Hirschsprung’s diseaseHirschsprung’s disease is characterised by the congenital absence of intramural ganglion cells and the presence of hypertrophicnerves in the distal large bowel. The affected gut is tonically contracted causing functional bowel obstruction. The aganglionosis is restricted to the rectum and sigmoid colon in 75% of patients (short segment), involves the proximal colon in 15% (long segment) and affects the entire colon

and a portion of terminal ileum in 10% (total colonic aganglionosis).A transition zone exists between the dilated, proximal, normallyinnervated bowel and the narrow, distal aganglionic segment.Hirschsprung’s disease may be familial or associated withDown’s syndrome or other genetic disorders. Gene mutations havebeen identified on chromosome 10 and on chromosome 13 in some patients

Hirschsprung’s disease typically presents in the neonatal period with delayed passage of meconium, abdominal distension and bilious vomiting but it may not be diagnosed until later in childhood or even adult life, when it manifests as severe chronic constipation.Enterocolitis is a potentially fatal complication of the disease.

Definitive diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease depends on histological examination of an adequate rectal biopsy by an experienced pathologist. A contrast enema may show the extent of the aganglionic segment

TreatmentSurgery aims to remove the aganglionic segmentand bring down healthy ganglionic bowel to the anus; these‘pull-through’ operations (e.g. Swenson, Duhamel, Soave andtransanal procedures) can be done in a single stage or in several stages after first establishing a proximal stoma in normally innervated bowel.

ULCERATIVE COLITISAetiologyThe cause of UC is unknown. There is probably a genetic contribution with no clear Mendelian pattern of inheritance. It has been shown that 15% of patients with UC have a first-degree relative with inflammatory bowel disease. UC is more common inCaucasians than in blacks or Asians. In spite of intensive bacteriological studies, no organisms or group of organisms can be incriminated. Smoking seems to have a protective effect

UC is thought to be an immune disorder in individuals with yet unknown susceptibility genes or a hypersensitivity reaction to an external antigen.

EpidemiologyThe disease has been rare in eastern populationsbut is now being reported more commonly, suggesting an environmental cause that has developed as a result of an increasing ‘westernisation’ of diet and/or social habits and better diagnostic facilities. The sex ratio is equal in the first four decades of life. from the age of 40 years, the incidence in females falls whereas it remains the same in males. It is uncommon before the age of 10 years, and most patients are between the ages of 20 and 40 years at diagnosis.

PathologyIn 95% of cases, the disease starts in the rectum and spreadsproximally. The rectum is involved in all circumstances . It is a diffuse inflammatory disease, primarily affecting the mucosa andsuperficial submucosa, and only in severe disease are the deeperlayers of the intestinal wall affected. There are multiple minuteulcers.

