1

Thoracic Trauma

Introduction

Early deaths after thoracic trauma are caused by hypoxemia, hypovolaemia and

tamponade. The first steps in treating these patients should be to diagnose and treat

these problems as early as possible because they may be readily corrected. Young

patients have a large physiological reserve and serious injury may be overlooked until

this reserve is used up; then the situation is critical and may be irretrievable. The best

approach is to maintain a high index of suspicion and suspect the worst if life-

threatening conditions are to be anticipated and treated.

The basic principles of resuscitation are securing the airway and restoring the

circulating volume. Blood and secretions are removed from the oropharynx by suction.

If the patient is unable to maintain his or her airway then an oropharyngeal airway

followed by tracheal intubation (once a cervical spine injury is excluded) may be

necessary.

A thorough inspection of the chest wall includes noting the frequency and pattern of

breathing, external evidence of trauma and structural defects of the thorax.

Palpation will detect surgical emphysema, paradoxical movement and a stove-in chest.

Auscultation and percussion should reveal the existence of a pneumothorax (there is

decreased movement on the affected side with a hyperresonant percussion note, reduced

breath sounds in the axilla and shift of the trachea to the opposite side) which requires

emergency drainage.

Patients with injuries close to the trachea or esophagus should undergo endoscopy,

and patients with radiological clues suggestive of great vessels injury should undergo

arteriography.

Once the patient has been stabilized then radiographs of the chest should be taken

and further treatment decided on the basis of the patient’s condition and the

radiographic result.

