Exodontia Practice

Oral and maxillofacial surgery is a medical specialty

concerned with diagnosis and treatment of diseases of

jaws, teeth, mouth and face.

Exodontia can be defined as painless removal

of a tooth or tooth root from its socket with

minimal injury to the bone and surrounding

structure so that postoperative healing is

uneventful.

Dentistry is one of the fastest growing science of

medicine. With the introduction of many newer

instruments and anesthesia, extraction is a routinely

carried out procedure in dental office. Tooth extraction

remains an essential component of both the art and

science of dentistry despite the enormous progress in

the prevention of dental disease made during the last

three decades of the twentieth century. The effect of

the fluoride revolution and increasing public awareness

of oral health means that people in the western world

are retaining their teeth longer and fewer teeth are being

extracted, particularly in adolescents and young adults.

This trend towards the retention of the natural dentition

into later life is resulting in more extractions being needed

in older patients, who have more complicated medical

history and bone is more brittle than the young. Thus,

the difficulty and complexity of extraction procedures

is increasing with the average age of our patients.

Dental surgeons, especially those in practice, are

required to face these challenges in medico-legal climate

in which litigation exists when complications arise for

whatever reason. It is therefore more important that

the principles and techniques of removing teeth are

understood by all those in the dental profession who

would pick up a pair of extraction forceps.

Having a tooth extracted may also pose a daunting

challenge to patients whose imagination of what is

to happen are often governed by misbeliefs, others

experience and existing social taboos could get the better

of them. Calm, reassuring approach by the dental

surgeon whilst explaining the procedure goes a long

way towards allowing such fears and building their

confidence. The successful outcome of tooth extraction

depends not only on the surgeon's practical skills, but

also on his or her ability to emphasize with patients and

the way they perceive the problem.

The extraction of tooth is a surgical procedure

involving bony and soft tissue of oral cavity, access to

which is restricted by the lips and cheeks and further

complicated by the movement of tongue and mandible.

An additional hazard is that this cavity communicates

with pharynx which in turn opens into larynx and

oesophagus. Further this field of operation is flooded

by saliva and inhabited by the largest number and variety

of microorganisms. Finally it lies close to the vital centres.

It is therefore essential that this aspect of oral surgery

be properly understood judiciously performed and be

based on sound surgical principles as it applies to any

other part of human body. No operation performed

by the dentist is fraught with such great danger to the

patient as those of oral surgery, a large part of which

is the extraction of teeth.

While the great majority of extractions can be done

in the dental office, some patients require hospitalization

for this surgery because of predisposing systemic

conditions which increases the surgical risks.

