Dr. Ahmed Saleem

FICMS

TUCOM / 3rd Year / 2015

NUTRITION IN SURGICAL PATIENT

Malnutrition is common in surgical patient. There is strong evidence, that patients who suffer starvation or

have signs of malnutrition have a higher risk of complications and an increased risk of death in comparison

with patients who have adequate nutritional reserves.

Pathophysiology

Metabolic response to starvation

Hepatic and muscle glycogenolysis: After a short fast lasting 12 hours or less, most food from the

last meal will have been absorbed. Plasma insulin levels fall and glucagon levels rise, which

facilitates the conversion of 200 g of liver glycogen into glucose. The liver, therefore, becomes an

organ of glucose production under fasting conditions. Many organs, including brain tissue, red and

white blood cells and the renal medulla, can initially utilize only glucose for their metabolic needs.

Additional stores of glycogen exist in muscle (500 g), but these cannot be utilized directly. Muscle

glycogen is broken down (glycogenolysis) and converted to lactate, which is then exported to the

liver where it is converted to glucose (Cori cycle).

Protein catabolism and hepatic gluconeogenesis: With increasing duration of fasting (>24 hours),

glycogen stores are depleted and de novo glucose production from non-carbohydrate precursors

(gluconeogenesis) takes place, predominantly in the liver. Most of this glucose is derived from the

breakdown of amino acids, particularly glutamine and alanine as a result of catabolism of skeletal

muscle. This protein catabolism in simple starvation is readily reversed with the provision of

exogenous glucose.

Lipolysis and adaptive ketogenesis: With more prolonged fasting there is an increased reliance on

fat oxidation to meet energy requirements. Increased breakdown of fat stores occurs, providing

glycerol, which can be converted to glucose, and fatty acids, which can be used as a tissue fuel by

almost all of the body’s tissues. Hepatic production of ketones from fatty acids is facilitated by low

insulin levels and, after 48–72 hours of fasting, the central nervous system may adapt to using

ketone bodies as their primary fuel source. This conversion to a ‘fat fuel economy’ reduces the need

for muscle breakdown. Despite these adaptive responses, there remains an obligatory glucose

requirement of about 200 g per day, even under conditions of prolonged fasting

Reduction in resting energy expenditure: possibly mediated by a decline in the conversion of

inactive thyroxine (T4) to active tri-iodothyronine (T3).

Nutritional changes in metabolic response to trauma and sepsis

From a nutritional point of view, two factors deserve emphasis:

1) In contrast to simple starvation, patients with trauma have impaired formation of ketones and the

breakdown of protein to synthesize glucose (gluconeogenesis) cannot be entirely prevented by the

administration of glucose.

2) Although the metabolic response to trauma and sepsis is always associated with hypermetabolism

or hypercatabolism; these terms are ill defined and do not indicate the need for very high-energy

intakes. The provision of high-energy intakes is not associated with an amelioration of the catabolic

process and it may indeed be harmful.

Page 1 of 6

Nutritional assessment

Laboratory techniques

There is no single biochemical measurement that reliably identifies malnutrition.

Albumin is not a measure of nutritional status. Although a low serum albumin level (<30 g/L) is

an indicator of poor prognosis; hypoalbuminemia invariably occurs because of alterations in

body fluid composition and because of increased capillary permeability related to ongoing sepsis.

Lymphocyte count and skin testing for delayed hypersensitivity frequently reveal abnormalities

in malnourished patients. Immunity is not, however, a precise or reliable indicator of nutritional

status, nor is it a practical method in routine clinical practice.

Body weight and anthropometry

A simple method of assessing nutritional status is to estimate weight loss; measured body

weight is compared with ideal body weight.

Body weight is frequently corrected for height, allowing calculation of the body mass index

(BMI, defined as body weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). A BMI of less

than 18.5 indicates nutritional impairment.

Major changes in fluid balance, which are common in critically ill patients, may make body

weight and BMI unreliable indicators of nutritional status.

Anthropometric techniques incorporating measurements of skinfold thicknesses and mid-arm

circumference permit estimations of body fat and muscle mass, and these are indirect measures

of energy and protein stores. These measurements are, however, insufficiently accurate in

individual patients to permit planning of nutritional support regimens and significantly impaired

by the presence of edema.

Clinical

The term ‘subjective global assessment’ encompasses historical, symptomatic and physical

parameters: The possibility of malnutrition should form part of the work up of all patients. A clinical

assessment of nutritional status involves a focused history and physical examination and selected

laboratory tests aimed at detecting specific nutrient deficiencies.

