•leukaemias

The leukemias are agroup of disorders

charactrized by the accumulation of primitive

cells which take up more and more marrow

space at the expense of the normal

haematopoietic elements. Eventually, this

proliferation spills into the blood.

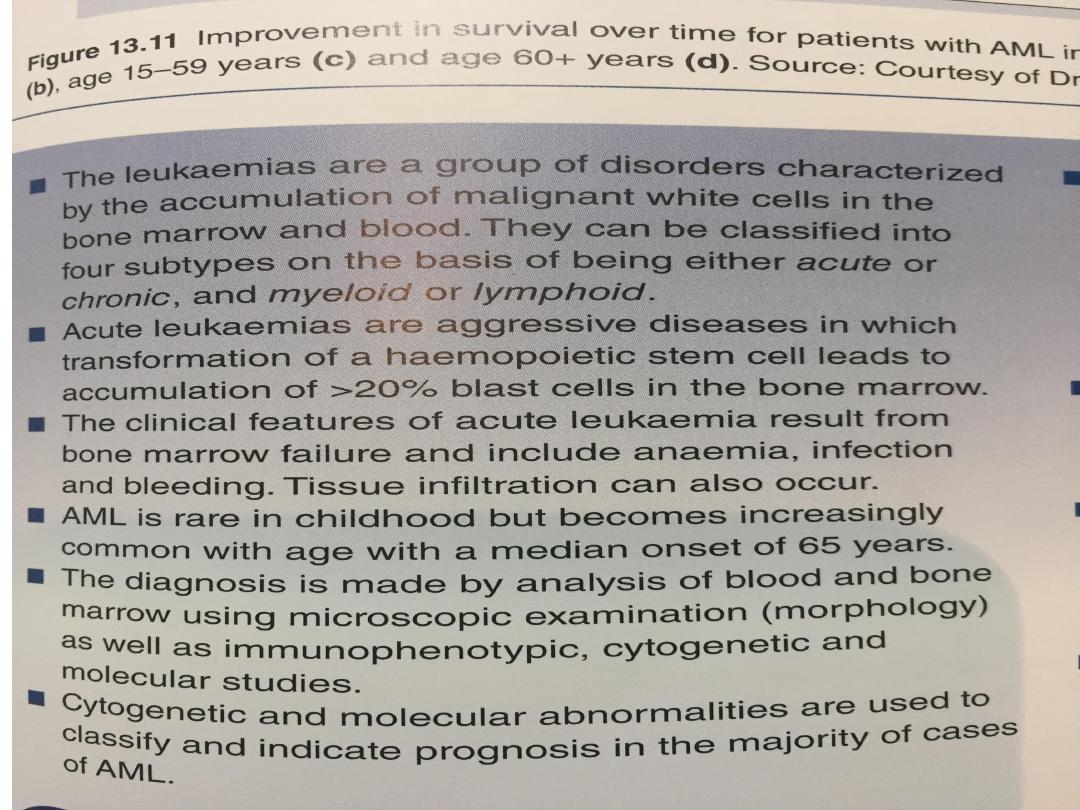

•Terminology and classification

Leukaemias are traditionally classified into four

main groups:

