Fifth Stage

Internal Medicine

Dr. Abbas / Lec . 9

1

HEMORRHAGIC CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE

15% of stroke

10% intra-cerebral hemorrhage

5% subarachnoid hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Causes

1-Hypertension

2-Amyloid (congophilic) angiopathy

3-Arteriovenous malformation

4-Bleeding diathesis

5-Drugs (amphetamines, cocaine, anticoagulants, thrombolytics)

6-head injury

7-tumour

In hypertensive ICH :

Rupture of microaneurysms (Charcot-Bouchard aneurysms, 0.8-1.0 mm

diameter) and degeneration of small deep penetrating arteries are the principal

pathology. Such hemorrhage is usually massive, often fatal and occurs in

chronic hypertension and at well-defined sites - basal ganglia, pons, cerebellum

and subcortical white matter .

In normotensive patients,

particularly over 60 years, lobar intracerebral hemorrhage occurs - in the

frontal, temporal, parietal or occipital cortex. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

(rare) is the cause in some of these hemorrhages, and the tendency to re-bleed

is associated with particular apolipoprotein E genotypes

Clinical Manifestations

Although not particularly associated with exertion, intracerebral hemorrhages

almost always occur while the patient is awake and sometimes when stressed.

The hemorrhage generally presents as the abrupt onset of focal neurologic

deficit. Seizures are uncommon. The focal deficit typically worsens steadily

over 30–90 min and is associated with a diminishing level of consciousness and

signs of increased ICP, such as headache and vomiting

The putamen is the most common site for hypertensive hemorrhage, and the

adjacent internal capsule is usually damaged

Contralateral hemiparesis is therefore the sentinel sign.. When hemorrhages

are large, drowsiness gives way to stupor as signs of upper brainstem

compression appear. Coma ensues, accompanied by deep, irregular, or

2

intermittent respiration, a dilated and fixed -pupil, and decerebrate rigidity. In

milder cases, edema in adjacent brain tissue may cause progressive

deterioration over 12–72 h.

In pontine hemorrhages, deep coma with quadriplegia usually occurs over a

few minutes. There is often prominent decerebrate rigidity and "pin-point" (1

mm) pupils that react to light., severe hypertension, and hyperhidrosis are

common. Death often occurs within a few hours, but small hemorrhages are

compatible with survival

Cerebellar haemorrhage There is headache and rapid reduction of

consciousness with signs of brainstem origin (e.g. nystagmus, ocular palsies).

Gaze deviates towards the haemorrhage. Skew deviation may develop.

There are unilateral or bilateral cerebellar signs, if the patient is awake.

