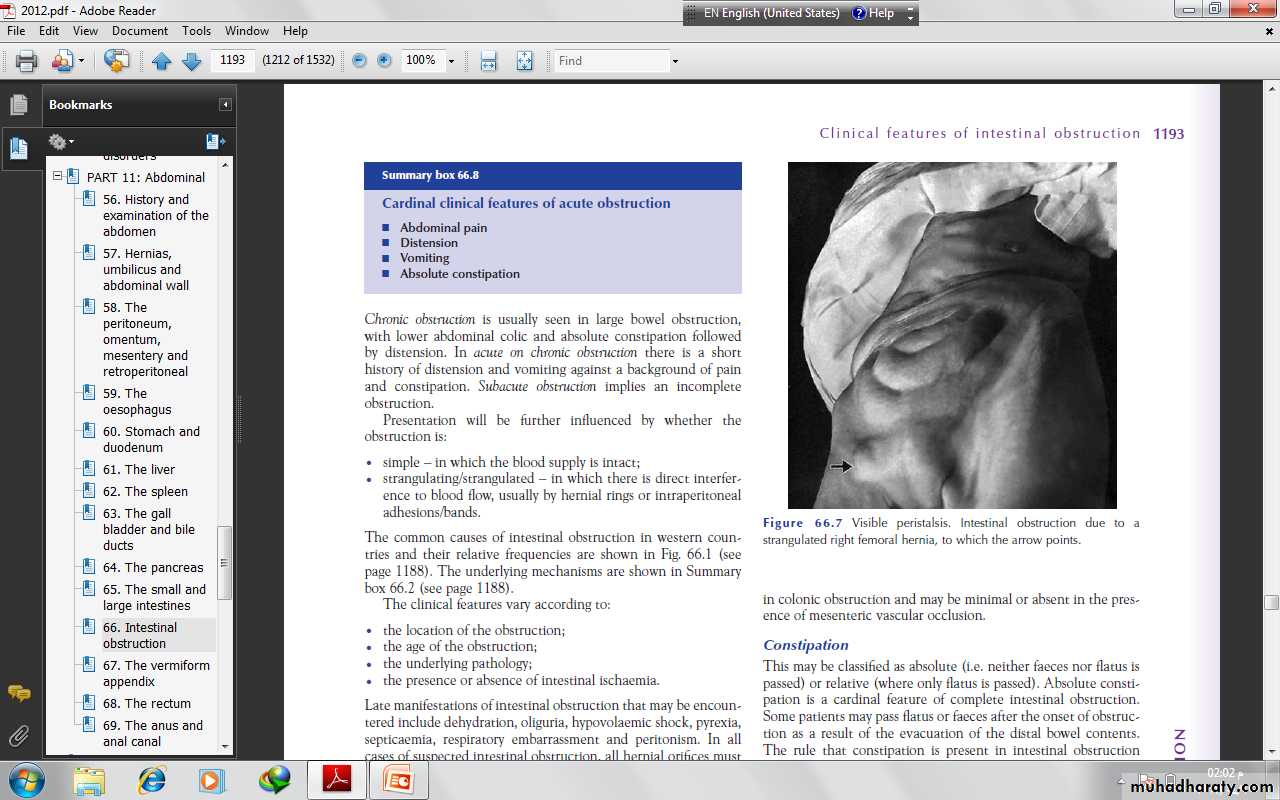

DistensionIn the small bowel the degree of distension is dependent on thesite of the obstruction and is greater the more distal the lesion.Visible peristalsis may be present . Distension is delayedin colonic obstruction and may be minimal or absent in the presence of mesenteric vascular occlusion.

