Infective endocarditis

Pathophysiologytypically occurs at sites of preexisting endocardial damage

virulent or aggressive organisms (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus) can cause endocarditis in a previously normal heart

Many acquired and congenital cardiac lesions are vulnerable to endocarditis, particularly areas of endocardial damage caused by a high-pressure jet of blood

The avascular valve tissue and presence of fibrin and platelet aggregates help to protect proliferating organisms from host defence mechanisms

vegetations composed of organisms, fibrin and platelets grow and may become large enough to cause obstruction or embolism

Extracardiac manifestations, such as vasculitis and skin lesions, are due to emboli or immune complex deposition

Microbiology

Over three-quarters of cases are caused by streptococci or staphylococciStrep. milleri and Strep. bovis endocarditis is associated with large-bowel neoplasms.

Staph. aureus has now overtaken streptococci as the most common cause of acute endocarditis

Post-operative endocarditis .The most common organism is a coagulase-negative staphylococcus (Staph. epidermidis)

Q fever endocarditis due to Coxiella burnetii, : contact with farm animals. The aortic valve is usually affected and there may also be hepatitis, pneumonia and purpura. Life-long antibiotic therapy may be required.

HACEK are slow-growing, fastidious organisms that are only revealed after prolonged culture and may be resistant to penicillin.

Brucella

Yeasts and fungi (Candida, Aspergillus)

Microbiology of infective endocarditis

Incidence

5 to 15 cases per 100 000 per annum50% of patients are over 60 years

rheumatic heart disease in 24%congenital heart disease in 19%

other cardiac abnormalities (calcified aortic valve, floppy mitral valve) in 25%

32% were not thought to have a pre-existing cardiac abnormality

Clinical features

Subacute endocarditis

Acute endocarditisPost-operative endocarditis

modified Duke criteria

Investigations

Blood cultureEchocardiography

ESR , CRP , CBC

ECG

CXRManagement

The case fatality of bacterial endocarditis is approximately 20 %A multidisciplinary approach increases the chance of better outcome

Empirical treatment depends on the mode of presentation, the suspected organism, and whether the patient has a prosthetic valve or penicillin allergyIf the presentation is acute, flucloxacillin and gentamicin are recommended, while for a subacute or indolent presentation, benzyl penicillin and gentamicin are preferred

In those with penicillin allergy, a prosthetic valve or suspected meticillin-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA) infection, triple therapy with vancomycin, gentamicin and oral rifampicin should be considered

A 2-week treatment regimen may be sufficient for fully sensitive strains of Strep. viridans and Strep. bovis, provided specific conditions are met

Conditions for the short-course treatmentof Strep. viridans/bovis endocarditis

• Native valve infection• MIC ≤ 0.1 mg/L

• No adverse prognostic factors (e.g. heart failure, aortic regurgitation, conduction defect)

• No evidence of thromboembolic disease

• No vegetations > 5 mm diameter

• Clinical response within 7 days

Antimicrobial treatment of common causative organisms in infective endocarditis

Indications for cardiac surgery ininfective endocarditis

• Heart failure due to valve damage• Failure of antibiotic therapy (persistent/uncontrolled infection)

• Large vegetations on left-sided heart valves with evidence or‘high risk’ of systemic emboli

• Abscess formation

N.B. Patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis or fungal endocarditis often require cardiac surgery.

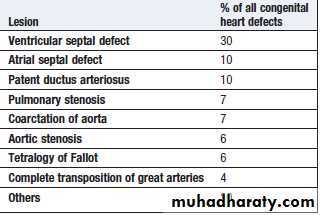

CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

Aetiology and incidence

0.8% of live births

Maternal infection or exposure to drugs or toxins may cause congenital heart disease.

