The musculature is involved directly in several important phases of complete denture treatment. Most obvious, of course, is the action of muscles as prime movers of the mandible and hence as the power for repeated occlusion of the teeth. In addition, they are active during mastication, deglutition, and speech. They exert a direct and indirect influence upon the peripheral extensions, shape, and thickness of denture bases, the positions of teeth both horizontally and vertically, and facial appearance.

Myology related to complete denture

Muscle:

is a soft tissue made up of a large number of fibers bound together by areolar connective tissue into bundles, or fasciculi. The bundles are surrounded by connective tissue sheaths and grouped together into still larger bundles. The whole muscle is enveloped by a connective tissue sheath, the epimysium.There are three types of muscles in the human body:

1-Skeletal muscles 2-Smooth muscles 3-cardiac muscles.The muscles that are intimately involved in complete denture service are defined as skeletal (from their site of origin or attachment), striated (from their morphology), and voluntary (controlled by the will).

In the majority of skeletal muscles, the origins and insertions are in bone.

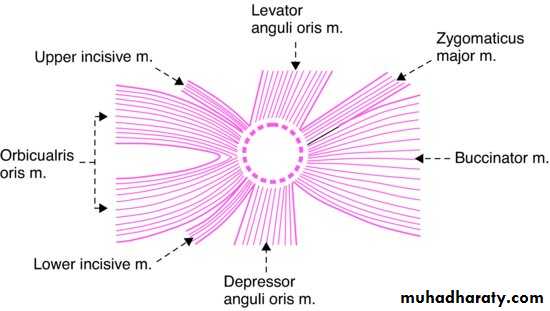

However, many of the skeletal muscles involved in complete denture construction have a bony origin but insert into an aponeurosis, a raphe, or another muscle.The orbicularis oris has no bony origin or insertions, and its primary function is to close the oral orifice (sphincter).

When the origins and insertions of a muscle are in bone, there is a limitation to the positions and action of the muscles. When an attachment is in an aponeurosis, a raphe, or a muscle, a more flexible relation exists.

muscles of mastication have their origins and insertions in bone, with one exception. (the uppermost fibers of the upper head of the external pterygoid insert into the mandibular articular capsule and thus indirectly into the anterior border of the articular disc.)

This knowledge is utilized in making jaw relation records, particularly centric relation or centric position. Centric relation is a bone-to-bone relation controlled by the attached musculature, the tissue-lined bonny fossae, the ligaments and the neuromyons.

The muscles of facial expression, the muscles of the tongue, the suprahyoid muscles, the muscles of the soft palate, and the pharyngeal muscles do not have both origins and insertions in bone. These are the muscles primarily involved with the extent of the denture borders, the contour of the denture bases and the positions of the teeth.

Muscles of expression

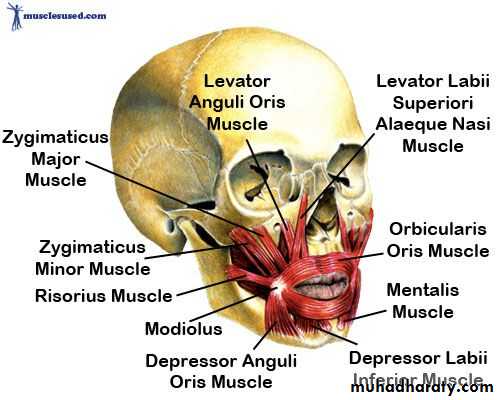

The zygomaticus, quadratus labii superioris, levator anguli oris, mentalis, quadratus labii inferioris, depressor anguli oris,risorius, platysma, upper incisal, lower incisal, orbicularis oris and the buccinator are responsible for the various expressions seen in the lower half of the face. The actions of these muscles often reflect the mental state, the personality, and the well-being of an individual.

The muscles of facial expression do not insert into bone and need support from the teeth for proper function. If the muscles of facial expression are not properly supported, either by the natural teeth or by the artificial substitutes, none of the facial expressions appears normal. When the artificial teeth are placed in positions that do not support the muscles of facial expression in the manner of the natural teeth or if for other reasons the muscles loss tonus, the facial expression changes. Another problem is the tendency to cheek biting when the denture teeth are placed in the positions formerly occupied by the natural posterior teeth. With patient training and a return of the tonus, the problem is relieved.