ConstipationThis may be classified as absolute (i.e. neither faeces nor flatus ispassed) or relative (where only flatus is passed). Absolute constipation is a cardinal feature of complete intestinal obstruction.The rule that constipation is present in intestinal obstructiondoes not apply in:• Richter’s hernia;• gallstone ileus;• mesenteric vascular occlusion;• obstruction associated with pelvic abscess;• partial obstruction

Other manifestationsDehydrationDehydration is seen most commonly in small bowel obstructionbecause of repeated vomiting and fluid sequestration. It results indry skin and tongue, poor venous filling and sunken eyes witholiguria. The blood urea level and haematocrit rise, giving a secondary polycythaemia.HypokalaemiaHypokalaemia is not a common feature in simple mechanicalobstruction. An increase in serum potassium, amylase or lactatedehydrogenase may be associated with the presence of strangulation, as may leucocytosis or leucopenia.

PyrexiaPyrexia in the presence of obstruction may indicate:• the onset of ischaemia;• intestinal perforation;• inflammation associated with the obstructing disease.Hypothermia indicates septicaemic shock.Abdominal tendernessLocalised tenderness indicates pending or established ischaemia.The development of peritonism or peritonitis indicates overtinfarction and/or perforation.

Clinical features of strangulation■ Constant pain■ Tenderness with rigidity■ ShockIn addition to the features above, it should be noted that:• the presence of shock indicates underlying ischaemia;• in impending strangulation, pain is never completely absent;• symptoms usually commence suddenly and recur regularly;• the presence and character of any local tenderness are of greatsignificance

Clinical features of intussusceptionThe classical presentation of intussusception is with episodes ofscreaming and drawing up of the legs in a previously well maleinfant. Vomiting may or may not occur. Initially, thepassage of stool may be normal, whereas, later, blood and mucusare evacuated – the ‘redcurrant jelly’ stool. the abdomen is not initially distended; a lump thathardens on palpation may be discerned but this is present in only60% of cases . There may be an associated feeling ofemptiness in the right iliac fossa (the sign of Dance). On rectalexamination, blood-stained mucus may be found on the finger.Occasionally, in extensive ileocolic or colocolic intussusception,the apex may be palpable or even protrude from the anus.Unrelieved, progressive dehydration and abdominal distensionfrom small bowel obstruction will occur, followed by peritonitissecondary to gangrene. Rarely, natural cure may occur as aresult of release of the intussusception.

Differential diagnosisAcute gastroenteritisHenoch–Schِenlein purpuraRectal prolapse

Clinical features of volvulus Sigmoid volvulusThe symptoms are of large bowel obstruction, which may initiallybe intermittent followed by the passage of large quantities offlatus and faeces.Abdominal distension is an early and progressive sign, which maybe associated with hiccough and retching; vomiting occurs late.Constipation is absolute.IMAGINGErect abdominal films are no longer routinely obtained and theradiological diagnosis is based on a supine abdominal film. An erect film may subsequently be requested when furtherdoubt exists.When distended with gas, the jejunum, ileum, caecum andremaining colon have a characteristic appearance in adults andolder children that allows them to be distinguished radiologically.

In intestinal obstruction, fluid levels appear later than gas shadowsas it takes time for gas and fluid to separate .These are most prominent on an erect film. In adults, two inconstant fluid levels – one at the duodenal cap and the other in the terminal ileum – may be regarded as normal.In infants (less than 1 year old), a few fluid levels in the small bowel may be physiological.

A barium follow-through is contraindicatedin the presence of acute obstruction and may belife-threatening.Impacted foreign bodies may be seen on abdominal radiographs.In gallstone ileus, gas may be seen in the biliary tree, withthe stone visible

Imaging in intussusceptionA soft tissue opacity is often visible in children. A bariumenema may be used to diagnose the presence of an ileocolic intussusception(the claw sign) . An abdominal ultrasound scan has ahigh diagnostic sensitivity in children, demonstrating the typicaldoughnut appearance of concentric rings in transverse section. Acomputerised tomography (CT) scan is also useful in equivocalcases.

Imaging in volvulusIn caecal volvulus, radiography may reveal a gas-filled ileum andoccasionally a distended caecum. A barium enema may be usedto confirm the diagnosis, with an absence of barium in thecaecum and a bird beak deformity.In sigmoid volvulus, a plain radiograph shows massive colonicdistension. The classic appearance is of a dilated loop of bowel.