Nutritional requirements

Normal physiology relies on three essential substrates: carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids, which provide

both an energy source and the substrates for chemical building blocks. Total enteral or parenteral nutrition

necessitates the provision of the macronutrients, carbohydrate, fat and protein, together with vitamins,

trace elements, electrolytes and water. When planning a feeding regimen, the patient should be weighed

and an assessment made of daily energy and protein requirements.

Energy

Energy needs can be measured by direct calorimetry or less accurately by indirect calorimetry and

predictive equations. It is known that various conditions can increase metabolic rate from 10% to

100% above basal metabolic rate (BMR) (e.g., trauma, burns, etc.). The total energy requirement of

a stable patient with a normal or moderately increased need is approximately 20–30 kcal/kg per

day. Very few patients require energy intakes in excess of 2000 kcal/day.

Page 2 of 6

Carbohydrate

Carbohydrates largely in the form of glucose supply 3.4 kcal of energy/g. There is an obligatory

glucose requirement to meet the needs of the central nervous system and certain hematopoietic

cells, which is equivalent to about 2 g/kg per day. In addition, there is a physiological maximum to

the amount of glucose that can be oxidized, which is approximately 4 mg/kg per minute. However,

optimal utilization of energy during nutritional support is ensured by avoiding the infusion of

glucose at rates approximating physiological maximums. Plasma glucose levels provide an indication

of tolerance. Avoid hyperglycemia. Provide energy as mixtures of glucose and fat. Glucose is the

preferred carbohydrate source.

Fat

Dietary fat is composed of triglycerides of predominantly long-chain fatty acids. The unsaturated

fatty acids, linoleic and linolenic acids are considered essential because they cannot be synthesized

in vivo from non-dietary sources. Essential fatty acids are required for the production of sterol-

based hormones and prostaglandins. Both soybean and sunflower oil emulsions are rich sources of

linoleic acid and provision of only 1 liter of emulsion per week avoids deficiency. Safe and non-toxic

fat emulsions based upon long-chain triglycerides (LCTs) have been commercially available for over

30 years. These emulsions provide a calorically dense product (9 kcal/g) and are now routinely used

to supplement the provision of non-protein calories during parenteral nutrition. Energy during

parenteral nutrition should be given as a mixture of fat together with glucose. There is no evidence

to suggest that any particular ratio of glucose to fat is optimal as long as under all conditions the

basal requirements for glucose (100–200 g/day) and essential fatty acids (100–200 g/week) are met.

This ‘dual energy’ supply minimizes metabolic complications during parenteral nutrition, reduces

fluid retention, enhances substrate utilization (particularly in the septic patient) and is associated

with reduced carbon dioxide production. If patients are being supported with parenteral nutrition

(PN), they should be monitored for tolerance of lipid delivery because long-chain triglyceride

solutions may diminish immune function, and cause hypertriglyceridemia; these complications may

be minimized by infusing lipids continuously over 18 to 24 hours and at a rate not to exceed 0.1

g/kg/hour. Once initiated, they can be given three times weekly to daily, depending on the

nutritional needs of the patient. There is a renewed interested in providing omega-3 fatty acid

containing nutrition therapy to patients, as they are considered anti-inflammatory.

Proteins

Proteins provide 4.0 kcal/g and account for 20% to 30% of the total daily caloric intake. Proteins and

amino acids are essential components of all living cells and are involved in virtually all bodily

functions. All protein in the body is functional. During metabolic stress, proteins are broken down

into amino acids and enter into the gluconeogenic pathway and used as a fuel source or form the

basic structural elements of living cells. It is important to realize there is no protein storage per se

and that any protein utilized for gluconeogenesis and acute-phase protein synthesis should be

considered a loss of functional protein. The basic requirement for nitrogen in patients without pre-

existing malnutrition and without metabolic stress is 0.10–0.15 g/kg per day. In hypermetabolic

patients, the nitrogen requirements increase to 0.20–0.25 g/kg per day.

Page 3 of 6

Vitamins, minerals and trace elements

Whatever the method of feeding, these are all essential components of nutritional regimens. The

water-soluble vitamins B and C act as coenzymes in collagen formation and wound healing.

Supplemental vitamin B12 is often indicated in patients who have undergone intestinal resection or

gastric surgery and in those with a history of alcohol dependence. Absorption of the fat-soluble

vitamins A, D, E and K is reduced in steatorrhoea and the absence of bile. Surgical patients who

require steroid medications and who have healing wounds should receive supplemental Vitamin A

to aid in collagen crosslinking. Vitamin K is essential for blood-clotting mechanism. Trace element

deficiencies of zinc, copper, manganese, and selenium can lead to impaired wound healing, glucose

metabolism, and protein sulfination. Normally, trace element requirements are met by the delivery

of food to the gut and so patients on long-term parenteral nutrition are at particular risk of

depletion. Supplementation is necessary to optimize utilization of amino acids and to avoid

refeeding syndrome.