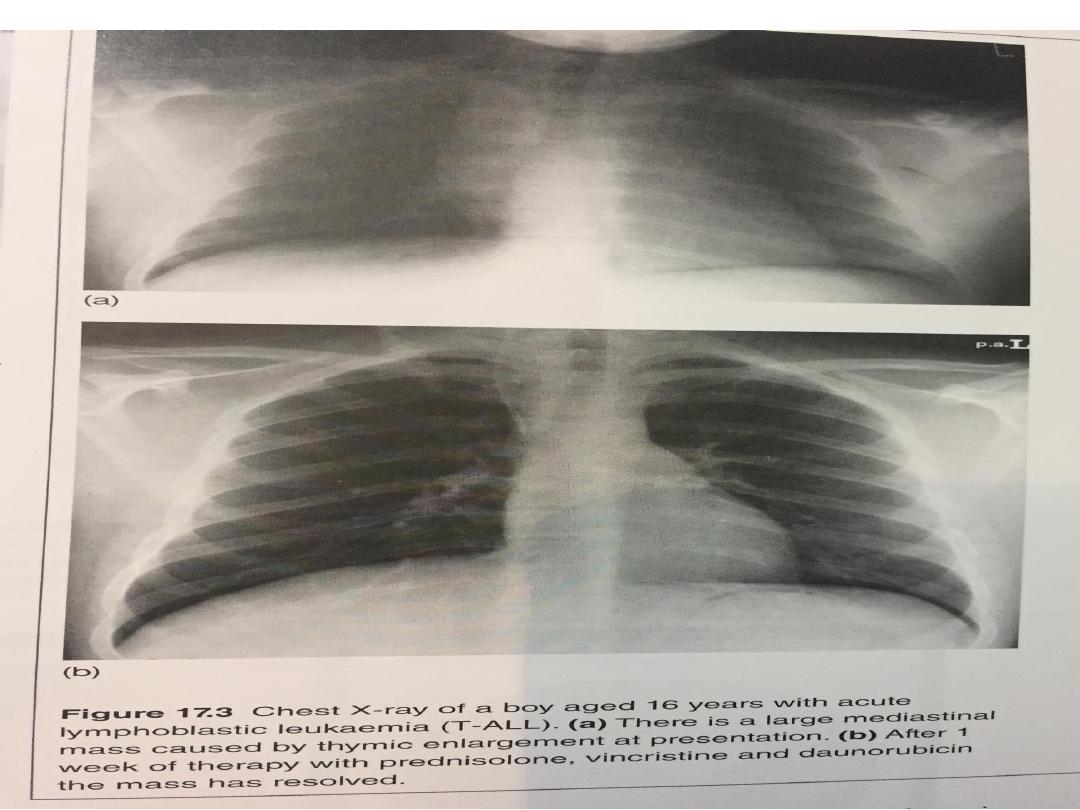

• acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)

• acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)

• chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)

• chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML).

•Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is about

four times more common than acute

lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) in adults.

•In children, the proportions are reversed,

the lymphoblastic variety being more

common.

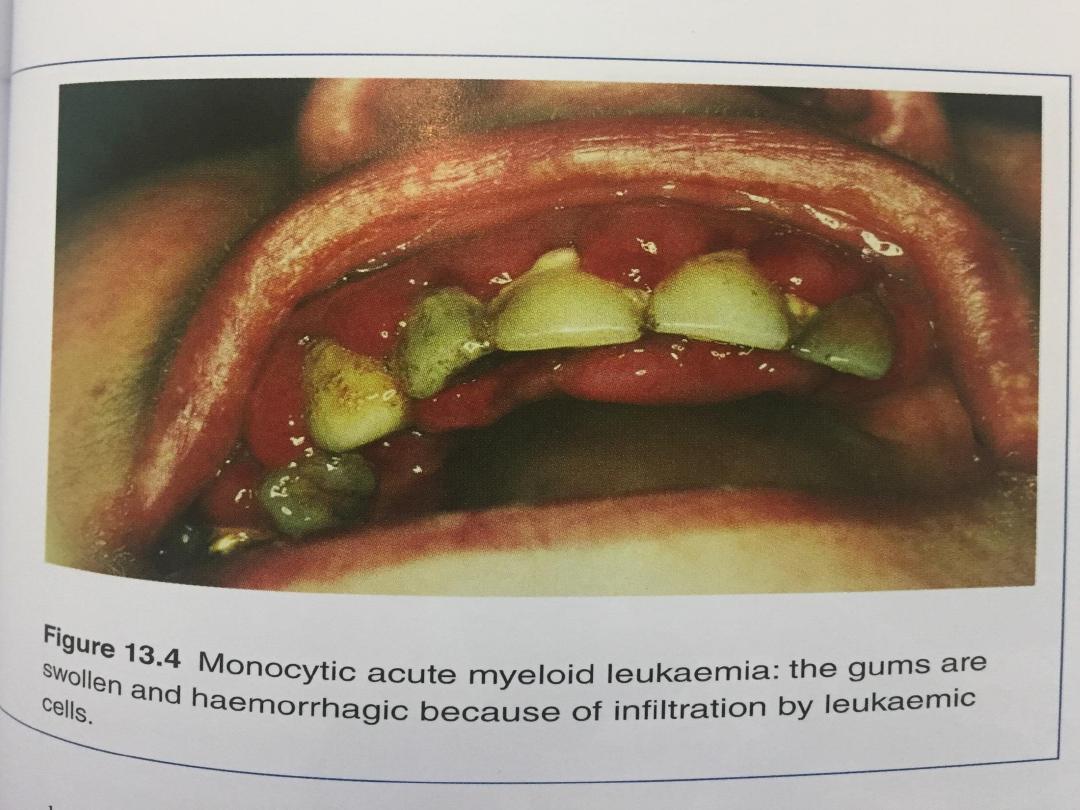

•The clinical features are usually those of

bone marrow failure.

Risk factors for leukaemia

1. Ionising radiation

• After atomic bombing of Japanese cities

(myeloid leukaemia)

• Radiotherapy for ankylosing spondylitis

• Diagnostic X-rays of the fetus in pregnancy

2. Cytotoxic drugs

• Especially alkylating agents (myeloid

leukaemia, usually after a latent period of

several years)

• Industrial exposure to benzene

3. Retroviruses

• One rare form of T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma appears to

be associated with a retrovirus similar to the viruses

causing leukaemia in cats and cattle

4. Genetic

• Identical twin of patients with leukaemia

• Down’s syndrome and certain other genetic disorders

5.Immunological

• Immune deficiency states (e.g.

hypogammaglobulinaemia)

• The diagnosis of leukaemia is usually suspected from an

abnormal blood count, often a raised white count, and is

confirmed by examination of the bone marrow.