TREATMENT OF ACUTE INTESTINALOBSTRUCTIONThere are three main measures used to treat acute intestinalobstruction■ Gastrointestinal drainage■ Fluid and electrolyte replacement■ Relief of obstruction , Surgical treatment is necessary for most cases of intestinal obstruction but should be delayed until resuscitation is complete, provided there is no sign of strangulation or evidence of closed-loop obstructionThe first two steps are always necessary before attempting the surgical relief of obstruction and are the mainstay of postoperativemanagement

Supportive managementNasogastric decompression is achieved by the passage of a nasogasteric tube. The tubes are normally placed on free drainage with 4-hourly aspiration but may be placed on continuous or intermittent suction. As well as facilitatingdecompression proximal to the obstruction, they also reducethe risk of subsequent aspiration during induction of anaesthesiaand post-extubation.The basic biochemical abnormality in intestinal obstruction issodium and water loss, and therefore the appropriate replacementis Hartmann’s solution or normal saline.

Antibiotics are not mandatory but many clinicians initiatebroad-spectrum antibiotics early in therapy because of bacterialovergrowth. Antibiotic therapy is mandatory for all patientsundergoing small or large bowel resection.

Surgical treatmentThe timing of surgical intervention is dependent on the clinicalpicture. There are several indications for early surgical intervention

The classic clinical advice that ‘the sun should not both rise andset’ on a case of unrelieved acute intestinal obstruction is soundand should be followed unless there are positive reasons for delay.Such cases may include obstruction secondary to adhesions whenthere is no pain or tenderness, despite continued radiologicalevidence of obstruction. In these circumstances, conservativemanagement may be continued for up to 72 hours in the hope ofspontaneous resolution.If the site of obstruction is unknown, adequate exposure isbest achieved by a midline incision. Assessment is directed to:• the site of obstruction;• the nature of the obstruction;• the viability of the gut.