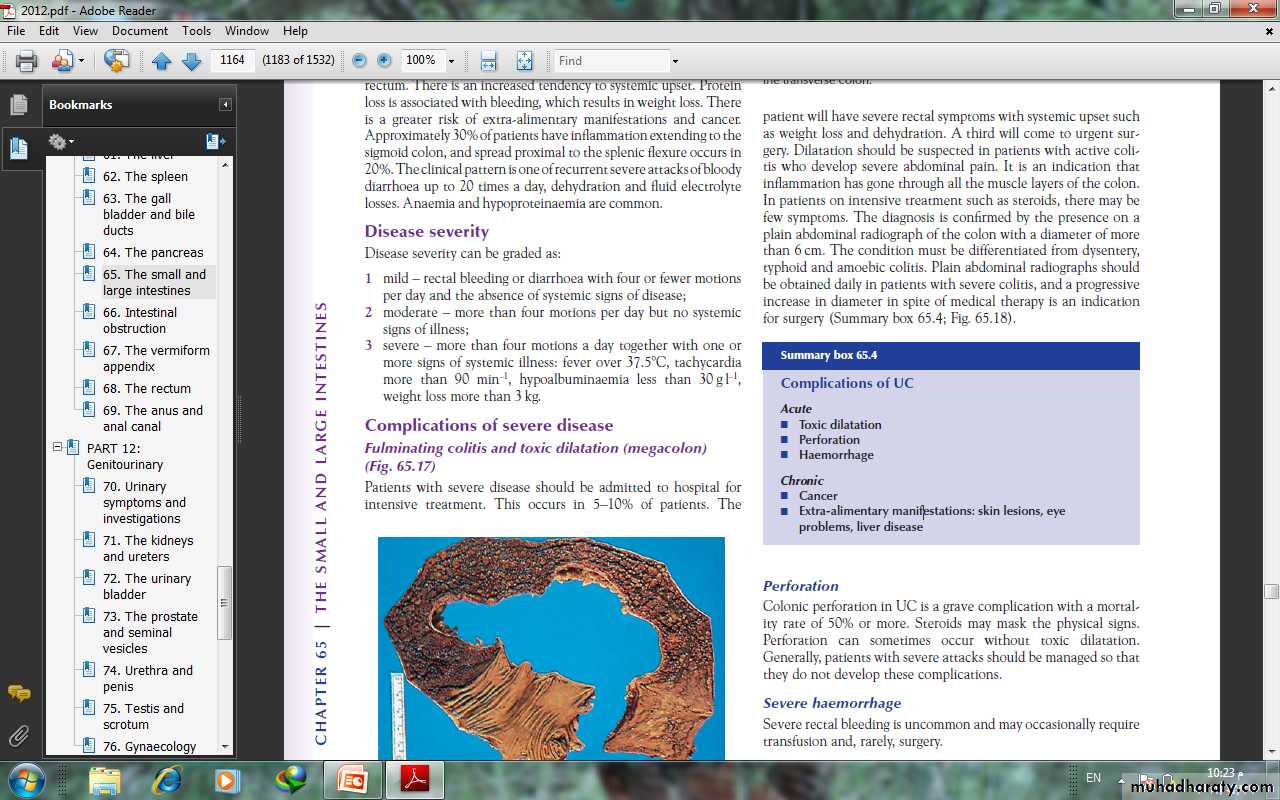

When the disease is chronic, inflammatory polyps(pseudopolyps) occure and may be numerous.In severe fulminant colitis, a section of the colon, usuallythe transverse colon, may become acutely dilated, with the risk ofperforation (‘toxic megacolon’). On microscopic investigation,there is an increase in inflammatory cells in the lamina propria,the walls of crypts are infiltrated by inflammatory cells and thereare crypt abscesses. There is depletion of goblet cell mucin. Withtime, these changes become severe, and precancerous changescan develop (= severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ).

SymptomsThe first symptom is watery or bloody diarrhoea; there may be arectal discharge of mucus that is either blood-stained or purulent.Pain as an early symptom is unusual

In most cases, the disease is chronic and characterised by relapses and remissions. In general,a poor prognosis is indicated by (1) a severe initial attack, (2) disease involving the whole colon (3) increasing age, especially after 60 years.

ProctitisAs most of the colon ishealthy, the stool is formed or semiformed, and the patient isoften severely troubled by tenesmus and urgency andextra-alimentary manifestations are rare.

Colitis Diarrhoea usually implies that there is active disease proximal to the rectum. There is an increased tendency to systemic upset. Protein loss is associated with bleeding, which results in weight loss. There is a greater risk of extra-alimentary manifestations and cancer. The clinical pattern is one of recurrent severe attacks of bloody diarrhoea up to 20 times a day, dehydration and fluid electrolyte losses. Anaemia and hypoproteinaemia are common.

Disease severityDisease severity can be graded as:1 mild – rectal bleeding or diarrhoea with four or fewer motionsper day and the absence of systemic signs of disease;2 moderate – more than four motions per day but no systemicsigns of illness;3 severe – more than four motions a day together with one ormore signs of systemic illness: fever over 37.5°C, tachycardiamore than 90 min–1, hypoalbuminaemia less than 30 g l–1,weight loss more than 3 kg.

Complications of severe diseaseFulminating colitis and toxic dilatation (megacolon)Patients with severe disease should be admitted to hospital forintensive treatment. This occurs in 5–10% of patients. The patient will have severe rectal symptoms with systemic upset suchas weight loss and dehydration. In patients on intensive treatment such as steroids, there may befew symptoms. The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence on a plain abdominal radiograph of the colon with a diameter of more than 6 cm. The condition must be differentiated from dysentery, typhoid and amoebic colitis. Plain abdominal radiographs should be obtained daily in patients with severe colitis, and a progressive increase in diameter in spite of medical therapy is an indicationfor surgery

PerforationColonic perforation in UC is a grave complication with a mortalityrate of 50% or more Severe haemorrhageSevere rectal bleeding is uncommon and may occasionally requiretransfusion and, rarely, surgery

InvestigationsA plain abdominal film can often show the severity of disease.Faeces are present only in parts of the colon that are normal oronly mildly inflamed. Mucosal islands can sometimes be seen.

