Antifungal Drugs

Drugs for systemic antifungal treatment include amphotericin B (and its lipid

formulations), various azole derivatives, echinocandins, and flucytosine (see Table:

Some Drugs for Systemic Fungal Infections

). Amphotericin B, an effective but

relatively toxic drug, has long been the mainstay of antifungal therapy for invasive

and serious mycoses. However, newer potent and less toxic triazoles and

echinocandins are now often recommended as first-line drugs for many invasive

fungal infections. These drugs have markedly changed the approach to antifungal

therapy, sometimes even allowing oral treatment of chronic mycoses.

Some Drugs for Systemic Fungal Infections

Drug

Uses

Dose

Some Adverse Effects

Amphotericin

B

Most fungal infections

(Not for

Pseudallescheria sp)

Conventional

(deoxycholate)

formulation: 0.5–

1.0 mg/kg IV

once/day

Conventional formulation:

Acute infusion reactions,

neuropathy, GI upset, renal

failure, anemia,

thrombophlebitis, hearing

.loss, rash, hypokalemia,

hypomagnesemia

Various lipid

formulations: 3–5

mg/kg IV

once/day

Lipid formulations:

Infusion reactions*, renal

failure*

Anidulafungin

Candidiasis, including

candidemia

200 mg IV on day

1, then 100 mg IV

once/day

For esophageal

candidiasis, half

of this dose

Hepatitis, diarrhea,

hypokalemia, infusion

reactions

Caspofungin

Aspergillosis

Candidiasis, including

candidemia

70 mg IV on day

1, then 50 mg IV

once/day

Phlebitis, headache, GI

upset, rash,

Fluconazole

Mucosal and systemic

candidiasis

Cryptococcal

meningitis

Coccidioidal

meningitis

100–800 mg po or

IV once/day

(loading dose may

be given)

Children: 3–12

mg/kg po or IV

once/day

GI upset, hepatitis, QT

prolongation

Flucytosine

Candidiasis (systemic)

Cryptococcosis

12.5–37.5 mg/kg

po qid

Pancytopenia due to bone

marrow toxicity,

neuropathy, nausea,

Drug

Uses

Dose

Some Adverse Effects

vomiting, hepatic and renal

injury, colitis

Itraconazole

Dermatomycosis

Histoplasmosis,

blastomycosis,

coccidioidomycosis,

sporotrichosis

100 mg po

once/day to 200

mg po bid

Hepatitis, GI upset, rash,

headache, dizziness,

hypokalemia,

hypertension, edema, QT

prolongation

Micafungin

Candidiasis, including

candidemia

100 mg IV

once/day (dose

150 mg for

esophageal

candidiasis)

Phlebitis, hepatitis, rash,

headache, nausea

Posaconazole

Prophylaxis for

invasive aspergillosis

and candidiasis

200 mg po tid

Hepatitis, GI upset, rash,

QT prolongation

Oral candidiasis

100 mg po bid on

day 1, then 100

mg once/day for

13 days

Oral candidiasis

refractory to

itraconazole

400 mg po bid

Voriconazole

Invasive aspergillosis

Fusariosis

Scedosporiosis

6 mg/kg IV for 2

loading doses,

then 200 mg po q

12 h

or

3 to 6 mg/kg IV q

12 h

GI upset, transient visual

disturbances, peripheral

edema, rash, hepatitis, QT

prolongation

*This adverse effect is less common with lipid formulations than with the

conventional formulation.

Clinical Calculator: QT Interval Correction (EKG)

Amphotericin B

Amphotericin B has been the mainstay of antifungal therapy for invasive and serious

mycoses, but other antifungals (eg, fluconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, the

echinocandins) are now considered first-line drugs for many of these infections.

Although amphotericin B does not have good CSF penetration, it is still effective for

certain mycoses such as cryptococcal meningitis.

For chronic mycoses , amphotericin B deoxycholate is usually started at ≥ 0.3 mg/kg

IV once/day, increased as tolerated to the desired dose (0.4 to 1.0 mg/kg; generally

not > 50 mg/day); many patients tolerate the target dose on the first day.

