1

GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

ASS. PROF.DR. MAHA SHAKIR HASSAN

Lec 4

Small and Large Intestines

DEVELOPMENTAL ANOMALIES

• Atresia or stenosis, the former being complete failure of development of

the intestinal lumen and the latter representing only narrowing.

Duplication usually takes the form of well-formed saccular to tubular

cystic structures, which may or may not communicate with the lumen of

the small intestine.

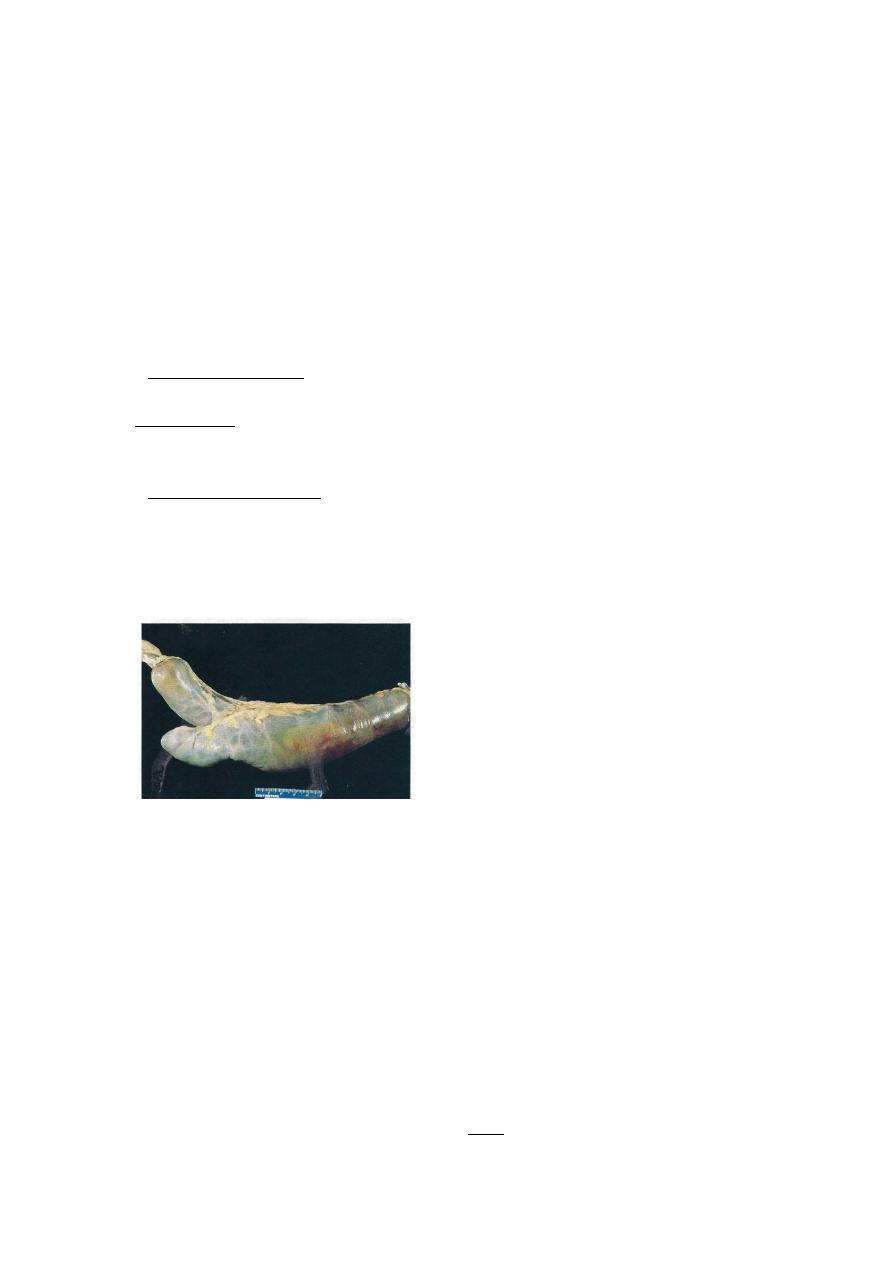

• Meckel diverticuluin is the most common and innocuous of the

anomalies. It results from failure of involution of the omphalomesenteric

duct, leaving a persistent blind-ended tubular protrusion up to 5 to 6 cm

long. The diameter is variable. Usually in the ilium, and composed of all

layers of small intestine. They are generally asymptomatic

Meckel diverticulum. The blind pouch is located on the antimesenteric side of the small bowel.