Cerebellar haemorrhage sometimes causes acute hydrocephalus. Emergency

surgical clot evacuation is often necessary after imaging

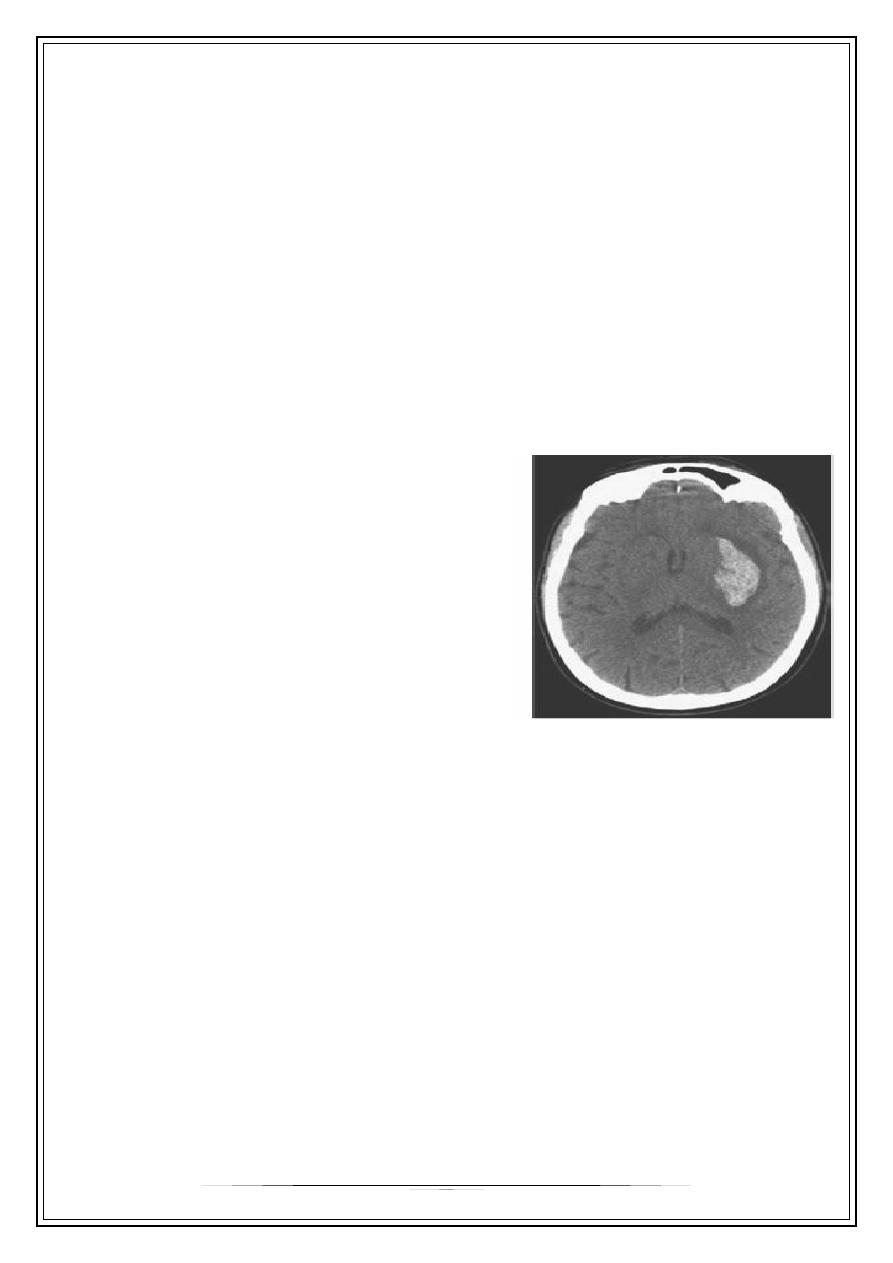

Diagnosis

Intracerebral hemorrhage often cannot be

distinguished from other types of strokes

based on clinical findings alone. The test of

choice for making the diagnosis is a non–

contrast-enhanced CT scan that shows

areas of hemorrhage as zones of increased

density, which may or may not have

associated regions of decreased density

indicating infarction.

Treatment

General Measures

With initial care directed at maintenance of the airway, oxygenation, nutrition,

and prevention and treatment of secondary complications.

Optimal blood pressure treatment is uncertain, although the general guidelines

for excessive hypertension and reduction of cerebral perfusion apply as for

ischemic strokes.

There is no accepted protocol for the management of increased intracranial

pressure; osmotherapy, hyperventilation, and neuromuscular paralysis rarely

are beneficial.

Fluid management should maintain euvolemia; fluid restriction or volume

expansion is not of proven value.

Seizures are particularly harmful in critically ill patients and are treated despite

lack of data from randomized trials.

Maintenance of normal body temperature is theoretically desirable because

fever may accelerate tissue destruction

3

Medical Therapy

Intravenous administration of recombinant factor VIIa within 4 hours after

onset reduces the volume of hemorrhage and surrounding cerebral edema, as

measured by CT, and improves neurologic outcomes at 90 days despite an

increase in ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction [.

2

]

Corticosteroids may increase the risk for infectious complication

Surgical Therapy

The goal of surgical treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage is to remove as

much blood clot as possible as quickly as possible. Ideally, surgery should

remove the underlying cause, such as an AVM, and prevent hydrocephalus.

Early surgical intervention to evacuate intracerebral hematomas within 24

hours is no better than medical therapy .However, patients who have

cerebellar hemorrhages and are deteriorating because of brain stem

compression and hydrocephalus caused by ventricular obstruction are still

recommended by some for removal of the clot or amputation of part of the

cerebellum, although no proof exists to support this approach

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) means spontaneous arterial bleeding into

the subarachnoid space, and is usually clearly recognizable clinically by its

dramatic onset. SAH accounts for some 5% of strokes and has an annual

incidence of 6 per 100 000 .

Causes

1-saccular or berry aneurysm 85%

2-non-aneurysmal hemorrhage [10%]

3-AV malformation [5%]

Saccular aneurysms develop on the circle of Willis and adjacent arteries.

Common sites are at the following arterial junctions:

*Between posterior communicating and internal carotid artery - posterior

communicating artery aneurysm

*Between anterior communicating and anterior cerebral artery - anterior

communicating artery aneurysm

*At a bifurcation or at the trifurcation of the middle cerebral artery - middle

cerebral artery aneurysm .

