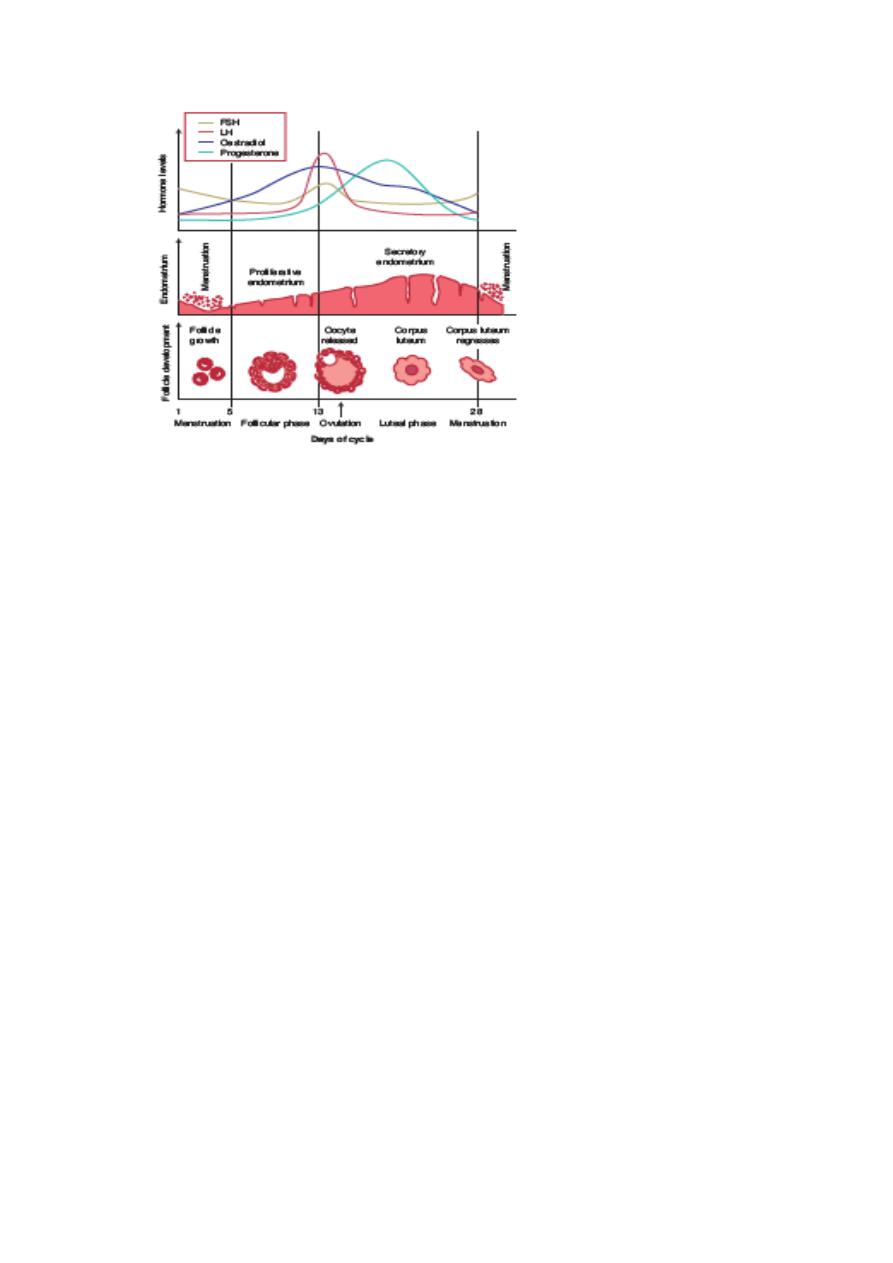

Normal menstrual cycle

Introduction

The external manifestation of a normal menstrual

cycle is the presence of regular

vaginal bleeding. This

occurs as a result of the shedding of the endometrial lining

following failure of fertilization of the oocyte or failure of implantation. The cycle

depends on changes occurring within the ovaries and fluctuation in ovarian hormone

levels, that are themselves controlled by the pituitary and hypothalamus, the

hypothalamo

–pituitary–ovarian axis (HPO)

