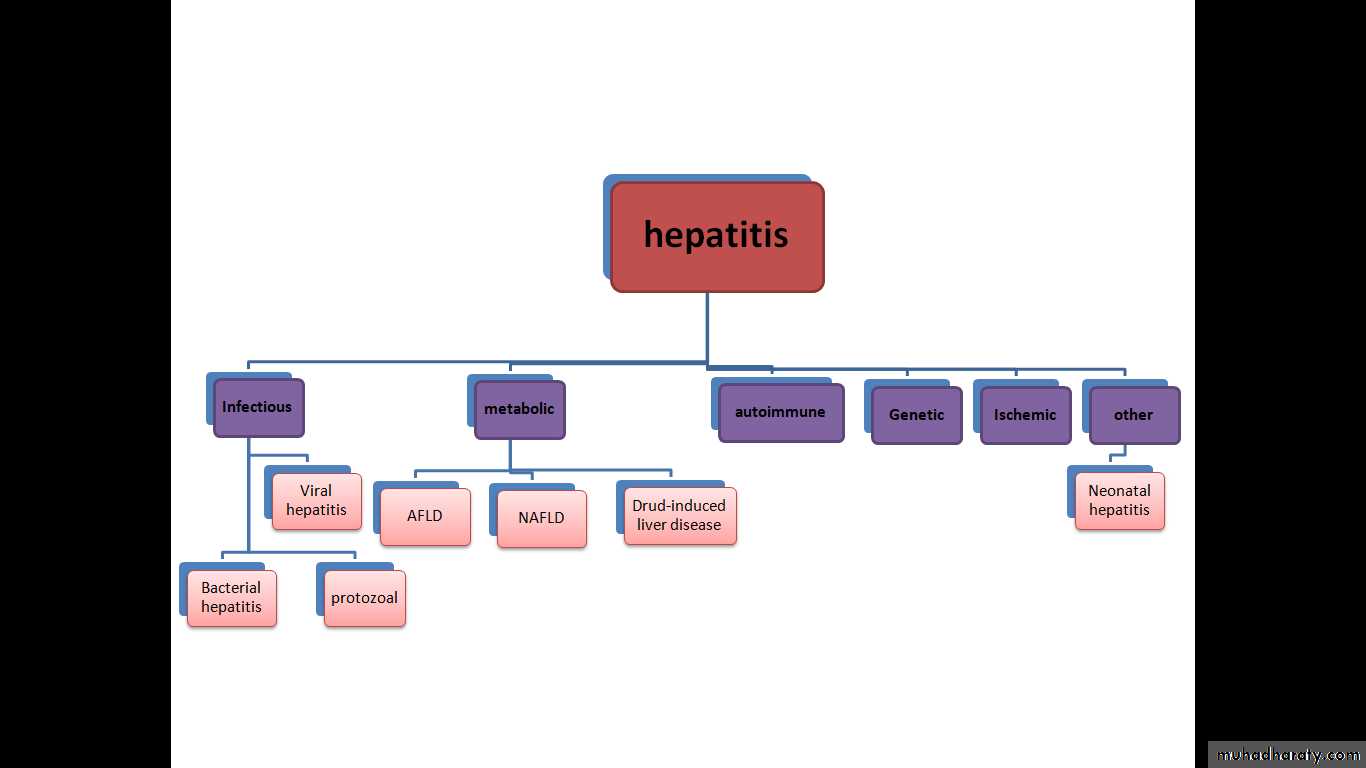

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver. The condition can be self-limiting or can progress to fibrosis (scarring), cirrhosis or liver cancer. Hepatitis viruses are the most common cause of hepatitis in the world but other infections (bacterial and protozoal), toxic substances (e.g. alcohol, certain drugs), and autoimmune diseases can also cause hepatitis.

Hepatitis

Causes

The specific mechanism varies and depends on the underlying cause of the hepatitis. Generally, there is an initial insult that causes liver injury and activation of an inflammatory response, which can become chronic, leading to progressive fibrosis and cirrhosis.Viral hepatitis

The pathway by which hepatic viruses cause viral hepatitis is best understood in the case of hepatitis B and C. The viruses do not directly cause apoptosis (cell death). infection of liver cells activates the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system leading to an inflammatory response which causes cellular damage and death. infection can either lead to clearance (acute disease) or persistence (chronic disease) of the virus. The chronic presence of the virus within liver cells results in multiple waves of inflammation, injury and wound healing that over time lead to scarring or fibrosis and culminate in hepatocellular carcinoma. Individuals with an impaired immune response are at greater risk of developing chronic infection.Mechanism

Steatohepatitis

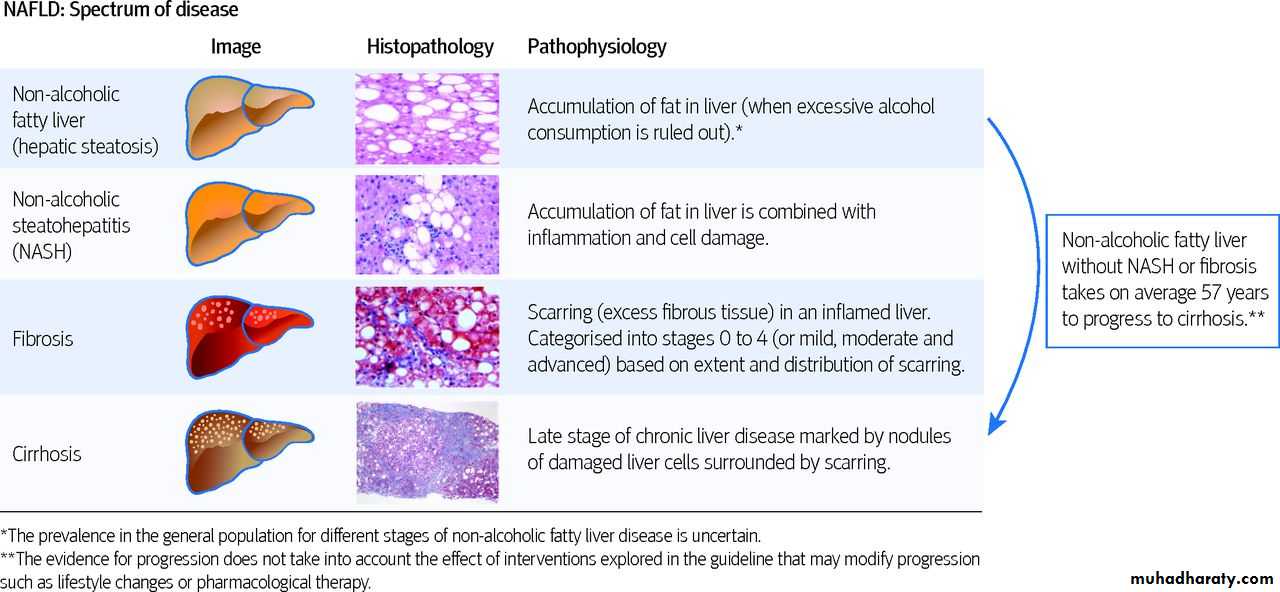

Steatohepatitis is seen in both alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease and is the culmination of a cascade of events that began with injury.

