Presenting Problems In Gastrointestinal Disease

Stomatitis and ‘burning mouth’ sensationStomatitis is inflammation in the mouth from any cause, such as ill-fitting dentures.

Angular stomatitis is inflammation of the corners of the mouth.

The ‘burning mouth syndrome’ consists of a burning sensation with a clinically normal oral mucosa. It occurs more commonly in middle-aged and elderly females. It is probably psychogenic in origin.

Halitosis (bad breath) is a common symptom and is due to poor oral hygiene( anxiety often when halitosis is more apparent to the patient than real) and rarer causes, e.g. oesophageal stricture and pulmonary sepsis.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is defined as difficulty in swallowing. It may coexist with heartburn or vomiting but should be distinguished from both globus sensation (in which anxious people feel a lump in the throat without organic cause) and odynophagia (pain during swallowing, usually from gastro-oesophageal reflux or candidiasis).Dysphagia can occur due to problems in the oropharynx or oesophagus . Oropharyngeal disorders affect the initiation of swallowing at the pharynx and upper oesophageal sphincter. The patient has difficulty initiating swallowing and complains of choking, nasal regurgitation or tracheal aspiration. Drooling ,dysarthria, hoarseness and cranial nerve or other neurological signs may be present. Oesophageal disorders cause dysphagia by obstructing the lumen or by affecting motility. Patients with oesophageal disease complain of food ‘sticking’ after swallowing, although the level at which this is felt correlates poorly with the true site of obstruction. Swallowing of liquids is normal until strictures become extreme.Dyspepsia

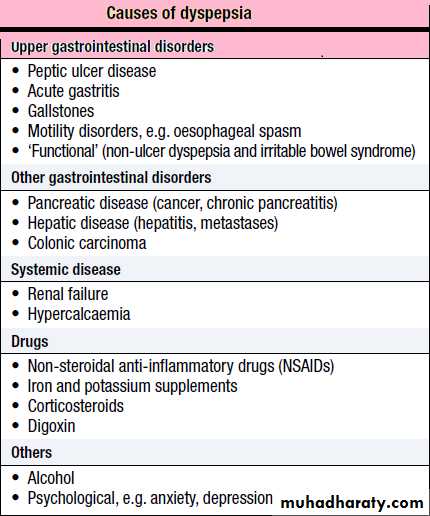

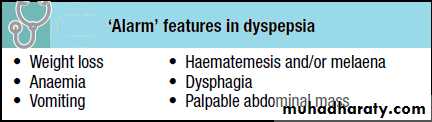

Dyspepsia ‘Indigestion’ is the term used to describe symptoms such as bloating and nausea which are thought to originate from the upper gastrointestinal tract. There are many causes, including some arising outside the digestive system. Heartburn and other ‘reflux’ symptoms are separate Entities . Although symptoms often correlate poorly with the underlying diagnosis, a careful history is important to detect ‘alarm’ features requiring urgent investigation and to detect atypical symptoms which might be due to problems outside the gastrointestinal tract.

Dyspepsia affects up to 80% of the population at some time in life and many patients have no serious underlying disease. Patients who present with new dyspepsia at an age of more than 55 years and younger

patients unresponsive to empirical treatment require investigation to exclude serious disease.

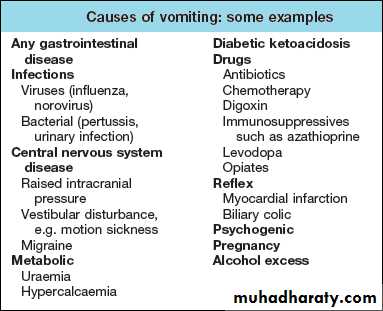

Vomiting

Vomiting is a complex reflex involving both autonomic and somatic neural pathways. Synchronous contraction of the diaphragm, intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles raises intra-abdominal pressure and, combined with relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter, results in forcible ejection of gastric contents. It is important to distinguish true vomiting from regurgitation and to elicit whether the vomiting is acute or chronic (recurrent), as the underlying causes may differ. The majorcauses are shown below.

Nausea is a feeling of wanting to vomit, often associated with autonomic effects including salivation, pallor and sweating.It often precedes actual vomiting. Retching is a strong involuntary unproductive effort to vomit associated with abdominal muscle contraction but without expulsion of

gastric contents through the mouth.

Faeculent vomit suggests low intestinal obstruction or the presence of a gastrocolic fistula.

Haematemesis is vomiting fresh or altered blood (‘coffeegrounds’)

Early-morning nausea and vomiting is seen in pregnancy, alcohol dependence and some metabolic disorders (e.g. uraemia).