Hirschsprung Disease: Congenital Megacolon

Distention of the colon to greater than 6 or 7 cm in diameter (megacolon)

occurs as a congenital and as an acquired disorder. Hirschsprung disease

(congenital megacolon) results during development, the caudal migration

of neural crest-derived cells along the alimentary tract arrests at some

point before reaching the anus. Hence, an aganglionic segment is left that

lacks both the Meissner submucosal and Auerbach myenteric plexuses.

This causes functional obstruction and progressive distention of the colon

proximal to the affected segment. In most instances, only the rectum and

sigmoid are aganglionic, but in about a fifth of cases a longer segment,

2

and rarely the entire colon, is affected. Approximately 50% of cases

result from mutations in RET gene and RET ligands, as this signaling

pathway is required for development of the myenteric nerve plexus

MORPHOLOGY

The critical lesion is the lack of ganglion cells, and of ganglia, in the

muscle wall and submucosa of the affected segment. The affected

segment is not distended. proximal properly innervated segment that

undergoes dilation. Thus, when only the distal colon is affected, the

remainder of the colon becomes massively distended. The wall may be

thinned by distention or in some cases is thickened by compensatory

muscle hypertrophy.

Clinical Features.

In most cases a delay occurs in the initial

passage of meconium, which is followed by vomiting in 48 to 72 hours.

The principal threat to life is superimposed enterocolitis with fluid and

electrolyte disturbances. More rarely, the distended colon perforates,

usually in the thin-walled cecum. The diagnosis is established by

documenting the absence of ganglion cells in the nondistended bowel

segment.

Acquired megacolon may result from (1) Chagas disease, in which the

trypanosomes directly invade the bowel wall to destroy the plexuses, (2)

organic obstruction of the bowel by a neoplasm or inflammatory stricture,

(3) toxic megacolon complicating ulcerative colitis (discussed later), or

(4) a functional psychosomatic disorder.

VASCULAR DISORDERS

Angiodysplasia:

Tortuous dilatation of submucosal and mucosal blood vessels, most often

in the cecum or right colon. Usually only after the 6th decade.

The

pathogenesis of angiodysplasia remains undefined but has been attributed

to mechanical and congenital factors.

Degenerative vascular changes

related to aging may also have some role.

Hemorrhoids:

It is variceal dilitation of the anal and perianal submucosal venous plexus.

Pathogenesis: Persistently elevated venous pressure within hemorrhoidal

plexus.

3

Predisposing conditions:

1. Chronic constipation.

2. Pregnancy.

3. Rarely portal hypertention.

Malabsorption Syndromes and diarrhea

Malabsorption, which presents most commonly as chronic diarrhea, is

characterized by defective absorption of fats, fat- and water-soluble

vitamins, proteins, carbohydrates, electrolytes and minerals, and water.

Chronic malabsorption can be accompanied by weight loss, anorexia,

abdominal distention. A hallmark of malabsorption is steatorrhea,

characterized by excessive fecal fat and bulky, frothy, greasy, yellow or

clay-colored stools.

Most common types:

1-

Gluten-sensitive enteropathy

, also known as celiac disease,

is the prototype of a noninfectious cause of malabsorption resulting from

a reduction in small intestinal absorptive surface area. The basic disorder

in celiac disease is sensitivity to gluten, the component of wheat and

related grains (oat, barley, and rye) that contains the water-insoluble

protein gliadin. There is autoimmune mechanism responsible of

development of such disease. The small intestinal mucosa, when exposed

to gluten, accumulates large numbers of B cells and plasma cells

sensitized to gliadin; accumulation of lymphocytes in gastric and colonic

mucosa also may occur. In addition to filling the lamina propria,

lymphocytes also cross into the epithelial space, with accompanying

damage to surface enterocytes. Total flattening of mucosal villi (and

hence loss of surface area) is the outcome, affecting the proximal more

than the distal small intestine.

The age of presentation with symptomatic diarrhea and malnutrition

varies from infancy to mid adulthood; removal of gluten from the diet is

met with dramatic improvement. There is, however, a low long-term risk

of malignant disease on the order of a two-fold increase over the usual

rate. Intestinal lymphomas, especially T-cell lymphomas, are

disproportionately

represented;

other

malignancies

include

gastrointestinal and breast carcinomas.

