Association and causation

Dr. Sijal Fadhil Farhood AL-joborae

F.I.C.M.S community (Baghdad)

M.Sc. Community (Nahrain)

M.B.Ch.B (Babylon University)

introduction

In previous lectures we studied the designs of

epidemiologic studies that are used to determine whether

an association exists between an exposure and a disease

,We then addressed different types of risk measurement

that are used to quantitatively express an excess in risk.

If we determine that an exposure is associated with a

disease.

The next question is whether the observed association

reflects a causal relationship????

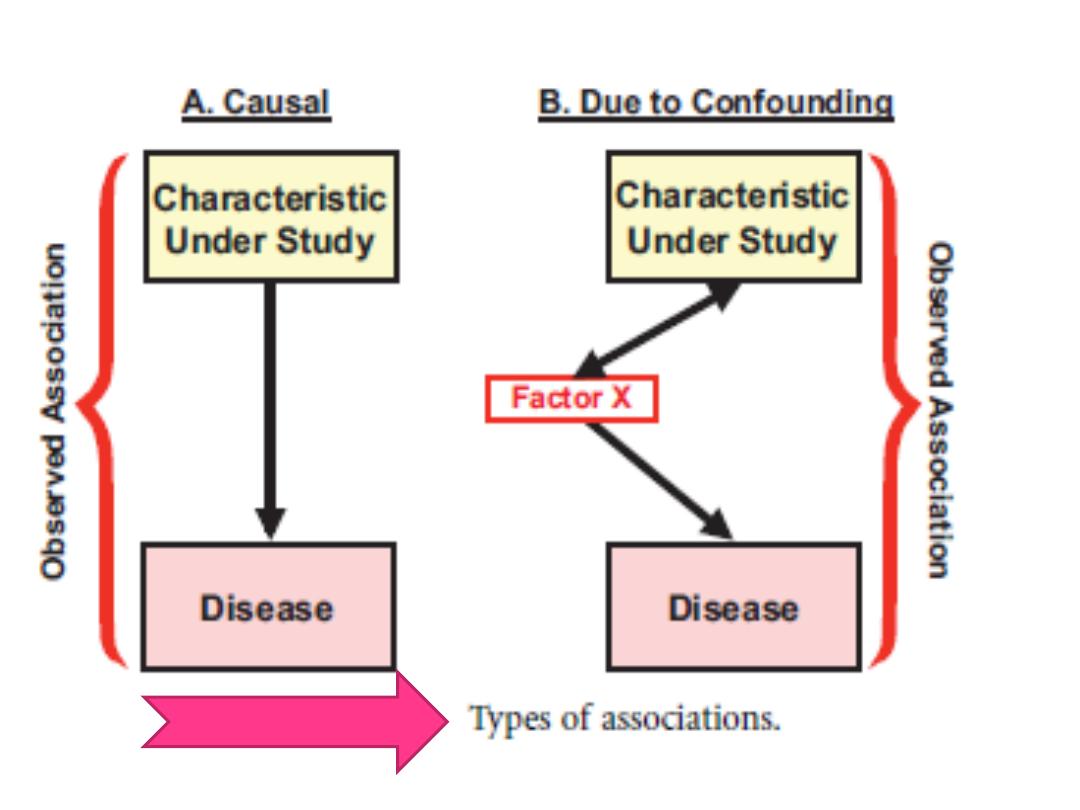

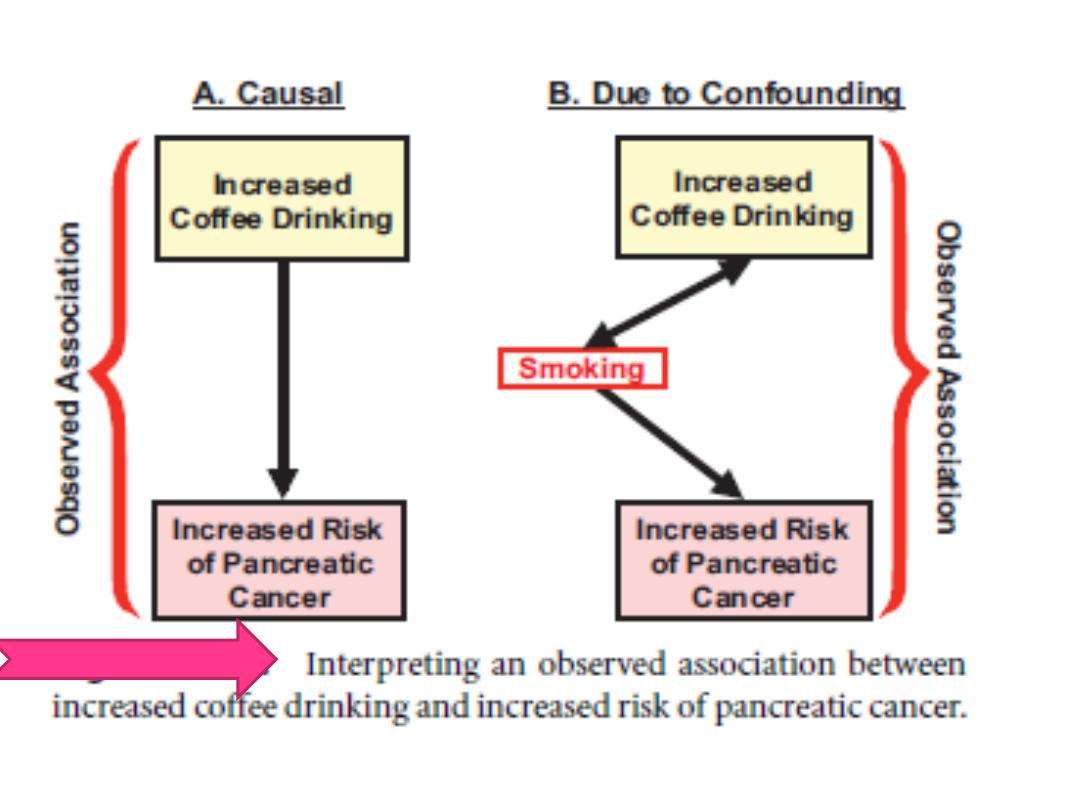

TYPES OF ASSOCIATIONS

Real or Spurious Associations

Interpreting real association:

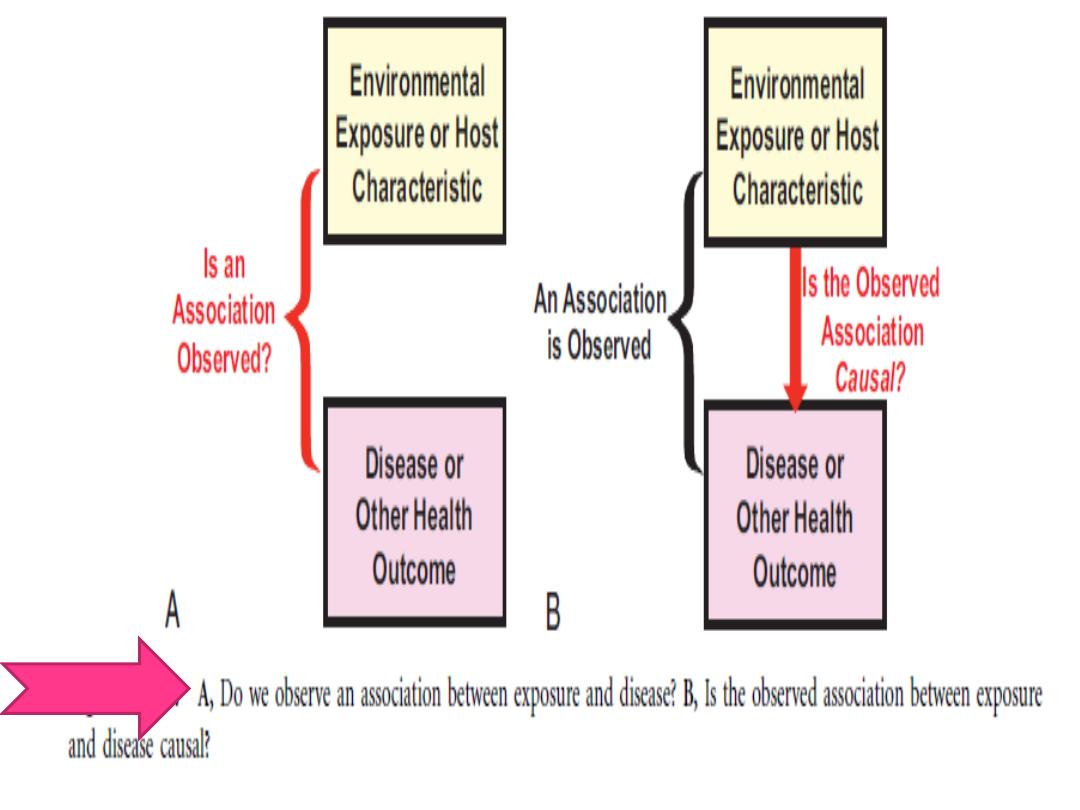

A :shows a causal association: we observe an association of

exposure and disease and the exposure induces development of

the disease.

B:shows the same observed association of exposure

and disease, but they are associated only because they are both

linked to a third factor, designated here as factor X. This

association is a result of confounding and is non-causal.