Dental extraction has always been considered to be

an unpleasant procedure for the patients due to pain

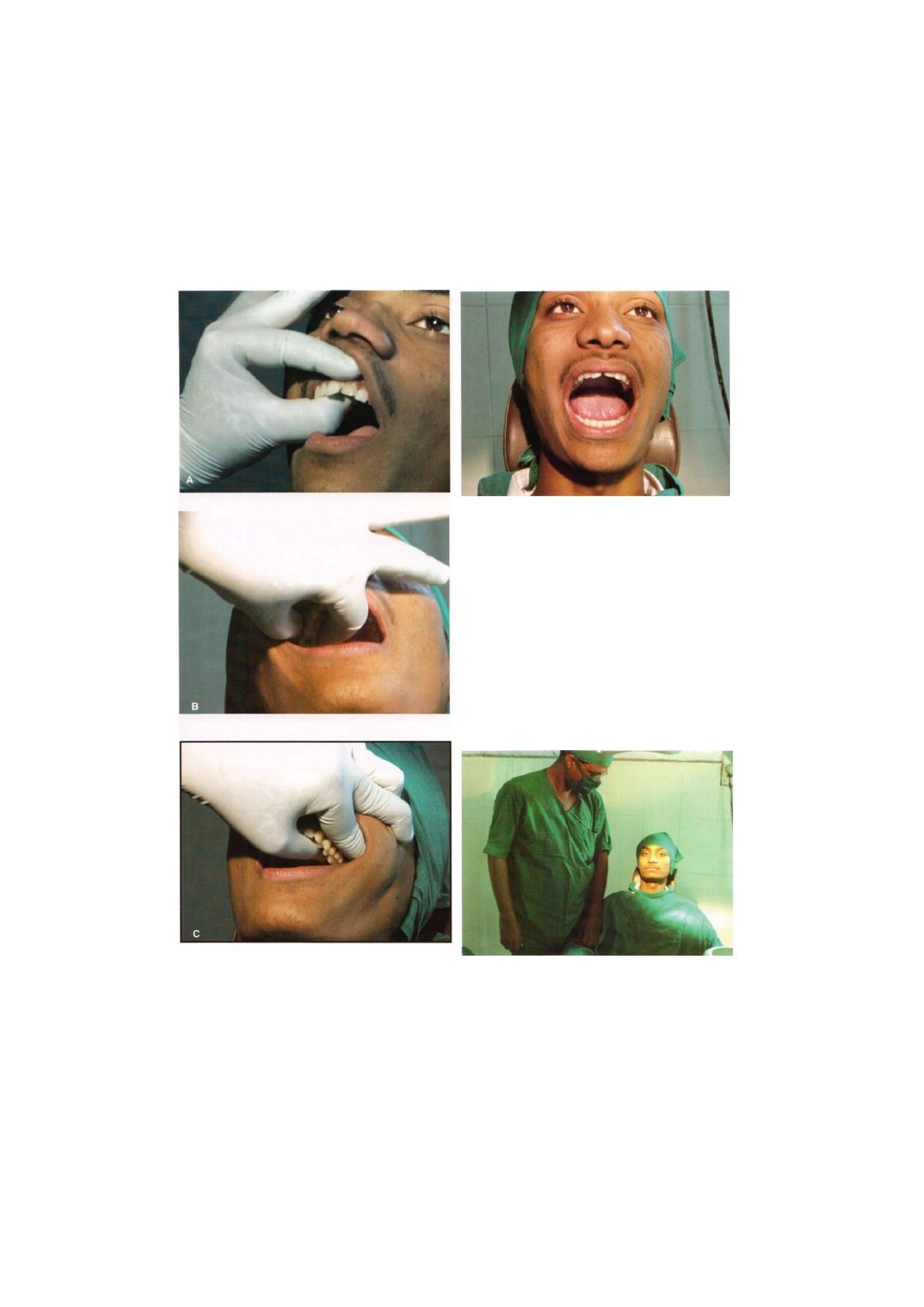

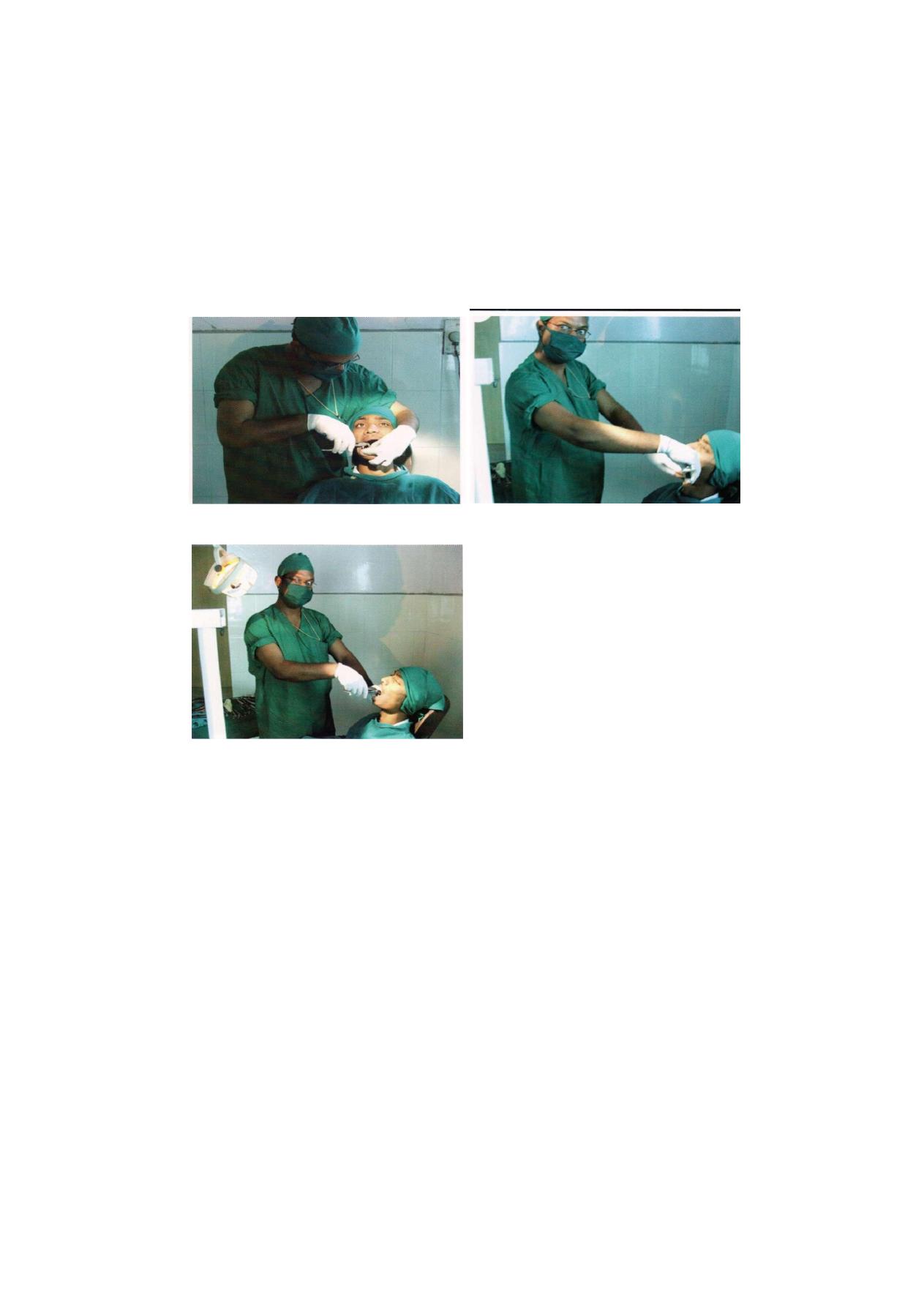

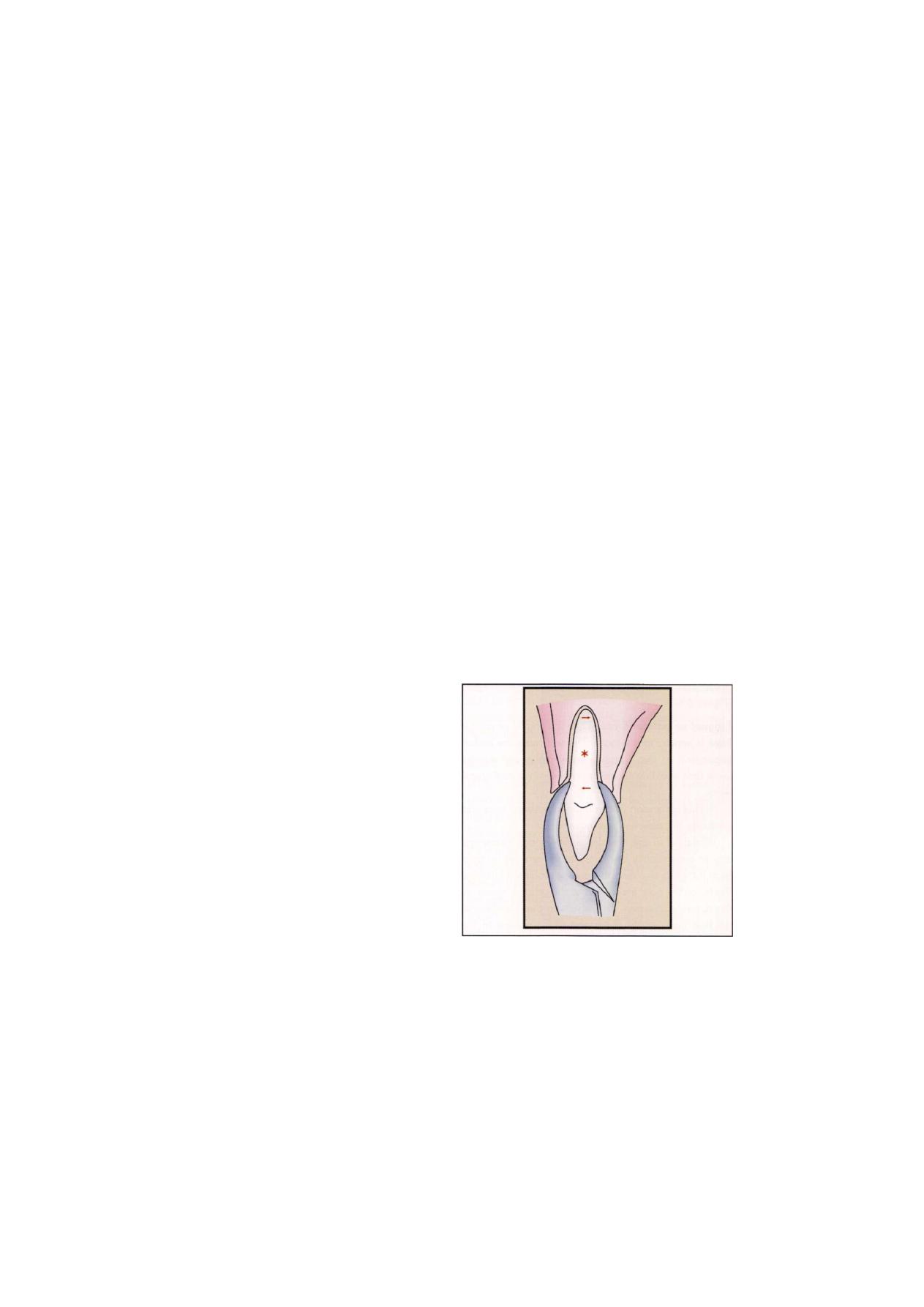

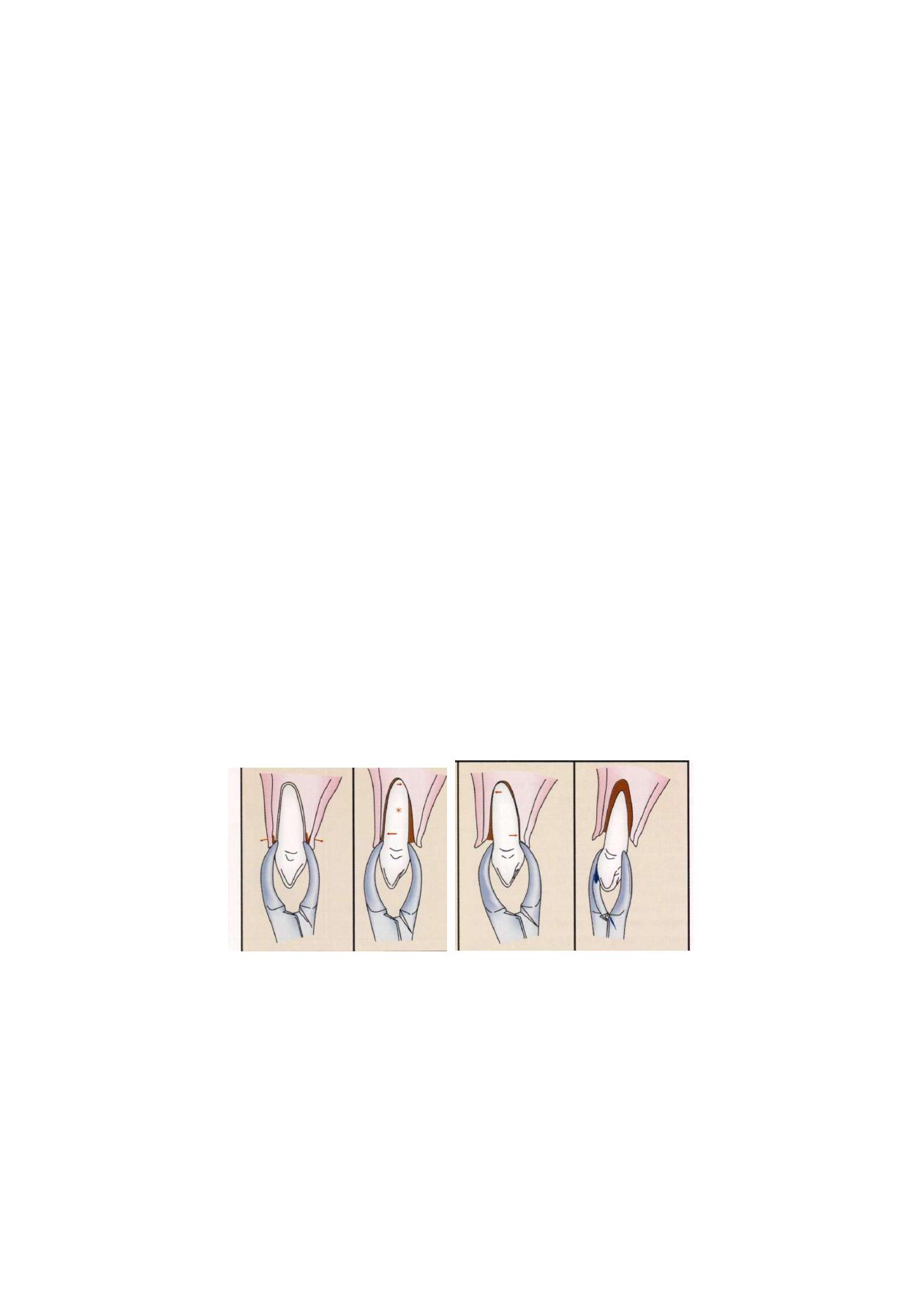

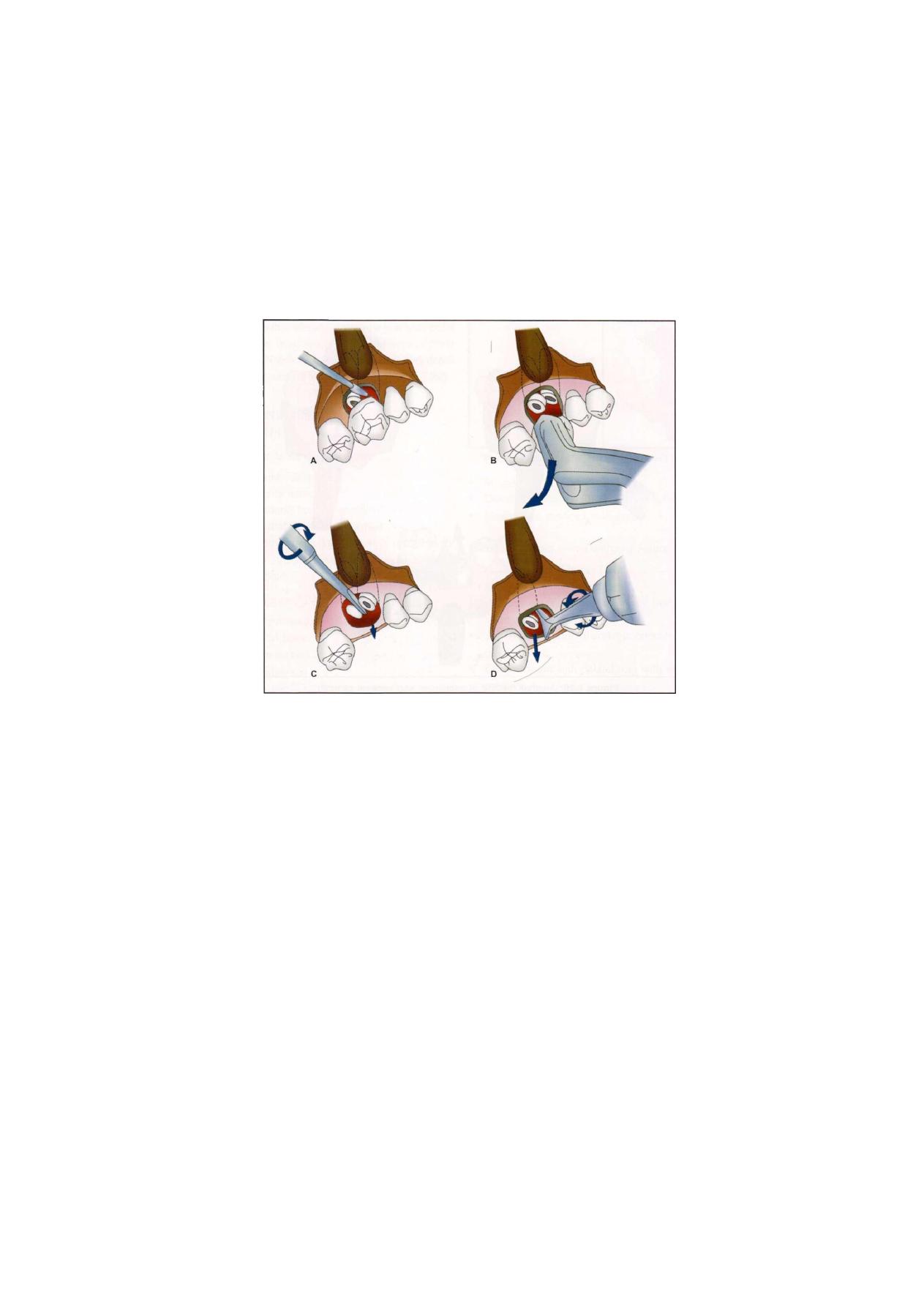

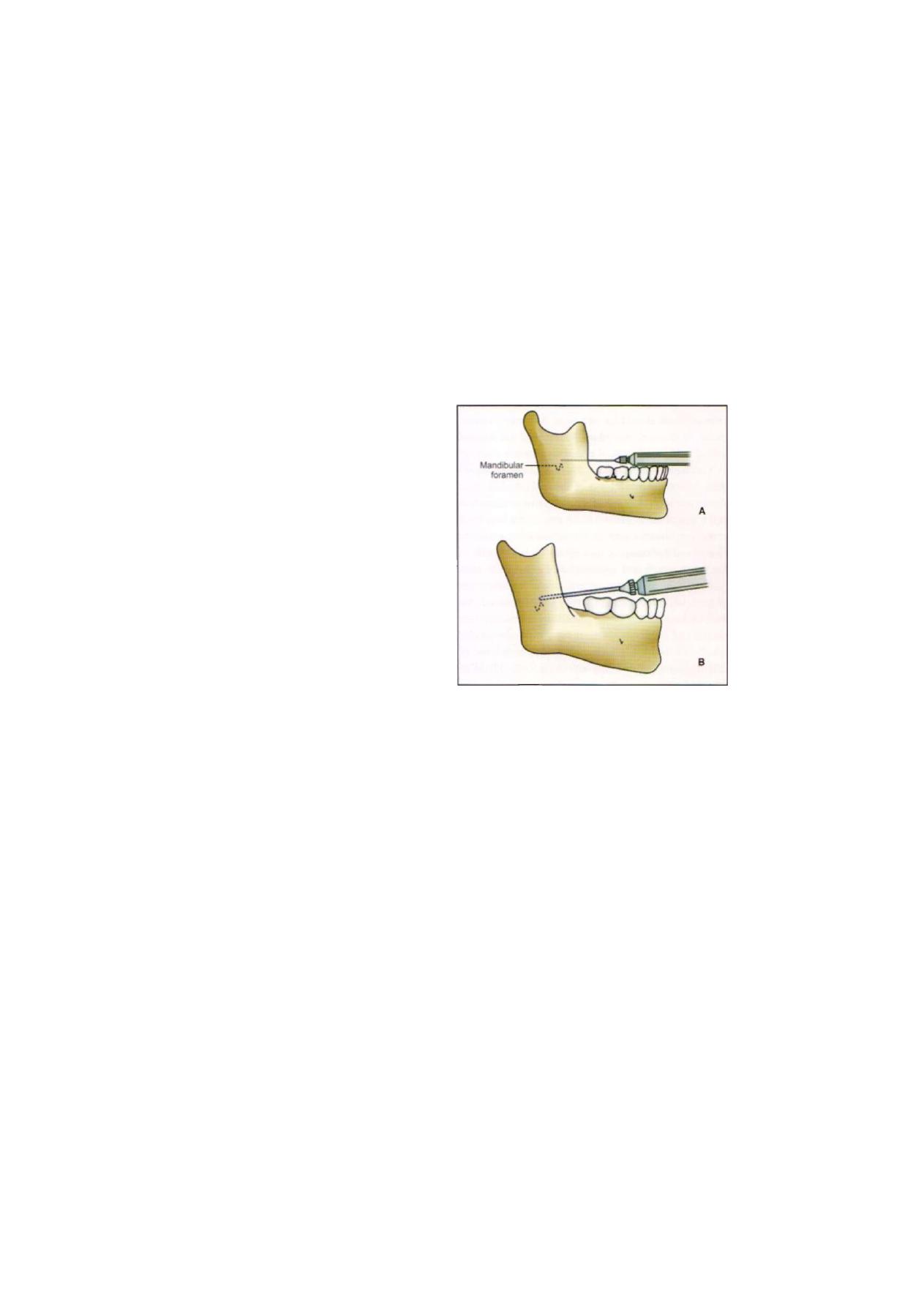

F i g u r e 1.1: Tooth extraction: Traditional method

Introduction

phobia. With the advent of local anesthetic drugs

techniques and standardization of surgical procedure,

extraction is no longer considered to be painful

experience to the patients. Gone are the days when

extraction was supposed to be one of the crude procedure

(Figure 1.1).

The control of the patient is fear and anxiety has

long been a challenge to the dental practitioner. Today's

extraction procedure is painless and anxiety-free provided

that one employs good principles of patient management

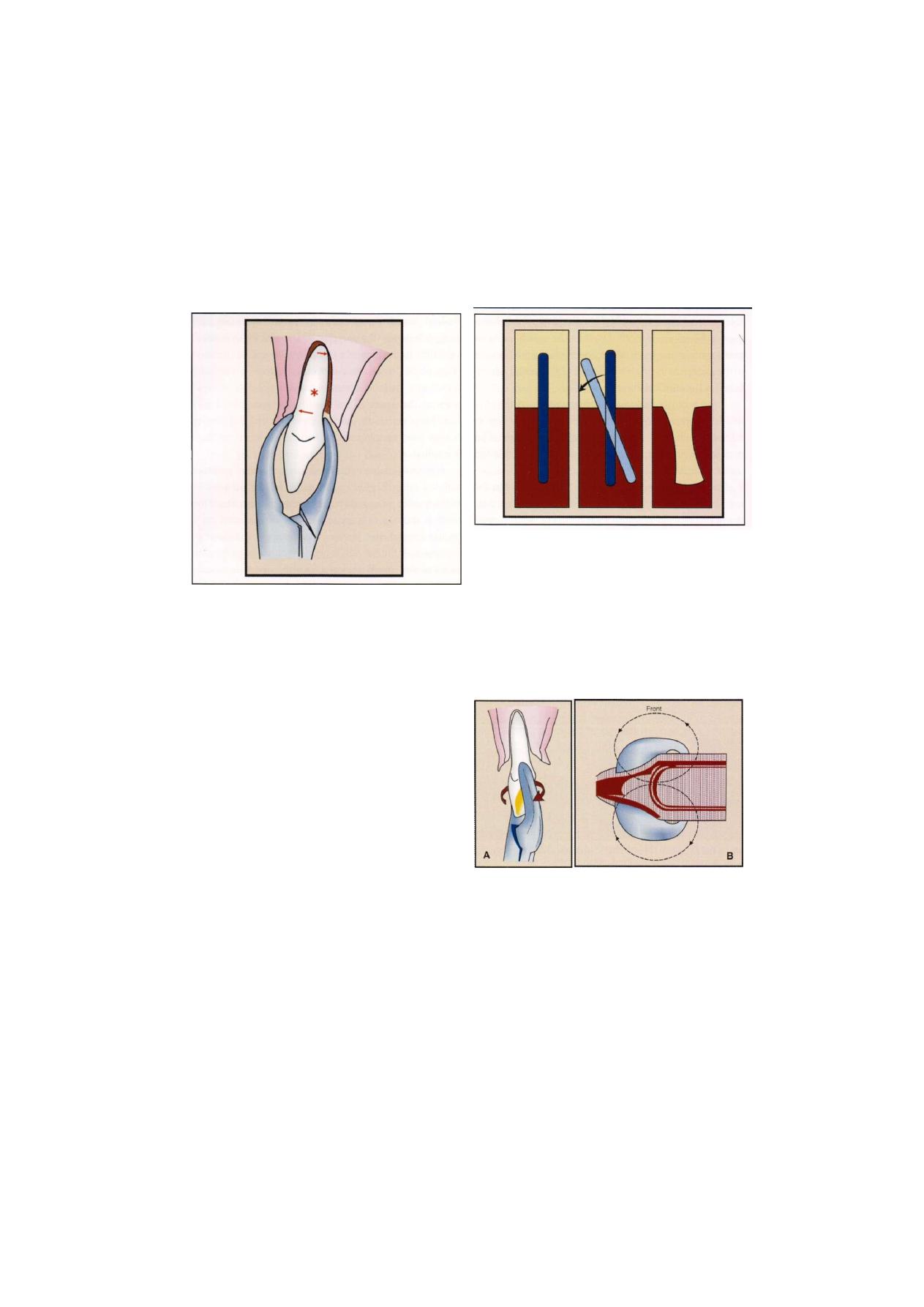

and pharmacokinetics (Figure 1.2).

In the initial few chapters of this book armamentarium

required for tooth extraction, principles of exodontia,

various methods of extraction are described. Then a brief

idea about anatomical considerations and anesthesia

is described. Next few chapters describe special techni-

ques like pediatric extractions serial extractions and

F i g u r e 1.2: Extraction of tooth in dental office

extractions for medically compromised patients. Lastly,

the complications are described in details with their

management.

Armamentarium

6

Exodontia Practice

The purpose of this chapter is to introduce the instru-

ments that are required to perform routine oral surgical

procedures. These instruments are used for a wide variety

of purposes, including both soft tissue and hard tissue

procedures. This chapter deals primarily with a

description of the instruments; subsequent chapters

discuss the actual use of the instruments in the variety

of ways for which they are intended.

INSTRUMENTS USED TO EXTRACT TOOTH

(DENTAL FORCEPS)