In non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, this cascade is initiated by changes in metabolism associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and lipid dysregulation.

In alcoholic hepatitis, chronic excess alcohol use is the culprit. Though the inciting event may differ, but the progression of events is similar and begins with accumulation of free fatty acids (FFA) and their breakdown products in the liver cells in a process called steatosis. This initially reversible process overwhelms the hepatocyte's ability to maintain lipid homeostasis leading to a toxic effect as fat molecules accumulate and are broken down in the setting of an oxidative stress response. Over time, this abnormal lipid deposition triggers the immune system resulting in the production of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF that cause liver cell injury and death. These events mark the transition to steatohepatitis and in the setting of chronic injury, fibrosis eventually develops setting up events that lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Mechanism

Microscopically, changes that can be seen include:-steatosis with large and swollen hepatocytes (ballooning),

evidence of cellular injury and cell death (apoptosis, necrosis),

evidence of inflammation in particular in zone 3 of the liver,

variable degrees of fibrosis and Mallory bodies.

Hepatitis has a broad spectrum of presentations that range from a complete lack of symptoms to severe liver failure. The acute form of hepatitis, generally caused by viral infection, is characterized by constitutional symptoms that are typically self-limiting. Chronic hepatitis presents similarly, but can manifest signs and symptoms specific to liver dysfunction with long-standing inflammation and damage to the organ.

Acute viral hepatitis follows three distinct phases:

• The initial prodromal phase (preceding symptoms) involves non-specific and flu-like symptoms common to many acute viral infections. These include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, poor appetite, joint pain, and headaches.Fever, when present, is most common in cases of hepatitis A and E. Late in this phase, people can experience liver-specific symptoms, including choluria (dark urine) and clay-colored stools.• Yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes follow the prodrome after about 1–2 weeks and can last for up to 4 weeks.The non-specific symptoms seen in the prodromal typically resolve by this time, but people will develop an enlarged liver and right upper abdominal pain or discomfort.10–20% of people will also experience an enlarged spleen, while some people will also experience a mild unintentional weight loss.

• The recovery phase is characterized by resolution of the clinical symptoms of hepatitis with persistent elevations in liver lab values and potentially a persistently enlarged liver. All cases of hepatitis A and E are expected to fully resolve after 1–2 months.Most hepatitis B cases are also self-limiting and will resolve in 3–4 months. Few cases of hepatitis C will resolve completely.

Signs and symptoms

Fulminant hepatitis

Fulminant hepatitis, or massive hepatic cell death, is a rare and life-threatening complication of acute hepatitis that can occur in cases of hepatitis B, D, and E, in addition to drug-induced and autoimmune hepatitis.In addition to the signs of acute hepatitis, people can also demonstrate signs of coagulopathy and encephalopathy (confusion, disorientation, and sleepiness).Chronic hepatitis

Acute cases of hepatitis are seen to be resolved well within a six-month period. When hepatitis is continued for more than six months it is termed chronic hepatitis.Chronic hepatitis is often asymptomatic early in its course and is detected only by liver laboratory studies for screening purposes or to evaluate non-specific symptoms.As the inflammation progresses, patients can develop constitutional symptoms similar to acute hepatitis.[Jaundice can occur as well, but much later in the disease process and is typically a sign of advanced disease.Chronic hepatitis interferes with hormonal functions of the liver which can result in acne, hirsutism and amenorrhea in women. Extensive damage and scarring of the liver over time defines cirrhosis. This results in jaundice, weight loss, coagulopathy, ascites and peripheral edema. Cirrhosis can lead to other life-threatening complications such as hepatic encephalopathy, esophageal varices, hepatorenal syndrome, and liver cancer.Signs and symptoms

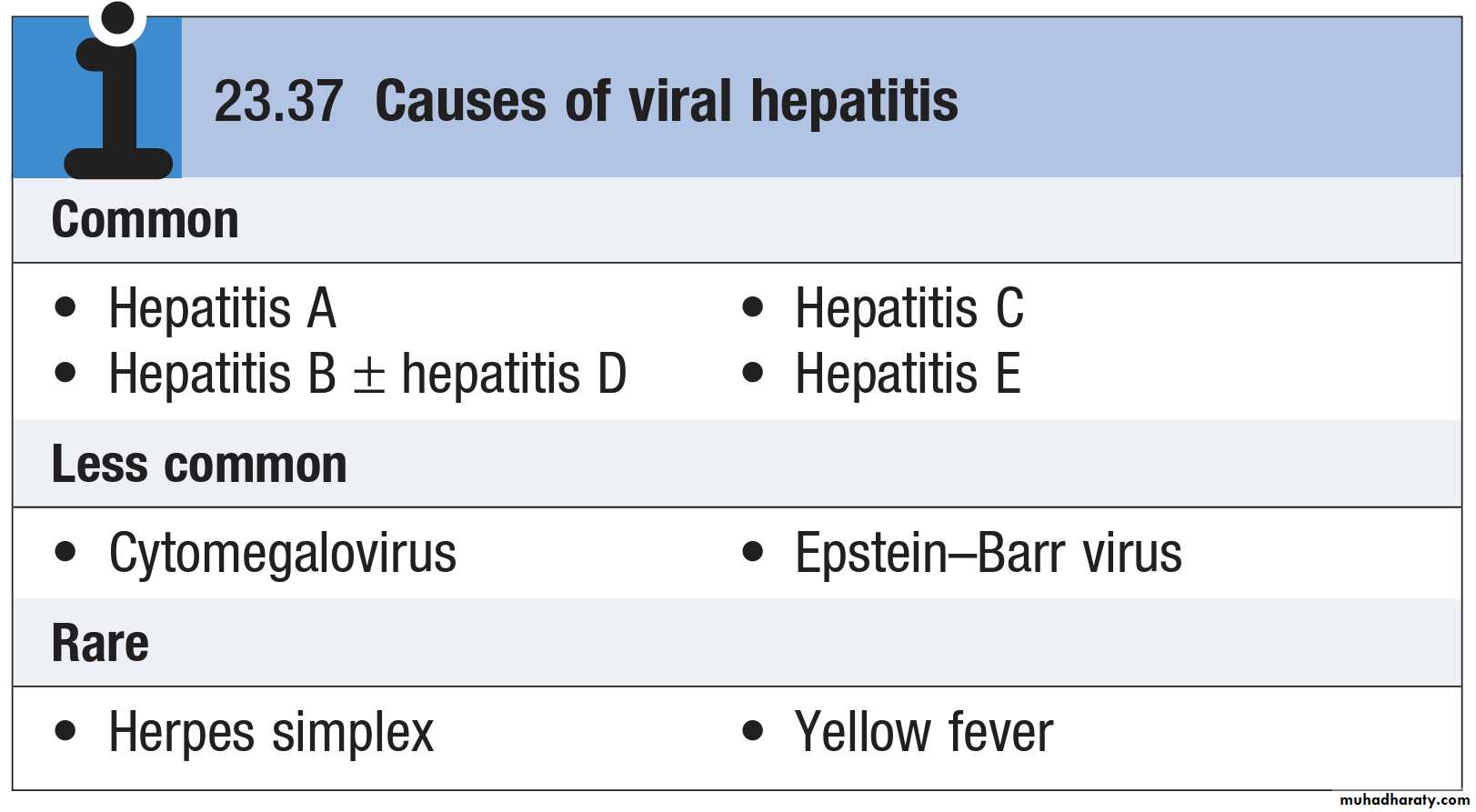

Viral hepatitisThe Causative Agent:

• Hepatitis A Virus:• 27 nm picornavirus single stranded RNA virus

• Nonenveloped, acid and heat stable

Reservoir of infection:

• Humans are the only reservoirs of infection (Acute cases because there is No chronic carrier state)Hepatitis A Transmission

• Close personal contact (Household or sexual contact)

• Daycare centers.

• Fecal-oral contamination of food or water (Food handlers and Raw shellfish).

• Blood-borne (rare).

• Injecting drug users.

Incubation Period:15-50 days or (2-6 weeks)

Hepatitis A infectionInitially (pre-ecteric stage): Sudden onset of fever, anorexia, malaise, nausea, vomiting, & abdominal discomfort. Some patients Might develop myalgia, arthralgia & alteration of smell & taste. Later (after several days to one week) : Jaundice with dark urine & clay stool.

Asymptomatic (anicteric) infection is common especially in children.

Symptomatic (Icteric) infection occurs in:

• <10% of Children under 6 years of age.

• 50-60% of Children from 6-14 years old.• 70%-80% of adults and children over 14 years.

Clinical Features:

Clinical features (The clinical course of acute hepatitis A is indistinguishable from that of other types of acute viral hepatitis )

Urine bilirubin in the pre-ecteric stage

Liver function test (rises in the level of ALT & AST)

Diagnosis is established by the detection of :

• IgM Anti HAV : appears 4 wks after exposure and may remain detectable for 4-6 months. It indicates acute infection

• IgG Anti-HAV : peaks during convalescence and persists for life. Indicates immunity acquired from past infection or immunization

Diagnosis

General:• Good sanitation & personal hygiene with special emphasis on hand washing.

• Provision of safe water supply & proper sewage disposal.

Specific:

Measures for patients :• Isolation is not necessary

• Strict personal hygiene is required in homes where a case has occurred

• Treatment of patients

- No specific treatment

- Bed rest is essential

Measures for contacts:

• Investigation of contacts searching for other cases

• Post-exposure prophylaxis: Immune globulin 0.02 ml/kg IM within 2 weeks of exposure.

Indications of contact measures:

• Sexual contacts• Close household contacts.

• Staff and children at day care center exposed to a patient with Hepatitis A.

• Food handlers exposed to a patient with Hepatitis A.

Managment

Preexposure• VACCINATION:- Inactivated HAV Vaccine Parenteral

Indications for Hepatitis-A Vaccine:

• Persons with chronic liver disease (e.g. hepatitis B or C)• Homosexuals

• Travelers to highly endemic areas

• Drug users( drug addicts), particularly injection drug users

• Persons at occupational risk for infection

Acute liver failure is rare in hepatitis A (0.1%) and chronic infection does not occur. However, HAV infection in patients with chronic liver disease may cause serious or life-threatening disease. In adults, a cholestatic phase with elevated ALP levels may complicate infection. There is no role for antiviral drugs in the therapy of HAV infection.

Managment

Hepatitis E is caused by an RNA virus.The clinical presentation and management of hepatitis E are similar to that of hepatitis A. Hepatitis E differs from hepatitis A in that infection during pregnancy is associated with the development of acute liver failure, which has a high mortality. In acute infection, IgM antibodies to HEV are positive.

Hepatitis E infection

• Hepatitis E vs A• HEV HAV

• Fecal-oral transmission Yes Yes

• Transmission in family No Yes

• Distribution Developing countries Worldwide

• Ages infected Young adults All

• Subclinical infection Yes Yes

• Chronic infection No No

Hepatitis B is one of the most common causes of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma

Humans are the only source of infection

350–400 million people are chronic HBsAg carriers

Hepatitis B may cause an acute viral hepatitis; however, acute infection is often asymptomatic, The risk of progression to chronic liver disease depends on the source and timing of infection

