1

Hepatitis Viruses

Viral hepatitis is a clinical diagnosis and presents as a systemic infection primarily

affecting the liver or as part of a general systemic infection. Hepatitis A, B, C, D and

E viruses are all hepatotropic viruses and primarily cause hepatic infection, whereas

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and other viruses may cause

hepatitis as part of a more generalized systemic infection. The differential diagnosis

should also include non-viral causes such as leptospirosis.

Differential diagnosis

Viral causes of hepatitis

_ Infection with hepatotropic viruses:

hepatitis A virus

hepatitis B virus

hepatitis C virus

hepatitis D virus

hepatitis E virus

_ Infection with other viruses:

cytomegalovirus (CMV)

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)

rubella virus

_ Infection with ‘exotic viruses’:

yellow fever virus

hantavirus

Lassa virus

Marburg and Ebola viruses

Junin and Machupo viruses

Kyasanur Forest virus

Other non-viral infective causes

, such as leptospira, rickettsia including Coxiella,

bacterial cholangitis

Non-infective causes

, such as drugs, alcohol, metabolic liver disease, autoimmune

liver disease, cryptogenic hepatitis, obstructive hepatitis

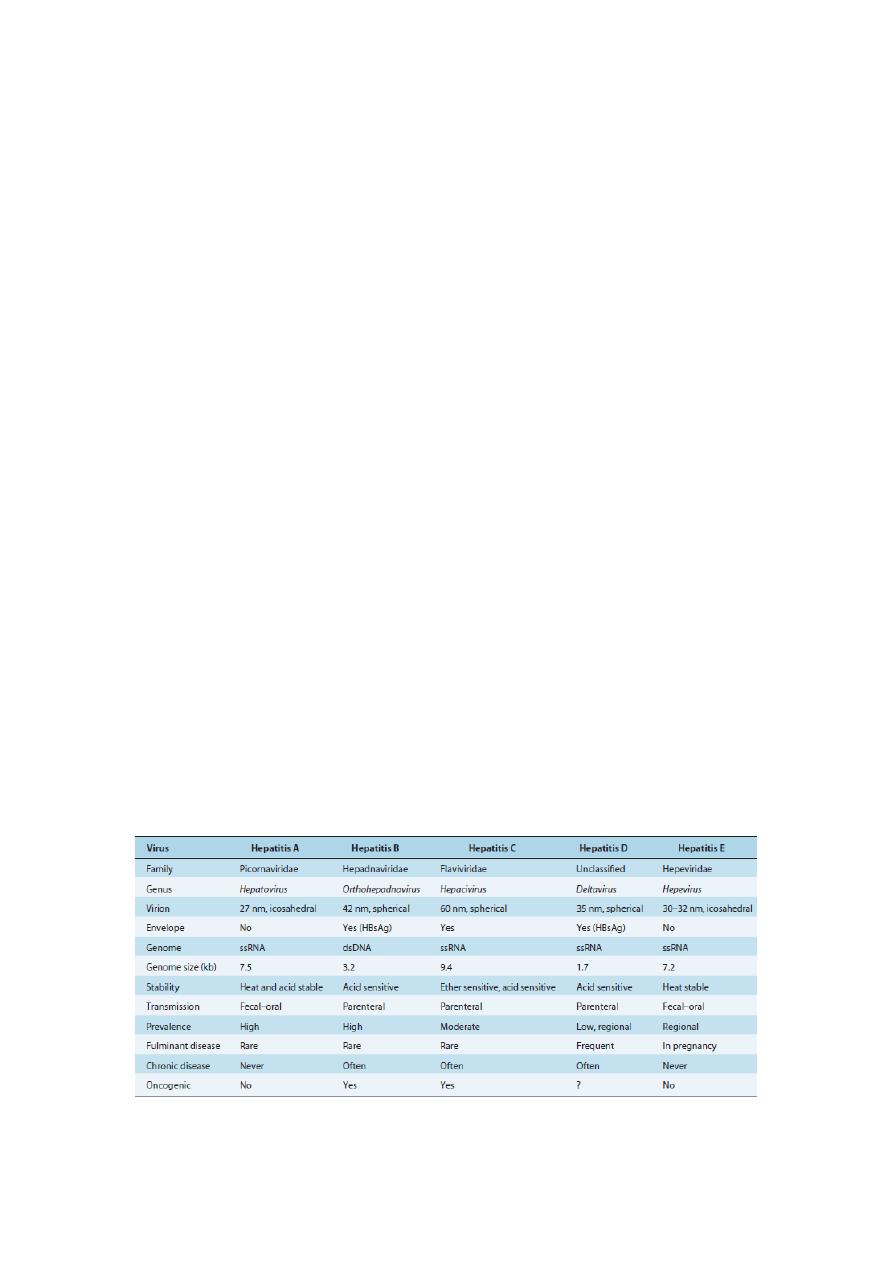

Table 1

Characteristics of Hepatitis Viruses

ds, double stranded; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; ss, single stranded.

2

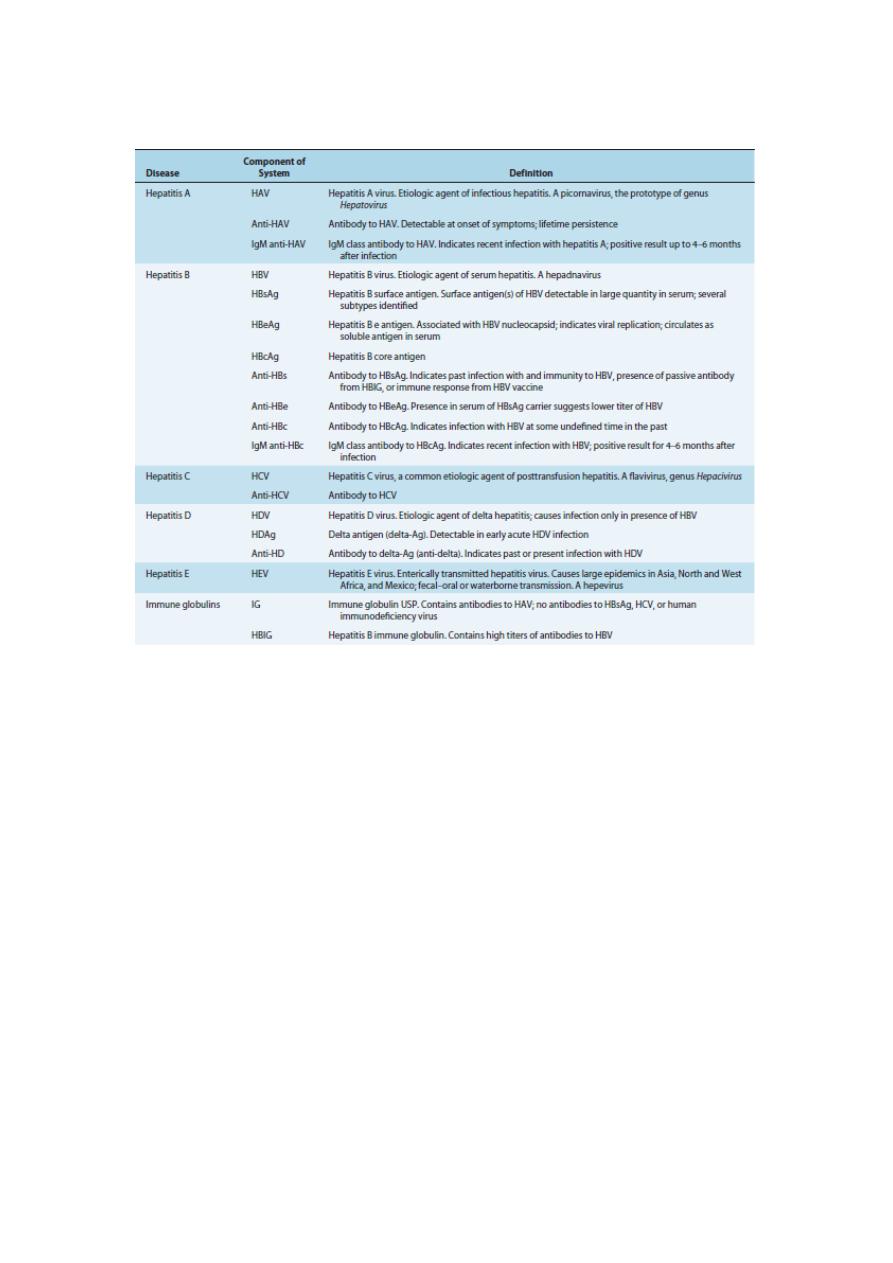

Table 2

Nomenclature and Definitions of Hepatitis Viruses, Antigens, and Antibodies

Hepatitis A (sometimes called infectious hepatitis) and hepatitis E are transmitted by