For acute, life-threatening mycoses , amphotericin B deoxycholate may be started at

0.6 to 1.0 mg/kg IV once/day.

Formulations

There are 2 formulations of amphotericin:

Deoxycholate (standard)

Lipid-based

The standard formulation , amphotericin B deoxycholate, must always be given in

5% D/W because salts can precipitate the drug. It is usually given over 2 to 3 h,

although more rapid infusions over 20 to 60 min can be used in selected patients.

However, more rapid infusions usually have no advantage. Many patients experience

chills, fever, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, headache, and, occasionally, hypotension

during and for several hours after an infusion. Amphotericin B may also cause

chemical thrombophlebitis when given via peripheral veins; a central venous catheter

may be preferable. Pretreatment with acetaminophen or NSAIDs is often used; if

these drugs are ineffective, hydrocortisone 25 to 50 mg or diphenhydramine 25 mg is

sometimes added to the infusion or given as a separate IV bolus. Often,

hydrocortisone can be tapered and omitted during extended therapy. Severe chills and

rigors can be relieved or prevented by meperidine 50 to 75 mg IV.

Several lipid vehicles reduce the toxicity of amphotericin B (particularly

nephrotoxicity and infusion-related symptoms). Two preparations are available:

Amphotericin B lipid complex

Liposomal amphotericin B

Lipid formulations are preferred over conventional amphotericin B because they

cause fewer infusion-related symptoms and less nephrotoxicity.

Adverse effects

The main adverse effects are

Nephrotoxicity (most common)

Hypokalemia

Hypomagnesemia

Bone marrow suppression

Renal impairment is the major toxic risk of amphotericin B therapy. Serum creatinine

and BUN should be monitored before treatment and at regular intervals during

treatment: several times/wk for the first 2 to 3 wk, then 1 to 4 times/mo as clinically

indicated. Amphotericin B is unique among nephrotoxic antimicrobial drugs because

it is not eliminated appreciably via the kidneys and does not accumulate as renal

failure worsens. Nevertheless, dosages should be lowered, or a lipid formulation

should be used instead if serum creatinine rises to > 2.0 to 2.5 mg/dL (> 177 to 221

μmol/L) or BUN rises to > 50 mg/dL (> 18 mmol urea/L). Acute nephrotoxicity can

be reduced by aggressive IV hydration with saline before amphotericin B infusion; at

least 1 L of normal saline should be given before amphotericin infusion. Mild to

moderate renal function abnormalities induced by amphotericin B usually resolve

gradually after therapy is completed. Permanent damage occurs primarily after

prolonged treatment; after > 4 g total dose, about 75% of patients have persistent renal

insufficiency.

Amphotericin B also frequently suppresses bone marrow function, manifested

primarily by anemia. Hepatotoxicity or other untoward effects are unusual.

Azole Antifungals

Azoles block the synthesis of ergosterol, an important component of the fungal

cell membrane. They can be given orally to treat chronic mycoses. The first such

oral drug, ketoconazole, has been supplanted by more effective, less toxic triazole

derivatives, such as fluconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole.

Drug interactions can occur with all azoles but are less likely with fluconazole.

The drug interactions mentioned below are not intended as a complete listing;

clinicians should r

Fluconazole

This water-soluble drug is absorbed almost completely after an oral dose. It is

excreted largely unchanged in urine and has a half-life of > 24 h, allowing single daily

doses. It has high penetration into CSF (≥ 70% of serum levels) and has been

especially useful in treating cryptococcal and coccidioidal meningitis. It is also one of

the first-line drugs for treatment of candidemia in nonneutropenic patients. Doses

range from 200 to 400 mg po once/day to as high as 800 mg once/day in some

seriously ill patients and in patients infected with Candida glabrata or other Candida

sp (not C. albicans or C. krusei); daily doses of ≥ 1000 mg have been given and had

acceptable toxicity.