Artificial nutritional support

Indications

The indications for nutritional support are simple; any patient who has sustained 5–7 days of inadequate

intake or who is anticipated to have no intake for this period should be considered for nutritional support.

The periods may be less in patients with pre-existing malnutrition. This concept is important because it

emphasizes that the provision of nutritional support is not specific to certain conditions or diseases.

Although patients with Crohn’s disease or pancreatitis, or those who have undergone gastrointestinal

resections, may frequently require nutritional support, it is the fact that they have had inadequate intakes

for defined periods that is the indication rather than the specific disease process.

Enteral nutrition

The term ‘enteral feeding’ means delivery of nutrients into the gastrointestinal tract. The alimentary tract

should be used whenever possible. This can be achieved with oral supplements (sip feeding) or with a

variety of tube-feeding techniques delivering food into the stomach, duodenum or jejunum. A variety of

nutrient formulations is available for enteral feeding. These vary with respect to energy content,

osmolarity, fat and nitrogen content and nutrient complexity. Polymeric feeds contain intact protein and

hence require digestion, whereas monomeric/elemental feeds contain nitrogen in the form of either free

amino acids or, in some cases, peptides.

Sip feeding: Commercially available supplementary sip feeds are used in patients who can drink but

whose appetites are impaired.

Tube-feeding techniques: Enteral nutrition can be achieved using conventional nasogastric tubes or

more fine-bore feeding tubes inserted into the stomach, surgical or percutaneous endoscopic

gastrostomy (PEG) or, finally, post-pyloric feeding utilizing nasojejunal tubes or various types of

jejunostomy. The choice of method will be determined by local circumstances and preference in

many patients.

Nasogastric tubes: are appropriate in a majority of patients. If feeding is maintained for more

than a week or so, a fine-bore feeding tube is preferable and is likely to cause fewer gastric and

esophageal erosions. These are usually made from soft polyurethane or silicone elastomer and

have an internal diameter of <3 mm.

Page 4 of 6

Gastrostomy: The placement of a tube through the abdominal wall directly into the stomach is

termed ‘gastrostomy’. Historically, these were created surgically at the time of laparotomy.

Today, the majority are performed by percutaneous insertion under endoscopic control using

local anesthesia, known as PEG (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) tubes. If patients

require enteral nutrition for prolonged periods, then PEG is preferable to an indwelling

nasogastric tube; this minimizes the traumatic complications related to indwelling tubes.

Jejunostomy: In recent years, the use of jejunal feeding has become increasingly popular. This

can be achieved using nasojejunal tubes or by placement of needle jejunostomy at the time of

laparotomy. The increasing use of jejunostomies is advocated on the basis that post-pyloric

feeding may be associated with a reduction in aspiration and enhanced tolerance of enteral

nutrition.

