1

Joints of upper limb

1

st

stage

Dr.Kalid Ali Zayer

Acromioclavicular joint

Contents

1 Structures of the Acromioclavicular Joint

o 1.1 Articulating Surfaces

o 1.2 Joint Capsule

o 1.3 Ligaments

2 Neurovascular Supply

3 Movements

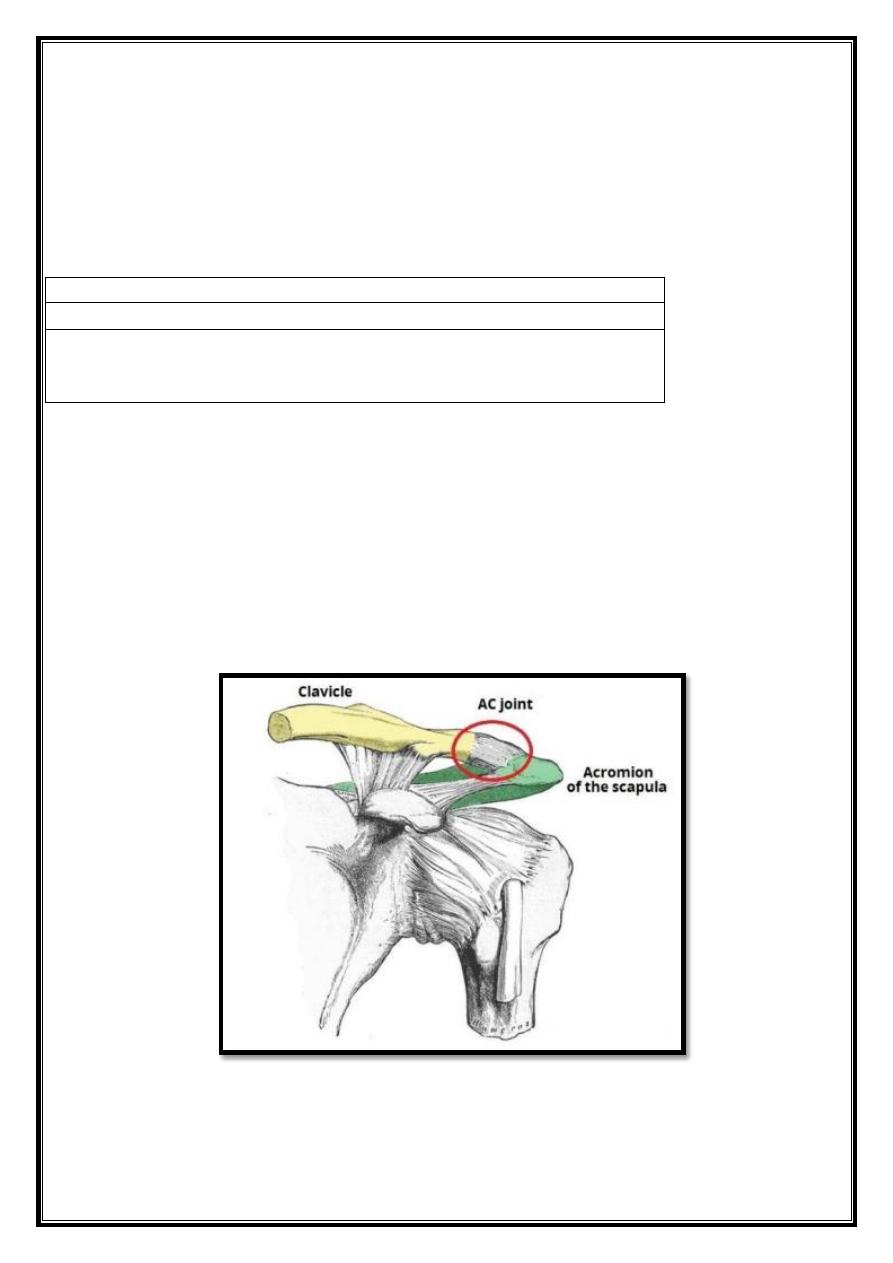

The acromioclavicular joint is a plane type synovial joint. It is located where the lateral end of

the clavicle articulates with the acromion of the scapula. The joint can be palpated during a

shoulder examinaton; 2-3cm medially from the ‘tp’ of the shoulder (formed by the end of the

acromion).

Structures of the Acromioclavicular Joint

Articulating Surfaces

Fig 1– Articulating surfaces of the AC joint.

2

The acromioclavicular joint consists of an articulation between the lateral end of the

clavicle and the acromion of the scapula. It has two atypical features:

The articular surfaces of the joint lined with fibrocartilage (as opposed to hyaline cartilage).

The joint cavity partially divided by an articular disc – a wedge of fibrocartilage suspended

from the upper part of the capsule.

Joint Capsule

The joint capsule consists of a loose fibrous layer, which encloses the two articular surfaces. It

also gives rise to the articular disc. Fibers from the trapezius muscle reinforce the posterior

aspect of the joint capsule.

Joint capsule lined internally by a synovial membrane. This secretes synovial fluid into the

cavity of the joint.