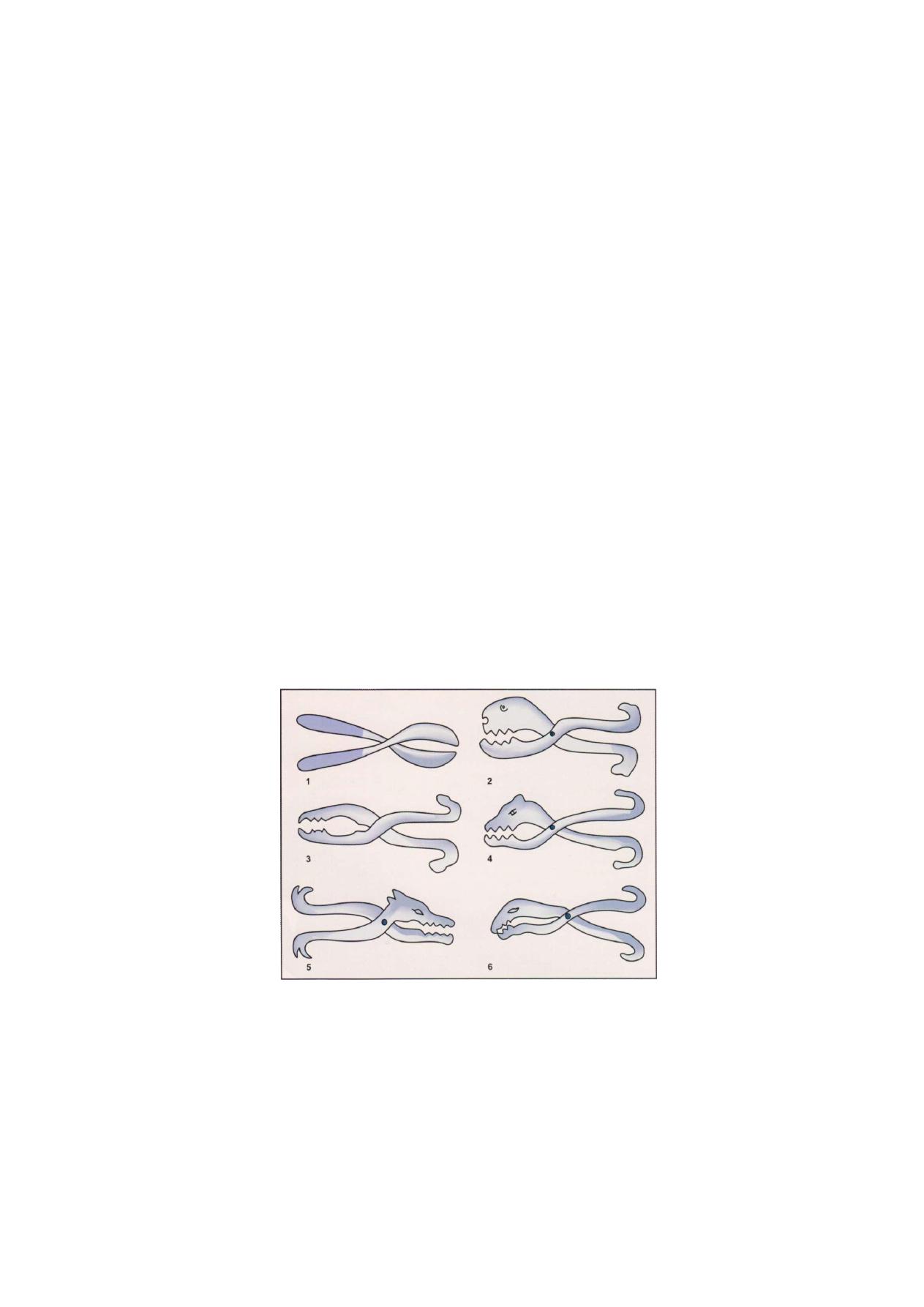

Dental forceps were used in Greek times and were first

illustrated by Albucasis. He described a short handled pairs

which were first applied to the crown of the tooth to shake

it up and then the long handled forceps were used to

complete the extraction. Cyrus Fay in 1826 was first to

describe forceps design to fit the neck of the tooth and

these were said not to apply any force to the crown. The

credit for anatomically designed forceps is frequently given

to Sir John Toms (1841), and there is no doubt his

instruments were superior to those of Fay and it is from

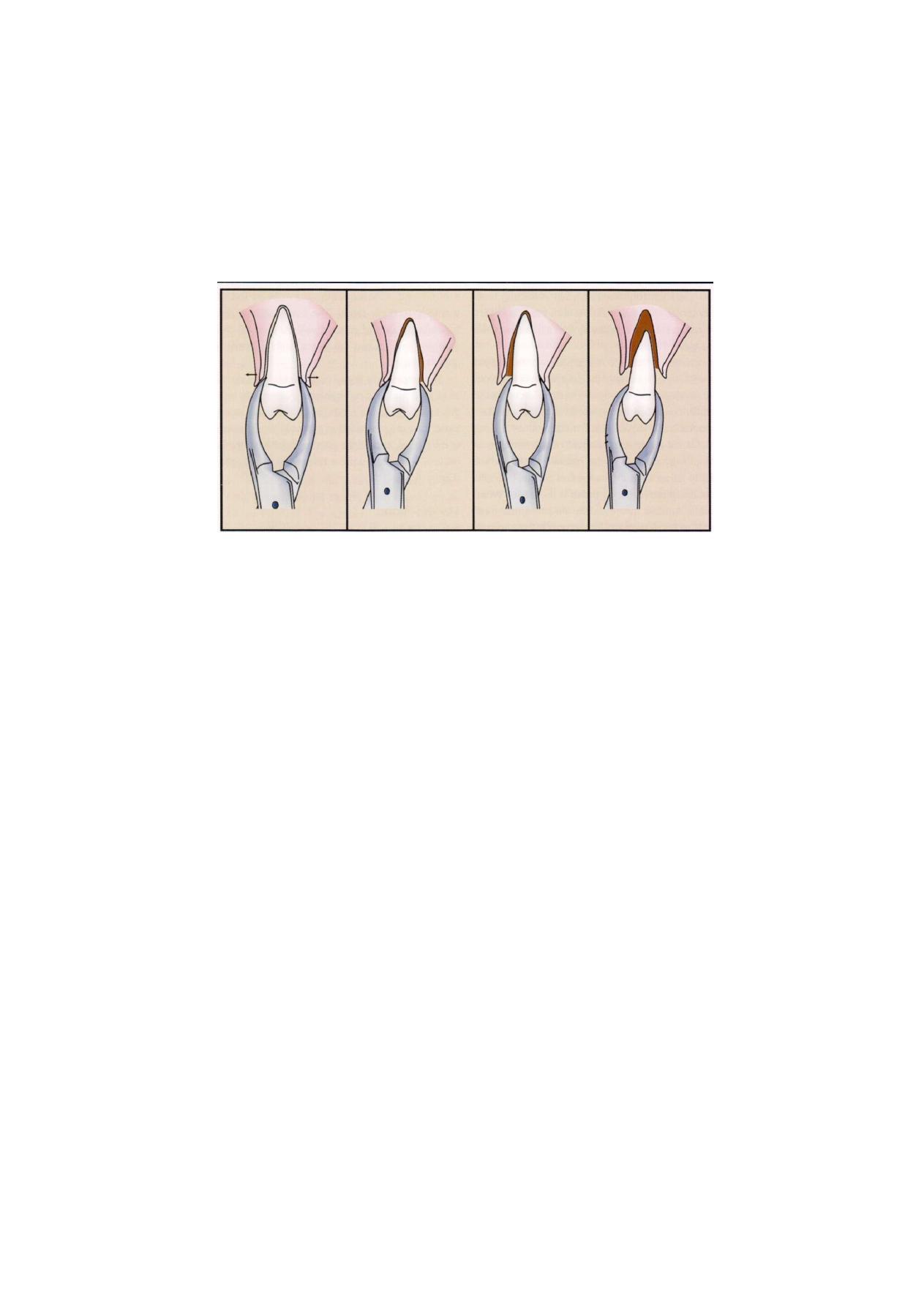

his design modern forceps have developed (Figure 2.1).

The dental forcep is the most widely used instrument

in the extraction of teeth. The use of this instrument makes

it possible for the operator to grasp the root portion of

a tooth and to luxate the latter from its socket by exerting

pressure upon it. The forceps have blades and handles

united by a hinge joint. The larger the ratio between

the length of the handles and the length of the blades

the greater is the force which can be exerted upon the

root. The length of the handle must be such that the

forceps fits the operator hand. Greater the distance

between the hinge joint and operator's hand, the greater

is the movement of the forceps within the hand. Thus,

greater energy may be dissipated to the tooth.

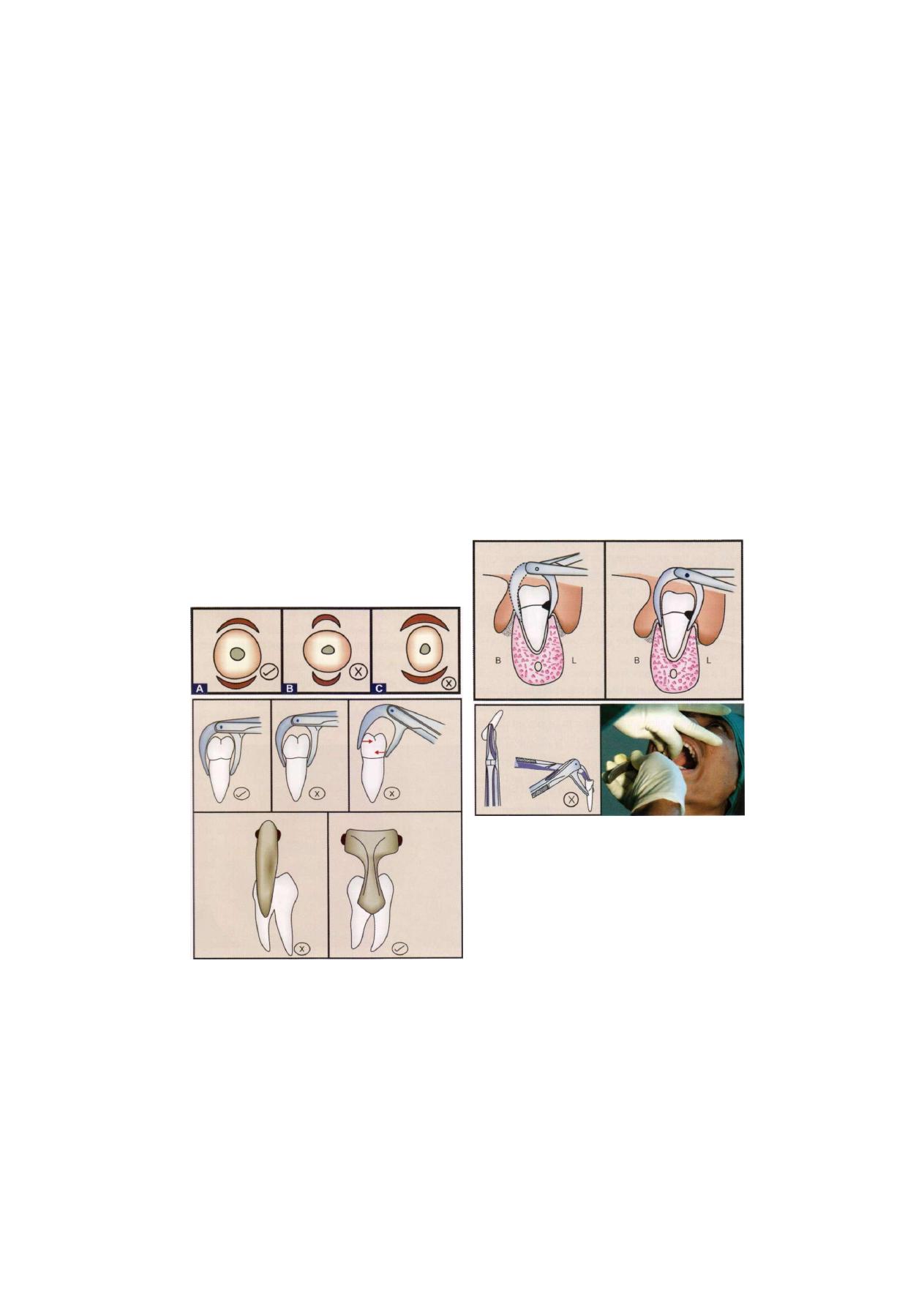

The blades of the forceps are forced into the

periodontal ligaments to separate it from the tooth. Thus,

the blades should be always sharp. The blades of stainless

steel forceps can be sharpened with a sandpaper disk

applied to the outside of the tips.