• This includes the morphology of the abnormal cells,

analysis of cell surface markers (immunophenotyping),

clone-specific chromosome abnormalities and molecular

changes.

• In acute leukaemia, there is proliferation of primitive

stem cells, leading to an accumulation of blasts,

predominantly in the bone marrow, which causes bone

marrow failure.

• In chronic leukaemia, the malignant clone is able to

differentiate, resulting in an accumulation of more

mature cells.

• Lymphocytic and lymphoblastic cells are those derived

from the lymphoid stem cell (B cells and T cells).

Myeloid refers to the other lineages: that is, precursors

of red cells, granulocytes, monocytes and platelets

• The diagnosis of leukaemia is usually suspected from an

abnormal blood , often a raised white count, and is

confirmed by examination of the bone marrow.

• This includes the morphology of the abnormal cells,

analysis of cell surface markers (immunophenotyping),

clone-specific chromosome abnormalities and molecular

changes.

• These results are incorporated in the World Health

Organization (WHO) classification of tumours of

haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues

WHO classification of acute leukaemia

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) with

recurrent genetic abnormalities

1. AML with t(8;21)

2. AML with eosinophilia inv(16) or t(16;16)

3. Acute promyelocytic leukaemia t(15;17)

4. AML with t(9;11)(p22;q23)

5. AML with t(6;9)(p23;q34)

6. AML with inv(3)(q21q26.2) or

t(3;3)(q21;q26.2)

• Acute myeloid leukaemia with myelodysplasia-

related changes

• e.g. Following a myelodysplastic syndrome

Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms

• e.g. Alkylating agent or topoisomerase II inhibitor

Myeloid sarcoma

Myeloid proliferations related to Down’s syndrome

• Acute myeloid leukaemia not otherwise specified

• e.g. AML with or without differentiation, acute

myelomonocytic leukaemia, erythroleukaemia,

megakaryoblastic leukaemia, myeloid sarcoma

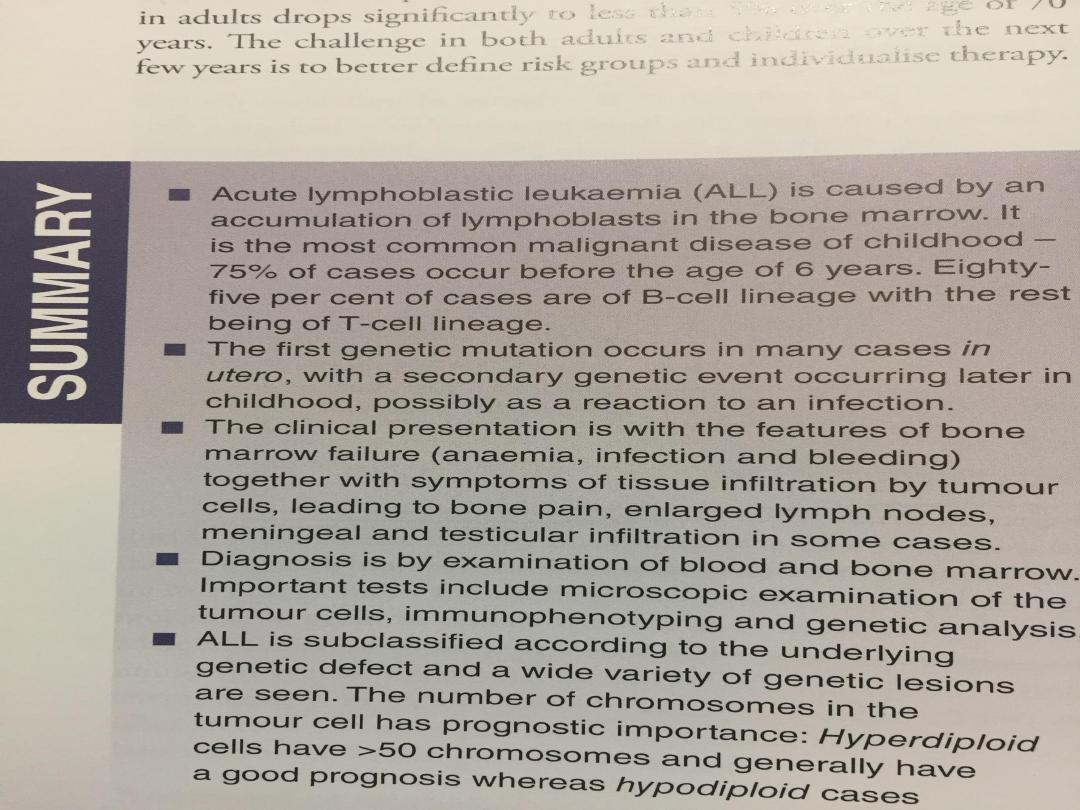

• Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)