2-Tropical sprue

4

Tropical sprue resembles celiac disease in symptomatology but occurs

almost exclusively in persons living in or visiting the tropics. No specific

causal agent has been identified, but the appearance of malabsorption

within days or a few weeks of an acute diarrheal enteric infection strongly

implicates an infectious process, also there is prompt response to broad-

spectrum antibiotic therapy. Small intestinal changes vary from near

normal to a severe diffuse enteritis with villous flattening in contrast to

celiac disease, injury is seen at all levels of the small intestine.

IDIOPATHIC INFLAMMATOR BOWEL DISEASES

Crohn Disease

This disease may affect any level of the alimentary tract, from mouth to

anus. Active cases of CD are often accompanied by extraintestinal

manifistations of immune origin, such as iritis and uveitis, sacroiliitis,

migratory polyarthritis, erythema nodosum, hepatic pericholangitis and

sclerosing cholangitis (bile duct inflammatory disorders), and obstructive

uropathy. Systemic amyloidosis is a rare late consequence. Thus, CD

must be viewed as a systemic inflammatory disease with predominant

gastrointestinal involvement.

Epidemiology.

Worldwide in distribution, CD is much more

prevalent in the United States, Great Britain and is rare in Asia and

Africa. It occurs at any age, from young childhood to advanced age, but

the peak incidence is between the second and third decades of life.

Females are affected slightly more often than males. Whites appear to

develop the disease two to five times more often than do nonwhites.

MORPHOLOGY

In CD, there is gross involvement of the small intestine alone in about

30% of Cases, of small intestine and colon in 40%, and of the colon alone

in about 30%. When fully developed, CD is characterized by (1)

sharply delimited and typically transmural involvement of the bowel

by an inflammatory process with mucosal damage, (2) the presence

of noncaseating granulomas in about 35% of cases, and (3) fissuring

with formation of fistulae.

In diseased segments hypertrophy of the muscularis propria. As a result

the lumen is almost always narrowed; in the small intestine this is

evidenced radiagraphically as the “string sign,” a thin stream of barium

passing through the diseased segment. Strictures may occur in the colon

but are usually less severe.

5

A classic feature of CD is the sharp demarcation of diseased bowel

segments from adjacent uninvolved bowel. When multiple bowel

segments are involved, the intervening bowel is essentially normal

(“skip” lesions).

In the intestinal mucosa, early disease exhibits focal mucosal ulcers

resembling canker sores (aphthous ulcers).

With progressive disease, ulcers coalesce into long, serpentine linear

ulcers, which tend to be oriented along the axis of the bowel, because the

intervening mucosa tends to be relatively spared, it acquires a coarsely

textured, cobblestone appearance.

Narrow fissures develop between the folds of the mucosa, often

penetrating deeply through the bowel wall all the way to serosa.

Further extension of fissures leads to fistula or sinus tract formation,

either to an adherent viscus, to the outside skin, or into a blind cavity to

form a localized abscess.