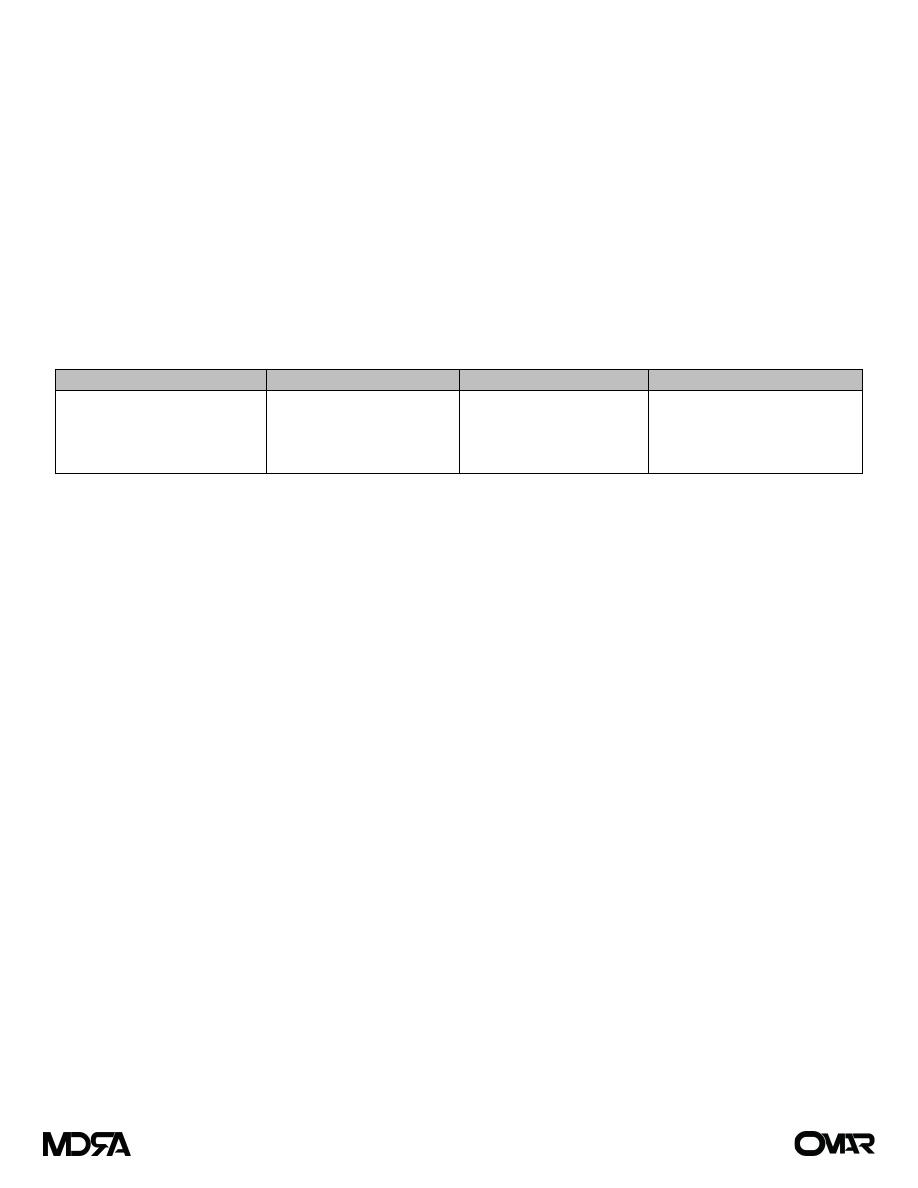

Complications of enteral nutrition

Gastrointestinal

Tube-related

Metabolic/biochemical

Infective

- Diarrhea

- Bloating, nausea, vomiting

- Abdominal cramps

- Aspiration

- Malposition

- Blockage

- Local complications (e.g.

erosion of skin/mucosa)

- Electrolyte disorders

- Vitamin, mineral, trace

element deficiencies

- Exogenous (handling

contamination)

- Endogenous (patient)

Parenteral nutrition

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is defined as the provision of all nutritional requirements by means of the

intravenous route and without the use of the gastrointestinal tract.

Parenteral nutrition is indicated when energy and protein needs cannot be met by the enteral

administration of these substrates. The most frequent clinical indications relate to those patients who have:

undergone massive resection of the small intestine.

intestinal fistula.

prolonged intestinal failure for other reasons.

Route of delivery:

TPN can be administered either by a catheter inserted in the central vein or via a peripheral line. In

the early days of parenteral nutrition, the only energy source available was hypertonic glucose,

which, being hypertonic, had to be given into a central vein to avoid thrombophlebitis. In the second

half of the last century, there were a number of important developments that have influenced the

administration of parenteral nutrition; these include:

the identification of safe and non-toxic fat emulsions that are isotonic

pharmaceutical developments that permit carbohydrates, fats and amino acids to be mixed

in single containers

recognition that the provision of energy during parenteral nutrition should be a mixture of

glucose and fat and that energy requirements are rarely in excess of 2000 kcal/day (25–30

kcal/kg per day).

These changes enabled the development of peripheral parenteral nutrition.

Page 5 of 6

1) Peripheral

Peripheral feeding is appropriate for short-term feeding of up to 2 weeks. Access can be

achieved either by means of a dedicated catheter inserted into a peripheral vein and

maneuvered into the central venous system (peripherally inserted central venous catheter

(PICC) line) or by using a conventional short cannula in the wrist veins. Peripheral parenteral

nutrition has the advantage that it avoids the complications associated with central venous

administration, but suffers the disadvantage that it is limited by the development of

thrombophlebitis. Peripheral feeding is not indicated if patients already have an indwelling

central venous line or in those in whom long-term feeding is anticipated.

2) Central

When the central venous route is chosen, the catheter can be inserted via the subclavian or

internal or external jugular vein. The infraclavicular subclavian approach is more suitable for

feeding as the catheter then lies flat on the chest wall, which optimizes nursing care.

Whichever technique is employed, a post-insertion chest x-ray is essential before feeding is

commenced to confirm the absence of pneumothorax and that the catheter tip lies in the

distal superior vena cava to minimize the risk of central venous or cardiac thrombosis.

