The gall bladder andbile ducts

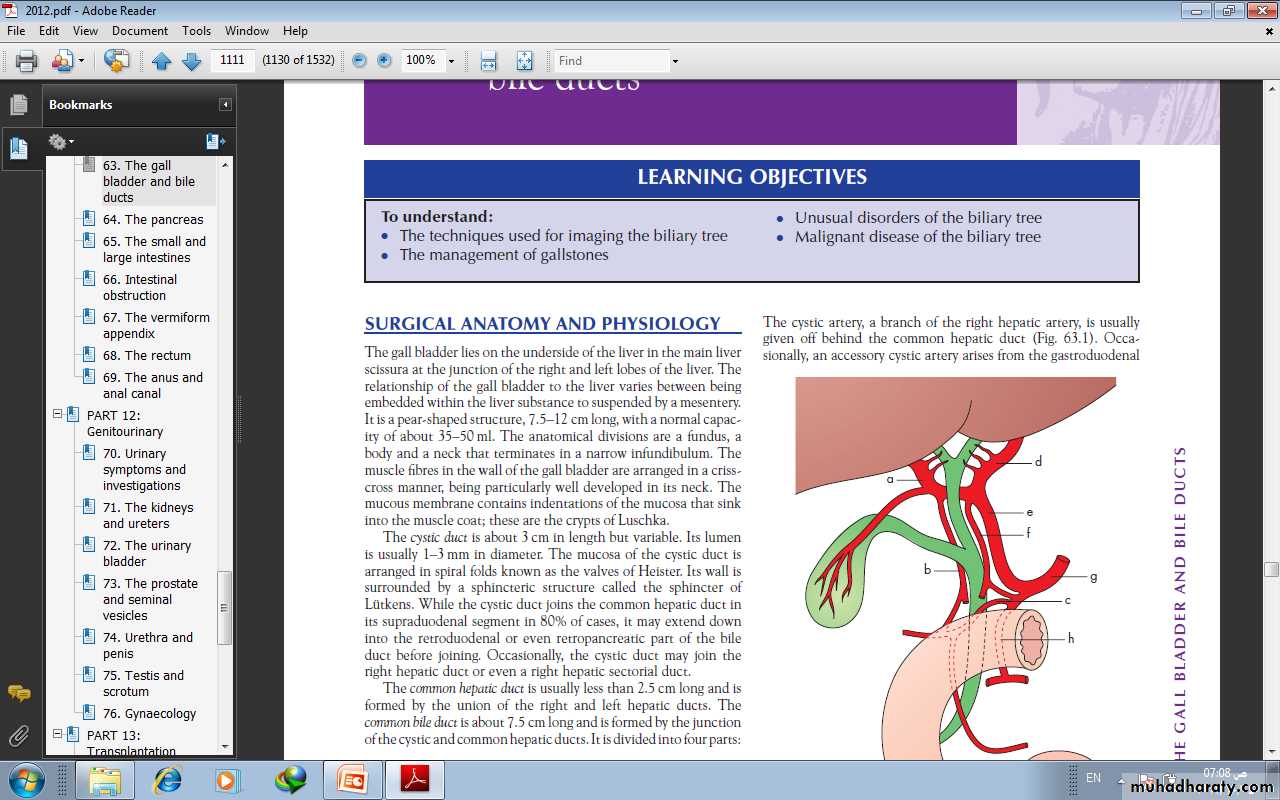

Surgical anatomy The gall bladder lies on the underside of the liver at the junction of the right and left lobes of the liver. The relationship of the gall bladder to the liver varies between being embedded within the liver substance to suspended by a mesentery. it is a pear-shaped structure, 7.5–12 cm long, with a normal capacityof about 35–50 ml. The anatomical divisions are a fundus, a body and a neck that terminates in a narrow infundibulum..The cystic duct is about 3 cm in length but variable. Its lumenis usually 1–3 mm in diameter. Its wall is surrounded by a sphincteric structure called the sphincter of Lütkens. While the cystic duct joins the common hepatic duct in its supraduodenal segment in 80% of cases, it may extend down into the retroduodenal or even retropancreatic part of the bileduct before joining.

The common hepatic duct is usually less than 2.5 cm long and isformed by the union of the right and left hepatic ducts. Thecommon bile duct is about 7.5 cm long and is formed by the junctionof the cystic and common hepatic ducts. It is divided into four parts:• the supraduodenal portion, about 2.5 cm long, • the retroduodenal portion;• the infraduodenal portion, on the posterior surface of the pancreas;• the intraduodenal portion, which passes obliquely through thewall of the second part of the duodenum, where it is surroundedby the sphincter of Oddi, and terminates by openingon the ampulla of Vater.

The cystic artery, a branch of the right hepatic artery, Occasionally,. In 15% of cases, the right hepatic artery and/or the cysticartery cross in front of the common hepatic duct and the cysticduct. The most dangerous anomalies are where the hepatic arterytakes a tortuous course on the front of the origin of the cysticduct, or the right hepatic artery is tortuous and the cystic arteryshort. The tortuosity is known as the ‘caterpillar turn’ .

LymphaticsThe lymphatic vessels of the gall bladder drain into the cystic lymph node of Lund . This lies in the fork created by the junction of the cystic and common hepatic ducts. The subserosal lymphatic vessels of the gall bladder also connect with the subcapsular lymph channels of the liver.