Ideally the whole of the inner surface of the blade

should fit the root surface. In practice the size and shape

of roots vary so greatly that it is not possible to achieve

this aim and root is grasped by the edges of the blades

F i g u r e 2 . 1 : Dental forceps: Various designs in literature

Armamentarium

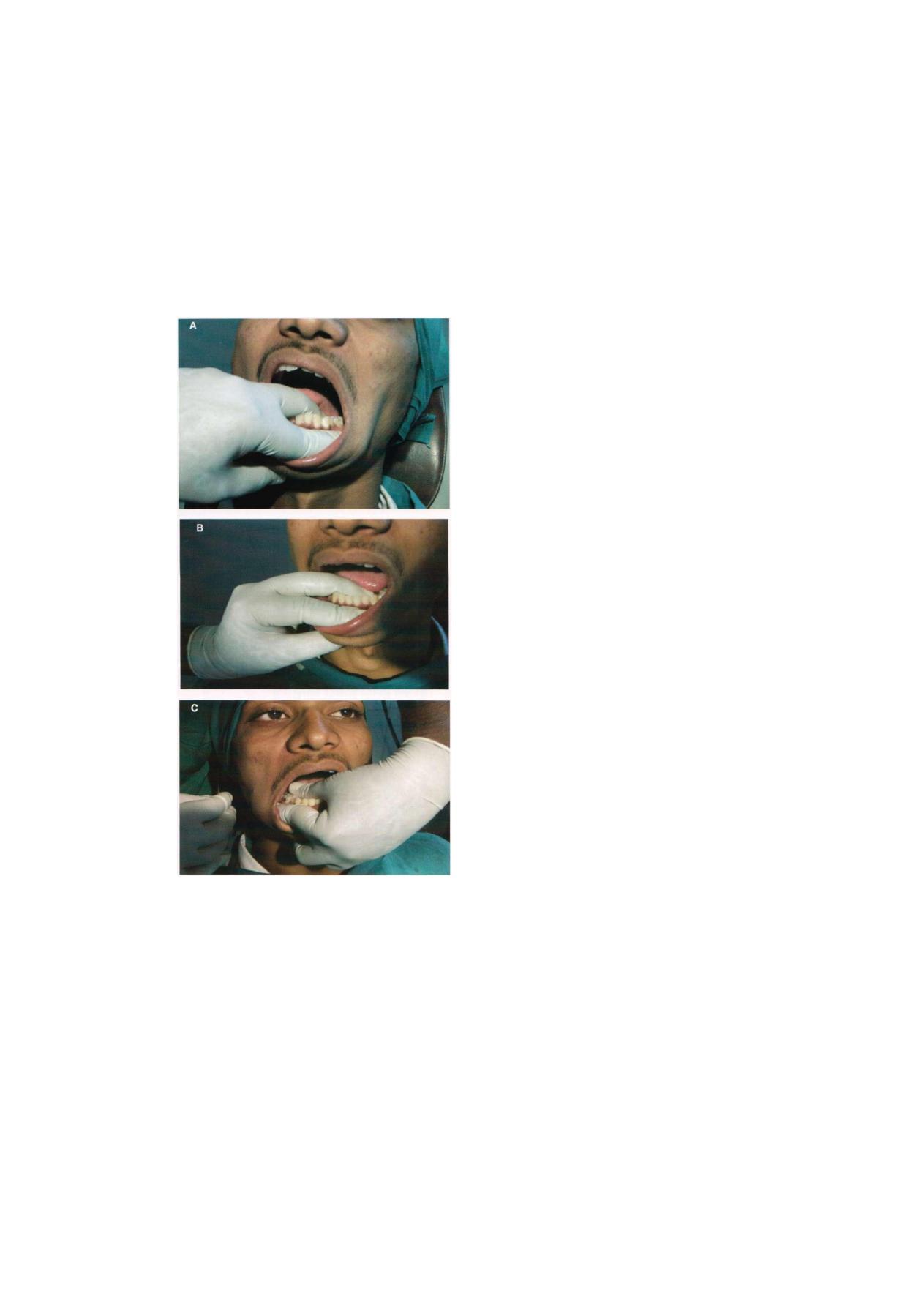

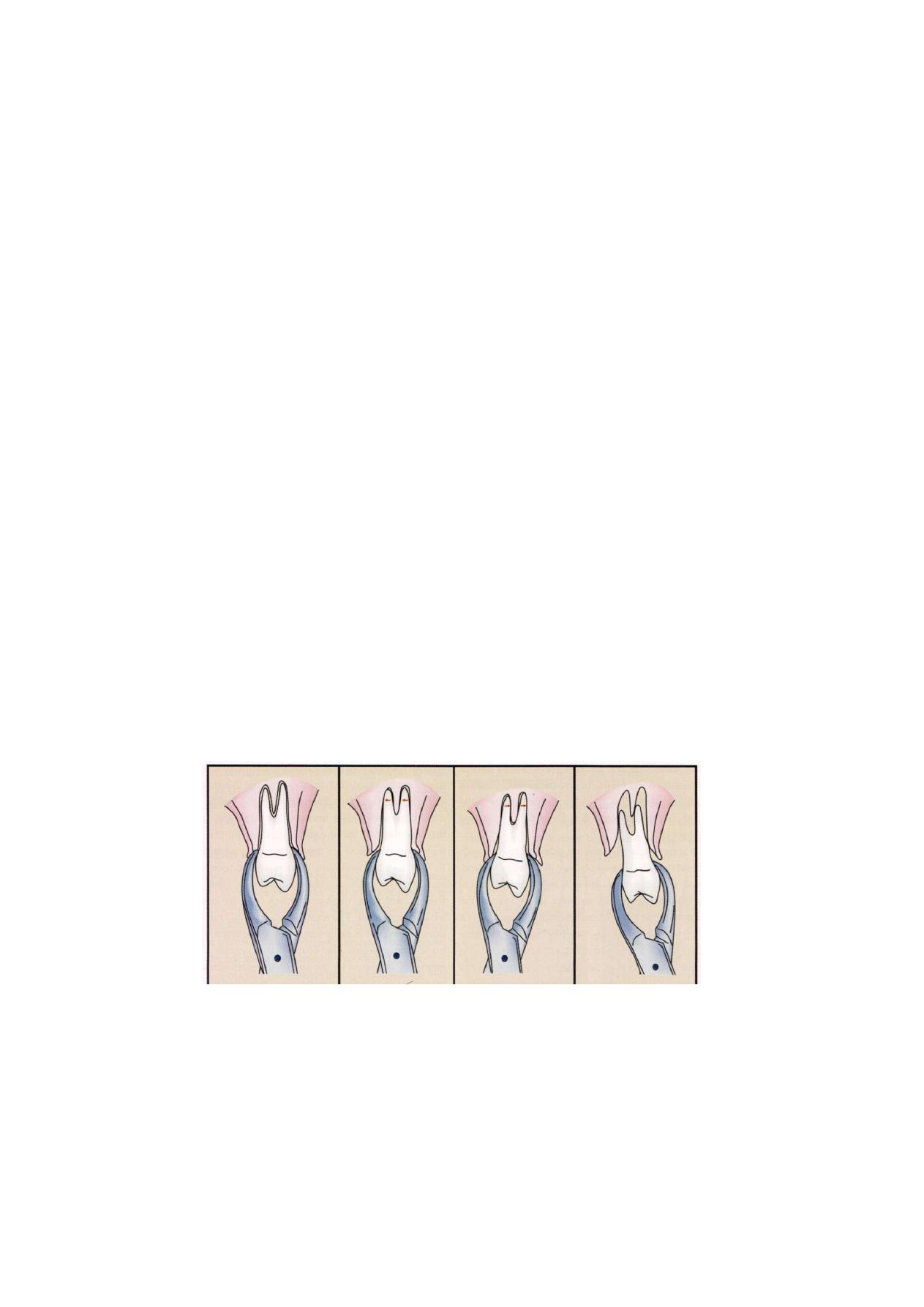

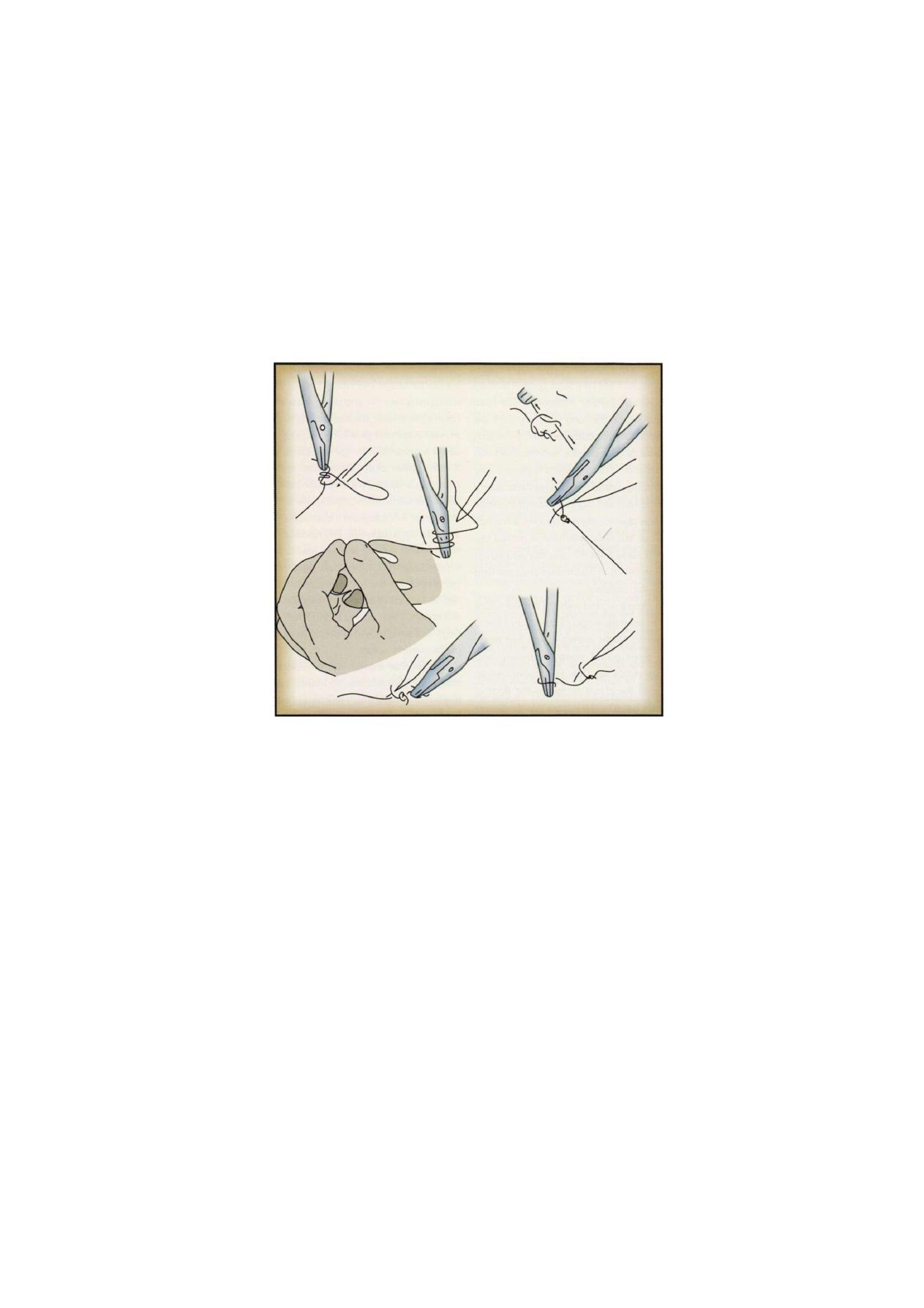

F i g u r e s 2.2A a n d B: Effective use of forceps: (A) Maxillary, (B) Mandibular

establishing a two point contact. If there is a single point

contact between the tooth and blade, the tooth will

probably crushes when it is gripped. It is better to use

forceps with blades which are slightly narrow than a

forceps with blades which are too broad.

The effective use of various instrument depends on

understanding the design of the instruments and their

principles. Forceps permits controlled force application

on the tooth that allows dilatation of alveolar socket,

luxation of tooth and its subsequent removal.

The forceps can be classified as American pattern

of forceps and English pattern of forceps. In the Indian

subcontinent the English pattern is more popular.

The forceps used for the maxillary and mandibular

teeth differ in their design.

In mandibular forceps, the beaks are at right angle

to the long axis of the handle while in maxillary forceps

beaks are in the same line, i.e. parallel to the long axis

of the handle.

The handles of forceps are held differently depending

on the position of tooth to be removed. Maxillary forceps

are held with the palm underneath the forceps. So that

the beak is directed in a superior direction. The forceps

used for the removal of mandibular teeth are hold with

palm on top of the forceps so that beak is pointed down

towards the tooth (Figures 2.2A and B ) .

