Pelvic organ prolapse (POP)

The herniation of the pelvic organs to or beyond the vaginal walls is a

common condition. Many women with prolapse experience symptoms

that impact daily activities, sexual function, and exercise. The presence of

POP can have a detrimental impact on body image and sexuality. Its

caused by injury to the muscles or tissues that support the pelvic organs.

TERMINOLOGY

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) – The herniation of the pelvic organs

to or beyond the vaginal walls.

Commonly used terms to describe specific sites of female genital

prolapse include:

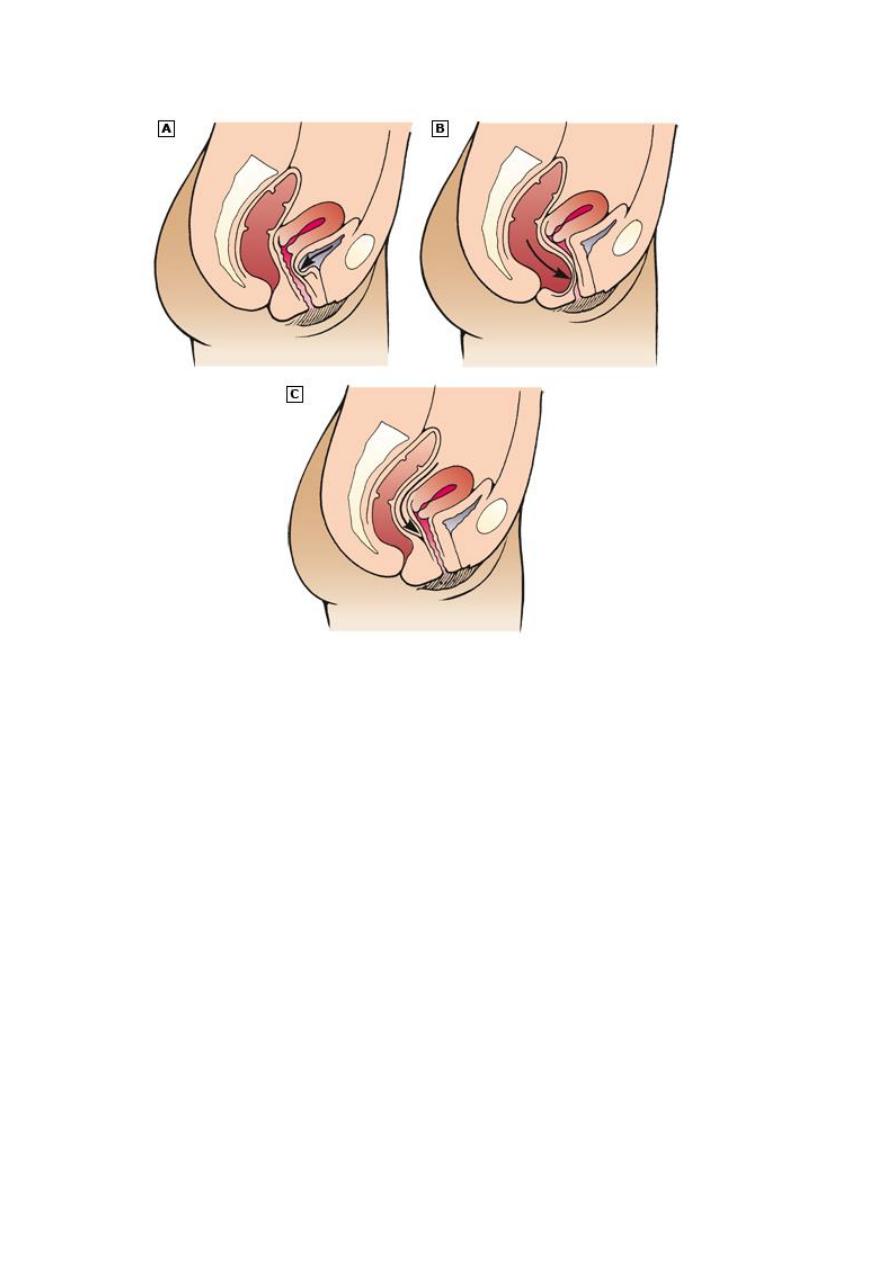

Anterior compartment prolapse – Hernia of anterior vaginal wall

often associated with descent of the bladder (

cystocele

).

