1

Babylon University Stage Fourth

College of Medicine Lecture 2

Dr. Athraa Falah

THE HEPATIC PATHOLOGY

Hepatitis C Virus

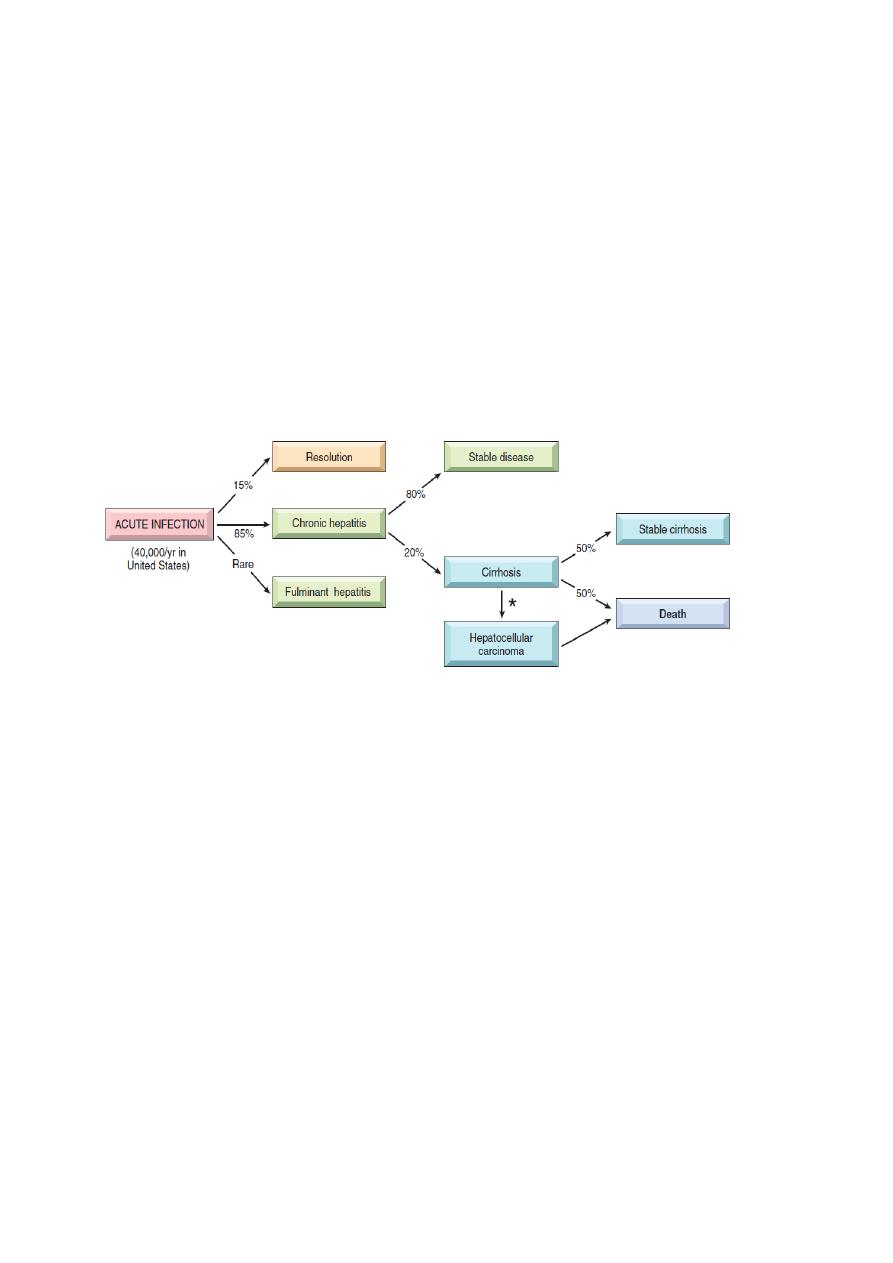

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of liver disease worldwide and it

is the most common chronic blood-borne infection. In contrast to HBV, progression to chronic

disease occurs in the majority of HCV-infected individuals, and cirrhosis may develop over 5 to

20 years after acute infection in 20% to 30% of patients with persistent infection.