Surgical physiologyBile, as it leaves the liver, is composed of 97% water, 1–2% bilesalts and 1% pigments, cholesterol and fatty acids. The liverexcretes bile at a rate estimated to be approximately 40 ml h–1.The rate of bile secretion is controlled by cholecystokinin (CCK),which is released from the duodenal mucosa. With feeding, thereis increased production of bile.

FUNCTIONS OF THE GALL BLADDERThe gall bladder is a reservoir for bile. During fasting, resistance toflow through the sphincter is high, and bile excreted by the liver isdiverted to the gall bladder.The second main function of the gall bladder is concentrationof bile by active absorption of water, sodium chloride and bicarbonateby the mucous membrane of the gall bladder.The third function of the gall bladder is the secretion of mucus– approximately 20 ml is produced per day.

RADIOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION OF THEBILIARY TRACTPlain radiographA plain radiograph of the gall bladder will show radio-opaquegallstones in 10% of patients with gallstones . Rarely,the centre of a stone may contain radiolucent gas ‘Mercedes-Benz’ sign in the A plain X-ray may also show the rare cases of calcification ofthe gall bladder, a so called ‘porcelain’ gall bladder .The importance of this appearance is an association with carcinomain up to 25% of patients. Gas may be seen in the wall of the gall bladder(emphysematous cholecystitis). Gas in the biliary tree may be seen after endoscopic sphincterotomy or surgical anastomosis Oral cholecystography and intravenouscholangiographyOral and intravenous cholecystography are of historical interest only .

UltrasonographyTransabdominal ultrasonography is the initialimaging modality of choice as it is accurate, readily available,inexpensive and quick to perform. However, it is operatordependent and may be suboptimal due to excessive body fat andintraluminal bowel gas. It can demonstrate biliary calculi, the sizeof the gall bladder, the thickness of the gall bladder wall, the presence of inflammation around the gall bladder, the size of thecommon bile duct and, occasionally, the presence of stones withinthe biliary tree..

In the patient who presents with obstructive jaundice, ultrasonography can identify- intra- and extrahepatic biliary dilatation and the level of obstruction.- the cause of the obstruction may also be identified, such as gallstones in the gall bladder, common hepatic or common bile duct stones or lesions in the wall of the duct suggestive of acholangiocarcinoma or enlargement of the pancreatic headEndoscopic ultrasonography uses a specially designed endoscope with an ultrasound transducer at its tip, which allows visualisation of the liver and biliary tree from within the stomach and duodenum. it useful in detecting stones within the bile ducts( choledocholithiasis). In addition, it has been shown to be highly accurate in diagnosing and staging both pancreatic and periampullary cancers.

Radioisotope scanning (scintigraphy ) Technetium-99m (99mTc)-labelled derivatives of iminodiaceticacid (HIDA scan ) when injected intravenously, selectivelytaken up by the retroendothelial cells of the liver andexcreted into bile. This allows visualisation of the biliary tree andgall bladder. Non-visualisation of the gallbladder is suggestive of acute cholecystitis. If the patient has acontracted gall bladder, as often occurs in chronic cholecystitis,gall bladder visualisation may be reduced or delayed.Biliary scintigraphy may also be helpful in diagnosing bile leaksand iatrogenic biliary obstruction. When there is a suspicion of abile leak following a cholecystectomy, radioisotope imagingshould be performed.

Computerised tomographyThis imaging modality allows visualisation of the liver, bile ducts,gall bladder and pancreas. It is particularly useful in detectinghepatic and pancreatic lesions and is the modality of choice inthe staging of cancers of the liver, gall bladder, bile ducts andpancreas. It can identify the extent of the primary tumour anddefines its relationship to other organs and blood vessels . In addition, the presence of enlarged lymph nodes ormetastatic disease can be seen.For benign biliary diseases, computerised tomography is not that useful an investigation. Gallstones are usually not visualised Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. It is non-invasive , Contrast is not required and, excellent images can be obtained of the biliary tree that demonstrate ductal obstruction, strictures or other intraductal abnormalities.

Endoscopic retrogradecholangiopancreatographyThis technique remains widely used. Using a side-viewing endoscope,the ampulla of Vater can be identified and cannulated.Injection of water-soluble contrast directly into the bile ductprovides excellent images of the ductal anatomy andcan identify causes of obstruction such as stones ormalignant strictures , Bile can be sent for cytological and microbiological examination, and brushings can be taken from strictures for cytological studies. Therapeutic interventions such as stone removal or stent placement to relieve the obstructioncan be performed. Thus, ERCP has evolved into a mainly therapeutic rather than a diagnostic uses .

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiographyThis is an invasive technique in which the bile ducts are cannulated directly. It is only done once a bleeding tendency has been excluded, Antibiotics should be given prior to the procedure. Usually,, a needle is introduced percutaneously into the liver substance. Under radiological control (either ultrasound or CT), a bile duct is cannulated. Successful entry is confirmed by aspiration of bile. Water-soluble contrast medium is injected to demonstrate the biliary system. In addition, PTC enables the placement of a catheter into the bile ducts to provide external biliary drainage or the insertion of stents.

Peroperative cholangiographyDuring open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy, a catheter can beplaced in the cystic duct and contrast injected directly into thebiliary tree. The technique defines the anatomy and is mainlyused to exclude the presence of stones within the bile ducts .

