IDA

Anemias

• Definition : Anemia is a blood disorder

characterized by abnormally low levels of healthy

red blood cells (RBCs) or reduced hemoglobin

(Hgb), the iron-bearing protein in red blood cells

that delivers oxygen to tissues throughout the body.

Reduced blood cell volume (hematocrit) is also

considered anemia.

• The reduction of any or all of the three blood

parameters reduces the oxygen-carrying capability

of the blood, causing reduced oxygenation of body

tissues, a condition called hypoxia.

• The reduction of any or all of the three blood parameters

reduces the oxygen-carrying capability of the blood,

causing reduced oxygenation of body tissues, a condition

called hypoxia.

• Description: All tissues in the human body need a regular

supply of oxygen to stay healthy and perform their

functions. RBCs contain Hgb, a protein pigment that

allows the cells to carry oxygen (oxygenate) tissues

throughout the body. RBCs live about 120 days and are

normally replaced in an orderly way by the bone marrow,

spleen, and liver.

• As RBCs break down, they release Hgb into the blood

stream, which is normally filtered out by the kidneys and

excreted. The iron released from the RBCs is returned to

the bone marrow to help create new cells.

• Anemia develops when either blood loss, a slow-down in the

production of new RBCs (erythropoiesis), or an increase in red

cell destruction (hemolysis) causes significant reductions in

RBCs, Hgb, iron levels, and the essential delivery of oxygen to

body tissues.

• Anemia can be mild, moderate, or severe enough to lead to

life-threatening complications. More than 400 different types

of anemia have been identified. Many of them are rare. Most

are caused by ongoing or sudden blood loss.

• Other causes include vitamin and mineral deficiencies,

inherited conditions, and certain diseases that affect red cell

production or destruction.