fecal-oral contamination. The other major types include hepatitis B (sometimes called

serum hepatitis), hepatitis C (formerly non-A, non-B hepatitis), and hepatitis D (a

virusoid formerly called delta hepatitis).

Hepatitis

A

Hepatitis A virions were first identified in the stool of patients by electron microscopy in

1973

.

Hepatitis A (infectious hepatitis) usually is transmitted by fecal-oral contamination of

food, drink, or shellfish that live in contaminated water and contain the virus in their

digestive system.

The disease is caused by the hepatitisAvirus (HAV) of the genus Hepatovirus in the

family Picornaviridae. The hepatitis A virus is an icosahedral, linear, positive-strand

RNA virus that lacks an envelope.

Once in the digestive system, the viruses multiply within the intestinal epithelium.

Usually only mild intestinal symptoms result.

Occasionally viremia (the presence of viruses in the blood) occurs and the viruses

may spread to the liver.

The viruses reproduce in the liver, enter the bile, and are released into the small

intestine. This explains why feces are so infectious.

Symptoms last from 2 to 20 days and include anorexia, general malaise, nausea,

diarrhea, fever, and chills.

If the liver becomes infected, jaundice ensues.

3

Laboratory diagnosis is by detection of anti-hepatitis A antibody.

During epidemic years, about 30,000 cases were reported annually in the United

States.

The number of new cases has been dramatically reduced since the introduction of the

hepatitis A vaccine in the 1990s.

Fortunately the mortality rate is low (less than 1%), and infections in children are

usually asymptomatic.

Most cases resolve in 4 to 6 weeks and yield a strong immunity.

Approximately 40 to 80% of the United States population have serum antibodies

though few have been aware of the disease.

Control of infection is by simple hygienic measures, the sanitary disposal of excreta,

and the killed HAV vaccine (Havrix).

This vaccine is recommended for travelers going to regions with high evidence rates

of hepatitis A.

Hepatitis E

The HEV particles were first recovered from the stool of patients in Tashkent, Uzbekistan in

1983

.

Hepatitis E is implicated in many epidemics in certain developing countries in Asia,

Africa, and Central and South America.

It is uncommon in the United States but is occasionally imported by infected travelers.

The monopartite, positive-strand, RNA viral genome (7,900 nucleotides) is linear.

The virion is spherical, nonenveloped, and 32 to 34 nm in diameter.

Based on biologic and physicochemical properties, HEV has been provisionally

classified in the Caliciviridae family; however, the organization of the HEV genome

is substantially different from that of other caliciviruses and, therefore, HEV may

eventually be classified in a separate family. In recent years, HEV has been classified

in the Hepeviridae family.

Infection usually is associated with feces-contaminated drinking water. Presumably

HEV enters the blood from the gastrointestinal tract, replicates in the liver, is released

from hepatocytes into the bile, and is subsequently excreted in the feces.

Like hepatitis A, an HEVinfection usually runs a benign course and is selflimiting.

The incubation period varies from 15 to 60 days, with an average of 40 days.

The disease is most often recorded in patients that are 15 to 40 years of age.

Children are typically asymptomatic or present mild signs and symptoms, similar to

those of other types of viral hepatitis, including abdominal pain, anorexia, dark urine,

fever, hepatomegaly, jaundice, malaise, nausea, and vomiting.

Case fatality rates are low (1 to 3%) except for pregnant women (15 to 25%), who

may die from fulminant hepatic failure.

Diagnosis of HEV is by ELISA (IgM or IgG to recombinant HEV) or reverse

transcriptase PCR. There are no specific measures for preventing HEV infections

other than those aimed at improving the level of health and sanitation in affected

areas.