Operative biliary endoscopy (choledochoscopy)At operation, a flexible fibreoptic endoscope can be passed downthe cystic duct into the common bile duct enabling stone identification and removal under direct vision. After exploration of the bile duct, a tube can be left in the cystic duct remnant or in the common bile duct (a T-tube) and drainage of the biliary tree established. After 7–10 days, a track will be established. This track can be used for the passage of a choledochoscope to remove residual stones .

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES OF THEGALL BLADDER AND BILE DUCTSEmbryologyAbsence of the gall bladderOccasionally, the gall bladder is absent. Failure to visualise thegall bladder is not necessarily a pathological problem.The Phrygian capThe Phrygian cap is present in 2–6% and may be mistaken for a pathological deformity of the organ. ‘Phrygian cap’ refers to hats worn by the people of Phrygia.

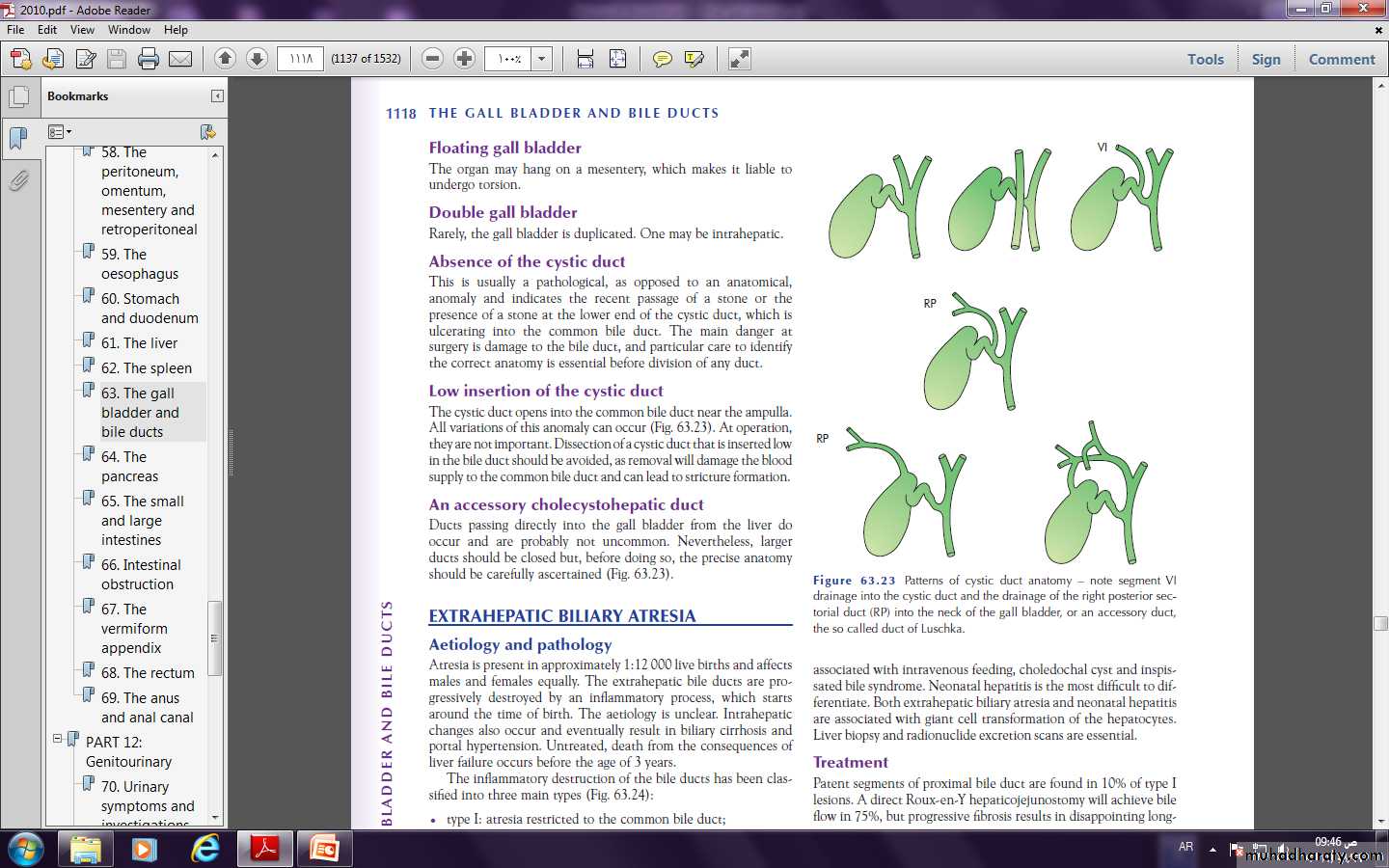

Floating gall bladderThe organ may hang on a mesentery, which makes it liable toundergo torsion.Double gall bladderRarely, the gall bladder is duplicated.Absence of the cystic ductThis is usually a pathological, anomaly and indicates the recent passage of a stone or thepresence of a stone at the lower end of the cystic duct, which is ulcerating into the common bile duct. The main danger at surgery is damage to the bile duct.Low insertion of the cystic ductThe cystic duct opens into the common bile duct near the ampulla.All variations of this anomaly can occur .An accessory cholecystohepatic ductDucts passing directly into the gall bladder from the liver dooccur .