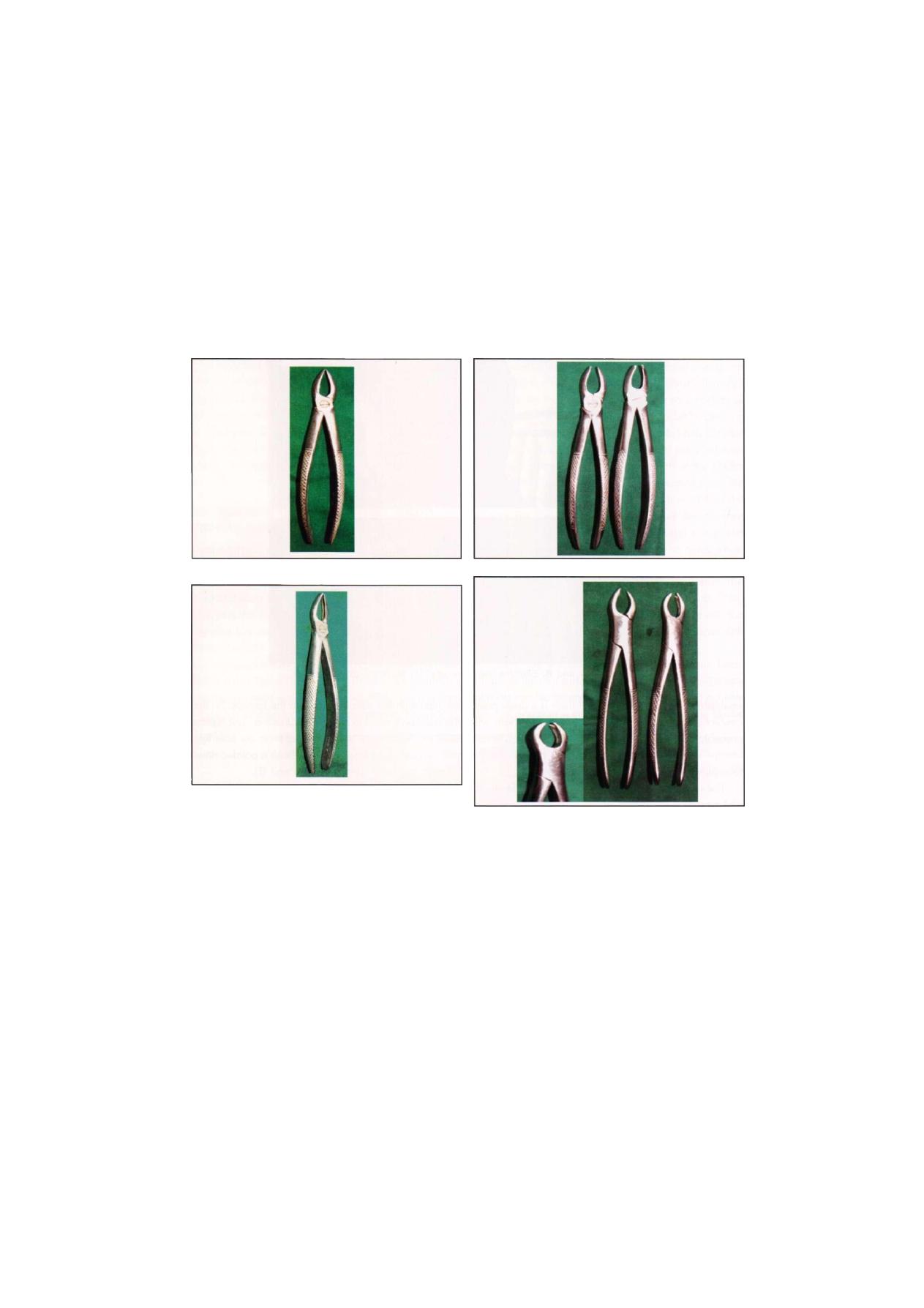

MAXILLARY FORCEPS

Maxillary Anterior Forcep

This forcep has beaks in approximation with each other

and the handle is straight without curvature. Beaks are

symmetrical and are placed in the same line as the

handle. Beaks are shorter than the handle. This forcep

is used for the extraction of maxillary incisors and

canine (Figure 2.3).

Maxillary Premolar Forcep

This forcep is having beaks which are approximating each

other and placed parallel to handle. Handle is having

concavity on one side and convexity on other side (Figure

2.4). This provides better grip and allows the forcep

8

Exodontia Practice

F i g u r e 2.3: Maxillary anterior forcep

F i g u r e 2.4: Maxillary premolar forcep

to reach inside more posterior in oral cavity. This forcep

is used for removal of maxillary premolars and rarely

upper roots.

Maxillary Molar Forcep

These forceps are paired forceps having beaks which

are asymmetrical and broader as compare to anterior

forceps. The one beak is pointed to engage the bifurcation

of the tooth on buccal side and other engages the

palatal root. Depending upon the position of pointed

beak the forceps can be identified as right and left. The

handle is same as that of maxillary premolar forceps

(Figure 2.5).

F i g u r e 2.5: Maxillary molar forceps (right and left)

F i g u r e 2.6: Maxillary cow horn forceps (right and left)

Maxillary Cow Horn Forcep

These are the paired forceps having design same as that

of maxillary molar forceps except they are having beaks

that appear as the horn of the cow and called as cow

horn forceps. One beak is pointed which goes in buccal

bifurcation other beak is having notch which engages

the palatal root. These are paired forceps used for right

and left side separately (Figure 2.6). They are used for

maxillary molars which are badly carious in nature. The

major disadvantage is that they crush alveolar bone when

used on intact teeth.

Armamentarium

F i g u r e 2.7: Maxillary bayonet forcep Figure 2.8: Maxillary third molar forcep

Maxillary Bayonet Forcep

This forcep is designed for removal of maxillary roots.

Beaks are symmetrical and closely approximate to each

other. The beaks are narrow to fit it to the circumference

of the root (Figure 2.7). Handle is having angulations

so that it can reach as much posteriorly as possible.

Maxillary Third Molar Forcep

This forcep is specially designed for removal of maxillary

third molar. The forceps have beaks which engage the

crown of third molar and is having long handle to reach

the posterior most region in maxilla (Figure 2.8).

MANDIBULAR FORCEPS

Mandibular Anterior Forcep

This forcep is having beaks similar to maxillary incisor

forcep which approximate with each other. Beaks are

at right angle to the handles. This forcep is used for

extraction of mandibular incisor and canine (Figure 2.9).

F i g u r e 2.9: Mandibular anterior forcep

Mandibular Premolar Forcep

This forcep has same design as that of mandibular

anterior forcep except the space in between two beaks

is more compared to incisor forcep to accommodate the

crowns of premolar which are having greater diameter

(Figure 2.10).

Mandibular Molar Forcep

These are unpaired forceps having beaks broader and

stout. The beaks are symmetrically pointed so that sharp

pointed tips can engage the bifurcation both at buccal

and lingual surfaces. The beaks are at right angles to

the handle. These forceps are used for the extraction

of mandibular molars (Figure 2.11).

10

Exodontia Practice

F i g u r e 2.10: Mandibular premolar forceps

F i g u r e 2 . 1 1 : Mandibular molar forceps

Mandibular Cow Horn Forceps

The design of this forcep is same as that of mandibular

molar forcep except the beaks are pointed and conical

in shape. These forceps are used for the extraction of

mandibular molars.

Universal Forcep

This forcep is having the beaks similar to the mandibular

molar forcep except that they are facing forward towards

each other at right angle to the handle. This is a specially

designed forcep mainly used for extraction of third molars

(Figure 2.12).

INSTRUMENTS USED FOR TOOTH LUXATION

(ELEVATORS)

Elevators are the instruments used to elevate the tooth

or root from the alveolar socket. Elevation of tooth before

application of forcep makes a difficult extraction easy.

The elevators are designed on two basic patterns. In

general all the elevators have handle, shank and a blade.

In the straight pattern all these three components are

Figure 2.12: Universal forceps

placed in one plane. In the other design the blade and

shank are in one plane and handle is placed at right

angle to them. There are so many elevators available

commercially but a few are widely used because of their

efficiency and convenience.

The elevators deliver the force based on various

mechanical principles to drive the tooth or root along

its path of delivery or line of withdrawal. It represents

the direction along which the tooth move out of the

alveolar socket with economy of force and economy of

instrumentation. Hence, successful use of an elevator

depends on the determination of the convenient path

of its delivery. Principles of use of elevators are described

in the principles of exodontia chapter.

