DR. JAMAL AL SAIDY

M.B.CH.B…F.I.C.M.S

COXA VARA

The normal femoral neck–shaft angle is 160 degrees at birth, decreasing to 125 degrees in adult life.

An angle of less than 120 degrees is called coxa vara.

The deformity may be:-

o congenital

o acquired due to (Rickets, Perthes disease , Fracture malunion )

CONGENITAL COXA VARA

This is a rare developmental disorder of infancy and early childhood.

It is due to a defect of endochondral ossification in the medial part of the femoral neck.

When the child starts to stand, the femoral neck bends and increasingly collapses into varus and retroversion.

Sometimes there is also shortening or bowing of the femoral shaft.

The condition is bilateral in about one-third of cases.

Clinical features

The condition is usually diagnosed when the child starts to walk.

The leg is short and the thigh may be bowed.

Trendlenburg`s gait

X-rays show that the femoral neck is in varus and abnormally short, and there is a separate fragment of bone in a triangular notch on the

inferomedial surface of the femoral neck. Because of the distorted anatomy, it is difficult to measure the neck–shaft angle. A helpful

alternative is to measure Hilgenreiner’s epiphyseal angle – the angle subtended by a horizontal line joining the centre (triradiate cartilage) of

each hip and another parallel to the physeal line; the normal angle is about 30 degrees while the angle on the abnormal side is much larger

With bilateral coxa vara the patient may not be seen until presents as a young adult with OA.