Precursor B ALL

Precursor T ALL

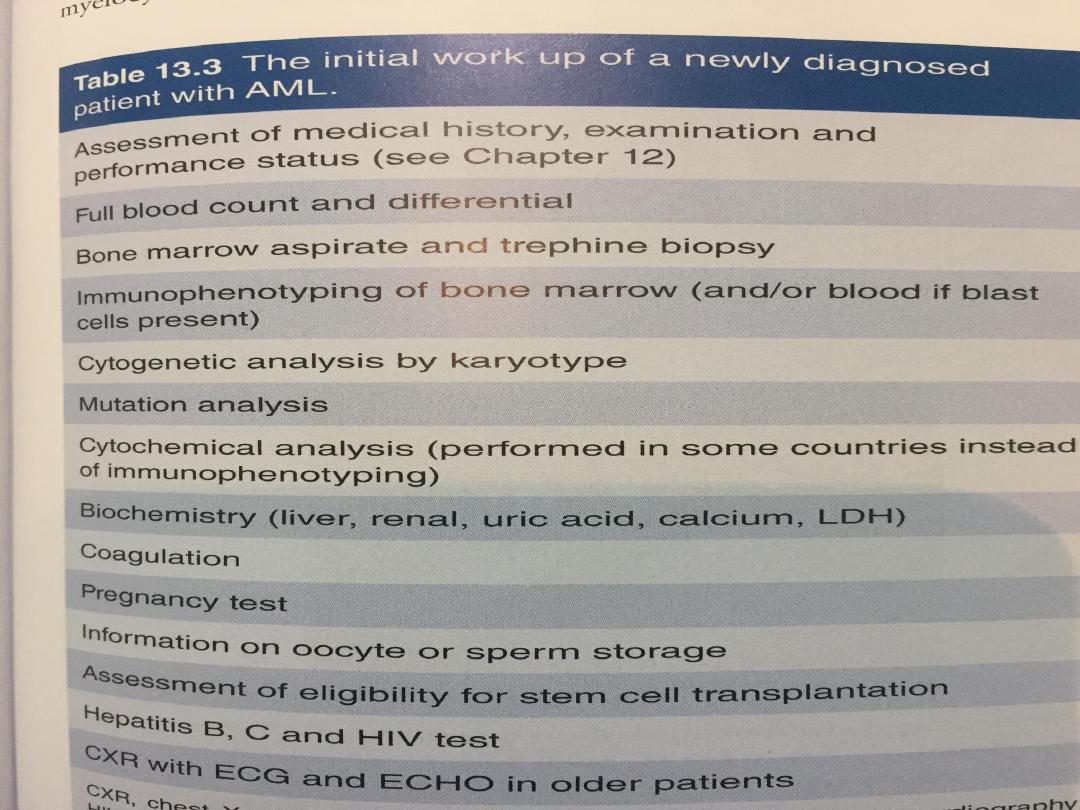

Investigations

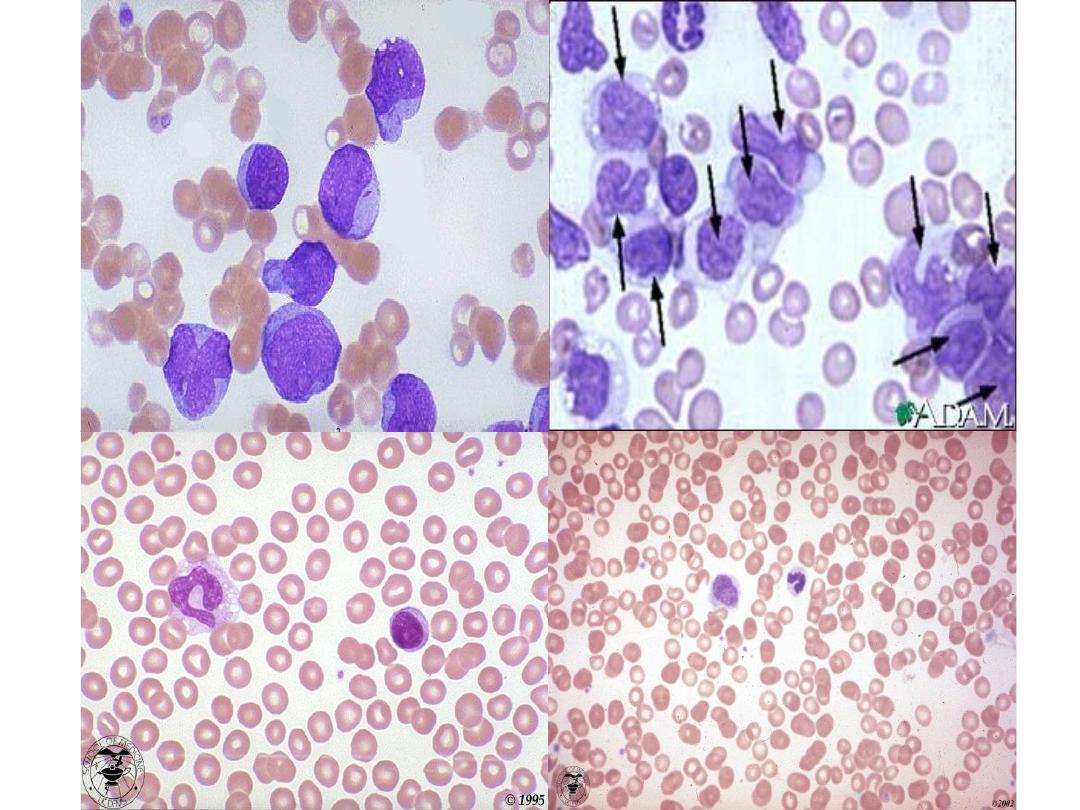

• Blood examination usually shows anaemia with a normal or

raised MCV. The leucocyte count may vary from as low as 1

×

109/L to as high as 500 × 109/L or more.

In the majority of patients, the count is below 100 × 109/L.

Severe thrombocytopenia is usual but not invariable.

• Frequently, blast cells are seen in the blood film but

sometimes blast cells may be infrequent or absent.

A bone marrow examination will confirm the diagnosis.

• The bone marrow is usually hypercellular, with replacement

of normal elements by leukaemic blast cells in varying

degrees (but more than 20% of the cells) .

• The presence of Auer rods in the cytoplasm of blast cells

indicates a myeloblastic type of leukaemia.

Classification and prognosis are determined by

immunophenotyping, chromosome and molecular analysis.

V1.0

V1.0

V1.0

Signs and Symptoms

• Fatigue

• Shortness of breath on exertion

• Easy bruising

• Petechiae

• Bleeding in the nose or from the gums

• Prolonged bleeding from minor cuts

• Recurrent minor infections or poor healing of minor cuts

• Loss of appetite or weight loss

• Mild fever

V1.0

V1.0

•Rudolf Virchow was born in

1821 in Poland. In 1843 he

graduated from Medical

College and in 1845 he

published his first paper on

leukemia. He had conducted

an autopsy and based on the

pathology called the disease

leukemia which in Greek

means leukos (white) aima (bl

ood). This work inspired him

to continue teaching

pathological anatomy.

