_

In health

Visceral lubrication Fluid and particulate absorption

_

In disease

Pain perception (mainly parietal) Inflammatory and immune responses

Fibrinolytic activity

PERITONITIS

Peritonitis is simply defined as inflammation of the peritoneum and may be

localized or generalised. Most cases of peritonitis are caused by an invasion

of the peritoneal cavity by bacteria, , acute bacterial peritonitis. In this

instance, free fluid spills into the peritoneal cavity and circulates largely

directed by the normal peritoneal attachments and gravity.

For example, spillage from a perforated peptic ulcer may run down the right

paracolic gutter leading to presentation with pain in the right iliac fossa

(Valentino’s syndrome) .

Even in patients with non-bacterial peritonitis (e.g. acute pancreatitis,

intraperitoneal rupture of the bladder or haemoperitoneum), the peritoneum

often becomes infected by transmural spread of organisms from the bowel.

Such translocation is a feature of the systemic inflammatory response on the

bowel .Most duodenal and gastric perforations are initially sterile for up to

several hours before becoming secondarily infected

Paths to peritoneal infection

_

Gastrointestinal perforation, e.g. perforated ulcer, appendix, diverticulum

_

Transmural translocation (no perforation), e.g. pancreatitis, ischaemic bowel

_

Exogenous contamination, e.g. drains, open surgery, trauma

_

Female genital tract infection, e.g. pelvic inflammatory disease

_

Haematogenous spread (rare), e.g. septicaemia

Microbiology

Bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract

The number of bacteria within the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract is normally

low until the distal small bowel is reached. However, disease leading to stasis and

overgrowth (e.g. obstruction, chronic and acute motility disturbances) may

increase proximal colonisation. The biliary and pancreatic tracts are also

normally free from bacteria, although they may be infected in disease, e.g.

gallstones. Peritoneal infection is usually caused by two or more bacterial strains.

Gram-negative bacteria contain

endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides) in their cell walls that have multiple toxic effects

on the host, primarily by causing the release of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) from

host leukocytes.

Systemic absorption of endotoxin may produce endotoxic shock with hypotension

and impaired tissue perfusion. Other bacteria such as Clostridium welchii produce

harmful exotoxins.

Bacteroides are commonly found in peritonitis. These Gram negative, non-

sporing organisms.

These organisms are resistant to penicillin and streptomycin but sensitive to

metronidazole, clindamycin

-

Microorganisms in peritonitis

Gastrointestinal source

_

Escherichia coli

Streptococci

Bacteroides

Clostridium Klebsiella pneumoniae

Other sources

_

Chlamydia trachomatis

_

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

_

Haemolytic streptococci

_

Staphylococcu

_

Streptococcus pneumonia

_

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other

spp.

_

Fungal infections

Localised peritonitis

Anatomical and pathological factors may favour the

localization of peritonitis.

Anatomical

The greater sac of the peritoneum is divided into (1) the subphrenicspaces, (2) the

pelvis and (3) the peritoneal cavity proper. The last is divided into a supracolic

and an infracolic compartment by the transverse colon and transverse mesocolon,

which deters the spread of infection from one to the other.

When the supracolic compartment overflows, as is often the case when a peptic

ulcer perforates, it does so over the colon into the infracolic compartment or by

way of the right paracolic gutter to the right iliac fossa and hence to the pelvis.

Pathological

The clinical course is determined in part by the manner in

which

adhesions form around the affected organ. Inflamed peritoneum

loses its

glistening appearance and becomes reddened

and velvety. Flakes of fibrin appear and cause loops of intestine to become

adherent to one another and to the parietes. There is an outpouring of serous

inflammatory exudate rich in leukocytes

and plasma proteins that soon becomes turbid; if localization occurs, the turbid

fluid becomes frank pus. Peristalsis is retarded

.

The greater omentum, by enveloping and becoming adherent to inflamed

structures, often forms a substantial barrier to the spread of infection .