Hepatitis B (serum hepatitis) is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), an enveloped,

double-stranded circular DNA virus of complex structure. HBV is classified as an

Orthohepadnavirus within the family Hepadnaviridae. Serum from individuals

infected with hepatitis B contains three distinct antigenic particles:

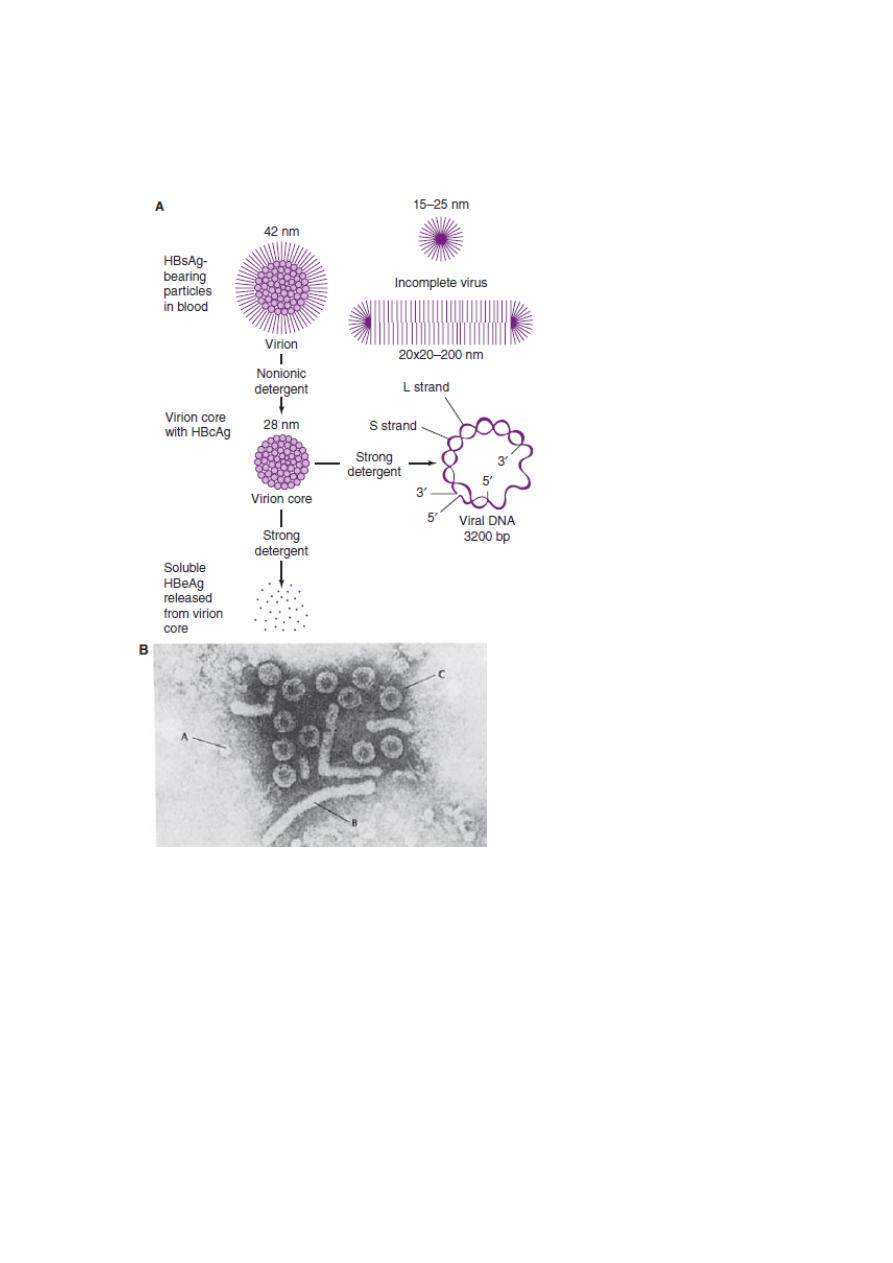

4

a spherical 22 nm particle, a 42 nm spherical particle (containing DNA and DNA

polymerase) called the Dane particle, and tubular or filamentous particles that vary in

length (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Hepatitis B viral and subviral forms.