Furthermore, these muscles depend on a proper vertical dimension of the face as determined by the occlusion of the teeth in order that they may be neither stretched beyond their ideal length nor permitted to sag.

The origins of several muscles of facial expression are near enough to the denture-bearing areas that their actions must be considered as definitely influencing the denture borders. Their influence is in proportion to the contour and quantity of residual ridge present in a vertical direction. The higher the residual ridge, the less influence these muscle attachments will exert.

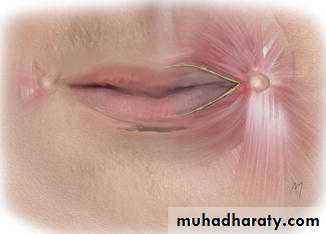

In an area situated laterally and slightly above the corner of the mouth is a concentration of the many fibers of this muscle group. This concentration is known as the muscular node or modiolus and continues downward as a tendinous strip of varying lengths. The modiolus represents the origin, insertion or decussation of many fibers of various muscles of facial expression. The labial flanges of the maxillary denture frequently need to be reduced lateromedially in the area of the modiolus. When the bundle of muscles is stretched during mouth opening, the vestibular space between the bundle in the cheek and the slopes of the residual alveolar ridges are restricted. To reduce the bulk of the flange to accommodate this muscular action helps to prevent dislodgment of the denture when the mouth is opened. At times, if the tendinous strips extend downward extensively, the mandibular denture base should be reduced lateromedially.

The mentalis muscle elevates the skin of the chin and turns the lower lip outwards. The contraction of this muscle is capable of dislodging a mandibular denture, particularly when the residual ridge in its anterior region is nonexistent.

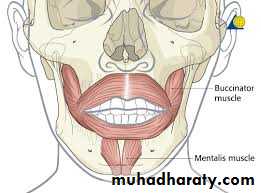

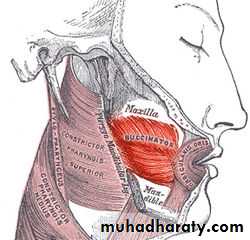

The buccinator muscle forms the mobile and adaptive substance of the cheeks. It arises from the outer surface of the maxilla and the mandible opposite the sockets of the first molar teeth. In addition to , and in between these bony attachments, it originates from the pterygomandibular raphe or ligament. The ligament serves as a bond of union between the buccinator and the superior constrictor of the pharynx. Most of the fibers insert into the mucous membrane of the cheek in and around the tendinous node and tendinous line. The other fibers terminate in the skin of the upper and lower lips near the commissure. It is in the lower jaw that the muscle becomes a part of the denture-bearing area. Not only does it become part of the denture-bearing area but where extreme or total loss of residual ridge exists, the buccinator and the mylohyoid have been demonstrated to cover the bony support from the first molar area to the retromolar pad.

Fortunately, the action of the fibers of the buccinator does not dislodge the denture. The action is parallel to the plane of occlusion.

The fibers parallel to the occlusal plane are at right angles to the fibers of the masseter muscle. When the masseter is activated, it pushes the buccinator medially against the denture border in the area of retromolar pad. This is a dislodging force and the denture base should be contoured to accommodate this action; this contour in the denture base is termed the masseter groove.

The action of the buccinator muscles pulls the corners of the mouth laterally and posteriorly. Its main function is to keep the cheeks taut.Another very important function of this muscle is its part in the kinetic chain of swallowing.

The orbicularis oris muscle is the sphincter muscle of the mouth. The upper lip is supported by the six maxillary anterior teeth, not the denture border. When the teeth are in occlusion the superior border of the lower lip is supported by the incisal third of the maxillary anterior teeth; if this were not so, the lower lip would be caught between the anterior teeth during occlusal contacting.

The insertion of the muscles of facial expression distal to the corners of the mouth at the modiolus and the position and action of the orbicularis oris have a definite influence in impression making. These muscles can be relaxed with the jaws open, and this relaxation is desirable when introducing the impression tray or impression material. The patient should be trained to open the jaws and relax the lips and cheeks to avoid interference from a pair of tense lips. When the lips are tense, a stretching action often results in lacerations at the corners of the mouth and/or distorted impression material.