Barium enemaThe principal signs are :• loss of haustration, especially in the distal colon;• mucosal changes caused by granularity;• pseudopolyps;• in chronic cases, a narrow contracted colon.

SigmoidoscopySigmoidoscopy is essential for diagnosis of early cases and milddisease not showing up on a barium enema. The initial findingsare those of proctitis: the mucosa is hyperaemic and bleeds ontouch, and there may be a pus-like exudate. Where there hasbeen remission and relapse, there may be the presence of pseudopolyps. Later, tiny ulcers may be seenthat appear to coalesce. This is different from the picture ofamoebic dysentery, in which there are large, deep ulcers withintervening normal mucosa.

Colonoscopy and biopsyThis has an important place in management:1 to establish the extent of inflammation;2 to distinguish between UC and Crohn’s colitis;3 to monitor response to treatment;4 to assess longstanding cases for malignant change

Bacteriology A stool specimen needs to be sent for microbiology analysis when UC is suspected. Other infective causes include Shigella and amoebiasis.Pseudomembranous colitis occurs in hospital patients on antibiotictreatment and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs(NSAIDs). The causative organism is Clostridium difficile.Immunocompromised patients are at risk of infective proctocolitisfrom cytomegalovirus and cryptosporidia

Extraintestinal manifestationsArthritis occurs in around 15% of patients and is of the large jointpolyarthropathy type, affecting knees, ankles, elbows and wrists.Sacroiliitis and ankylosing spondylitis are 20 times more commonin patients with UC.Bile duct cancer is a rare complication, and colectomy does not

• skin lesions: erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum or aphthous ulceration;• eye problems: iritis;• liver disease: sclerosing cholangitis has been reported in up to70% of cases. Diagnosis is by ERCP, which demonstrates thecharacteristic alternating stricturing and bleeding of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts.

TreatmentMedical treatment of an acute attackCorticosteroids are the most useful drugs and can be given eitherlocally for inflammation of the rectum or systemically when thedisease is more extensive. One of the 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) derivatives can be given both topically and systemically.Their main function is in maintaining remission rather thantreating an acute attack. Non-specific anti-diarrhoeal agentshave no place in the routine management of UC

Mild attacksPatients with a mild attack will usually respond torectally administered steroids or oral prednisolone 20 mg day–1 is given over a 3- to 4-week period.One of the 5-ASA compounds should be given concurrently.Moderate attacksThese patients should be treated with oral prednisolone 40 mgday–1, twice-daily steroid enemas and 5-ASA.

Severe attacksThese patients must be regarded as medical emergencies andrequire immediate admission to hospital. It is important to monitor vital signs (pulse, temperature andblood pressure). A stool chart should be kept.Increasing abdominal girth is a potential sign of megacolon developing.A plain abdominal radiograph is taken daily and inspectedfor dilatation of the transverse colon of more than 5.5 cm.

The presence of mucosal islands or intramural gas on plain radiographs increasing colonic diameter or a sudden increasein pulse and temperature may indicate a colonic perforation. Fluidand electrolyte balance is maintained, anaemia is corrected andadequate nutrition is provided, parenteral nutrition may be indicated.The patient is treated with intravenous hydrocortisone100–200 mg four times daily.

There is no evidence that antibiotics modify the course of a severe attack. Some patients are treated with azathioprine or ciclosporin A to induce remission. If there is failure to gain an improvement within 3–5 days, then surgery must be seriously considered. Prolonged high-dose intravenous steroid therapy is fraught with danger.

Indications for surgery :• severe or fulminating disease failing to respond to medicaltherapy;• chronic disease with anaemia, frequent stools, urgency andtenesmus;• steroid-dependent disease – here, the disease is not severe butremission cannot be maintained without substantial doses ofsteroids;• the risk of neoplastic change: patients who have severe dysplasiaon review colonoscopy;• extraintestinal manifestations;• rarely, severe haemorrhage or stenosis causing obstruction.