A: Schematic representation of three hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)- containing forms that

can be identified in serum from hepatitis B virus (HBV) carriers. The 42-nm spherical Dane

particle can be disrupted by nonionic detergents to release the 28-nm core that contains the

partially double-stranded viral DNA genome. A soluble antigen, termed hepatitis B e antigen

(HBeAg), may be released from core particles by treatment with strong detergent. HBcAg,

hepatitis B core antigen.

B: Electron micrograph showing three distinct HBsAg-bearing forms: 20-nm pleomorphic

spherical particles (A), filamentous forms (B), and 42-nm spherical Dane particles, the infectious

form of HBV (C).

5

The viral genome is 3.2 kb in length, consisting of four partially overlapping, open-

reading frames that encode viral proteins.

Viral replication takes place predominantly in hepatocytes.

The infecting virus encases its double-shelled Dane particles within membrane

envelopes coated with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). The inner nucleocapsid

core antigen (HBcAg) encloses a single molecule of double-stranded HBV DNA and

an active DNA polymerase. HBsAg in body fluids is (1) an indicator of hepatitis B

infection, (2) used in the large-scale screening of blood for the hepatitis B virus, and

(3) the basis for the first vaccine for human use developed by recombinant DNA

technology.

Diagnosis of HBV is made by detection of HBsAg in unimmunized individuals or

HBcAg antibody, or detection of HBV nucleic acid by PCR.

The hepatitis B virus is normally transmitted through blood or other body fluids

(saliva, sweat, semen, breast milk, urine, feces) and body-fluid-contaminated

equipment (including shared intravenous needles).

The virus can also pass through the placenta to the fetus of an infected mother.

The HBV is transmitted more easily than HIV or HCV.

A particular characteristic of chronic HBV is the production of large quantities of

subviral particles containing only envelope antigens and associated host- derived

lipid. These particles are present in a 10

3

- 10

6

- fold excess over virions and may

constitute a way of subverting the antiviral response

In the United States, about 5,000 persons die yearly from hepatitis-related cirrhosis

and about 1,000 die from HBV-related liver cancer. (HBV is second only to tobacco

as a known cause of human cancer.) Worldwide, HBV infects over 200 million

people.

The clinical signs of hepatitis B vary widely.

Most cases are asymptomatic. However, sometimes fever, loss of appetite, abdominal

discomfort, nausea, fatigue, and other symptoms gradually appear following an

incubation period of 1 to 3 months.

The virus infects liver hepatic cells and causes liver tissue degeneration and the

release of liver-associated enzymes (transaminases) into the bloodstream.

This is followed by jaundice, the accumulation of bilirubin (a breakdown product of

hemoglobin) in the skin and other tissues with a resulting yellow appearance.

Chronic hepatitis B infection also causes the development of primary liver cancer,

known as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Hepatocellular carcinoma is one of the most common cancers worldwide, and HBV is

responsible for at least 80 % of these cancers.

Development of HCC in hepatitis B patients does not require proceeding cirrhosis.

Hence, it is advocated that all HBV infected patients, regardless of cirrhosis status,

should get screening for HCC every 6 months.

The HBV DNA template is transcribed by cellular RNA polymerase to progenic

RNA, which in turn is reverse transcribed to DNA by virus polymerase. This unique

way of HBV replication means a significant tendency to mutation. Hepatitis B virus

has a reported mutation rate of 10 times greater compare with other DNA viruses.

6

Chronicity is dependent mostly upon age at exposure. Clinically, it is estimated that

5% to 10% of HBV-infected adults will develop chronic hepatitis. In contrast, nearly

90% of perinatal infections are chronic.

General measures for prevention and control involve (1) excluding contact with HBV-

infected blood and secretions, and minimizing accidental needle-sticks; (2) passive

prophylaxis with intramuscular injection of hepatitis B immune globulin within 7

days of exposure; and (3) active prophylaxis with recombinant vaccines: Energix-B,

Recombivax HB, Pediatrix, and Twinrix.

These vaccines are widely used and are recommended for routine prevention of HBV

in infants to 18-year-olds, and risk groups of all ages (for example, household

contacts of HBV carriers, healthcare and public safety professionals, men who have

sex with other men, international travelers, hemodialysis patients).

Recommended treatments for HBV include Adefovir dipivoxil, alpha-interferon, and

lamivudine.

