Definition of healing DR. LAMIEA ALL LECTURES OF HEALING

The word healing refers to the body replaced the destroyed tissue by living tissue.

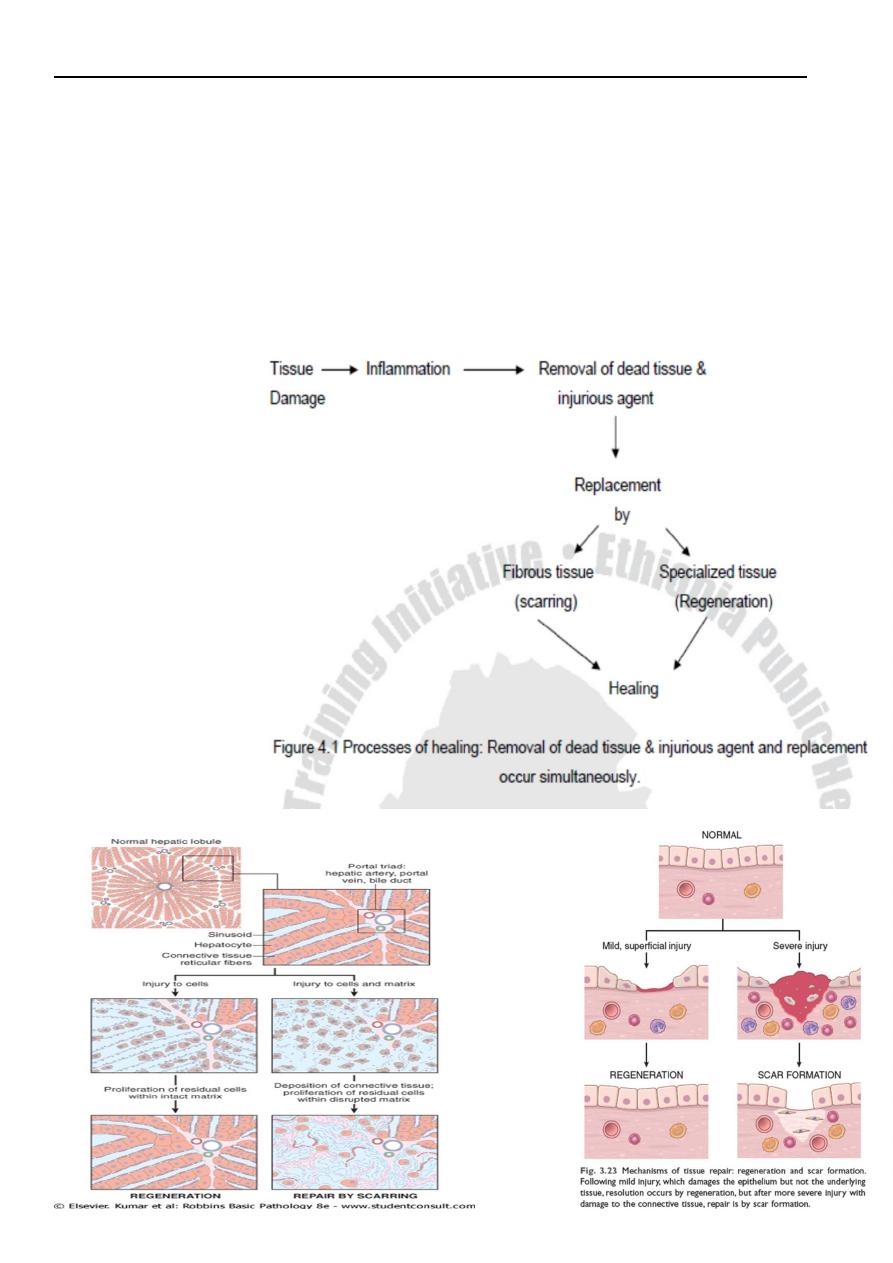

III. Processes of healing

The healing involves two distinct processes:

Regeneration, the replacement of lost tissue by tissues similar in type

Repair (healing by scaring), the replacement of lost tissue by granulation tissue which

matures to form scar tissue.

Healing by fibrosis is inevitable when the surrounding specialized cells do not possess the

capacity to proliferate.

Whether healing takes place by regeneration or

by repair (scarring) is determined partly by the

type of cells in the damaged organ & partly by

the destruction or the intactness of the stromal

frame work of the organ. Hence, it is important

to know the types of cells in the body.

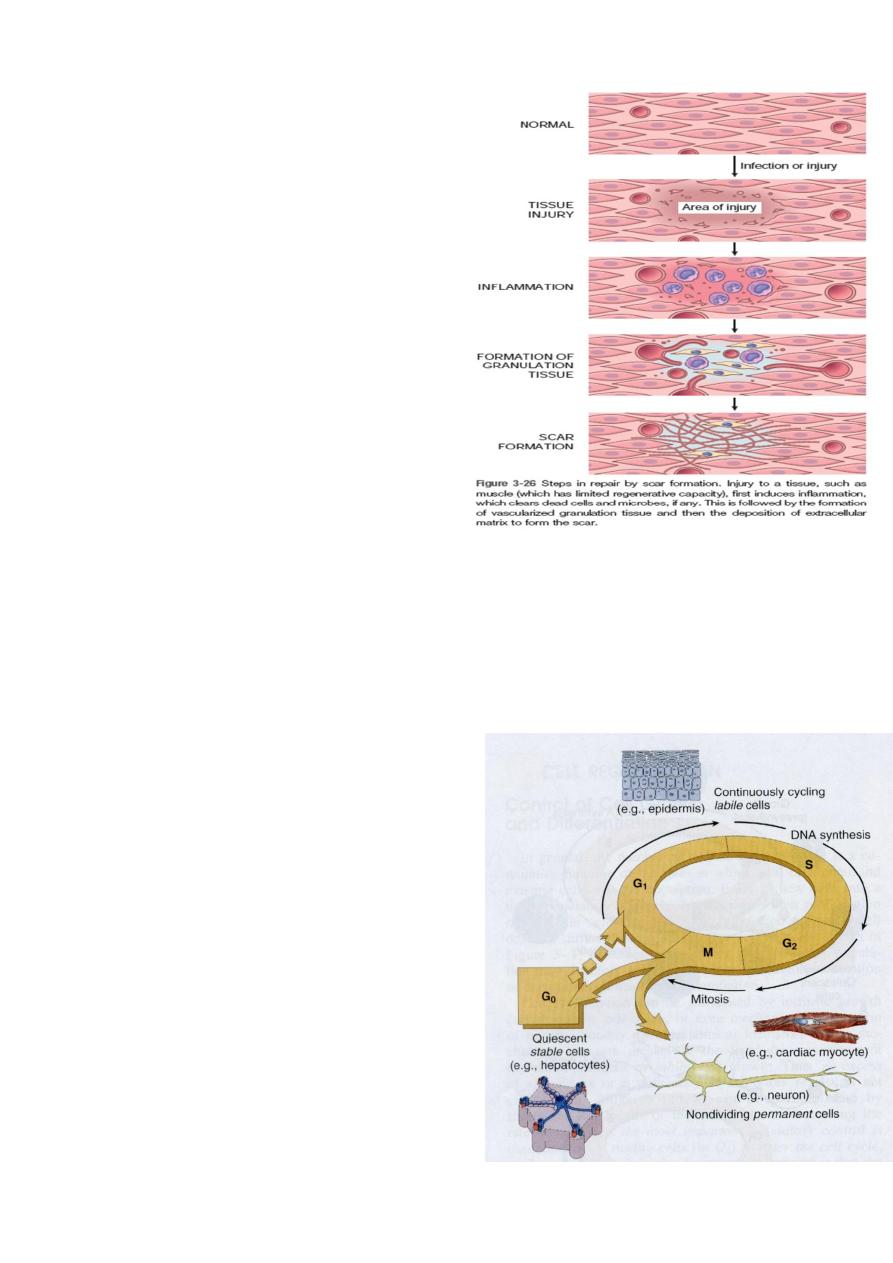

Types of cells

Based on their proliferative capacity there are

three types of cells.