TYPES OF CAUSAL

RELATIONSHIPS

•

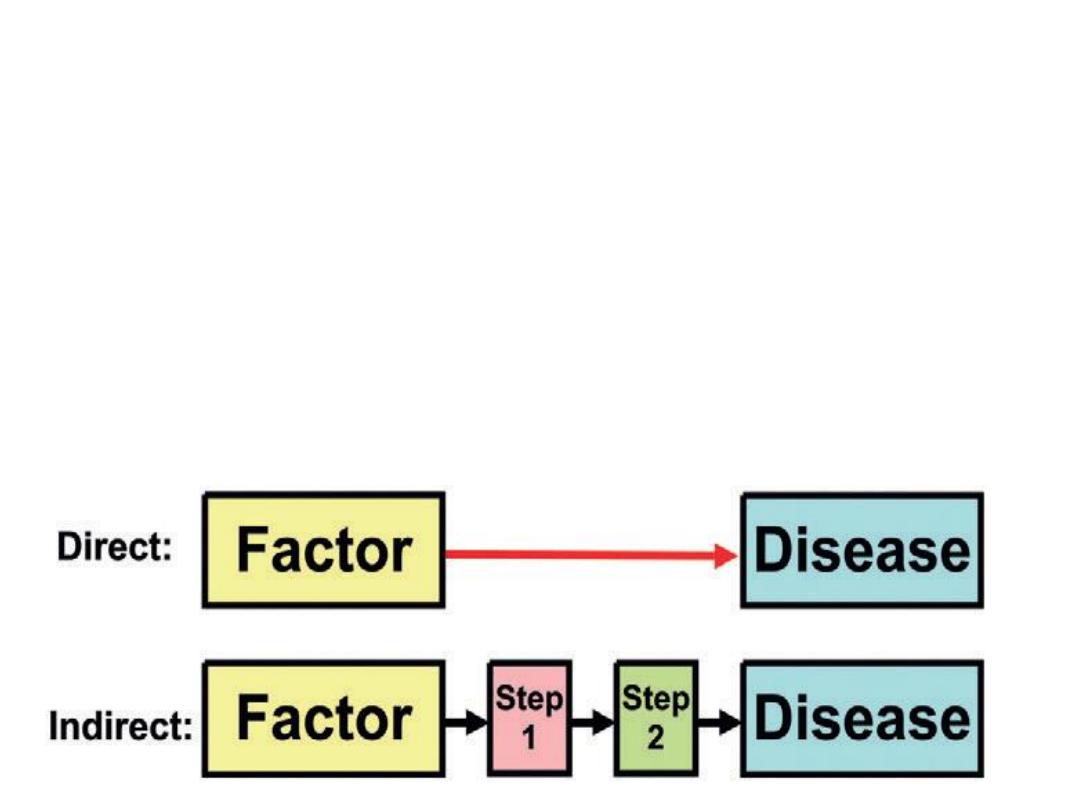

A causal pathway can be either

direct

or

indirect

In

direct

causation, a factor directly causes a disease without any

intermediate step. In

indirect

causation, a factor that causes a

disease, but only through an intermediate step or steps. In

human

biology, intermediate steps are virtually always present in any

causal process.