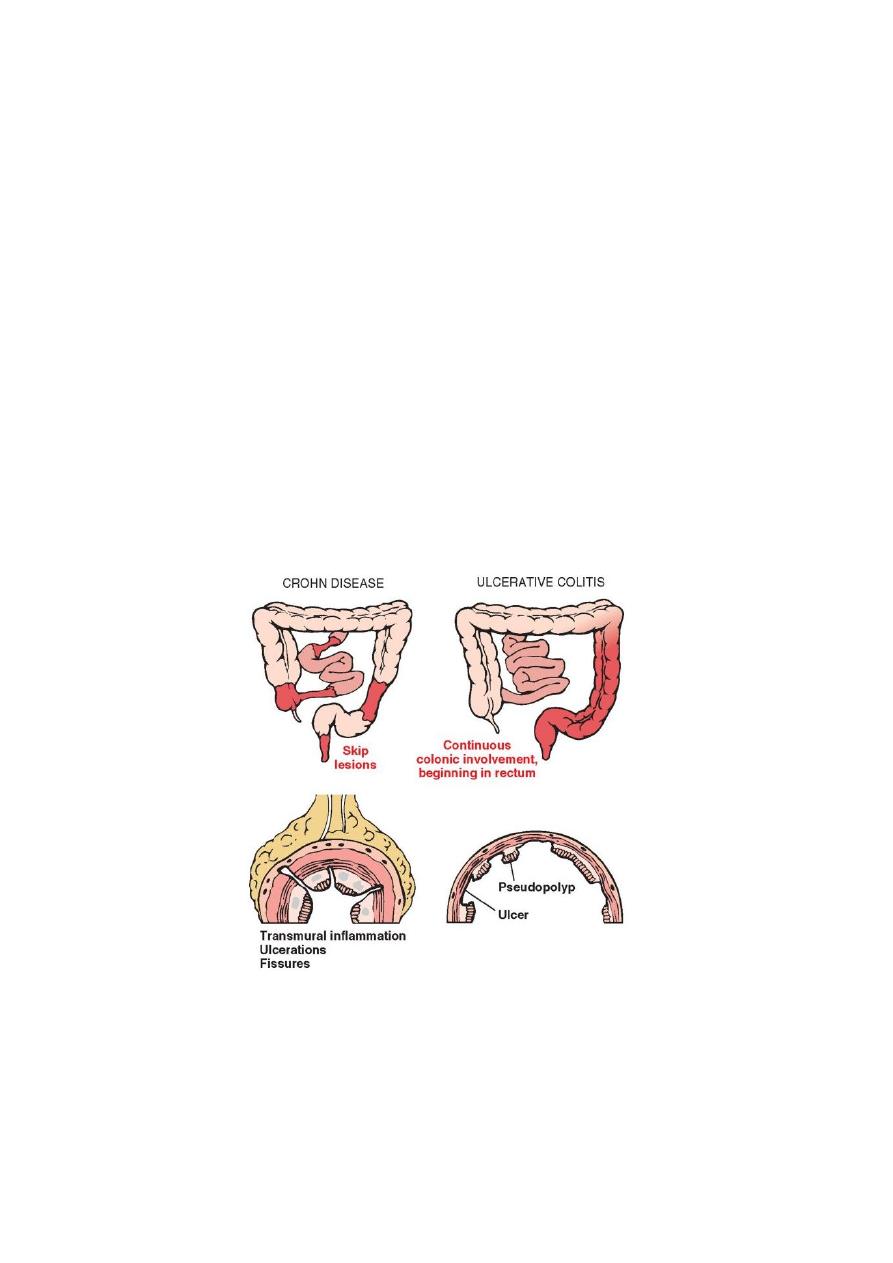

Distribution of lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. The distinction between Crohn disease and

ulcerative colitis is primarily based on morphology

.

By microscopic examination, the mucosa exhibits several

characteristic features :

6

(1) inflammation, with neutrophilic infiltration into the epithelial

layer and accumulation within crypts to form crypt abscesses;

(2) ulceration, which is the usual outcome of active disease: and

(3) chronic mucosal damage in the form of architectural

distortion, atrophy, and metaplasia.

(4) Granulomas may be present anywhere in the alimentary

tract, even in patients with CD limited to one bowel segment.

However, the absence of granulomas does not preclude a

diagnosis of CD.

(5) In diseased segments. the muscularis mucosae and

muscularis propria are usually markedly thickened, and fibrosis

affects all tissue layers.

(6) Lymphoid aggregates scattered through the various tissue

layers and in the extramural fat also are characteristic.

(7) Particularly important in patients with long-standing chronic

disease are dysplastic changes appearing in the mucosal

epithelial cells. It is related to a five-told to six-fold increased

risk of carcinoma, particularly of the colon.