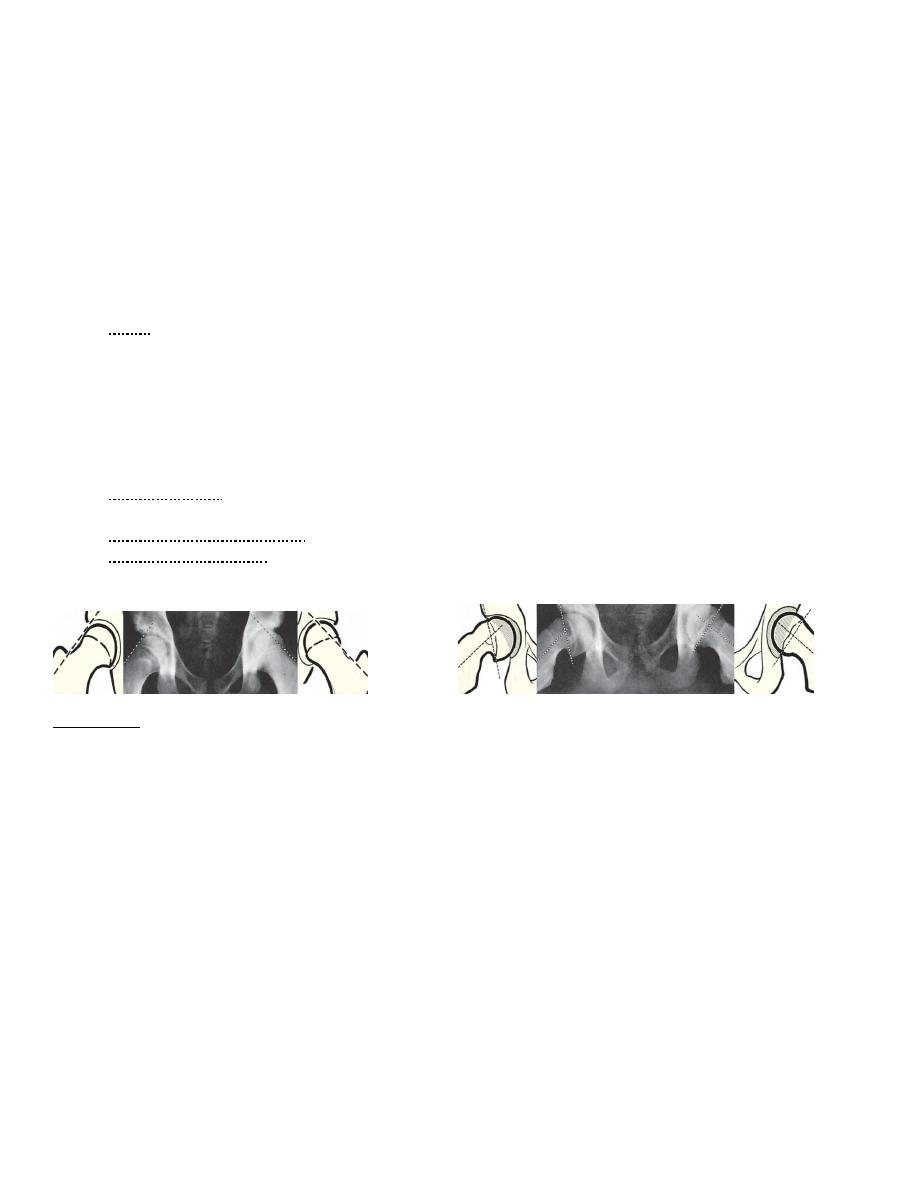

A B C D

Infantile coxa vara

In the normal hip( A) Hilgenreiner

’s epiphyseal angle is well within the normal range of 30–40

The measurements are shown in (B). On the opposite side (C) the physis is too vertical: 45

–60° calls for careful follow-up

and review, and more than 60° is an indication for Pauwels

’ valgus osteotomy. In a neglected case (D) the trochanteric

physis allows further growth but the femoral neck may remain fixed in marked varus.

Treatment…..

If the epiphyseal angle is more than 40 but less than 60 degrees, the child should be kept under observation and re-examined at intervals for

signs of progression.

If it is more than 60 degrees, or if shortening is progressive, the deformity should be corrected by a subtrochanteric or intertrochanteric valgus

osteotomy (Pauwels ).

ACQUIRED COXA VARA

Coxa vara can develop if the femoral neck bends or if it breaks.

A ‘mechanical’ coxa vara sometimes results from severe shortening of the femoral neck.

The patient walks with a severe Trendelenburg gait.

During childhood, coxa vara is seen in rickets and bone dystrophies, and sometimes after Perthes’ disease.

Deformity presenting in adolescence is more likely to be due to epiphysiolysis.

At any age bone ‘softening’ may result in coxa vara; causes include osteomalacia, fibrous dysplasia, pathological fracture or the

aftermath of infection, malunited fractures and Paget’s disease.

Treatment…. Corrective (valgus) osteotomy .

THE IRRITABLE HIP (TRANSIENT SYNOVITIS)

It is transient hip pain & non-specific, short-lived synovitis with restriction of movement and an effusion of the hip joint in

otherwise healthy child

It is the most common cause of an acute limp or hip pain in children( 3–8-year olds ) with a reported frequency of 14 per 1000.

Boys affected twice as often as girls.

It affects both hips in 5 per cent of cases.

Aetiology

unknown

May be transient synovitis due to viral infections, trauma and allergy also have been suggested.

The pathological process involves a synovial effusion resulting in an increased intra-articular pressure.

Clinical features

The typical patient presents with pain and a limp, often intermittent and following activity.

The pain is felt in the groin or front of the thigh, sometimes reaching as far as the knee.

The cardinal sign is restriction of all movements with pain at the extremes of the range in all directions.

A slight wasting may be detectable.

The diagnosis is based primarily on the clinical features.

Standard laboratory investigations including white cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein

concentration are usually within normal limits.

X-rays do not demonstrate any bony defects, but occasionally there may be a little widening of the medial joint space (1–2 mm)

when compared with the unaffected side, due to effusion which can be confirmed by ultrasonography.

Symptoms last for 1–2 weeks and then subside spontaneously.

The child may experience more than one episode, with an interval of months between attacks of pain.

Differential diagnosis

Trauma

Perthes’ disease.

Slipped epiphysis

Tuberculous synovitis.

Juvenile chronic arthritis

Ankylosing spondylitis.

Septic arthritis.

Treatment

Exclude other disorders

Analgesia

Bed rest, reduced activity and observation.

Most children recover within a few days and any deterioration in signs or symptoms requires urgent reassessment.

Traction, although popular not currently recommended as it may increase the intra-articular pressure.

Joint aspiration is ineffective. Ultrasonography is repeated at intervals.

weightbearing is allowed only when the symptoms disappear and the effusion resolves.

This condition carries a good prognosis.

Recurrence rates of up to 10 per cent have been reported.