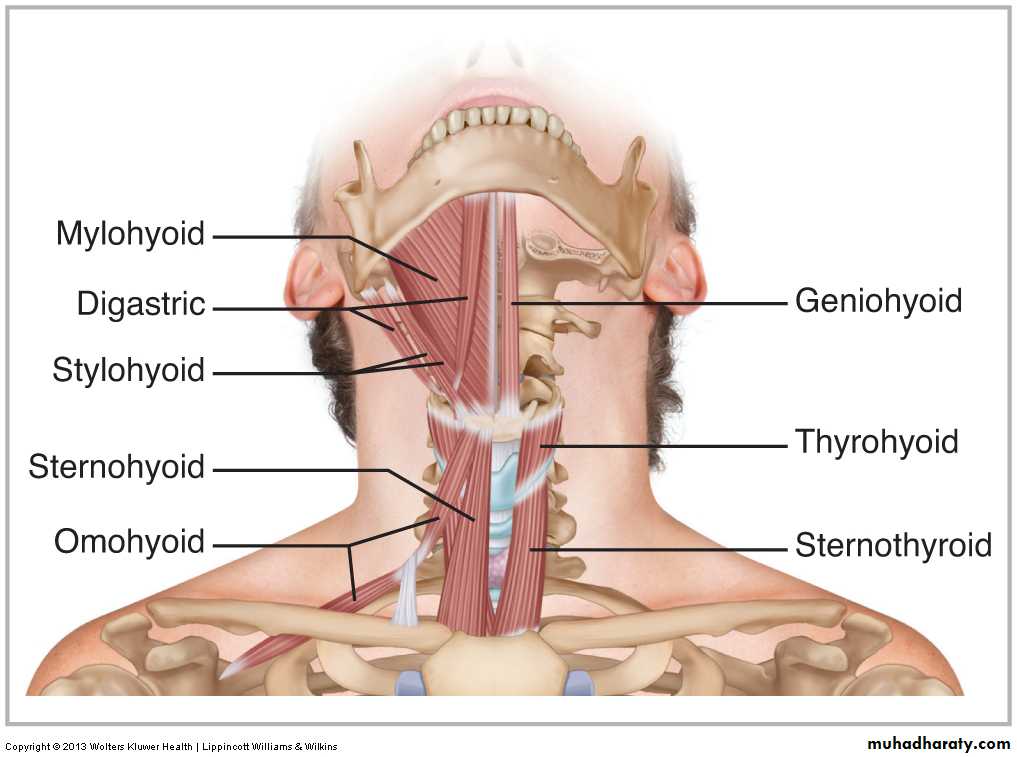

Suprahyoid muscles

The digastric, stylohyoid, mylohyoid, and geniohyoid comprise this group of muscles. The mylohyoid and geniohyoid influence the borders of the mandibular dentures. If the denture flange is extended below and under the mylohyoid line, it will impinge upon the mylohyoid muscle and will affect its action adversely, or the action of the muscle will unseat the denture. Because the fibers are directed downward, the denture flange can extend below the mylohyoid line but not under. This places the inferior border of the denture in a compatible position with the tongue.

The geniohyoid muscle presents no problem in complete denture construction until there is extensive loss of the residual ridge.

Infrahyoid muscles

The origin and insertion of this group of muscles, which consists of the

sternohyoid, omohyoid, sternothyroid, and thyrohyoid, have no particular significance in complete denture prosthodontics insofar as having any influence on the denture borders.

The action of these muscles is important to the prosthodontist, for they are a part of the kinetic chain of the mandibular movement. Their action is to fix the hyoid bone, as it were, to the trunk. It is from this fixed position that the suprahyoid muscles can act upon the mandible.