Adverse effects that occur most commonly are GI discomfort and rash. More severe

toxicity is unusual, but the following have occurred: hepatic necrosis, Stevens-

Johnson syndrome, anaphylaxis, alopecia, and, when taken for long periods of time

during the 1st trimester of pregnancy, congenital fetal anomalies.

Drug interactions occur less often with fluconazole than with other azoles. However,

fluconazole sometimes elevates serum levels of Ca channel blockers, cyclosporine,

rifabutin, phenytoin, tacrolimus, warfarin-type oral anticoagulants, sulfonylurea drugs

(eg, tolbutamide), and zidovudine. Rifampin may lower fluconazole blood levels.

Itraconazole

This drug has become the standard treatment for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis as

well as for mild or moderately severe histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and

paracoccidioidomycosis. It is also effective in mild cases of invasive aspergillosis,

some cases of coccidioidomycosis, and certain types of chromoblastomycosis.

Despite poor CSF penetration, itraconazole can be used to treat some types of fungal

meningitis, but it is not the drug of choice. Because of its high lipid solubility and

protein binding, itraconazole blood levels tend to be low, but tissue levels are

typically high. Drug levels are negligible in urine and CSF. Use of itraconazole has

declined as use of voriconazole and posaconazole has increased.

Adverse effects with doses of up to 400 mg/day most commonly are GI, but a few

men have reported erectile dysfunction, and higher doses may cause hypokalemia,

hypertension, and edema. Other reported adverse effects include allergic rash,

hepatitis, and hallucinations. An FDA black box warning for heart failure has been

issued, particularly with a total daily dose of 400 mg.

Drug and food interactions can be significant. When the capsule form is used, acidic

drinks (eg, cola, acidic fruit juices) or foods (especially high-fat foods) improve

absorption of itraconazole from the GI tract. However, absorption may be reduced if

itraconazole is taken with prescription or OTC drugs used to lower gastric acidity.

Several drugs, including rifampin, rifabutin, didanosine, phenytoin, and

carbamazepine, may decrease serum itraconazole levels. Itraconazole also inhibits

metabolic degradation of other drugs, elevating blood levels with potentially serious

consequences. Serious, even fatal cardiac arrhythmias may occur if itraconazole is

used with cisapride (not available in the US) or some antihistamines (eg, terfenadine,

astemizole, perhaps loratadine). Rhabdomyolysis has been associated with

itraconazole-induced elevations in blood levels of cyclosporine or statins. Blood

levels of some drugs (eg, digoxin, tacrolimus, oral anticoagulants, sulfonylureas) may

increase when these drugs are used with itraconazole.

Posaconazole

The triazole posaconazole is available as an oral suspension and a tablet. An IV

formulation will probably be available soon. This drug is highly active against yeasts

and molds and effectively treats various opportunistic mold infections, such as those

due to dematiaceous (dark-walled) fungi (eg, Cladophialophora sp). It is the only oral

azole effective against many of the species that cause mucormycosis. Posaconazole

can also be used as fungal prophylaxis in neutropenic patients with various cancers

and in bone marrow transplant recipients.

Adverse effects for posaconazole, as for other triazoles, include a prolonged QT

interval and hepatitis.

Drug interactions occur with many drugs, including rifabutin, rifampin, statins,

various immunosuppressants, and barbiturates.

Voriconazole

This broad-spectrum triazole is available as a tablet and an IV formulation. It is

considered the treatment of choice for Aspergillus infections in immunocompetent

and immunocompromised hosts. Voriconazole can also be used to treat Scedosporium

apiospermum and Fusarium infections. Additionally, the drug is effective in candidal

esophagitis and invasive candidiasis, although it is not usually considered a first-line

treatment; it has activity against a broader spectrum of Candida sp than does

fluconazole.

Adverse effects that must be monitored for include hepatotoxicity, visual

disturbances (common), hallucinations, and dermatologic reactions. This drug can

prolong the QT interval.

Drug interactions are numerous, notably with certain immunosuppressants used after

organ transplantation.