Aneurysms cause symptoms either by spontaneous rupture, when there is

usually no preceding history, or by direct pressure on surrounding structures;

for example, an enlarging unruptured posterior communicating artery

aneurysm is the commonest cause of a painful third nerve palsy

Arteriovenous malformation (AVM) This is a collection of arteries and veins of

developmental origin, usually within the hemisphere. An AVM may also cause

4

epilepsy, often focal. Once an AVM has ruptured the tendency is to rebleed -

10% will then do so annually

Clinical features of SAH

There is a sudden devastating headache, often occipital. This is usually

followed by vomiting and often by coma. The patient remains comatose or

drowsy for several hours to several days, or longer. Less severe headaches

cause difficulty but SAH is a

possible

diagnosis in any sudden headache.

After major SAH there is neck stiffness and a positive Kernig's sign.

Papilloedema is sometimes present and accompanied by retinal and subhyaloid

haemorrhage (tracking beneath the retinal hyaloid membrane). Minor bleeds

cause few signs, but almost invariably headache

Investigations

CT imaging is the initial investigation of choice

Subarachnoid or intraventricular blood is usually seen.

Lumbar puncture is not necessary if SAH is confirmed by CT, but should be

performed if doubt remains. The CSF becomes yellow (xanthochromic) several

hours after SAH. Visual inspection of the supernatant CSF is usually sufficiently

reliable for diagnosis, but there is a move to use spectrophotometry to

estimate bilirubin released from lysed cells to define with certainty SAH in

doubtful cases.

MR angiography is usually performed in all potentially fit for surgery, i.e.

generally below 65 years and not in coma. In some cases, no aneurysm is

found despite a definite SAH .

Complications

1-hydrocephalus

Blood In the subarachnoid space can lead to obstruction of CSF flow and

hydrocephalus. This can be asymptomatic but may cause deteriorating

consciousness after SAH. Diagnosis is by CT. Shunting may be required .

2-Severe arterial spasm (visible on cerebral angiography and a cause of

coma or stroke) sometimes complicates SAH. It is a poor prognostic sign .

3-Rebleeding

Approximately 30% of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

rebleed during the first month, and the incidence is highest during the first 2

weeks after the initial episode. Patients with unrepaired aneurysms who

survive their initial bleeding for more than 1 month have a 2 to 3% annual risk

of rebleeding

4-Seizures

Seizures may occur shortly after subarachnoid hemorrhage in 15 to 90% of

patients. Seizures are thought to be caused by cortical damage from bleeding

into the neocortex or from ischemic necrosis related to vasospasm. The

5

development of persistent epilepsy is unusual. Prophylactic anticonvulsant

therapy has not been useful

Non-neurologic Complications

1-Cardiac complications occur as a consequence of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

In the acute phases of subarachnoid hemorrhage, electrocardiographic

patterns can mimic acute myocardial infarction, a pattern of deep inverted T

waves across the pericardium is classic. Appropriate biomarker assays and

repeat electrocardiograms are needed to document true myocardial damage.

2-hyponatremia

is the most common electrolyte abnormality after subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Sodium loss, which is typically mild, may occur in up to 25% of patients. The

natriuresis has been attributed to inappropriate levels of antidiuretic hormone,

but this hypothesis has not been proved. Hyponatremia can itself result in a

decreased level of consciousness and seizures, but it is often impossible to

distinguish the effects of hyponatremia from the other possible causes of these

neurologic abnormalities

Management

Immediate treatment of SAH is bed rest and supportive measures.

Hypertension should be controlled. Dexamethasone is often prescribed, to

reduce cerebral oedema; it also is believed to stabilize the blood-brain barrier.

Nimodipine, a calcium-channel blocking agent, reduces mortality.

All surviving SAH cases should be discussed urgently with a specialist

neurosurgical centre. Nearly half SAH cases are either dead or moribund before

they reach hospital. Of the remainder, a further 10-20% rebleed and die in the

next several weeks. Delay or failure to diagnose SAH without coma (e.g.

mistaking it for migraine) contributes to this mortality .

Patients who remain comatose or with persistent severe deficits have a poor

prognosis. In others, where angiography demonstrates aneurysm, a direct

neurosurgical approach to clip the neck of the aneurysm is carried out. In

selected cases the results of surgery are excellent. Invasive radiological

techniques, such as inserting a fine wire coil into an aneurysm are also used.

Direct surgery, microembolism and focal radiotherapy ('gamma knife') are used

in AVM .

Thank you,,,