Cellular Events:

)Leukocyte Recruitment and Activation)

an important function of the inflammatory response is to deliver leukocytes to the

site of injury and to activate them. Leukocytes ingest offending agents, kill bacteria

and other microbes, and eliminate necrotic tissue and foreign substances. A price

that is paid for the defensive potency of leukocytes is that, once activated, they

may induce tissue damage and prolong inflammation, since the leukocyte products

that destroy microbes can also injure normal host tissues. Therefore, key to the

normal function of leukocytes in host defense is to ensure that they are recruited

and activated only when needed (i.e., in response to foreign invaders and dead

tissue)

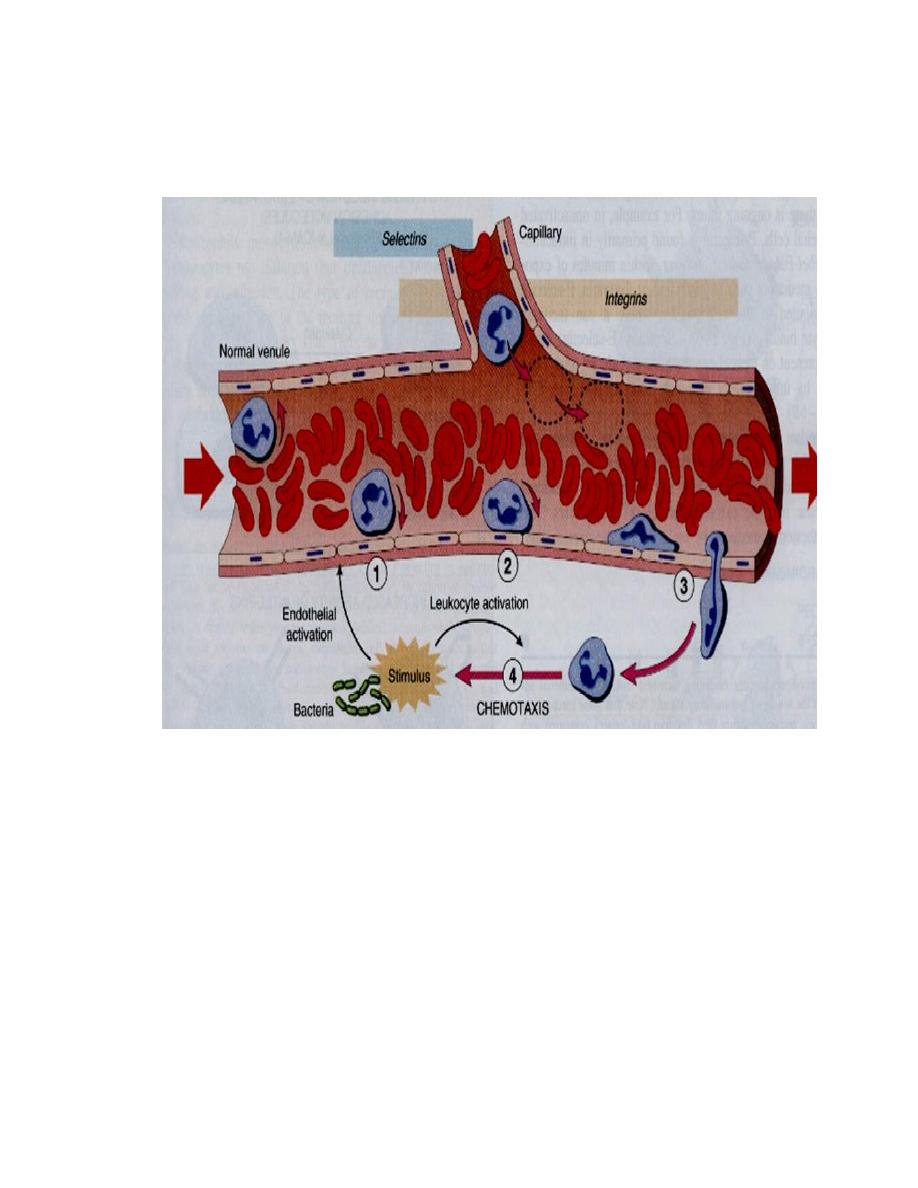

Leukocyte Recruitment

The sequence of events in the recruitment of leukocytes from the vascular

lumen to the extravascular space consists of

(1) margination, adhesion to endothelium, and rolling along the vessel wall.