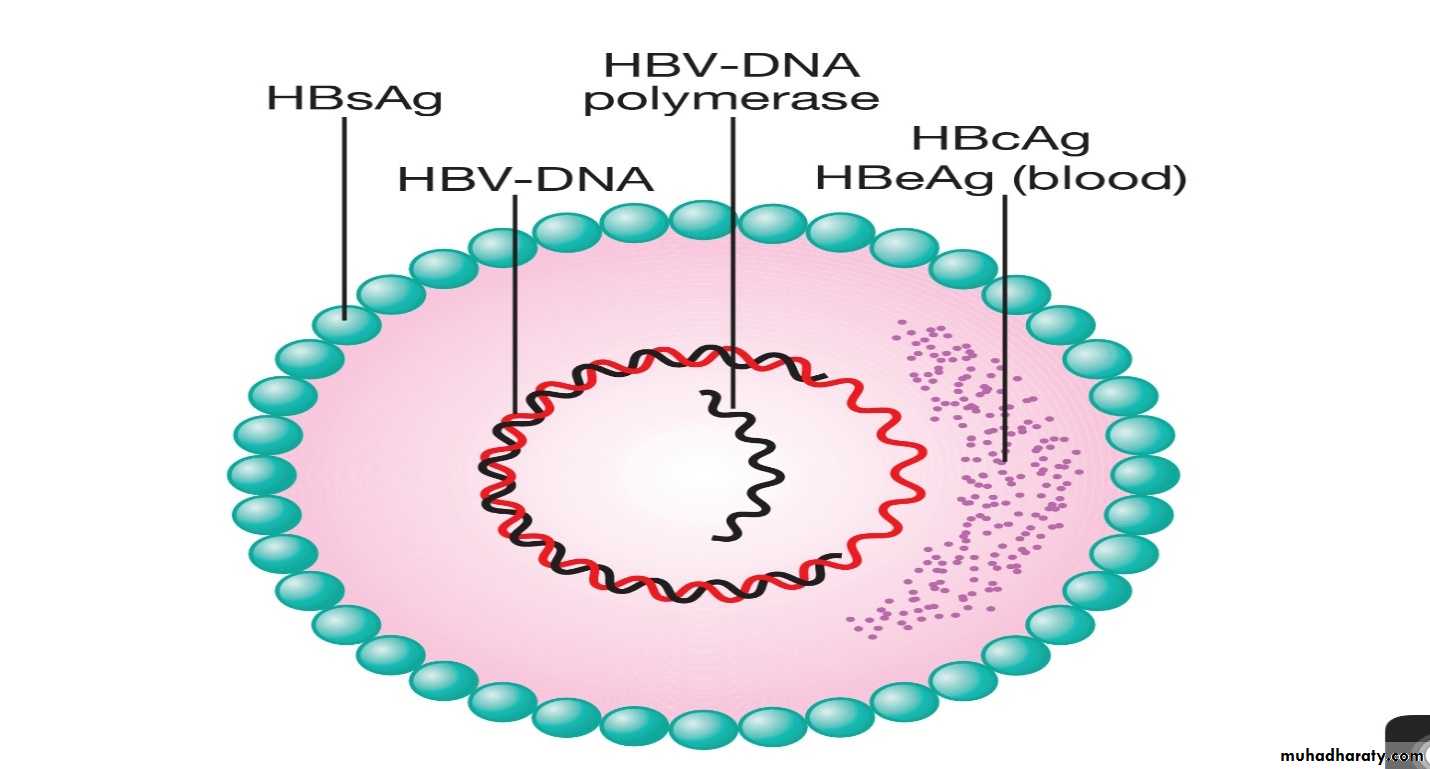

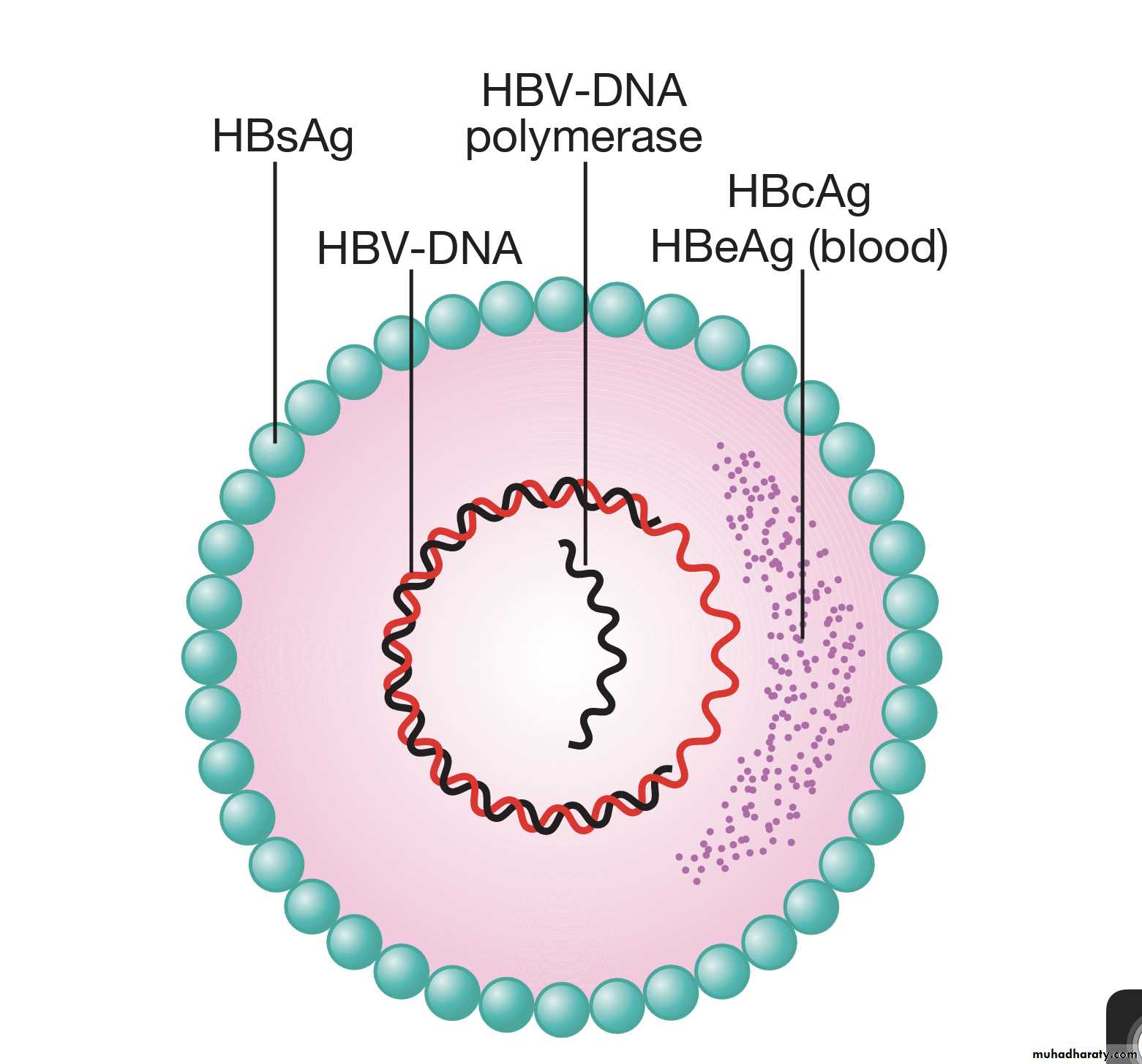

The Causative Agent:

. Hepatitis B virus (HBV)

