THE LIVER

Anatomy of the liver its parenchyma is entirely covered by a thin capsule and by

visceral peritoneum on all but the posterior surface of the liver, termed the ‘bare area’

The blood supply to the liver is unique, 80 per cent being derived from the portal vein

and 20 per cent from the hepatic artery. The arterial blood supply in most individuals

is derived from the coeliac trunk of the aorta, where the hepatic artery arises along

with the splenic artery.

Structures in the hilum of the liver;

The porta hepatis, a transverse fissure on the visceral surface of the liver, is the

hilum of the liver .The usual anatomical relationship of the structures is for the bile

duct to be within the free edge of the lesser omentum or the ‘hepatoduodenal

ligament’, the hepatic artery to be above and medial, and the portal vein to lie

posteriorly; and together with nerves and lymphatics enter the liver at the porta

hepatis .

SEGMENTAL ANATOMY OF THE LIVER

Couinaud, a French anatomist, described the liver as being divided into eight

segments . Each of these segments can be considered as a functional unit, with a

branch of the hepatic artery, portal vein and bile duct, and drained by a branch of the

hepatic vein. The overall anatomy of the liver is divided into a functional right and

left ‘unit’ along the line between the gall bladder fossa and the middle hepatic vein

(Cantlie’s line). Liver segments (V–VIII), to the right of this line, To the left of this

line (segments I–IV), functionally is the left liver

.

Liver blood supply

_

There are two anatomical lobes with separate blood supply, bile duct and

venous drainage

_

Dual blood supply (20 per cent hepatic artery and 80 per

cent portal vein)

_

The liver regenerates fully after partial resection

_

Resection is based on anatomical lines to preserve maximal functioning liver.

Liver function :Humans will survive for only 24–48 hours in the anhepatic state

despite full supportive therapy. Bilirubin Increased levels may be associated with

increased haemoglobin breakdown, hepatocellular dysfunction resulting in impaired

bilirubin transport and excretion, or biliary obstruction. In patients with known

parenchymal liver disease, progressive elevation of bilirubin in the absence of a

secondary complication suggests deterioration in liver function. The serum alkaline

phosphatase is particularly elevated with cholestatic liver disease or biliary

obstruction. The transaminase levels (aspartate transaminase(AST) and alanine

transaminase (ALT)) reflect acute hepatocellular damage, as does the gamma-

glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) level, which may be used to detect the liver injury

associated with acute alcohol ingestion. The synthetic functions of the liver are

reflected in the ability to synthesise proteins (albumin level) and clotting factors

(prothrombin time). The standard method of monitoring liver function in patients

with chronic liver disease is serial measurement of bilirubin, albumin and

prothrombin time.

Clinical signs of impaired liver function

These signs depend on the severity of dysfunction and whether it is acute or chronic.

Features of

chronic

liver disease_

Lethargy

_

Fever

_

Jaundice

_

Protein

catabolism (wasting)

_

Coagulopathy (bruising)

_

Cardiac (hyperdynamic

circulation )

_

Neurological (hepatic encephalopathy)

_

Portal hypertension

Ascites Oesophageal varices Splenomegaly

_

Cutaneous :Spider naevi

Palmar erythema

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is useful for the staging of hepatopancreatobiliary cancers particularly

primary liver and biliary tract cancers.Lesions overlooked by conventional imaging

are mainly peritoneal metastases and superficial liver tumours. These lesions can be

detected at laparoscopy, thus avoiding an unnecessary laparotomy. A liver biopsy to

confirm or exclude chronic liver disease can also be performed during laparoscopy

LIVER TRAUMA

General

The liver is the second most common organ injured in abdominal trauma..Blunt

injury produces contusion, laceration and avulsion injuries to the liver, often in

association with splenic, mesenteric or renal injury. Penetrating injuries, such as stab

and gunshot wounds, are often associated with chest or pericardial involvement .

Blunt injuries are more common and have a higher mortality than penetrating

injuries.