Diffuse (generalised) peritonitis

A number of factors may favour the development of diffuse peritonitis:

•

Speed of peritoneal contamination is a prime factor. If an inflamed appendix or

other hollow viscus perforates before localisation has taken place, there will be an

efflux of contents into the peritoneal cavity, which may spread over a large area

almost instantaneously -Perforation proximal to an obstruction or from sudden

anastomotic separation is associated with severe generalised peritonitis and a high

mortality rate.

•

Stimulation of peristalsis by the ingestion of food or even water hinders

localisation. Violent peristalsis occasioned by the administration of a purgative or

an enema may cause the widespread distribution of an infection that would

otherwise have remained localised.

•

The virulence of the infecting organism may be so great as to render the

localisation of infection difficult or impossible.

•

Young children have a small omentum, which is less effective in localising

infection.

•

Disruption of localised collections may occur with injudicious handling, e.g.

appendix mass or pericolic abscess.

•

Deficient natural resistance (‘immune deficiency’) may result from use of drugs

(e.g. steroids), disease (e.g. acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)) or old

age.

With appropriate treatment, localised peritonitis usually resolves; in about 20 per

cent of cases, an abscess follows. Infrequently, localised peritonitis becomes

diffuse. Conversely, in favourable circumstances, diffuse peritonitis can become

localised, most frequently in the pelvis or at multiple sites within the abdominal

cavity.

Clinical features

Localised peritonitis

The initial symptoms and signs of localised peritonitis

are

those of the underlying condition – usually visceral inflammation (hence

abdominal pain, specific GI symptoms + malaise, anorexia and nausea).

When the peritoneum becomes inflamed, abdominal pain will worsen and,

in general, temperature and pulse rate will rise. The pathognomonic signs

are localized guarding (involuntary abdominal wall contraction to protect

the viscus from the examining hand), a positive ‘release’ sign (rebound

tenderness) and, sometimes, rigidity (involuntary constant contraction of the

abdominal wall over the inflamed parietes).

If inflammation arises under the diaphragm, shoulder tip (‘phrenic’) pain

may be felt as the pain is referred to the C5 dermatome.

In cases of pelvic peritonitis arising from an inflamed appendix in the pelvic

position or from salpingitis, the abdominal signs are often slight; there may

be deep tenderness of one or both lower quadrants alone, but a rectal or

vaginal examination reveals marked tenderness of the pelvic peritoneum.

Diffuse (generalised) peritonitis

Early

Abdominal pain is severe and made worse by moving or breathing. It is first

experienced at the site of the original lesion and spreads outwards from this point.

The patient usually lies still. Tenderness and generalised guarding are found on

palpation when the peritonitis affects the anterior abdominal wall.

Infrequent bowel sounds may still be heard for a few hours but they cease with the

onset of paralytic ileus. Pulse and temperature rise in accord with degree of

inflammation and infection.

Late

If resolution or localisation of generalised peritonitis does not occur, the abdomen

will become rigid (generalised rigidity). Distension is common and bowel sounds

are absent. Circulatory failure ensues, with cold, clammy extremities, sunken eyes,

dry tongue, thready (irregular) pulse and drawn and anxious face

(Hippocratic facies). The patient finally lapses into unconsciousness.

Diagnostic aids

Investigations may elucidate a doubtful diagnosis, but the importance of a

careful history and repeated examination must not be forgotten

.

Bedside

•

Urine dipstix for urinary tract infection

•

ECG if diagnostic doubt (as a cause of

abdominal pain) or cardiac history

.

Bloods

•

Baseline U&E for treatment

•

Full blood count for white cell count

(WCC)

•

Serum amylase estimation may establish the diagnosis of acute

pancreatitis provided that it is remembered that moderately raised

values are frequently found following other abdominal catastrophes

and operations, e.g. perforated duodenal ulcer

.