The potential outcomes of hepatitis C infection in adults, with their approximate annual frequencies in the United

States.

The most common risk factors for HCV infection are:

• Intravenous drug abuse (most common risk factor)

• Multiple sex partners

• Having had surgery within the last 6 month

• Needle stick injury

• Multiple contacts with an HCV-infected person

• Employment in medical or dental fields (least one)

• Unknown (32%)

For children, the major route of infection is perinatal, but is much lower than for HBV (6% vs.

20%).

In about 85% of individuals, the clinical course of the acute infection is asymptomatic and easily

missed. The clinical course of acute HCV hepatitis is milder than that of HBV.

2

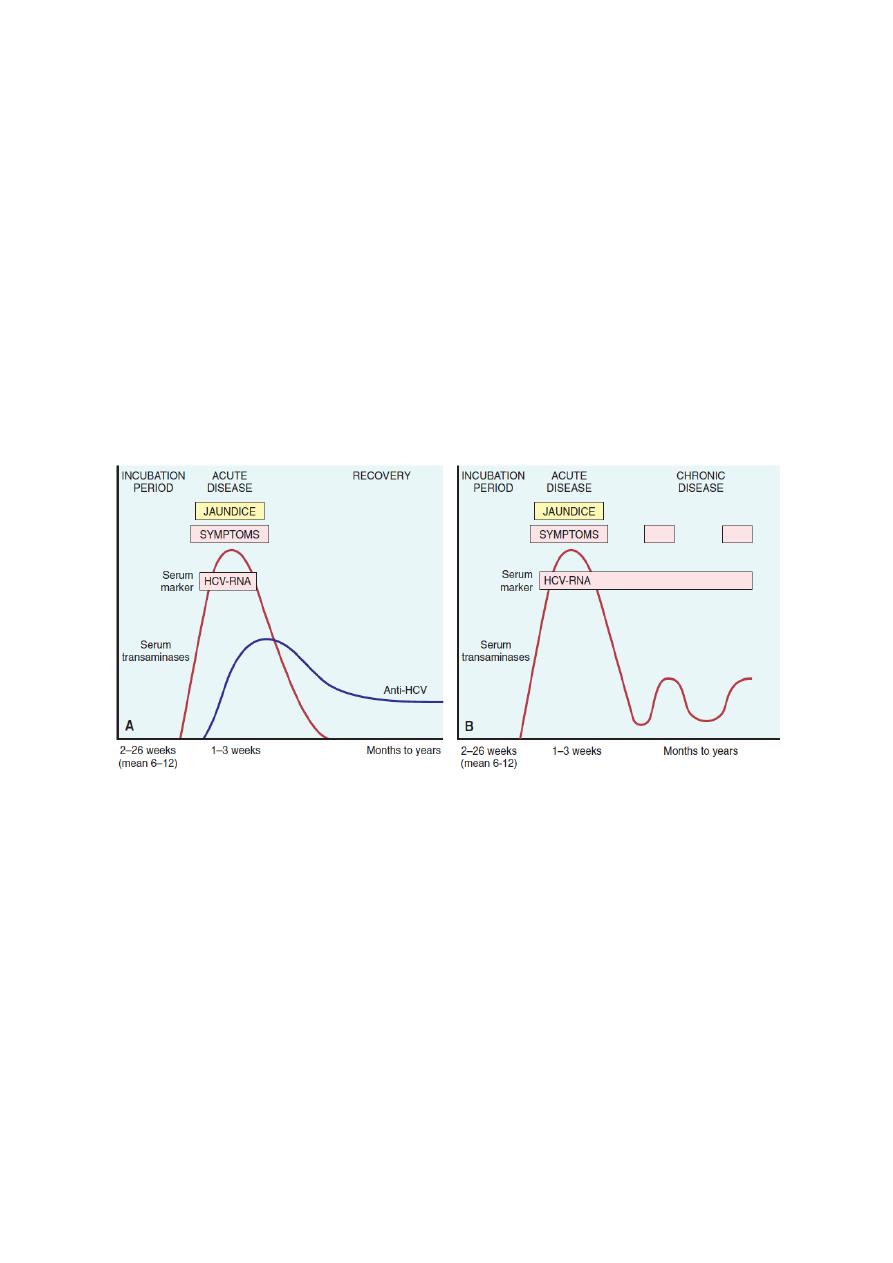

Serologic markers for HCV hepatitis

-HCV RNA is detectable in blood for 1 to 3 weeks, coincident with elevations in serum

transaminases.

-In symptomatic acute HCV infection, anti-HCV antibodies are detected in only 50% to 70% of

patients; in the remaining patients, the anti-HCV antibodies emerge after 3 to 6 weeks.

-In chronic HCV infection, circulating HCV RNA persists in many patients despite the presence

of neutralizing antibodies, including more than 90% of patients with chronic disease (Fig. below ).

-Hence, in persons with chronic hepatitis, HCV RNA testing must be performed to assess viral

replication and to confirm the diagnosis of HCV infection.

-A clinical feature that is quite characteristic of chronic HCV infection is episodic elevations in

serum aminotransferases, with intervening normal or near-normal periods.

Sequence of serologic markers for HCV hepatitis. A, Acute infection with resolution; B, progression to chronic

infection.

Hepatitis D Virus (H Delta virus)

HDV is a unique RNA virus that is dependent for its life cycle on HBV. Infection with HDV

arises in the following settings.

• Acute coinfection occurs following exposure to serum containing both HDV and HBV.

• Superinfection occurs when a chronic carrier of HBV is exposed to a new inoculum of

HDV.

• Helper-independent latent infection observed in the liver transplant setting.