Persistent nausea alone is often stress-related and is not due to gastrointestinal disease.

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleedingThe cardinal features are haematemesis the vomiting of blood or altered blood (‘coffeegrounds’) and melaena (the passage of black tarry stools; the black colour due to blood altered by passage through the gut). Melaena can occur with bleeding from any lesion proximal to the right colon. Following a bleed from the upper GI tract, unaltered blood can appear per rectum, but the bleeding must be massive and is almost always accompanied by shock. The passage of dark blood and clots without shock is always due to lower GI bleeding.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding

This may be due to haemorrhage from the colon, anal canal or small bowel. It is useful to distinguish those patients who present with profuse, acute bleeding from those who present with chronic or subacute bleeding of lesser severity.

Patients present with profuse red or maroon diarrhea and with shock.

Subacute or chronic lower gastrointestinal bleeding

This is common at all ages and is usually due to haemorrhoids or anal fissure. Haemorrhoidal bleeding is bright red and occurs during or after defecation. Proctoscopy is used to make the diagnosis but in subjects who also have altered bowel habit and in all patients presenting at over 40 years of age, colonoscopy is necessary to exclude coexisting colorectal cancer. Anal fissure should be suspected when fresh rectal bleeding and anal pain occur during defecation.

Occult gastrointestinal bleeding

In this context occult means that blood or its breakdown products are present in the stool but cannot be seen by the naked eye. Occult bleeding may reach 200 mL per day, cause iron deficiency anaemia and signify serious gastrointestinal disease. Any cause of gastrointestinal bleeding may be responsible but the most important is colorectal cancer, particularly carcinoma of the caecum which may have no gastrointestinal symptoms. In clinical practice, investigation of the gastrointestinal tract

should be considered whenever a patient presents with unexplained iron deficiency anaemia.

Diarrhoea

Gastroenterologists define diarrhoea as the passage of more than 200 g of stool daily, and measurement of stool volume is helpful in confirming this. The most severe symptom in many patients is urgency of defecation, and faecal incontinence is a common event in acute and chronic diarrhoeal illnesses.Simple rules in diarrhoea

A single episode of diarrhoea is commonly due to dietary indiscretion or anxiety.

Large volume watery stools always have an organic cause.

Bloody diarrhoea implies colonic and/or rectal disease.

Acute diarrhoea lasting 2–5 days is most often due to an infective cause.

Acute diarrhoea

This is extremely common and usually due to faecal–oral transmission of bacteria, their toxins, viruses or parasites . Infective diarrhoea is usually shortlived and patients who present with a history of diarrhea lasting more than 10 days rarely have an infective cause. A variety of drugs, including antibiotics, cytotoxic drugs, Proton pump inhibitor (PPIs) and NSAIDs, may be responsible for acute diarrhoea.

Chronic or relapsing diarrhoea

The most common cause is irritable bowel syndrome, which can present with increased frequency of defecation and loose, watery or pellety stools. Diarrhoea rarely occurs at night and is most severe before and after breakfast. At other times the patient is constipated and there are other characteristic symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. The stool often contains mucus but never blood, and 24-hour stool volume is less than 200 g. Chronic diarrhoea can be categorised as disease of the colon or small bowel, or malabsorption . Clinical presentation, examination of the stool, routine blood tests and imaging reveal a diagnosis in many cases. A series of negative investigations usually implies irritable bowel syndrome but some patients clearly have organic disease and need more extensive investigations.

Malabsorption

Diarrhoea and weight loss in patients with a normal diet should always lead to the suspicion of malabsorption.The symptoms are diverse in nature and variable in severity. A few patients have apparently normal bowel habit but diarrhoea is usual and may be watery and voluminous. Bulky, pale and offensive stools which float in the toilet (steatorrhoea) signify fat malabsorption. Abdominal distension, borborygmi, cramps, weight loss and undigested food in the

stool may be present. Some patients complain only of malaise and lethargy. In others, symptoms related to deficiencies of specific vitamins, trace elements and minerals (e.g. calcium, iron, folic acid) may occur .

Anorexia and weight loss

Anorexia describes reduced appetite. It is common in systemic disease and may be seen in psychiatric disorders. Anorexia often accompanies cancer but is usually a late symptom and not of diagnostic help.

