Lec 8 Delayed puberty &infertility Dr. Nihad A. Aljeboori /Subspeciality diabetes &Endocrinoogy

Delayed puberty

Puberty is considered to be delayed if the onset of the physical features of sexual maturation

has not occurred by a chronological age that is 2.5 standard deviations (SD) above the

national average. In the UK, this is by the age of 14 in boys and 13 in girls. Genetic factors

have a major influence in determining the timing of the onset of puberty, such that the age of

menarche (the onset of menstruation) is often comparable within sibling and mother–

daughter pairs and within ethnic groups. However, because there is also a threshold for body

weight that acts as a trigger for normal puberty, the onset of puberty can be influenced by

other factors including nutritional status and chronic illness .

Clinical assessment

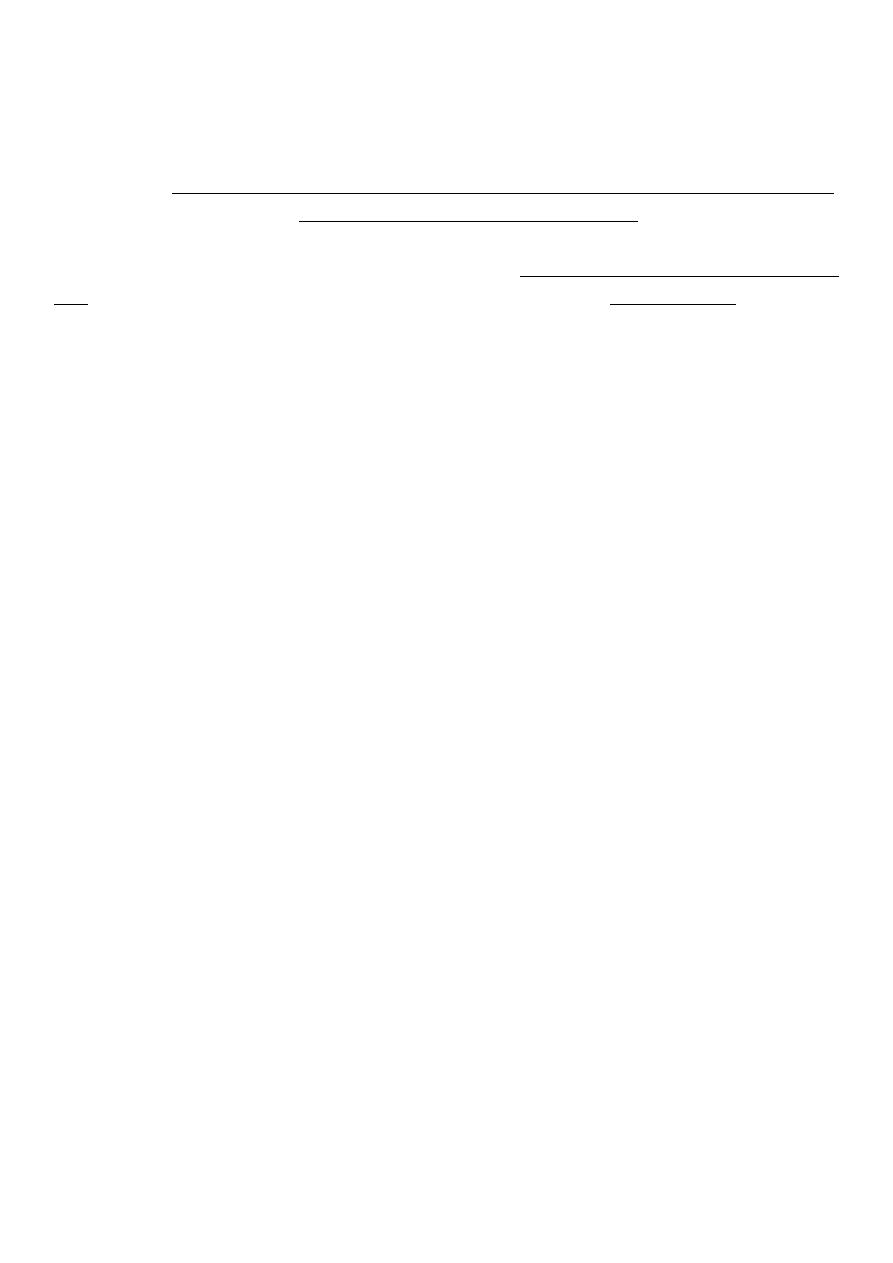

The differential diagnosis is shown in Box 18.20. The key issue is to determine whether the

delay in puberty is simply because the ‘clock is running slow’ (

constitutional delay of

puberty

) or because there is pathology in the hypothalamus/ pituitary (hypogonadotrophic

hypogonadism) or the gonads (hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism). A general history and

physical examination should be performed with particular reference to previous or current

medical disorders, social circumstances and family history. Body proportions, sense of smell

and pubertal stage should be carefully documented and, in boys, the presence or absence of

testes in the scrotum noted. Current weight and height may be plotted on centile charts, along

with parental heights. Previous growth measurements in childhood, which can usually be

obtained from health records, are extremely useful. Healthy growth usually follows a centile.