PERTHES’ DISEASE

It is a painful disorder of childhood characterized by avascular necrosis of the femoral head of unknown cause.

The incidence is about 1 in 10 000 .

Patients are usually 4–10 years old and boys are affected four times as often as girls.

The condition may be part of a general disorder of growth.

Inherited thrombophilia has been postulated as a contributory cause and antithrombotic factor deficiencies and

hypofibrinolysis have been reported in children with Perthes’ disease.

Pathogenesis

The precipitating cause of Perthes’ disease is unknown.

But the cardinal step in the pathogenesis is ischaemia ofthe femoral head.

The immediate cause of capsular tamponade may be an effusion following

o Trauma

o a non-specific synovitis.

two or more such incidents may be needed to produce the typical bone changes.

Pathology

The pathological process goes through several stages which in total may last up to 3 or 4 years.

Stage 1:-…. Ischaemia and bone death

Stage 2: Revascularization and repair : Within weeks (possibly even days) of infarction, a number of

changes begin to appear. Dead marrow is replaced by granulation tissue, which sometimes calcifies. The bone is revascularized

and new lamellae are laid down on the dead trabeculae, producing the appearance of increased density and‘fragmentation’ of

the epiphysis on x-ray.

Stage 3: Distortion and remodelling : the bony epiphysis may collapse and subsequent growth of the femoral head and neck

will be distorted: the head becomes oval or flattened – like the head of a mushroom – and enlarged laterally, while the neck is

often short and broad.

Clinical features

The patient – typically a boy of 4–8 years.

Male > female

Bilateral in 25 %

Pain and limping.

The child appears to be well.

In 4 per cent there is an associated urogenital anomaly.

The hip looks deceptively normal, though there may be a little wasting.

Early on, the joint is irritable so that all movements are diminished and their extremes painful; but abduction

(especially in flexion) is nearly always limited and usually internal rotation also.

X-rays

The radiographic picture varies with the age of the child, the stage of the disease and the amount of head that is necrotic.

At first the x-rays may seem normal.

Necrotic phase : radiographically dense areas due to the new bone formation that always follows bone necrosis.

Fragmentation : alternating patches of density and lucency, or sometimes a crescentic subarticular fracture.

Collapse .

Re-ossification ( Healing ) : Adequate healing

FH spherical, Inadequate healing

FH oval subluxation coxa vara

With

healing the femoral head may regain its normal (or near-normal) shape; however, in less fortunate cases the femoral head becomes mushroom-

shaped.

(a) (b)

Perthes

’ disease – operative treatment (a) The x-ray shows advanced Perthes changes and lateral displacemen of the right femoral head. (b) Following an innominate

osteotomy, the femoral head is much better

‘contained’ and, although not normal, is developing reasonably well.

Differential diagnosis

The irritable hip.

Morquio’s disease.

Cretinism.

multiple epiphyseal dysplasia.

sickle-cell disease.

Gaucher’s disease

Management

Age is the most important prognostic factor: the older the child the less good is the prognosis.

There is a poorer prognosis, too, for girls than for boys.

The initial management of the child with Perthes’ disease is determined by the severity of symptoms.

Analgesia and modification of activities are often sufficient, but hospitalization for bed rest and short periods of

traction are sometimes necessary.

Once joint irritability has subsided, which usually takes about 3 weeks, movement is encouraged, particularly cycling

and swimming.

Preservation of abduction by abduction splint is also important.

The clinical and radiographic features are then reassessed and the choice of further management is between:

(a) symptomatic treatment and (b) containment.

Symptomatic treatment means pain control (if necessary by further spells of traction), gentle exercise to maintain

movement and regular reassessment.

During asymptomatic periods the child is allowed out and about but sport and strenuous activities are avoided.

Containment means taking active steps to seat the femoral head congruently and as fully as possible in the acetabular

socket, so that it may retain its sphericity and not become displaced during the period of healing and remodelling. This

is achieved :-

(a) by holding the hips widely abducted, in plaster or in a removable brace and the position must be

maintained for at least a year); or

(b) by operation, either a varus osteotomy of the femur or an innominate osteotomy of the pelvis, or both.

SLIPPED CAPITAL FEMORAL EPIPHYSIS55

Displacement of the proximal femoral epiphysis – also known as femoral capital epiphysiolysis or slipped capital

femoral epiphysis (SCFE).