Infection by HDV is worldwide. 20-40% of HbsAg carriers may have anti-HDV antibody,

although there has been a definite decline in recent years.

3

Diagnosis.

-HDV RNA is detectable in the blood and liver just before and in the early days of acute

symptomatic disease.

-IgM anti-HDV is the most reliable indicator of recent HDV exposure. Nevertheless, acute co-

infection by HDV and HBV is best indicated by detection of IgM against both HDAg and HBcAg

(denoting new infection with hepatitis B).

Treatment of HDV infection is limited to IFN-α. Other antiviral agents for HBV have not shown

effectiveness. Vaccination for HBV can also prevent HDV infection.

Hepatitis E Virus

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) hepatitis is an enterically trans-mitted, water-borne infection that occurs

primarily in young to middle-aged adults; sporadic infection and overt illness in children are rare.

HEV is a zoonotic disease with animal reservoirs, such as monkeys, cats, pigs, and dogs.

A characteristic feature of HEV infection is the high mortality rate among pregnant women,

approaching 20%. In most cases the disease is self-limiting; HEV is not associated with chronic

liver disease or persistent viremia. The average incubation period is 6 weeks.

Diagnosis.

-Before the onset of clinical illness, HEV RNA and HEV virions can be detected by PCR in stool

and serum.

-The onset of rising serum aminotransferases, clinical illness, and elevated IgM anti-HEV titers

are virtually simultaneous.

-Symptoms resolve in 2 to 4 weeks, during which time the IgM is replaced with a persistent IgG

anti-HEV titer.

Chronic Hepatitis.

Chronic hepatitis is defined as symptomatic, biochemical, or serologic evidence of continuing or

relapsing hepatic disease for more than 6 months.

The clinical features of chronic hepatitis are extremely variable . In some patients the only signs of

chronic disease are persistent elevations of serum transaminases. The most common symptom is

fatigue; less common symptoms are malaise, loss of appetite, and occasional bouts of mild

jaundice.