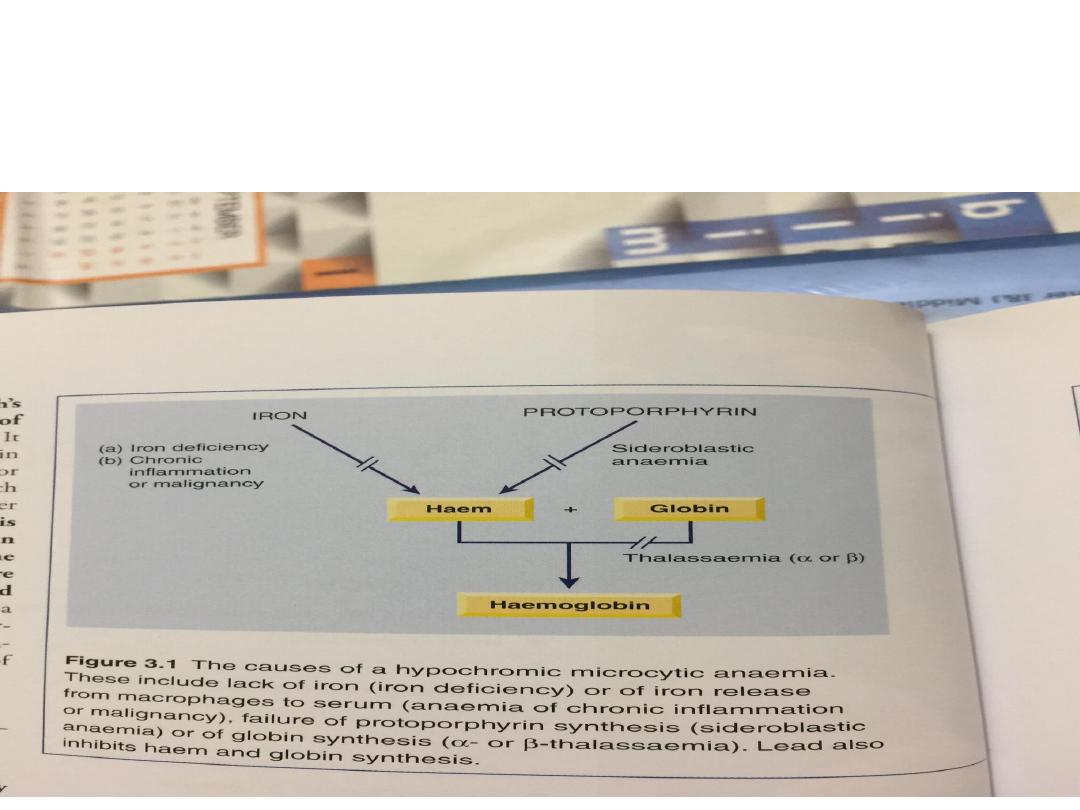

• It can also be classified based on the size of red blood

cells and amount of hemoglobin in each cell. If the cells are

small, it is microcytic anemia.

If they are large, it is macrocytic anemia

while if they are normal sized, it is normocytic anemia.

• Diagnosis in men is based on a hemoglobin of less than

130 to 140 g/L (13 to 14 g/dL), while in women, it must be

less than 120 to 130 g/L (12 to 13 g/dL). Further testing is

then required to determine the cause.

• Anemia is the most common blood disorder, affecting

about a third of the global population.

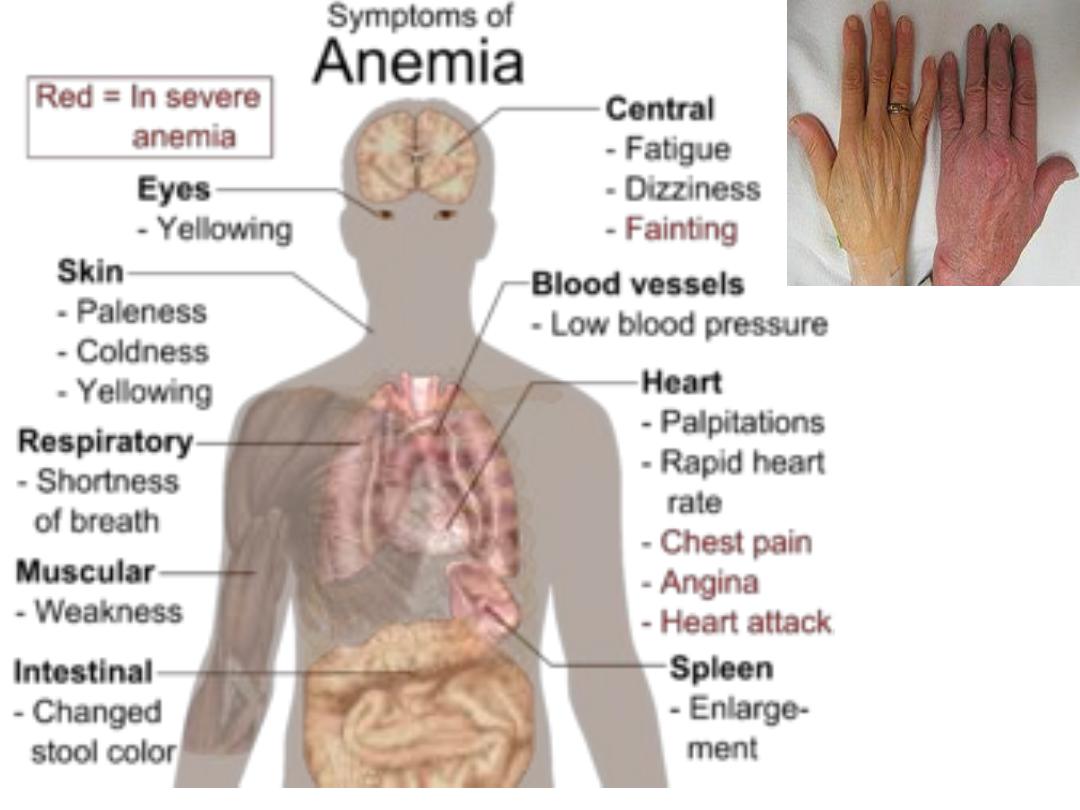

• Anemia goes undetected in many people and symptoms

can be minor. The symptoms can be related to an

underlying cause or the anemia itself. Most commonly,

people with anemia report feelings of weakness or tired,

and sometimes poor concentration.