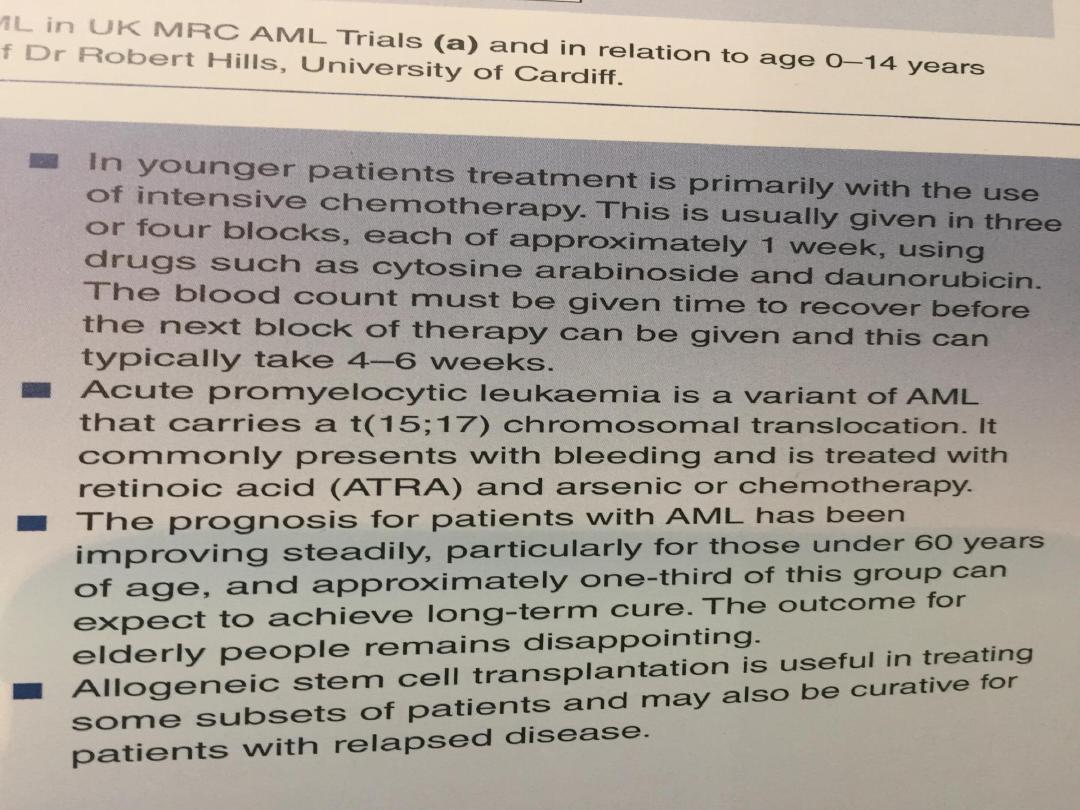

Management

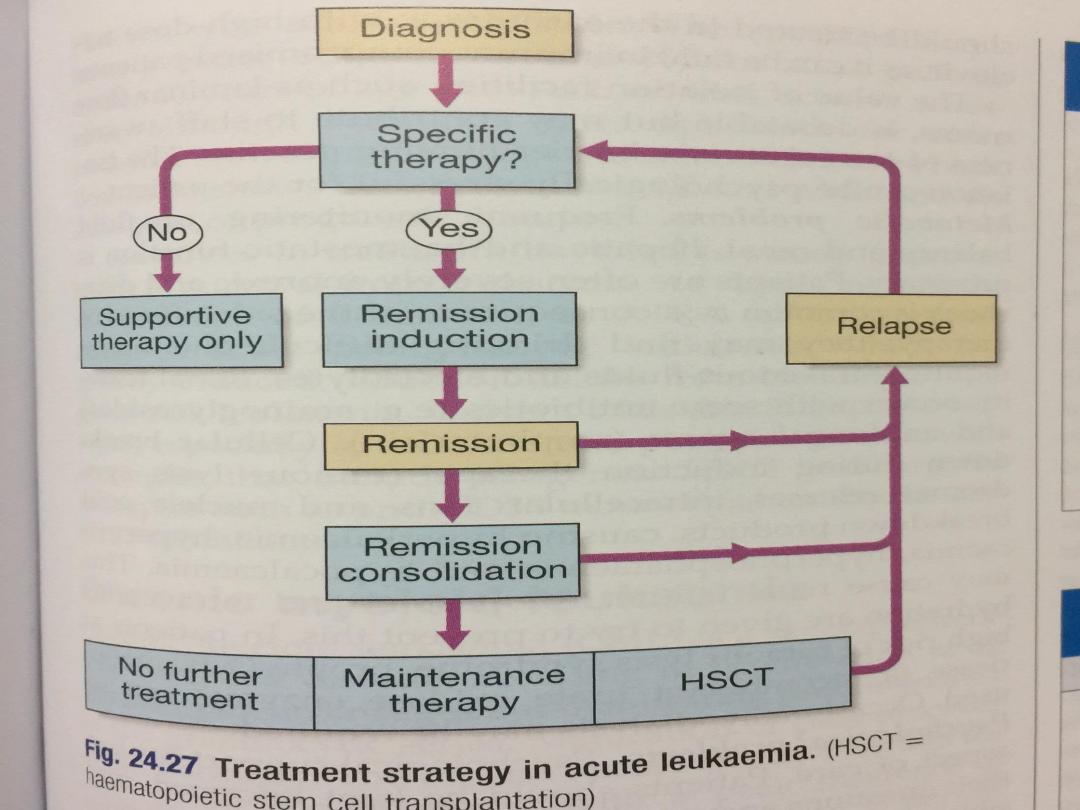