EXTRAHEPATIC BILIARY ATRESIAAetiology and pathologyAtresia is uncommon affects males and females equally. The extrahepatic bile ducts are progressively destroyed by an inflammatory process, which startsaround the time of birth. eventually result in biliary cirrhosis andportal hypertension. Untreated, death from the consequences ofliver failure occurs before the age of 3 years.The inflammatory destruction of the bile ducts has been classifiedinto three main types• type I: atresia restricted to the common bile duct;• type II: atresia of the common hepatic duct;• type III: atresia of the right and left hepatic ducts.

Clinical featuresAbout one-third of patients are jaundiced at birth. In all, however,jaundice is present by the end of the first week and deepensprogressively. The meconium may be a little bile-stained, butlater the stools are pale and the urine is dark. Pruritus is severe. Clubbing and skin xanthomas.Differential diagnosisThis includes any form of jaundice in a neonate giving a cholestaticpicture. Examples are alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, cholestasisassociated with intravenous feeding, choledochal cyst and inspissated bile syndrome. Neonatal hepatitis is the most difficult to differentiate.Liver biopsy and radioisotope scans are essential

TreatmentPatent segments of proximal bile duct are found in 10% of type Ilesions. A direct Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy will achieve bileflow in 75%, but progressive fibrosis results in disappointing long term results. A simple biliary–enteric anastomosis is not possiblein the majority of cases in which the proximal hepatic ducts areeither very small (type II) or atretic (type III). These are treatedby the Kasai procedure. Liver transplantation should be considered in children in whom a portoenterostomy is unsuccessful Postoperative complications include bacterial cholangitis. Repeated attacks lead to hepatic fibrosis, portal hypertension, with one-third having variceal bleeding.

CONGENITAL DILATATION OF THEINTRAHEPATIC DUCTS (CAROLI’S DISEASE)This rare condition is characterised by multiple irregular sacculardilatations of the intrahepatic ducts with a normal extrahepatic biliary system. The aetiology is unknown, but it is considered to behereditary. It can be divided into a simple and a periportal fibrotictype. The periportal fibrotic type presents in childhood and isassociated with biliary stasis, stone formation and cholangitis. Incontrast, the simple type presents later with episodes of abdominalpain and biliary sepsis. Associated conditions include congenital hepatic fibrosis, polycystic liver treatment are antibiotics for the cholangitis and the removal of calculi, lobectomy may be indicated.

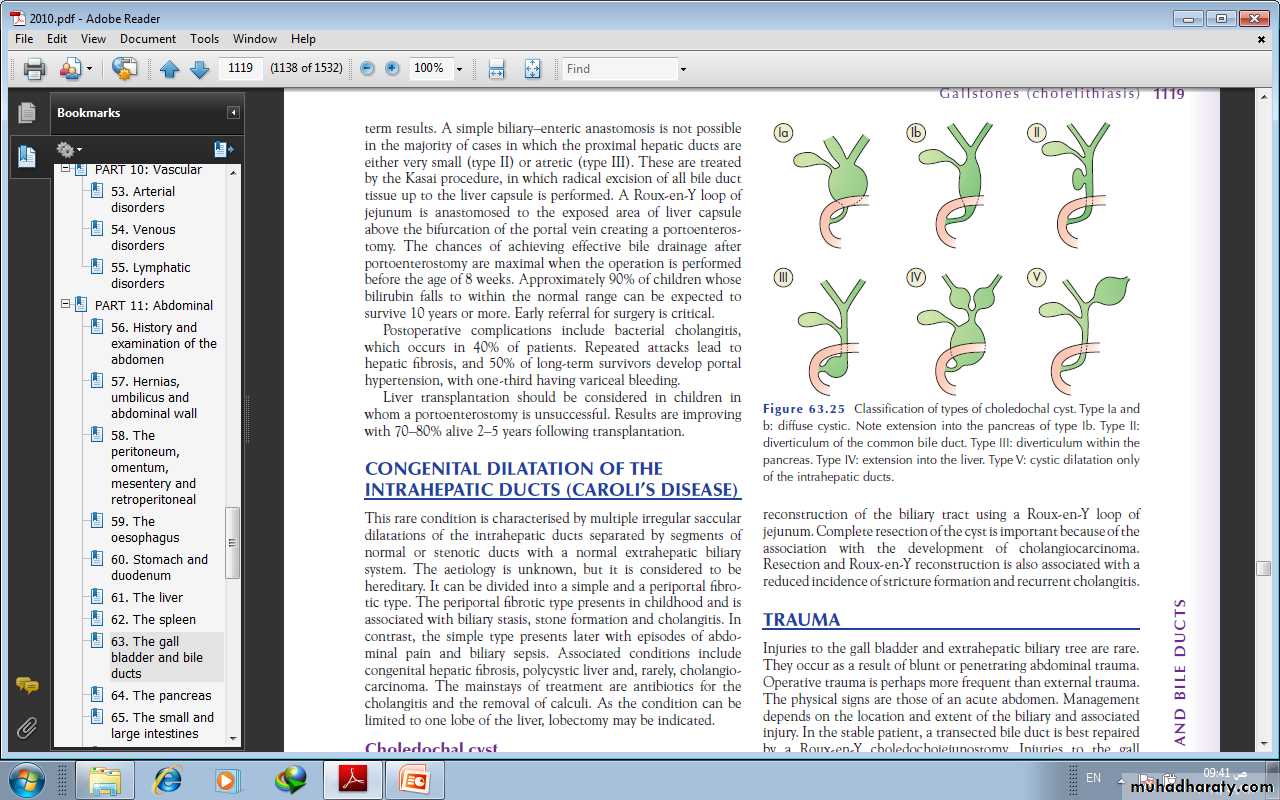

Choledochal cyst Choledochal cysts are congenital dilatations of the intra- and/or extrahepatic biliary system. The pathogenesis is unclear. Type I cysts are the most common 75% of patients.Patients may present at any age with jaundice, fever, abdominalpain and a right upper quadrant mass on examination. Pancreatitisis a not infrequent presentation in adults. Patients with choledochal cysts have an increased risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma .Ultrasonography will confirm the presence of an abnormalcyst and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI/MRCP) will revealthe anatomy, CT is also useful for the extent of the intra- or extrahepatic dilatation.