Ligaments

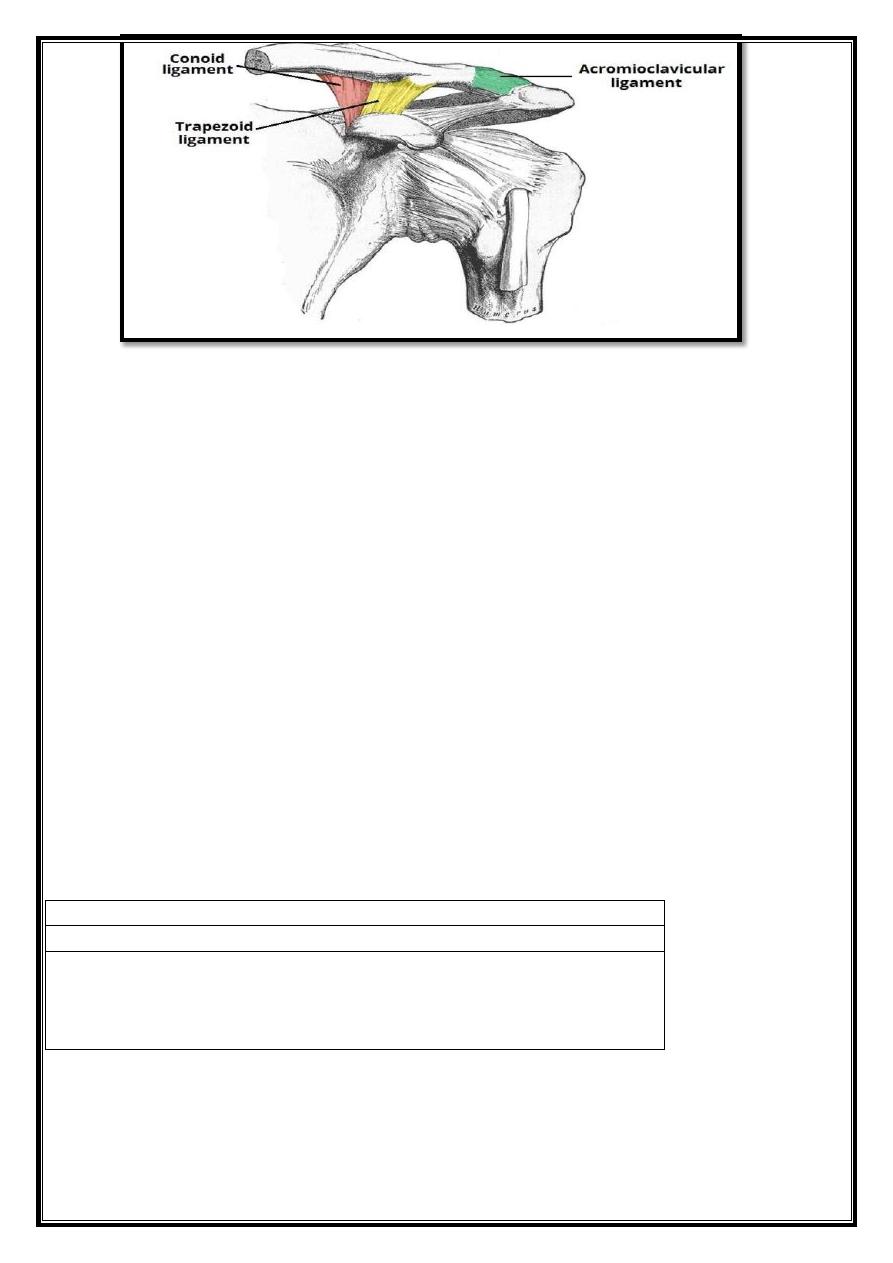

Three main ligaments strengthen the acromioclavicular joint. They can divided into intrinsic

and extrinsic ligaments:

Intrinsic:

o Acromioclavicular ligament – runs horizontally from the acromion to the lateral

clavicle. It covers the joint capsule, reinforcing its superior aspect.

Extrinsic:

o Conoid ligament

– runs vertically from the coracoid process of the scapula to the conoid

tubercle of the clavicle.

o Trapezoid ligament

– runs from the coracoid process of the scapula to the trapezoid line

of the clavicle. Collectively, the conoid and trapezoid ligaments known as the coracoclavicular

ligament. It is a very strong structure, effectively suspending the weight of the upper limb from

the clavicle.

3

Fig 2 – The ligaments of the AC joint.

Neurovascular Supply

Vessels

The arterial supply to the joint is via two vessels:

Suprascapular artery

– arises from the subclavian artery at the thyrocervical trunk.

Thoraco-acromial artery

– arises from the axillary artery.

The veins of the joint follow the major arteries.

Nerves

Articular branches of the suprascapular and lateral pectoral nerves innervate the

acromioclavicular joint. They both arise directly from the brachial plexus.

Movements

The acromioclavicular joint allows a degree of axial rotation and anteroposterior movement.

As no muscles act directly on the joint, all movement is passive, and initiated by movement at

other joints (such as the scapulothoracic joint).