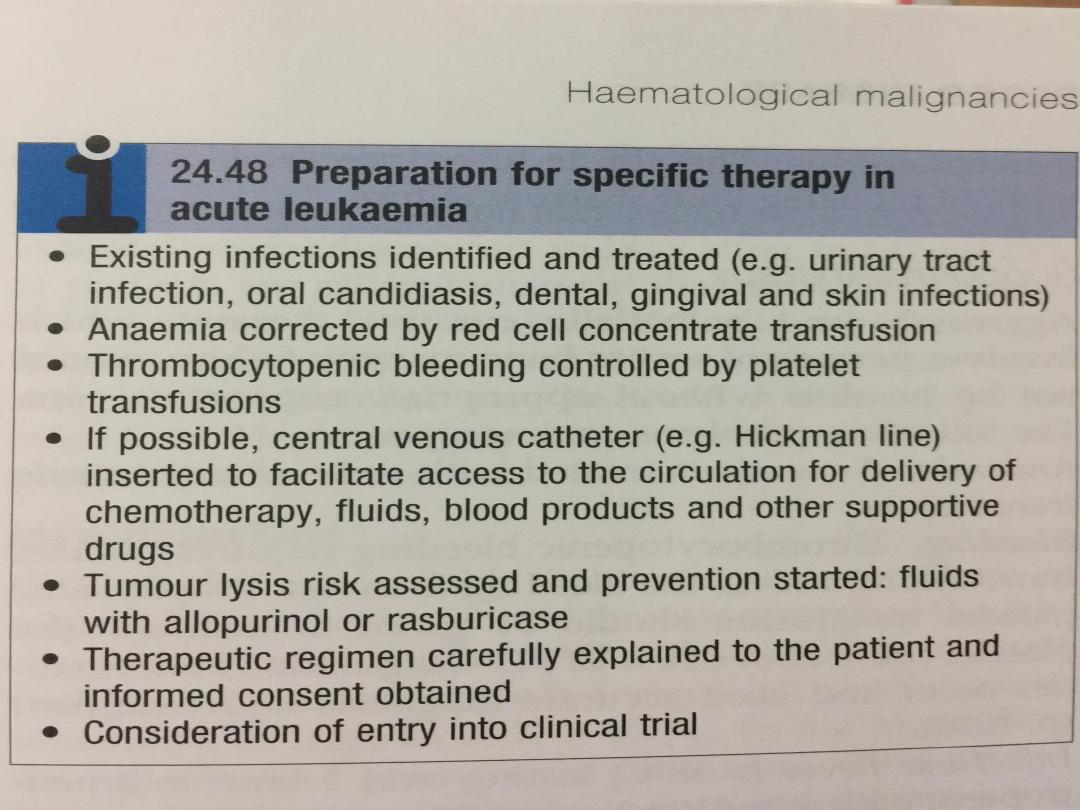

• The first decision must be whether or not to give specific treatment.