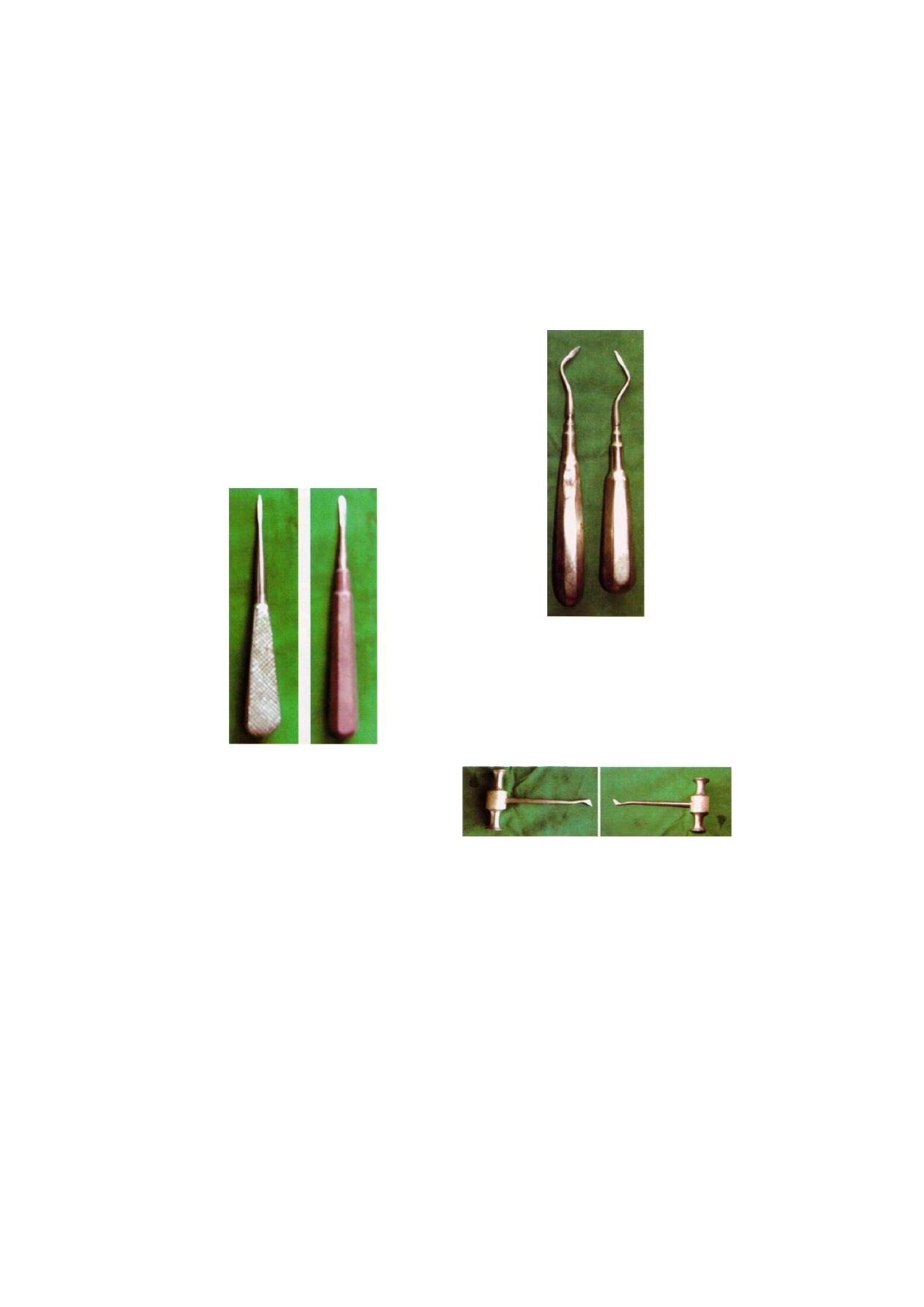

TYPES

The elevators which are widely used in the dental practice

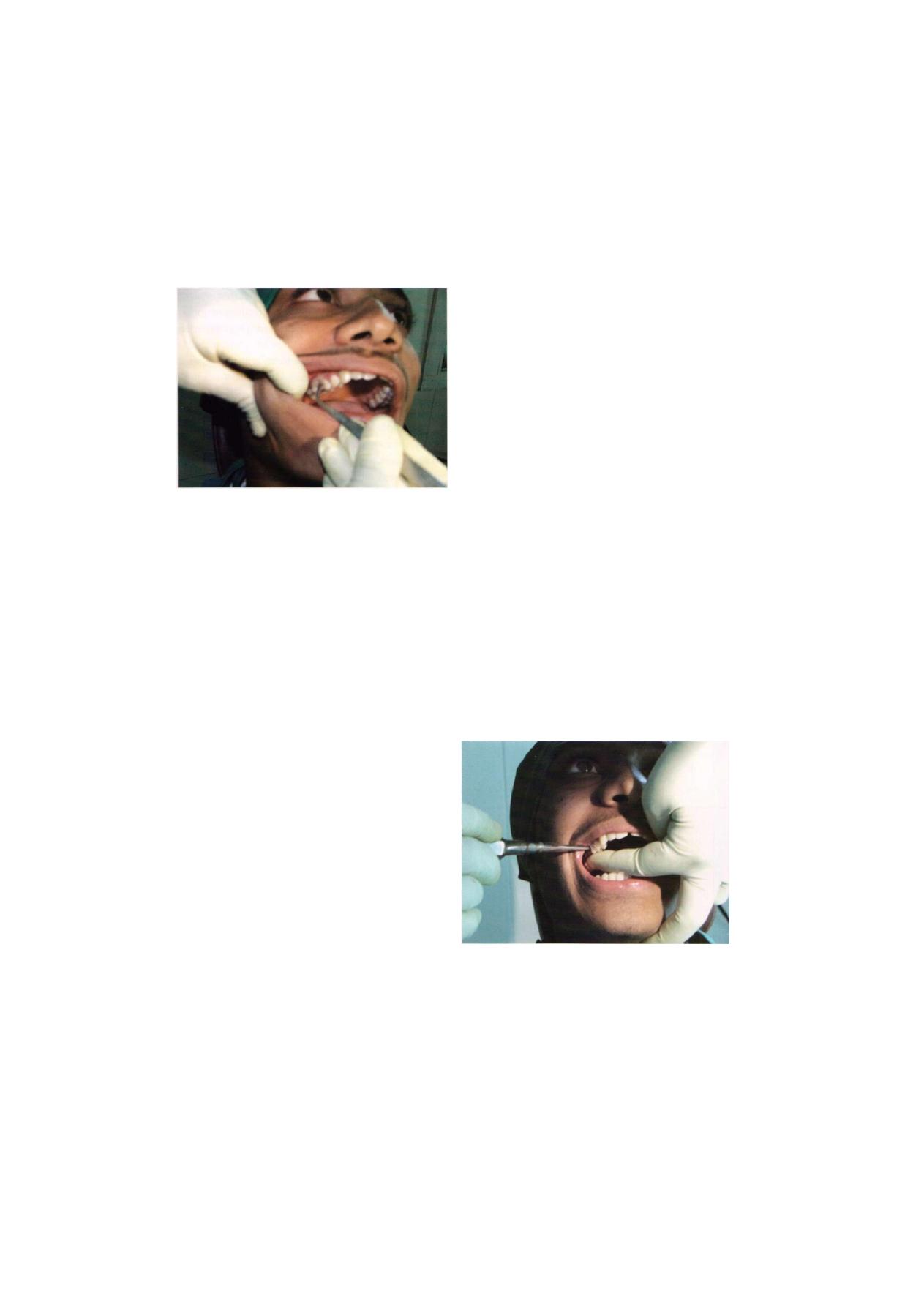

are (Figure 2.13):

1. Straight elevator

2. Apexo elevator (Right and left)

3. Cross bar elevator

F i g u r e 2.13: Different types of elevators. (A,B) Straight

elevator, (C) Apexo elevator, (D) Cross bar elevator

11

Armamentarium

Straight Elevator

The blade, handle and shaft are in one line. The blade

is pointed or broad and bluff as in coupland elevator.

The blade is having concave surface on one side, so

that it can be used in same fashion as shoehorn.

The elevator is used to elevate the mandibular and

maxillary molars to luxate the teeth in case of multiple

extraction. It is usually avoided in anterior teeth (Figure

2.14).

B

F i g u r e 2.14: Straight elevators. A—Straight pattern, B—

Coupland pattern

Apexo Elevator

These elevators are paired having handle, shank and

blade which are in same plane. The blade is having

angulations so that it reaches the root apices. This elevator

works on the principle of wedge (Figure 2.15).

Cross Bar Elevator

These are paired elevators having blade and shank at

right angle and shank and handle at right angle to each

other. This is indicated for the removal of the mandibular

roots where the other root has already been removed.

In such cases the tip of the elevator is introduced to the

depth of the empty socket with the concave surface of

F i g u r e 2.15: Apexo elevator (Paired elevators)

the elevator facing the root to remove. By applying wheel

and axle principle with rotatory movement, the inter-

radicular septum and the root are elevated out of alveolar

socket. The same elevator is used for elevating the distal

root on the right side and the mesial root on the left

side (Figure 2.16).

F i g u r e 2.16: Cross bar elevators (Paired elevators)

Winter Cryer Elevator

This elevator is same as that of cross bar except handle

is parallel to the working end. This is a set of elevators

used for removal of root apices (Figure 2.17).

Axio Elevator

These are specially designed elevators which are used

for elevation of mandibular third molars (Figure 2.18).

12

Exodontia Practice

F i g u r e 2.17: Winter crayer elevator (Paired elevators)

F i g u r e 2.18: Axio elevator (Paired elevators)

INSTRUMENTS TO INCISE TISSUE

Most surgical procedures begin with an incision. The

instrument for making an incision is the scalpel, which

is composed of a handle and sharp blade. The most com-

monly used handle is the No. 3 handle, but occasionally

the longer, more slender No. 7 handle is used. The tip

of the scalpel handle is prepared to receive a variety of

differently shaped scalpel blades that can be inserted onto

a slotted receiver (Figure 2.19).

The most commonly used scalpel blade for intraoral

surgery is the No. 15 blade. It is relatively small and can

F i g u r e 2.19: Scalpels for making incision

(BP handle No. 3 and No.

7)

be used to make incisions around teeth and through

mucoperiosteum. It is similar in shape to the large

No. 10 blade, which is used for skin incisions. Other

commonly used blades for intraoral surgery are the'

No. 11 and the No. 12 blades. The No. 11 blade is

sharp pointed blade that is used for making stab incisions,

such as for incising an abscess. The hooked No. 12 blade

is useful for mucogingival surgery procedures where

incisions must be made on the posterior aspect of teeth.

The bard parker handle is of different number, i.e.

No. 3 handle is used to receive blades No. 15, No. 11,

No. 12, and No. 4 handle is used to receive No. 10

blade (Figure 2.20).

F i g u r e 2.20: Different types of blades. BP handle blade

The scalpel blade is carefully loaded onto the handle

with a needle holder to avoid lacerating the operator's

fingers. The blade is held on the superior edge where

it is reinforced with a small rib, and the handle is held

so that the male portion of the fitting is pointing upward.

The blade is then slid onto the handle until it clicks into

position. The knife is unloaded in a similar fashion. The

needle holder grasps the most proximal end of the blade

Armamentarium

F i g u r e 2 . 2 1 : Loading and unloading of scalpel blades

and lifts it to disengage it from the male fitting. It is then

slid off the knife handle in the opposite direction. The

used blade is discarded into a proper container (Figure

2.21).

When using the scalpel to make an incision, the

surgeon holds it in the pen grasp to allow maximal con-

trol of the blade as the incision is made. Mobile tissue

should be held firmly to stabilize it so that as the incision

is made, the blade will incise, not displace, the mucosa.

Whole length of the blade must be drawn for incising

tissue. If only one end is used cutting is inefficient and

uncontrolled. When a mucoperiosteal incision is made,

the knife should be pressed down firmly so that the

incision penetrates the mucosa and periosteum with the

same stroke. Other principles of mucoperiosteal incision

and flap design are described in subsequent chapters.

Scalpel blades are designed for single patient usage.

They are dulled very easily when they come into contact

with hard tissue such as bone and teeth. If several inci-

sions through mucoperiosteum to bone are required,

it may be necessary to use a second blade during a

single operation. It is important to remember that dull

blades do not make clean, sharp incisions in soft tissue

and therefore should never be used.

INSTRUMENTS FOR ELEVATING

MUCOPERIOSTEUM

After an incision through mucoperiosteum has been

made, the mucosa and periosteum should be reflected

from the underlying bone in a single layer with a

periosteal elevator (Figure 2.22). The instrument that is

most commonly used is the Molt periosteal elevator. This

instrument has a sharp, pointed end and a broader flat

end. The pointed end is used to confirm the depth of

incision and reflect dental papillae form between teeth,

The broad end is used for elevating the tissue from the

bone.

F i g u r e 2.22: Periosteal elevators

The periosteal elevator can be used to reflect soft

tissue by three methods. First, the pointed end can be

used in a prying motion to elevate soft tissue. This is

most commonly used when elevating a dental papilla

form between teeth. Second is the push stroke in which

14

Exodontia Practice

the broad end of the instrument is slid underneath the

flap, separating the periosteum from the underlying bone.

This is the most efficient stroke and results in the cleanest

reflection of the periosteum. The third method is a pull

stroke or scrape stroke. This is occasionally useful in some

areas but tends to tear the periosteum unless it is done

carefully.

The periosteal elevator can also be used as a retractor.

Once the periosteum has been elevated, the broad

blade of the periosteal elevator is pressed against the

bone with the mucoperiosteal flap elevated into its

reflected position.

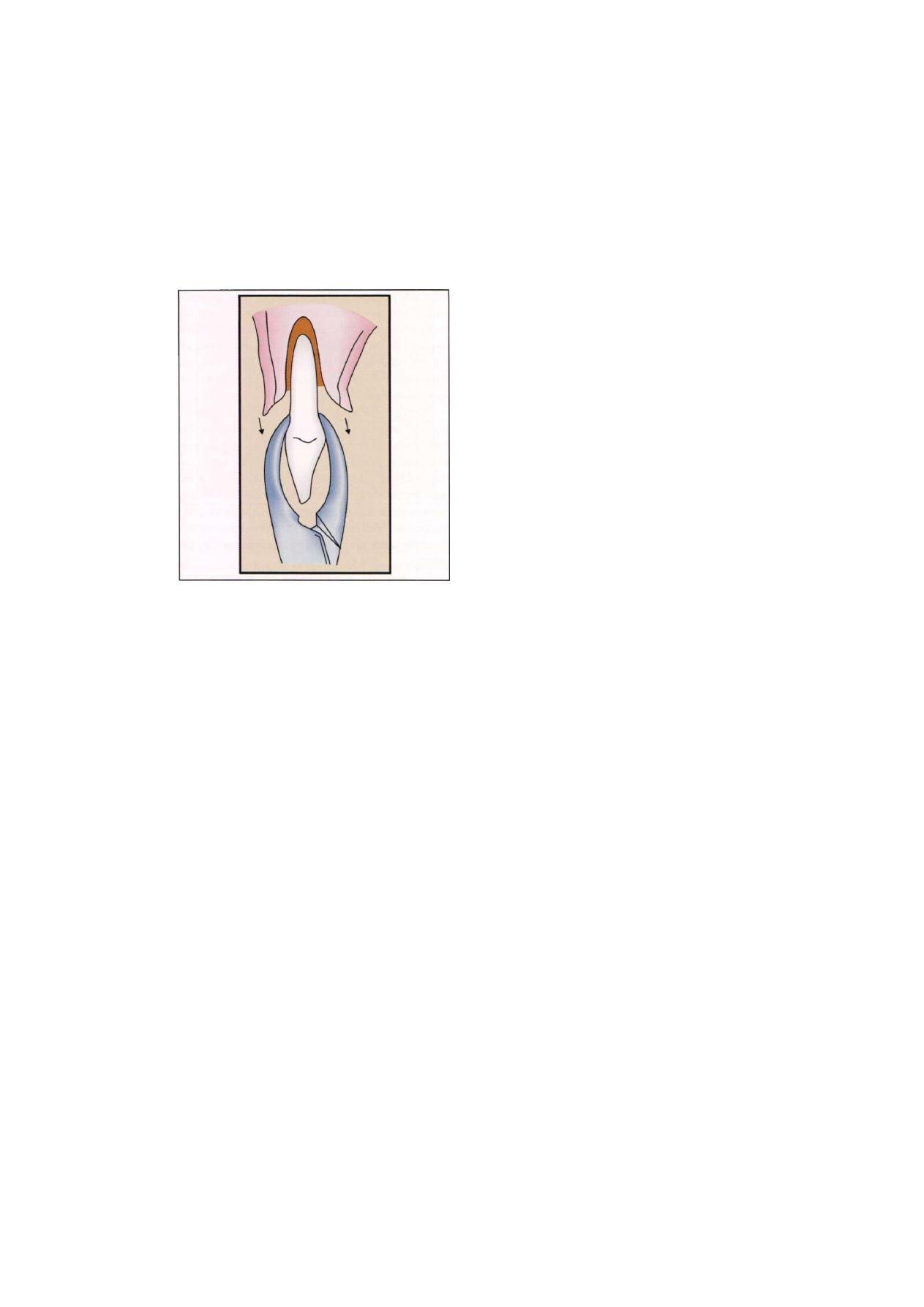

When teeth are to be extracted, the soft tissue attach-

ment around the tooth needs to be released from the

tooth. The instrument most commonly used for this is

the moons probe. This instrument is relatively small and

delicate and can be used to loosen the soft tissue via

the gingival sulcus (Figure 2.23).