•

• They may also report shortness of breath on exertion. In

very severe anemia, the body may compensate for the

lack of oxygen-carrying capability of the blood by

increasing cardiac output. The patient may have

symptoms related to this, such as palpitations, angina (if

pre-existing heart disease is present),

intermittent claudication of the legs, and symptoms

of heart failure

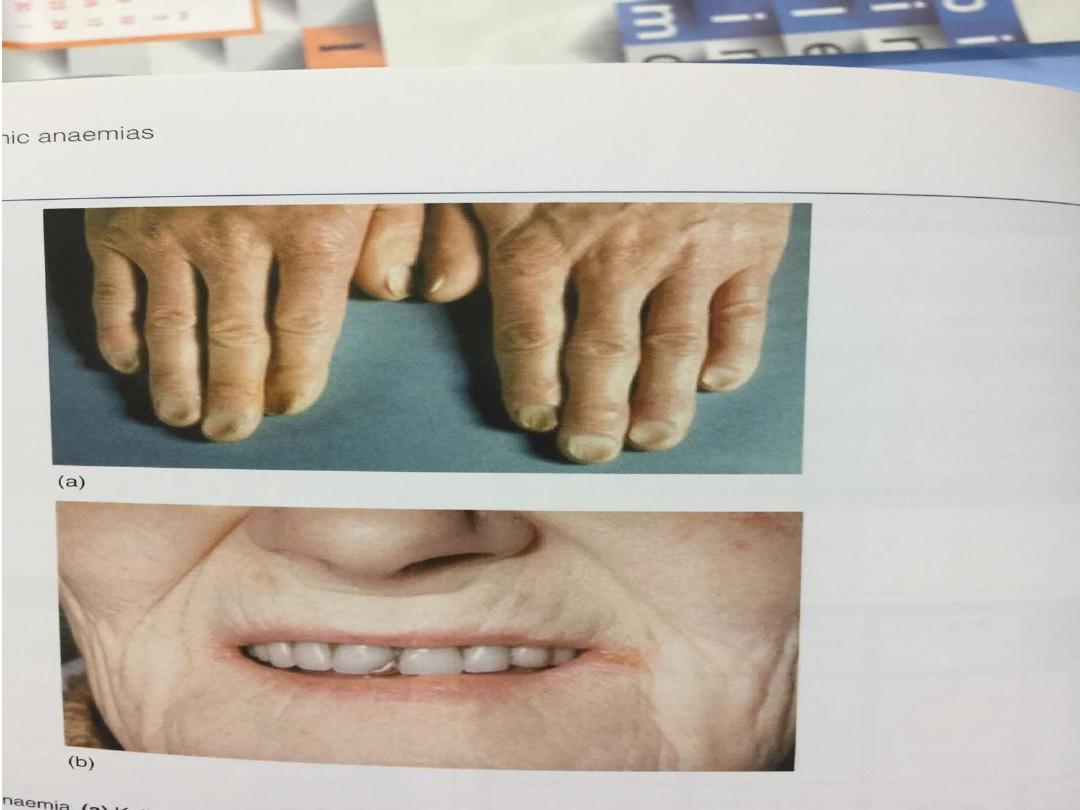

• On examination, the signs exhibited may

include pallor (pale skin,

lining mucosa, conjunctiva and nail beds), but this is not a

reliable sign. There may be signs of specific causes of

anemia, e.g., koilonychia (in iron

deficiency), jaundice (when anemia results from

abnormal break down of red blood cells — in hemolytic

anemia),

• bone deformities (foundin thalassemia major)