This is generally aggressive, has numerous side-effects, and may

not be appropriate for the very elderly or patients with serious

comorbidities In these patients, supportive treatment can effect

considerable improvement in well-being.

• The aim of treatment is to destroy the leukaemic clone of cells

without destroying the residual normal stem cell compartment from

which repopulation of the haematopoietic tissues will occur.

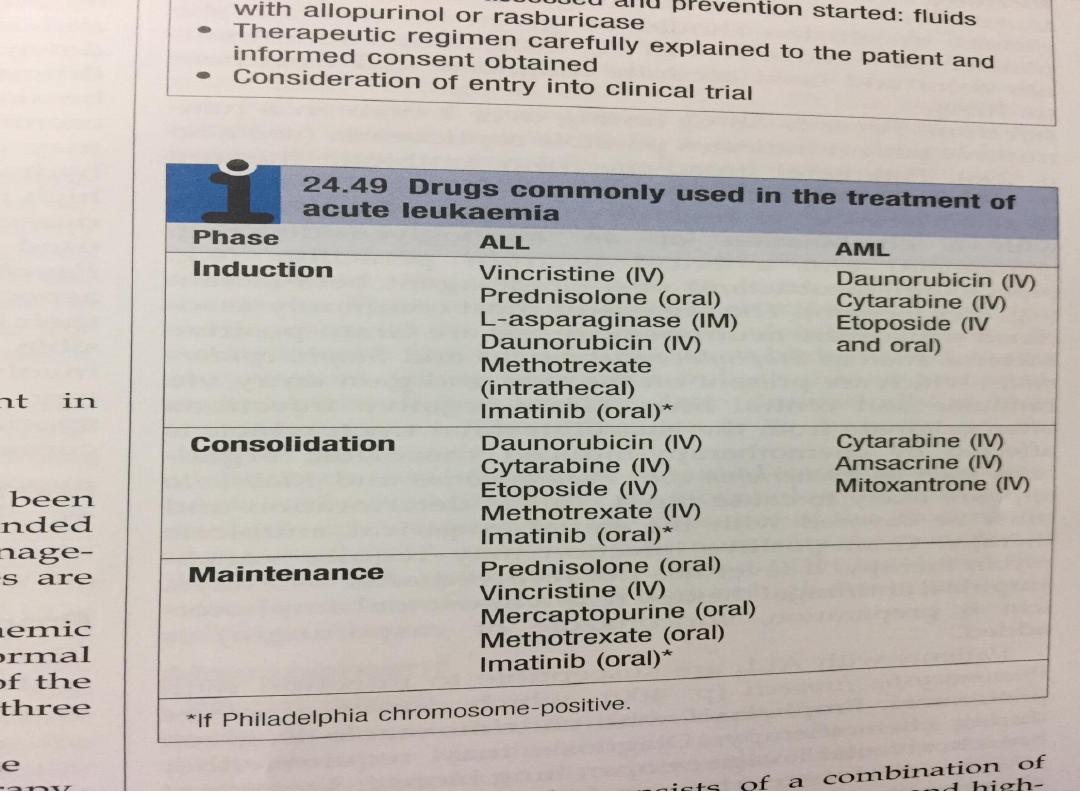

• There are three phases:

V1.0

A. Remission induction. In this phase, the bulk of the

tumour is destroyed by combination chemotherapy. The

patient goes through a period of severe bone marrow

hypoplasia, requiring intensive support and inpatient

care from a specially trained multidisciplinary team.

B. Remission consolidation. If remission has been

achieved, residual disease is attacked by therapy during

the consolidation phase. This consists of a number of

courses of chemotherapy, again resulting in periods of

marrow hypoplasia. In poor-prognosis leukaemia, this

may include haematopoietic stem cell transplantation

C. Remission maintenance. If the patient is still in

remission after the consolidation phase for ALL, a period

of maintenance therapy is given, with the individual as

an outpatient and treatment consisting of a repeating

cycle of drug administration. This may extend for up to 3

years if relapse does not occur..

• In patients with ALL, it is necessary to give prophylactic

treatment to the central nervous system, as this is a

sanctuary site where standard therapy does not

penetrate

• This usually consists of a combination of cranial

irradiation, intrathecal chemotherapy and highdose

methotrexate, which crosses the blood–brain barrier.