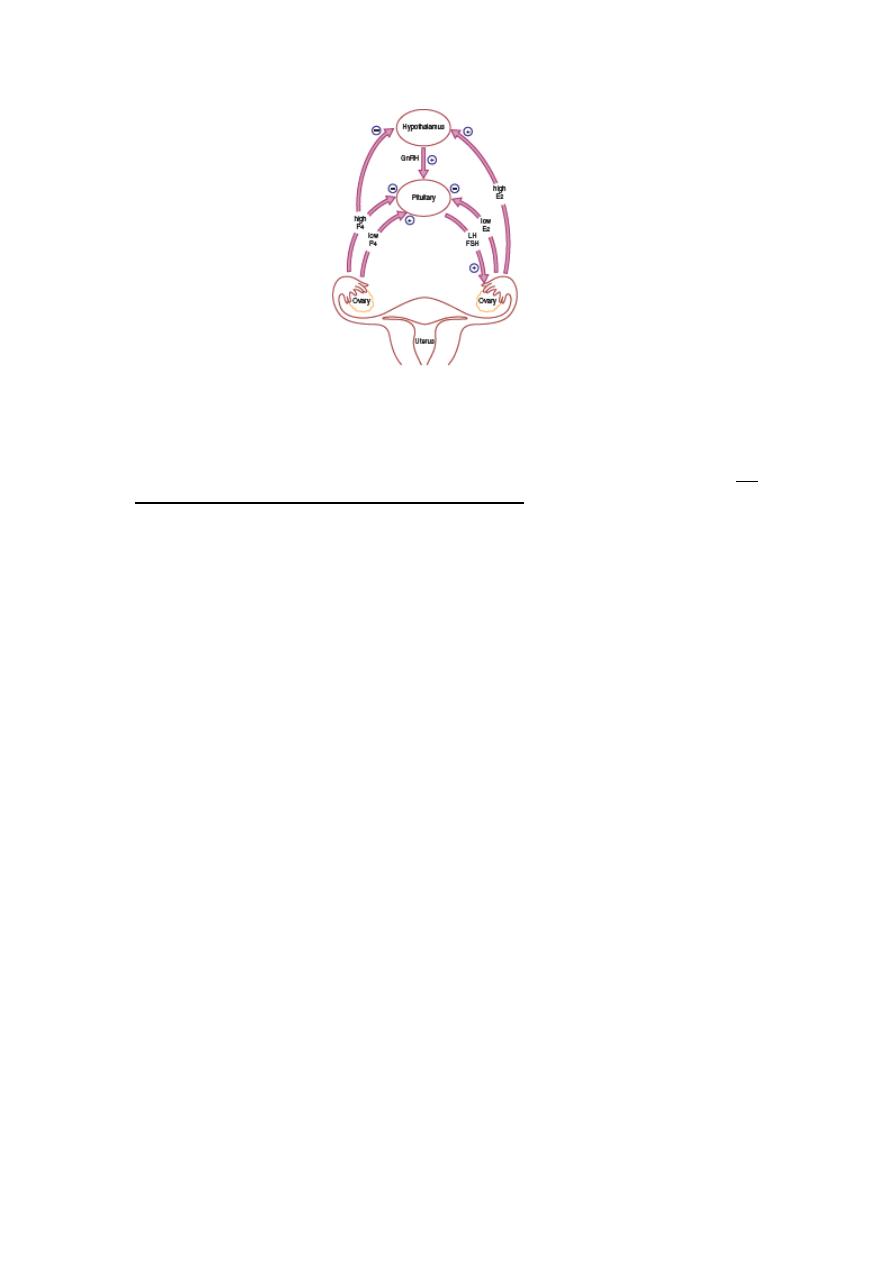

Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus in the forebrain secretes the peptide hormone gonadotrophin-

releasing hormone (GnRH), which in turn controls pituitary hormone secretion.