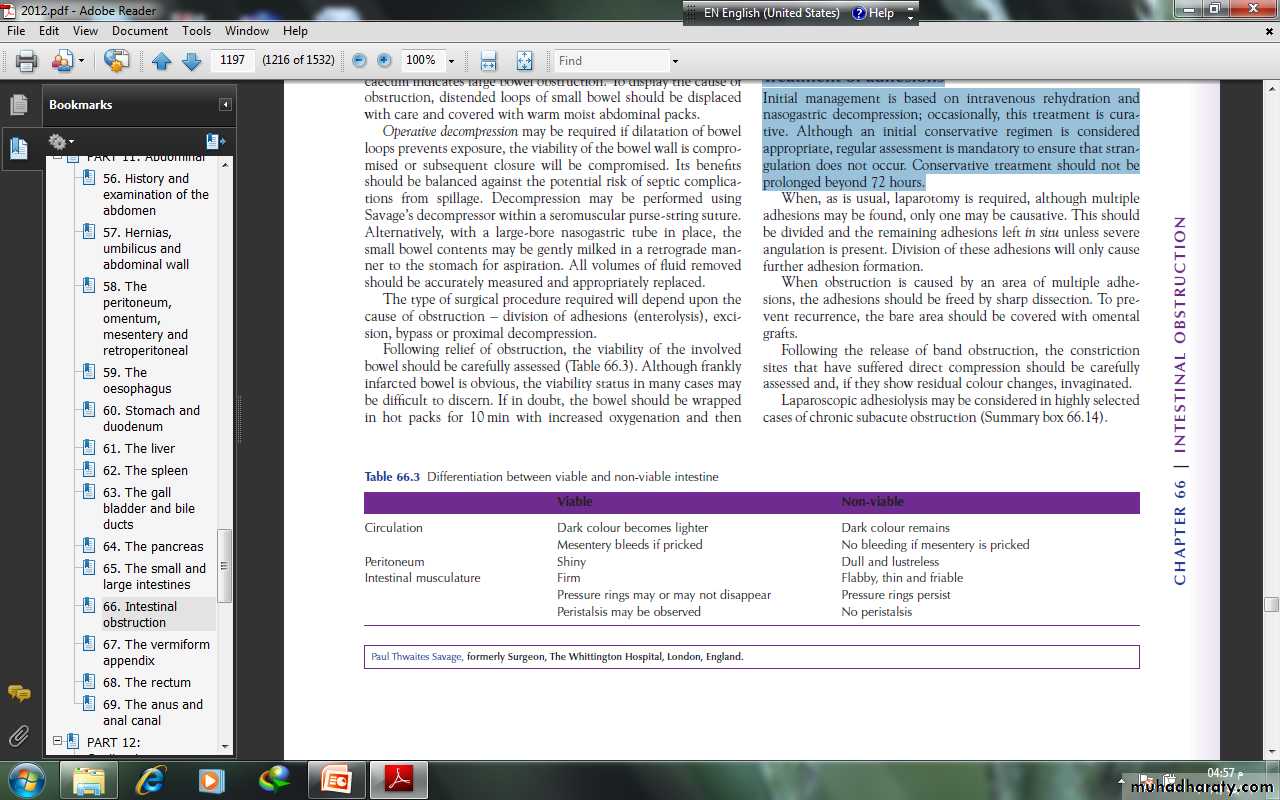

Treatment of adhesionsInitial management is based on intravenous rehydration andnasogastric decompression; occasionally, this treatment is curative.Although an initial conservative regimen is consideredappropriate, regular assessment is mandatory to ensure that strangulation does not occur. Conservative treatment should not be prolonged beyond 72 hours.

Treatment of intussusceptionIn the infant with ileocolic intussusception, after resuscitationwith intravenous fluids, broad-spectrum antibiotics and nasogastricdrainage, non-operative reduction can be attempted usingan air or barium enema . Successful reduction can only be accepted if there is free reflux of air or barium into the small bowel, together with resolution of symptoms and signs in the patient. Non-operative reduction is contraindicatedif there are signs of peritonitis or perforation, there is aknown pathological lead point or in the presence of profoundshock. Surgery is required when radiological reduction has failed or is contraindicated.

TREATMENT OF ACUTE LARGE BOWELOBSTRUCTIONLarge bowel obstruction is usually caused by an underlying carcinoma or occasionally diverticular disease, and presents in anacute or chronic form. The condition of pseudo-obstructionshould always be considered and excluded by a limited contraststudy or a CT air scan to confirm organic obstruction.

In the absence of senior clinical staff it is safest to bring theproximal colon to the surface as a colostomy. When possible thedistal bowel should be brought out at the same time (Paul–Mikulicz procedure) to facilitate subsequent extraperitonealclosure. In the majority of cases, the distal bowel will not reachand is closed and returned to the abdomen (Hartmann’s procedure).A second-stage colorectal anastomosis can be plannedwhen the patient is fit.If an anastomosis is to be considered using the proximal colon,in the presence of obstruction, it must be decompressed andcleaned by an on-table colonic lavage. Nevertheless, the subsequentanastomosis should still be protected with a coveringstoma.

Treatment of caecal volvulusAt operation the volvulus should be reduced. Sometimes, thiscan only be achieved after decompression of the caecum using aneedle. Further management consists of fixation of the caecum tothe right iliac fossa (caecopexy) and/or a caecostomy. If thecaecum is ischaemic or gangrenous, a right hemicolectomyshould be performed.