Type Ia and b: diffuse cystic. Note extension into the pancreas of type Ib. Type II:diverticulum of the common bile duct. Type III: diverticulum within thepancreas. Type IV: extension into the liver. Type V: cystic dilatation onlyof the intrahepatic ducts.

Radical excision of the cyst is the treatment of choice withreconstruction of the biliary tract using a Roux-en-Y loop ofjejunum. Complete resection of the cyst is important because of the association with the development of cholangiocarcinoma.

TRAUMAInjuries to the gall bladder and extrahepatic biliary tree are rare.They occur as a result of blunt or penetrating abdominal trauma.Operative trauma is perhaps more frequent than external trauma.The physical signs are those of an acute abdomen. Management. In the stable patient, a transected bile duct is best repaired by a Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy. Injuries to the gallbladder can be dealt with by cholecystectomy.TORSION OF THE GALL BLADDERThis occurs mostly in an older patient with a large mucocele of the gall bladder. patient presents with an acute abdomen.Immediate exploration and cholecystectomy are indicated.

GALLSTONES (CHOLELITHIASIS)Gallstones are the most common biliary pathology. It is estimated that gallstones are present in 10–15% of the adult population in the USA. They are asymptomatic in the majority (> 80%). Approximately 1–2% of asymptomatic patients will develop symptoms requiring cholecystectomyAetiology of gallstonesGallstones can be divided into three main types:1. cholesterol2.pigment (brown/black) 3.mixed stones. 80% are cholesterol or mixed stones, whereas in Asia, 80% arepigment stones. Cholesterol or mixed stones contain cholesterol plus an admixture of calcium salts, bile acids, bile pigments and phospholipids

pathogenesis1- bile is supersaturated with Cholesterol or bile acid concentrations are low, unstable phospholipid vesicles form, from which cholesterol crystals may nucleate, and stones may form. 2- Obesity, high-calorie diets and certain medications can increase the secretion of cholesterol and supersaturate bile, increasing the lithogenicity of bile.3- Abnormal emptying of the gall bladder may promote the aggregation of cholesterol crystals; hence, removing gallstones without removing the gall bladder inevitably leads to gallstone recurrence.

Pigment stone is the name used for stones containing less than30% cholesterol. There are two types – black and brown. Blackstones are largely composed of an insoluble bilirubin pigment mixed with calcium phosphate and calcium bicarbonate. Black stone associated with haemolysis, usually hereditary spherocytosis or sickle cell disease. For unclear reasons, patients with cirrhosis have a higher instance of pigmented stones. Brown stones are rare in the gall bladder. They form in the bile duct and are related to bile stasis and infected bile.

Clinical presentationPatients typically complain of right upper quadrant or epigastricpain, which may radiate to the back. This may be described ascolicky, but more often is dull and constant. Other symptomsinclude dyspepsia, flatulence, food intolerance, particularly tofats, and some alteration in bowel frequency. Biliary colic is typically present in 10–25% of patients. associated withnausea and vomiting. Pain may radiate to the chest. The pain isusually severe and may last for minutes or even several hours.Frequently, the pain starts during the night, waking the patient.Dyspeptic symptoms may coexist and be worseafter such an attack. As the pain resolves, the patient is able toeat and drink again,

When symptoms do not resolve, but progress to continued painwith fever and leucocytosis, the diagnosis of acute cholecystitisshould be considered.

• Effects and complications of gallstonesIn the gallbladder Asymtomatic Biliary colic Acute cholecystitis Chronic cholecystitis Empyema of the gall bladder Mucocele PerforationIn the bile ducts Biliary obstruction Acute cholangitis Acute pancreatitisIn the intestine Intestinal obstruction (gallstone ileus)

Differential diagnosis of cholecystitisCommon Appendicitis Perforated peptic ulcer Acute pancreatitisUncommon Acute pyelonephritis Myocardial infarction Pneumonia – right lower lobe

DiagnosisA diagnosis of gallstone disease is based on the history andphysical examination . In the acute phase, the patient may have right upperquadrant tenderness that is exacerbated during inspiration by theexaminer’s right subcostal palpation (Murphy’s sign). A positiveMurphy’s sign suggests acute inflammation and may be associatedwith a leucocytosis and moderately elevated liver function tests. A mass may be palpable as the omentum walls off aninflamed gall bladder. Fortunately, the process is limited because stone is slipped back to gall bladder. If resolution does not occur, an empyema of the gall bladdermay result. The wall may become necrotic and perforate, with thedevelopment of localised peritonitis. The abscess may then perforateinto the peritoneal cavity with a generlised peritonitis

A palpable, non-tender gall bladder (Courvoisier’s sign) usually results from a distal common duct obstruction secondary to a pancreatic malignancy.Rarely, a non-tender, palpable gall bladder results fromcomplete obstruction of the cystic duct with reabsorption of theintraluminal bile salts and secretion of uninfected mucussecreted by the gall bladder epithelium, leading to a mucocele ofthe gall bladder.