Posterior compartment prolapse – Hernia of the posterior vaginal

segment often associated with descent of the rectum (

rectocele

).

Enterocele

– Hernia of the intestines to or through the vaginal wall.

Apical

compartment prolapse (uterine prolapse, vaginal vault

prolapse) – Descent of the apex of the vagina into the lower vagina,

to the hymen, or beyond the vaginal introitus . The apex can be

either the uterus and cervix, cervix alone, or vaginal vault,

depending upon whether the woman has undergone hysterectomy.

Apical prolapse is often associated with enterocele.

Procidentia

— Hernia of all three compartments through the

vaginal introitus.

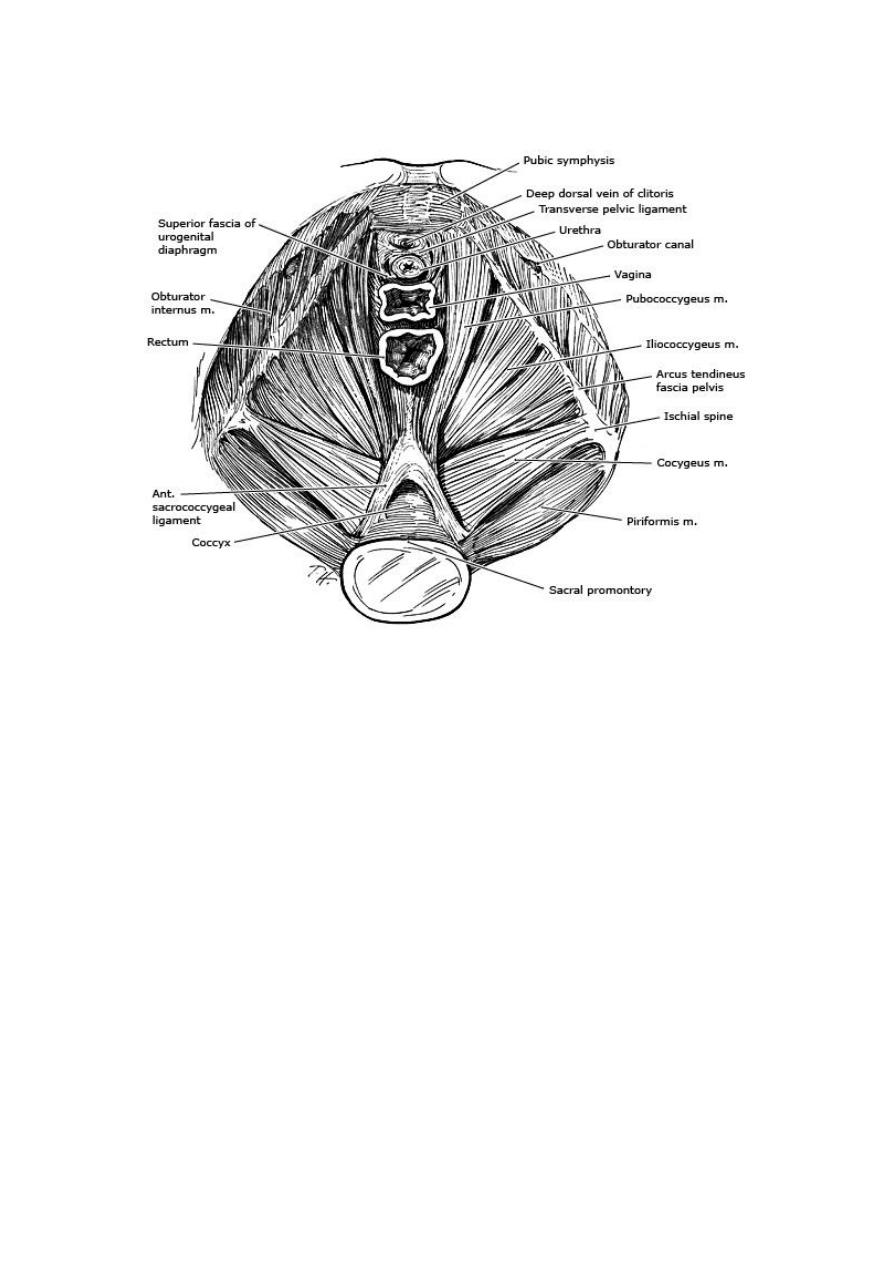

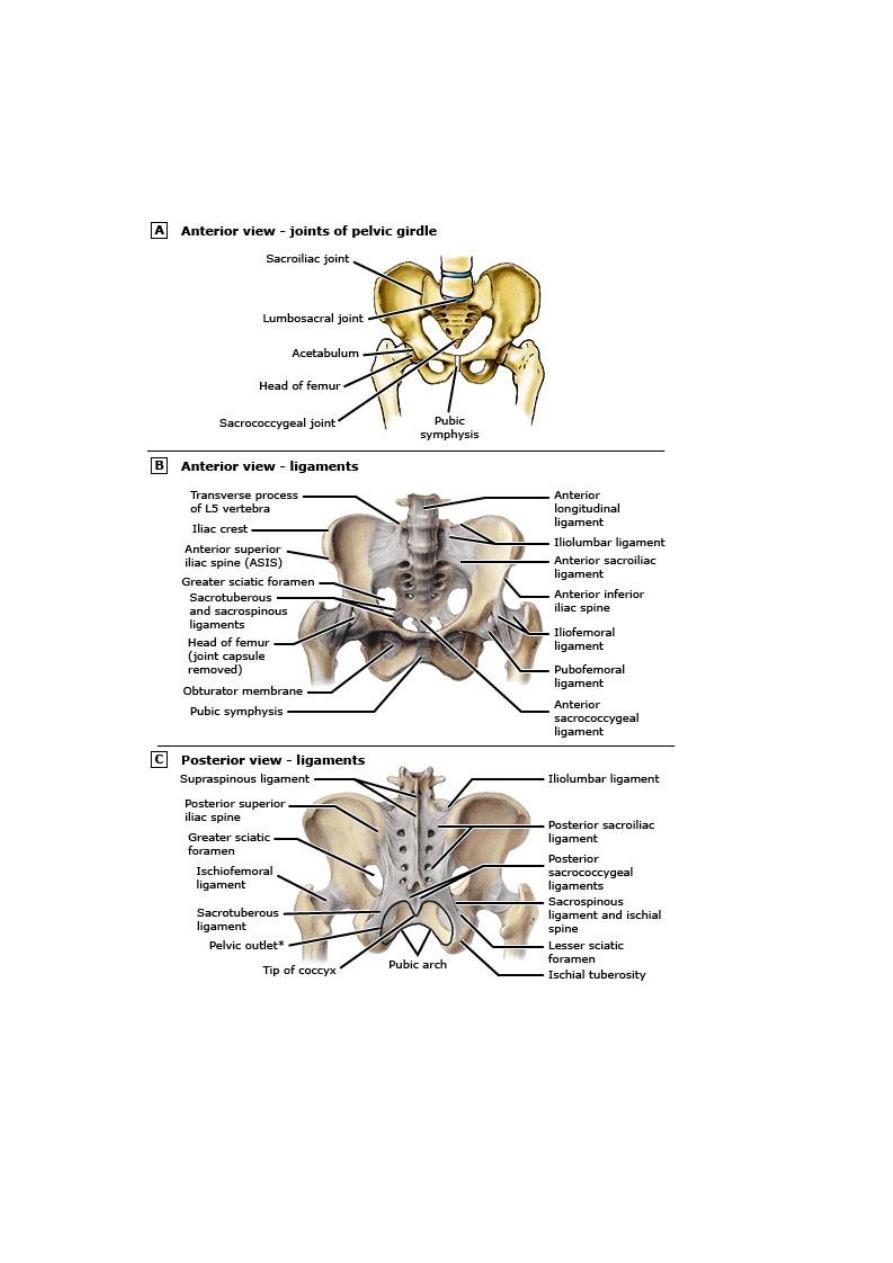

ANATOMY OF PELVIC SUPPORT

Anatomic support of the pelvic organs in women is provided by an

interaction between the muscles of the pelvic floor and connective tissue

attachments to the bony pelvis.

The levator ani muscle complex, consisting of the pubococcygeus,

puborectalis and iliococcygeus muscles, provides primary support to the

pelvic organs, providing firm, yet elastic, based upon which the pelvic

organs rest.

