Coccidioidomycosis

(San Joaquin Fever; Valley Fever)

Coccidioidomycosis is a pulmonary or hematogenously spread disseminated disease

caused by the fungi Coccidioides immitis and C. posadasii; it usually occurs as an

acute benign asymptomatic or self-limited respiratory infection. The organism

occasionally disseminates to cause focal lesions in other tissues. Symptoms, if

present, are those of lower respiratory infection or low-grade nonspecific

disseminated disease. Diagnosis is suspected based on clinical and epidemiologic

characteristics and confirmed by chest x-ray, culture, and serologic testing. Treatment,

if needed, is usually with fluconazole, itraconazole, newer triazoles, or amphotericin

B.

(See also the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s

In North America, the endemic area for coccidioidomycosis includes

The southwestern US

Northern Mexico

The affected areas of the southwestern US include Arizona, the central valley of

California, parts of New Mexico, and Texas west of El Paso. The area extends into

northern Mexico, and foci occur in parts of Central America and Argentina. About 30

to 60% of people who live in an endemic region are exposed to the fungus at some

point during their life. In the US, about 150,000 infections develop annually; over half

of them are subclinical.

Pathophysiology

Infections are acquired by inhaling spore-laden dust. Thus, certain occupations (eg,

farming, construction) and outdoor recreational activities increase risk. Epidemics can

occur when heavy rains, which promote the growth of mycelia, are followed by

drought and winds. Because of travel and delayed onset of clinical manifestations,

infections can become evident outside endemic areas.

Once inhaled, C. immitis spores convert to large tissue-invasive spherules. As

spherules enlarge and then rupture, each releases thousands of small endospores,

which may form new spherules. Pulmonary disease is characterized by an acute,

subacute, or chronic granulomatous reaction with varying degrees of fibrosis. Lesions

may cavitate or form nodular-like coin lesions.