Treatmentit is safe to observe patients with asymptomatic gallstones, with cholecystectomy only being performedfor those patients who develop symptoms or complications . However, prophylactic cholecystectomyshould be considered in diabetic patients, those with congenitalhaemolytic anaemia and those due to undergo bariatric surgeryfor morbid obesity.For patients with biliary colic or cholecystitis, cholecystectomyis the treatment of choice in the absence of medical contraindications.The timing of surgery in acute cholecystitis remains controversial. Many favour early operation , whereasothers suggest that a delayed approach is preferable.

Conservative treatment followed by cholecystectomy more than 90% of cases, the symptoms of acute cholecystitis subside with conservative measures. Nonoperative treatment is :1 Nil by mouth (NPO) and intravenous fluid administration.2 Administration of analgesics.3 Administration of antibiotics. As the cystic duct is blocked inmost instances, the concentration of antibiotic in the serum ismore important than its concentration in bile. A broadspectrumantibiotic effective against Gram-negative aerobes ismost appropriate (e.g. cefazolin, cefuroxime or gentamicin).4 Subsequent management. When the temperature, pulse andother physical signs show that the inflammation is subsiding,oral fluids are reinstated followed by regular diet. Ultrasonographyis performed . Cholecystectomy may be performed on the next available list.

Routine early operation operation is undertaken within 5–7 days of the onset of the attack, the surgeon is experienced and excellent operating facilities. If an early operation is not indicated, should wait 6 weeks for the inflammation to subside before proceeding to operate.

EMPYEMA OF THE GALL BLADDERThe gall bladder appears to be filled with pus. It may be a sequelof acute cholecystitis or the result of a mucocele becominginfected. The treatment is drainage and, later, cholecystectomy.Acalculous cholecystitisAcute and chronic inflammation of the gall bladder can occur inthe absence of stones and give rise to a clinical picture similar tocalculous cholecystitis.Acute acalculous cholecystitis is seen particularly inpatients recovering from major surgery (e.g. coronary arterybypass), trauma and burns. In these patients, the diagnosis isoften missed, and the mortality rate is high

THE CHOLECYSTOSES (CHOLESTEROSIS,POLYPOSIS, ADENOMYOMATOSIS ANDCHOLECYSTITIS GLANDULARISPROLIFERANS)This is a not uncommon group of conditions affecting the gallbladder, in which there are chronic inflammatory changes withhyperplasia of all tissue elements.Cholesterosis (‘strawberry gall bladder’)In the fresh state, the interior of the gall bladder looks somethinglike a strawberryCholesterol polyposis of the gall bladderCholecystography shows negative shadows in a functioning gallbladder, or there is a well-defined polyp present on ultrasound. surgery is advised only if they change in size or are longerthan 1 cm.

Cholecystitis glandularis proliferans (polyp,adenomyomatosis and intramural diverticulosis)A polyp of the mucous membrane is fleshy and granulomatous. All layersof the gall bladder wall may be thickened, but sometimesan incomplete septum forms that separates the hyperplasticfrom the normal. Intraparietal ‘mixed’ calculi may be present.These can be complicated by an intramural, and later extramural,abscess. If symptomatic, the patient is treated by cholecystectomy.Diverticulosis of the gall bladderDiverticulosis of the gall bladder is usually manifest as black pigmentstones impacted in the outpouchings in the wall of gall bladder . Diverticulosis of the gall bladder may be demonstratedby cholecystography, especially when the gall bladder contractsafter a fatty meal. There are small dots of contrast medium justwithin and outside the gall bladder . The treatment is cholecystectomy

CHOLECYSTECTOMYPreparation for operationAn appropriate history is taken, and the patient’s fitness forthe procedure is assessed. This includes investigation of thecardiovascular and respiratory systems, and a full blood countand biochemical are performed to exclude anaemia orabnormal liver function. Blood coagulation is checked if thereis a history of jaundice. The patient is given prophylactic antibioticseither with pre-medication or at the time of anaestheticinduction. A second-generation cephalosporin isappropriate. Subcutaneous heparin or anti-embolic stockingsare prescribed. Informed consent should be taken .

Laparoscopic cholecystectomyThe preparation and indications for cholecystectomy are thesame whether it is performed by laparoscopy or by open techniques.Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the procedure of choicefor the majority of patients with gall bladder disease . Serious complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy fall intotwo major areas: access complications or bile duct injuries. In themain, access complications occur during the insertion of theVerres needle to establish pneumoperitoneum or the insertion oftrocars. If insertion is performed blindly or is found to be difficult,visceral injury should be excluded. If either a visceral or a bileduct injury is suspected, conversion to an open technique isrecommended by most surgeons.

Open cholecystectomyFor patients in whom a laparoscopic approach is not indicated orin whom conversion from a laparoscopic approach is required, anopen cholecystectomy is performed. A cholecystostomy is rarely indicated but, if necessary, as manystones as possible should be extracted, and a large Foley catheter(14F) placed in the fundus of the gall bladder with a direct trackexternally.

Indications for choledochotomy1-palpable stones in the common bile duct;2- jaundice, a history of jaundice or cholangitis;3- a dilated common bile duct;4- abnormal liver function tests, in particular a raised alkalinephosphatase.