Physical findings are few, the most common being spider angiomas, palmar erythema, mild

hepatomegaly, hepatic tenderness, and mild splenomegaly, occasionaly vasculitis (subcutaneous

or visceral,) and glomerulonephritis.

Laboratory studies may reveal prolongation of the prothrombin time and, in some instances,

hyperglobulinemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and mild elevations in alkaline phosphatase levels.

4

The development of chronic infection after exposure to HBV is an important clinical problem. Age

at the time of infection is the best determinant of chronicity. The younger the age at the time of

infection, the higher the probability of chronicity.

Despite progress in the treatment of chronic HBV infection, complete cure is extremely difficult to

achieve.

HCV is by far the most common cause of chronic viral hepatitis. The clinical diagnosis may not be

apparent because patients with chronic HCV infection often have mild or no symptoms. However,

even patients with normal transaminases are at high risk of developing permanent liver damage.

Therefore, any individual with detectable HCV RNA in the serum needs medical attention.

HCV infection is potentially curable. Treatment is currently based on combination of pegylated

IFN-α and ribavirin.

The Carrier State.

A “carrier” in the case of hepatotropic virus can be interpreted to mean:

(1) individuals who carry one of the viruses but have no liver disease;

(2) those who harbor one of the viruses and have non-progressive liver damage, but are essentially

free of symptoms or disability.

In both cases, particularly the latter, these individuals constitute reservoirs for infection.

In the case of HBV infection a “healthy carrier” is often defined as an individual with continuous

presence of Hbs Ag ,without HBeAg, but with presence of anti-HBe, normal aminotransferases,

low or undetectable serum HBV DNA, and a liver biopsy showing a lack of significant

inflammation and necrosis.

In non-endemic areas such as the United States, less than 1% of HBV infections acquired by

adults produces a carrier state.

In contrast, HBV infection acquired early in life in endemic areas (such as Southeast Asia, China,

and Sub-Saharan Africa) gives rise to a carrier state in more than 90% of cases.

Morphology of Acute and Chronic Hepatitis.

The morphologic changes in acute and chronic viral hepatitis are shared among the hepatotropic viruses

from A to E.

A few histologic changes may be indicative of a particular type of virus. HBV-infected

hepatocytes may show a cytoplasm packed with spheres and tubules of HBsAg, producing cell

with large ,pale, finely granular, pink cytoplasmic inclusions on hematoxylin-eosin staining

(“ground-glass hepatocytes,”).

HCV-infected livers frequently show lymphoid aggregates within portal tracts and focal lobular

regions of hepatocyte macrovesicular steatosis (fatty change).

5

Acute Hepatitis. Hepatocyte injury takes the form of diffuse swelling (“ballooning

degeneration”;), so the cytoplasm looks empty and contains only scattered eosinophilic remnants

of cytoplasmic organelles. An inconstant finding is cholestasis, with bile plugs in canaliculi and

brown pigmentation of hepatocytes.

Several patterns of hepatocyte cell death are seen.

• Rupture of the cell membrane leads to cell death and focal loss of hepatocytes, and

scavenger macrophage aggregates mark sites of hepatocyte loss.

• Apoptosis, Apoptotic hepatocytes shrink, become intensely eosinophilic, and have

fragmented nuclei (councilman bodies)

• In severe cases of acute hepatitis, confluent necrosis of hepatocytes may lead to bridging

necrosis connecting portal-to-portal, central-to-central, or portal-to-central regions of

adjacent lobules.

Inflammation is a characteristic and usually prominent feature of acute hepatitis. The portal

tracts are usually infiltrated with a mixture of inflammatory cells. The inflammatory infiltrate

may spill over into the adjacent parenchyma, causing apoptosis of periportal hepatocytes. This is

known as interface hepatitis (piecemeal necrosis), which can occur in acute and chronic

hepatitis.

Chronic Hepatitis. The histologic features of chronic hepatitis range from exceedingly mild to

severe.

