1

بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم

Lecture -1- Medical Physiology (GIT system)

2

nd

stage Dr. Noor Jawad(2020)

Gastrointestinal tract (Digestive system)

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF GASTROINTESTINAL

Objectives of our lecture:

1. What is the physiological anatomy of the gastrointestinal wall?

2. What is the enteric nervous system?

3. Functional types of movements in GIT?

The digestive system is a tube running from mouth to anus.It

provides the body with a continual supply of water, electrolytes,

vitamins, and nutrients, which requires:

(1) movement of food through the alimentary tract;

(2) secretion of digestive juices and digestion of the food;

(3) absorption of water, various electrolytes, vitamins, and

digestive products;

(4) circulation of blood through the gastrointestinal organs to carry

away the absorbed substances; and

(5) control of all these functions by local, nervous, and hormonal

systems.

2

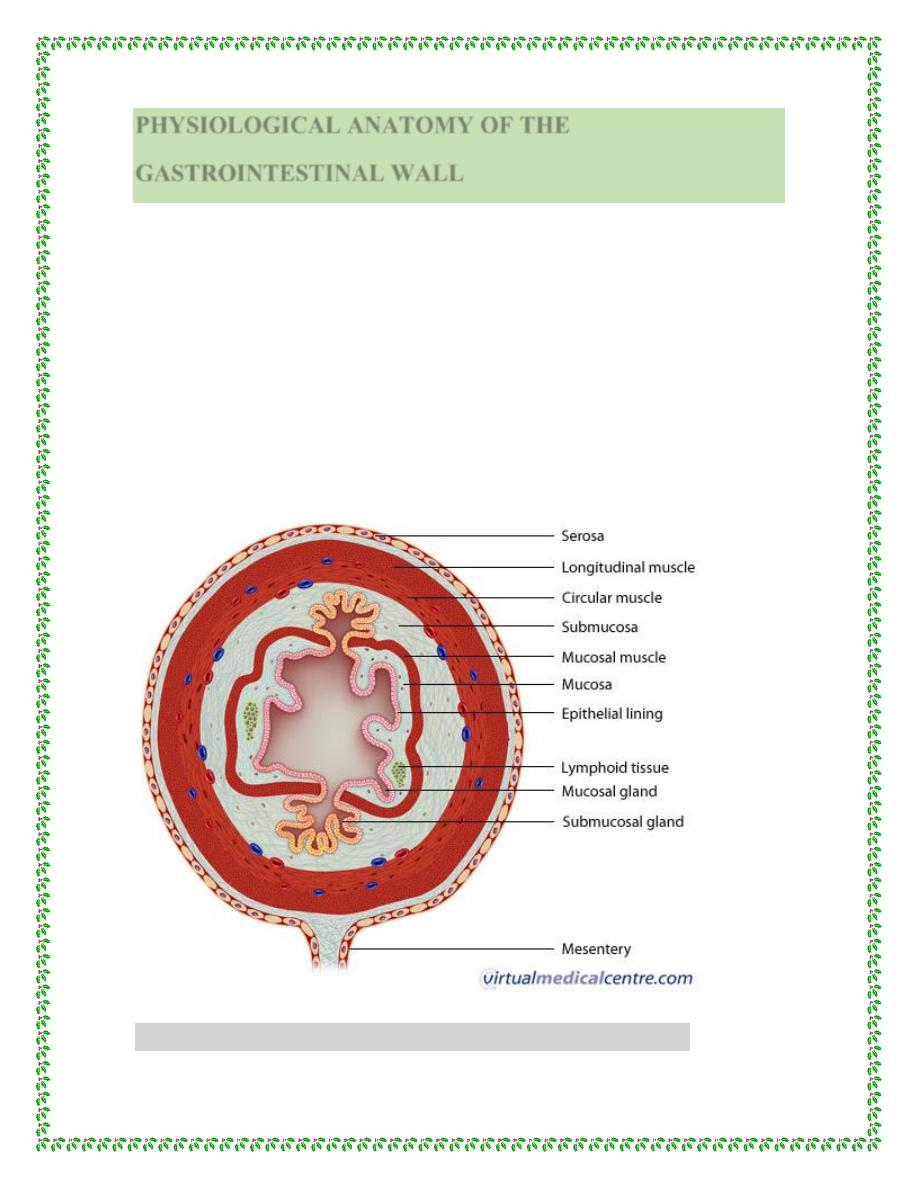

PHYSIOLOGICAL ANATOMY OF THE

GASTROINTESTINAL WALL

Figure below shows a typical cross section of the intestinal wall,

including the following layers from the outer surface inward: (1)

the serosa, (2) a longitudinal smooth muscle layer, (3) a circular

smooth muscle layer, (4) the submucosa, and (5) the mucosa. In

addition, sparse bundles of smooth muscle fibers, the mucosal

muscle, lie in the deeper layers of the mucosa. The motor functions

of the gut are performed by the different layers of smooth muscle.

oss section of the intestinal wall

Figure shows a typical cr

3

NEURAL CONTROL OF GASTROINTESTINAL

FUNCTION—ENTERIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

The gastrointestinal tract has a nervous system all its own called

the enteric nervous system. It lies entirely in the wall of the gut,

beginning in the esophagus and extending all the way to the anus.