1. Labile cells

These are cells which have a continuous turn over by programmed division of stem cells.

They are found in the surface epithelium of the gastrointestinal treat, urinary tract or the skin.

The cells of lymphoid and haemopoietic systems are further examples of labile cells. The

chances of regeneration are excellent

2. Stable cells (Quiescent cells)

Tissues which have such type of cells have

normally a much lower level of replication and

there are few stem cells. However, the cells of

such tissues can undergo rapid division in

response to injury. For example, mesenchymal

cells such as smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts,

osteoblasts and endothelial cells are stable cells

which can proliferate. Liver, endocrine glands

and renal tubular epithelium has also such type of

cells which can regenerate. Their chances of

regeneration are good.

3. Permanent cells

These are non-dividing cells. If lost, permanent

cells cannot be replaced, because they don not have the capacity to proliferate. For example:

adult neurons, striated muscle cells, and cells of the lens. Having been introduced to the

types of cells, we can go back to the two types of healing processes & elaborate them.

Cell types and cell cycle phases

Constantly dividing labile cells continuously cycling from one mitosis to the next.

Nondividing permanent cells have exited the cycle and are distended to die without

further division. Quiescent stable cells in G0 are neither cycling nor dying and can be

induced to re-enter the cycle by an appropriative stimulus.

a. Healing by regeneration

Definition: Regeneration (generare=bring to life) is the renewal of a lost tissue in which the

lost cells are replaced by identical ones.

Regeneration involves two processes

1. Proliferation of surviving cells to replace lost tissue

2. Migration of surviving cells into the vacant (empty) space.

The capacity of a tissue for regeneration depends on its

1) proliferative ability,

2) degree of damage to stromal framework and

3) on the type and severity of the damage.

Tissues formed of labile and stable cells can regenerate provided that stromal frame work are

intact.

b. Repair (Healing by connective tissue)

Definition:- Repair is the orderly process by which lost tissue is eventually replaced by a

scar.

A wound in which only the lining epithelium is affected heals exclusively by regeneration. In

contrast, wounds that extend through the basement membrane to the connective tissue, for

example, the dermis in the skin or the sub-mucosa in the gastrointestinal tract, lead to the

formation of granulation tissue and eventual scarring.

Tissues containing terminally differentiated (permanent) cells such as neurons and skeletal

muscle cells can not heal by regeneration. Rather the lost permanent cells are replaced by

formation of granulation tissue.

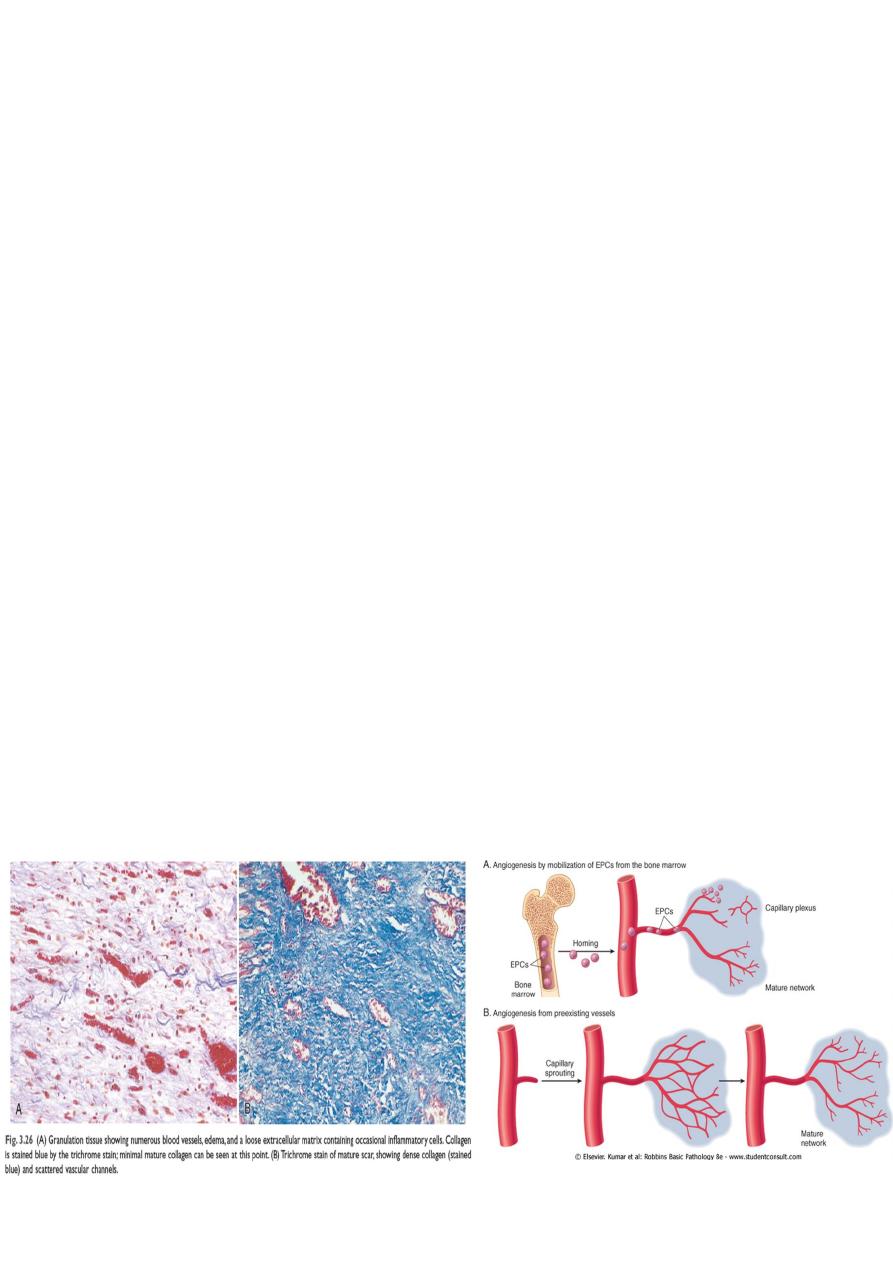

In granulation-tissue formation, three phases may be observed.

1. Phase of inflammation

At this phase, inflammatory exudate containing polymorphs is seen in the area of tissue

injury. In addition, there is platelet aggregation and fibrin deposition.

2. Phase of demolition

The dead cells liberate their autolytic enzymes, and other enzymes (proteolytic) come from

disintegrating polymorphs. There is an associated macrophage infiltration. These cells ingest

particulate matter, either digesting or removing it.

3. In growth of granulation tissue

This is characterized by proliferation of fibroblasts and an in growth of new blood vessels

into the area of injury, with a variable number of inflammatory cells.