Echinocandins

Echinocandins are water-soluble lipopeptides that inhibit glucan synthase. They are

available only for IV administration. Their mechanism of action is unique among

antifungal drugs; echinocandins target the fungal cell wall, making them attractive

because they lack cross-resistance with other drugs and their target is fungal and has

no mammalian counterpart. Drug levels in urine and CSF are not significant.

Echinocandins available in the US are anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin.

There is little evidence to suggest that one is better than the other, but anidulafungin

appears to interact with fewer drugs than the other two.

These drugs are potently fungicidal against most clinically important Candida sp but

are considered fungistatic against Aspergillus.

Adverse effects include hepatitis and rash.

Flucytosine

Flucytosine, a nucleic acid analog, is water soluble and well-absorbed after oral

administration. Preexisting or emerging resistance is common, so it is almost always

used with another antifungal, usually amphotericin B. Flucytosine plus amphotericin

B is used primarily to treat cryptococcosis but is also valuable for some cases of

disseminated candidiasis (including endocarditis), other yeast infections, and severe

invasive aspergillosis. Flucytosine plus antifungal azoles may be beneficial in treating

cryptococcal meningitis and some other mycoses.

The usual dose (12.5 to 37.5 mg/kg po qid) leads to high drug levels in serum, urine,

and CSF.

Major adverse effects are bone marrow suppression (thrombocytopenia and

leukopenia), hepatotoxicity, and enterocolitis; only degree of bone marrow

suppression is proportional to serum levels.

Because flucytosine is cleared primarily by the kidneys, blood levels rise if

nephrotoxicity develops during concomitant use with amphotericin B, particularly

when amphotericin B is used in doses > 0.4 mg/kg/day. Flucytosine serum levels

should be monitored, and the dosage should be adjusted to keep levels between 40

and 90 μg/mL. CBC and renal and liver function tests should be done twice/wk. If

blood levels are unavailable, therapy is begun at 25 mg/kg qid, and dosage is

decreased if renal function deteriorates.

efer to a specific drug interaction reference before using azole antifungal drugs.

Blastomycosis

lastomycosis is a pulmonary disease caused by inhaling spores of the dimorphic

fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis; occasionally, the fungi spread hematogenously,

causing extrapulmonary disease. Symptoms result from pneumonia or from

dissemination to multiple organs, most commonly the skin. Diagnosis is clinical, by

chest x-ray, or both and is confirmed by laboratory identification of the fungi.

Treatment is with itraconazole, fluconazole, or amphotericin B.

(See also the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s

management of patients with blastomycosis

In North America, the endemic area for blastomycosis includes

Ohio–Mississippi River valleys (extending into the middle Atlantic and

southeastern states)

Northern Midwest

Upstate New York

Southern Canada

Rarely, the infection occurs in the Middle East and Africa.

Immunocompetent people can contract this infection. Although blastomycosis may be

more common and more severe in immunocompromised patients, it is a less common

opportunistic infection than histoplasmosis or coccidioidomycosis.

B. dermatitidis grows as a mold at room temperature in soil enriched with animal

excreta and in moist, decaying, acidic organic material, often near rivers. In the lungs,

inhaled spores convert into large (15 to 20 μm) invasive yeasts, which form

characteristic broad-based buds.

Once in the lungs, infection may

Remain localized in the lungs

Disseminate hematogenously

Hematogenous dissemination can cause focal infection in numerous organs, including

the skin, prostate, epididymides, testes, kidneys, vertebrae, ends of long bones,

subcutaneous tissues, brain, oral or nasal mucosa, thyroid, lymph nodes, and bone

marrow.

Symptoms and Signs

Pulmonary

Pulmonary blastomycosis may be asymptomatic or cause an acute, self-limited

disease that often goes unrecognized. It can also begin insidiously and develop into a

chronic, progressive infection. Symptoms include a productive or dry hacking cough,

chest pain, dyspnea, fever, chills, and drenching sweats.

Pleural effusion occurs occasionally. Some patients have rapidly progressive

infections, and acute respiratory distress syndrome may develop.