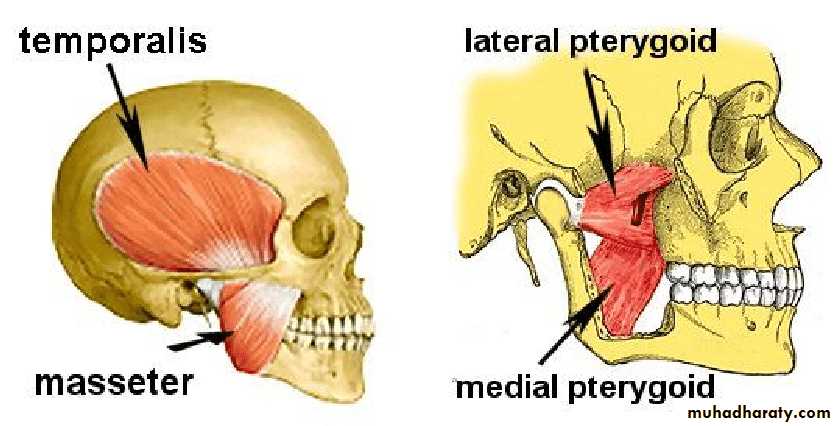

Muscles of mastication

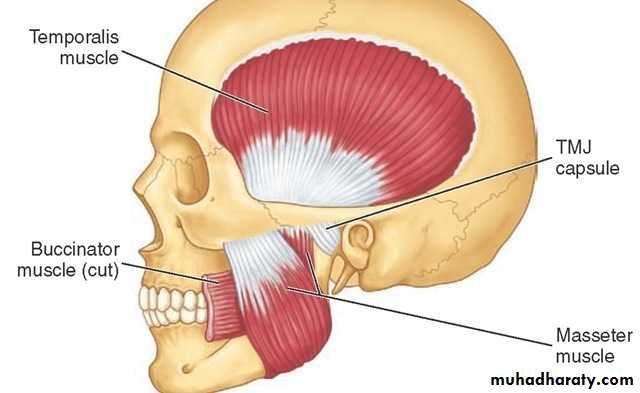

The muscles that have been designated as the muscles of mastication-the masseter, the temporalis, the internal pterygoid and the external pterygoid-have their origins from the bones of the skull and are attached to the mandible. These muscles are involved not only in the masticatory movements of the mandible, but also in the nonmasticatory. In complete denture prosthodontics the nonmasticatory movements and the contacting of teeth during these movements are probably of more concern than the masticatory movements.

The group of four muscles designated as the muscles of mastication are not the only muscles involved in the masticatory processes; neither is mastication their only function. Other groups of musculature(as in the tongue, cheek, and hyoid) are described as accessory muscles of mastication and incidentally as muscles of deglutition and speech.

Only one of these directly influences the contour of the denture base. The contracture of the masseter forces the buccinator muscle in a medial direction in the area of the retromolar pad.

Tongue

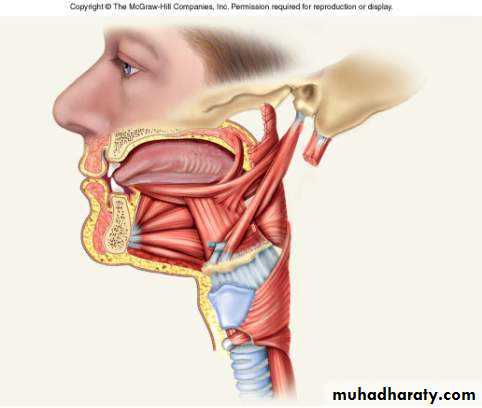

The tongue is a muscular organ, attached with its base and the central part of its body to the floor of the mouth. The denture flanges must be contoured to allow the tongue its normal range of functional movements.

The muscular activity of the tongue is controlled by two groups of muscles, the intrinsic and extrinsic. The intrinsic muscles, being wholly inside the tongue, can only produce changes of shape in the tongue. The extrinsic group (genioglossus, styloglossus, hyoglossus and palatoglossus) take origin from parts outside the tongue and can move the tongue as well as alter its shape.