Fibroblasts actively synthesize and secrete extra-cellular matrix components, including

fibronectin, proteoglycans, and collagen types I and III. The fibronectin and proteoglycans

form the ‘scaffolding’ for rebuilding of the matrix. Fibronectin binds to fibrin and acts as a

chemotactic factor for the recruitment of more fibroblasts and macrophages.

The synthesis of collagen by fibroblasts begins within 24 hours of the injury although its

deposition in the tissue is not apparent until 4 days. By day 5, collagen type III is the

predominant matrix protein being produced; but by day 7 to 8, type I is prominent, and it

eventually becomes the major collagen of mature scar tissue. This type I collagen is

responsible for providing the tensile strength of the matrix in a scar.

Coincident with fibroblast proliferation there is angiogenesis (neovascularization), a

proliferation and formation of new small blood vessels. Vascular proliferation starts 48 to 72

hours after injury and lasts for several

days.

With further healing, there is an increase in extracellular constituents, mostly collagen, with

a decrease in the number of active fibroblasts and new vessels. Despite an increased

collagenase activity in the wound (responsible for removal of built collagen), collagen

accumulates at a steady rate, usually reaching a maximum 2 to 3 months after the injury.

The tensile strength of the wound continues to increase many months after the

collagen content has reached a maximum. As the collagen content of the wound

increases, many of the newly formed vessels disappear. This vascular involution which takes

place in a few weeks, dramatically transforms a richly vascularized tissue in to a pale,

avascular scar tissue.

Wound contraction

Wound contraction is a mechanical reduction in the size of the defect. The wound is reduced

approximately by 70-80% of its original size. Contraction results in much faster healing,

since only one-quarter to one-third of the amount of destroyed tissue has to be replaced. If

contraction is prevented, healing is slow and a large ugly scar is formed.

Causes of contraction

It is said to be due to contraction by myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts have the features

intermediate between those of fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. Two to three days after

the injury they migrate into the wound and their active contraction decrease the size of the

defect.

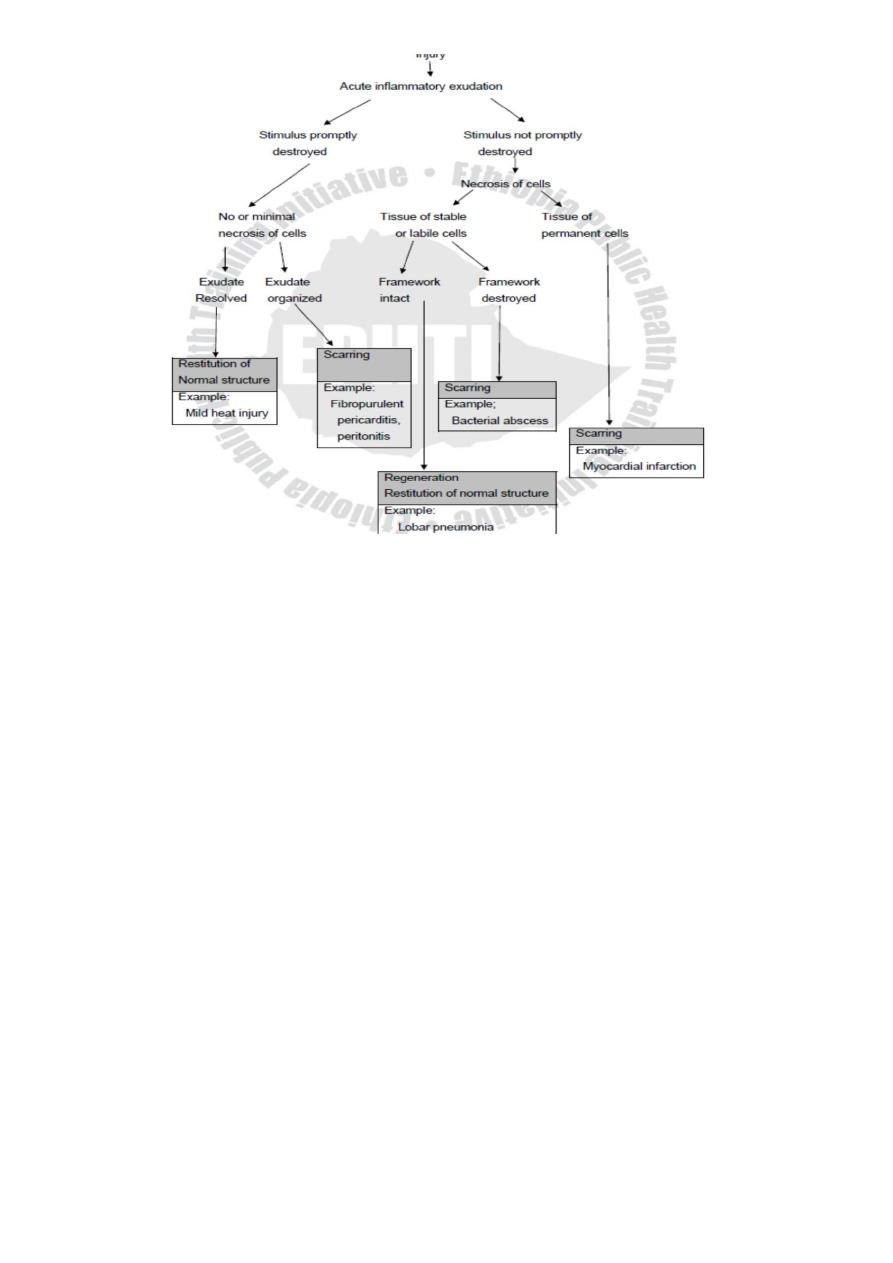

Summary

Following tissue injury, whether healing occurs by regeneration or scarring is determined by

the degree of tissue destruction, the capacity of the parenchymal cells to proliferate, and the

degree of destructon of stromal framework as illustrated in the diagram below (See Fig. 4.2).

In the above discussion, regeneration, repair, and contraction have been dealt with

separately. Yet they are not mutually exclusive processes. On the contrary, the three

processes almost invariably participate together in wound healing.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………….