GnRH must be released in a pulsatile fashion to stimulate pituitary secretion of

luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). If GnRH is given

in a constant high dose, it desensitizes the GnRH receptor and reduces LH and FSH

release.

Pituitary gland

GnRH stimulation of the basophil cells in the anterior pituitary gland causes synthesis

and release of the gonadotrophic hormones, FSH and LH. This process is modulated

by the ovarian sex steroid hormones oestrogen and progesterone. Low levels of

oestrogen have an inhibitory effect on LH production (negative feedback), whereas

high levels of oestrogen will increase LH production (positive feedback). The high

levels of circulating oestrogen in the late follicular phase of the ovary act via the

positive feedback mechanism to generate a periovulatory LH surge from the pituitary.

Unlike oestrogen, low levels of progesterone have a positive feedback effect on

pituitary LH and FSH secretion (as seen immediately prior to ovulation) and

contribute to the FSH surge. High levels of progesterone, as seen in the luteal phase,

inhibit pituitary LH and FSH production. Positive feedback effects of progesterone

occur via increasing sensitivity to GnRH in the pituitary. Negative feedback effects

are generated through both decreased GnRH production from the hypothalamus and

decreased sensitivity to GnRH in the pituitary. It is known that progesterone can only

have these effects on gonadotropic hormone release after priming by oestrogen.

Inhibin and activin are peptide hormones produced by granulosa cells in the ovaries,

with opposing effects on gonadotrophin production. Inhibin inhibits pituitary FSH

secretion, whereas activin stimulates it.

Ovary

Ovaries with developing oocytes are present in the female fetus from an early stage of

development. By the end of the second trimester

in utero, the number of oocytes has

reached a maximum and they arrest at the first prophase step in meiotic division. No

new oocytes are formed during the female lifetime.

With the onset of menarche, the primordial follicles containing oocytes will activate

and grow in a cyclical fashion, causing ovulation and subsequent menstruation in the

event of non-fertilization. In the course of a normal menstrual cycle, the ovary will go

through three phases:

1

Follicular phase

2

Ovulation

3

Luteal phase.

Follicular phase

The initial stages of follicular development are independent of hormone stimulation.

FSH levels rise in the first days of the menstrual cycle, when oestrogen, progesterone

and inhibin levels are low. This stimulates a cohort of small antral follicles on the

ovaries to grow.

Within the follicles, there are two cell types which are involved in the processing of

steroids, including oestrogen and progesterone. These are the theca and the

granulosa cells, which respond to LH and FSH stimulation, respectively. LH

stimulates production of androgens from cholesterol within theca cells. These

androgens are converted into oestrogens by the process of aromatization in granulosa

cells, under the influence of FSH.

Both FSH and LH are required to generate a normal cycle with adequate amounts of

oestrogen.

As the follicles grow and oestrogen secretion increases, there is negative feedback on

the pituitary

to decrease FSH secretion. This assists in the selection of one follicle to

continue in its development towards ovulation

– the dominant follicle. In the ovary,

the follicle which has the most efficient aromatase

activity and highest concentration

of FSH-induced LH receptors will be the most likely to survive as FSH levels drop,

while smaller follicles will undergo atresia.

The dominant follicle will go on producing oestrogen and also inhibin, which

enhances androgen synthesis under LH control.

There are other autocrine and paracrine mediators playing a role in the follicular

phase of the menstrual cycle. These include inhibin and activin.

Insulin-like growth factors (IGF-I, IGF-II) act as paracrine regulators. Circulating

levels do not change during the menstrual cycle, but follicular fluid levels increase

towards ovulation, with the highest level found in the dominant follicle.

In the follicular phase, IGF-I is produced by theca cells under the action of LH.

Within the theca, IGF-I augments LH-induced steroidogenesis.