(2) firm adhesion to the endothelium;

(3) transmigration between endothelial cells; and

(4) migration in interstitial tissues toward a chemotactic stimulus .

Rolling, adhesion, and transmigration are mediated by the binding of

complementary adhesion molecules on leukocytes and endothelial surfaces.

Chemical mediators-chemoattractants and certain cytokines-affect these

processes by modulating the surface expression or avidity of the adhesion

molecules and by stimulating directional movement of the leukocytes .

Emigration of neutrophils

Sequence of events in leukocytes emigration in inflammation:

1. Margination 2. rolling 3. adhesion 4. transmigration and movement

toward injurious agent (stimulus)

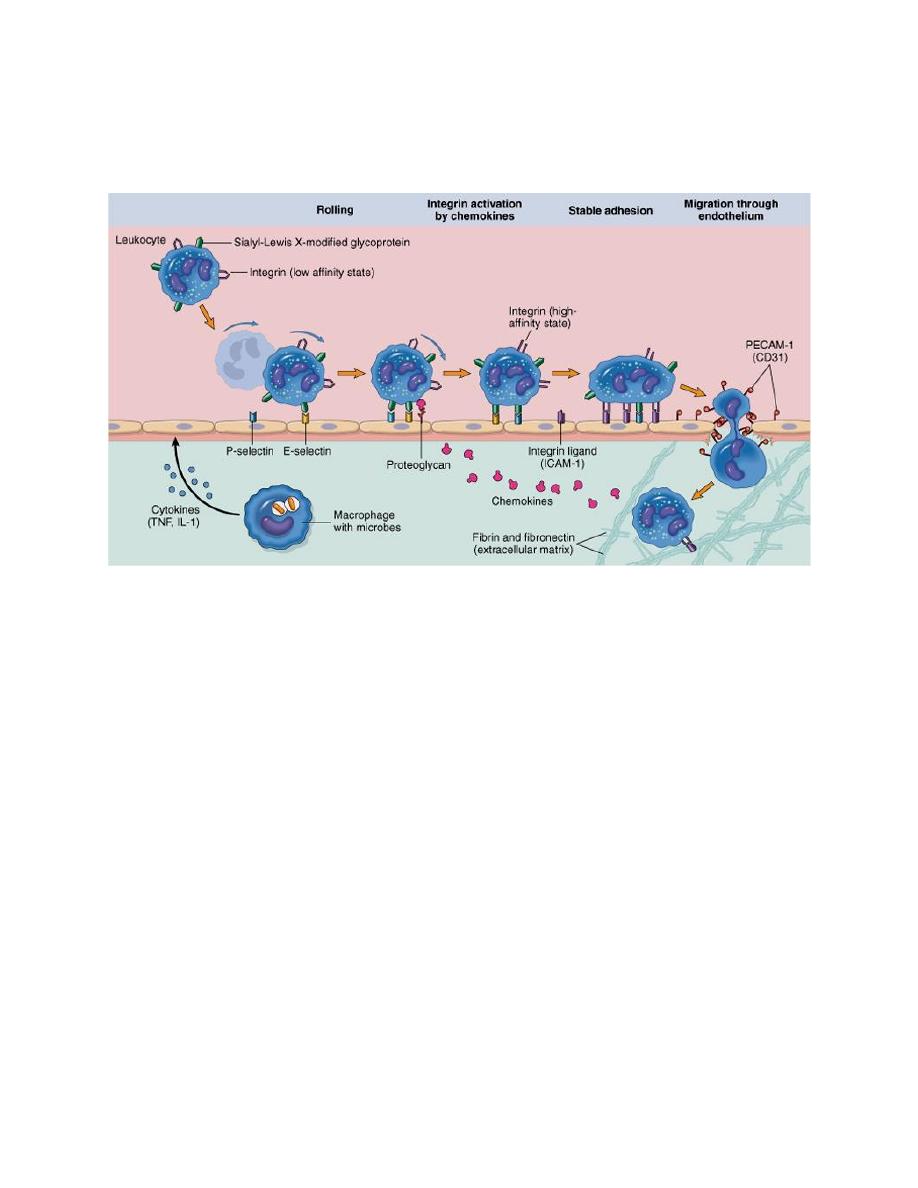

Leukocyte (neutrophil) migration through blood vessels

The leukocytes first roll, then become activated and adhere to endothelium, then

transmigrate across the endothelium, pierce the basement membrane, and migrate

toward chemoattractants emanating from the source of injury. Different molecules

play predominant roles in different steps of this process - selectins in rolling;

chemokines (usually displayed bound to proteoglycans) in activating the

neutrophils to increase avidity of integrins; integrins in firm adhesion; and CD31

(PECAM-1) in transmigration. ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IL-1,

interleukin 1; PECAM-1, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1; TNF,

tumor necrosis factor.

Chemotaxis

After extravasating from the blood, leukocytes migrate toward sites of infection

or injury along a chemical gradient by a process called chemotaxis

.

Both exogenous and endogenous substances can be chemotactic for leukocytes,

including

(1)

bacterial products,

(2)

cytokines, especially those of the chemokine family;

(3)

components of the complement system, particularly C5a; and C3a

.These mediators are produced in response to infections and tissue damage and

during immunologic reactions. Leukocyte infiltration in all these situations results

from the actions of various combinations of mediators.

Leukocyte Effector Mechanisms

Leukocytes can eliminate microbes and dead cells by phagocytosis, followed by