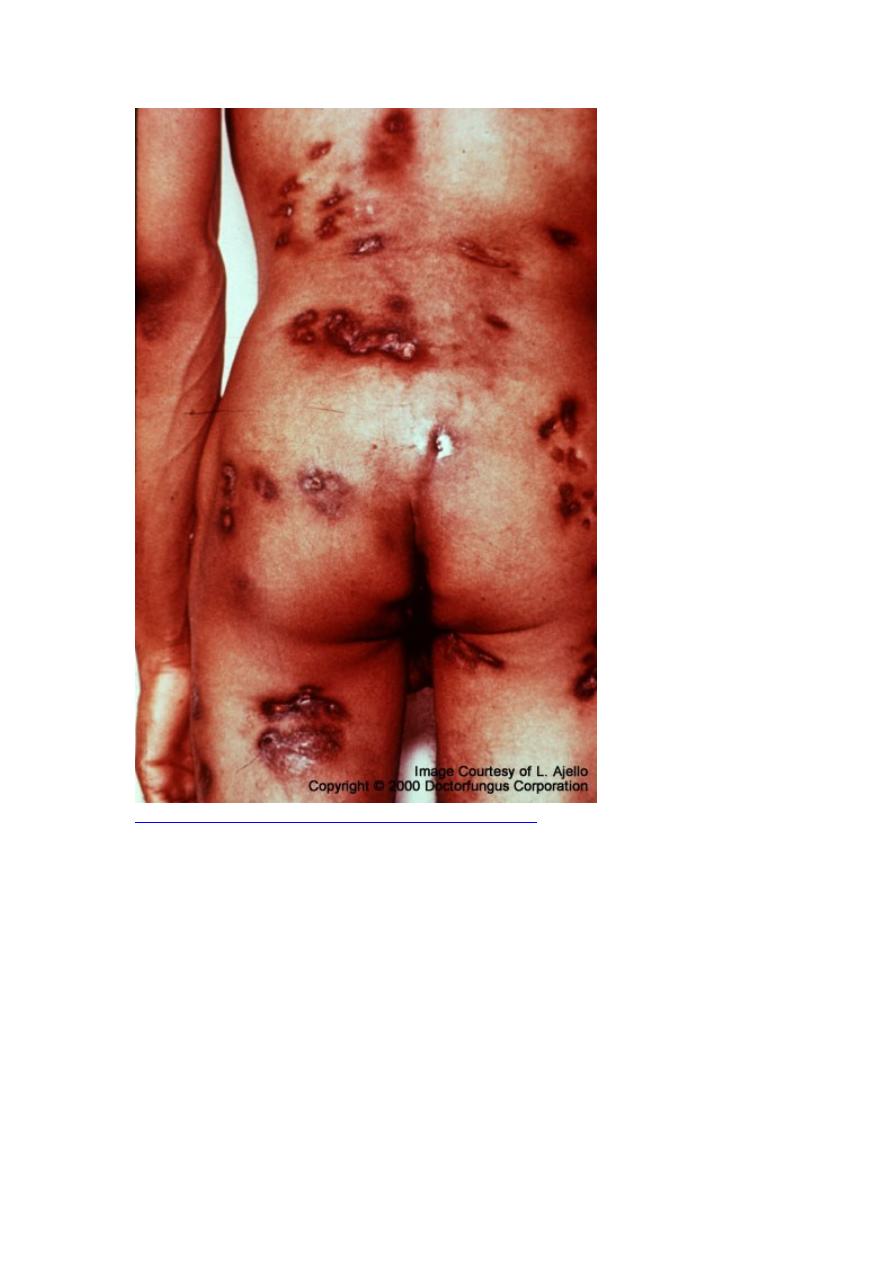

Sometimes disease progresses, with widespread lung involvement, systemic

dissemination, or both; focal lesions may form in almost any tissue, most commonly

in skin, subcutaneous tissues, bones (osteomyelitis), and meninges (meningitis).

Progressive coccidioidomycosis is uncommon in otherwise healthy people and more

likely to occur in the following contexts:

HIV infection

Use of immunosuppressants

Advanced age

2nd half of pregnancy or postpartum

Certain ethnic backgrounds (Filipino, African American, Native American,

Hispanic, and Asian, in decreasing order of relative risk)

Symptoms and Signs

Primary coccidioidomycosis

Most patients are asymptomatic, but nonspecific respiratory symptoms resembling

those of influenza, acute bronchitis, or, less often, acute pneumonia or pleural effusion

sometimes occur. Symptoms, in decreasing order of frequency, include fever, cough,

chest pain, chills, sputum production, sore throat, and hemoptysis.

Physical signs may be absent or limited to scattered rales with or without areas of

dullness to percussion over lung fields. Some patients develop hypersensitivity to the

localized respiratory infection, manifested by arthritis, conjunctivitis, erythema

nodosum, or erythema multiforme.

Primary pulmonary lesions sometimes leave nodular coin lesions that must be

distinguished from tumors, TB, and other granulomatous infections. Sometimes

residual cavitary lesions develop; they may vary in size over time and often appear

thin-walled. A small percentage of these cavities fail to close spontaneously.

Hemoptysis or the threat of rupture into the pleural space occasionally necessitates

surgery.

Progressive coccidioidomycosis

Nonspecific symptoms develop a few weeks, months, or occasionally years after

primary infection; they include low-grade fever, anorexia, weight loss, and weakness.

Extensive pulmonary involvement is uncommon in otherwise healthy people and

occurs mainly in those who are immunocompromised. It may cause progressive

cyanosis, dyspnea, and mucopurulent or bloody sputum.

Symptoms of extrapulmonary lesions depend on the site. Draining sinus tracts

sometimes connect deeper lesions to the skin. Localized extrapulmonary lesions often

become chronic and recur frequently, sometimes long after completion of seemingly

successful antifungal therapy.