In granulosa cells, IGF-I augments the stimulatory effects of FSH on mitosis,

aromatase activity and inhibin production. In the preovulatory follicle,

IGF-I enhances LH-induced progesterone production from granulosa cells. Following

ovulation, IGF-II is produced from luteinized granulosa cells, and acts in an autocrine

manner to augment LH-induced proliferation of granulosa cells.

Kisspeptins are proteins which have more recently been found to play a role in

regulation of the HPO axis, via the mediation of the metabolic hormone leptin

’s effect

on the hypothalamus. Leptin is thought to be key in the relationship between energy

production, weight and reproductive health. Mutations in the kisspeptin receptor, are

associated with delayed or absent puberty,

Ovulation

By the end of the follicular phase, which lasts an average of 14 days, the dominant

follicle has grown to approximately 20 mm in diameter. As the follicle matures, FSH

induces LH receptors on the granulose cells and prepare for the signal for ovulation.

Production of oestrogen increases until they reach the necessary threshold to exert a

positive feedback effort on the hypothalamus and pituitary to cause the LH surge.

This occurs over 24

–36 hours, during which time the LH-induced luteinization of

granulosa cells in the dominant follicle causes progesterone to be produced, adding

further to the positive feedback for LH secretion and causing a small periovulatory

rise in FSH. Androgens, synthesized in the theca cells, also rise around the time of

ovulation .

The LH surge is one of the best predictors of imminent ovulation,

The LH surge has another function in stimulating the resumption of meiosis in the

oocyte just prior to its release.

The physical ovulation of the oocyte occurs after breakdown of the follicular wall

occurs under the influence of LH, FSH and progesterone controlled

proteolytic enzymes, such as plasminogen activators and prostaglandins. There

appears to be an inflammatory-type response within the follicle wall which may assist

in extrusion of the oocyte by stimulating smooth muscle activity. So inhibition of

prostaglandin production may result in failure of ovulation. Thus, women wishing to

become pregnant should be advised to avoid taking prostaglandin synthetase

inhibitors, such as aspirin and ibuprofen, which may inhibit oocyte release.

Luteal phase

After the release of the oocyte, the remaining granulose and theca cells on the ovary

form the corpus luteum.

The granulosa cells have a vacuolated appearance with accumulated yellow pigment,

hence the name corpus luteum (

‘yellow body’). The corpus luteum undergoes

extensive vascularization in order to supply granulosa cells with a rich blood supply

for continued steroidogenesis.

Ongoing pituitary LH secretion and granulosa cell activity ensures a supply of

progesterone which stabilizes the endometrium in preparation for pregnancy.

Progesterone levels are at their highest in the cycle during the luteal phase. This also

has the effect of suppressing FSH and LH secretion to a level that will not produce

further follicular growth in the ovary during that cycle.

The luteal phase lasts 14 days in most women, without great variation. In the absence

of beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (

HCG) being produced from an implanting

embryo, the corpus luteum will regress in a process known as luteolysis. The mature

corpus luteum is less sensitive to LH, produces less progesterone, and will gradually

disappear from the ovary. The withdrawal of progesterone has the effect on the uterus

of causing shedding of the endometrium and thus menstruation. Reduction in levels of

progesterone, oestrogen and inhibin feeding back to the pituitary cause increased

secretion of gonadotrophic hormones, particularly FSH. New preantral follicles begin

to be stimulated and the cycle begins anew.

Endometrium

The hormone changes effected by the HPO axis during the menstrual cycle will occur

whether the uterus is present or not. However, the specific secondary

changes in the

uterine endometrium give the most

obvious external sign of regular cycles.

Menstruation

The endometrium is under the influence of sex steroids that circulate in females of

reproductive age. Sequential exposure to oestrogen and progesterone will result in

cellular proliferation and differentiation, in preparation for the implantation of an

embryo in the event of pregnancy, followed by regular bleeding in response to

progesterone withdrawal if the corpus luteum regresses. During the ovarian follicular

phase, the endometrium undergoes proliferation (the

‘proliferative phase’); during

the ovarian luteal phase, it has its

‘secretory phase’. Decidualization, the formation

of a specialized glandular endometrium, is an irreversible process and apoptosis

occurs if there is no embryo implantation. Menstruation (day 1) is the shedding of

the

‘dead’ endometrium and ceases as the endometrium regenerates (which normally

happens by day 5

–6 of the cycle).