Figure 4.2 Diagram showing healing process following acute inflammatory injury

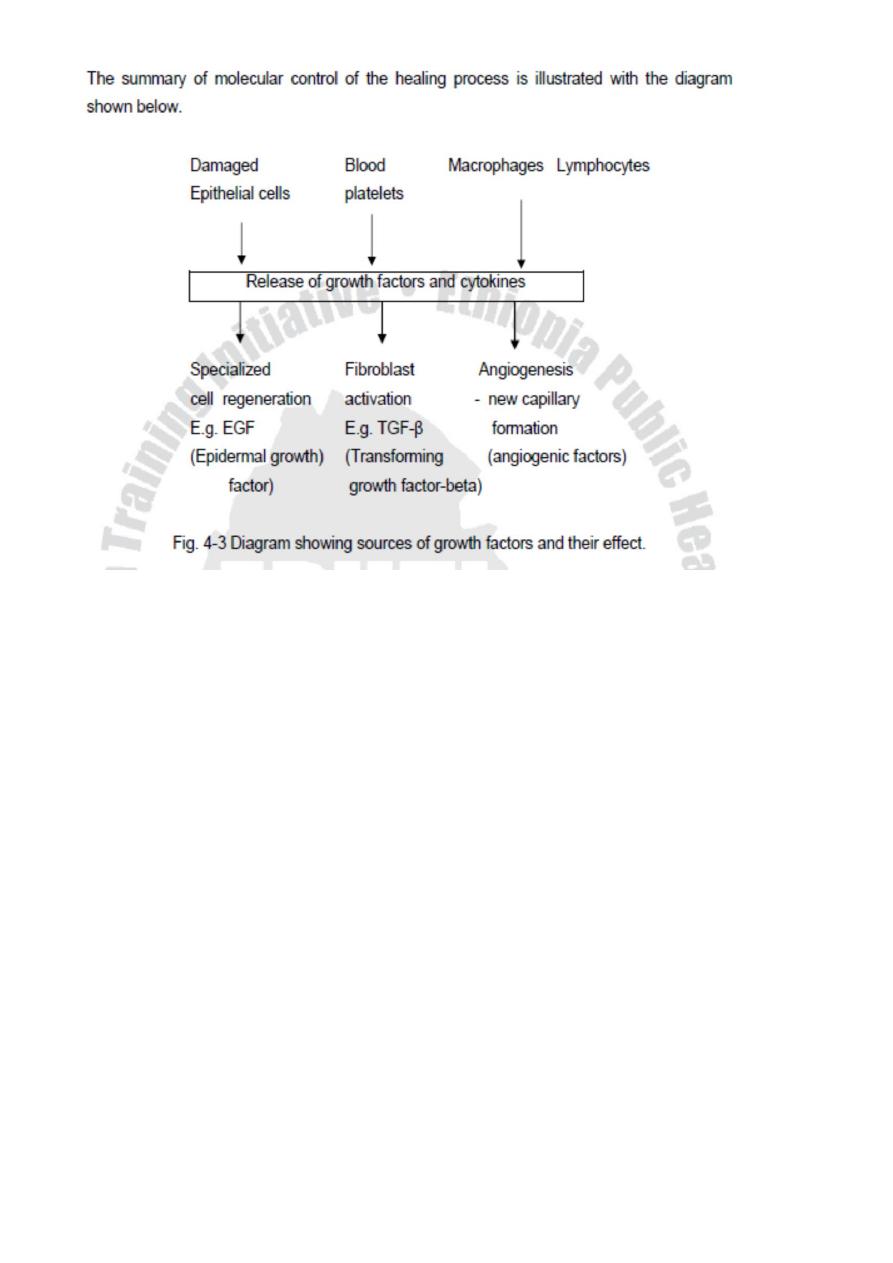

IV. Molecular control of healing process

As seen above, healing involves an orderly sequence of events which includes regeneration

and migration of specialized cells, angiogenesis, proliferation of fibroblasts and related cells,

matrix protein synthesis and finally cessation of these processes. These processes, at least in

part, are mediated by a series of low molecular weight polypeptides referred to as growth

factors.

These growth factors have the capacity to stimulate cell division and proliferation. Some of

the factors, known to play a role in the healing process, are briefly discussed below.

Sources of Growth Factors:

Following injury, growth factors may be derived from a number of sources such as:

1. Platelets, activated after endothelial damage,

2. Damaged epithelial cells,

3. Circulating serum growth factors,

4. Macrophages, or

5. Lymphocytes recruited to the area of injury

The healing process ceases when lost tissue has been replaced. The mechanisms

regulating this process are not fully understood. TGF-β acts as a growth inhibitor for both

epithelial and endothelial cells and regulates their regeneration.

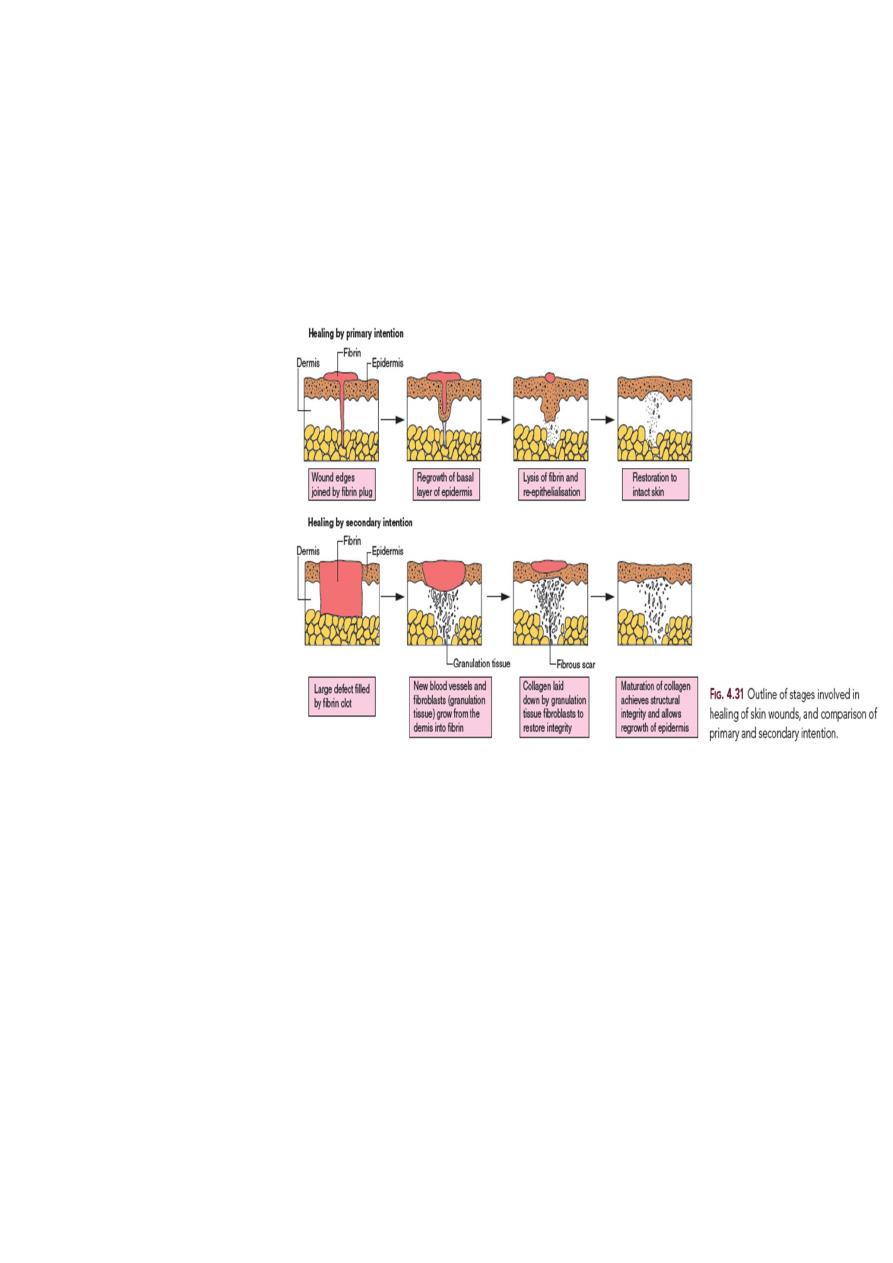

VI. Wound Healing

The two processes of healing, described above, can occur during healing of a diseased organ

or during healing of a wound. A wound can be accidental or surgical. Now, we will discuss

skin wound healing to demonstrate the two basic processes of healing mentioned above.

Healing of a wound demonstrates both epithelial regeneration (healing of the epidermis) and

repair by scarring (healing of the dermis).