. Double stranded DNA genome

. Enveloped

. Virus contains 3 important HBV antigens

• HBsAg: Surface antigen

• HBcAg:Core antigen

• HBeAg:e antigen

Hepatitis B infection

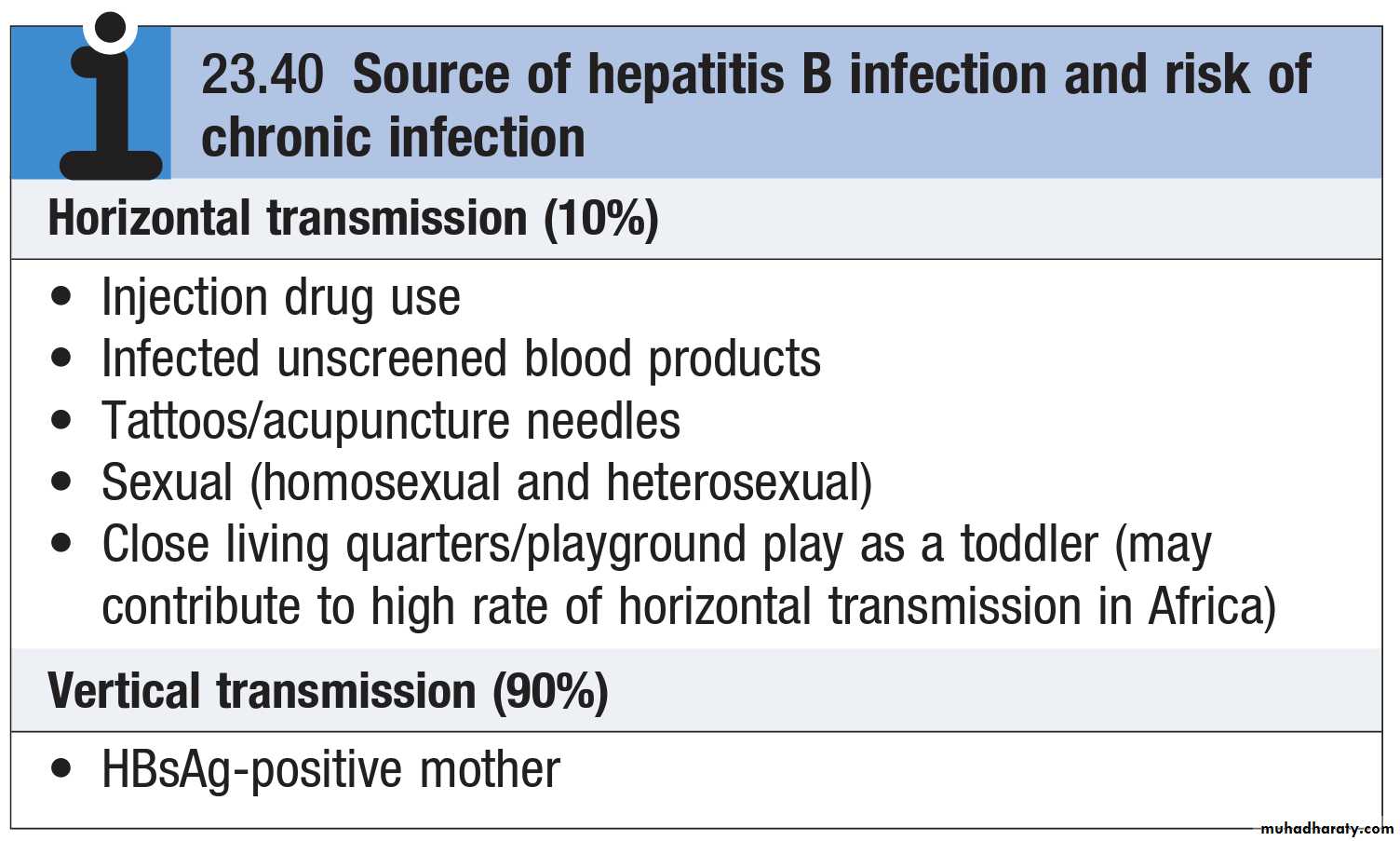

Source of infection

Hepatitis B is transmitted through exposure to body fluids containing the virus:• Perinatal is the most common cause of infection world wide and carries high risk of chronic infection.

• Sexual transmission.

• Parentral/percutaneous,

• blood / blood products, needle stick, injection drug use, tattooing and piercing with contaminated instruments, acupuncture.

• Non-sexual person-to-person contact, e.g., household contact, Shared toothbrushes, razors, and towels.

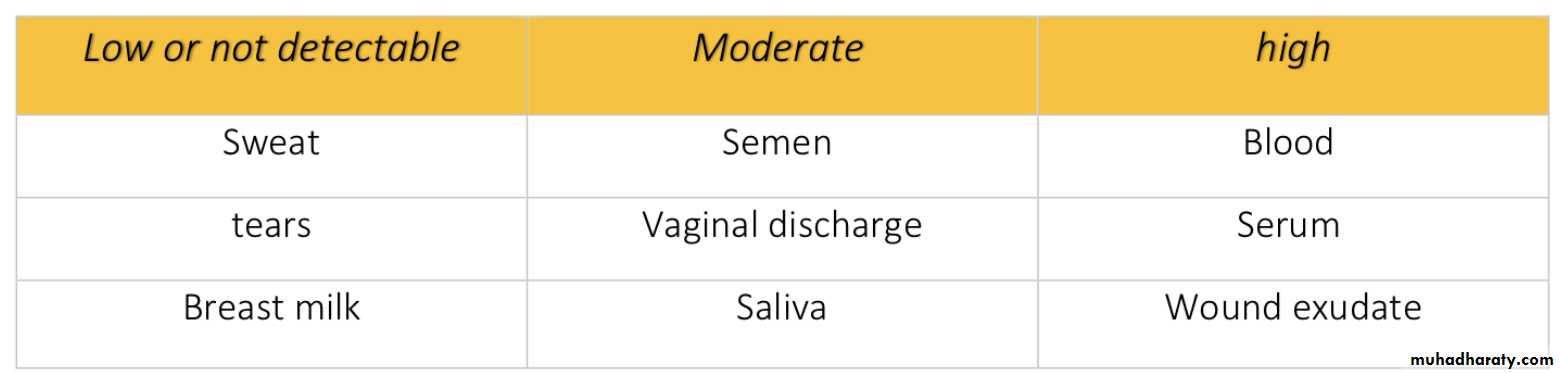

Concentration of Hepatitis B Virus in Various Body Fluids

Modes of Transmission:

• Similar to hepatitis A

• Symptomatic infection increases with the increase in age

• In children < 5 yrs: <10% develop clinical jaundice

• 5 yrs and above: 30%-50% develop clinical jaundice

The outcomes:

• Recovery from symptomatic & asymptomatic infection.

• Death from fulminant acute hepatitis.

• Chronic carrier, usually for life.