Extrapulmonary

In extrapulmonary disseminated blastomycosis, symptoms depend on the organ

involved.

Skin lesions are by far the most common; they may be single or multiple and may

occur with or without clinically apparent pulmonary involvement. Papules or

papulopustules usually appear on exposed surfaces and spread slowly. Painless

miliary abscesses, varying from pinpoint to 1 mm in diameter, develop on the

advancing borders. Irregular, wartlike papillae may form on surfaces. Sometimes

bullae develop. As lesions enlarge, the centers heal, forming atrophic scars. When

fully developed, an individual lesion appears as an elevated verrucous patch, usually ≥

2 cm wide with an abruptly sloping, purplish red, abscess-studded border. Ulceration

may occur if bacterial superinfection is present.

If bone lesions develop, overlying areas are sometimes swollen, warm, and tender.

Genital lesions cause painful epididymal swelling, deep perineal discomfort, or

prostatic tenderness detected during rectal examination.

CNS involvement can manifest as brain abscess, epidural abscess, or meningitis.

Diagnosis

Fungal cultures and smear

Blastomyces urine antigen

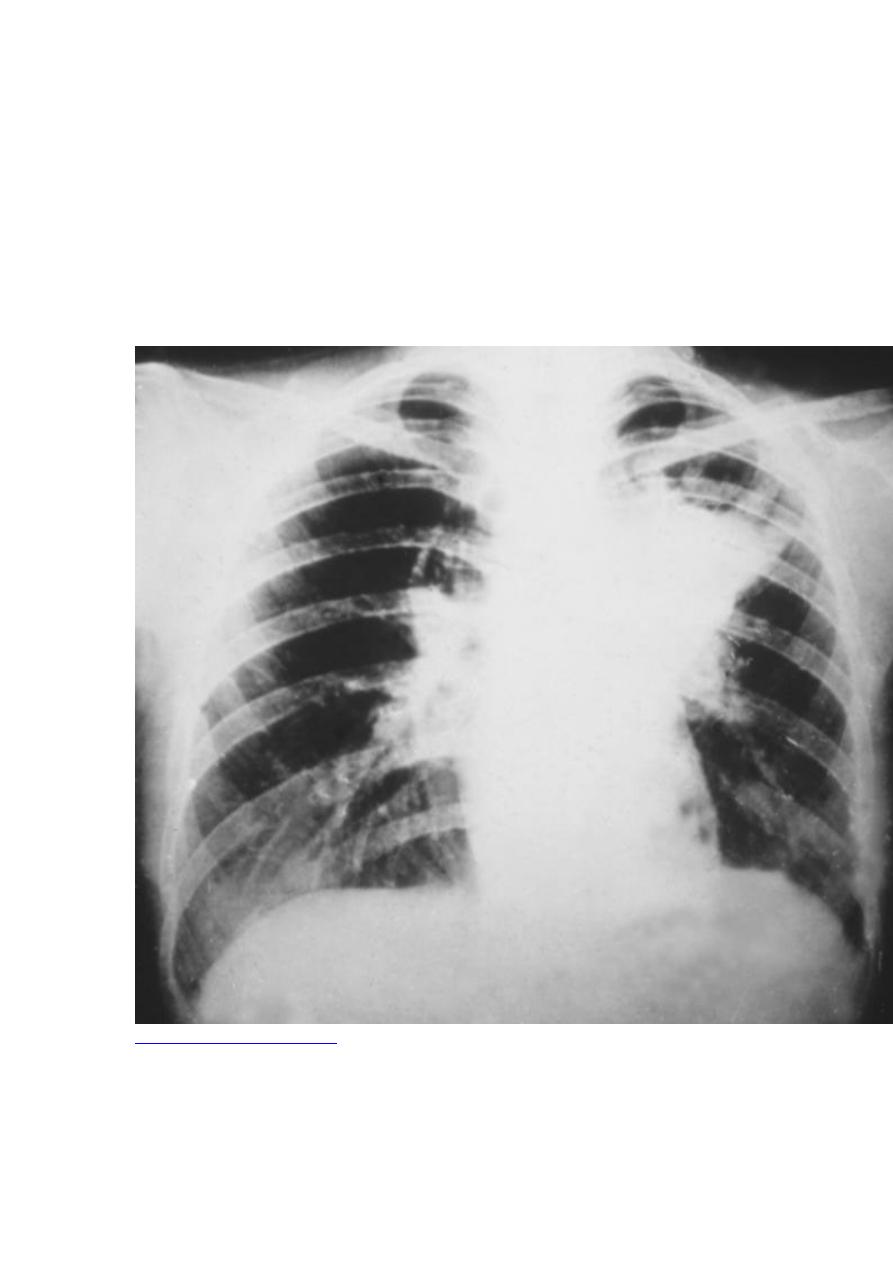

A chest x-ray should be taken. Focal or diffuse infiltrates may be present, sometimes

as patchy bronchopneumonia fanning out from the hilum. These findings must be

distinguished from other causes of pneumonia (eg, other mycoses, TB, tumors). Skin

lesions can be mistaken for sporotrichosis, TB, iodism, or basal cell carcinoma.

Genital involvement may mimic TB.

Cultures of infected material are done; they are definitive when positive. Because

culturing Blastomyces can pose a severe biohazard to laboratory personnel, the

laboratory should be notified of the suspected diagnosis. The organism’s

characteristic appearance, seen during microscopic examination of tissues or sputum,

is also frequently diagnostic. Serologic testing is not sensitive but is useful if positive.

A urine antigen test is useful, but cross-reactivity with Histoplasma is high.

Treatment

For mild to moderate disease, itraconazole

For severe, life-threatening infection, amphotericin B

Untreated blastomycosis is usually slowly progressive and is rarely ultimately fatal.

Treatment depends on severity of the infection. For mild to moderate disease,

itraconazole 200 mg po tid for 3 days, followed by 200 mg po once/day or bid for 6 to