Usually, children with constitutional delay have always been small but have maintained a

normal growth velocity that is appropriate for bone age. Poor linear growth, with ‘crossing

of the centiles’, is more likely to be associated with acquired disease.

Lec 8 Delayed puberty &infertility Dr. Nihad A. Aljeboori /Subspeciality diabetes &Endocrinoogy

Constitutional delay of puberty

This is the most common cause of delayed puberty, but is a much more frequent explanation

for lack of pubertal development in boys than in girls. Affected children are healthy and have

usually been more than 2 SD below the mean height for their age throughout childhood.

There is often a history of delayed puberty in siblings or parents. Since sex steroids are

essential for fusion of the epiphyses, ‘bone age’ can be estimated by X-rays of epiphyses,

usually in the wrist and hand; in constitutional delay, bone age is lower than chronological

age. Constitutional delay of puberty should be considered as a normal variant, as puberty

will commence spontaneously. However, affected children can experience significant

psychological distress because of their lack of physical development, particularly when

compared with their peers.

Hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism

This may be due to structural, inflammatory or infiltrative disorders of the pituitary and/or

hypothalamus (see Box 18.54, p. 681). In such circumstances, other pituitary hormones, such

as growth hormone, are also likely to be deficient. ‘Functional’ gonadotrophin deficiency is

caused by a variety of factors, including low body weight, chronic systemic illness (as a

consequence of the disease itself or secondary malnutrition), endocrine disorders and

profound psychosocial stress. Isolated gonadotrophin deficiency is usually due to a genetic

abnormality that affects the synthesis of either GnRH or gonadotrophins. The most common

form is Kallmann’s syndrome, in which there is primary GnRH deficiency and, in most

affected individuals, agenesis or hypoplasia of the olfactory bulbs, resulting in anosmia or

hyposmia. If isolated gonadotrophin deficiency is left untreated, the epiphyses fail to fuse,

resulting in tall stature with disproportionately long arms and legs relative to trunk height

(eunuchoid habitus). Cryptorchidism (undescended testes) and gynaecomastia are commonly

observed in all forms of hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism.

Male hypogonadism

The clinical features of both hypo- and hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism include loss of

libido, lethargy with muscle weakness, and decreased frequency of shaving. Patients may

also present with gynaecomastia, infertility, delayed puberty, osteoporosis or anaemia of

chronic disease.

Mild hypogonadism may also occur in older men, particularly in the context of central

adiposity and the metabolic syndrome. Postulated mechanisms are complex and include

reduction in sex hormone binding globulin by insulin resistance and reduction in GnRH and

gonadotrophin secretion by cytokines or oestrogen released by adipose tissue. Testosterone

levels also fall gradually with age in men and this is associated with gonadotrophin levels

that are low or inappropriately within the ‘normal’ range. There is an increasing trend to

Lec 8 Delayed puberty &infertility Dr. Nihad A. Aljeboori /Subspeciality diabetes &Endocrinoogy

measure testosterone in older men, typically as part of an assessment of erectile dysfunction

and lack of libido.

Investigations

Male hypogonadism is confirmed by demonstrating a low fasting 0900-hr serum

testosterone level. The distinction between hypo- and hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism is

by measurement of random LH and FSH. Patients with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism

should be investigated as described for pituitary disease on page 680. Patients with

hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism should have the testes examined for cryptorchidism or

atrophy, and a karyotype should be performed (to identify Klinefelter’s syndrome).