The number of neurons in this enteric system is about 100 million,

nearly equal to the number in the entire spinal cord. This highly

developed enteric nervous system is especially important in

controlling gastrointestinal movements and secretion.

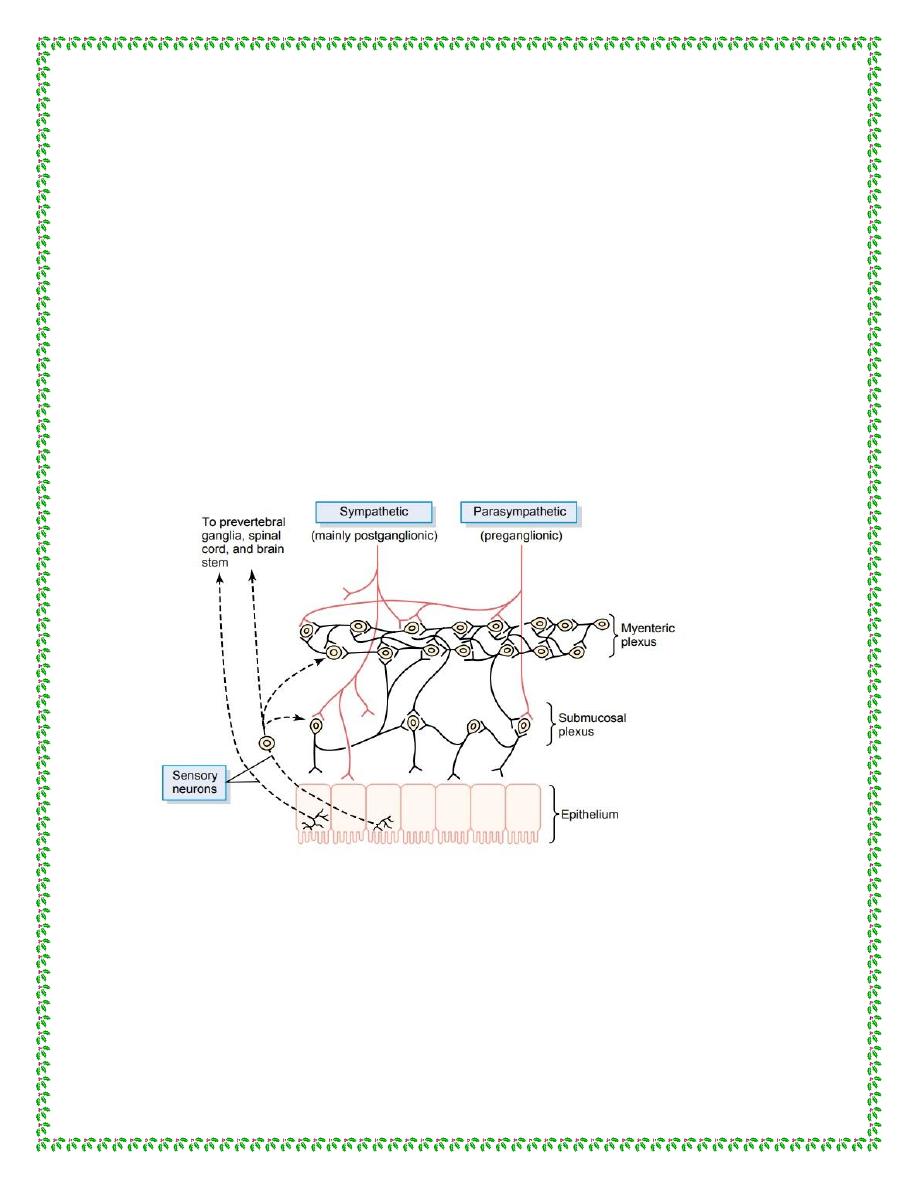

The enteric nervous system is composed mainly of two plexuses,

shown in Figure below: (1) an outer plexus lying between the

longitudinal and circular muscle layers, called the myenteric

plexus or Auerbach’s plexus, and (2) an inner plexus, called the

submucosal plexus or Meissner’s plexus, which lies in the

submucosa.

The myenteric plexus controls mainly the gastrointestinal

movements, and the submucosal plexus controls mainly

gastrointestinal secretion and local blood flow.. Although the

enteric nervous system can function independently of these

extrinsic nerves, stimulation by the parasympathetic and

sympathetic systems can greatly enhance or inhibit gastrointestinal

functions.

4

Also shown in Figure below are sensory nerve endings that

originate in the gastrointestinal epithelium or gut wall and send

afferent fibers to both plexuses of the enteric system, as well as (1)

to the prevertebral ganglia of the sympathetic nervous system, (2)

to the spinal cord, and (3) in the vagus nerves all the way to the

brain stem. These sensory nerves can elicit local reflexes within

the gut wall itself and still other reflexes that are relayed to the gut

from either the prevertebral ganglia or the basal regions of the

brain.