Clinical Features & outcomes

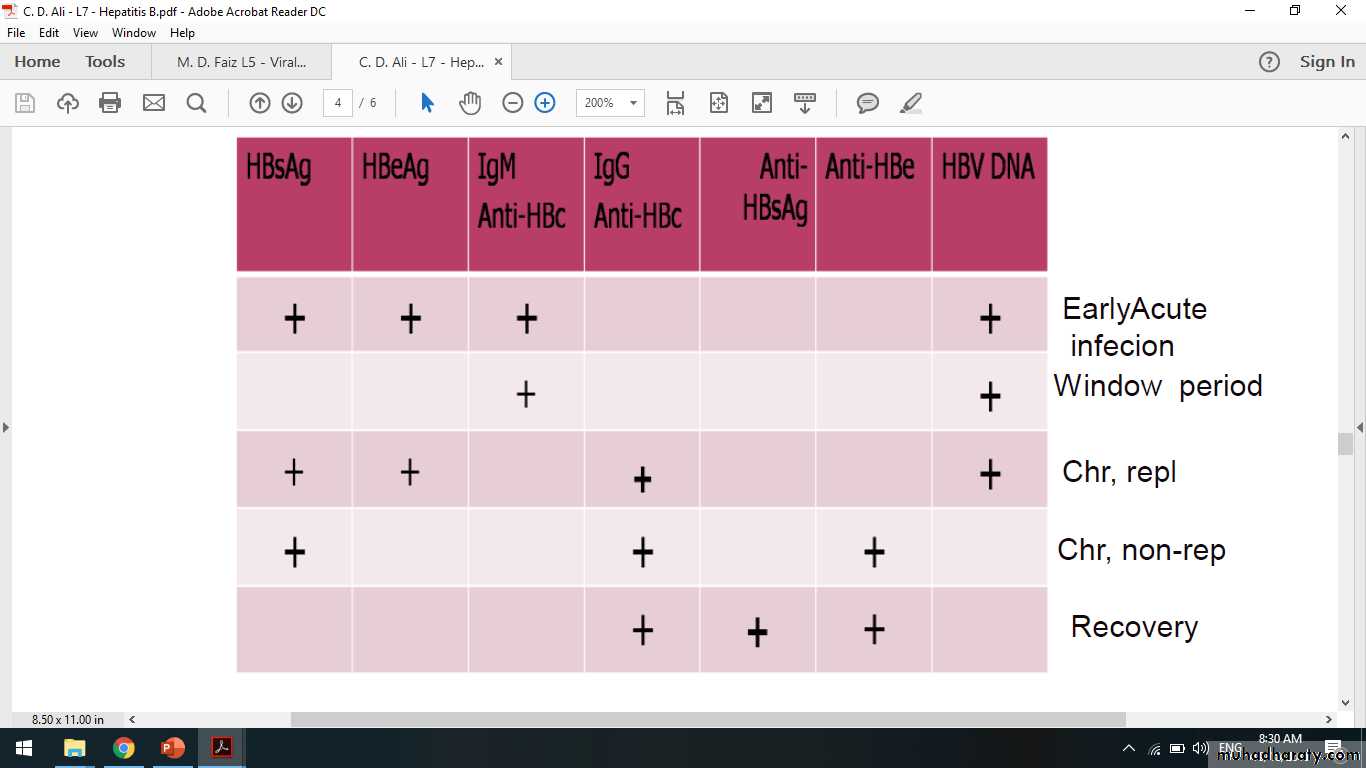

Abnormal liver function testSerological tests: many serological tests are used for the diagnosis of acute and chronic hepatitis B infection.

• HBsAg - used as a general marker of infection (acute and chronic infection).

• Anti-HBc IgM - marker of acute infection.

• Anti-HBc IgG – a marker of past or chronic infection.

• HBeAg - indicates active replication of virus and therefore infectiveness.

• Anti-Hbe – indicates that the virus no longer replicating. However, the patient can still be positive for HBsAg.

• Anti-HBs- used to indicate recovery and/or immunity to HBV infection.

• HBV-DNA - indicates active replication of virus, more accurate than HBeAg . Used mainly for monitoring response to therapy.

Diagnosis

Serological Markers for HBV Infection

Treatment is supportive, with monitoring for acute liver failure, which occurs in less than 1% of cases.Full recovery occurs in 90–95% of adults following acute HBV infection.

The remaining 5–10% develop a chronic hepatitis B infection that usually continues for life, although later recovery occasionally occurs.

Infection passing from mother to child at birth leads to chronic infection in the child in 90% of cases and recovery is rare.

Recovery from acute HBV infection occurs within 6 months and is characterised by the appearance of antibody to viral antigens.

Persistence of HBeAg beyond this time indicates chronic infection. Combined HBV and HDV infection causes more aggressive disease.

Management of acute hepatitis B

The goals of treatment are HBeAg seroconversion, reduction in HBV-DNA and normalisation of the LFTs.

The indication for treatment is a high viral load in the presence of active hepatitis, as demonstrated by elevated serum transaminases and/or histological evidence of inflammation and fibrosis.

The oral antiviral agents are more effective in reducing viral loads in patients with e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B than in those with e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B.

Most patients with chronic hepatitis B are asymptomatic and develop complications such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma only after many years. Cirrhosis develops in 15–20% of patients with chronic HBV over 5–20 years. This proportion is higher in those who are e antigen-positive.

Management of chronic hepatitis B

Two different types of drug are used to treat hepatitis B: direct-acting nucleoside/nucleotide analogues and pegylated interferon-alfa.

• Direct-acting nucleoside/nucleotide antiviral agents: One major concern is the selection of antiviral-resistant mutations with long-term treatment. This is particularly important with some of the older agents, such as lamivudine, as mutations induced by previous antiviral exposure may also induce resistance to newer agents. Entecavir and tenofovir are potent antivirals with a high barrier to genetic resistance, and so are the most appropriate first-line agents and the relapse is common if treatment is withdrawn.

• Interferon-alfa: this is most effective in patients with a low viral load and serum transaminases greater than twice the upper limit of normal, in whom it acts by augmenting a native immune response, Interferon is contraindicated in the presence of cirrhosis.

Liver transplantation

Historically, liver transplantation was contraindicated in hepatitis B because infection often recurred in the graft. However, the use of post-liver transplant prophylaxis with direct-acting antiviral agents and hepatitis B immunoglobulins has reduced the re-infection rate to 10% and increased 5-year survival to 80%, making transplantation an acceptable treatment option.

A recombinant hepatitis B vaccine containing HBsAg is available (Engerix) and is capable of producing active immunisation in 95% of normal individuals.

hyperimmune serum globulin prepared from blood containing anti-HBs. This should be given within 24 hours, or at most a week, of exposure to infected blood in circumstances likely to cause infection (e.g. needlestick injury, contamination of cuts or mucous membranes).

Neonates born to hepatitis B-infected mothers should be immunised at birth and given immunoglobulin. Hepatitis B serology should then be checked at 12 months of age.

Prevention:

People exposed to blood as a result of their occupation or of medical treatment; health care workers; recipients of blood products; haemodialysis patients & staff.

Household contacts & sexual partners of infected persons.

Homosexuals & sexually promiscuous

Injecting drug users (IDUs); drug addicts

Babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers.

Hepatitis B Risk groups

The hepatitis D virus (HDV) is an RNA-defective virus it requires HBV for replication and has the same sources and modes of spread.

It can infect individuals simultaneously with HBV, or can superinfect those who are already chronic carriers of HBV.

Simultaneous infections give rise to acute hepatitis, which is often severe but is limited by recovery from the HBV infection.

Infections in individuals who are chronic carriers of HBV can cause acute hepatitis with spontaneous recovery, and occasionally simultaneous cessation of the chronic HBV infection occurs.

Chronic infection with HBV and HDV can also occur, and this frequently causes rapidly progressive chronic hepatitis and eventually cirrhosis.

Hepatitis D (Delta virus)

Investigations:

HDV contains a single antigen to which infected individuals make an antibody (anti-HDV).

Delta antigen appears in the blood only transiently, and in practice diagnosis depends on detecting anti-HDV.

Management: Effective management of hepatitis B prevents hepatitis D.

Hepatitis D (Delta virus)

This is caused by an RNA flavivirus. Acute symptomatic infection with hepatitis C is rare. Most individuals are unaware of when they became infected and are only identified when they develop chronic liver disease. 80% of individuals exposed to the virus become chronically infected and late spontaneous viral clearance is rare.