Sternoclavicular joint

Contents

1 Joint Structure

o 1.1 Articulating Surfaces

o 1.2 Joint Capsule

o 1.3 Ligaments

o 1.4 Neurovascular Supply

2 Movements

3 Mobility and Stability

4

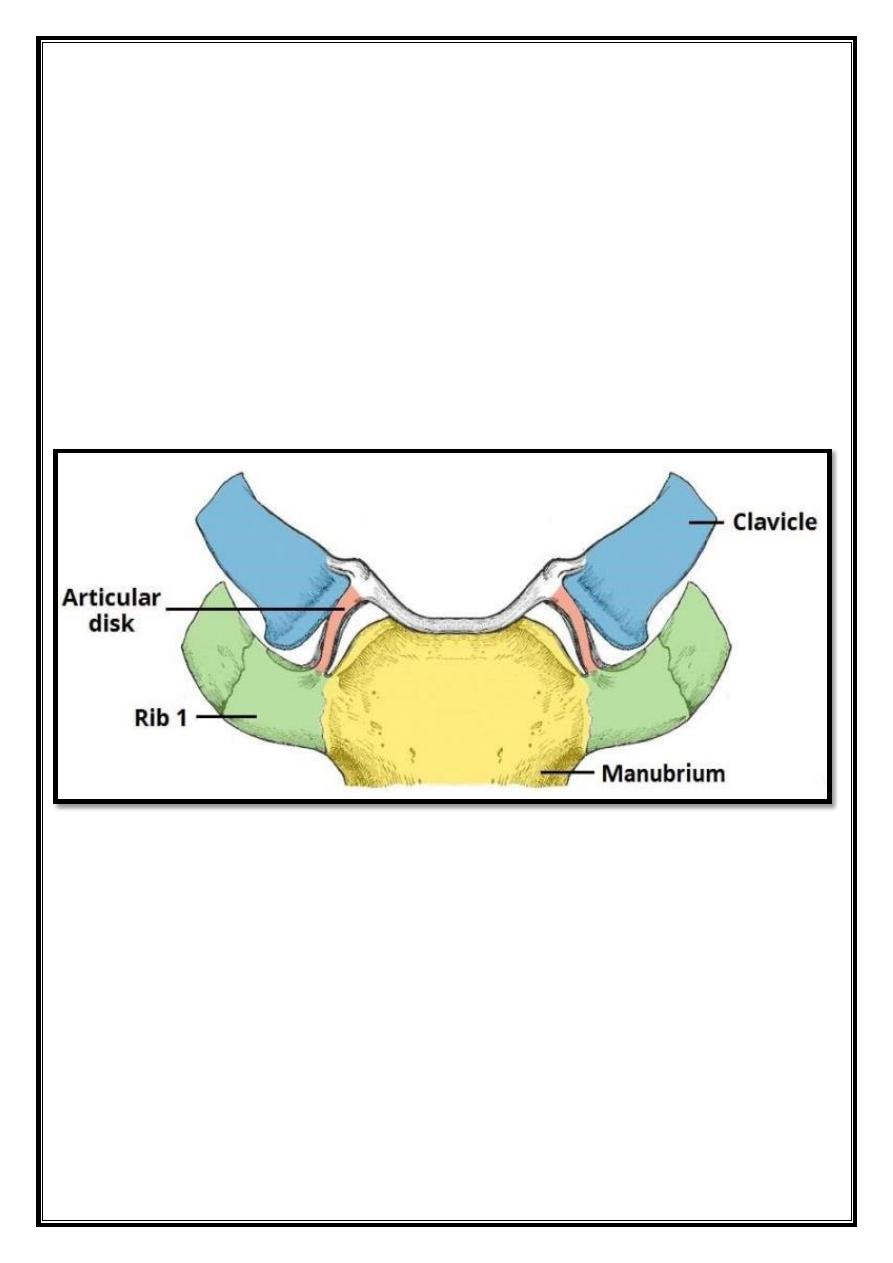

The sternoclavicular joint is a synovial joint between the clavicle and the manubrium of

the sternum.

It is the only attachment of the upper limb to the axial skeleton. Despite its strength, it is a

very mobile joint and can function more like a ball-and-socket type joint.

Joint Structure

Articulating Surfaces

The sternoclavicular joint consists of the sternal end of the clavicle, the manubrium of the

sternum, and part of the 1

st

costal cartilage. The articular surfaces covered

with fibrocartilage (as opposed to hyaline cartilage, present in the majority of synovial joints).

The joint separated into two compartments by a fibrocartilaginous articular disc.

Fig 3 – The articulating surfaces of the sternoclavicular joint

Joint Capsule

The joint capsule consists of a fibrous outer layer, and inner synovial membrane. The fibrous

layer extends from the epiphysis of the sternal end of the clavicle, to the borders of the

articular surfaces and the articular disc. A synovial membrane lines the inner surface and

produces synovial fluid to reduce friction between the articulating structures.