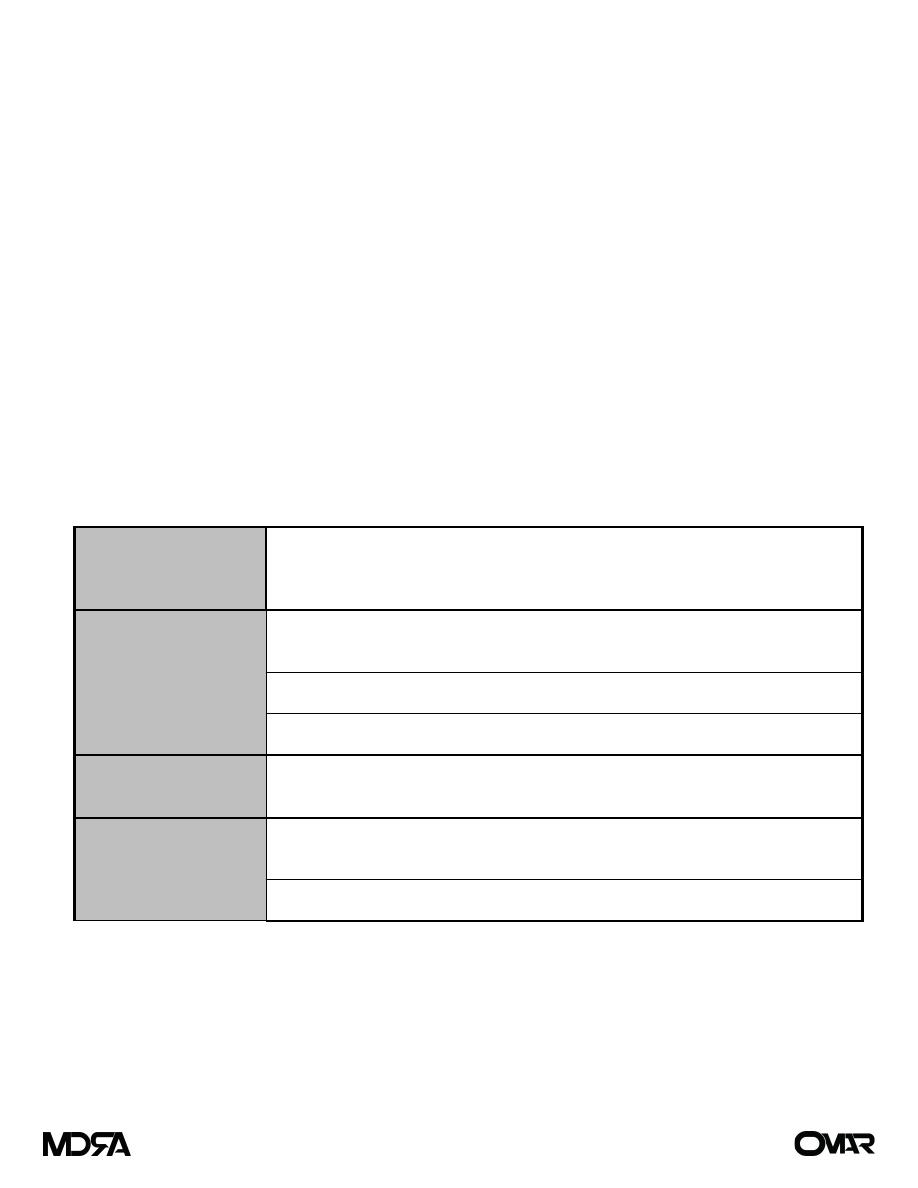

Complications of parenteral nutrition

Related to nutrient

deficiency

Hypoglycemia/hypocalcaemia/

hypophosphatemia/hypomagnesaemia (refeeding syndrome)

Chronic deficiency syndromes (essential fatty acids, zinc, mineral and trace elements)

Related to overfeeding

Excess glucose: hyperglycemia, hyperosmolar dehydration, hepatic steatosis,

hypercapnia, increased sympathetic activity, fluid retention, electrolyte abnormalities

Excess fat: hypercholesterolemia , hypertriglyceridemia, hypersensitivity reactions

Excess amino acids: hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, hypercalcaemia, uremia

Related to sepsis

Catheter-related sepsis

Possible increased predisposition to systemic sepsis

Related to line

On insertion: pneumothorax, damage to adjacent artery, air embolism, thoracic duct

damage, cardiac perforation or tamponade, pleural effusion

Long-term use: occlusion, venous thrombosis

Page 6 of 6