‘post-cholecystectomy’ syndromecholecystectomy fails to relieve the symptomsfor which the operation was performed. Such patients may be considered. However, such problems are usually related to the preoperative symptoms and are merely a continuation of those symptoms. Full investigation should be undertaken to confirm the diagnosis and exclude the presence of a stone in the common bile duct, a stone in the cystic duct stumpor operative damage to the biliary tree. Management is best performed by MRCP or ERCP.

Management of bile duct obstruction followingcholecystectomyIncidence of bile duct injury is 0.05%Patients with symptoms developing either immediately or delayedafter a cholecystectomy, particularly if jaundice is present, needurgent investigation. This is especially true if the jaundice is associatedwith infection, a condition called cholangitis. The first step in management is to do ultrasound scan. This will demonstrate whether there is intra- or extrahepatic ductal dilatation. The anatomy needs to be defined by either an ERCP or an MRCP. The latter investigation will alsoallow for therapeutic manoeuvres such as removal of an obstructingstone or insertion of a stent across a biliary leak. If a fluid collectionis present in the subhepatic space, drainage catheters maybe required.

the injury declares itself postoperativelyby: (1) a profuse and persistent leakage of bile ifdrainage has been provided, or bile peritonitis if such drainagehas not been provided; and (2) deepening obstructive jaundice.

TreatmentIn the debilitated patient, temporary external biliary drainagemay be achieved by passing a catheter percutaneously into anintrahepatic duct. Also, stents may be passed through stricturesat the time of ERCP and left to drain into the duodenum. When the general condition of the patient has improved, definitive surgery can be undertaken, Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy by an experienced surgeon. For a stricture of recent onset through which a guidewire can be passed, balloon dilatation with insertion of a stent is an acceptable alternative.

Stones in the bile ductDuct stones may occur many years after a cholecystectomy or be related to the development of new pathology, suchas infection of the biliary tree or infestation by Ascaris lumbricoidesor Clonorchis sinensis. Any obstruction to the flow of bile can giverise to stasis with the formation of stones within the duct. Theconsequence of duct stones is either obstruction to bile flow orinfection. Stones in the bile ducts are more often associated withinfected bile (80%)

SymptomsThe patient is often ill and feels unwell. The term ‘cholangitis’ is given to the triad of pain, jaundice and fevers, sometimes known as ‘Charcot’s triad’.SignsTenderness may be elicited in the epigastrium and the righthypochondrium. In the jaundiced patient, it is useful to rememberCourvoisier’s law – in obstruction of the common bile ductdue to a stone, distension of the gall bladder rarly occurs; In obstruction from other causes, distension of the gall bladder is common .

58

ManagementIt is essential to determine whether the jaundice is due to liverdisease, disease within the duct, such as sclerosing cholangitis, orobstruction of the biliary tree. Ultrasound scanning, liver functiontests, liver biopsy and MRI or ERCP will delineate the nature of the obstruction.The patient may be ill. Pus may be present within the biliarytree, and liver abscesses may develop. Full supportive measures are required with1- rehydration,2- correction of clotting abnormalities3- treatment with appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics.Once the patient has been resuscitated, relief of the obstruction is essential. ERCP with a sphincterotomy, removal of the stones using a Dormia basket or the placement of a stent if stone removal is not possible. If this technique fails, percutaneous transhepatic Cholangiography can be performed to provide drainage and subsequent percutaneous choledochoscopy. Surgery, in the form of choledochotomy, is now rarely used .

Choledochotomy The aim of this surgery is to drain the common bile duct and remove the stones by a longitudinal incision in the duct. When the duct clear of stones, a T-tube is inserted and the duct closed ; the bile is allowed to drain externally. When the bile hasbecome clear and the patient has recovered, a cholangiogram isperformed, usually 7–10 days following operation. If residualstones are found, the T-tube is left in place for 6 weeks so thatthe track is ‘mature’.

Stricture of the bile ductCauses of benign biliary strictureCongenital■ Biliary atresiaBile duct injury at surgery■ Cholecystectomy■ Choledochotomy■ Gastrectomy■ Hepatic resection■ TransplantationInflammatory■ Stones■ Cholangitis■ Parasitic■ Pancreatitis■ Sclerosing cholangitis■ RadiotherapyTraumaIdiopathic

Radiological investigation of biliary strictures■ Ultrasonography■ Cholangiography via T-tube, if present■ ERCP■ MRCP■ PTC ■ CT

PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITISPrimary sclerosing cholangitis is an idiopathic fibrosing inflammatory condition of the biliary tree that affects both intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts. It is of unknown origin, but association with elevated markers such as smooth muscle antibodies and anti-nuclear f actor suggests an immunological cause. The majority of patients are 30 - 60 years of age. Strongly association with inflammatory bowel disease, especiallyulcerative colitis.

Common symptoms include right upper quadrant discomfort,

jaundice, pruritus, fever, fatigue and weight loss.Investigation

reveals a cholestatic pattern in liver function tests with elevation

of serum alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Imaging studies

such as MRCP or ERCP may demonstrate stricturing and beading of the bile ducts

A liver biopsy is helpful in confirming the diagnosis

and may help to guide therapy by excluding cirrhosis.

The important differential diagnoses are secondary sclerosing cholangitis and cholangiocarcinoma.

.