Management

Testosterone replacement is clearly indicated in younger men with significant hypogonadism

to prevent osteoporosis and to restore muscle power and libido. Debate exists as to whether

replacement therapy is of benefit in mild hypogonadism associated with ageing and central

adiposity, particularly in the absence of structural pituitary/hypothalamic disease or other

pituitary hormone deficiency. In such instances, a therapeutic trial of testosterone therapy

may be considered if symptoms are present (e.g. low libido and erectile dysfunction), but the

benefits of therapy must be carefully weighed against the potential for harm. First-pass

hepatic metabolism of testosterone is highly efficient, so bioavailability of ingested

preparations is poor. Doses of systemic testosterone can be titrated against symptoms;

circulating testosterone levels may provide only a rough guide to dosage because they may

Lec 8 Delayed puberty &infertility Dr. Nihad A. Aljeboori /Subspeciality diabetes &Endocrinoogy

be highly variable . Testosterone therapy can aggravate prostatic carcinoma; prostate-specific

antigen (PSA) should be measured before commencing testosterone therapy in men older

than 50 years and monitored annually thereafter. Haemoglobin concentration should also be

monitored in older men, as androgen replacement can cause polycythaemia. Testosterone

replacement inhibits spermatogenesis; treatment for fertility is described below.

Infertility

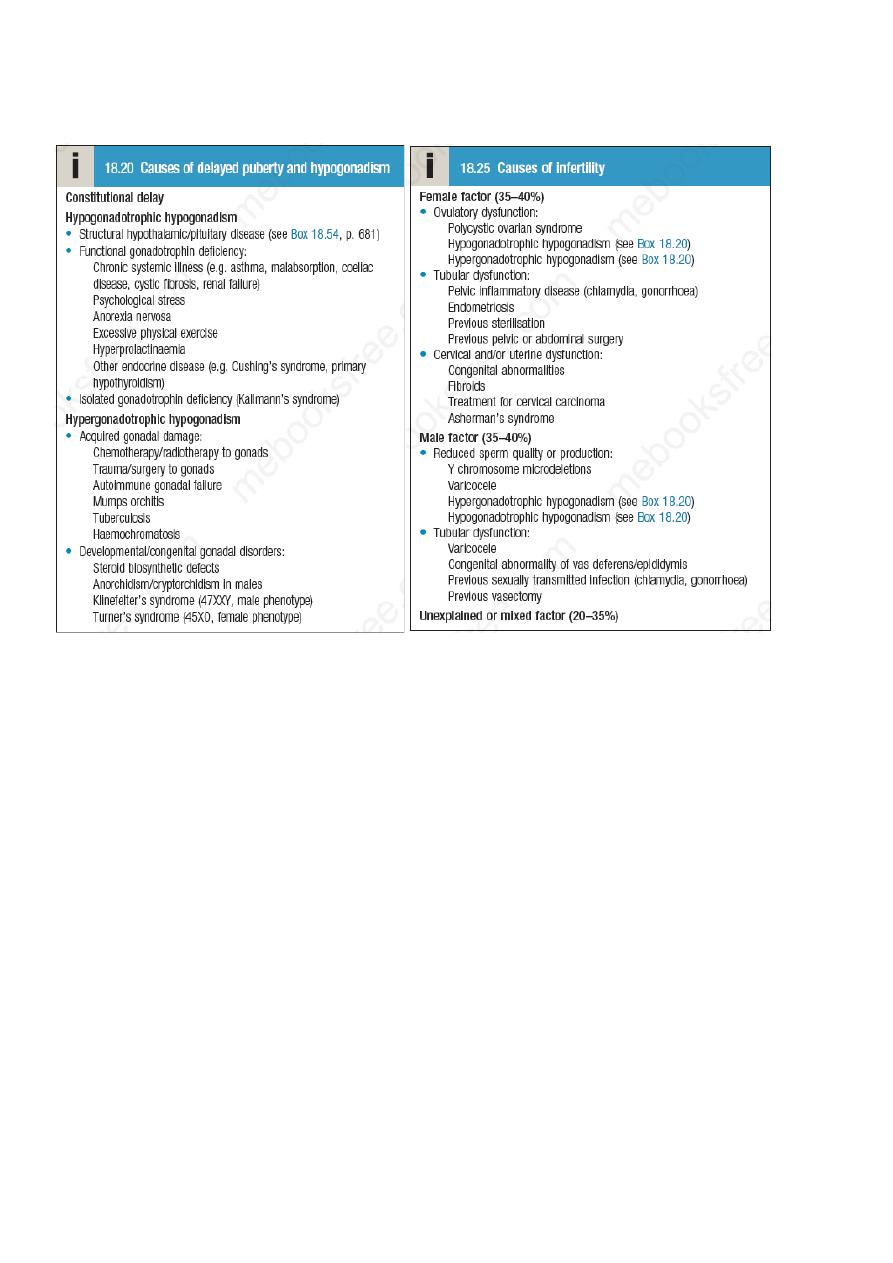

Infertility affects around 1 in 7 couples of reproductive age, often causing psychological

distress. The main causes are listed in Box 18.25. In women, it may result from anovulation

or abnormalities of the reproductive tract that prevent fertilisation or embryonic

implantation, often damaged Fallopian tubes from previous infection. In men, infertility may

result from impaired sperm quality (e.g. reduced motility) or reduced sperm number.