Ligaments

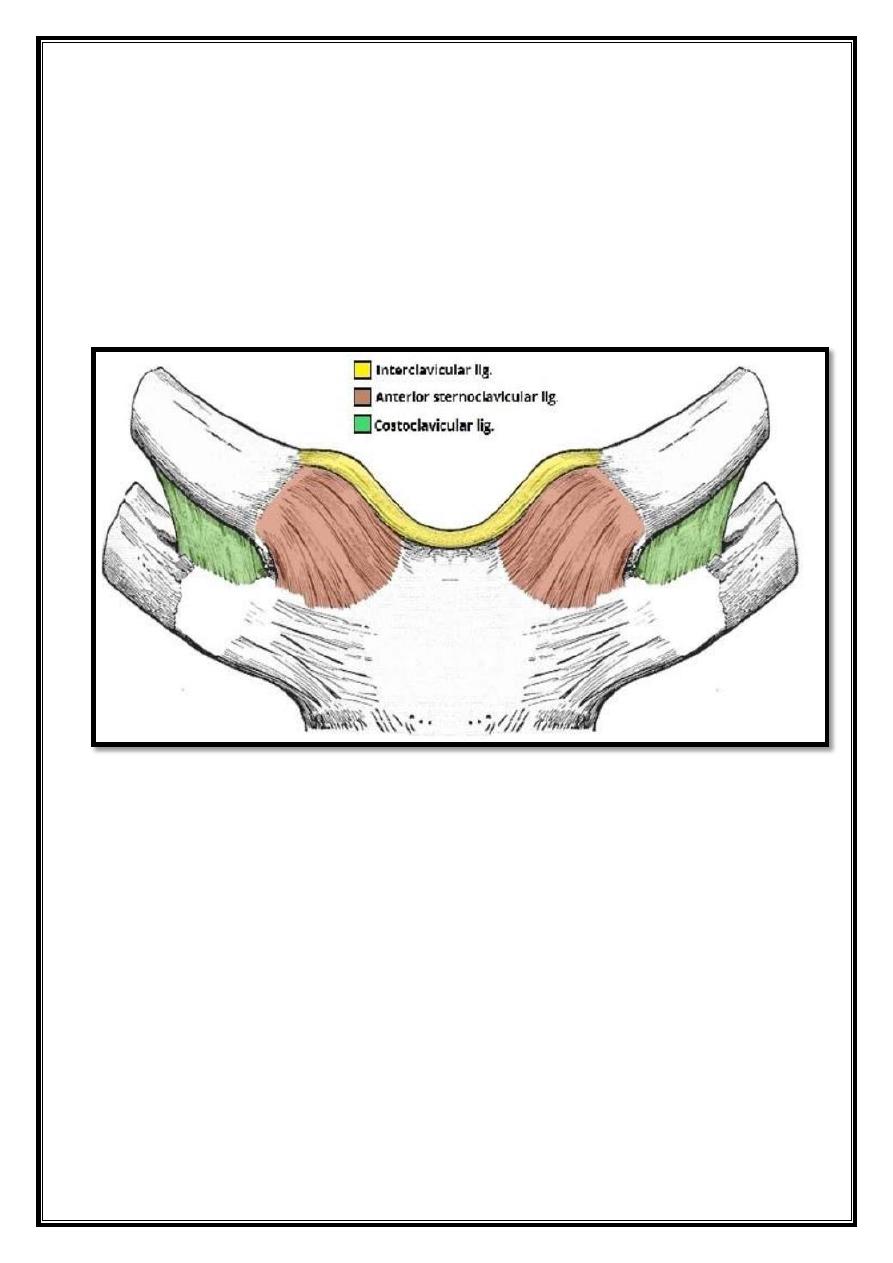

The ligaments of the sternoclavicular joint provide much of its stability. There are four major

ligaments:

5

Sternoclavicular ligaments

(anterior and posterior) – these strengthen the joint

capsule anteriorly and posteriorly.

Interclavicular ligament

– this spans the gap between the sternal ends of each clavicle and

reinforces the joint capsule superiorly.

Costoclavicular ligament

– the two parts of this ligament (often separated by a bursa) bind

at the first rib and cartilage inferiorly and to the anterior and posterior borders of

the clavicle superiorly. It is a very strong ligament and is the main stabilizing force for the

joint, resisting elevation of the pectoral girdle.

The sternoclavicular and interclavicular ligaments considered a thickening of the joint capsule.

Fig 4– The major ligaments of the sternoclavicular joint

Neurovascular Supply

Arterial supply to the sternoclavicular joint is from the internal thoracic artery and

the suprascapular artery.

The medial supraclavicular nerve (C3 and C4) and the nerve to subclavius (C5 and C6) supply

the joint.

Movements

The sternoclavicular joint has a large degree of mobility. Several movements require joint

involvement:

6

Elevation

of the shoulders – shrugging the shoulders or abductng the arm over 90º

Depression

of the shoulders – drooping shoulders or extending the arm at the

shoulder behind the body

Protraction

of the shoulders – moving the shoulder girdle anteriorly

Retraction

of the shoulders – moving the shoulder girdle posteriorly

Rotation

– when the arm raised over the head by flexion the clavicle rotates

passively as the scapula rotates. This is transmitted to the clavicle by the

coracoclavicular ligaments

The costoclavicular ligament acts as a pivot for movements of the clavicle. You can feel this if

you palpate the sternal end of your clavicle and shrug your shoulders; you should feel the

sternal end moving inferiorly.

Mobility and Stability

The sternoclavicular joint is required to accommodate the movements of the upper limb, and

thus has a high degree of mobility. However, it also requires much stability, as it is the only

connection between the upper limb and the axial skeleton. Here we will consider the factors,

which contribute to both its mobility and its stability.

Mobility

Type of joint – being a saddle joint it can move in two axes.

Articular disc – this allows the clavicle and the manubrium to slide over each other more

freely, allowing for the rotation and movement in a third axis.

Stability

Strong joint capsule.

Strong ligaments – particularly the costoclavicular ligament, which transfers stress from the

clavicle to the manubrium (via the costal cartilage).