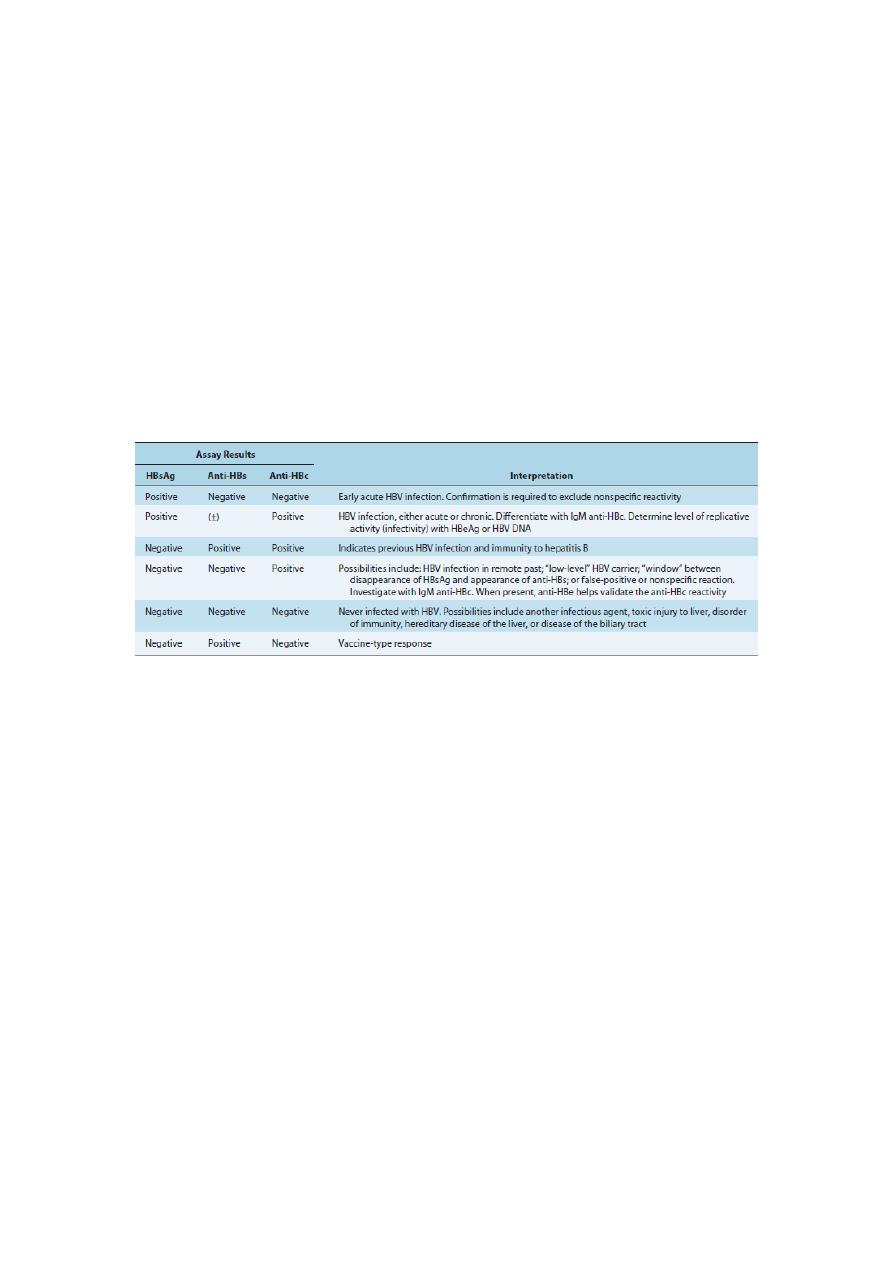

Table 3

Interpretation of Hepatitis B Virus Serologic Markers in Patients with Hepatitis

Anti-HBc,antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; anti-HBe, antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; anti-HBs, antibody to

hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg); HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; IgM, immunoglobulin

M.

Hepatitis C is caused by the enveloped hepatitis C virus (HCV), which has an 80 nm

diameter, a lipid coat, contains a single strand of linear RNA.

The hepatitis C virus is a member of the family Flaviviridae. HCV is classified into

multiple genotypes.