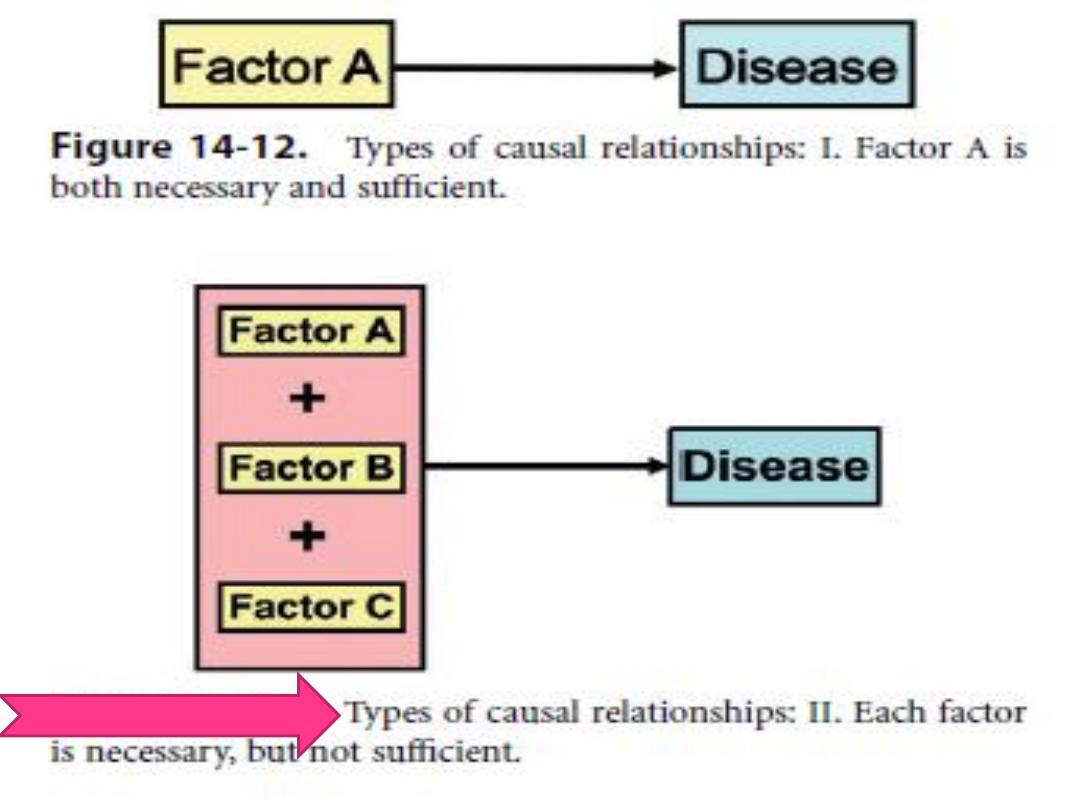

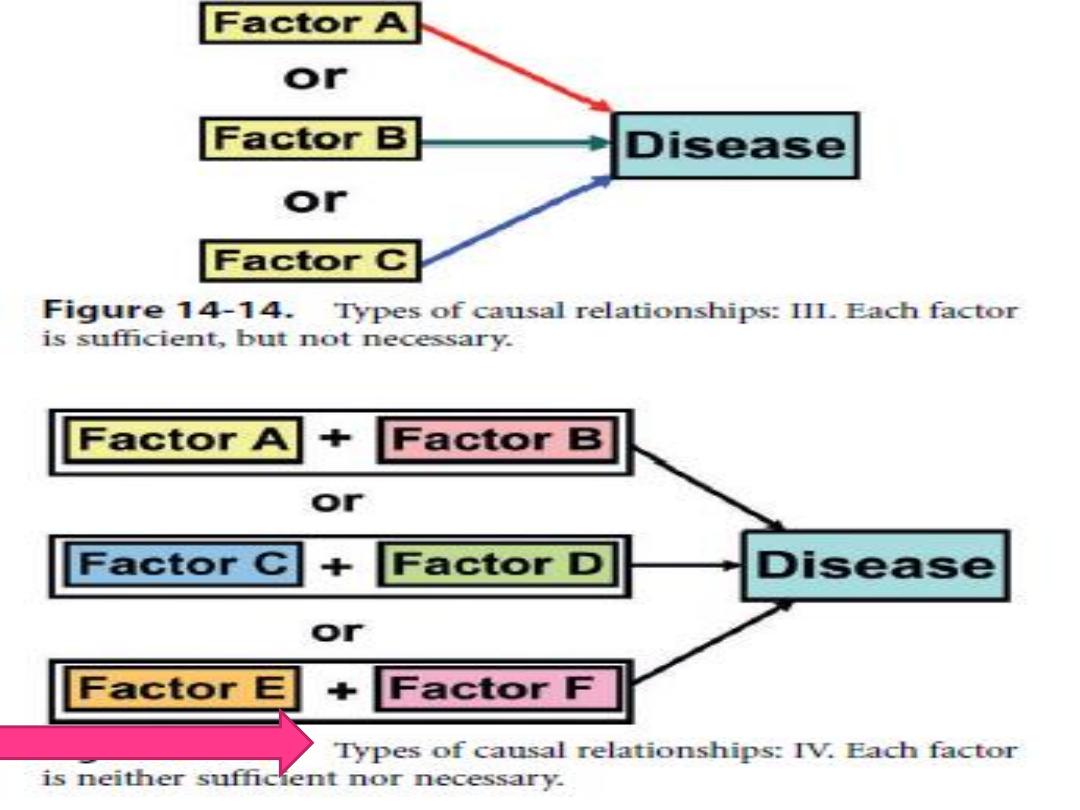

If a relationship is causal; four types of causal relationships are

possible:

(1) necessary and sufficient.

(2) necessary, but not sufficient.

(3) sufficient, but not necessary.

(4) neither sufficient nor necessary.

Necessary and Sufficient

A factor is both necessary and sufficient for

producing the

disease. Without that factor, the disease never

develops(the factor is necessary), and in the

presence of that factor, the disease always develops

(the factor is sufficient)

For example, in most infectious diseases, a number of

people are exposed, some of whom will manifest the

disease and others who

will not. Members of households of a person with

tuberculosis do not uniformly acquire the disease from

the index case. If the exposure dose is assumed to be the

same, there are likely differences in immune status,

genetic susceptibility, or other characteristics

that determine who develops the disease and who does

not. A one-to-one relationship of exposure to disease,

which is a consequence of a necessary and sufficient

relationship, rarely if ever occurs.

Necessary, But Not Sufficient

Each factor is necessary, but not, in itself, sufficient

to cause the disease Thus, multiple factors are

required, often in a specific temporal sequence

carcinogenesis is considered to be a multistage

process involving both initiation and promotion.

For cancer to result, a promoter must act after an

initiator has acted. Action of an initiator or a

promoter alone will not produce a cancer.

Sufficient, But Not Necessary

In this model, the factor alone can produce the disease, but

so can other factors that are acting alone ,Thus, either

radiation exposure or benzene exposure can each produce

leukemia

without the presence of the other. Even in this situation,

however, cancer does not develop in everyone who has

experienced radiation or benzene exposure, so although

both factors are not needed, other cofactors probably are.