Azoospermia or oligospermia is usually idiopathic but may be a consequence of

hypogonadism. Microdeletions of the Y chromosome are increasingly recognised as a cause

of severely abnormal spermatogenesis. In many couples, more than one factor causing

subfertility is present, and in a large proportion no cause can be identified .

Clinical assessment

A history of previous pregnancies, relevant infections and surgery is important in both men

and women. A sexual history must be explored sensitively, as some couples have intercourse

infrequently or only when they consider the woman to be ovulating, and psychosexual

difficulties are common. Irregular and/or infrequent menstrual periods are an indicator of

anovulatory cycles in the woman, in which case causes such as PCOS should be considered.

In men, the testes should be examined to confirm that both are in the scrotum and to identify

any structural abnormality, such as small size, absent vas deferens or the presence of a

varicocele.

Investigations

Investigations should generally be performed after a couple has failed to conceive despite

unprotected intercourse for 12 months, unless there is an obvious abnormality like

amenorrhoea. Both partners need to be investigated. The male partner needs a semen

analysis to assess sperm count and quality. Home testing for ovulation (by commercial urine

dipstick kits, temperature measurement, or assessment of cervical mucus) is not

recommended, as the information is often counterbalanced by increased anxiety if

interpretation is inconclusive. In women with regular periods, ovulation can be confirmed by

an elevated serum progesterone concentration on day 21 of the menstrual cycle. Transvaginal

ultrasound can be used to assess uterine and ovarian anatomy. Tubal patency may be

examined at laparoscopy or by hysterosalpingography (HSG; a radio-opaque medium is

injected into the uterus and should normally outline the Fallopian tubes). In vitro

Lec 8 Delayed puberty &infertility Dr. Nihad A. Aljeboori /Subspeciality diabetes &Endocrinoogy

assessments of sperm survival in cervical mucus may be done in cases of unexplained

infertility but are rarely helpful.

Management

Couples should be advised to have regular sexual intercourse, ideally every 2–3 days

throughout the menstrual cycle. It is not uncommon for ‘spontaneous’ pregnancies to occur

in couples undergoing investigations for infertility or with identified causes of male or

female subfertility. In women with anovulatory cycles secondary to PCOS , clomifene,

which has partial anti-oestrogen action, blocks negative feedback of oestrogen on the

hypothalamus/pituitary, causing gonadotrophin secretion and thus ovulation. In women with

gonadotrophin deficiency or in whom anti-oestrogen therapy is unsuccessful, ovulation may

be induced by direct stimulation of the ovary by daily injection of FSH and an injection of

hCG to induce follicular rupture at the appropriate time. In hypothalamic disease, pulsatile

GnRH therapy with a portable infusion pump can be used to stimulate pituitary

gonadotrophin secretion (note that non-pulsatile administration of GnRH or its analogues

paradoxically suppresses LH and FSH secretion). Whatever method of ovulation induction is

employed, monitoring of response is essential to avoid multiple ovulation. For clomifene,

ultrasound monitoring is recommended for at least the first cycle. During gonadotrophin

therapy, closer monitoring of follicular growth by transvaginal ultrasonography and blood

oestradiol levels is mandatory. ‘Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome’ is characterised by

grossly enlarged ovaries and capillary leak with circulatory shock, pleural effusions and

ascites. Anovulatory women who fail to respond to ovulation induction or who have primary

ovarian failure may wish to consider using donated eggs or embryos, surrogacy and

adoption. Surgery to restore Fallopian tube patency can be effective but in vitro fertilisation

(IVF) is normally recommended. IVF is widely used for many causes of infertility and in

unexplained cases of prolonged (> 3 years) infertility. The success of IVF depends on age,

with low success rates in women over 40 years. Men with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism

who wish fertility are usually given injections of hCG several times a week (recombinant

FSH may also be required in men with hypogonadism of pre-pubertal origin); it may take up

to 2 years to achieve satisfactory sperm counts. Surgery is rarely an option in primary

testicular disease but removal of a varicocele can improve semen quality. Extraction of

sperm from the epididymis for IVF, and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI, when single

spermatozoa are injected into each oöcyte) are being used increasingly in men with

oligospermia or poor sperm quality who have primary testicular disease. Azoospermic men

may opt to use donated sperm but this may be in short supply