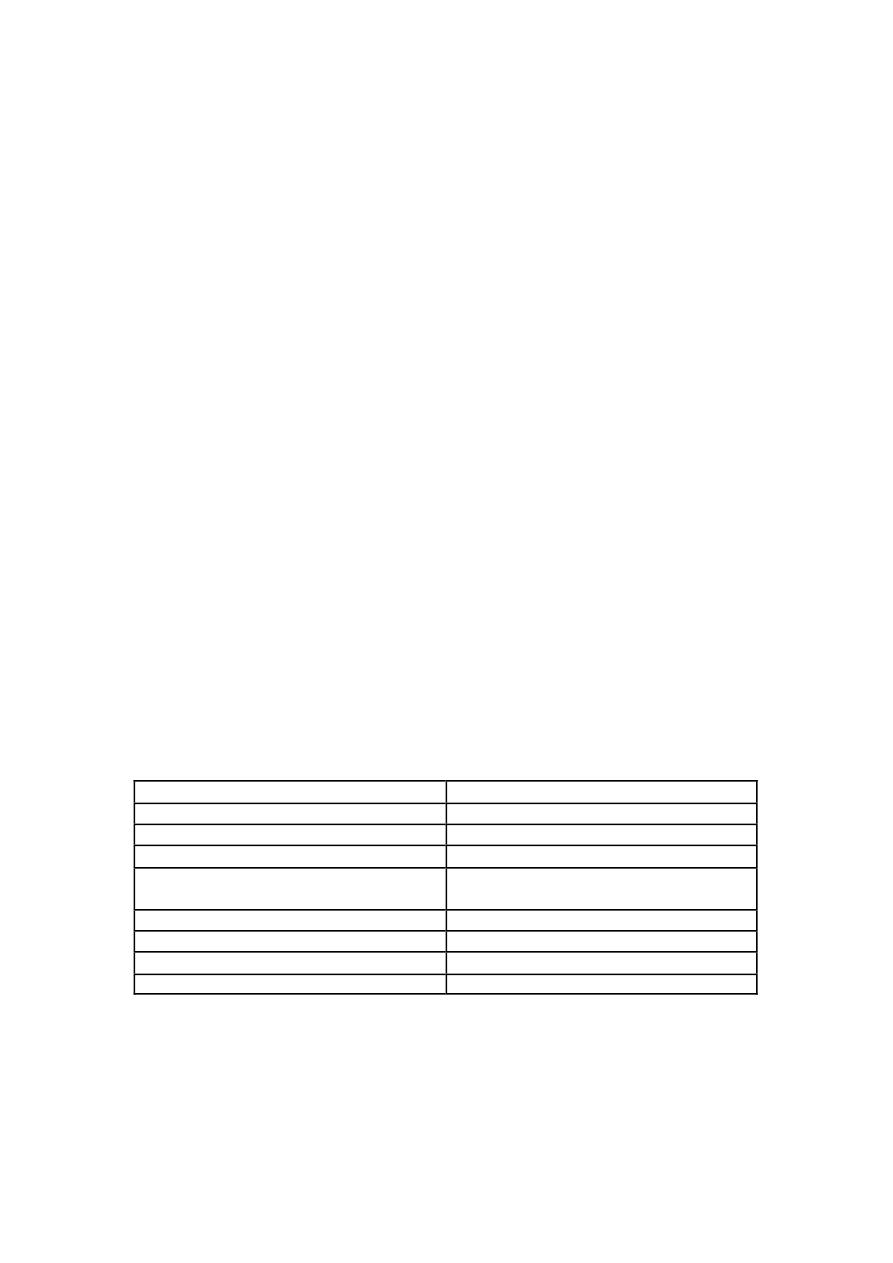

Table 1: Potentially acutely lethal injuries of the chest and their management

Tension pneumothorax

Tube thoracostomy

Massive intrathoracic hemorrhage

Tube thoracostomy, operative repair

Cardiac tamponade

Pericardocentesis, operative repair

Deceleration aortic injury

Operative repair

Massive flail chest with pulmonary

contusion

Intubation, pain control, fluid restriction

Upper and lower airway obstruction

Intubation, airway, bronchoscopy

Tracheobronchial rupture

Bronchoscopy, operative repair

Diaphragmatic rupture

Operative repair

Esophageal perforation

Operative repair

Blunt Trauma of the Chest

2

Rib Fractures

A simple rib fracture may be serious in elderly people or in those with chronic lung

disease who have little pulmonary reserve. Uncomplicated fractures require sufficient

analgesia to encourage a normal respiratory pattern and effective coughing. Oral

analgesia may suffice but intercostal nerve blockade with local anesthesia may be very

helpful. Chest strapping or bed rest is no longer advised and early ambulation with

vigorous physiotherapy (and oral antibiotics if necessary) is encouraged. A chest

radiograph is always taken to exclude an underlying pneumothorax. It is useful to

confirm the skeletal injuries but routine chest radiography may miss rib fractures.

However, once a pneumothorax and major skeletal injuries are excluded, the

management is the same — the local control of chest pain.

.

Flail chest

This occurs when several adjacent ribs (more than four) are fractured in two

places either on one side of the chest or either side of the sternum. The flail segment

moves paradoxically. The net result is poor oxygenation from injury to the

underlying lung parenchyma and paradoxical movement of the flail segment. The

underlying lung injury with loss of alveolar function may result in deoxygenated

blood passing into the systemic circulation. This creates a right-to-left shunt and

prevents full saturation of arterial blood. In the absence of any other injuries and if

the segment is small and not embarrassing respiration, the patient may be nursed on

a high-dependency unit with regular blood gas analysis and good analgesia until the

flail segment stabilizes. In the more severe case, endotracheal intubation is required

with positive pressure ventilation for up to 3 weeks, until the fractures become less

mobile.

Crystalloid solutions should be restricted to less than 1000 ml daily. If volume

expansion is needed, colloid solutions should be given.

Indications for Endotracheal intubation are:

• Respiratory rate of 30-40/min.

• Arterial PO2 of 60 torr or less (on face mask O2 of 60%).

• Arterial PCO2 of 50 torr or more.

• Presence of associated injuries.

• Pre-existing chronic lung disease.

• Depressed consciousness.

• Shallow respirations.

When the lung is healed, the patient may be extubated, even if flailing persists.

Thoracotomy with fracture fixation is occasionally appropriate if:

1) there is an underlying lung injury to be treated at the same time.

2) Intubated patients with no possibility being weaned from the ventilator because

of large unstable flail segment.

.

Fractures of the sternum

3

The injury is very painful even in the mild cases where only the external plate of the

sternum is fractured. However, there is a real risk of underlying myocardial damage

(myocardial contusion) and lung damage (contusion), the patient should be observed in

hospital with constant electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring, analgesia and serial

cardiac enzymes.