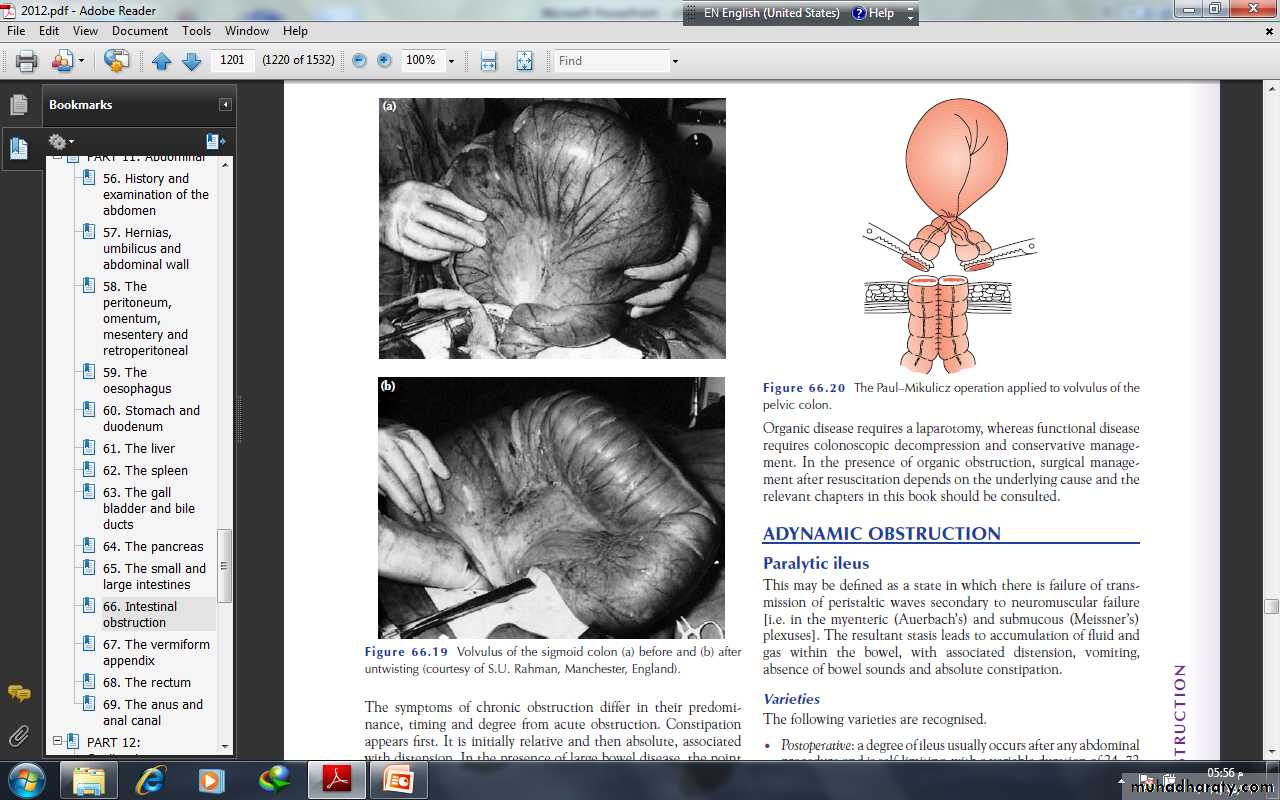

Treatment of sigmoid volvulusFlexible sigmoidoscopy or rigid sigmoidoscopy and insertion of aflatus tube should be carried out to allow deflation of the gut.Failure results in an early laparotomy, with untwisting of theloop and per anum decompression. When the bowelis viable, fixation of the sigmoid colon to the posterior abdominalwall may be a safer manoeuvre in inexperienced hands. Resectionis preferable if it can be achieved safely. A Paul–Mikulicz procedureis useful, particularly if there is suspicion of impendinggangrene

an alternative procedure is a sigmoid colectomyand, when anastomosis is considered unwise, a Hartmann’sprocedure with subsequent reanastomosis can be carried out

ADYNAMIC OBSTRUCTIONParalytic ileusThis may be defined as a state in which there is failure of transmission of peristaltic waves secondary to neuromuscular failure [i.e. in the myenteric (Auerbach’s) and submucous (Meissner’s) plexuses]. The resultant stasis leads to accumulation of fluid and gas within the bowel, with associated distension, vomiting, absence of bowel sounds and absolute constipation.