12 mo is used. Fluconazole appears less effective, but 400 to 800 mg po once/day

may be tried in itraconazole-intolerant patients with mild disease. For severe, life-

threatening infections, IV amphotericin B is usually effective; therapy is changed to

itraconazole once patients improve.

Voriconazole and posaconazole are highly active against B. dermatitidis, but their role

has not yet been defined.

Key Points

Inhaling spores of the dimorphic fungus Blastomyces can cause pulmonary

disease and, less commonly, disseminated infection (particularly to the skin).

In North America, blastomycosis is endemic in the regions around the Great

Lakes and in the mid-Atlantic and Southeast.

Diagnose using cultures of infected material; serologic testing is specific but

not very sensitive.

For mild to moderate disease, use itraconazole.

For severe disease, use amphotericin B.

Candidiasis (Invasive)

(Candidosis; Moniliasis)

Candidiasis is infection by Candida sp (most often C. albicans), manifested by

mucocutaneous lesions, fungemia, and sometimes focal infection of multiple sites.

Symptoms depend on the site of infection and include dysphagia, skin and mucosal

lesions, blindness, vaginal symptoms (itching, burning, discharge), fever, shock,

oliguria, renal shutdown, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Diagnosis is

confirmed by histopathology and cultures from normally sterile sites. Treatment is

with amphotericin B, fluconazole, echinocandins, voriconazole, or posaconazole.

(See also the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s

Candida sp are commensal organisms that inhabit the GI tract and sometimes the skin

(see

Candidiasis (Mucocutaneous) : Etiology

). Unlike other systemic mycoses,

candidiasis results from endogenous organisms. Most infections are caused by C.

albicans; however, C. glabrata (formerly Torulopsis glabrata) and other non-albicans

species are increasingly involved in fungemia, UTIs, and, occasionally, other focal

disease. C. glabrata is frequently less susceptible to fluconazole than other species; C.

kruseiis inherently resistant.

Candida sp account for about 80% of major systemic fungal infections and are the

most common cause of fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. Candidal

infections are one of the most common hospital-acquired infections.