Shoulder joint

Contents

1 Structures of the Shoulder Joint

o

1.1 Articulating Surfaces

o

1.2 Joint Capsule and Bursae

o

1.3 Ligaments

2 Movements

3 Mobility and Stability

4 Neurovasculature

The shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) is a ball and socket joint between the scapula and

the humerus. It is the major joint connecting the upper limb to the trunk.

It is one of the most mobile joints in the human body, at the cost of joint stability.

7

Structures of the Shoulder Joint

Articulating Surfaces

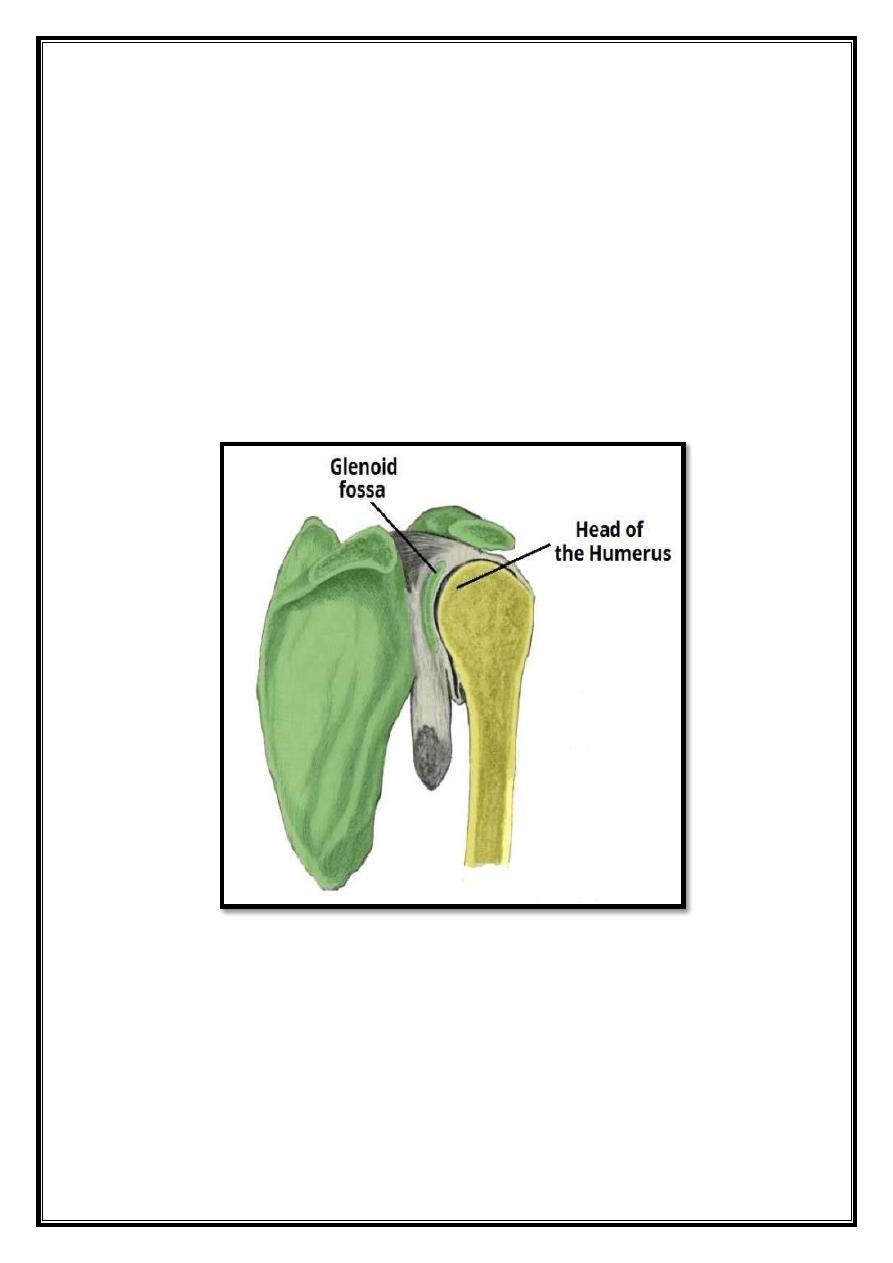

The shoulder joint is formed by the articulation of the head of the humerus with the glenoid

cavity (or fossa) of the scapula. This gives rise to the alternate name for the shoulder joint –

the glenohumeral joint.

Like most synovial joints, the articulating surfaces covered with hyaline cartilage. The head of

the humerus is much larger than the glenoid fossa, giving the joint a wide range of movement

at the cost of inherent instability. To reduce the disproportion in surfaces, a fibrocartilage rim,

called the glenoid labrum, deepens the glenoid fossa.

Joint Capsule and Bursae

The joint capsule is a fibrous sheath, which encloses the structures of the joint.

Fig 5 – The articulating surfaces of the shoulder joint.

It extends from the anatomical neck of the humerus to the border or ‘rim’ of the glenoid

fossa. The joint capsule is lax, permitting greater mobility (particularly abduction).

The synovial membrane lines the inner surface of the joint capsule, and produces synovial

fluid to reduce friction between the articular surfaces.