In the mildest forms, inflammation is limited to portal tracts and consists of lymphocytes,

macrophages, occasional plasma cells, and rare neutrophils or eosinophils. Liver architecture is

usually well preserved, but smoldering hepatocyte apoptosis throughout the lobule may occur in

all forms of chronic hepatitis.

In chronic HCV infection, common findings are lymphoid aggregates and focal mild to moderate

fatty change of liver.

In all forms of chronic hepatitis, continued interface hepatitis and bridging necrosis between

portal tracts and portal tracts-to-terminal hepatic veins, are harbingers of progressive liver damage.

The hallmark of chronic liver damage is the deposition of fibrous tissue. At first, only portal

tracts show increased fibrosis, but with time periportal septal fibrosis occurs, followed by linking

of fibrous septa (bridging fibrosis), especially between portal tracts.

Continued loss of hepatocytes and fibrosis results in cirrhosis.

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis is a chronic and progressive hepatitis of unknown etiology .The

pathogenesis is attributed to T cell–mediated autoimmunity, in which hepatocyte injury is caused

by IFN-γ produced by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and by CD8+ T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity.

Genetic factors likely play a role in the autoimmunity .

6

The injurious immune reaction may be triggered by viral infections, certain drugs and herbal

products. Autoimmune hepatitis commonly occurs concurrently with other autoimmune disorders,

such as celiac disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and other.

Clinicopathologic Features.

The disease may run an indolent or severe course (including fulminant hepatitis). There is a female

predominance particularly in young and perimenopausal women. The annual incidence is highest

among white northern Europeans.

The charecteristic features include:

1-absence of serologic markers of viral infection,

2-elevated serum IgG and γ-globulin levels (1.2 to 3.0 times normal), and

3-high serum titers of autoantibodies.

Autoimmune hepatitis is classified into types 1 and 2, based on the patterns of circulating

antibodies.

Type 1 is characterized by the presence of antinuclear (ANA), anti–smooth muscle

(SMA). The main antibodies detected in Type 2 autoimmune hepatitis are anti–liver kidney

microsome-1 (ALKM-1) antibodies, and anti–liver cytosol-1 (ACL-1).

The entire histologic spectrum of chronic hepatitis may be seen in autoimmune hepatitis, but it is

marked by prominent inflammatory infiltrates of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Clusters of plasma cells in the interface of portal tracts and hepatic lobules are fairly

characteristic for autoimmune hepatitis.

Symptomatic patients with autoimmune hepatitis tend to show substantial liver destruction and

scarring at the time of diagnosis. Alternatively, autoimmune hepatitis may present in an atypical

fashion with symptoms primarily from involvement of other organ systems, or may be

asymptomatic and progress to cirrhosis without clinical diagnosis.

The mortality of patients with severe untreated autoimmune hepatitis is approximately 40% within

6 months of diagnosis, and cirrhosis develops in at least 40% of survivors. .

ALCOHOLIC LIVER DISEASE

-Alcohol is a direct hepatotoxic agent.

-15% of alcoholics can be expected to develop cirrhosis.

-The amount of alcohol necessary to produce chronic liver disease is about 80g/day .

-Women are more susceptible to produce alcoholic liver damage than men.

-Alcohol is metabolized by the liver to acetaldehyde and acetate; it is oxidized through the enzyme

alcohol dehydrogenase and a microsomal ethanol oxidation system(MEOS)

7

There are three distinctive, overlapping, forms of alcoholic liver disease:

(1) hepatic steatosis (fatty liver disease),

(2) alcoholic hepatitis, and

(3) cirrhosis .

Morphology.

Hepatic Steatosis (Fatty Liver). After even moderate intake of alcohol, microvesicular lipid

droplets accumulate in hepatocytes. With chronic intake of alcohol, lipid accumulates creating

large, clear macrovesicular globules that compress and displace the hepatocyte nucleus to the

periphery of the cell.

Macroscopically, the fatty liver of chronic alcoholism is a large (as heavy as 4 to 6 kg), soft organ

that is yellow and greasy. The fatty change is completely reversible if the person will stop

alcohol intake.