Summary box 65.7

Diagnosis of liver injury

The liver is an extremely well-vascularised organ, and blood loss is therefore the

major early complication of liver injuries. Clinical suspicion of a possible liver injury

is essential, as a laparotomy by an inexperienced surgeon with inadequate preparation

preoperatively is doomed to failure. All lower chest and upper abdominal stab

wounds should be suspect, especially if considerable blood volume replacement has

been required. Similarly, severe crushing injuries to the lower chest or upper

abdomen often combine rib fractures, haemothorax and damage to the spleen and/or

liver. Focused assessment sonography in trauma (FAST) performed in the emergency

room by an experienced operator can reliably diagnose free intraperitoneal fluid.

Patients with free intraperitoneal fluid on FAST and haemodynamic instability, and

patients with a penetrating wound will require a laparotomy and/or thoracotomy once

active resuscitation is under way. Owing to the opportunity for massive ongoing

blood loss and the rapid development of a coagulopathy, the patient should be

directly transferred to the operating theatre while blood products are obtained and

volume replacement is taking place. Patients who are haemodynamically stable

should have a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest and abdomen as the next step.

This will demonstrate evidence of parenchymal damage to the liver or spleen, as well

as associated traumatic injuries to their feeding vessels. Free fluid can also be clearly

established. The chest scan will help to exclude injuries to the great vessels and

demonstrate damage to the lung parenchyma.

Management of liver trauma

_

Remember associated injuries

_

At-risk groups Stabbing/gunshot in lower chest or upper abdomen

Crush injury with multiple rib fractures

_

Resuscitate

Airway

Breathing

Circulation

_

Assessment of injury : CT chest and abdomen with contrast Laparotomy

if haemodynamically unstable

_

Treatment

Correct coagulopathy

Suture lacerations

Resect if major vascular injury

Packing if diffuse parenchymal injury

Other complications of liver trauma

A subcapsular or intrahepatic haematoma requires no specific intervention and should

be allowed to resolve spontaneously.

Abscesses may form as a result of secondary infection of an area of parenchymal

ischaemia, especially after penetrating trauma. Treatment is with systemic antibiotics

and aspiration under ultrasound guidance once the necrotic tissue has liquefied. Bile

collections require aspiration under ultrasound guidance or percutaneous insertion of

a pigtail drain Late vascular complications include hepatic artery aneurysm and

arteriovenous or arteriobiliary fistulae. These are best treated nonsurgically by a

specialist hepatobiliary interventional radiologist.

CHRONIC LIVER CONDITIONS

There are several chronic liver conditions, which, although rare, are important to

recognise because they require a specific plan for investigation and treatment, and

may present mimickinga more common clinical condition

Important chronic liver conditions.

Condition Common presentations

Budd

–Chiari syndrome Ascites

Primary sclerosing cholangitis(PSC) Abnormal LFTs or

jaundice

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) Malaise, lethargy, itching,

abnormal LFTs

Caroli’s disease Abdominal pain, sepsis

Simple liver cysts Coincidental finding, pain

Polycystic liver disease Hepatomegaly, pain

Budd

–Chiari syndrome

This is a condition principally affecting young females, in which the venous drainage

of the liver is occluded by hepatic venous thrombosis or obstruction from a venous

web. As a result of venous outflow obstruction, the liver becomes acutely congested,

with the development of impaired liver function and, subsequently, portal

hypertension, ascites and oesophageal varices. Treatment of Patients presenting in

fulminant liver failure should be considered for liver transplantation, as should those

with established cirrhosis and the complications of portal hypertension. Those in

whom is not established may be considered for portosystemic shunting by TIPSS,

portocaval shunt or mesoatrial shunting.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

This condition often presents in young adults with mild nonspecific symptoms, and

biliary disease is suggested by the finding of abnormal liver function tests. Rarely, the

first presentation is with jaundice due to biliary obstruction. The disease process

results in progressive fibrous stricturing and obliteration of both the intrahepatic and

the extrahepatic bile ducts

The diagnosis is principally based on the findings at cholangiography,in which

irregular, narrowed bile ducts are demonstrated in both the intrahepatic and the

extrahepatic biliary tree .There is no specific treatment that can reverse the ductal

changes, and the patients usually slowly progress to progressive cholestasis and death

from liver failure. There is a strong predisposition to cholangiocarcinoma (CCA),