7

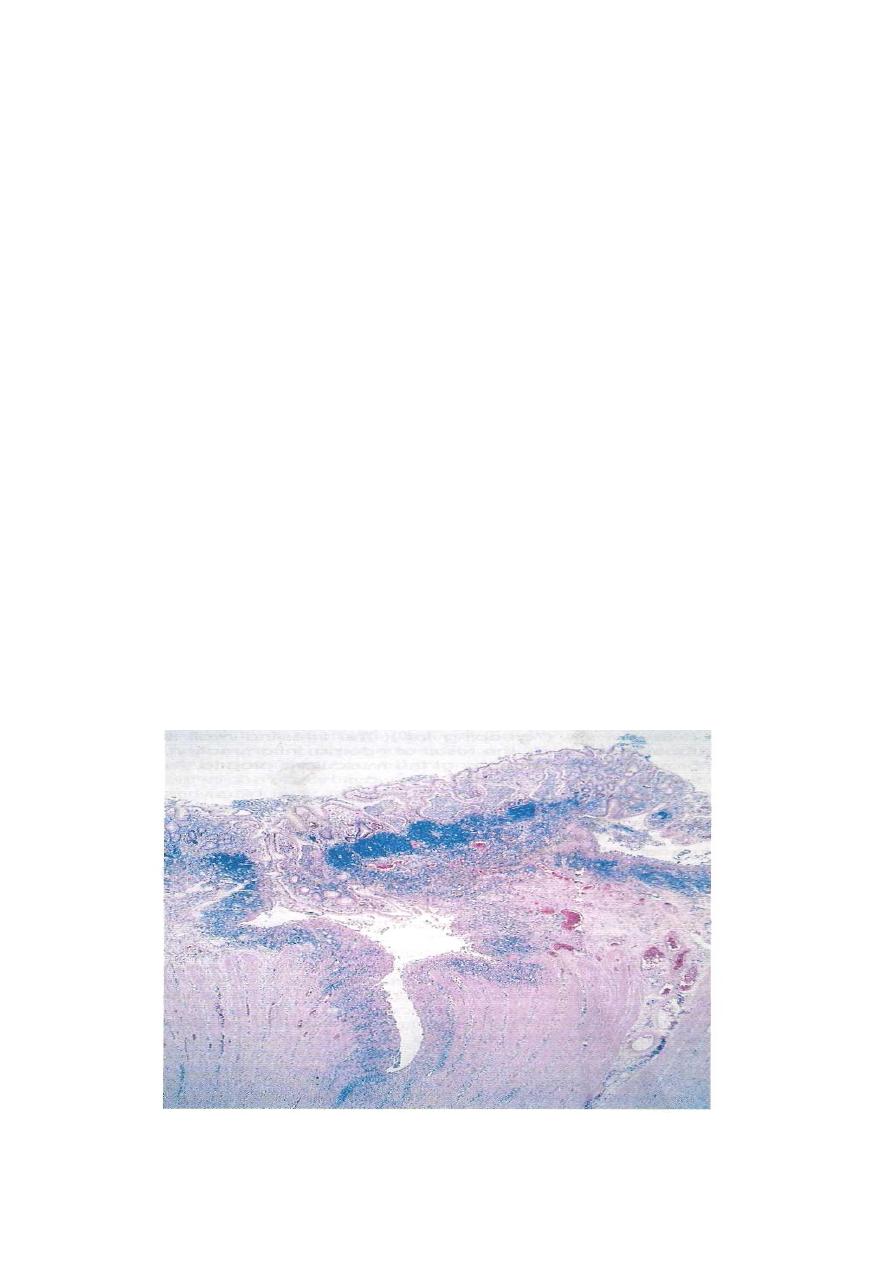

Crohn disease of the colon showing a deep fissure extending into the muscle wall, a second,

shallow ulcer (and relative preservation of the intervening mucosa). Abundant lymphocyte

aggregates are present, evident as dense blue patches of cells at the interface between mucosa and

submucosa

Clinical Features. The presentation of CD is highly variable

and ultimately unpredictable. The dominant manifestations are

recurrent episodes of diarrhea, crampy abdominal pain, and

fever lasting days to weeks.

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an ulceroinflammatory disease affecting the

colon but limited to the mucosa and submucosa except in the most severe

cases. UC begins in the rectum and extends proximally in a continuous

fashion, sometimes involving the entire colon. Like CD, UC is a systemic

disorder associated in some patients with migratory polyarthritis,

sacroiliitis, ankylosing spondylitis, uveitis, erythema nodosum, and

hepatic involvement (pericholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis).

There are several important differences between UC and CD:

• In UC, well-formed granulomas are absent.

• UC does not exhibit skip lesions.

• The mucosal ulcers in UC rarely extend below the submucosa, and there

is surprisingly little fibrosis.

• Mural thickening does not occur in UC, and the serosal surface is

usually completely normal.

• Patients with UC are at greater risk for carcinoma.

Epidemiology

.

UC is somewhat more common than CD in the United States and Western

countries, but it is infrequent in Asia, Africa, and South America.