Hepatitis C is the cause of what used to be known as ‘non-A, non-B hepatitis’. Hepatitis C infection is usually identified in asymptomatic individuals screened because they have risk factors for infection, such as previous injecting drug use, or have incidentally been found to have abnormal liver blood tests. Although most individuals remain asymptomatic until progression to cirrhosis occurs, fatigue can complicate chronic infection and is unrelated to the degree of liver damage.

Hepatitis C infection

1. Intravenous drug misuse (95% of new cases in the UK).

2. Unscreened blood products.3. Vertical transmission (3% risk).

4. Needlestick injury (3% risk).

5. Iatrogenic parenteral transmission (i.e. contaminated vaccination needles).

6. Sharing toothbrushes/razors.

Risk factors for the acquisition of chronic hepatitis C infection

a) Serology and virology: The HCV protein contains several antigens that give rise to antibodies in an infected person. It may take 6–12 weeks for antibodies to appear in the blood following acute infection such as a needlestick injury. In these cases, hepatitis C RNA can be identified in the blood as early as 2–4 weeks after infection. Active infection is confirmed by the presence of serum hepatitis C RNA in anyone who is antibody-positive. Anti-HCV antibodies persist in serum even after viral clearance, whether spontaneous or post-treatment.b) Molecular analysis: There are six common viral genotypes. Genotype 1 is most common in northern Europe.

c) Liver function tests: LFTs may be normal or show fluctuating serum transaminases between 50 and 200 U/L. Jaundice is rare and only usually appears in end-stage cirrhosis.

d) Liver histology: Serum transaminase levels in hepatitis C are a poor predictor of the degree of liver fibrosis and so a liver biopsy is often required to stage the degree of liver damage.

Investigations:

The aim of treatment is to eradicate infection.

The treatment of choice new HCV DAAs (direct acting antiviral agent) have been licensed in the last guide lines.

Old one use dual therapy pegylated interferon-alfa given as a weekly subcutaneous injection, together with oral ribavirin, a synthetic nucleotide analogue. and cure is defined as loss of virus from serum 6 months after completing therapy. (12 months’ treatment for genotype 1 results in a 40% SVR(sustained virological response), whereas 6 months’ treatment for genotype 2 or 3 leads to an SVR in > 70%).

The recent availability of triple therapy with the addition of protease inhibitors such as telaprevir and boceprevir to standard pegylated interferon/ribavirin has provided a significant advance in therapy.

Liver transplantation should be considered when complications of cirrhosis occur, such as diuretic resistant ascites. Unfortunately, hepatitis C almost always recurs in the transplanted liver and up to 15% of patients will develop cirrhosis in the liver graft within 5 years of transplantation.

Managment

Pyogenic liver abscessPyogenic liver abscesses are uncommon but important because they are potentially curable, carry significant morbidity and mortality if untreated, and are easily overlooked. The mortality of liver abscesses is 20–40%; failure to make the diagnosis is the most common cause of death.

Causes of pyogenic liver abscesses

1. Biliary obstruction (cholangitis)

2. Haematogenous

-Portal vein (mesenteric infections).

-Hepatic artery (bacteraemia).

3. Direct extension.

4. Trauma (Penetrating or non-penetrating)

5. Infection of liver tumour or cyst.

Clinical features: Patients are generally ill with fever, and sometimes rigors and weight loss. Abdominal pain is the most common symptom and is usually in the right upper quadrant, sometimes with radiation to the right shoulder. The pain may be pleuritic in nature. Tender hepatomegaly is found in more than 50% of patients. Mild jaundice may be present, becoming severe if large abscesses cause biliary obstruction.

Liver abscess

Liver imaging .

Needle aspiration under ultrasound guidance.

A leukocytosis .

plasma ALP is raised.

serum albumin is often low.

The chest X-ray may show a raised right diaphragm and lung collapse, or an effusion at the base of the right lung .

Blood cultures are positive in 50–80% .

colonoscopy to exclude colorectal carcinoma.

Treatment: prolonged antibiotic therapy and drainage of the abscess. treatment should be commenced with a combination of antibiotics such as ampicillin, gentamicin and metronidazole.

Investigations

Hydatid cysts are caused by Echinococcus granulosus infection. They have an outer layer derived from the host, an intermediate laminated layer and an inner germinal layer. They can be single or multiple. Chronic cysts become calcified. The cysts maybe asymptomatic but may present with abdominal pain or a mass.

Rupture or secondary infection of cysts can occur, and a communication with the intrahepatic biliary tree can then result, with associated biliary obstruction and jaundice.

Investigation:

Peripheral blood eosinophilia is present in 20% of casesX-rays may show calcification

CT reliably shows the cyst(s)

(ELISA) has 90% sensitivity for hepatic hydatid cysts

Hydatid cysts

All patients should be treated medically with albendazole or mebendazole prior to definitive therapy.

In the absence of communications with the biliary tree, treatment consists of percutaneous aspiration of the cyst followed by the injection of 100% ethanol into the cysts and then re- aspiration of the cyst contents (PAIR).

Where there is communication between the cyst and biliary b system, surgical removal of the intact cyst is the preferred treatment.

Treatment

Amoebic liver abscesses are caused by Entamoeba histolytica infection. Up to 50% of cases do not have a previous history of intestinal disease.

Abscesses are usually large, single and located in the right lobe; multiple abscesses may occur in advanced disease.

Fever and abdominal pain or swelling are the most common symptoms. There may not be associated diarrhoea.

Early symptoms may be local discomfort only and malaise; later, a swinging temperature and sweating may develop, usually without marked systemic symptoms or associated cardiovascular signs.

An enlarged, tender liver, cough and pain in the right shoulder are characteristic, but symptoms may remain vague and signs minimal.

Amoebic liver abscess

The stool and any exudate should be examined at once under the microscope for motile trophozoites containing red blood cells.

Sigmoidoscopy may reveal typical flask-shaped ulcers.

neutrophil leukocytosis.

raised right hemidiaphragm on chest X-ray.

ultrasonic scanning.

Aspirated pus from an amoebic abscess has the characteristic anchovy sauce or chocolate-brown appearance but only rarely contains free amoebae

Serum antibodies (carries 99% sensitivity and over 90% specificity).

DNA detection by PCR.

Investigation

Intestinal and early hepatic amoebiasis responds quickly to oral metronidazole (800 mg 3 times daily for 5–10 days).

or other long-acting nitroimidazoles like tinidazole or ornidazole (both in doses of 2 g daily for 3 days). Nitazoxanide (500 mg twice daily for 3 days) is an alternative drug.

Either diloxanide furoate or paromomycin, in doses of 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 10 days after treatment, should be given to eliminate luminal cysts.

aspiration is required If a liver abscess is large or threatens to burst, or if the response to chemotherapy is not prompt, and is repeated if necessary.