The endometrium is composed of two layers, the uppermost of which is shed during

menstruation. A fall in circulating levels of oestrogen and progesterone approximately

14 days after ovulation leads to loss of tissue fluid, vasoconstriction of spiral

arterioles and distal ischaemia. This results in tissue breakdown, and loss of the upper

layer along with bleeding from fragments of the remaining arterioles is seen as

menstrual bleeding. Enhanced fibrinolysis reduces clotting.

Vaginal bleeding will cease after 5

–10 days as arterioles vasoconstrict and the

endometrium begins to regenerate. Haemostasis in the uterine endometrium is

different from haemostasis elsewhere in the body as it does not involve the processes

of clot formation and fibrosis.

Prostaglandin F2

, endothelin-1 and plateletmactivating factor (PAF) are

vasoconstrictors which are produced within the endometrium and are thought likely to

be involved in vessel constriction, both initiating and controlling menstruation. They

may be balanced by the effect of vasodilator agents, such as prostaglandin E2,

prostacyclin (PGI) and nitric oxide (NO), which are also produced by the

endometrium. Progesterone withdrawal increases endometrial prostaglandin (PG)

synthesis and decreases PG metabolism. The COX-2 enzyme and chemokines are

involved in PG synthesis and this is likely to be the target of non-steroidal anti-

inflammatory agents used for the treatment of heavy and painful periods.

Endometrial repair involves both glandular and stromal regeneration and

angiogenesis to reconstitute the endometrial vasculature. VEGF and fibroblast growth

factor (FGF) are found within the endometrium and both are powerful angiogenic

agents. Other growth factors, such as transforming growth factors (TGFs), epidermal

growth factor (EGF) and IGFs, and the interleukins may also be important.

The proliferative phase

Menstruation will normally cease after 5

–7 days, once endometrial repair is complete.

After this time, the endometrium enters the proliferative phase, when glandular and

stromal growth occur. The epithelium lining the endometrial glands changes from a

single layer of columnar cells to a pseudostratified epithelium with frequent mitoses.

The stroma is infiltrated by cells derived from the bone marrow . Endometrial

thickness increases rapidly, from 0.5 mm at menstruation to 3.5

–5 mm at the end of

the proliferative phase.

The secretory phase

After ovulation (generally around day 14), there is a period of endometrial glandular

secretory activity. Following the progesterone surge, the oestrogen induced cellular

proliferation is inhibited and the endometrial thickness does not increase any further.

However, the endometrial glands will become more tortuous, spiral arteries will grow,

and fluid is secreted into glandular cells and into the uterine lumen. Later in the

secretory phase, progesterone induces the formation of a temporary layer, known as

the decidua, in the endometrial stroma. Histologically, this is seen as occurring

around blood vessels. Stromal cells show increased mitotic activity, nuclear

enlargement and generation of a basement membrane

Recent research into infertility has identified apical membrane projections of the

endometrial epithelial cells known as pinopodes, which appear after day 21

–22 and

appear to be a progesterone-dependent stage in making the endometrium receptive for

embryo implantation .

Immediately prior to menstruation, three distinct layers of endometrium can be

seen. The basalis is the lower 25 per cent of the endometrium, which will

remain

throughout menstruation and shows few

changes during the menstrual cycle. The mid-

portion is the stratum spongiosum with oedematous stroma and exhausted glands.

The superficial portion (upper 25 per cent) is the stratum compactum with

prominent decidualized stromal cells. On the withdrawal of both oestrogen and

progesterone, the decidua will collapse, with vasoconstriction and relaxation of spiral

arteries and shedding of the outer layers of the endometriu

m