Female reproductive system

Normal menstrual cycle:

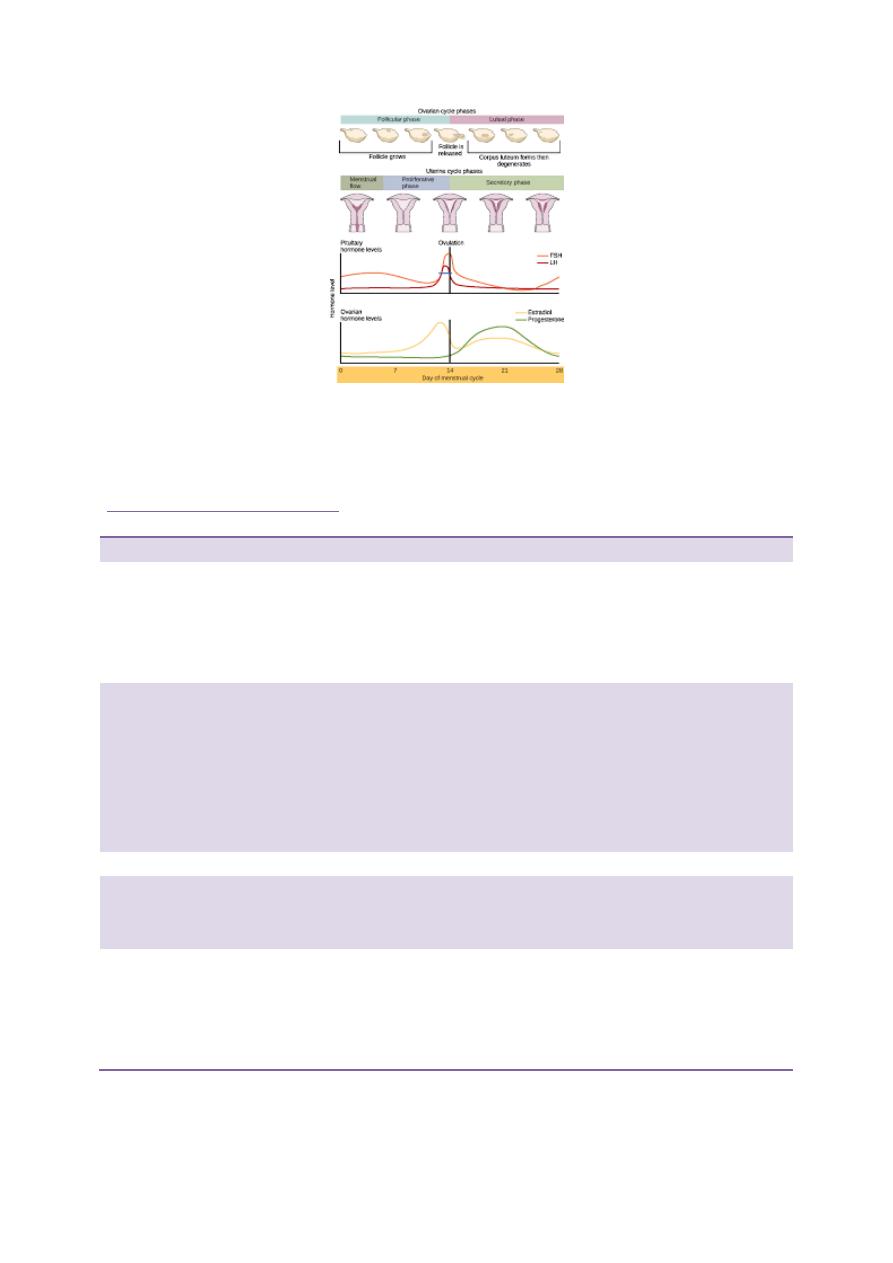

In the female, physiology varies during the normal menstrual cycle. FSH

stimulates growth and development of ovarian follicles during the first 14 days

after the menses. This leads to a gradual increase in oestradiol production from

granulosa cells, which initially suppresses FSH secretion (negative feedback)

but then, above a certain level, stimulates an increase in both the frequency and

amplitude of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulses, resulting in a

marked increase in LH secretion (positive feedback). The mid-cycle ‘surge’ of

LH induces ovulation. After release of the ovum, the follicle differentiates into a

corpus luteum, which secretes progesterone. Unless pregnancy occurs during

the cycle, the corpus luteum regresses and the fall in progesterone levels results

in menstrual bleeding. Circulating levels of oestrogen and progesterone in pre-

menopausal women are, therefore, critically dependent on the time of the cycle.

The most useful ‘test’ of ovarian function is a careful menstrual history: if

menses are regular, measurement of gonadotrophins and oestrogen is not

necessary. In addition, ovulation can be confirmed by measuring plasma

progesterone levels during the luteal phase (‘day 21 progesterone’)

Cessation of menstruation (the menopause) occurs at an average age of

approximately 50 years in developed countries. In the 5 years before, there is a

gradual increase in the number of anovulatory cycles and this is referred to as

the climacteric. Oestrogen and inhibin secretion falls and negative feedback

results in increased pituitary secretion of LH and FSH (both typically to levels

above 30 IU/L (3.3 μg/L)). See the following figure

Classification of reproductive system diseases

Primary

Secondary

Hormone excess

Polycystic ovarian

syndrome

Granulosa cell tumour

Leydig cell tumour

Teratoma

Pituitary

gonadotrophinoma

Hormone deficiency

Menopause

Hypogonadism

Turner’s syndrome

Klinefelter’s syndrome

Hypopituitarism

Kallmann’s syndrome

(isolated GnRH

deficiency)

Severe systemic illness,

including anorexia

nervosa

Hormone hypersensitivity Idiopathic hirsutism

Hormone resistance

Androgen resistance syndromes Complete (‘testicular feminisation’) Partial

(Reifenstein’s syndrome) 5α-reductase type 2 deficiency

Non-functioning tumours

Ovarian cysts

Carcinoma

Teratoma

Seminoma

Delayed puberty:

Puberty is considered to be delayed if the onset of the physical features of

sexual maturation has not occurred by a chronological age that is 2.5 standard

deviations (SD) above the national average. In the UK, this is by the age of 14

in boys and 13 in girls. Genetic factors have a major influence in determining

the timing of the onset of puberty, such that the age of menarche (the onset of

menstruation) is often comparable within sibling and mother–daughter pairs and

within ethnic groups. However, because there is also a threshold for body

weight that acts as a trigger for normal puberty, the onset of puberty can be

influenced by other factors including nutritional status and chronic illness.