or leg ulcers (seen in sickle-cell disease). In severe

anemia, there may be signs of a hyperdynamic

circulation: tachycardia (a fast heart rate), bounding

pulse, flow murmurs, and cardiac ventricular

hypertrophy (enlargement). There may be signs

of heart failure. Pica, the consumption of non-food

items such as ice,

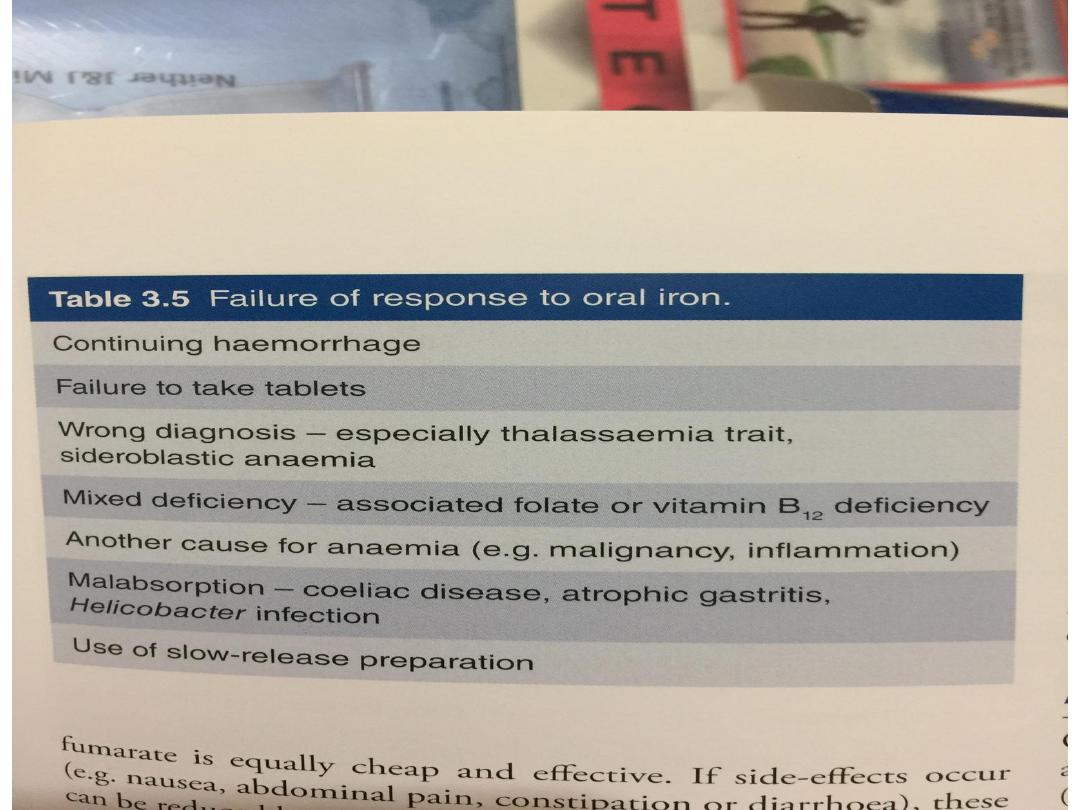

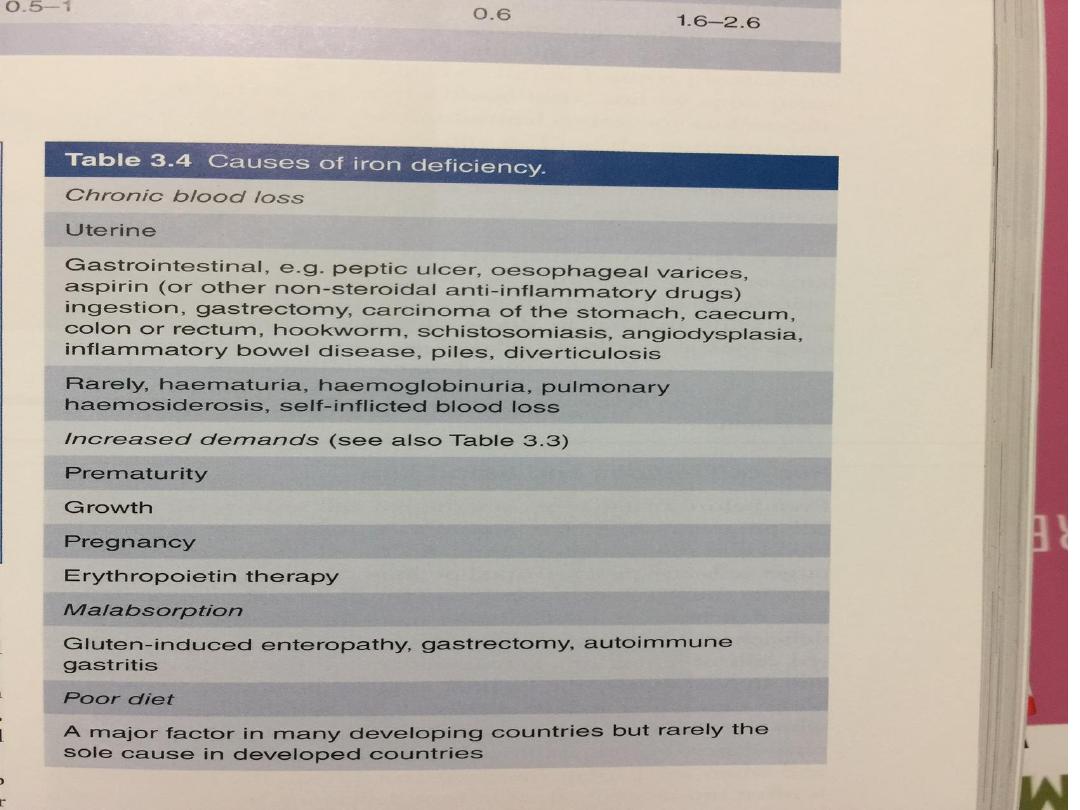

Iron deficiency anaemia

• This occurs when iron losses or physiological

requirements exceed absorption

Blood loss

• The most common explanation in men and

postmenopausal women is gastrointestinal blood loss. This

may result from occult gastric or colorectal malignancy,

gastritis, peptic ulceration, inflammatory bowel disease,

diverticulitis, polyps and angiodysplastic lesions.

• Worldwide, hookworm and schistosomiasis are the most

common causes of gut blood loss In women of child-

bearing age, menstrual blood loss, pregnancy and

breastfeeding contribute to iron deficiency by depleting

iron stores; in developed countries, one-third of

premenopausal women have low iron stores but only 3%

display iron-deficient haematopoiesis. Very rarely, chronic

haemoptysis or haematuria may cause iron deficiency.

Malabsorption

• A dietary assessment should be made in all patients to

ascertain their iron intake. Gastric acid is required to

release iron from food and helps to keep iron in the soluble

ferrous state Achlorhydria in the elderly or that due to

drugs such as proton pump inhibitors may contribute to the

lack of iron availability from the diet, as may previous

gastric surgery.