Uncommon (1– 3 per 100 000) and virtually confined to children going through the pubertal growth spurt.

Boys (usually between 14 and 16 years old) are affected more often than girls (who are, on average, 2–3 years

younger).

The left hip is affected more commonly than the right and if one side slips there is a 25–40 per cent risk of the other

side also slipping.

The hormonal imbalance as the underlying cause of physeal disruption, and trauma may plays a part, especially in the

30 per cent of cases.

Pathology

In slipped epiphysis the femoral shaft rolls into external rotation and the femoral neck is displaced forwards while the

epiphysis remains seated in the acetabulum. Disruption occurs through the hypertrophic zone of the physis and, the

epiphysis slips posteriorly on the femoral neck.

Clinical features

Acute-on-chronic’ slip.

An initial acute slip occurs in only 15 per cent of cases.

In over 50 per cent of cases there is a history of injury.

The patient is usually a child around puberty, typically overweight or very tall and thin.

The presenting symptom is almost invariably pain, sometimes in the groin, but often only in the thigh or knee.

Limp also occurs early and is more constant.

Characteristically there is limitation of flexion, abduction and medial rotation. Following an acute slip, the hip is

irritable and all movements are accompanied by pain.

Imaging

X-rays In very early cases the x-ray may be reported as ‘normal.

In the anteroposterior view the epiphyseal plate seems to be too wide and too ‘woolly’.

A line drawn along the superior surface of the femoral neck should normally intersect the epiphysis. In an early slip the

epiphysis may be below this line (Trethowan’s sign).

Decreased epiphyseal height, physeal widening, lesser trochanter.

In the lateral view the femoral epiphysis is tilted backwards; this is the most reliable x-ray sign and minor

abnormalities can be detected by measuring the angle subtended by the epiphyseal base and the femoral neck; this is

normally a right angle and anything less than 87 degrees means that the epiphysis is tilted posteriorly.

Ultrasonography Ultrasonography may detect a hip effusion associated with an acute event, and may also show

metaphyseal remodelling in a chronic slip.

Magnetic resonance imaging MRI has been used to detect and stage avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head.

Computed tomography Three-dimensional CT scanning has proved useful in the preoperative planning of realignment

procedures for complex proximal femoral deformities.

(a) (b)

Slipped epiphysis – x-rays (a) Anteroposterior and (b) lateral views of early slipped epiphysis of the right hip. The upper diagrams show Trethowan’s line passing just above

the head on the affected side, but cutting through it on the normal side. The lateral view is diagnostically more reliable; even minor degrees of slip can be shown by drawing

lines through the base of the epiphysis and up the middle of the femoral neck – if the angle indicated is less than 90°, the epiphysis has slipped posteriorly.

Grading

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis can be graded by the clinical presentation and/or radiographic appearance.

The simplest classification is based on the timing of onset:-

o pre-slip.

o Acute.

o Chronic.

o acute-on-chronic.

Radiological grading is based on measurement of the magnitude of the slip relative to the width of the femoral neck,

or the angle of the arc of the slip. On a ‘frog lateral’ x-ray the slip is divided into three stages according to the

percentage slip of the epiphysis in relation to the femoral neck.

o Mild: Displacement is less than one-third of the width of the femoral neck.

o Moderate: Displacement is between one-third and a half.

o Severe: Displacement is greater than half of the femoral neck width.

Treatment

The aims of treatment are

(1) to preserve the epiphyseal blood supply

(2) to stabilize the physis

(3) to correct any residual deformity.

Manipulative reduction of the slip carries a high risk of avascular necrosis and should be avoided.

The choice of treatment depends on the degree of slip:-

Minor slips Deformity is minimal and needs no correction. The position is accepted and the physis is

stabilized by inserting one or two screws or threaded pins along the femoral neck and into the epiphysis,

under fluoroscopic control.

Moderate slips may need a corrective osteotomy.

Severe slips need open reduction and internal fixation by Dunn’s method

Complications

Slipping at the opposite hip. Avascular necrosis

Coxa vara.

Secondary OA.

THANK YOU

DR.JAMAL AL-SAIDY

M.B.CH.B..…… F.I.C.M.S