their destruction in phagolysosomes. Destruction is caused by free radicals (ROS,

NO) generated in activated leukocytes and lysosomal enzymes. Enzymes and ROS

may be released into the extracellular environment. The mechanisms that function

to eliminate microbes and dead cells (the physiologic role of inflammation) are

also capable of damaging normal tissues (the pathologic consequences of

inflammation).

Phagocytosis

Phagocytosis of a particle (e.g., a bacterium) involves (1) attachment and binding

of the particle to receptors on the leukocyte surface, (2) engulfment and fusion of

the phagocytic vacuole with granules (lysosomes), and (3) destruction of the

ingested particle. NOS, Inducible nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; ROS,

reactive oxygen species.

Outcome of acute inflammation

1.Resolution.

When the injury is limited or short-lived, when there has been no or minimal tissue

damage, and when the tissue is capable of replacing any irreversibly injured cells,

the usual outcome is restoration to histologic and functional normalcy.

2.Progression to chronic inflammation

may follow acute inflammation if the offending agent is not removed. In some

instances, signs of chronic inflammation may be present at the onset of injury (e.g.,

in viral infections or immune responses to self-antigens). Depending on the extent

of the initial and continuing tissue injury, as well as the capacity of the affected

tissues to regrow, chronic inflammation may be followed by restoration of normal

structure and function or may lead to scarring.

3. Scarring or fibrosis

results after substantial tissue destruction or when inflammation occurs in tissues

that do not regenerate. In addition, extensive fibrinous exudates (due to increased

vascular permeability) may not be completely absorbed and are organized by

ingrowth of connective tissue, with resultant fibrosis.

4. Abscesses

may form in the setting of extensive neutrophilic infiltrates or in certain bacterial

or fungal infections (these organisms are then said to be pyogenic, or "pus

forming"). Because of the underlying tissue destruction (including damage to the

ECM), the usual outcome of abscess formation is scarring.