Imaging

•

Erect chest radiograph to demonstrate free subdiaphramatic gas

•

A supine radiograph of the abdomen may confirm the presence of

dilated gas-filled loops of bowel (consistent with a paralytic ileus),

occasionally show other gas-filled structures that may aid diagnosis,

e.g. biliary tree; the faecal pattern may act as a guide to colonic disease

(absent in sites of

significant inflammation, e.g. diverticulitis). In the patient who is too

ill for an ‘erect’ film, a lateral decubitus film can show gas beneath the

abdominal wall (if CT unavailable).

•

Multiplanar computed tomography (CT) is to identify the cause of peritonitis and

may also influence management decisions, e.g. surgical strategy.

•

Ultrasound scanning has undoubted value in certain situations such as pelvic

peritonitis in females and localized right upper quadrant peritonism.

Invasive

•

peritoneal diagnostic aspiration has little residual value.

Management : General care of the patient

., patients will require some or all of the following

Correction of fluid loss and circulating volume

Patients are frequently hypovolaemic with electrolyte disturbances. The

plasma volume must be restored and electrolyte concentrations corrected.

pre-existent and ongoing fluid losses corrected. Special measures may be

needed for cardiac, pulmonary and renal support, especially if septic shock

is present, including central venous pressure monitoring in patients with

concurrent disease.

Urinary catheterisation ± gastrointestinal decompression

A urinary catheter will give a guide to central perfusion and will be required if

abdominal surgery is to proceed. A nasogastric tube is commonly passed to allow

drainage ± aspiration until paralytic ileus has resolved

.

Antibiotic therapy

Administration of parenteral broad-spectrum (aerobic and anaerobic) antibiotics

prevents the multiplication of bacteria and the release of endotoxins

Analgesia

The patient should be nursed in the sitting-up position and must be relieved of pain

before and after operation.

. Freedom from pain allows early mobilization and adequate physiotherapy in the

postoperative period, which helps to prevent basal pulmonary collapse, deep-vein

thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Specific treatment of the cause

While difficult to generalise, in patients where specific treatment has not been

guided by CT scanning, early surgical intervention is to be preferred to a ‘wait

and see’ policy assuming that the patient is fit for anaesthesia and that

resuscitation has resulted in a satisfactory restitution of normal body physiology.

This rule is particularly true for previously healthy patients and those with

postoperative peritonitis. More caution is, of course, required in patients at high

operative risk because of comorbidity or advanced age.

_

Complications of peritonitis

_

Systemic complications

Bacteraemic/endotoxic shock

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Multiorgan dysfunction syndrome

Death

_

Abdominal complications

Paralytic ileus

Residual or recurrent abscess/inflammatory mass

Portal pyaemia/liver abscess

Adhesional small bowel obstruction

This rule is particularly true for previously healthy patients and those with

postoperative peritonitis. More caution is, of course, required in patients at high

operative risk because of comorbidity or advanced age.

Primary peritonitis

Primary pneumococcal peritonitis may complicate nephrotic syndrome or

cirrhosis in children. Otherwise healthy children, particularly girls between

three and nine years of age, may also be affected, and it is likely that the

route of infection is sometimes via the vagina and Fallopian tubes. At other

times, and

always in males, the infection is blood-borne and secondary to

respiratory tract or middle ear disease.

.

Clinical features

The onset is sudden and the earliest symptom is pain localized to the lower

half of the abdomen. The temperature is raised to 39°C or more and there is

usually frequent vomiting. After 24–48 hours, profuse diarrhoea is

characteristic. There is usually increased frequency of micturition. The last

two symptoms are caused by severe pelvic peritonitis. On examination,

peritonism is usually diffuse but less prominent than in most cases of a

perforated viscus leading to peritonitis.