Primary biliary cirrhosis

As with PSC, the presentation of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is

often hidden, with general malaise, lethargy and pruritus prior to the development of

clinical jaundice or the finding of abnormal liver function tests. The condition is

largely confined to females. Diagnosis is suggested by the finding of circulating anti-

smooth muscle antibodies and, if necessary, is confirmed by liver biopsy. The

mainstay of treatment is liver transplantation,

Caroli’s disease

This is congenital dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary tree, which is often

complicated by the presence of intrahepatic stone formation. Presentation may be

with abdominal pain or sepsis.Imaging is usually diagnostic, with the finding on

ultrasound or CT of intrahepatic biliary lakes containing stones. Liver transplantation

is a radical but definitive treatment.

Simple cystic disease

Radiological findings to suggest that a cyst is simple are

that it is regular, thin walled and unilocular, with no surrounding tissue response and

no variation in density within the cyst cavity. If these criteria are confirmed and the

cyst is asymptomatic, no further tests or treatment are required. Large cysts may be

associated with symptoms of abdominal discomfort possibly related to stretching of

the overlying liver capsule, acute pain associated with haemorrhage in the cyst, or

may present as right upper quadrant abdominal mass. Aspiration of the cyst contents

under radiological guidance provides a sample for culture, microscopy and cytology,

and allows the symptomatic response to cyst drainage to be assessed.

. Laparoscopic deroofing is the treatment of choice for large symptomatic cysts and is

associated with good long-term symptomatic relief.

Polycystic liver disease

This is a congenital abnormality associated with cyst formation within the liver and

often other abdominal organs, principally the pancreas and kidney. Those associated

with renal cysts may have autosomal dominant inheritance. The cysts are often

asymptomatic and incidental findings on ultrasound. They usually have no effect on

organ function and require no specific treatment .

Ascending cholangitis

Ascending bacterial infection of the biliary tract is usually associated with obstruction

and presents with clinical jaundice, rigors and a tender hepatomegaly. The diagnosis

is confirmed by the finding of dilated bile ducts on ultrasound, an obstructive picture

of liver function tests and the isolation of an organism from the blood on culture. The

condition is a medical emergency, and delay in appropriate treatment results in organ

failure secondary to septicaemia. Once the diagnosis has been confirmed, the patient

should be commenced on a first-line broad-spectrum antibiotic and rehydrated, and

arrangements

should be made for urgent endoscopic or percutaneous transhepatic drainage of the

biliary tree. Biliary stone disease is a common predisposing factor, and the causative

ductal stones may be removed at the time of endoscopic cholangiography by

endoscopic sphincterotomy.

Pyogenic liver abscess

The aetiology of a pyogenic liver abscess is unexplained in themajority of patients. It

has an increased incidence in the elderly, diabetics and the immunosuppressed, who

usually present with anorexia, fevers and malaise, accompanied by right upper

quadrant discomfort. The diagnosis is suggested by the finding of a multiloculated

cystic mass on ultrasound or CT scan and is confirmed by aspiration for culture and

sensitivity. The most common organisms are Streptococcus milleri and Escherichia

coli, but other enteric organisms such as S. faecalis, Klebsiella and Proteus vulgaris

also occur, and mixed growths are common. Opportunistic pathogens include

staphylococci.

Treatment is with antibiotics and ultrasound-guided aspiration. First-line antibiotics

to be used are a penicillin, aminoglycoside and metronidazole or a cephalosporin and

metronidazole. Often, repeated aspirations may be necessary.

Amoebic liver abscess

Entamoeba histolytica exists in vegetative form outside the body . it may also present

with an amoebic abscess, the common

sites being paracaecal and in the liver. The amoebic cyst is ingested and develops into

the trophozoite form in the colon,

and then passes through the bowel wall and to the liver via the portal blood.

Diagnosis is by isolation of the parasite from the

liver lesion or the stool and confirming its nature by microscopy.