The step deformity can be confirmed by lateral or oblique x-rays. Rupture of the

aorta and associated cervical spine injuries also need to be excluded. Most cases need

no specific treatment but paradoxical movement or instability of the chest may need

more active management.

Surgery is indicated for persistent pain and cosmesis.

.

Pleura.

If the visceral pleura is breached (most commonly by a rib fracture), pneumothorax

follows. Generation of positive pressure in the airways by coughing, straining, groaning

or positive pressure ventilation will result in tension pneumothorax. The pleural space

may also fill with blood as a result of injury anywhere in its vicinity. Remember that an

erect chest radiograph is the only sure way to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of

pneumothorax and hemothorax and should be obtained if at all possible.

*

Traumatic pneumothorax.

Blunt trauma to the chest wall may result in a lung laceration from a rib fracture. All

traumatic pneumothoraces require drainage through an underwater seal drain. If a

tension pneumothorax is suspected on clinical grounds, treatment is necessary before

radiographs can be taken. A chest tube or (if not available) wide bore needle introduced

into the affected hemithorax will release any air under tension and is life saving. A

second drain may be introduced basally to drain blood.

.

*

Traumatic hemothorax.

Drainage is essential because re-expansion of the lacerated lung compresses the torn

vessels and reduces further blood loss. Drainage will also allow the mediastinal

structures to return to the midline and relieve compression of the contralateral lung. If

left undrained, a dense fibrothorax will result with its morbid consequences i.e. trapped

lung syndrome, with the possibility of an added empyema; for that reason, clotted

hemothorax regarded as an indication for elective thoracotomy.

Lung parenchyma

After the chest wall, the lung is the most commonly injured intrathoracic organ,

manifestations of lung injury are pneumothorax, hemothorax, pulmonary contusion,

pulmonary hematoma, systemic air emboli, and ARDS.

The underlying lung is often injured in moderate-to-severe blunt thoracic trauma and

the area of contusion may be extensive. This usually resolves but lacerations with

persistent air leak may require exploration by thoracotomy. It is important to prevent

infection of the underlying lung by early mobilization with antibiotic cover, and to

prevent development of pulmonary edema by crystalloid fluid restriction.

Major airways

4

Injuries to major bronchi are infrequently seen as the patient rarely survives the insult

leading to major airway disruption. Injuries may be secondary to penetrating, blunt, or

iatrogenic trauma. There is usually a combination of surgical emphysema, hemoptysis,

pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax.

Symptoms usually develop immediately after penetrating trauma and there may be

some delay for up to one week in blunt trauma before atelectasis and pneumonia prompt

a detailed evaluation by bronchoscopy or bronchography.

Clinical clues suggestive of bronchial injury include:

• Unusually large and persistent air leak.

• Need for a second or third chest tube

• Incomplete expansion of a pneumothorax despite functioning chest tubes.

• Inability to keep lungs expanded.

• Refractory or recurrent lobar or whole lung atelectasis.

• CXR showing a pneumothorax with downward displacement of the hilum of

the lung.

Injury to the trachea requires considerable force and consequently less than a quarter

of patients survive to reach hospital. There is hoarseness, dyspnoea and surgical

emphysema.

Bronchoscopy or bronchography will be required to confirm the diagnosis. The exact

pattern of signs will depend on the site of the injury and whether or not the pleura has

been breached. The treatment is exploration and repair if possible.

The proximal one half to two thirds of the trachea is best approached via a low cervical

collar incision, whereas the distal third of the trachea, carina, and proximal right and

left mainstem bronchi should be approached through a right thoracotomy. Resection of

lung should be avoided.

Great Vesseles

The thoracic great vessels consist of the aorta and its major intrathoracic branches,

the pulmonary arteries and veins, the vena cavae, and the azygos vein. By far the most

lethal of these is the descending aortic injury , the site of the injury is the medial

descending aorta at the ligamentum arteriosum. Aortic transection is usually the result

of a major deceleration injury (road traffic accident or a fall from height) and the patient

often has other injuries.

In the last decade or so, the four most dramatic changes in the management of these

patients have been non operative management, delay of definitive treatment, use of

endovascular stenting for repair, and the increasing use of left sided bypass via

centrifugal pumps in the operating room. The open surgical approach is via a fourth

interspace left posterolateral thoracotomy.