Weight loss may be ‘physiological’ due to dieting, exercise, starvation, or the decreased nutritional intake which accompanies old age. Alternatively, weight loss may signify disease and in this case a loss of more than 3 kg over 6 months is significant. Hospital and general practice

weight records may be valuable in confirming that weight loss has occurred, as may reweighing patients at intervals; sometimes weight is regained or stabilises in those with no obvious cause. Pathological weight loss can be due to psychiatric illness, systemic disease, gastrointestinal

causes or advanced disease of many organ system.

Constipation

Constipation is defined as infrequent passage of hard stools. Patients may also complain of straining, a sensation of incomplete evacuation and either perianal or abdominal discomfort. Constipation may be the end result of many gastrointestinal and other medical disorders.

Patients often consider themselves constipated if their bowels are not open on most days, though normal stool frequency is very variable, from 3 times daily to 3 times a week. The difficult passage of hard stool is also regarded as constipation, irrespective of stool frequency. Constipation

with hard stools is rarely due to organic colonic disease.

Abdominal pain

Pain is stimulated mainly by the stretching of smooth muscle or organ capsules. Severe acute abdominal pain can be due to a large number of gastrointestinal conditions, and normally presents as an emergency. An apparent ‘acute abdomen’ can occasionally be due to referred pain from the chest, as in pneumonia or to metabolic causes, such as diabetic ketoacidosis or porphyria.

Check:

Site , intensity, character, duration and frequency of the pain

Aggravating and relieving factors

Associated symptoms, including non-gastrointestinal symptoms.

Upper abdominal pain

Epigastric pain is very common and is often related to food intake. Although functional dyspepsia is the commonest diagnosis, the symptoms of peptic ulcer disease can be identical.

Heartburn (a burning pain behind the sternum) is a common symptom of gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Right hypochondrial pain may originate from the gall bladder or biliary tract. Biliary pain can also be epigastric. Biliary pain is typically intermittent and severe, lasts a few hours and remits spontaneously to recur weeks or months later. Hepatic congestion (e.g. in hepatitis or cardiac failure) and sometimes peptic ulcer disease can present with pain in the right hypochondrium. Chronic, persistent or constant pain in the right (or left) hypochondrium in a well-looking patient is a frequent functional symptom; this chronic pain is not due to gall bladder disease.

Lower abdominal pain

Pain in the left iliac fossa may be colonic in origin (e.g. acute diverticulitis) but chronic pain is most commonly associated with functional bowel disorders.

Lower abdominal pain in women occurs in a number of gynaecological disorders and the differentiation from GI disease may be difficult.

Pain in the right iliac fossa may be due to acute appendicitis or ileocaecal disease, but may also commonly be functional.

Proctalgia fugax is a severe pain deep in the rectum that comes on suddenly but lasts only for a short time. It is not due to organic disease.

The acute abdomen

This accounts for approximately 50% of all urgent admissions to general surgical units. The acute abdomen is a consequence of one or more pathological processes.

• Inflammation. Pain develops gradually, usually over several hours. It is initially rather diffuse until the parietal peritoneum is involved, when it

becomes localised. Movement exacerbates the pain; abdominal rigidity and guarding occur.

• Perforation. When a viscus perforates, pain starts abruptly; it is severe and leads to generalized peritonitis.

• Obstruction. Pain is colicky, with spasms which cause the patient to writhe around and double up. Colicky pain which does not disappear between spasms suggests complicating inflammation.

Chronic or recurrent abdominal pain

A detailed history, with particular attention to the features of the pain and any associated symptoms is essential.Note should be made of the patient’s general demeanour, mood and emotional state, signs of weight loss, fever, jaundice or anaemia. If a thorough abdominal and rectal examination is normal, a careful search should be made for evidence of disease affecting other structures,

particularly the vertebral column, spinal cord, lungs and cardiovascular system.

Abdominal Swelling

Abdominal swelling or distention is a common problem in clinical medicine and may be the initial manifestation of a systemic disease or of otherwise unsuspected abdominal disease. Subjective abdominal enlargement, often described as a sensation of fullness or bloating, is usually transient and is often related to a functional gastrointestinal disorder when it is not accompanied by objective physical findings of increased abdominal girth or local swelling. Obesity and lumbar lordosis, which may be associated with prominence of the abdomen, may usually be distinguished from true increases in the volume of the peritoneal cavity by history and careful physical examination.

Flatulence

This term describes excessive wind. It is used to indicate belching, abdominal distension, gurgling and the passage of flatus per rectum. Some of the swallowed air passes into the intestine where most of it is absorbed, but some remains to be passed rectally. Colonic bacterial breakdown of nonabsorbed carbohydrate also produces gas. Causesof increased gas production and intake include high-fibre diet

and carbonated drinks.