8

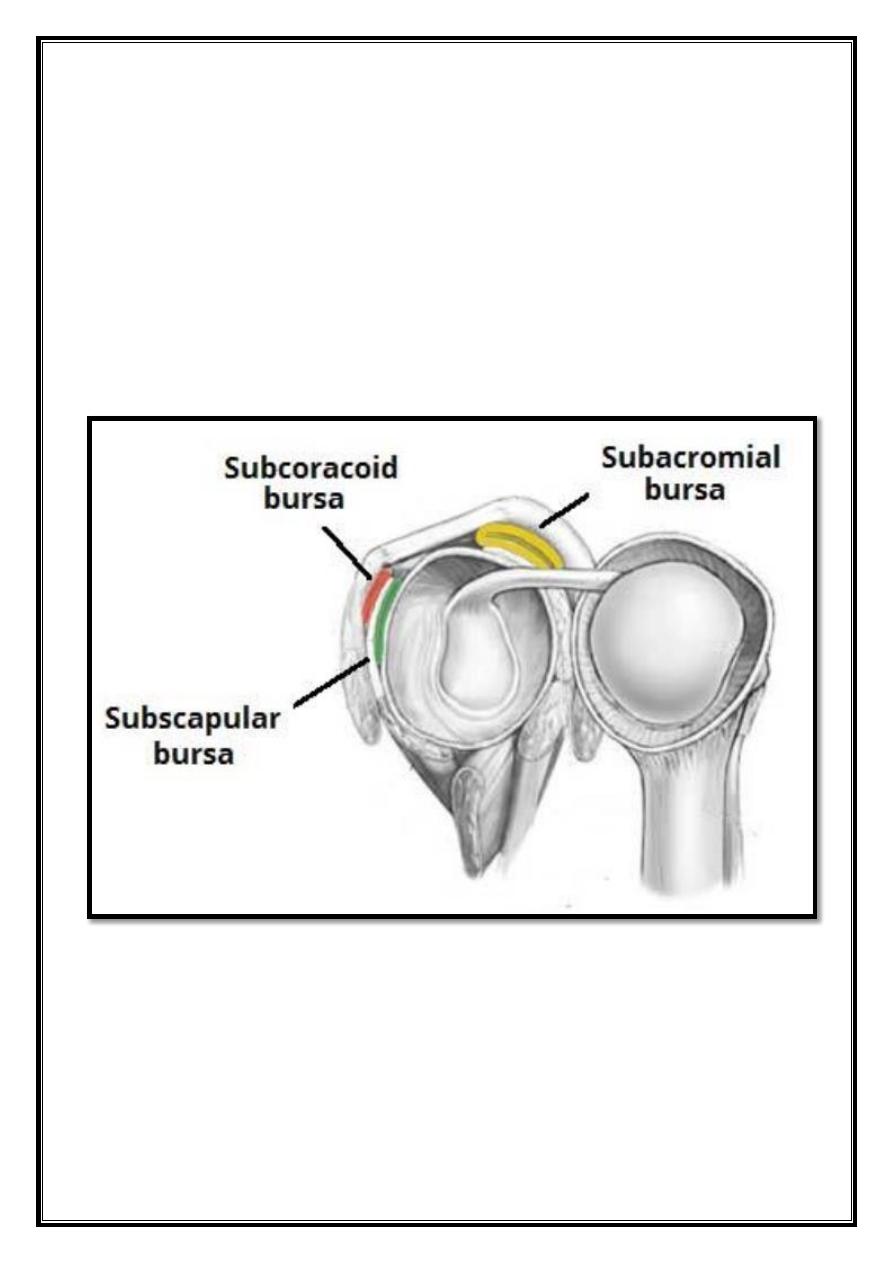

To reduce friction in the shoulder joint, several synovial bursae are present. A bursa is a

synovial fluid filled sac, which acts as a cushion between tendons and other joint structures.

The bursae that are important clinically are:

Subacromial

– Located deep to the deltoid and acromion, and superficial to the

supraspinatus tendon and joint capsule. The subacromial bursa reduces friction beneath the

deltoid, promoting free motion of the rotator cuff tendons. Subacromial bursitis (i.e.

inflammation of the bursa) can be a cause of shoulder pain.

Subscapular

– Located between the subscapularis tendon and the scapula. It reduces wear

and tear on the tendon during movement at the shoulder joint.

There are other minor bursae present between the tendons of the muscles around the joint,

but this is beyond the scope of this article.

Fig 6 – The major bursae of the shoulder joint.