Candidiasis involving the mouth and esophagus is a defining opportunistic infection

in AIDS. Although mucocutaneous candidiasis is frequently present in HIV-infected

patients, hematogenous dissemination is unusual unless other specific risk factors are

present (see below). Neutropenic patients (eg, those receiving cancer chemotherapy)

are at high risk of developing life-threatening disseminated candidiasis.

Candidemia may occur in nonneutropenic patients during prolonged hospitalization.

This bloodstream infection is often related to one or more of the following:

Central venous catheters

Major surgery

Broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy

IV hyperalimentation

IV lines and the GI tract are the usual portals of entry. Candidemia often prolongs

hospitalization and increases mortality due to concurrent disorders. Prolonged or

untreated candidemia may lead to endocarditis or meningitis as well as to focal

involvement of skin, subcutaneous tissues, bones, joints, liver, spleen, kidneys, eyes,

and other tissues. Endocarditis is commonly related to IV drug abuse, valve

replacement, or intravascular trauma induced by indwelling IV catheters.

All forms of disseminated candidiasis should be considered serious, progressive, and

potentially fatal.

Symptoms and Signs

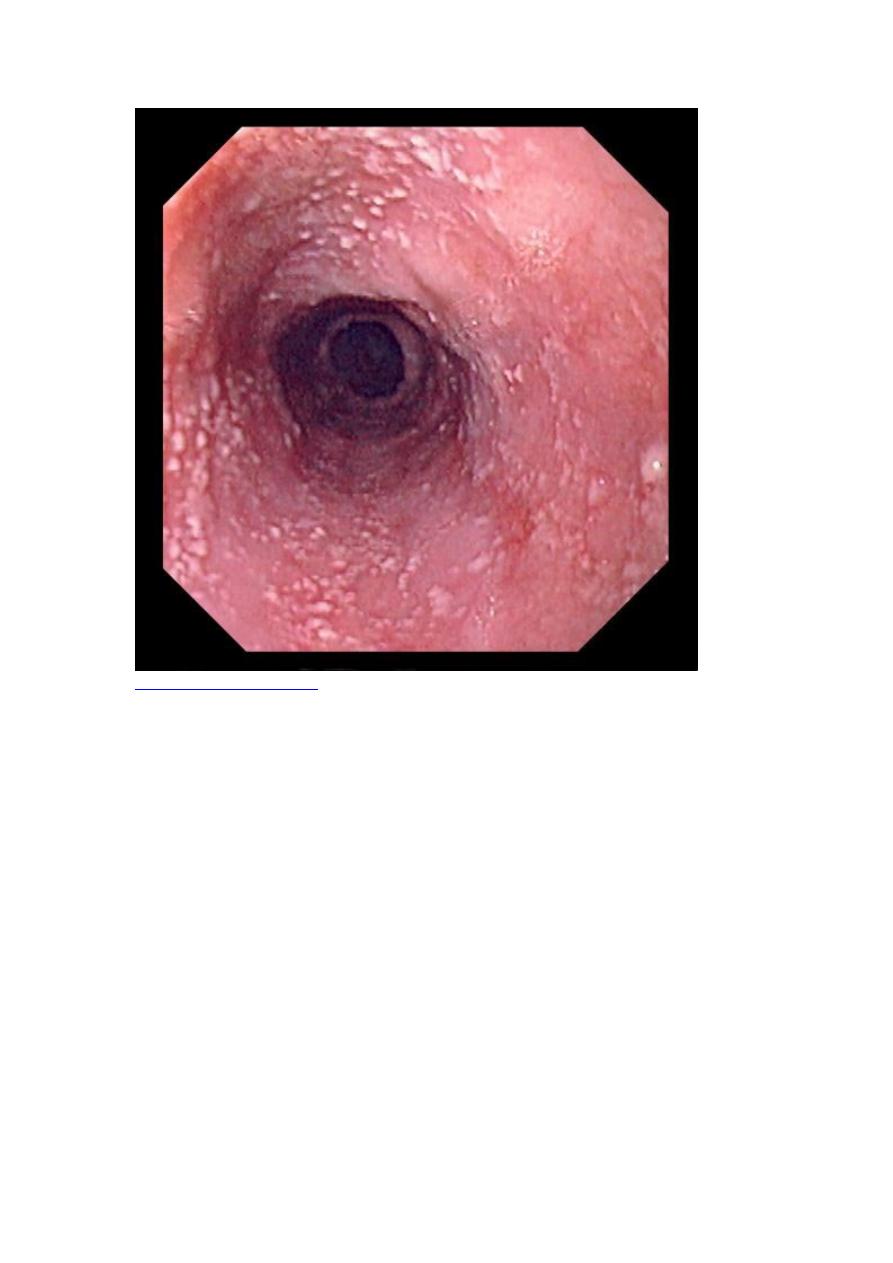

Esophageal candidiasis is most often manifested by dysphagia.

Candidemia usually causes fever, but no symptoms are specific. Some patients

develop a syndrome resembling bacterial sepsis, with a fulminating course that may

include shock, oliguria, renal shutdown, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Candidal endophthalmitis starts as white retinal lesions that are initially asymptomatic

but can progress, opacifying the vitreous and causing potentially irreversible scarring

and blindness. In neutropenic patients, retinal hemorrhages occasionally also occur,

but actual infection of the eye is rare.

Papulonodular skin lesions may also develop, especially in neutropenic patients, in

whom they indicate widespread hematogenous dissemination to other organs.

Symptoms of other focal infection depend on the organ involved.

Diagnosis

Histopathology and fungal cultures

Blood cultures

Serum β-glucan testing

Because Candida spp are commensal, their culture from sputum, the mouth, the