Often patients with clinical signs of an amoebic abscess will be treated empirically

with metronidazole (400–800 mg, three

times a day, for 7–10 days) and investigated further only if they do not respond.

Resolution of the abscess can be monitored

using ultrasound.

Hydatid liver disease

. The causative tapeworm, Echinococcus granulosus, is present in the dog intestine,

and ova are ingested by humans and pass in the portal blood to the liver. Liver cysts

are often large by the time of presentation with upper abdominal

discomfort or may present after minor abdominal trauma as an acute abdomen due to

rupture of the cyst into the peritoneal cavity. Diagnosis is suggested by the finding of

a multiloculated cyst on ultrasound and is further supported by the finding of a

floating membrane within the cysts on CT scan .

Active cysts contain a large number of smaller daughter cysts, and rupture can result

in these implanting and growing within the peritoneal cavity. Liver cysts can also

rupture through the diaphragm producing an empyema, into the biliary tract

producing obstructive jaundice, or into the stomach. Clinical and radiological

diagnosis can be supported by serology for antibodies to hydatid antigen in the form

of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Treatment

is

indicated to prevent progressive enlargement and rupture of the cysts. In the first

instance, a course of albendazole or mebendazole may be tried. There are many

reports that percutaneous treatment of hydatid cysts is safe and effective.

Percutaneous treatment constitutes an intial course of albendazole followed by

puncture of the cyst under image guidance, aspiration of the cysts contents,

instillation of hypertonic saline in the cyst cavity and reaspiration (PAIR). PAIR

should only be attempted if there is no communication with the biliary tree. Failure to

respond to medical treatment or percutaneous treatment usually requires surgical

intervention. The surgical options range from liver resection or local excision of the

cysts to deroofing with evacuation of the contents. Contamination of the peritoneal

cavity at the time of surgery with active hydatid daughters should be avoided by

continuing drug therapy with albendazole and adding peroperative praziquantel. This

should be combined with packing of the peritoneal cavity with 20 per cent hypertonic

saline-soaked packs and instilling 20 per cent hypertonic saline into the cyst before it

is opened. A biliary communication should be actively sought and sutured. The

residual cavity may become infected, and this may be reduced, as may bile leakage,

by packing the space with pedicled greater omentum (an omentoplasty). Calcified

cysts may well be dead. If doubt exists as to whether a suspected cyst is active, it can

be followed on ultrasound, as active cysts gradually become larger and more

superficial in the liver. Rupture of daughter hydatids into the biliary tract may result

in obstructive jaundice or acute cholangitis. This may be treated by endoscopic

clearance of the daughter cysts prior to cyst removal from the liver.

Portal Hypertension

The portal venous system contributes approximately 75% of the blood and 72% of the oxygen

supplied to the liver. In the average adult 1000 to 1500 mL/min of portal venous blood is supplied

to the liver. However, this amount can be significantly increased in the cirrhotic patient. The portal

venous system is without valves and drains blood from the spleen, pancreas, gallbladder, and

abdominal portion of the alimentary tract into the liver. The normal portal venous pressure is 5 to 10

mmHg, and at this pressure very little blood is shunted from the portal venous system into the

systemic circulation. As portal venous pressure increases, however, the communications with the

systemic circulation dilate, and a large amount of blood may be shunted around the liver and into

the systemic circulation. Portal Hypertension : direct portal venous pressure that is >5 mmHg

greater than the inferior vena cava (IVC) pressure, a splenic pressure of >15 mmHg, or a portal

venous pressure measured at surgery of >20 mmHg is abnormal and indicates portal hypertension.

A portal pressure of >12 mmHg is necessary for varices to form and subsequently bleed. Ascites

occurs when portal hypertension is particularly high and when hepatic dysfunction is present.

Anorectal varices are present in approximately 45% of cirrhotic patients

.

LIVER TUMOURS

Surgical approaches to resection of liver tumours

Adequate exposure of the liver is an absolute prerequisite to safe liver surgery. A

transverse abdominal incision in the right upper quadrant with a vertical midline

extension to the xiphoid provides excellent access to the liver if adequate retraction of

the costal margin is employed using a costal margin retractor. If necessary,

the incision can be extended across the midline transversely in the left upper

quadrant.