Pathogenesis

(1) shunting of normal substrates away from catabolism and toward lipid biosynthesis(Alcohol

increases fatty synthesis), as a result of generation of excess reduced nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide (NADH + H

+

) by the two major enzymes of alcohol metabolism, alcohol

dehydrogenase and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase;

(2) impaired assembly and secretion of lipoproteins; and

(3) increased peripheral catabolism of fat.

Clinical Features.

Hepatic steatosis (fatty liver) may become evident as hepatomegaly, with mild elevation of serum

bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels. Severe hepatic dysfunction is unusual.

Alcoholic Hepatitis (Alcoholic Steatohepatitis). Alcoholic hepatitis is It is an acute inflammation,

characterized by characterized by:

1. Hepatocyte swelling and necrosis: Single or scattered foci of cells undergo swelling

(ballooning) and necrosis. The swelling results from the accumulation of fat and water, as

well as proteins that normally are exported.

2. Mallory bodies: Scattered hepatocytes accumulate intermediate (cytokeratin) filaments

such as cytokeratin 8 and 18, in complex with other proteins(Mallory bodies). Mallory

bodies are visible as eosinophilic cytoplasmic clumps in hepatocytes. These inclusions are

a characteristic but not specific feature of alcoholic liver disease.

3. Neutrophilic reaction: Neutrophils accumulate around degenerating hepatocytes,

particularly those having Mallory bodies. Lymphocytes and macrophages also enter portal

tracts and spill into the parenchyma.

4. Fibrosis: Alcoholic hepatitis is almost always accompanied by prominent activation of

8

sinusoidal stellate cells and portal tract fibroblasts, giving rise to fibrosis. Most frequently

fibrosis is sinusoidal and perivenular, separating parenchymal cells.

Pathogenesis

The causes of alcoholic hepatitis are uncertain but some of the factors in its pathogenesis are.

- Acetaldehyde (the major intermediate metabolite of alcohol) induces lipid peroxidation and

acetaldehyde-protein adduct formation, further disrupting cytoskeletal and membrane function.

-Cytochrome P-450 metabolism produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) that react with cellular

proteins, damage membranes, and alter hepatocellular function.

-Alcohol-induced impaired hepatic metabolism of methionine leads to decreased intrahepatic

glutathione levels, thereby sensitizing the liver to oxidative injury.

-Cytokine-mediated inflammation and cell injury is a major feature of alcoholic hepatitis. TNF is

considered to be the main effector of injury; IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8 may also contribute. The main

stimuli for production of cytokines in alcoholic liver disease are the ROS, and microbial products

(e.g., endotoxine) derived from gut bacteria.

Clinical Features.

Patients present with acute symptoms: right upper quadrant pain, anorexia, fever and jaundice.

Serum enzymes are abnormal and the white count may reach 25000. Mortality rate can reach up to

20%.

C) Alcoholic cirrhosis:

Fatty liver and alcoholic hepatitis may lead to cirrhosis in about 15% of alcoholics. The term

denotes the formation of fibrous septa surrounding hepatocellular nodules. Alcoholic cirrhosis is

one of the most common causes for liver transplantation, since it is usually considered as end

stage liver disease.

Clinical Features.

The manifestations of alcoholic cirrhosis are similar to those of other forms of cirrhosis.

Laboratory findings include elevated serum aminotransferase, hyperbilirubinemia, variable

elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase, hypoproteinemia, and anemia.

The long-term outlook for alcoholics with liver disease is variable. In the end-stage alcoholic the

proximate causes of death are (1) hepatic coma, (2) massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage, (3)

intercurrent infection (to which these patients are predisposed), (4) hepatorenal syndrome

following a bout of alcoholic hepatitis, and (5) hepatocellular carcinoma (the risk of developing

this tumor in alcoholic cirrhosis is 1% to 6% of cases annually).