(Figure show (Neural control of the gut wall), showing (1) the myenteric and

submucosal plexuses (black fibers); (2) extrinsic control of these plexuses by the

sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems (red fibers); and (3) sensory

fibers passing from the luminal epithelium and gut wall to the enteric plexuses, then

to the prevertebral ganglia of the spinal cord and directly to the spinal cord and

brain stem)

5

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE MYENTERIC AND

SUBMUCOSAL PLEXUSES

The myenteric plexus consists mostly of a linear chain of many

interconnecting neurons that extends the entire length of the

gastrointestinal tract. Because the myenteric plexus extends all the

way along the intestinal wall and lies between the longitudinal and

circular layers of intestinal smooth muscle, it is concerned mainly

with controlling muscle activity along the length of the gut.

(1)

When this plexus is stimulated, its principal effects are

increased

(2)

increased tonic contraction, or “tone,” of the gut wall;

slightly increased rate

(3)

intensity of the rhythmical contractions;

increased velocity of

(4)

of the rhythm of contraction; and

conduction of excitatory waves along the gut wall, causing more

rapid movement of the gut peristaltic waves.

The myenteric plexus should not be considered entirely excitatory

because some of its neurons are inhibitory; their fiber endings

secrete an inhibitory transmitter, possibly vasoactive intestinal

polypeptide or some other inhibitory peptide. The resulting

inhibitory signals are especially useful for inhibiting some of the

intestinal sphincter muscles that impede movement of food along

successive segments of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the

pyloric sphincter, which controls emptying of the stomach into the

6

duodenum, and the sphincter of the ileocecal valve, which controls

emptying from the small intestine into the cecum.

The submucosal plexus, in contrast to the myenteric plexus, is

mainly concerned with controlling function within the inner wall

of each minute segment of the intestine. For instance, many

sensory signals originate from the gastrointestinal epithelium and

are then integrated in the submucosal plexus to help control local

intestinal secretion, local absorption, and local contraction of the

submucosal muscle that causes various degrees of infolding of the

gastrointestinal mucosa.

TYPES OF NEUROTRANSMITTERS SECRETED BY

ENTERIC NEURONS

Researchers have identified a dozen or more different

neurotransmitter substances that are released by the nerve endings

of different types of enteric neurons, including: (1) acetylcholine,

(2) norepinephrine, (3) adenosine triphosphate, (4) serotonin, (5)

dopamine, (6) cholecystokinin, (7) substance P, (8) vasoactive

intestinal polypeptide, (9) somatostatin, (10) leu-enkephalin, (11)

met-enkephalin, and (12) bombesin.

Acetylcholine most often excites gastrointestinal activity.

Norepinephrine almost always inhibits gastrointestinal activity, as

does epinephrine, which reaches the gastrointestinal tract mainly

7

by way of the blood after it is secreted by the adrenal medullae into

the circulation.

FUNCTIONAL TYPES OF MOVEMENTS IN THE

GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Two types of movements occur in the gastrointestinal tract: (1)

propulsive movements, which cause food to move forward along

the tract at an appropriate rate to accommodate digestion and

absorption, and (2) mixing movements, which keep the intestinal

contents thoroughly mixed at all times.

PROPULSIVE MOVEMENTS—PERISTALSIS

A contractile ring appears around the gut and then moves forward;

this mechanism is analogous to putting one’s fingers around a thin

distended tube, then constricting the fingers and sliding them

forward along the tube. Any material in front of the contractile ring

is moved forward. Peristalsis is an inherent property of many

syncytial smooth muscle tubes; stimulation at any point in the gut

can cause a contractile ring to appear in the circular muscle, and

this ring then spreads along the gut tube. (Peristalsis also occurs in

the bile ducts, glandular ducts, ureters, and many other smooth

muscle tubes of the body.)

The usual stimulus for intestinal peristalsis is distention of the gut.

That is, if a large amount of food collects at any point in the gut,

8

the stretching of the gut wall stimulates the enteric nervous system

to contract the gut wall 2 to 3 centimeters behind this point, and a

contractile ring appears that initiates a peristaltic movement. Other

stimuli that can initiate peristalsis include chemical or physical

irritation of the epithelial lining in the gut. Also, strong

parasympathetic nervous signals to the gut will elicit strong

peristalsis.

MIXING MOVEMENTS

Mixing movements differ in different parts of the alimentary tract.

In some areas, the peristaltic contractions cause most of the

mixing. This is especially true when forward progression of the

intestinal contents is blocked by a sphincter so that a peristaltic

wave can then only churn the intestinal contents, rather than

propelling them forward. At other times, local intermittent

constrictive contractions occur every few centimeters in the gut

wall. These constrictions usually last only 5 to 30 seconds; new

constrictions then occur at other points in the gut, thus “chopping”

and “shearing” the contents first here and then there.

Thank you

References : Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology,

thirteen edition.