Upper GI Bleeding&Portal Hypertension

Dr. Ali JafferUpper GI surgeon

Background

Bleeding derived from a source proximal to the ligament of Treitz.Bleeding from the upper GI tract is approximately 4 times more common than bleeding from the lower GI tract.

Mortality rates from UGIB are 6-10% overall.

Comorbid diseases increase the death rate.

Rebleeding and continued bleeding is a significant factor of mortality.

Aetiology

Causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.Condition %

Ulcers 60

Oesophageal 6

Gastric 21

Duodenal 33

Erosions 26

Oesophageal 13

Gastric 9

Duodenal 4

Mallory–Weiss tear 4

Oesophageal varices 4

Tumour 0.5

Vascular lesions, e.g. Dieulafoy’s disease 0.5

Others 5

Prognosis

The following risk factors are associated with an increased mortality, recurrent bleeding, the need for endoscopic hemostasis, or surgery :

1. Age older than 60 years

2. Severe comorbidity

3. Active bleeding (eg, witnessed hematemesis, red blood per nasogastric tube, fresh blood per rectum)

4. Hypotension

5. Red blood cell transfusion greater than or equal to 6 units

6. Inpatient at time of bleed

7. Severe coagulopathy

Patients who present in hemorrhagic shock have a mortality rate of up to 30%

History

Important informationpotential comorbid conditions,

medication history, and potential toxic exposures

severity, timing, duration, and volume of the bleeding

Hematemesis

Melena

Hematochezia

Syncope

Dyspepsia

Epigastric pain

Heartburn

Diffuse abdominal pain

Dysphagia

Weight loss

Jaundice

Physical Examination

The goal; to evaluate for shock and blood loss.

Assessing the patient for hemodynamic instability and clinical signs of poor perfusion is important early in the initial evaluation to properly triage patients with massive hemorrhage.

Worrisome clinical signs and symptoms of hemodynamic compromise include

Tachycardia of more than 100 beats per minute (bpm)Systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg,

Cool extremities, syncope, and other obvious signs of shock,

Ongoing brisk hematemesis,

The occurrence of maroon or bright-red stools, which requires rapid blood transfusion.

Pulse and blood pressure should be checked with the patient in supine and upright positions to note the effect of blood loss. Significant changes in vital signs with postural changes indicate an acute blood loss of approximately 20% or more of the blood volume.

Signs of chronic liver disease should be noted, including spider angiomata, gynecomastia, splenomegaly, ascites, ....etc.

nodular liver, an abdominal mass, and enlarged and firm lymph nodes.

Work upAssessment of hemorrhagic shock

patients who present in hemorrhagic shock have a mortality rate of up to 30%

Estimated Fluid and Blood Losses in Shock

Class 1

Class 2Class 3

Class 4Blood Loss, mL

Up to 750750-1500

1500-2000

>2000

Blood Loss,% blood volume

Up to 15%

15-30%

30-40%

>40%

Pulse Rate, bpm

< 100

>100

>120

>140

Blood Pressure

Normal

Normal

Decreased

Decreased

Respiratory Rate

Normal or Increased

Decreased

Decreased

Decreased

Urine Output, mL/h

>35

30-40

20-30

14-20

CNS/Mental Status

Slightly

anxious

Mildly

anxious

Anxious,

confused

Confused,

lethargic

Work up

Hemoglobin Value and Type and Crossmatch Blood

CBC should be checked frequently (4-6h) during the first day.

The patient should be crossmatched for 2-6 units, based on the rate of active bleeding.

Patients with significant comorbid conditions (eg, advanced cardiovascular disease) should receive blood transfusions to maintain myocardial oxygen delivery to avoid myocardial ischemia.

The more units required, the higher the mortality rate.

Operative intervention is indicated once the blood transfusion number reaches more than 5 units.

Coagulation Profile

The patient's prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratio (INR) should be checked to document the presence of coagulopathy. The coagulopathy may be consumptive and associated with a thrombocytopeniaWork up

EndoscopyDiagnostic&theraputic

Endoscopy should be performed immediately after endotracheal intubation (if indicated), hemodynamic stabilization, and adequate monitoring in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting have been achieved.

Chest Radiography

Computed Tomography Scanning

Liver disease for cirrhosis, pancreatitis with pseudocyst and hemorrhage, aortoenteric fistula, and other unusual causes of upper GI hemorrhage.

Nuclear Medicine Scanning

Nuclear medicine scans may be useful in determining the area of active hemorrhage.

Angiography

Angiography may be useful if bleeding persists and endoscopy fails to identify a bleeding site.

Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) should be considered for all patients with a known source of arterial UGIB that does not respond to endoscopic management, with active bleeding and a negative endoscopy.

Nasogastric Lavage

PPIs

Treatment of underlying cause

Portal Hypertension

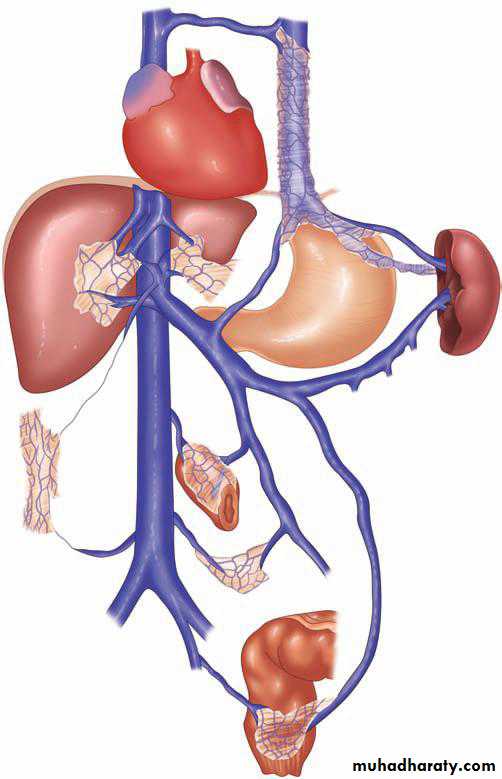

The portal venous system contributes approximately 75% of the blood and 72% of the oxygen supplied to the liver.