.

Diaphragm

Blunt diaphragmatic rupture occurs mainly from high speed motor vehicle crashes.

This injury can be classified into three clinical phases, acute, latent, and obstructive

phases. The acute phase begins with the original trauma and ends with the apparent

recovery from other injuries. In the latent or interval phase symptoms are variable and

non specific and are suggestive of other disorders such as peptic ulcer, gall bladder

disorders, partial bowel obstruction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The obstructive phase may occur at any time.

5

Plain chest films are the initial screening tests of choice.

The surgical approach to repair acute diaphragmatic injury depends on mechanism of

injury, condition of the patient and the time of presentation.

In the acute phase the laparotomy approach is preferred, while thoracic approach is

preferred in the latent and obstructive phases because of possible adhesions between

herniated abdominal viscera and thoracic organs, however, thoracotomy approach

should be used for all right sided diaphragmatic defects regardless of the timing after

initial injury.

Management of blunt chest trauma (in general)

Most chest injuries where the heart is not injured are managed conservatively with

underwater seal drainage, oxygen and physiotherapy to help the patient to expectorate

while the underlying lung parenchyma heals. In about 10 per cent of cases a

thoracotomy is required.

The indications for tube thoracostomy:

It can be a life saving procedure and/or monitoring system for cases with continued

blood loss, and the general indications are:

1) Pneumothorax

2) Tension pneumothorax

3) Hemothorax

4) Penetrating wound below the nipples and without hemopneumothorax, for

whom an exploratory laparatomy is planned.

5) ARDS patients on ventilator with high PEEP (bilateral).

6) Extensive subcutaneous emphysema (bilateral).

The indications for thoracotomy following blunt thoracic trauma are the

following:

A) urgent

• For those rapidly deteriorating because of exsanguinating hemorrhage or from

tamponade.

B) emergent

1) drainage of more than 1500 ml of blood during time of chest tube insertion.

2) continued brisk bleeding (>100 mI/15 minutes).

3) continued bleeding of >200 ml/hour for 3 or more hours.

4) rupture of the bronchus, aorta, esophagus.

5) cardiac tamponade.

C) elective

1) Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia.

2) Traumatic false aneurysm.

3) Delayed post-traumatic squelae of penetrating cardiac injuries (valvular and

septal defects).

4) Stenosis of trachea or main stem bronchus.

5) Evacuation of clotted hemothorax.

Penetrating Injury of the Chest

6

In some aspects, penetrating thoracic injury is simpler to be dealt with than blunt

trauma because the wound is visible and the structures at risk can be quickly assessed.

A defect in the chest wall through to the pleura is a ‘sucking wound’. The underlying

lung collapses and air moves in and out of the thorax with each breath. Emergency

treatment involves sealing the wound and intercostal drainage. Definitive treatment

may then follow. It is important to establish the path or track of bullet and stab wounds

in the chest as there may be damage to the heart, great vessels, and the diaphragm and

abdominal viscera in addition to the lung injury.

Bullet wounds create a cavitating defect in the tissues that they pass through. The

tissue damage may be very extensive with high-velocity missiles, and entry and exit

wounds should be noted. Lung tissue is more compliant than the bone and muscles that

comprise the limbs, and enthusiastic resection along the track can be avoided in most

cases. Tetanus prophylaxis and high-dose antibiotics (to cover anaerobic organisms)

should be given. Bullets lodged in the lung do not require removal if they are not

causing any problems.

.

Penetrating wounds of the heart

This is usually the result of a stabbing or shooting incident, but can also be

iatrogenic from central line placement, cardiac catheterization and endomyocardial

biopsy. Cardiac tamponade may occur rapidly even with small amounts of blood in the

pericardium and the condition is recognized by low blood pressure, tachycardia, a high

central venous pressure, pulsus paradoxus and faint heart sound.

Emergency treatment includes aspiration of the pericardium by advancing a wide-

bore needle to the left of the xiphisternum towards the heart. This may hold the situation

until surgical repair is performed.