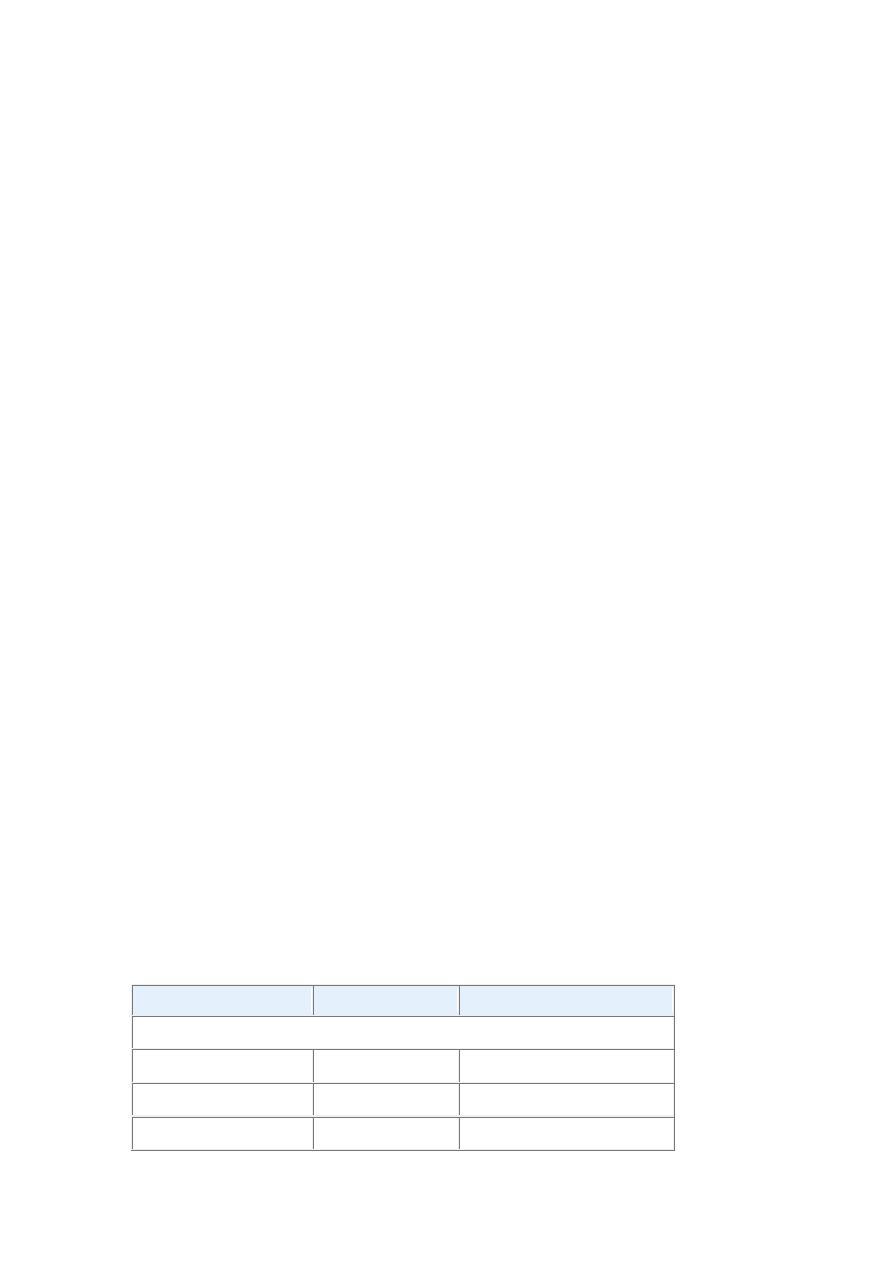

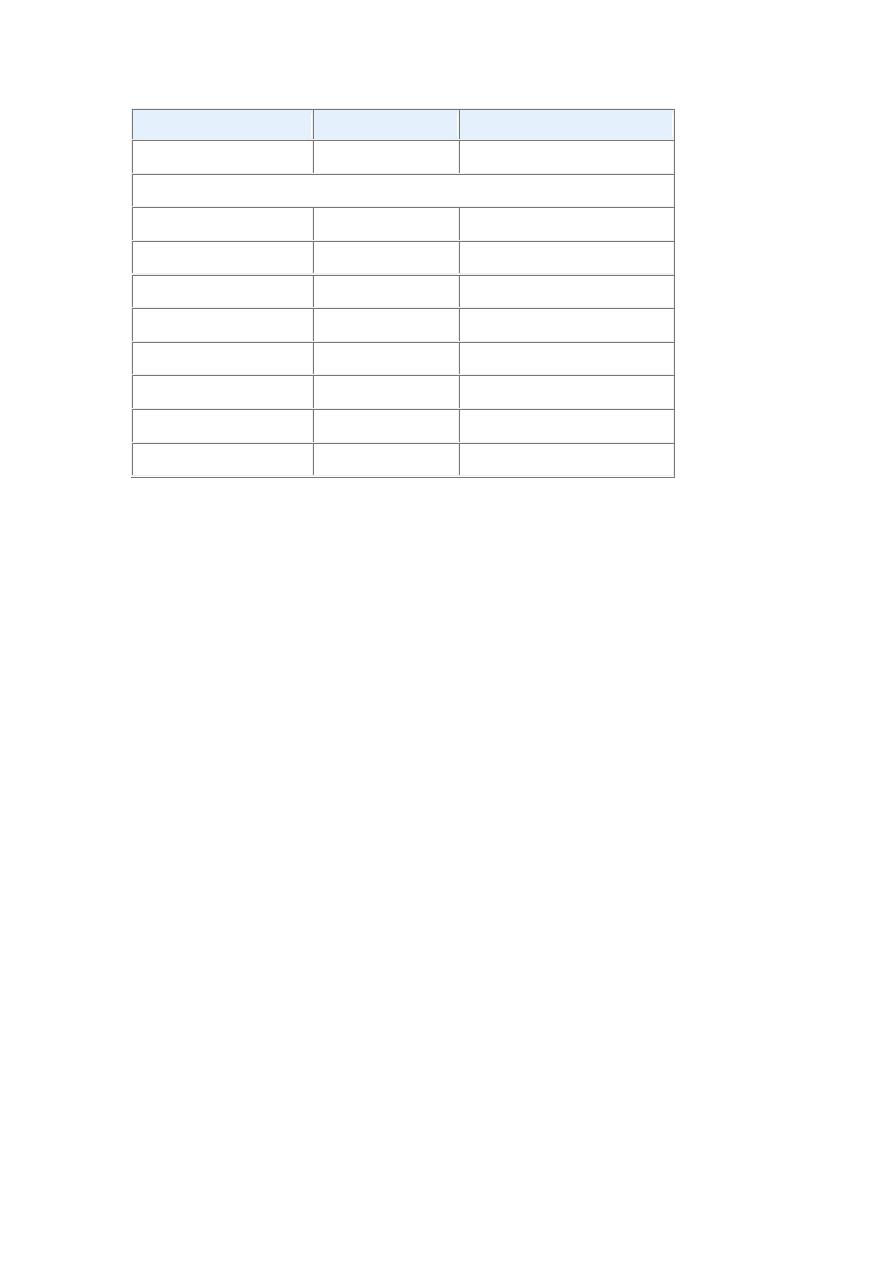

Features That Differ between Crohn Disease and Ulcerative Colitis

Feature

Crohn Disease Ulcerative Colitis

MACROSCOPIC

Bowel region

Ileum ± colon

Colon only

Distribution

Skip lesions

Diffuse

Stricture

Yes

Rare

8

Feature

Crohn Disease Ulcerative Colitis

Wall appearance

Thick

Thin

MICROSCOPIC

Inflammation

Transmural

Limited to mucosa

Pseudopolyps

Moderate

Marked

Ulcers

Deep, knife-like Superficial, broad-based

Lymphoid reaction Marked

Moderate

Fibrosis

Marked

Mild to none

Serositis

Marked

Mild to none

Granulomas

Yes (

∼35%)

No

Fistulae/sinuses

Yes

No

Morphology.

Grossly:

ulcerative colitis always involves the rectum and extends

proximally in a continuous fashion to involve part or all of the

colon.

Skip lesions are not seen .

Disease of the entire colon is termed pancolitis ,while left-sided

disease extends no farther than the transverse colon. Limited distal

disease may be referred to descriptively as ulcerative proctitis or

ulcerative proctosigmoiditis.

The small intestine is normal, although mild mucosal

inflammation of the distal ileum, backwash ileitis, may be present

in severe cases of pancolitis.

Grossly, involved colonic mucosa may be slightly red and granular

or have extensive, broad-based ulcers

Isolated islands of regenerating mucosa often bulge into the lumen

to create pseudopolyps

. Unlike Crohn disease, mural thickening is not present, the

serosal surface is normal, and strictures do not occur.

However, inflammation and inflammatory mediators can damage

the muscularis propria and disturb neuromuscular function leading

9

to colonic dilation and toxic megacolon, which carries a

significant risk of perforation.

Histologic features:

inflammatory infiltrates, crypt abscesses .

the inflammatory process is diffuse and generally limited to the

mucosa and superficial submucosa .

In severe cases, extensive mucosal destruction may be

accompanied by ulcers that extend more deeply into the

submucosa, but the muscularis propria is rarely involved.

Submucosal fibrosis, mucosal atrophy, and distorted mucosal

architecture remain as residua of healed disease but histology may

also revert to near normal after prolonged remission.

Granulomas are not present in ulcerative colitis.

The most serious complication of UC is the development of

colon carcinoma. Two factors govern the risk: duration of the

disease and its anatomic extent. It is believed that with 10 years

of disease limited to the left colon the risk is minimal, and at 20

years the risk is on the order of 2%, With pancolitis, the risk of

carcinoma is 10% at 20 years and 15% to 25% by 30 years.