Rubella , alcohol , SLEGenetic or chromosomal abnormalities, such as Down’s syndrome , Marfan syndrom and Digeorge syndrom

Clinical features

Clinical signs vary with the anatomical lesionSymptoms may be absent, or the child may be breathless or fail to attain normal growth and development

Some defects are not compatible with extrauterine life

Features of other congenital conditions, such as Marfan’s syndrome or Down’s syndrome, may also be apparentEarly diagnosis is important because many types of congenital heart disease are amenable to surgery

Central cyanosis and digital clubbing

Growth retardation and learning difficulties

SyncopePulmonary hypertension and Eisenmenger’s syndrome

Pregnancy• Obstructive lesions (e.g. severe aortic stenosis): poorly tolerated and associated with significant maternal morbidity and mortality.

Cyanotic conditions (e.g. Eisenmenger’s syndrome): especially poorly tolerated and pregnancy should be avoided.

Surgically corrected disease: patients often tolerate pregnancy well.

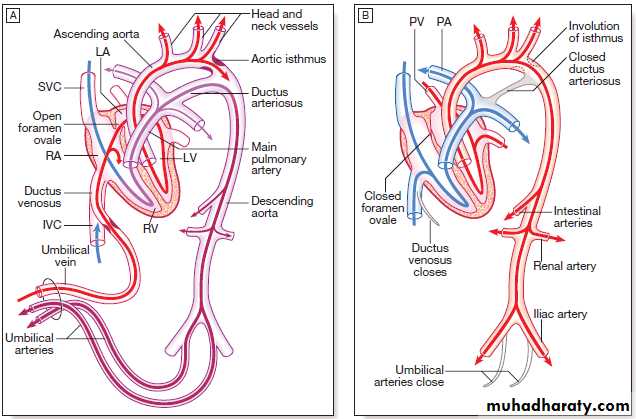

• Children of patients with congenital heart disease: 2–5% will be born with cardiac abnormalities, especially if the mother is affected.Persistent ductus arteriosus

Aetiology

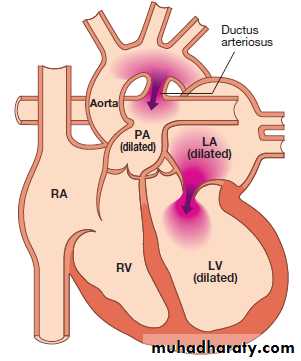

Normally, the ductus closes soon after birth but sometimes fails to do so

Persistence of the ductus is associated with other abnormalities and is more common in females.there will be a continuous arteriovenous shunt

50% of the left ventricular output is recirculated through the lungsClinical features

small shunts there may be no symptoms for yearswhen the ductus is large, growth and development may be retarded

cardiac failure may eventually ensue, dyspnoea being the first symptomcontinuous ‘machinery’ murmur is heard

Persistent ductus with reversed shuntingManagement

A patent ductus is closed at cardiac catheterisation with an implantable occlusive device

Pharmacological treatment in the neonatal period (prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor (indometacin or ibuprofen)Coarctation of the aorta

Aetiologyoccurs in the region where the ductus arteriosus joins the aorta, i.e. at the isthmus just below the origin of the left subclavian artery

twice as common in males and occurs in 1 in 4000 children

associated with other abnormalities, most frequently bicuspid aortic valve and ‘berry’ aneurysms of the cerebral circulationAcquired coarctation of the aorta is rare but may follow trauma or occur as a complication of a progressive arteritis (Takayasu’s disease)

Clinical features and investigations

coarctation is an important cause of cardiac failure in the newbornsymptoms are often absent when it is detected in older children or adults

Headaches , weakness or cramps in the legs , BP is raised in the upper body

Radiofemoral delay , systolic murmur may be be heard posteriorly or in the aortic area with ejection click due to bicuspid AV

CXR …… 3 sign and rib notching

ECG ….LVH

Echo. …..Confirm the diagnosis

MRI is the best imaging modality

Management

In untreated cases, death may occur from left ventricular failure, dissection of the aorta or cerebral haemorrhage.Surgical correction is advisable in most cases

Patients repaired in late childhood or adult life often remain hypertensive or develop recurrent hypertension later onRecurrence of stenosis may occur as the child grows and this may be managed by balloon dilatation and sometimes stenting

Coexistent bicuspid aortic valve, which occurs in over 50% of cases, may lead to progressive aortic stenosis or regurgitation, and also requires long-term follow-up.