Investigation and treatment

A leukocytosis _30 000 μL with approximately 90 per cent polymorphs

suggests pneumococcal peritonitis rather than another cause, e.g.

appendicitis. After starting antibiotic therapy and correcting dehydration and

electrolyte imbalance, early surgery is required unless spontaneous infection

of pre-existing ascites is strongly suspected, in which case a diagnostic

peritoneal tap is useful. Laparotomy or laparoscopy may be used. Should the

exudate be odourless and sticky, the diagnosis of pneumococcal

peritonitis is practically certain, but it is essential to perform a

careful exploration to exclude other pathology. Assuming that

no other cause for the peritonitis is discovered, some of the exudate

is aspirated and sent to the laboratory for microscopy, culture

and sensitivity tests. Thorough peritoneal lavage is carried

out and the incision closed. Antibiotic and fluid replacement

therapy are continued and recovery is usual.

Other organisms are now known to cause some cases of primary

peritonitis in children, including Haemophilus, other streptococci

and a few Gram-negative bacteria. Underlying pathology

(including an intravaginal foreign body in girls) must always be

excluded before primary peritonitis can be diagnosed with certainty.

Idiopathic streptococcal and staphylococcal peritonitis

can also occur in adults.

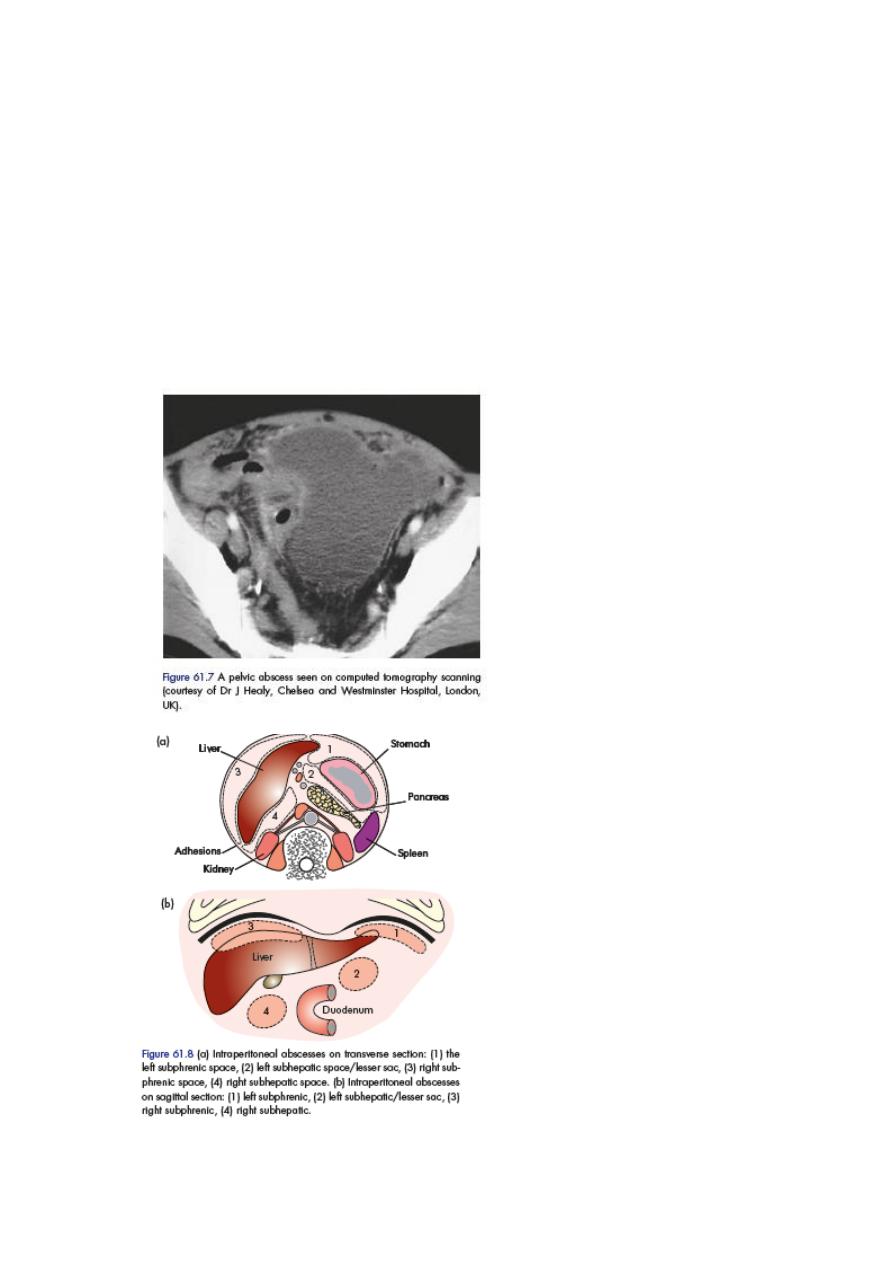

INTRAPERITONEAL ABSCESS

Following intraperitoneal sepsis (usually manifest first as local or diffuse

peritonitis), the anatomy of the peritoneal cavity is such that with the

influence of gravity (depending on patient position – sitting or supine),

abscess development usually occupies one of a number of specific

abdominal or pelvic sites (Figure).

In general, the symptoms and signs of a purulent collection may be vague

and consist of nothing more than lassitude, anorexia and malaise; pyrexia

(often low-grade), mild tachycardia and localised tenderness. Certain sites

have more specific clinical features. Larger abscesses will give rise

to the picture of swinging pyrexia and pulse and a palpable mass.

Blood tests will reveal elevated inflammatory markers

Summary box 61.7

S

Clinical features of an abdominal/pelvic abscess

Symptoms

_

Malaise, lethargy

– failure to recover from surgery as expected

_

Anorexia and weight loss

_

Sweats ± rigors

_

Abdominal/pelvic pain

_

Symptoms from local irritation, e.g. shoulder

tip/hiccoughs

(subphrenic), diarrhoea and mucus (pelvic), nausea and vomiting (any upper