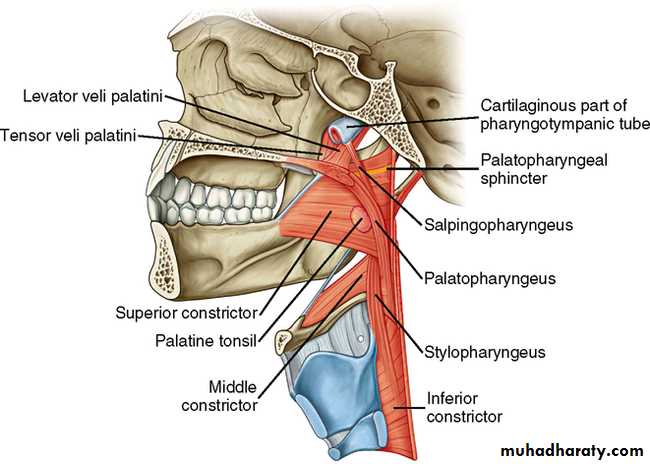

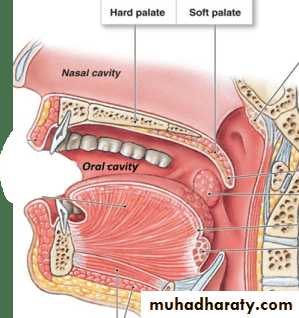

Muscles of the soft palate

The tensor palati, levator palati, azygos uvulae, palatoglossus, and palatopharyngeus are the muscles of the soft palate, which is a movable curtain extending downward and backward into the pharynx. During deglutition it is raised and helps to shut off the nasal part of the pharynx from the portion below.

The posterior extension of the maxillary denture base rests in the soft palate. This area is the palatine aponeurosis. This tendinous sheet lies in the anterior two-thirds of the soft palate and is attached to the crest on the lower surface of the bony palate near its posterior end.

Near the bony palate the muscle fibers are very scanty, and the aponeurosis is thick and strong at the junction; the anterior part of the soft palate is therefore more horizontal and less movable than the posterior part. The character of the aponeurosis and the overlying mucosa, the activity of the palatine muscles, and the contour of the soft palate determine the extent and the contour of the posterior palatal seal. The seal should be in the soft palate not over the palatine bone.

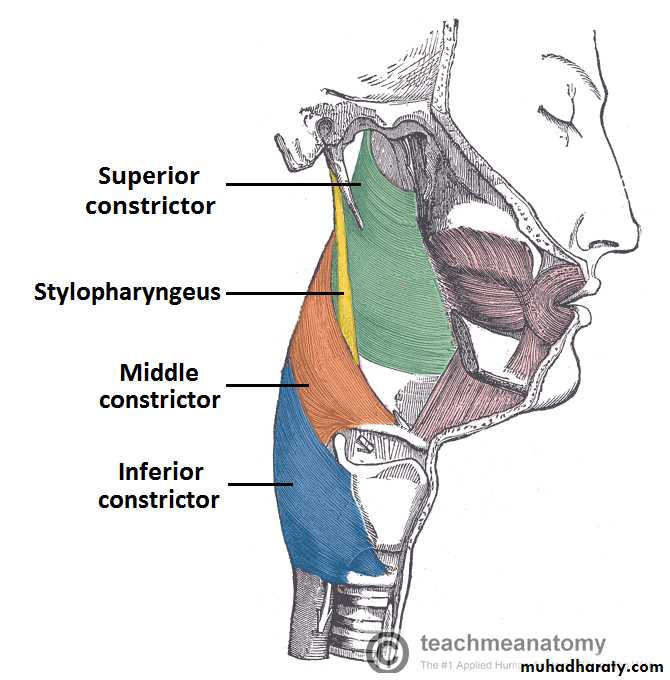

Pharyngeal muscles

The superior constrictor is the pharyngeal muscle of most interest in complete denture construction.The action of this muscular band exerts pressure against the distal extremity of the mandibular denture. Overextension in this area is very painful to the patient, as the denture will perforate the tissue and cause a sore throat.

In that the muscles which move the mandible are under control of the will ,i.e., the central nervous system, under physiologic conditions the muscles can be directed to move. At the first consultation appointment, patients can be given a training exercise that will prepare them for the time of jaw relation records. This exercise is accomplished at home, in a relaxed atmosphere, three times daily facing a large mirror. The mandible is relaxed and with the jaws separated slightly more than rest position, not a wide separation, the chin is brought forward (protruded) until it stops. From this position, the jaw is carried backward (retruded) until the condyles are felt to stop in the fossae. This exercise is continued during the construction phase, but make certain that patients are fully aware of when the condyles stop in the fossae. At the time of recording the jaw relations, patient is first rehearsed, and then with the recording records in place, is directed to protrude, retrude to feel the condyle stop, and then close on the back teeth (recording media) until the anterior teeth touch.

With exercise, muscle alters its shape and size. This property of muscle provides a method for improving the shape and size of the tongues that are abnormal in size, position, and/or function.