Thus, the criterion of

sufficient

is rarely met by a single

factor.

Neither Sufficient Nor Necessary

In the fourth model, a factor, by itself, is neither

sufficient nor necessary to produce disease ,This is a

more complex model, which probably most

accurately represents the causal relationships that

operate in most chronic diseases.

•

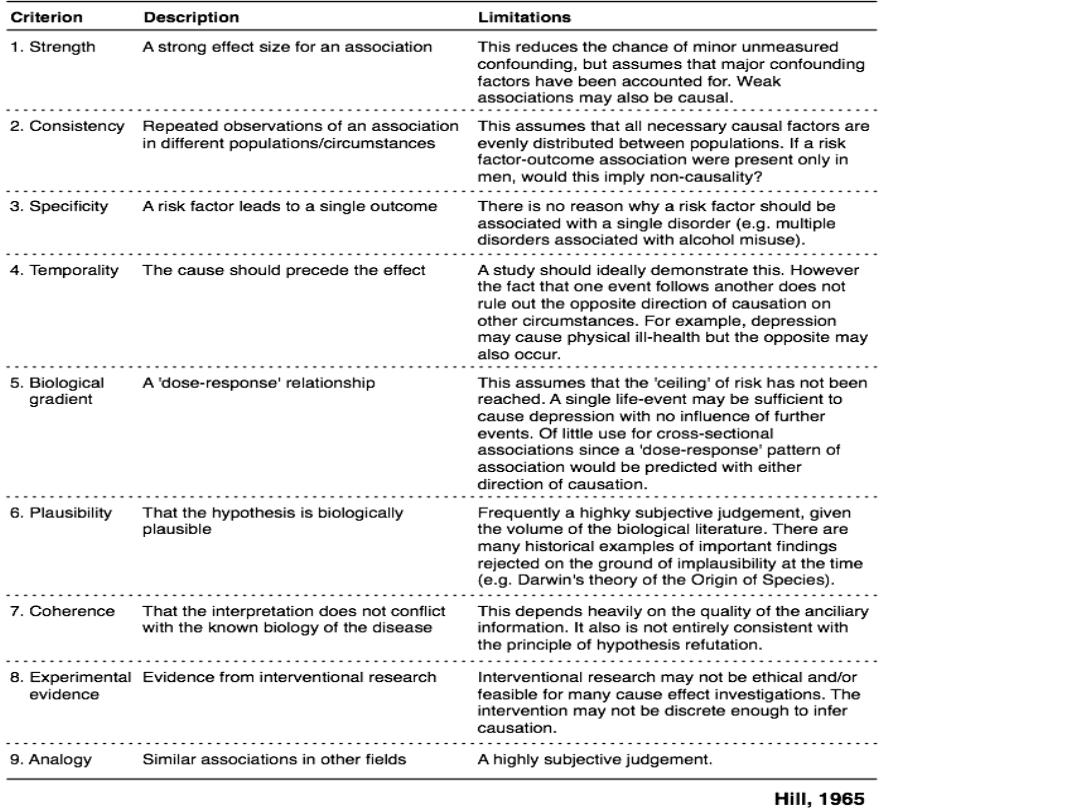

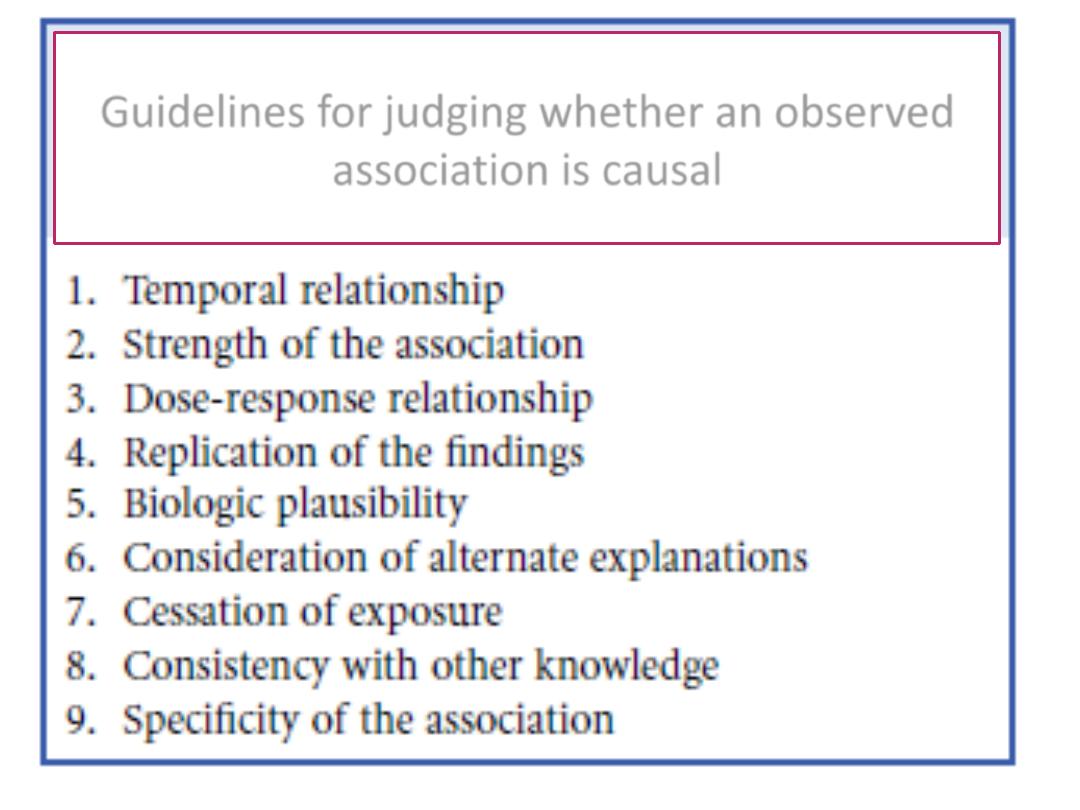

The Bradford Hill criteria ((Hill's criteria))

for causation, are a group of guidelines

that can be useful for providing evidence

of a causal relationship between a putative

cause and an effect, established by

the

(1897–1991) in 1965.

Guidelines for judging whether an observed

association is causal

1.

Temporal Relationship.

It is clear

that if a factor is believed to be the

cause of a disease, exposure to the

factor must have occurred before the

disease developed.

2-

Strength of the Association:

The strength of

the association is measured by the relative risk (or

odds ratio). The stronger the association, the more

likely it is that the relation is causal.

3-

Dose-Response Relationship:

As the dose of

exposure increases, the risk of disease also

increases.

4-Replication of the Findings.:

If the

relationship is causal, we would expect to

find it consistently in different studies and

in different populations.

5-Biologic Plausibility: Biologic plausibility

refers to coherence with the current body of

biologic knowledge.

6-Consideration of Alternate Explanations:

We have discussed the problem in interpreting an observed

association in regard to whether a relationship is causal or is the

result of confounding. In judging whether a reported association

is causal, the extent to which the investigators have taken

other possible explanations into account and the extent to

which they have ruled out such explanations are important

considerations.

7-Cessation of Exposure.:

If a factor is a cause of a

disease, we would expect the risk of the disease to decline when

exposure to the factor is reduced

8-Consistency with Other Knowledge:

If a

relationship is causal, we would expect the

findings to be consistent with other data.

9-Specificity of the Association:

An

association is specific when a certain exposure is

associated with only one disease; this is the

weakest of all the guidelines.

Question:

** All of the following are important criteria when

making causal inferences except:

a. Consistency with existing knowledge

b. Dose-response relationship

c. Consistency of association in several studies

d. Strength of association

e. Predictive value