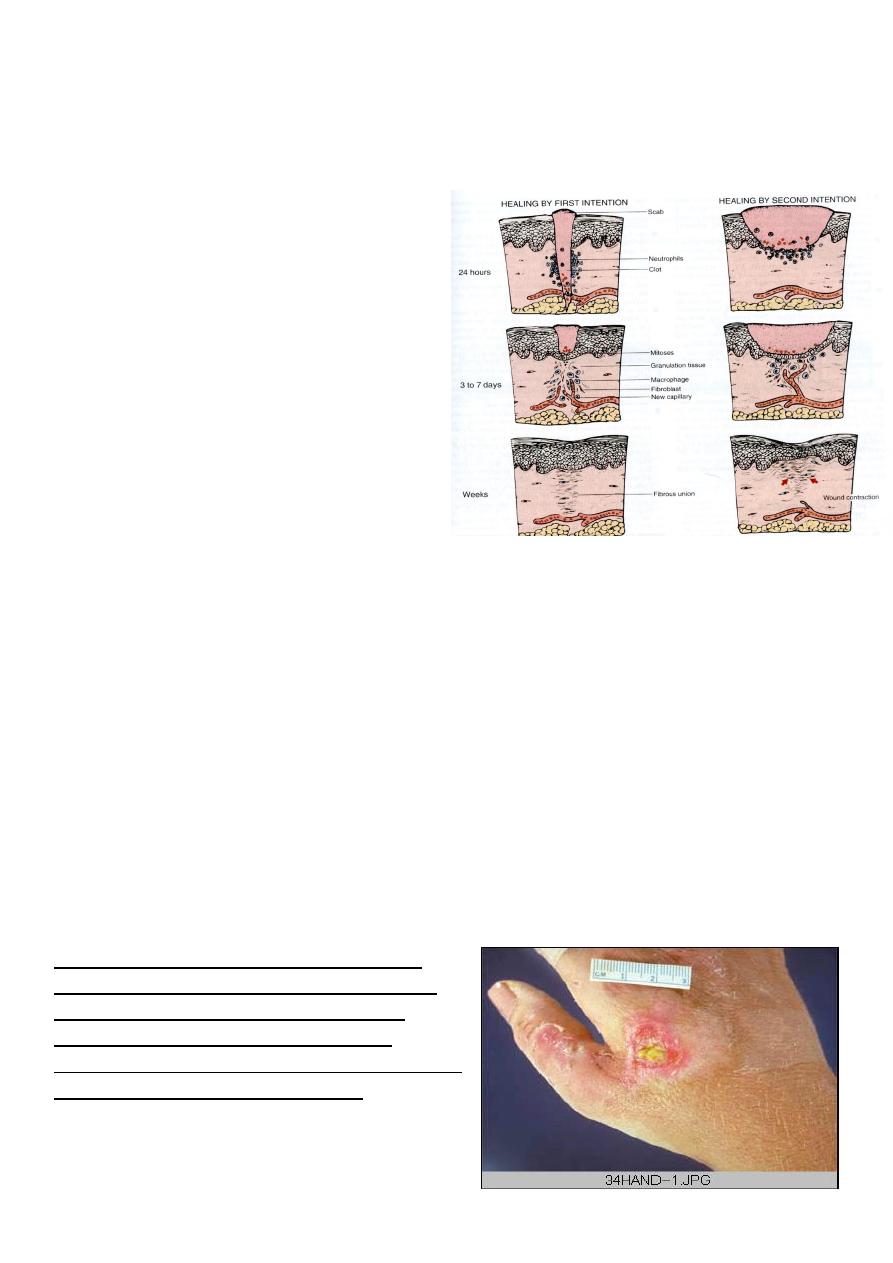

There are two patterns of wound healing depending on the amount of tissue damage:

1. Healing by first intention (Primary union)

2. Healing by second intention

These two patterns are essentially the same process varying only in amount.

1. Healing by first intention (primary union)

The least complicated example of wound healing is the healing of a clean surgical incision

(Fig. 4-4, left). The wound edges are approximated by surgical sutures, and healing occurs

with a minimal loss of tissue. Such healing is referred to, surgically, as “primary union” or

“healing by first intention”. The incision causes the death of a limited number of epithelial

cells as well as of dermal adnexa and connective tissue cells; the incisional space is narrow

and immediately fills with clotted blood, containing fibrin and blood cells; dehydration of

the surface clot forms the well-known scab that covers the wound and seals it from the

environment almost at once.

Within 24 hours, neutrophils appear at the margins of the incision, moving toward the fibrin

clot. The epidermis at its cut edges thickens as a result of mitotic activity of basal cells and,

within 24 to 48 hours, spurs of epithelial cells from the edges both migrate and grow along

the cut margins of the

dermis and beneath the

surface scab to fuse in the

midline, thus producing a

continuous but thin

epithelial layer.

By day 3, the neutrophils

have been largely

replaced by macrophages.

Granulation tissue

progressively invades the

incisional space. Collagen

fibers are now present in

the margins of the

incision, but at first these

are vertically oriented and do not bridge the incision.

Epithelial cell proliferation continues, thickening the epidermal covering layer.

By day 5, the incisional space is filled with granulation tissue. Neovascularization is

maximal. Collagen fibrils become more abundant and begin to bridge the incision.

The epidermis recovers its normal thickness and differentiation of surface cells yields a

mature epidermal architecture with surface keratinization.

During the second week, there is continued accumulation of collagen and proliferation of

fibroblasts. Leukocytic infiltrate, edema, and increased vascularity have largely disappeared.

At this time, the long process of blanching begins, accomplished by the increased

accumulation of collagen within the incisional scar, accompanied by regression of vascular

channels.

By the end of the first month, the scar comprises a cellular connective tissue devoid of

inflammatory infiltrate, covered now by an intact epidermis. The dermal appendages that

have been destroyed in the line of the incision are permanently lost.

Tensile strength of the wound increases thereafter, but it may take months for the wounded

area to obtain its maximal strength.