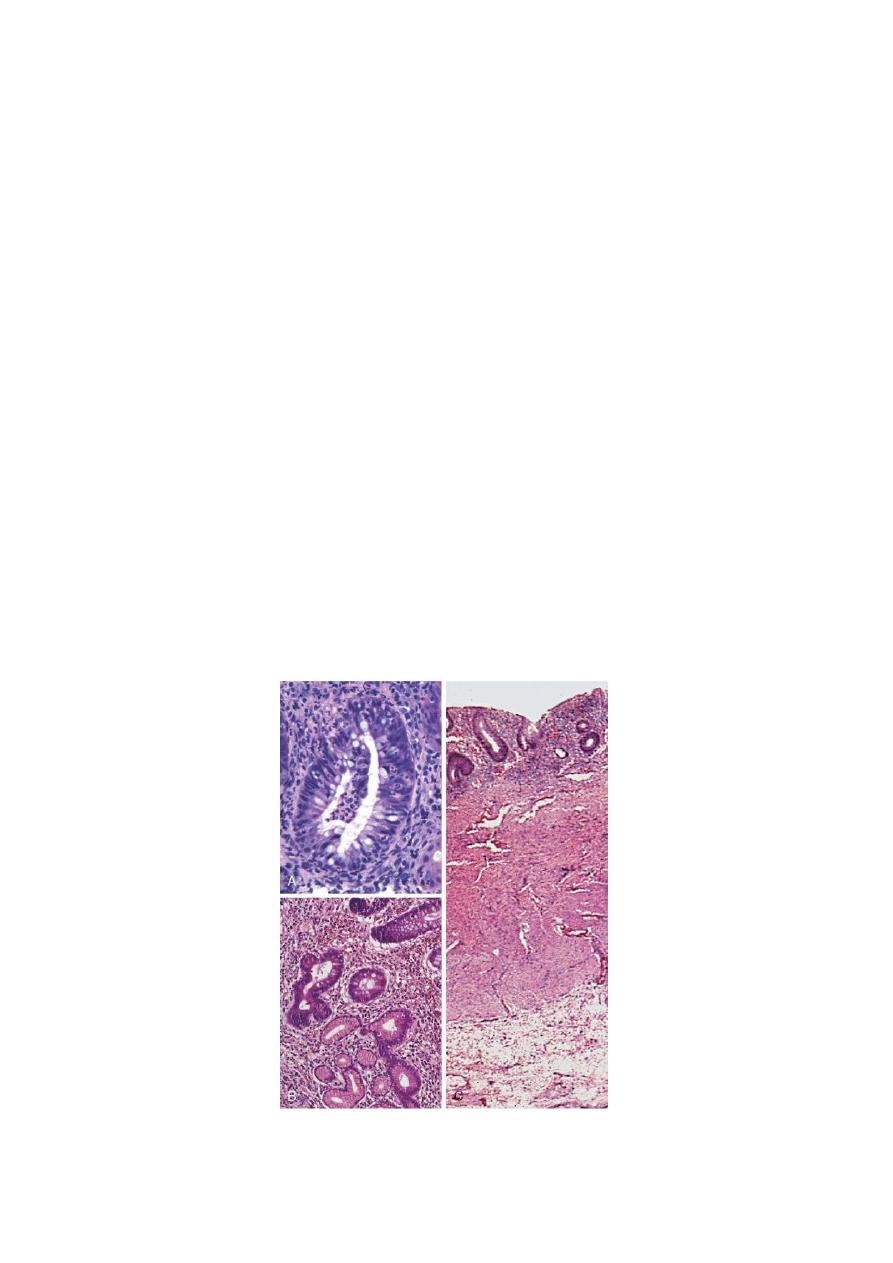

A, Crypt abscess. B, Pseudopyloric metaplasia (bottom).

C, Disease is limited to the mucosa

10

.

Clinical Features.

UC is a chronic relapsing and remitting disorder marked by

attacks of bloody mucoid diarrhea that may persist for days,

weeks, or months and then subside, only to recur after an

asymptomatic interval of months to years or even decades.

Extraintestinal

manifestations,

particularly

migratory

polyarthritis, are more common with UC than with CD.

Uncommon but life-threatening complications include:

severe diarrhea and electrolyte derangements, massive

hemorrhage, severe colonic dilation (toxic megacolon) with

potential rupture, and perforation with peritonitis. Inflammatory

strictures of the colorectum.

Diagnosis can usually be made by endoscopic examination and

biopsy. The most feared long-term complication of UC is

cancer.