9

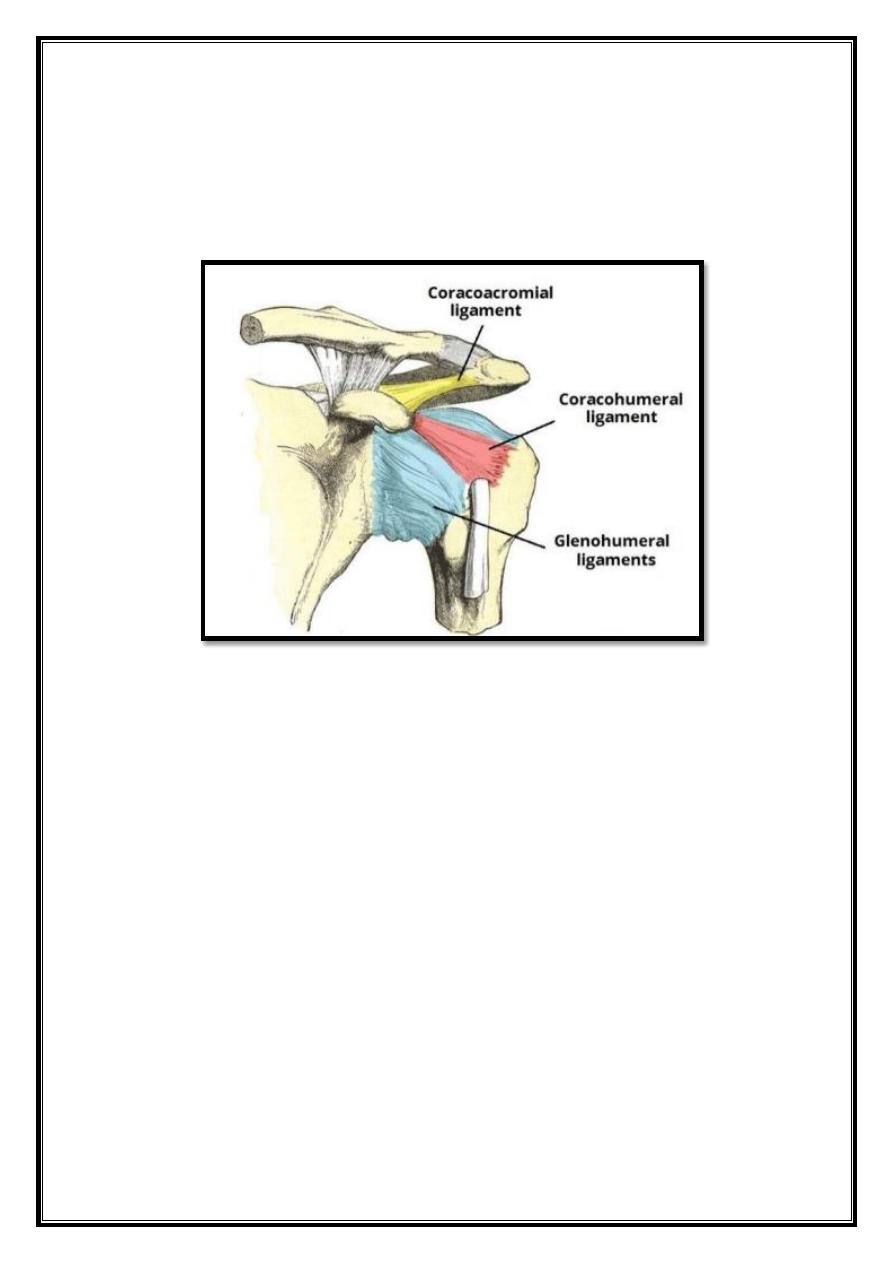

Ligaments

In the shoulder joint, the ligaments play a key role in stabilizing the bony structures.

Glenohumeral ligaments

(superior, middle and inferior) – The joint capsule is formed by

this group of ligaments connecting the humerus to the glenoid fossa. They are the main

source of stability for the shoulder, holding it in place and preventing it from dislocating

anteriorly. They act to stabilize the anterior aspect of the joint.

Fig 7 – The ligaments of the shoulder joint. The transverse humeral ligament is not

shown on this diagram

Coracohumeral ligament

– Attaches the base of the coracoid process to the greater tubercle

of the humerus. It supports the superior part of the joint capsule.

Transverse humeral ligament

– Spans the distance between the two tubercles of the

humerus. It holds the tendon of the long head of the biceps in the intertubercular groove.]

Coraco–clavicular ligament

– This is composed of the trapezoid and conoid ligaments and

runs from the clavicle to the coracoid process of the scapula. They work alongside the

acromioclavicular ligament to maintain the alignment of the clavicle in relation to the

scapula. They have significant strength but large forces (e.g. after a high-energy fall) can

rupture these ligaments as part of an acromio-clavicular joint (ACJ) injury. In severe ACJ

injury, the coraco-clavicular ligaments may require surgical repair.

The other major ligament is the coracoacromial ligament. Running between the acromion and

coracoid process of the scapula it forms the coraco-acromial arch. This structure overlies the

shoulder joint, preventing superior displacement of the humeral head.

10

Movements

As a ball and socket synovial joint, there is a wide range of movement permitted:

Extension (upper limb backwards in sagittal plane)

o Produced by the posterior deltoid, latissimus dorsi and teres

major.

Flexion (upper limb forwards in sagittal plane)

o Produced by the pectoralis major, anterior deltoid and coracobrachialis. Biceps brachii

weakly assists in forward flexion.

Abduction (upper limb away from midline in coronal plane)

o The frst 0-15 degrees of abducton is produced by the supraspinatus. The middle fbres

of the deltoid are responsible for the next 15-90 degrees. Past 90 degrees, the scapula

needs to be rotated to achieve abduction – that is carried out by the trapezius and

serratus anterior.

Adduction (upper limb towards midline in coronal plane)

o Produced by contraction of pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi and teres major.

Internal Rotation (rotation towards the midline, so that the thumb is pointing

medially)

o Produced by contraction of subscapularis, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres

major

and anterior deltoid.

External Rotation (rotation away from the midline, so that the thumb is pointing

laterally)

o Produced by contraction of the infraspinatus and teres minor.