Coccidioidomycosis—Disseminated (Multiple Lesions)

Untreated disseminated coccidioidomycosis is usually fatal and, if meningitis is

present, is uniformly fatal without prolonged and possibly lifelong treatment.

Mortality rates in patients with advanced HIV infection exceed 70% within 1 mo of

diagnosis; whether treatment can alter mortality rates is unclear.

Diagnosis

Cultures (routine or fungal)

Microscopic examination of specimens to check for C. immitis spherules

Serologic testing

Eosinophilia may be an important clue in identifying coccidioidomycosis. The

diagnosis is suspected based on history and typical physical findings, when apparent;

chest x-ray findings can help confirm the diagnosis, which can be established by

fungal culture or by visualization of C. immitis spherules in sputum, pleural fluid,

CSF, exudate from draining lesions, or biopsy specimens. Intact spherules are usually

20 to 80 μm in diameter, thick-walled, and filled with small (2 to 4 μm) endospores.

Endospores released into tissues from ruptured spherules may be mistaken for

nonbudding yeasts. Because culturing Coccidioides can pose a severe biohazard to

laboratory personnel, the laboratory should be notified of the suspected diagnosis.

Serologic testing for anticoccidioidal antibodies using an immunodiffusion kit (for

IgG and IgM antibodies) and complement fixation (for IgG antibodies) are the most

useful tests. Titers ≥ 1:4 in serum are consistent with current or recent infection, and

high titers (≥ 1:32) signify an increased likelihood of extrapulmonary dissemination.

However, immunocompromised patients may have low titers. Titers should decline

during successful therapy. The presence of complement-fixing antibodies in CSF is

diagnostic of coccidioidal meningitis and is important because CSF cultures are rarely

positive. A urine antigen test that may be useful in cases of pneumonia and

disseminated infection has been developed.

Delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity to coccidioidin or spherulin usually develops

within 10 to 21 days after acute infections in immunocompetent patients but is

characteristically absent in progressive disease. Because this test is positive in most

people in endemic areas, its primary value is for epidemiologic studies rather than for

diagnosis.

Treatment

For mild to moderate disease, fluconazole or itraconazole

For severe disease, amphotericin B

Patients with primary coccidioidomycosis and risk factors for severe or progressive

disease should be treated. Treatment for primary coccidioidomycosis is controversial

in low-risk patients. Some experts give fluconazole because its toxicity is low and

because even in low-risk patients, there is a small risk of hematogenous seeding,

especially to bone or brain. In addition, symptoms resolve more quickly in treated

patients than in those who are not treated with an antifungal. Others think that

fluconazole may blunt the immune response and that risk of hematogenous seeding in

primary infection is too low to warrant use of fluconazole. High complement fixation

titers indicate spread and the need for treatment.

Mild to moderate nonmeningeal extrapulmonary involvement should be treated with

fluconazole ≥ 400 mg po once/day or itraconazole 200 mg po bid. Voriconazole 200

mg po or IV bid or posaconazole 400 mg po bid are alternatives but have not been

well-studied. For severe illness, amphotericin B 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg IV over 2 to 6 h

once/day is given for 4 to 12 wk until total dose reaches 1 to 3 g, depending on degree

of infection. Lipid formulations of amphotericin B are preferred over conventional

amphotericin B. Patients can usually be switched to an oral azole once they have been

stabilized, usually within several weeks.

Patients with HIV- or AIDS-associated coccidioidomycosis require maintenance

therapy to prevent relapse; fluconazole 200 mg po once/day or itraconazole 200 mg

po bid usually is sufficient, given until the CD4 cell count is > 250/μL.

For meningeal coccidioidomycosis, fluconazole is used. The optimal dose is unclear;

oral doses of 800 to 1200 mg once/day may be more effective than 400 mg once/day.

Treatment for meningeal coccidioidomycosis should be given lifelong. Surgical

removal of involved bone may be necessary to cure osteomyelitis.