abdominal)

Signs

_

Increased temperature and pulse ± swinging pyrexia

_

Localised abdominal tenderness ± mass (including on pelvic exam

ummary

box 61.9

I

Tuberculous peritonitis

_

Acute (may be clinically indistinguishable from acute

bacterial peritonitis) and chronic forms

_

Abdominal pain, sweats, malaise and weight loss are

frequent

_

Ascites common, may be loculated

_

Caseating peritoneal nodules are common

– distinguish

from metastatic carcinoma and fat necrosis of pancreatitis

_

Intestinal obstruction may respond to antituberculous

treatment without surgery

TUMOURS OF THE PERITONEUM

Primary tumours

Primary tumours of the peritoneum are rare . Mesothelioma of the peritoneum is

less frequent than in the pleural cavity but equally lethal. Asbestos is a recognised

cause. It has a predilection for the pelvic peritoneum.

Chemocytotoxic agents are the mainstay of treatment.

Secondary tumours

Carcinomatosis peritonei

This is a common terminal event in many cases of carcinoma of the stomach,

colon, ovary or other abdominal organs and also of the breast and bronchus. The

peritoneum, both parietal and

visceral, is studded with secondary growths and the peritoneal cavity becomes

filled with clear, straw-coloured or blood-stained ascitic fluid.

The main forms of peritoneal metastases are:

•

discrete nodules – by far the most common variety;

•

plaques varying in size

and colour;

•

diffuse adhesions – this form occurs at a late stage of the disease

and gives rise, sometimes, to a ‘frozen pelvis’.

The main differential diagnosis is from tuberculous peritonitis (tubercles are

greyish and translucent and closely resemble the discrete nodules of peritoneal

carcinomatosis).

Investigation and treatment are as for underlying malignancy.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei

This rare condition occurs more frequently in women. The abdomen is filled with

a yellow jelly, large quantities of which are often encysted. The condition is

associated with mucinous

cystic tumours of the ovary and appendix. Recent studies suggest

that most cases arise from a primary appendiceal tumour with

secondary implantation on to one or both ovaries. It is often

painless and there is frequently no impairment of general

health

, the diagnosis is more often suggested by ultrasound

and CT scanning or made at operation. At laparotomy, masses

of jelly are scooped out. The appendix, if present, should be

excised together with any ovarian tumour.