• Iron is absorbed actively in the upper small intestine and

hence can be affected by coeliac disease

• Physiological demands At times of rapid growth, such as

infancy and puberty, iron requirements increase and may

outstrip absorption. In pregnancy, iron is diverted to the

fetus, the placenta and the increased maternal red cell

mass, and is lost with bleeding at parturition

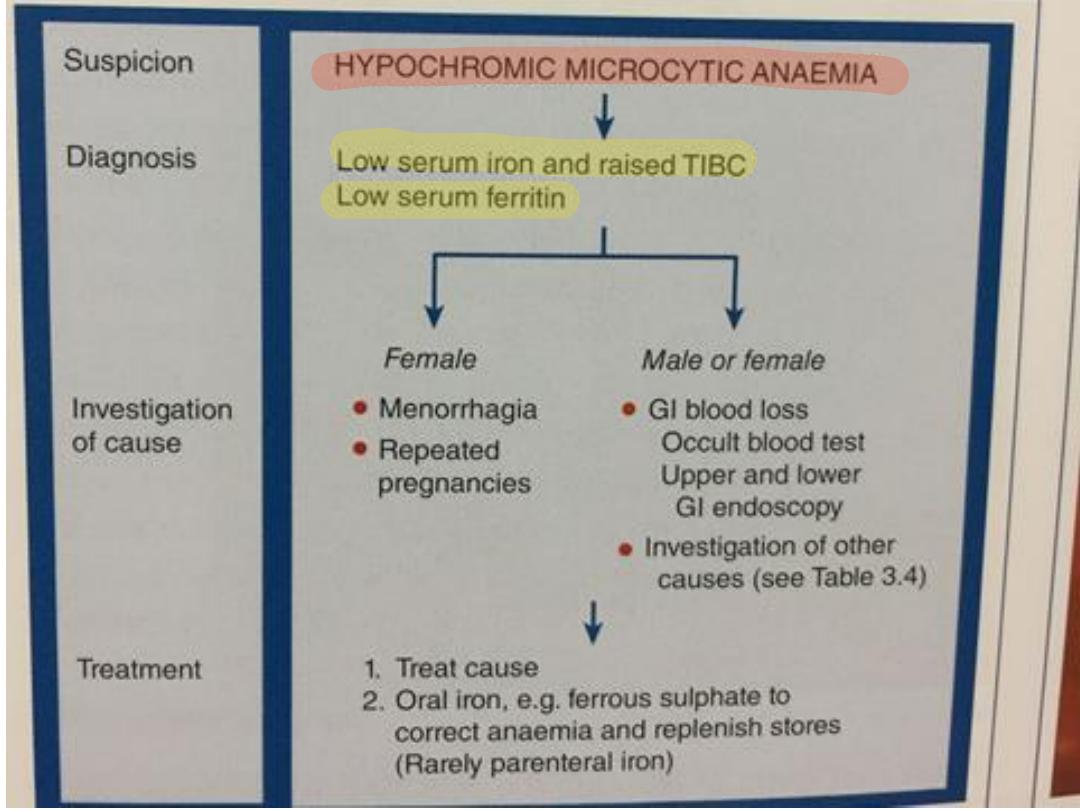

Investigations Confirmation of iron deficiency :

• Plasma ferritin is a measure of iron stores in tissues and is the

best single test to confirm iron deficiency

• Plasma iron and total iron binding capacity (TIBC) are measures

of iron availability; hence they are affected by many factors

besides iron stores.

Investigation of the cause

• This will depend upon the age and sex of the patient, as well as

the history and clinical findings. In men and in post-menopausal

women with a normal diet, the upper and lower gastrointestinal

tract should be investigated by endoscopy or radiological

studies.

• Serum antiendomysial or anti-transglutaminase antibodies and

possibly a duodenal biopsy are indicated to detect coeliac

disease. In the tropics, stool and urine should be examined for

parasites

Management

• Unless the patient has angina, heart failure or

evidence of cerebral hypoxia, transfusion is not

necessary and oral iron replacement is appropriate.

• Ferrous sulphate 200 mg 3 times daily is adequate

and should be continued for 3–6 months to replete

iron stores.

• The haemoglobin should rise by around 10 g/L

every 7–10 days and a reticulocyte response will be

evident within a week. A failure to respond

adequately may be due to non-compliance,

continued blood loss, malabsorption or an incorrect

diagnosis.

• Patients with malabsorption or chronic gut disease may

need parenteral iron therapy. Previously, iron dextran

or iron sucrose was used but new preparations of iron

isomaltose and iron carboxymaltose have fewer allergic

effects and are preferred.