The following varieties are recognised.• Postoperative: a degree of ileus usually occurs after any abdominal procedure and is self-limiting, with a variable duration of 24–72 hours.• Infection: intra-abdominal sepsis may give rise to localised orgeneralised ileus.• Reflex ileus: this may occur following fractures of the spine orribs, retroperitoneal haemorrhage.• Metabolic: uraemia and hypokalaemia are the most commoncontributory factors

Clinical featuresParalytic ileus takes on a clinical significance if, 72 hours afterlaparotomy:• there has been no return of bowel sounds on auscultation;• there has been no passage of flatus

Abdominal distension becomes more marked and tympanitic.Pain is not a feature. In the absence of gastric aspiration, effortlessvomiting may occur. Radiologically, the abdomen shows gasfilledloops of intestine with multiple fluid levels.

ManagementThe treatment is prevention, with the use of nasogastricsuction and restriction of oral intake until bowel sounds and thepassage of flatus return. Electrolyte balance must be maintained.The use of an enhanced recovery programme with early introduction of fluids and solids is becoming increasingly popular

Specific treatment is directed towards the cause, but the followinggeneral principles apply:• The primary cause must be removed.• Gastrointestinal distension must be relieved by decompression.• Close attention to fluid and electrolyte balance is essential.• There is no place for the routine use of peristaltic stimulants.Rarely, in resistant cases, medical therapy with an adrenergicblocking agent in association with cholinergic stimulation, e.g.neostigmine , may be used, provided that an intraperitoneal cause has been excluded.• If paralytic ileus is prolonged and threatens life, a laparotomyshould be considered to exclude a hidden cause and facilitatebowel decompression.

Pseudo-obstructionThis condition describes an obstruction, usually of the colon, thatoccurs in the absence of a mechanical cause or acute intraabdominal disease. It is associated with a variety of syndromes in which there is an underlying neuropathy and/or myopathy and a range of other factors

Factors associated with pseudo-obstructionIdiopathic■ MetabolicDiabetes: intermittent porphyriaAcute hypokalaemiaUraemiaMyxodoema■ Severe trauma (especially to the lumbar spine and pelvis)■ ShockBurnsMyocardial infarctionStrokeSepticaemia■ Retroperitoneal irritationBloodUrineEnzymes (pancreatitis)Tumour■ DrugsTricyclic antidepressantsPhenothiazinesLaxatives■ Secondary gastrointestinal involvementSclerodermaChagas’ disease

Colonic pseudo-obstructionThis may occur in an acute or a chronic form. The former, alsoknown as Ogilvie’s syndrome, presents as acute large bowelobstruction. Abdominal radiographs show evidence of colonicobstruction, with marked caecal distension being a commonfeature. Indeed, caecal perforation is a well-recognised complication.The absence of a mechanical cause requires urgent confirmationby colonoscopy or a single-contrast water-soluble bariumenema or CT. Once confirmed, pseudo-obstruction should betreated by colonoscopic decompression. When colonoscopy fails or is unavailable, a tube caecostomy may be required

Acute mesenteric ischaemiaMesenteric vascular disease may be classified as acute intestinalischaemia – with or without occlusion – venous, chronic arterial,central or peripheral. The superior mesenteric vessels are thevisceral vessels most likely to be affected by embolisation orthrombosis, with the former being most common.

Possible sources for the embolisation of the SMA include a leftatrium associated with fibrillation, a mural myocardial infarction,an atheromatous plaque from an aortic aneurysmPrimary thrombosis is associated with atherosclerosis andthromboangitis obliterans. Primary thrombosis of the superiormesenteric veins may occur in association with factor V Leiden,portal hypertension, portal pyaemia and sickle cell disease

Clinical featuresThe most important clue to an early diagnosis of acute mesentericischaemia is the sudden onset of severe abdominal pain in apatient with atrial fibrillation or atherosclerosis. The pain is typically central and out of all proportion to physical findings

Persistent vomiting and defaecation occur early, with the subsequent passage of altered blood. Hypovolaemic shock rapidlyensues. Abdominal tenderness may be mild initially with rigiditybeing a late feature .

Investigation will usually reveal a profound neutrophil leucocytosiswith an absence of gas in the thickened small intestine onabdominal radiographs. The presence of gas bubbles in themesenteric veins is rare but pathognomonic

Treatment : In conjunction with full resuscitation, embolectomy via the ileocolic artery or revascularisation of the SMA