Management with antibiotics, vitamin K, cholestyramine,

steroids and immunosuppressants such as azathioprine isgenerally unsuccessful. Endoscopic stenting of dominant strictures in extrahepatic disease,

operative resection may be worthwhile. For patients with

cirrhosis, liver transplantation is the best option

PARASITIC INFESTATION OF THE BILIARY

TRACTBiliary ascariasis

The round worm, Ascaris lumbricoides, commonly infests the

intestine of inhabitants of Asia, Africa and Central America. It may enter the biliary tree through the ampulla of Vater and cause biliary pain

Complications include strictures, suppurative

cholangitis, liver abscesses and empyema of the gall bladder. In the uncomplicated case, anti-spasmodics can be given to relax the sphincter of Oddi, and the worm will return to the small intestine to be dealt with by antihelminthic drugs. Operation may be necessary to remove the worm or deal with complications.

Worms can be extracted via the ampulla of Vater by ERCP

Hydatid disease

A large hydatid cyst may obstruct the hepatic ducts. Sometimes,a cyst will rupture into the biliary tree and its contents cause obstructive jaundice or cholangitis, requiring appropriate surgeryTUMOURS OF THE BILE DUCT

Benign tumours of the bile ductThese are uncommon and need to be distinguished from other

benign conditions such as choledocholithiasis, sclerosing cholangitis,Caroli’s disease and choledochal cysts.

Benign neoplasms causing biliary obstruction may be classified

as follows:

• papilloma and adenoma;

• multiple biliary papillomatosis;

• granular cell myoblastoma;

• neural tumours;

• leiomyoma;

• endocrine tumours.

Malignant tumours of the bile duct(cholangiocarcinoma)

Carcinoma may arise at any point in the biliary tree, from the commonbile duct to the small intrahepatic ducts .

Incidence

This is a rare malignancy accounting for 1–2% of new cancers .

with two-thirds of patients being older than 65 years.

Histologically, the tumour is usually an adenocarcinoma

(cholangiocarcinoma).

Associations

Patients with a history of ulcerative colitis, hepatolithiasis, choledochal

cyst or sclerosing cholangitis . In addition liver fluke infestations in the Far East . Opisthorchis viverrini infestation is important in Thailand and Malaysia. These parasites induce DNA changes and mutations through production of carcinogens and free radicals, which stimulate cellular proliferation in the intrahepatic bile ducts and lead to invasive cancer .

Clinical features

Biliary tract cancers tend to be slow-growing tumours that invade

locally and metastasise to local lymph nodes. Distant metastases

to the peritoneal cavity, liver and lung do occur. Jaundice is the

most common presenting feature. Abdominal pain, early satiety

and weight loss are also commonly seen. On examination, jaundice

is evident, cachexia and a palpable gall bladder is present if the obstruction is in the distal common bile duct (Courvoisier’s sign).

Investigations

1-Biochemical investigations will confirm the presence of obstructive jaundice (elevated bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase andgamma-glutamyl transferase).

2-The tumour marker CA19-9 may also be elevated.

3- Non-invasive studies such as ultrasound and CT

scanning define the level of biliary obstruction, the extent of disease and the presence of metastases .

For proximal tumours, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography is the most useful modality, it allows percutaneous

biliary drainage, and samples can be obtained for cytology

to confirm the diagnosis.

For distal tumours, an ERCP is preferred as an endobiliary stent can be placed across the obstructing lesion.

Again, cytology or biopsies can be taken for diagnosis

Treatment

The treatment depends on the site and extent of disease. Mostpatients are inoperable, surgical resection, , resection may involve partial hepatectomy and reconstruction of the biliary tree. Distal common duct tumours may require a pancreaticoduodenectomy. with 20% of patients surviving 5 years post resection. Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy has a limited role.

Carcinoma of the gall bladder

Incidence

This is a rare disease ,The highest incidence is in Chileans,

American Indians and in parts of northern India, In western practice,gall bladder cancer accounts for less than 1% of new cancer diagnoses.The patients are usually older, in their sixties or seventies.

The aetiology is unclear, but there may be an association with -----1-preexisting gallstone disease.

2- Calcification of the gall bladder is associated with cancer . 3-Infection may promote the development of cancer as the risk of carcinoma in typhoid carriers is significantly increased.

Clinical features

Patients may be asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. If symptomsare present, they are usually indistinguishable from benign

gall bladder disease such as biliary colic or cholecystitis, Jaundice and anorexia are late features.

A palpable mass is a late sign.

Pathology

The majority of cases are adenocarcinoma (90%). Grossly, carcinomas are difficult to differentiate from chronic cholecystitis

Investigation

Laboratory findings may be consistent with biliary obstruction ornon-specific findings such as anaemia, leucocytosis, mild elevation

in transaminases and increased erythrocyte sedimentation

rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP). The level of serum

CA19-9 is elevated in 80% of patients. The diagnosis is made on

ultrasonography and CT scan,

with a percutaneous biopsy confirming the histological diagnosis.

In selected patients, laparoscopy is useful in staging the disease,

as it can detect peritoneal or liver metastases .

Treatment and prognosis

Occasionally, the diagnosis is made by histological examination of

a gall bladder removed for ‘benign’ gallstone disease. For earlystage

disease confined to the mucosa or muscle of the gall

bladder, no further treatment is indicated. However, for transmural

disease, a radical en bloc resection of the gall bladder fossa

and surrounding liver along with the regional lymph nodes should

be performed. a 5-year survival is 5%.

.