vagina, urine, stool, or skin does not necessarily signify an invasive, progressive

infection. A characteristic clinical lesion must also be present, histopathologic

evidence of tissue invasion (eg, yeasts, pseudohyphae, or hyphae in tissue specimens)

must be documented, and other etiologies must be excluded. Positive cultures of

specimens taken from normally sterile sites, such as blood, CSF, pericardium,

pericardial fluid, or biopsied tissue, provide definitive evidence that systemic therapy

is needed.

Serum β-glucan is often positive in patients with invasive candidiasis; conversely, a

negative result indicates low likelihood of systemic infection.

Ophthalmologic examination to check for endophthalmitis is recommended for all

patients with candidemia.

Treatment

An echinocandin if patients are severely or critically ill or if infection with C.

glabrata or C. krusei is suspected

Fluconazole if patients are clinically stable or if infection with C. albicans or

C. parapsilosis is suspected

Alternatively, voriconazole or amphotericin B

In patients with invasive candidiasis, predisposing conditions (eg, neutropenia,

immunosuppression, use of broad-spectrum antibacterial antibiotics,

hyperalimentation, presence of indwelling lines) should be reversed or controlled if

possible. In nonneutropenic patients, IV catheters should be removed.

When an echinocandin is indicated (if patients are moderately severely ill or critically

ill [most neutropenic patients] or if C. glabrata or C. krusei is suspected), one of the

following drugs can be used: caspofungin, loading dose 70 mg IV, then 50 mg IV

once/day; micafungin 100 mg IV once/day; or anidulafungin, loading dose 200 mg

IV, then 100 mg IV once/day.

If fluconazole is indicated (if patients are clinically stable or if C. albicans or C.

parapsilosis is suspected), loading dose is 800 mg (12 mg/kg) po or IV once, followed

by 400 mg (6 mg/kg) once/day.

Treatment is continued for 14 days after the last negative blood culture.

Esophageal candidiasis is treated with fluconazole 200 to 400 mg po or IV once/day

or itraconazole 200 mg po once/day. If these drugs are ineffective or if infection is

severe, voriconazole 4 mg/kg po or IV bid, posaconazole 400 mg po bid, or one of the

echinocandins may be used. Treatment is continued for 14 to 21 days.