This virus is transmitted by contact with virus-contaminated blood, by the fecal-oral

route, by in utero transmission from mother to fetus, sexually, or through organ

transplantation.

Diagnosis is made by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which detects

serum antibody to a recombinant antigen of HCV, and nucleic acid detection by PCR.

HCV is found worldwide.

Prior to routine screening, HCV accounted for more than 90% of hepatitis cases

developed after a blood transfusion.

About 80 % of patients with acute hepatitis C will develop chronic HCV, of about 20-

30 % will progress to cirrhosis and its consequences, over 10-20 years. After 20- 40

years, a small proportion of patients with chronic disease will develop HCC.

Worldwide, hepatitis C has reached epidemic proportions, with more than 1 million

new cases reported annually. In the United States, nearly 4 million persons are

infected and 25,000 new cases occur annually.

Currently, HCV is responsible for about 8,000 deaths annually in the United States.

Furthermore, HCV is the leading reason for liver transplantation in the United States.

7

Treatment is with Ribovirin and pegylated (coupled to polyethylene glycol)

recombinant interferon-alpha (Intron A, Roferon-A).

This combination therapy can rid the virus in 50% of those infected with genotype 1

and in 80% of those infected with genotype 2 or 3.

In 1977 a cytopathic hepatitis agent termed the Delta agent was discovered by

Mario

Rizzetto and colleagues

. Later it was called the hepatitis D virus (HDV) and the disease

hepatitis D was designated. HDV is a unique agent in that it is dependent on the

hepatitis B virus to provide the envelope protein (HBsAg) for its RNA genome. Thus

HDV only replicates in liver cells co-infected with HBV. Both must be actively

replicating. Furthermore, the RNA of the HDV is smaller than the RNA of the

smallest picornaviruses and its circular conformation differs from the linear structure

typical of animal RNA viruses. Thus its similarity to the plant virusoids has led some

to also call this agent a virusoid. HDV is spread only to persons who are already

infected with HBV (superinfection) or to individuals who get HBV and the virusoid at

once (coinfection). The primary laboratory tools for the diagnosis of an HDV

infection are serological tests for anti-delta antibodies.

Treatment of patients with chronic HDV remains difficult.

Some positive results can be obtained with alpha interferon treatment for 3 months to

1 year.

Liver transplantation is the only alternative to chemotherapy.

Worldwide, there are approximately 300 million HBV carriers, and available data

indicate that no fewer than 5% of these are infected with HDV. Thus because of the

propensity of HDV to cause fulminant as well as chronic liver disease, continued

incursion of HDV into areas of the world where persistent hepatitis B infection is

endemic has serious implications.

Prevention and control involves the widespread use of the hepatitis B vaccine.