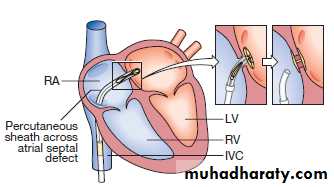

Atrial septal defect

one of the most common congenital heart defectstwice as frequently in females

Most are ‘ostium secundum’ defects

Ostium primum’ defects result from a defect in the atrioventricular septum and are associated with a ‘cleft mitral valve’ (split anterior leaflet).

Pulmonary hypertension and shunt reversal sometimes complicate atrial septal defect, but are less common and tend to occur later in life

Clinical features and investigations

SymptomsAsymptomatic

Dyspnea

Chest infection

HF

Arrythmias , AF

Signs

Wide fixed splitting S2Systolic flow murmur

Diastolic flow murmur

Investigations

ECG :- RBBB , RAD and in case of primum defect LAD

CXR : cardiomegaly ; pul plethora , prominent PA

Echo :- shows the defect , RV and PA dilatationTEE

TEEManagement

Atrial septal defects in which pulmonary flow is increased 50% above systemic flow (i.e. flow ratio of 1.5 : 1) are often large enough to be clinically recognisable and should be closedCath or surgery

Severe pulmonary hypertension and shunt reversal are both contraindications to closureVentricular septal defect

AetiologyCongenital and acquired

Embryologically, the interventricular septum has a membranous and a muscular portion

Most congenital defects are ‘perimembranousthe most common congenital cardiac defect, occurring once in 500 live births.

Acquired ventricular septal defect may result from rupture as a complication of acute MI or, rarely, from trauma.Clinical features

pansystolic murmur, usually heard best at the left sternal edge but radiating all over the precordiummaladie de Roger :- small defect producing loud murmur in the absence of other haemodynamic disturbance

Congenital ventricular septal defect may present as cardiac failure in infants, as a murmur with only minor haemodynamic disturbance in older children or adults, or, rarely, as Eisenmenger’s syndrome

If cardiac failure complicates a large defect, it only becomes apparent in the first 4–6 weeks of life

The chest X-ray shows pulmonary plethora and the ECG shows bilateral ventricular hypertrophy.

Echo .

Management and prognosis

Small ventricular septal defects require no specific treatmentHF : digoxin and diuretics

Persisting failure is an indication for closure of the defect by cath. or surgeryExcept in Eisenmenger’s syndrome, long-term prognosis is very good in congenital ventricular septal defect

Tetralogy of Fallot

Aetiology

The embryological cause is abnormal development of the bulbar septum that separates the ascending aorta from the pulmonary artery

The defect occurs in about 1 in 2000 births and is the most common cause of cyanosis in infancy after the first year of life.

Clinical features

Children are usually cyanosed but this may not be the case in the neonateThe subvalvular component of the RV outflow obstruction is dynamic and may increase suddenly under adrenergic stimulation

Fallot’s spells

In older children, Fallot’s spells are uncommon but cyanosis becomes increasingly apparent, with stunting of growth, digital clubbing and polycythaemia

Fallot’s sign : Some children characteristically obtain relief by squatting after exertion

On examination, cyanosis with a loud ejection systolic murmur in the pulmonary area

cyanosis may be absent in the newborn or in patients with only mild right ventricular outflow obstruction (‘acyanotic tetralogy of Fallot’)

Investigations and management

ECG … RVHCXR … boot shaped heart

Echo … Dx

The definitive management is total surgical correction

If the pulmonary arteries are too hypoplastic, then palliation in the form of a Blalock–Taussig shuntThe prognosis after total correction is good

ICD is sometimes recommended in adulthood.