Benign liver tumours

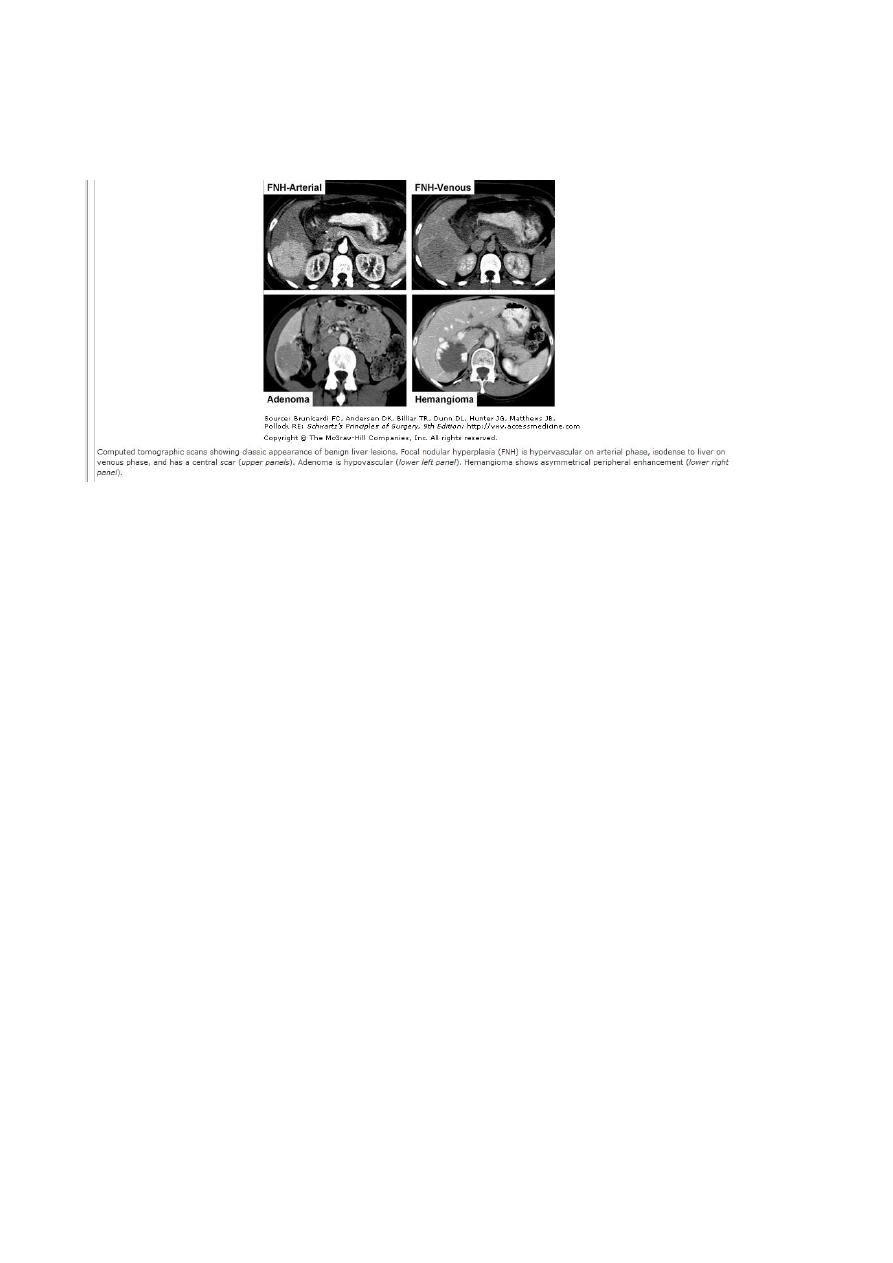

Haemangiomas

These are the most common liver lesions.. They consist of an abnormal plexus of

vessels, and their nature is usually apparent on ultrasound. If diagnostic uncertainty

exists, CT scanning with delayed contrast enhancement shows the characteristic

appearance of slow contrast enhancement due to small vessel uptake in the

haemangioma.Often, haemangiomas are multiple. Lesions found incidentally require

confirmation of their nature and no further treatment.