If a muscle contracts slowly or if contraction is rapid, the efficiency to do work is decreased. Maximum efficiency is developed when the velocity of contraction is about 30 per cent of maximum. If a muscle is in a highly contractile state, it may contract more strongly than normal. When a muscle contracts under physiologic conditions, the antagonist muscle relaxes. However, under abnormal conditions the antagonist muscle can become activated, and the result will be a change in the contracting muscle. If a muscle is already shortened before it is stimulated to contract, the force of contraction is less than normal. If it is stretched before contraction, the force will also be less than normal. These and other physiologic muscle actions are important in recording the jaw relations and also in educating patients in denture use.

Muscle tissue has two physical properties that must be considered, extensibility and elasticity. When a load is placed on a muscle, the muscle elongates, and within limits, the greater the load, the greater the stretch. When the load is released, the muscle shortens almost to its original length. Because a contracted muscle has greater elasticity than a resting muscle, an overloaded muscle may elongate when it contracts. These two properties limit or lessen the danger of rupturing when excessive strain is placed on a muscle. The property of elongation should be considered when jaw relations are recorded under manual pressure.

Gradation of contraction refers to the different degrees of force that can be exerted by a muscle. A muscle contraction is so well graded by the nervous control that almost any degree of contraction can be called forth from a muscle. The gradation of contraction of almost any muscle of the body is almost lacking in limits. The phenomenon of muscle control is one of the reasons that reaction of the denture-supporting tissues in one individual varies from that of another; the degree of contraction is not the same.

Another interesting phenomenon of muscle is its power to undergo physical contracture. For e.g., If a patient receives complete upper and lower denture with an excessive interocclusal distance, the fibers of the elevator muscles actually shorten and reestablish new muscle lengths approximately equal to the maximum length of the lever system itself, thus reestablishing optimum force of contraction by a muscle. Constant overstretching of the depressor muscles, makes their normal contraction impossible and will cause these muscles to lose power, to weaken.

When muscles are at rest, a certain amount of tonus usually remains. This residual degree of contraction in skeletal muscle is called muscle tone. Most skeletal muscle tone is caused by nerve impulses from the spinal cord. The nerve impulses are controlled by impulses from the brain and impulses that originate in the muscle spindles. The blocking of muscle spindle impulses causes loss of muscle tone, and the muscle becomes almost flaccid. The afferent impulses are necessary for the generating of tonus.

Prolonged and strong contraction of a muscle leads to fatigue. If a muscle becomes fatigued to an extreme extent, it is likely to become continually contracted, remaining contracted for many minutes even without an action potential as a stimulus. When the fatigue is over, the muscle gradually relaxes. If an individual’s mandible is protruded and allowed to remain until fatigue occurs, the antagonist action to the retractor and elevator muscles will be weakened. It would be possible to retrude and elevate the mandible to the centric position against very little or no opposing action from the external pterygoid.

Muscles of expression in the lower half of the face

Modiolus

Mentalis muscle

Buccinator muscle

When the masseter is activated, it pushes the buccinator medially against the denture border in the area of retromolar pad.

Suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles

Muscles of mastication

Muscle

Origin

Insertion

Main Action

Temporalis

Floor of temporal fossa and deep surface of temporal fascia.

Tip and medial surface of coronoid process and anterior border of ramus of mandible.

Elevates mandible, closing jaws; posterior fibers retrude mandible after protrusion.

Masseter

Inferior border and medial surface of zygomatic arch.Lateral surface of ramus of mandible and coronoid process

Elevates and protrudes mandible, thus closing jaws; deep fibers retrude it.

Lateral pterygoid

Superior head: infratemporal surface and infratemporal crest of greater wing of sphenoid bone.

Inferior head: lateral surface of lateral pterygoid plate.

Neck of mandible, articular disc, and capsule of temporomandibular joint

Acting bilaterally, protrude mandible and depress chin; acting unilaterally alternately, they produce side-to-side movements of mandible.

Medial pterygoid

Deep head: medial surface of lateral pterygoid plate and pyramidal process of palatine bone.

Superficial head: tuberosity of maxilla.

Medial surface of ramus of mandible, inferior to mandibular foramen.

Helps elevate mandible, closing jaws; acting bilaterally protrude mandible; acting unilaterally, protrudes side of jaw; acting alternately, they produce a grinding motion.

Pharyngeal muscles

TongueSoft palate

Muscles of the soft palateMM