The endopelvic fascial attachments, in particular condensations of the

endopelvic fascia referred to as the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments,

stabilize the pelvic organs correct position so that the pelvic muscles can

provide optimal support in t

he

PREVALENCE

—It about 12-30% in multiparous, and 2% in

nulliparous.

Grading

0-

No prolapse

1-

Leading edge of prolapse str. Descend halfway to vaginal

introitus

2-

Leading edge of prolapse structure descend to vaginal

introitus

3-

Leading edge of prolapse str. Protrude up to half way outside

the vagina

4-

Leading edge protrude up to halfway outside the vagina

RISK FACTORS

— Established risk factors for POP include

parity, advancing age, and obesity

Parity — The risk of POP increases with increasing parity

Obstetric factors in addition to parity can influence the risk of

prolapse. POP can develop during pregnancy prior to delivery.

Vaginal delivery is associated with a higher incidence of POP than

cesarean.

Advancing age — Older women are at an increased risk for POP

Obesity — Overweight and obese women (body mass index >25)

have a two-fold higher risk of having prolapse than other women.

While weight gain is a risk factor for developing prolapse, it is

controversial whether weight loss results in prolapse regression.

However, there are reports of POP regression in women after

bariatric surgery.

Hysterectomy — Hysterectomy is associated with an increased risk

of apical prolapse. Factors that may influence the risk of prolapse

after hysterectomy are age and the surgical route (abdominal or

vaginal).

Race and ethnicity — Data suggest that African-American women

have a lower prevalence of symptomatic POP than other racial or

ethnic groups in the US.

Other risk factor — chronic constipation is a risk factor for POP,

likely due to repetitive increases in intraabdominal pressure, the

risk of prolapse is increased in women with occupations that

involve heavy lifting.

Some connective tissue disorders (eg, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) or

congenital abnormalities (eg, bladder exstrophy) contribute to POP.

Endocrine (menstrual cycle, pregnancy and menopause) are the

most significant endocrine event effect pelvic floor fascia, that is

why POP more evident in mense, pregnancy(effect of

progesterone)

PREVENTION

— Prolapse prevention strategies have not been

extensively studied. Although vaginal childbirth is associated with

an increased risk of prolapse, it is unclear that cesarean delivery

will prevent the occurrence of prolapse.

Prevention of progression of prolapse has not been well studied.

Some data suggest that women with prolapse who use a vaginal

pessary have a lower stage of prolapse on subsequent exams.

Interventions such as weight loss, treatment of chronic

constipation, and avoidance of jobs that require heavy lifting are

potential interventions to avoid the development or progression of

POP and deserve further investigation.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Patients with POP may present with symptoms related specifically to the

prolapsed structures, such as a bulge or vaginal pressure or with

associated symptoms including urinary, defecatory or sexual dysfunction.

Symptoms such as low back or pelvic pain have often been attributed to

POP.

Severity of symptoms does not correlate well with the stage of

prolapse. Symptoms are often related to position; they are often

less noticeable in the morning or while supine and worsen as the

day progresses.

Many women with prolapse are asymptomatic; treatment is

generally not indicated in these women.

Bulge or pressure symptoms — Women with POP often present

with the complaint of vaginal or pelvic pressure and/or the

sensation of a vaginal bulge or something falling out of the vagina.

Some women are able to see a protrusion of the prolapse beyond

the introitus (procidentia).

Protrusion of the vagina may result in chronic discharge and/or

bleeding from ulceration.

Urinary symptoms — Loss of support of the anterior vaginal wall

or vaginal apex may affect bladder and/or urethral function.

Symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) often coexist with

stage I or II prolapse, obstructive symptoms, incomplete bladder

empyting , urinary retention.

Women with POP have a two- to five-fold risk of overactive

bladder symptoms (urgency, urge urinary incontinence, frequency)

compared with the general population.

In addition, some women with POP experience enuresis or

incontinence with sexual intercourse.

Defecatory symptoms — the most common bowel symptom

associated with prolapse is constipation. Other defecatory

symptoms include fecal urgency and fecal incontinence and

obstructive symptoms, eg, incomplete emptying, straining, or the

need to apply digital pressure to the vagina or perineum (splint) to

completely evacuate; some women report fecal incontinence during

sexual intercourse.