Operations--the ‘first aid procedure’ is a total abdominal colectomy and ileostomy. This has the advantagethat the patient recovers quickly, the histology of the resectedcolon can be checked, and restorative surgery can be contemplatedat a later date.--Proctocolectomy and ileostomyThis is the procedure associated with the lowest complicationrate. It is indicated in patients who are not candidates for restors.

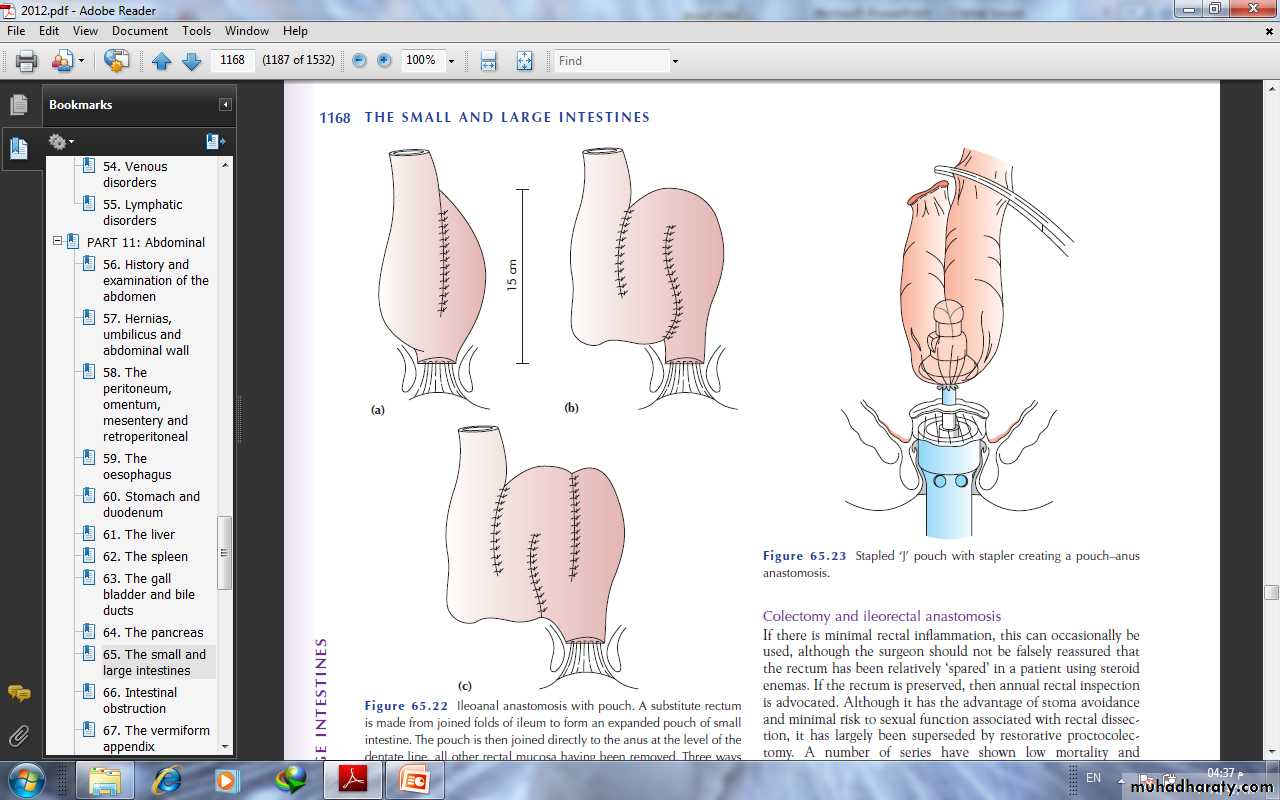

--Restorative proctocolectomy with an ileoanal pouch (Parks)In this operation, a pouch is made out of ileum as asubstitute for the rectum and sewn or stapled to the anal canal.This avoids a permanent stoma.

--Colectomy and ileorectal anastomosisIf there is minimal rectal inflammation, this can occasionally beused, although the surgeon should not be falsely reassured thatthe rectum has been relatively ‘spared’ in a patient using steroidenemas

Ileostomy with a continent intra-abdominal pouch (Kock’sprocedure)A reservoir is made from 30 cm of ileum and, just beyond this, aspout is made by inverting the efferent ileum into itself to give acontinent valve just below skin level.