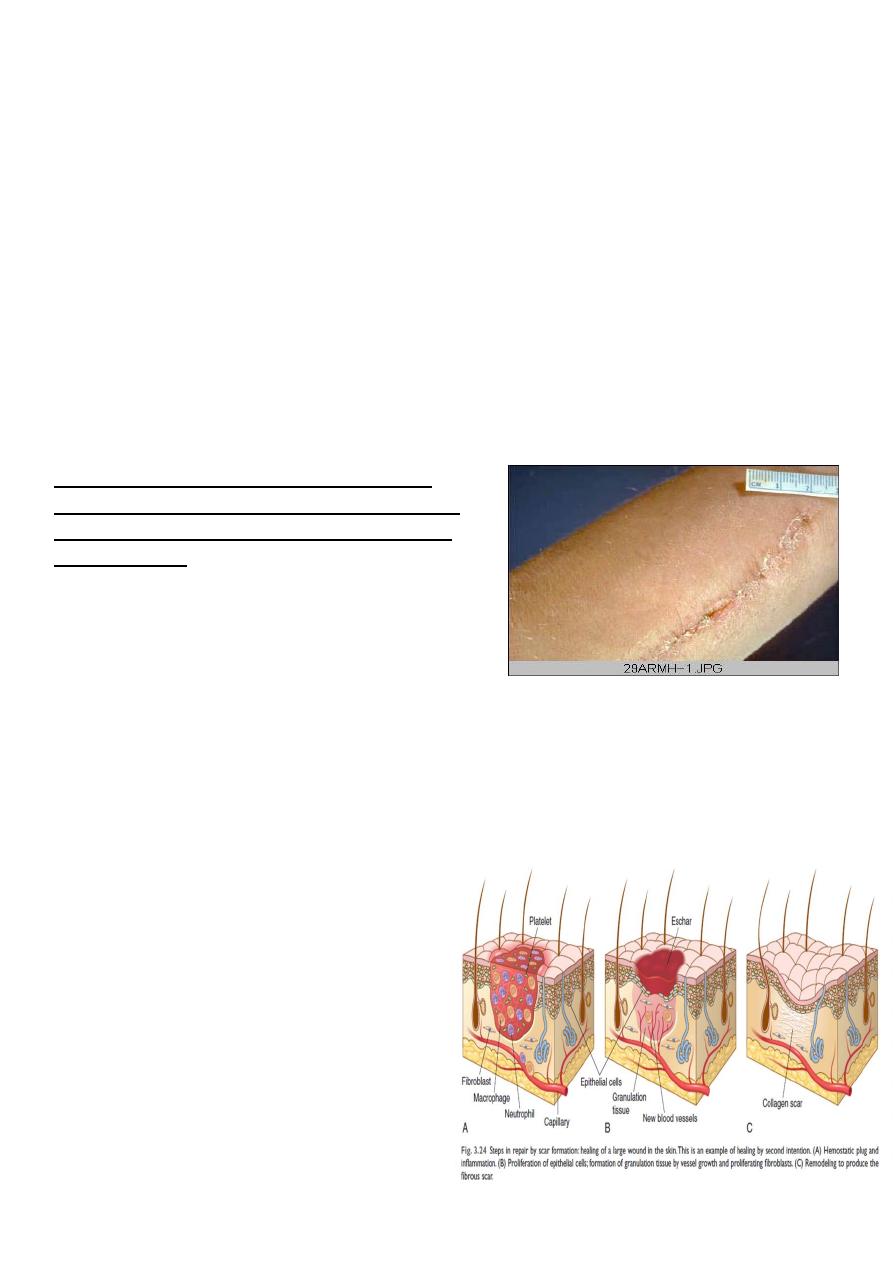

Arm, healing surgical incision. This image

demonstrates healing by first intention which

occur in clean, un infected wounds that have

apposed edges.

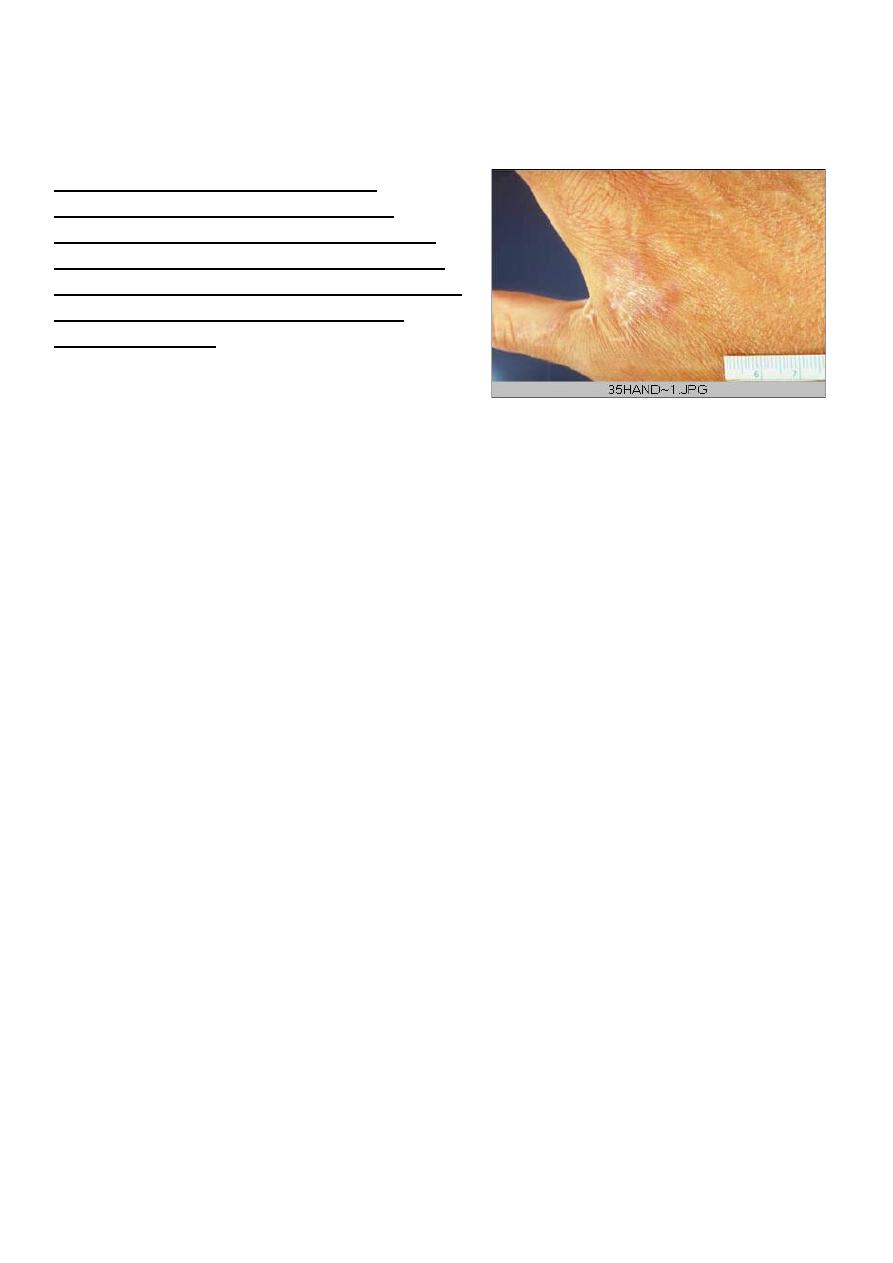

2. Healing by second intention (secondary union)

When there is more extensive loss of cells

and tissue, such as occurs in infarction,

inflammatory ulceration, abscess

formation, and surface wounds that create

large defects, the reparative process is

more complicated. The common

denominator in all these situations is a

large tissue defect that must be filled.

Regeneration of parenchymal cells cannot

completely reconstitute the original

architecture. Abundant granulation tissue

grows in from the margin to complete the

repair. This form of healing is referred to

as “secondary union” or “healing by second intention.”

Secondary healing differs from primary healing in several respects:

Wound healing by primary and secondary

union

1. Inevitably, large tissue defects initially have more fibrin and more necrotic debris and

exudate that must be removed. Consequently, the inflammatory reaction is more intense.

2. Much larger amounts of granulation tissue are formed. When a large defect occurs in

deeper tissues, such as in a viscus, granulation tissue bears the responsibility for its closure,

because drainage to the surface cannot occur.

3. Perhaps the feature that most clearly differentiates primary from secondary healing is the

phenomenon of wound contraction, which occurs in large surface wounds.

4. Healing by second intention takes much longer than when it occurs by first

intention.

Wound with large tissue defect healed by

secondary intention. Note the red granular

appearance of the granulation tissue. A

whitish- greenish- yellow neutrophilic

exudates represent an inflammatory response

to bacterial invasion of the wound.

Hand healed by secondary intention

As the granulation tissue matures, the

myofibroblast contract to close the wound.

They then become mature fibroblast, which

produce collagen, forming a fibrous scar. The

contraction that takes place can lead to

decrease mobility.