Rupture of an abscess into the pleural cavity, pericardial sac or peritoneal cavity necessitates immediate aspiration or surgical drainage.

Small serous effusions resolve without drainage.

Management

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

is an umbrella term for a range of liver conditions affecting people who drink little to no alcohol. As the name implies, the main characteristic of NAFLD is too much fat stored in liver cells.it is the most common form of chronic liver disease, affecting about one-quarter of the population.

Some individuals with NAFLD can develop nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), an aggressive form of fatty liver disease, which is marked by liver inflammation and may progress to advanced scarring (cirrhosis) and liver failure. This damage is similar to the damage caused by heavy alcohol use.

Metabolic hepatitis

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

Symptoms:NAFLD usually causes no signs and symptoms. When it does, they may include:

• Fatigue

• Pain or discomfort in the upper right abdomen

Possible signs and symptoms of NASH and advanced scarring (cirrhosis) include:

• Abdominal swelling (ascites)• Enlarged blood vessels just beneath the skin’s surface.

• Enlarged spleen

• Red palms

• Yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice)

Metabolic hepatitis

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

Causes:

Experts don't know exactly why some people accumulate fat in the liver while others do not. Similarly, there is limited understanding of why some fatty livers develop inflammation that progresses to cirrhosis.

NAFLD and NASH are both linked to the following:

• Overweight or obesity

• Insulin resistance.

• High blood sugar (hyperglycemia), indicating prediabetes or type 2 diabetes

• High levels of fats, particularly triglycerides.

Metabolic hepatitis

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

PreventionTo reduce your risk of NAFLD:

• Choose a healthy diet.

• Maintain a healthy weight.

• Exercise.

Metabolic hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitisExcessive alcohol consumption is a significant cause of hepatitis and is the most common cause of cirrhosis in the U.S. Alcoholic hepatitis is within the spectrum of alcoholic liver disease. This ranges in order of severity and reversibility from alcoholic steatosis (least severe, most reversible), alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer (most severe, least reversible).

Hepatitis usually develops over years-long exposure to alcohol, occurring in 10 to 20% of alcoholics.

Metabolic hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitisThe most important risk factors for the development of alcoholic hepatitis are quantity and duration of alcohol intake. Long-term alcohol intake in excess of 80 grams of alcohol a day in men and 40 grams a day in women is associated with development of alcoholic hepatitis .

Alcoholic hepatitis can vary from asymptomatic hepatomegaly to symptoms of acute or chronic hepatitis to liver failure.

Metabolic hepatitis

Toxic and drug-induced hepatitisMany chemical agents, including medications, industrial toxins, and herbal and dietary supplements, can cause hepatitis. The spectrum of drug-induced liver injury varies from acute hepatitis to chronic hepatitis to acute liver failure. Toxins and medications can cause liver injury through a variety of mechanisms, including direct cell damage, disruption of cell metabolism, and causing structural changes.

Some drugs such as paracetamol exhibit predictable dose-dependent liver damage while others such as isoniazid cause idiosyncratic and unpredictable reactions that vary among individuals.

Many types of drugs can cause liver injury, including the analgesic paracetamol; antibiotics such as isoniazid, nitrofurantoin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, erythromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; anticonvulsants; statins; steroids and highly active anti-retroviral therapy.

Of these, amoxicillin-clavulanate is the most common cause of drug-induced liver injury, and paracetamol toxicity the most common cause of acute liver failure in the United States and Europe.

Metabolic hepatitis

is a disease of immune-mediated liver injury characterised by the presence of serum antibodies and peripheral blood T lymphocytes reactive with self-proteins, a strong association with other autoimmune diseases and high levels of serum immunoglobulins – in particular, elevation of IgG.Although most commonly seen in women, particularly in the second and third decades of life, it can develop in either sex at any age.

The reasons for the breakdown in immune tolerance in autoimmune hepatitis remain unclear,

although cross-reactivity with viruses such as HAV and EBV in immunogenetically susceptible individuals (typically those with human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR3 and DR4.

Autoimmune hepatitis

Clinical featuresThe onset is usually insidious, with fatigue, anorexia and jaundice. In about one-quarter of patients, the onset is acute, resembling viral hepatitis, but resolution does not occur. This acute presentation can lead to extensive liver necrosis and liver failure.

Other features include fever, arthralgia, vitiligo and epistaxis. Amenorrhoea can occur. Jaundice is mild to moderate or occasionally absent, but signs of chronic liver disease, especially spider naevi and hepatosplenomegaly, can be present.

Associated autoimmune disease, such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis or rheumatoid arthritis, is often present and can modulate the clinical presentation.

Autoimmune hepatitis

Serological tests for autoantibodies are often positive.Anti nuclear antibody(ANA).

Anti-microsomal antibodies (anti-LKM) occur particularly in children and adolescents.

Elevated serum IgG levels.

liver biopsy.

Management

Treatment with corticosteroids is life-saving in autoimmune hepatitis, particularly during exacerbations of active and symptomatic disease. Initially, prednisolone 40 mg/day is given orally; the dose is then gradually reduced as the patient and LFTs improve.

Maintenance therapy should only be instituted once LFTs are normal (as well as IgG if elevated).

Investigations

Genetic causes of hepatitis include alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, hemochromatosis, and Wilson's disease.

In alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, a co-dominant mutation in the gene for alpha-1-antitrypsin results in the abnormal accumulation of the protein within liver cells, leading to liver disease.

Hemochromatosis and Wilson's disease are both autosomal recessive diseases involving abnormal storage of minerals.

In hemochromatosis, excess amounts of iron accumulate in multiple body sites, including the liver, which can lead to cirrhosis.

In Wilson's disease, excess amounts of copper accumulate in the liver and brain, causing cirrhosis and dementia.

Genetic

Ischemic hepatitis (also known as shock liver) results from reduced blood flow to the liver as in shock, heart failure, or vascular insufficiency.The condition is most often associated with heart failure but can also be caused by shock or sepsis.

Blood testing of a person with ischemic hepatitis will show very high levels of transaminase enzymes (AST and ALT).

The condition usually resolves if the underlying cause is treated successfully. Ischemic hepatitis rarely causes permanent liver damage.

Ischemic hepatitis

Hepatitis can also occur in neonates and is attributable to a variety of causes, some of which are not typically seen in adults. Congenital or perinatal infection with the hepatitis viruses, toxoplasma, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and syphilis can cause neonatal hepatitis.Structural abnormalities such as biliary atresia and choledochal cysts can lead to cholestatic liver injury leading to neonatal hepatitis.

Metabolic diseases such as glycogen storage disorders and lysosomal storage disorders are also implicated.

Neonatal hepatitis can be idiopathic, and in such cases, biopsy often shows large multinucleated cells in the liver tissue. This disease is termed giant cell hepatitis and may be associated with viral infection, autoimmune disorders, and drug toxicity.

Neonatal hepatitis