Causes:

1. Constitutional delay

2. Hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism

A/Structural hypothalamic/pituitary disease

B/Functional gonadotrophin deficiency:

Chronic systemic illness (e.g. asthma, malabsorption, coeliac disease, cystic

fibrosis, renal failure)

Psychological stress

Anorexia nervosa

Excessive physical exercise

Hyperprolactinaemia

Other endocrine disease (e.g. Cushing’s syndrome, primary hypothyroidism)

C/Isolated gonadotrophin deficiency (Kallmann’s syndrome)

3. Hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism

• Acquired gonadal damage: Chemotherapy/radiotherapy to gonads

Trauma/surgery to gonads

Autoimmune gonadal failure

Mumps orchitis

Tuberculosis

Haemochromatosis

4. Developmental/congenital gonadal disorders:

Steroid biosynthetic defects

Anorchidism/cryptorchidism in males

Klinefelter’s syndrome (47XXY, male phenotype)

Turner’s syndrome (45XO, female phenotype)

Investigations

Key measurements are LH and FSH, oestradiol (in girls).

Chromosome analysis should be performed if gonadotrophin concentrations are

elevated.

If gonadotrophin concentrations are low, then the differential diagnosis lies

between constitutional delay and hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism.

A plain X-ray of the wrist and hand may be compared with a set of standard

films to obtain a bone age.

Full blood count, renal function, liver function, thyroid function and coeliac

disease autoantibodies should be measured, but further tests may be

unnecessary if the blood tests are normal and the child has all the clinical

features of constitutional delay.

If hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism is suspected, neuroimaging and further

investigations are required.

Management

Puberty can be induced using low doses of oral oestrogen in girls (e.g.

ethinylestradiol 2 μg daily)

Hirsutism:

refers to the excessive growth of terminal hair (the thick,

pigmented hair usually associated with the adult male chest) in an androgen-

dependent distribution in women (upper lip, chin, chest, back, lower abdomen,

thigh, forearm) and is one of the most common presentations of endocrine

disease. It should be distinguished from hypertrichosis, which is generalised

excessive growth of vellus hair (the thin, non-pigmented hair that is typically

found all over the body from childhood onwards).

Approach to patients with hirsuitism

Causes

Clinical features

Ix

Rx

Idiopathic

Often familial

Mediterranean or

Asian background

Normal

Cosmetic

Antiandrogens

PCOS

Obesity

Oligomenorrhoea

or secondary

amenorrhoea

Infertility

LH:FSH ratio >

2.5:1

Minor elevation of

androgens

Mild

hyperprolactinaemia

Wt loss

Cosmetic

measures

Anti-androgens

(Metformin,

glitazones may

be useful

Congenital

adrenal

hyperplasia

(95% 21-

hydroxylase

deficiency

Pigmentation

History of salt-

wasting in

childhood,

ambiguous

genitalia, or

adrenal crisis

when stressed

Jewish

background

Elevated

androgens* that

suppress with

dexamethasone

Abnormal rise in

17-OH-

progesterone with

ACTH

Glucocorticoid

replacement

Exogenous

androgen

administration

Athletes

Virilisation

Low LH and FSH

Analysis of urinary

androgens may

detect drug of

misuse

Stop misuse

Androgen-

secreting

tumour of ovary

or adrenal

cortex

Rapid onset

Virilisation:

clitoromegaly,

deep voice,

balding, breast

atrophy

high androgens*

that do not suppress

with dexamethasone

Low LH and FSH

CT or MRI usually

demonstrates a

tumour

Sx

Cushing’s

S&S of Cushing’s Ix of Cushin’s

Rx of Cushing’s

syndrome

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) affects up to 10% of women of

reproductive age. It is a heterogeneous disorder often associated with obesity,

for which the primary cause remains uncertain. Genetic factors probably play a

role, since PCOS often affects several family members. The severity and

clinical features of PCOS vary markedly between individual patients but

diagnosis is usually made during the investigation of hirsutism or

amenorrhoea/oligomenorrhoea . Infertility may also be present There is no

universally accepted definition but it has been recommended that a diagnosis of

PCOS requires the presence of two of the following three features:

• Menstrual irregularity

• Clinical or biochemical androgen excess

• Multiple cysts in the ovaries (most readily detected by transvaginal

ultrasound)

Women with PCOS are at increased risk of glucose intolerance and some

authorities recommend screening for type 2 diabetes and other cardiovascular

risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome.

Mechanisms*

Manifestations

Pituitary dysfunction

High serum LH High serum prolactin

Anovulatory menstrual cycles

Oligomenorrhoea

Secondary amenorrhoea

Cystic ovaries

Infertility

Androgen excess

Hirsutism

Acne

Obesity

Hyperglycaemia

Elevated oestrogens

Insulin resistance

Dyslipidaemia

Hypertension

Management

1. Wt loss

2. Metformin

3. Antiandrogens

4. Estrogen

5. Local measures