8

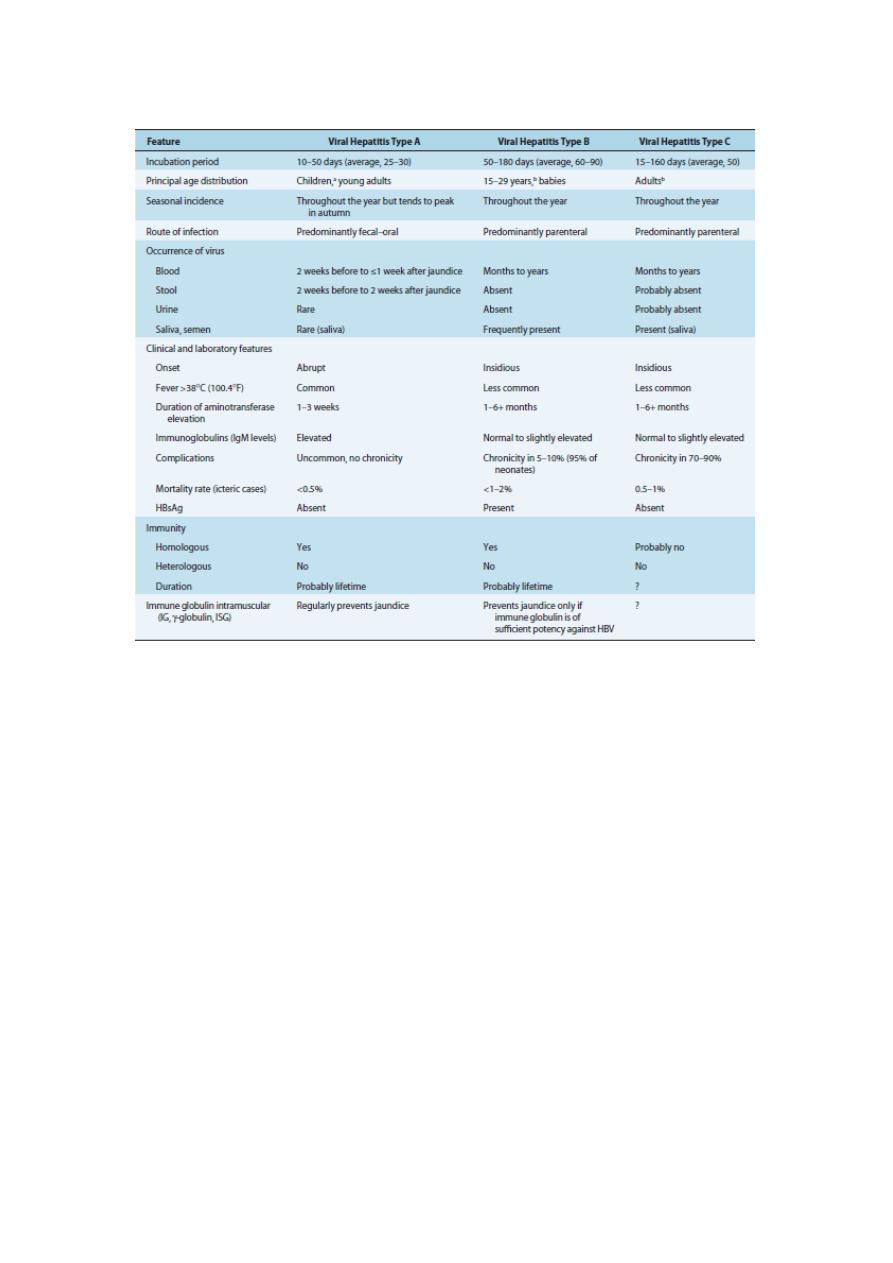

Table 4

Epidemiologic and Clinical Features of Viral Hepatitis Types A, B, and C

a

Nonicteric hepatitis is common in children.

b

Among the age group 15–29 years, hepatitis B and C are often associated with drug abuse or

promiscuous sexual behavior. Patients with transfusion-associated hepatitis B or C virus are generally

older than age 29 years.

HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; IG, immune globulin; IgM,

immunoglobulin M; ISG, immune serum globulin.

9

Two other forms of hepatitis have been identified: hepatitis F (causing fulminant,

posttransfusion hepatitis) and a syncytial giant-cell hepatitis (hepatitis G) with

viruslike particles resembling the measles virus.

Further virologic, epidemiological, and molecular efforts to characterize these new

agents and their diseases are currently being undertaken.

In 1994, French researchers reported the isolation of an enteric agent responsible

for sporadic cases of non-A to E hepatitis and named the hepatitis F virus (HFV), for

hepatitis French virus. However, their findings have not been confirmed by others and

the term HFV is currently unclaimed.

Hepatitis G virus (HGV) was first isolated in 1995 from a surgeon with infective

jaundice of unknown cause. It is a single- stranded RNA virus that is included in the

Flaviviridae family and shares a 27% homology with HCV. It has been cloned and is

widely distributed in humans. HGV can be transmitted through needles or sexually.

Infection causes chronic liver inflammation with its associated sequelae.

Torque Teno virus

or

TT virus (TTV) is a naked, circular, non-enveloped virus

with a single- stranded DNA genome, suggested to be a member of Circoviridae

family. It was first identified in 1997 and named after the initial index of Japanese

patient who was suffering with post transfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology.

In July 1999, the recent data from the Diasorin Research Center in Bresica, Italy

documented a novel virus, provisionally named SEN-V.

The SEN-V virus is a member of the TT virus superfamily. It is a single-stranded,

circular DNA virus of the Circoviridae family. The virus is parenterally transmitted,

and appears capable of co-infecting patients who have other types of viral disease

raising the possibility that it may aggravate their clinical course.