. Percutaneous biopsy of these lesions should be avoided as they are vascular lesions

and may bleed profusely into the peritoneal cavity.

Hepatic adenoma

. They occur mostly in women of child-bearing age. Imaging byCT or MRI

demonstrates a well-circumscribed and vascular solid tumour. They usually develop

in an otherwise normal liver. Unfortunately, there are no characteristic radiological

features to differentiate these lesions from HCC. An association with sex hormones

(including the oral contraceptive pill) is well recognised, and regression of

symptomatic adenomas on withdrawal of hormone stimulation is well documented.

Focal nodular hyperplasia

This is a focal overgrowth of functioning liver tissue supported by fibrous stroma.

Patients are usually middle-aged

. females, and there is no association with underlying liver disease. Ultrasound shows

a solid tumour mass but does not

help in discrimination. Contrast CT or/and MRI may show central scarring and

evidence of a well-vascularised lesion.

Again, these appearances are not specific for focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). FNH

contain both hepatocytes and Kupffer

cells. MRI using liver-specific contrast agents, such as gadoxetic acid may be useful

in determining the hepatocellular origin of FNH and allowing differentiation of FNH

from metastatic cancer. FNH do not have any malignant potential and, once the

diagnosis is confirmed, they do not require any treatment

Surgery for liver metastases

.

(b

The resectability rate for liver metastases from colorectal cancer is 20–30 per

cent.The expected patient survival rate for resection of colorectal metastases is

approximately 35 per cent at five years, with few cancer-related deaths beyond this

period. Solitary, multiple unilobar and multiple bilobar liver metastases are all

considered

for resection, although cure rates will vary significantly

)

Staging

This involves defining the extent of the liver involvement with metastases and

excluding extrahepatic disease. A standard work up would involve oral and

intravenous contrast CT scans of the liver and abdomen, chest CT scan and

colonoscopy to look for locally recurrent or synchronous colonic cancers. MRI and

PET scanning are useful in the clarification of equivocal lesions. This information

should be taken in parallel with a general medical evaluation before deciding on the

suitability for surgery of an individual patient.. These patients usually have normal

liver parenchyma and therefore tolerate a 60–70 per cent resection of liver

parenchyma without risk of postoperative liver failure (Summary box 65.13).

Tumour markers are useful but have low specificity. Histological confirmation prior

to undertaking surgery is not necessary and percutaneous biopsy of resectable lesions

should be avoided as there is good evidence that malignant cells can seed along the

biopsy track.

Surgical approach

A search for local recurrent disease, peritoneal deposits and regional lymph node

involvement should be made at the start of the laparotomy. Planar imaging often

overlooks peritoneal or superficial liver metastatic deposits. Coeliac node

involvement in patients with liver metastases considerably reduces the overall

survival whether or not the liver and nodal disease is resected. Intraoperative

ultrasound with bimanual palpation of the liver is valuable in assessing the number

of lesions and resectability.

In patients who cannot be rendered resectable, systemic chemotherapy has been

shown to produce survival and quality of life benefit

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Primary liver cancer (HCC) is one of the world’s most commoncancers, and its

incidence is expected to rise rapidly over the next decade due to the association with

chronic liver disease, particularly HBV and HCV. Many patients known to have

chronic liver disease are now being screened for the development of HCC by serial

ultrasound scans of the liver or serum measurements of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP).

Patients often present in middle age, either because of the symptoms of chronic liver

disease (malaise, weakness, jaundice, ascites, variceal bleed, encephalopathy) or with

the anorexia and weight loss of an advanced cancer. The surgical treatment options

include resection of the tumour and liver transplantation. Which option is most

appropriate for an individual patient depends on the stage of the underlying liver

disease, the size and site of the tumour, the availability of organ transplantation and

the management of the immunosuppressed patient.

(a)