VI. Factors that influence wound healing

A number of factors can alter the rate and efficiency of healing. These can be classified in to

those which act locally, and those which have systemic effects. Most of these factors have

been established in studies of skin wound healing but many are likely to be of relevance to

healing at other sites.

• Type, size, and location of the wound

A clean, aseptic wound produced by the surgeon’s scalpel heals faster than a wound

produced by blunt trauma, which exhibits aboundant necrosis and irregular edges. Small

blunt wounds heal faster than larger ones. Injuries in richly vascularized areas (e.g., the face)

heal faster than those in poorly vascularized ones (e.g., the foot). In areas where the skin

adheres to bony surfaces, as in injuries over the tibia, wound contraction and adequate

apposition of the edges are difficult. Hence, such wounds heal slowly.

• Vascular supply

Wounds with impaired blood supply heal slowly. For example, the healing of leg wounds in

patients with varicose veins is prolonged. Ischemia due to pressure produces bed sores and

then prevents their healing. Ischemia due to arterial obstruction, often in the lower

extremities of diabetics, also prevents healing.

• Infection

Wounds provide a portal of entry for microorganisms. Infection delays or prevents healing,

promotes the formation of excessive granulation tissue (proud flesh), and may result in large,

deforming scars.

• Movement

Early motion, particularly before tensile strength has been established, subjects a wound to

persistent trauma, thus preventing or retarding healing.

• Ionizing radiation

Prior irradiation leaves vascular lesions that interfere with blood supply and result in slow

wound healing. Acutely, irradiation of a wound blocks cell proliferation, inhibits contraction,

and retards the formation of granulation tissue.

Systemic Factors

• Circulatory status

Cardiovascular status, by determining the blood supply to the injured area, is important for

wound healing. Poor healing attributed to old age is often due, largely, to impaired

circulation.

• Infection

Systemic infections delay wound healing.

• Metabolic status

Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus is associated with delayed wound healing. The risk of

infection in clean wound approaches five fold the risk in non- diabetics.

In diabetic patients, there can be impaired circulation secondary to arteriosclerosis and

impaired sensation due to diabetic neuropathy. The impaired sensation renders the lower

extremity blind to every day hazards. Hence, in diabetic patients, wounds heal the very

slowly.

• Nutritional deficiencies

Protein deficiency

In protein depletion there is an impairment of granulation tissue and collagen formation,

resulting in a great delay in wound healing.

Vitamine deficiency

Vitamin C is required for collagen synthesis and secretion. It is required in hydroxylation of

proline and lysine in the process of collagen synthesis. Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) results

in grossly deficient wound healing, with a lack of vascular proliferation and collagen

deposition.

Trace element deficiency

Zinc (a co-factor of several enzymes) deficiency will retard healing by preventing cell

proliferation. Zinc is necessary in several DNA and RNA polymerases and transferases;

hence, a deficiency state will inhibit mitosis. Proliferation of fibroblasts (fibroplasia) is,

therefore, retarded.

• Hormones

Corticosteroids impair wound healing, an effect attributed to an inhibition of collagen

synthesis. However, these hormones have many other effects, including anti-inflammatory

actions and a general depression of protein synthesis. It also inhibits fibroplasia and

neovascularization. Both epithelialization and contraction are impaired. It is, therefore,

difficult to attribute their inhibition of wound healing to any one specific mechanism.

Thyroid hormones, androgens, estrogens and growth hormone also influence wound

healing. This effect, however, may be more due to their regulation of general metabolic

status rather than to a specific modification of the healing process.

• Anti-inflammatory drugs

Anti-inflammatory medications do not interfere with wound healing when administered at

the usual daily dosages. Asprin and indomethalin both inhibit prostaglandin synthesis and

thus delay healing.

VII. Complications of Wound Healing

Abnormalities in any of the three basic healing processes – contraction, repair, and

regeneration – result in the complications of wound healing.

1. Infection

A wound may provide the portal of entry for many organisms. Infectrion may delay

healing, and if severe stop it completely.

2. Deficient Scar Formation

Inadequate formation of granulation tissue or an inability to form a suitable extracellular

matrix leads to deficient scar formation and its complications. The complications of deficient

scar formation are:

a. Wound dehiscence & incitional hernias

b. Ulceration

a. Wound Dehiscence and Incisional Hernias:

Dehiscence (bursting of a wound) is of most concern after abdominal surgery. If insufficient

extracellular matrix is deposited or there is inadequate cross-linking of the matrix, weak

scars result. Dehiscence occurs in 0.5% to 5% of abdominal operations. Inappropriate suture

material and poor surgical techiniques are important factors. Wound infection, increased

mechanical stress on the wound from vomiting, coughing, or ileus is a factor in most cases of

abdominal dehiscence. Systemic factors that predispose to dehiscence include poor

metabolic status, such as vitamin C deficiency, hypoproteinemia, and the general inanition

that often accompanies metastatic cancer. Dehiscence of an abdominal wound can be a life

threatening complication, in some studies carrying a mortality as high as 30%. An incisional

hernia, usually of the abdominal wall, refers to a defect caused by poor wound healing

following surgery into which the intestines protrude.

b. Ulceration:

Wounds ulcerate because of an inadequate intrinsic blood supply or insufficient

vascularization during healing. For example, leg wounds in persons with varicose veins or

severe atherosclerosis typically ulcerate. Non healing wounds also develop in areas devoid of

sensation because of persistent trauma. Such trophic or neuropathic ulcers are occasionally

seen in patients with leprosy, diabetic peripheral neuropathy and in tertiary syphilis from

spinal involvement (in tabes dorsalis).