In the average adult, 1000 to 1500 mL/min of portal venous blood is supplied to the liver.

The normal portal venous pressure is 5 to 10 mmHg, and at this pressure, very little blood is shunted from the portal venous system into the systemic circulation.

As portal venous pressure increases, the collateral communications with the systemic circulation dilate, and a large amount of blood may be shunted around the liver and into the systemic circulation.

Lower oesophagus; Left gastric veins (portal system) -> lower branches of oesophageal veins (systemic veins)

Upper part of anal canal; Superior rectal veins (portal) -> inferior and middle rectal veins (systemic)

Umbilicus; Paraumbilical veins (portal) -> epigastric veins (systemic)

Area of the liver; Intraparenchymal branches of right division of portal vein (portal) -> retroperitoneal veins (systemic)

Hepatic and splenic flexures; Omental and colonic veins (portal) -> retroperitoneal veins (systemic)

Aetiology of portal hypertension

PresinusoidalSinistral/extrahepatic

Splenic vein thrombosis

Splenomegaly

Splenic arteriovenous fistula

Intrahepatic

Schistosomiasis

Congenital hepatic fibrosis

Nodular regenerative hyperplasia

Idiopathic portal fibrosis

Myeloproliferative disorder

Sarcoid

Graft-versus-host disease

Sinusoidal

Intrahepatic

Cirrhosis

Viral infection

Alcohol abuse

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Autoimmune hepatitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Metabolic abnormality

Postsinusoidal

Intrahepatic

Vascular occlusive disease

Posthepatic

Budd-Chiari syndrome

Congestive heart failure

Inferior vena caval web

Constrictive pericarditis

Portal hypertension per se produces no symptoms, it is usually diagnosed following presentation with decompensated chronic liver disease and

encephalopathy, ascites or variceal bleeding.

Management of bleeding varices

General resuscitationMedical emergency

ICU

Two large pore peripheral canulae

Resuscitation, avoid fluid overload (why?)

Correction of coagulopathy; Vit K(10mg) i.v., tranexamic acid (1g i.v), FFP, platelet transfusion

Activation of major blood transfusion protocol

Drug therapy (terlipressin) splanchnic vasocinstriction

Prophylactic antibiotics

Endoscopy ; 50% PHT non variceal bleeding

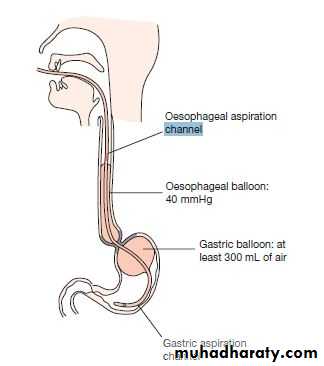

Sengstaken-Blakemore, temporary control; Once inserted, the gastric balloon is inflated with 300 mL of air and retracted to the gastric fundus, where the varices at the oesophagogastric junction are tamponaded by the subsequent inflation of the oesophageal balloon to a pressure of 40 mmHg. The balloons should be temporarily deflated after 12 hours to prevent pressure necrosis of the oesophagus.

Management of bleeding varices

Endoscopic treatment of varices

Endoscopic band ligation

Endoscopic sclerotherapy

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunts

the main treatment of variceal haemorrhage that has not responded to drug treatment and endoscopic therapy.Complications:

Liver capsule perfuration…. Intraperitoneal hemorrhage

Occlusion resulting in further variceal bleeding

Post shunt encephalopathy 40% of cases

TIPS stenosis (50% after one year)

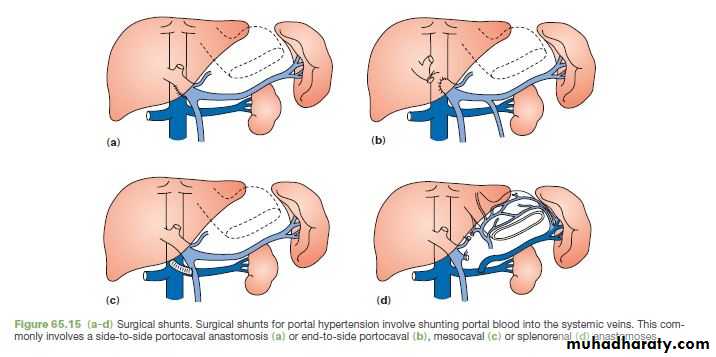

Surgical shunts for variceal haemorrhage

Surgical shunts are an effective method of preventing rebleeding from oesophageal or gastric varices, as they reduce the pressure in the portal circulation by diverting the blood into the low-pressure systemic circulation.

Long-term β-blocker therapy and chronic sclerotherapy or banding are the main alternatives.

Liver transplantation is the only therapy that will treat both portal hypertension and the underlying liver disease.

Ascites

Portal vein thrombosis is a common predisposing factor to the development of ascites in chronic liver disease. In patients without evidence of liver disease, malignancy is a common causeAspiration of the peritoneal fluid allows the measurement of protein content to determine whether the fluid is an exudate or transudate, an amylase estimation to exclude pancreatic ascites.

Cytology will determine the presence of malignant cells

Microscopy and culture will exclude primary bacterial and tuberculous peritonitis.

Treatment of ascites in chronic liver disease

Salt restrictionDiuretics

Abdominal paracentesis

TIPSS

Liver transplantation