Thereafter, specific therapy is discontinued and the

patient observed.

• In some patients, alternative palliative chemotherapy,

not designed to achieve remission, may be used to curb

excessive leucocyte proliferation. Drugs used for this

purpose include hydroxycarbamide and mercaptopurine.

The aim is to reduce the blast count without inducing

bone marrow failure.

V1.0

Supportive therapy

• Aggressive and potentially curative therapy, which

involves periods of severe bone marrow failure, would

not be possible without appropriate supportive care.

The following problems commonly arise.

• Anemia. Anaemia is treated with red cell concentrate

transfusions.

• Bleeding. Thrombocytopenic bleeding requires platelet

transfusions, unless the bleeding is trivial. Prophylactic

platelet transfusion should be given to maintain the

platelet count above 10 × 109/L. Coagulation

abnormalities occur and need accurate diagnosis and

treatment

• Infection. Fever (> 38°C) lasting over 1 hour in a neutropenic

patient indicates possible septicaemia Parenteral broad-spectrum

antibiotic therapy is essential. Empirical therapy is given according

to local bacteriological resistance patterns:

• for example, with a combination of an aminoglycoside (e.g.

gentamicin) and a broad-spectrum penicillin (e.g.

piperacillin/tazobactam) or a single-agent beta-lactam (e.g.

meropenem

• The organisms most commonly associated with severe neutropenic

sepsis are Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus

and Staph. epidermidis, which are present on the skin and gain

entry via cannulae and central lines.

• Gram-negative infections often originate from the gastrointestinal

tract, which is affected by chemotherapy-induced mucositis;

organisms such as Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas and Klebsiella

spp. are likely to cause rapid clinical deterioration and must be

covered with the initial empirical antibiotic therapy.

• Gram-positive infection may require vancomycin therapy.

If fever has not resolved after 3–5 days, empirical antifungal

therapy (e.g. a liposomal amphotericin B preparation,

voriconazole or caspofungin) is added.

• Patients with ALL are susceptible to infection with Pneumocystis

jirovecii , which causes a severe pneumonia. Prophylaxis with

co-trimoxazole is given during chemotherapy. Diagnosis may

require either bronchoalveolar lavage or open lung biopsy.

Treatment is with high-dose co-trimoxazole, initially

intravenously, changing to oral treatment as soon as possible.

• Oral and pharyngeal candida infection is common. Fluconazole is

effective for the treatment of established local infection and for

prophylaxis against systemic candidaemia. Prophylaxis against

other systemic fungal infections, including Aspergillus, using

itraconazole or posaconazole, for example, is usual practice

during high-risk intensive chemotherapy.

• This is often used along with sensitive markers of early

fungal infection to guide treatment initiation (a ‘pre-

emptive approach’). For systemic fungal infection with

Candida or aspergillosis, intravenous liposomal

amphotericin or voriconazole is required.

• Reactivation of herpes simplex infection occurs frequently

around the lips and nose during ablative therapy for acute

leukaemia, and is treated with aciclovir. This may also be

prescribed prophylactically to patients with a history of

cold sores or elevated antibody titres to herpes simplex.

Herpes zoster manifesting as chickenpox or, after

reactivation, as shingles should be treated in the early

stage with high-dose aciclovir, as it can be fatal in

immunocompromised patients.

• The value of isolation facilities, such as laminar flow

rooms, is debatable .The isolation can be psychologically

stressful for the patient.

• Metabolic problems. Frequent monitoring of fluid

balance and renal, hepatic and haemostatic function is

necessary.Patients are often severely anorexic and

diarrhea is common as a consequence of the side-

effects of therapy; they may find drinking difficult and

hence require intravenous fluids and electrolytes.). .

• Renal toxicity occurs with some antibiotics (e.g.

aminoglycosides) and antifungal agents (amphotericin)

• Cellular breakdown during induction therapy (tumour

lysis syndrome) releases intracellular ions and nucleic

acid breakdown products, causing hyperkalaemia,

hyperuricaemia, hyperphosphataemia and

hypocalcaemia.

• This may cause renal failure. Allopurinol and

intravenous hydration are given to try to prevent this.

In patients at high risk of tumour lysis syndrome,

prophylactic rasburicase (a recombinant urate oxidase

enzyme) can be used. Occasionally, dialysis may be

required.

• Psychological problems. Psychological support is a

key aspect of care. Patients should be kept informed,

and their questions answered and fears allayed as far

as possible

• Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

In patients with high-risk acute leukaemia, allogeneic

HSCT can improve 5-year survival from 20% to around

50%.

V1.0

Prognosis

•Without treatment, the median survival of

patients with acute leukaemia is about 5 weeks.

This may be extended to a number of months

with supportive treatment.

Patients who achieve remission with specific

therapy have a better outlook

• Around 80% of adult patients under 60 years of

age with ALL or AML achieve remission,

although remission rates are lower for older

patients.

However, the relapse rate continues to be high.

V1.0

V1.0

V1.0

V1.0