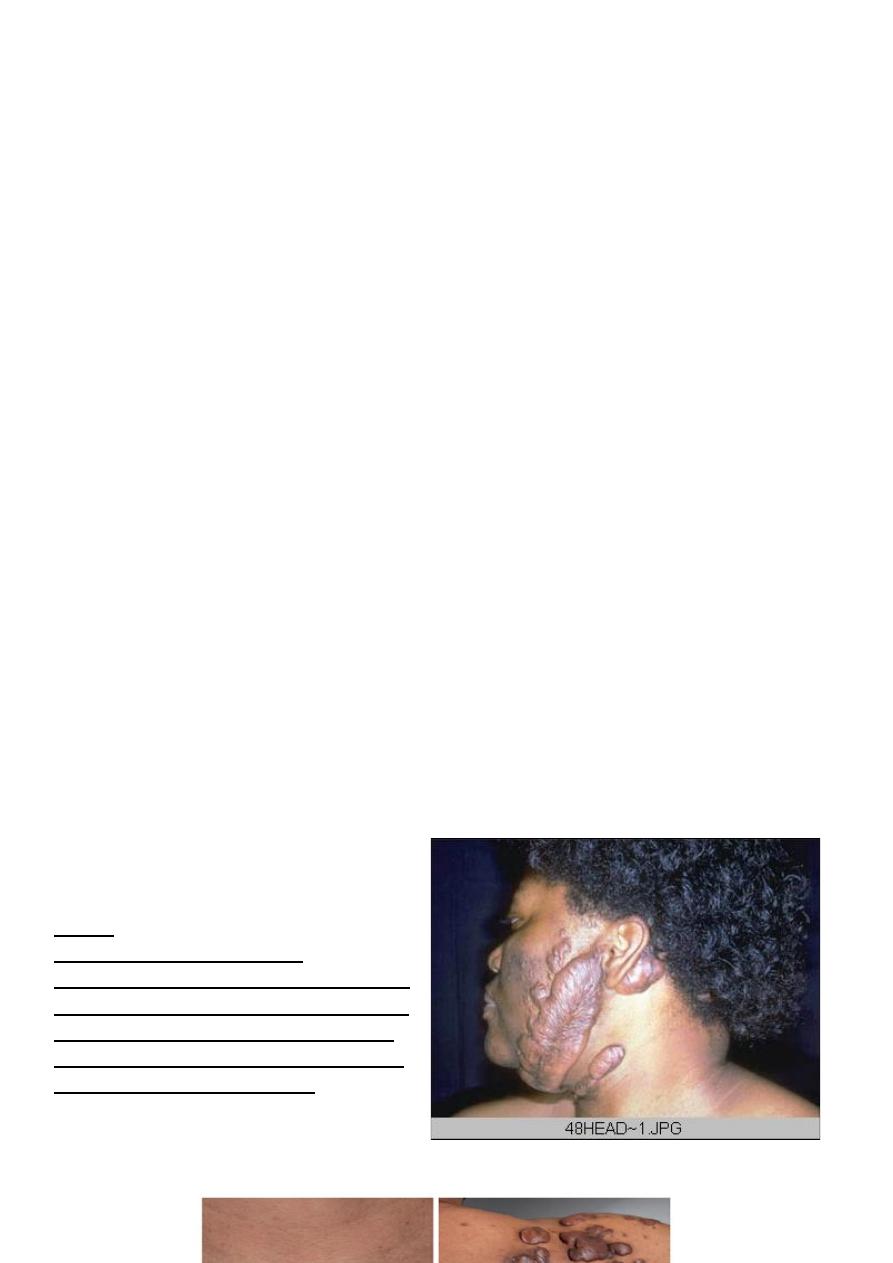

3. Excessive Scar Formation

An excessive deposition of extracellular matrix at the wound site results in a hypertrophic

scar or a keloid (See Figure 4-5 and 4-6). The rate of collagen synthesis, the ratio of type III

to type I collagen, and the number of reducible cross-links remain high, a situation that

indicates a “maturation arrest”, or block, in the healing process.

Keloid Formation

An excessive formation of collagenous tissue results in the appearance of a raised area of

scar tissue called keloid. It is an exuberant scar that tends to progress and recur after

excision. The cause of this is unknown. Genetic predisposition, repeated trauma, and

irritation caused by foreign body, hair, keratin, etc., may play a part. It is especially frequent

after burns. It is common in areas of the neck & in the ear lobes.

Hypertrophic Scar

Hypertrophic scar is structurally similar to keloid. However, hypertrophic scar never gets

worse after 6 months unlike keloid, which gets worse even after a year and some may even

progress for 5 to 10 years. Following excision keloid recurres, whereas a hypertrophic scar

does not.

Keloid

Keloid nodular masses of of

hyperplastic scar tissue, occur when the

wound healing process runs unchecked.

They are more commonly in people of

African descent. surgical excision leads

to repeated keloid formation.

4. Excessive contraction

A decrease in the size of a wound depends on the presence of myofibroblasts, development

of cell-cell contacts and sustained cell contraction. An exaggeration of these processes is

termed contracture (cicatrisation) and results in severe deformity of the wound and

surrounding tissues. Contracture (cicatrisation) is also said to arise as a result of late

reduction in the size of the wound. Interestingly, the regions that normally show minimal

wound contraction (such as the palms, the soles, and the anterior aspect of the thorax) are the

ones prone to contractures. Contractures are particularly conspicuous in the healing of

serious burns.

Contractures of the skin and underlying connective tissue can be severe

enough to compromise the movement of joints. Cicatrisation is also important in hollow

viscera such as urethra, esophagus, and intestine. It leads to progressive stenosis with

stricture formation. In the alimentary tract, a contracture (stricture) can result in an

obstruction to the passage of food in the esophagus or a block in the flow of intestinal

contents.

5. Miscellaneous

Implantation (or epidermoid cyst: Epithelial cells which flow into the healing wound may

later sometimes persist, and proliferate to form an epidermoid cyst.

VIII. Fracture Healing

The basic processes involved in the healing of bone fractures bear many resemblances to

those seen in skin wound healing. Unlike healing of a skin wound, however, the defect

caused by a fracture is repaired not by a fibrous “scar” tissue, but by specialized bone

forming tissue so that, under favorable circumstances, the bone is restored nearly to normal.

Structure of bone

Bone is composed of calcified osteoid tissue, which consists of collagen fibers embedded in

a mucoprotein matrix (osteomucin). Depending on the arrangement of the collagen fibers,

there are two histological types of bone:

1. Woven, immature or non-lamellar bone This shows irregularity in the arrangement

of the collagen bundles and in the distribution of the osteocytes. The osseomucin

is less abundant and it also contains less calcium.

2. Lamellar or adult bone In this type of bone, the collagen bundles are arranged in

parallel sheets.

Stages in Fracture Healing (Bone Regeneration)

Stage 1: Haematoma formation. Immediately following the injury, there is a variable

amount of bleeding from torn vessels; if the periosteum is torn, this blood may

extend into the surrounding muscles. If it is subsequently organized and ossified,

myositis ossificans results.

Stage 2: Inflammation. The tissue damage excites an inflammatory response, the exudates

adding more fibrin to the clot already present. The inflammatory changes differ in no way

from those seen in other inflamed tissues. There is an increased blood flow and a

polymorphonuclear leucocytic infiltration. The haematoma attains a fusiform shape.

Stage 3: Demolition. Macrophages invade the clot and remove the fibrin, red cells, the

inflammatory exudate, and debris. Any fragments of bone, which have become

detached from their blood supply, undergo necrosis, and are attacked by

macrophages and osteoclasts.

Stage 4: Formation of granulation tissue. Following this phase of demolition, there is an

ingrowth of capillary loops and mesenchymal cells derived from the periosteum

and the endosteum of the cancellous bone. These cells have osteogenic potential

and together with the newly formed blood vessels contribute to the granulation –

tissue formation.

Stage 5: Woven bone and cartilage formation. The mesenchymal “osteoblasts” next

differentiate to form either woven bone or cartilage. The term “callus”, derived

from the Latin and meaning hard, is often used to describe the material uniting the

fracture ends regardless of its consistency. When this is granulation tissue, the

“callus” is soft, but as bone or cartilage formation occurs, it becomes hard.

Stage 6: Formation of lamellar bone. The dead calcified cartilage or woven bone is next

invaded by capillaries headed by osteoclasts. As the initial scaffolding

(“provisional callus”) is removed, osteoblasts lay down osteoid, which calcifies to

form bone. Its collagen bundles are now arranged in orderly lamellar fashion, for

the most part concentrically around the blood vessels, and in this way the

Haversian systems are formed. Adjacent to the periosteum and endosteum the

lamellae are parallel to the surface as in the normal bone. This phase of formation

of definitive lamellar bone merges with the last stage.

Stage 7: Remodelling. The final remodeling process involving the continued osteoclastic

removal and osteoblastic laying down of bone results in the formation of a bone, which

differs remarkably little from the original tissue. The external callus is slowly removed, the

intermediate callus becomes converted into compact bone

containing Haversian systems, while the internal callus is hollowed out into a

marrow cavity in which only a few spicules of cancellous bone remain.

Thank You