Effects on sexual function — Prolapse does not appear to be

associated with decreased sexual desire or with dyspareunia,

DIAGNOSIS AND CLASSIFICATION

POP is diagnosed using pelvic examination. A medical history is

also important to elicit prolapse-associated symptoms, since

treatment is generally indicated only for symptomatic prolapse, the

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantitation (POPQ) system has become

the most commonly used prolapse staging system.

NATURAL HISTORY — Prolapse has traditionally been regarded

as a progressive disease, with mild prolapse leading to more

advanced disease. However, data suggest that the course is

progressive until menopause, after which the degree of prolapse

may follow a course of alternating progression and regression.

Examination

Pelvic examination by sims speculum for assesment of pop

grading.

APPROACH TO MANAGEMENT

Indications for treatment — Treatment is indicated for women with

symptoms of prolapse or associated conditions (urinary, bowel, or

sexual dysfunction). Obstructed urination or defecation or

hydronephrosis from chronic ureteral kinking are all indications for

treatment, regardless of degree of prolapse.

Treatment is generally not indicated for women with asymptomatic

prolapse.

Establishing patient goals — Treatment is individualized

according to each patient’s symptoms and their impact on her

quality of life.

Management options — Women with symptomatic prolapse can be

managed expectantly, or treated with conservative or surgical

therapy

The choice of therapy depends upon the patient’s preferences, as

well as the ability to comply with conservative therapy or tolerate

surgery. Some data suggest that age, the degree of POP as

measured by descent of leading edge of prolapse, preoperative

pelvic pain scores, and prior prolapse surgery are independently

associated with treatment choices.

Expectant management — Expectant management is a viable

option for women who can tolerate their symptoms and prefer to

avoid treatment.

Women with symptomatic or asymptomatic prolapse who decline

treatment, particularly stage III or IV, should be evaluated on a

regular basis to assess for the development or worsening of urinary

or defecatory symptoms.

Conservative management — Conservative therapy is the first line

option for all women with POP, since surgical treatment incurs the

risk of complications and recurrence. However, prolapse is

typically a chronic problem, and many women ultimately prefer

surgery to conservative therapy since successful surgery does not

require ongoing maintenance.

Vaginal pessary — the mainstay of non-surgical treatment for POP

is the vaginal pessary. Pessaries are silicone devices in a variety of

shapes and sizes, which support the pelvic organs. Approximately

half of the women who use a pessary continue to do so in the

intermediate term of one to two years. Pessaries must be removed

and cleaned on a regular basis.

Need replacement every 6 months, shelf pessary used in

hysterectomised patient, pt. do not desired sexual function and

incase of vaginal ulceration and infection.

Indication for pessary: pt. wish, as therapeutic test, child bearing

not completed, medically unfit, during and after pregnancy, while

waiting for surgery.

Pelvic floor muscle exercises — pelvic floor muscle exercises

(PFME) appear to result in improvements in POP stage and POP-

associated symptoms.

Estrogen therapy — There are few data about the use of estrogen

therapy for treatment of symptomatic POP. Use of estrogenic

agents (raloxifene) appears to be associated with a decrease in

undergoing surgery for POP.

Surgical treatment — Surgical candidates include women with

symptomatic prolapse who have failed or declined conservative

management of their prolapse. There are numerous surgeries for

prolapse including vaginal and abdominal approaches with and

without graft materials.

Surgical prognosis depends upon the severity of symptoms, extent

of the prolapse, physician experience, and patient expectations.

Surgery has traditionally been associated with a

recurrence/reoperation rate of up to 30%.

Utero vaginal prolapse

If the woman not wish to conserve her uterus: vaginal hysterectomy

with adequate support of the vault to the uterosacral ligament is

sufficient.

If wish to conserve uterus 1- Manchester op.

2- Sacrohysteropexy

Vault prolapse

sacrocolpopexy, sacrospinous ligment fixation

Cystourethroceole

(anterior colporphy) done if no concurrent stress

incontinence.

Rectocele

(posterior colporaphy)

Enterocele

the peritoneal sac contain small bowel should be excised,

POD closed by approximating the peritoneum and utero sacral

ligament.

Colpocleisis

closure of vagina