Complications of thoracic trauma

Pulmonary

1. Atelectasis

2. Acute respiratory distress syndrome

3. Pneumonia

4. Infarction

5. Lung abscess

6. Arteriovenous fistula

7. Bronchial stenosis

8. Tracheoesophageal fistula

Pleural space

1. Empyema

2. Bronchopleural fistula

3. Organized hemothorax

4. Chylothorax

5. Fibrothorax

6. Diaphragmatic hernias

Vascular

1. Thromboembolism

2. Air embolism

3. Pseudoaneurysm

4. Great vessel fistula

7

Chest wall

1. Hernias

2. Persistent pain

Mediastinum

1. Mediastinitis

2. pericarditis

Esophageal rupture

. Esophageal perforation is unusual but catastrophic event. Mortality rate is still high

and can reach up to 20%.

Etiology

1) Iatrogenic (51%)

• instrumentation (esophagoscope, pneumatic dilation, bougienage, NG

tube, ET tube and sclerotherapy).

• operative injury (mediastinoscopy, thyroidectomy, leiomyoma

enucleation, gastric vagotomy…..etc).

2) trauma (20%) penetrating ,blunt, and blast effect.

3) spontaneous (barogenic) rupture 15% follow sudden and drastic increase in intra

abdominal pressure, most commonly following vomiting.

4) Rare causes e.g. tumor, Barrett's ulcer, and viral infection.

Clinical features

Depend on cause, location, and duration since perforation: Pain, dyspnoea,

dysphagia, and fever are found in different combinations.

Mackler`s triad: it is the combination of vomiting, lower thoracic pain, and

subcutaneous emphysema which occur during spontaneous rupture.

Diagnosis

Should be suspected in any case with history of instrumentation and suspicious

symptoms.

• Plain CXR

• Contrast studies: it is the standard measure to document the perforation and

it's location.

• Esophagogastrodoudenoscopy and CT scan as adjunct measures.

Therapy

Principles are:

1) Debridement of infected and necrotic tissues.

2) Elimination of distal obstruction(if present).

3) Secure closure of the perforation( re-enforced primary repair of perforation).

4) Drainage.

5) Establishment of enteral access.

6) Antibiotic therapy.

Treatment options are:

8

A) Non operative therapy, when the leak is minimal and there are no signs of sepsis:

by keeping the patient fasting, broad spectrum AB for 14 days, drainage of pleural

effusions, and total parenteral nutrition.

If the patient condition didn't improve after 24 h, surgical intervention should be

strongly considered.

B) Operative therapy

Absolute criteria for operation are:

1) pneumothorax

2) pneumoperitonium

3) extensive mediastinal emphysema

4) sepsis

5) shock

6) respiratory failure

7) failure of non operative therapy (abscess, empyema)

aspirated foreign bodies

This is a regrettably common occurrence in small children and is often marked by a

choking incident which then apparently passes. Surprisingly large objects can be

inhaled and become lodged in the wider caliber and more vertically placed right main

bronchus. If not removed, an obstructive emphysema may result but, if there is total

occlusion of the bronchus, the air distally will be absorbed and the secretions may

become infected.

There are three possible presentations:

1).asymptomatic

2) wheezing (from airway narrowing) with a persistent cough and signs of obstructive

emphysema.

3) pyrexia with a productive cough from pulmonary suppuration.

A chest radiograph is vital as the object may be radiopaque, or to visualize the

possible complications caused by the foreign body e.g. atelectasis, hyperinflation…etc.

Often it is not radio-opaque or is obscured by the cardiac shadow or the inflammatory

response.

Bronchoscopy is required by an experienced operator with an experienced anesthetist

to administer the anesthetic. The procedure may be very difficult if there is a severe

inflammatory reaction. The rigid bronchoscope is best for retrieving inhaled foreign

bodies. Failure to remove the object may necessitate a bronchotomy through a formal

thoracotomy. If the object has caused chronic lung damage it may be necessary to

remove the affected lobe.

Foreign bodies can be classified into organic (like seeds, tiny food particles….etc.)

which require medical stabilization before bronchoscopy can be done safely, and non

organic foreign bodies (usually radiopaque metallic objects).

Clinical suspicion of foreign body inhalation (in the absence of suggestive history)

should be aroused after failure of medical treatment after one week of admission and

optimum treatment of chest infection.