Mobility and Stability

The shoulder joint is one of the most mobile in the body, at the expense of stability. Here, we

shall consider the factors the permit movement, and those that contribute towards joint

structure.

Factors that contribute to mobility:

Type of joint

– A ball and socket joint.

Bony surfaces

– Shallow glenoid cavity and large humeral head – there is a 1:4

disproportion in surfaces. A commonly used analogy is the golf ball and tee.

Inherent laxity of the joint capsule.

Factors that contribute to stability:

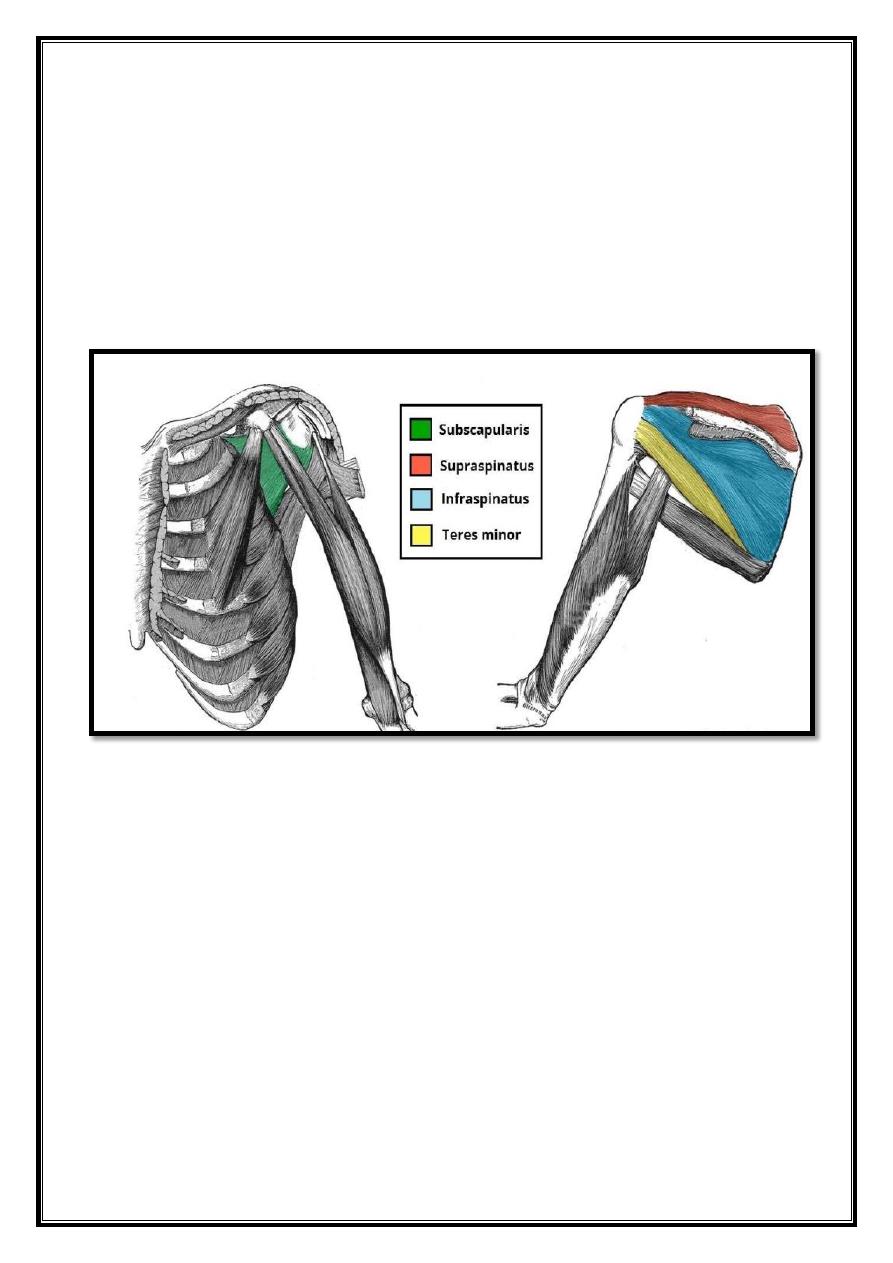

Rotator cuff muscles

– As dynamic stabilizers, these muscles surround the shoulder

11

joint, attaching to the tuberosities of the humerus, whilst also fusing with the joint capsule.

The resting tone of these muscles act to compress the humeral head into the glenoid cavity.

Glenoid labrum:

This is a fibrocartilaginous ridge surrounding the glenoid cavity. It deepens

the cavity and creates a seal with the head of humerus, reducing the risk of dislocation.

Ligaments

– The ligaments act to reinforce the joint capsule, and forms the coraco-acromial

arch. The most important factor is the inferior glenohumeral ligament, which acts like a

sling.

Biceps tendon

– Another dynamic stabilizer, it acts as a minor humeral head depressor,

thereby contributing to stability.

Fig 8 – The rotator cuff muscles, which act to stabilize the shoulder joint.

Neurovasculature

The shoulder joint supplied by the anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries, which

are both branches of the axillary artery. Branches of the suprascapular artery, a branch of the

thyrocervical trunk, also contribute. The axillary, suprascapular and lateral pectoral nerves

provide innervation.