F i g u r e 2.23: Moon's probe

INSTRUMENTS FOR CONTROLLING

HEMORRHAGE

When incisions are made through tissue, small arteries

and veins are incised, causing bleeding that may require

more than simple pressure to control. When this is neces-

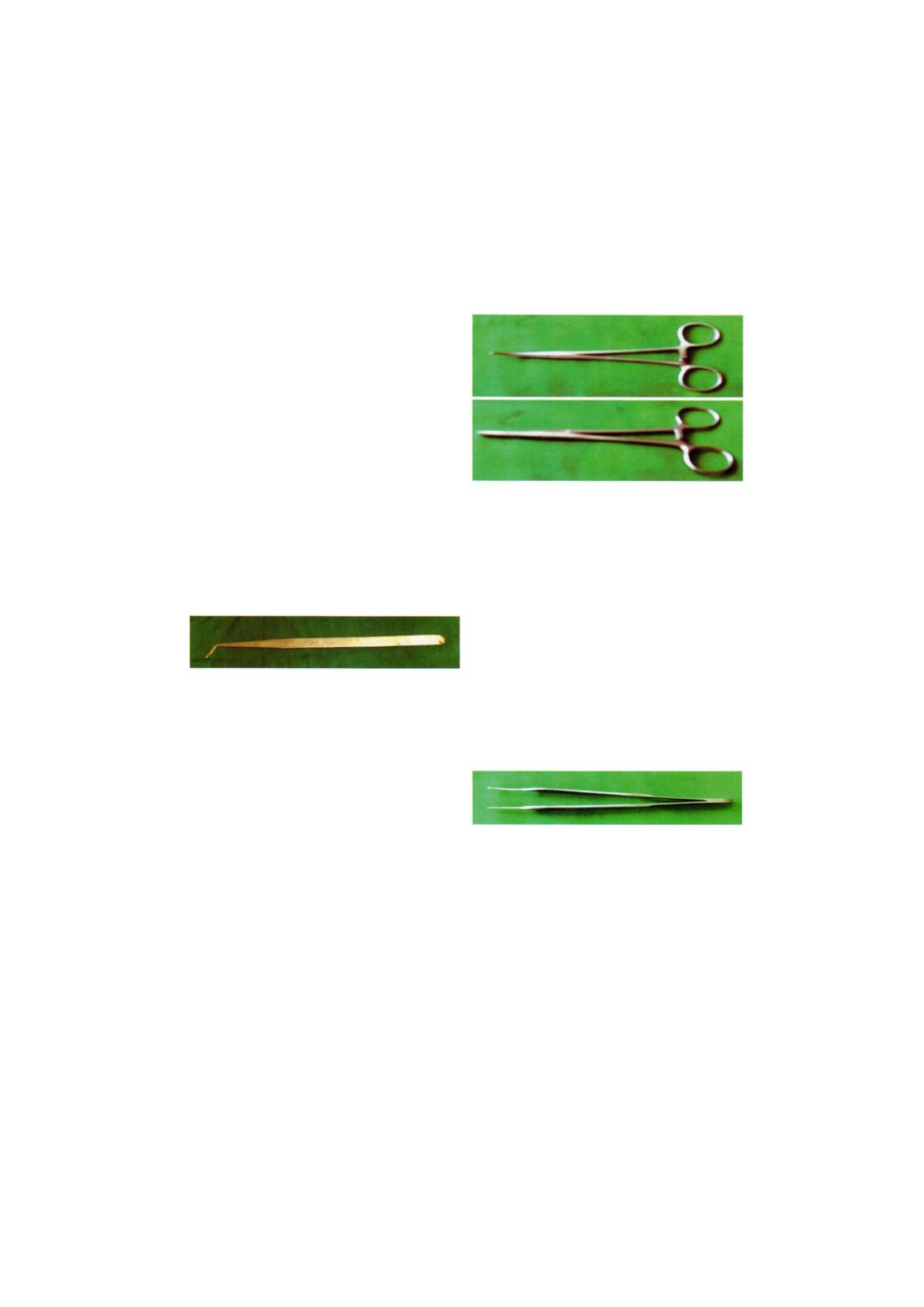

sary, an instrument called a hemostat is used. Hemostats

come in a variety of shapes, may be relatively small and

delicate or larger, and are either straight or curved. The

hemostat most commonly used in oral surgery is a curved

hemostat (Figure 2.24).

A g o o d hemostat must have tips that opposes

accurately with each other. Blades must be closed firmly

on first ratchet and light should not pass through the

blades when handle is fully closed. Hemostat gets spoiled

if hard and bulky material is caught with it. Method of

application of hemostat includes visualization of bleeding

point, application of hemostat at right angle direction

to direction of force of blood. Catch the tip with

Figure 2.24: Hemostats (curved and straight artery forceps)

minimum amount of surrounding tissue as bulky ligation

may slip. In addition to its use as an instrument for

controlling bleeding, the hemostat is especially useful

in oral surgery to remove granulation tissue from tooth

sockets as well as to pick up small root tips from tooth

sockets.

INSTRUMENTS TO GRASP TISSUE

In performing soft tissue surgery, it is frequently neces-

sary to stabilize soft tissue flaps in order to pass a suture

needle. Tissue forceps most commonly used for this

purpose is the Adson forceps. These are delicate forceps

with small teeth that can be used to gently hold tissue

and thereby stabilize it. Adson forceps are also available

without teeth (Figure 2.25A).

F i g u r e 2.25A: Adson forcep

In some types of surgery, especially when removing

larger amount of fibrous tissue as in an epulis fissuratum

forceps with locking handles and teeth that will grip the

tissue firmly are necessary. In this situation Ellis forceps

are used. The locking handle allows the forceps to be

placed in the proper position and then to be held by

an assistant to provide the necessary tension for proper

dissection of the tissue. The Ellis forceps should never

be used on tissue that is to be left in the mouth because

Armamentarium

15

they cause a relatively large amount of crushing injury.

The Ellis forceps are most commonly used instrument

having straight blades and tip slightly curved or angulated

for better grip. Tip is provided with interlocking teeth.

They are three to four in number and interlock with each

other (Figure 2.25B).

F i g u r e 2.25B: Ellis forcep

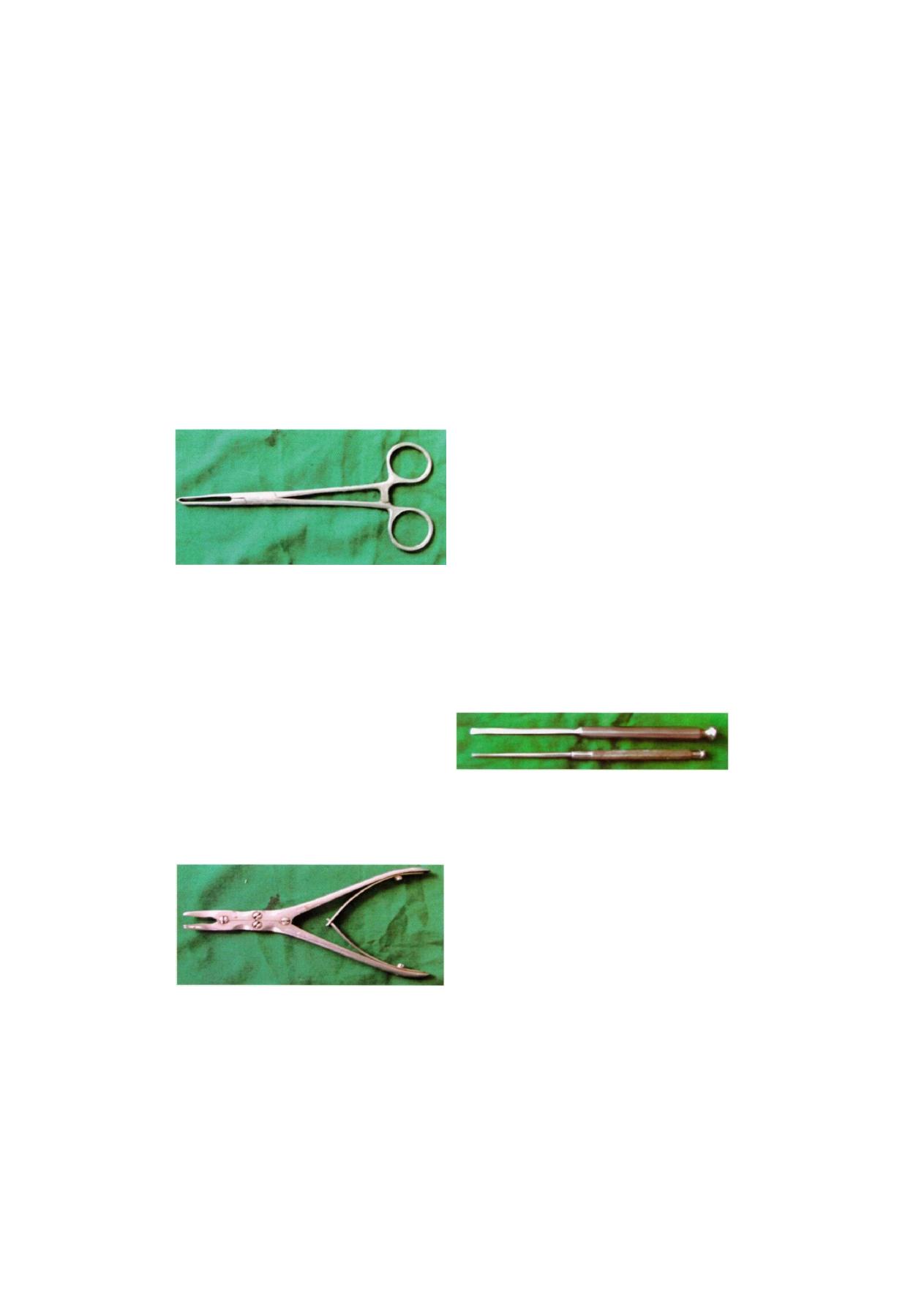

INSTRUMENTS FOR REMOVING BONE

RONGEUR FORCEPS

The instrument most commonly used for removing bone

is the rongeur forceps. These instruments have sharp

blades that are squeezed together by the handles cutting

or pinching though the bone. Rongeur forceps have a

spring between the handle so that when hand pressure

is released the instrument will open. This allows the

surgeon to make repeated cuts of bone without making

special efforts to open the instrument. There are two

major designs for rongeur forceps, a side-cutting forceps,

end-cutting forceps (Figure 2.26).

The end-cutting forceps are more practical for most

dentoalveolar surgical procedures that require bone

removal. These forceps can be inserted into sockets for

F i g u r e 2.26: Rongeur forcep

removal of inter-radicular bone. They can also be used

to remove sharp edges of bone. Rongeurs can be used

to remove large amounts of bone efficiently and quickly.

Because rongeurs are relatively delicate instrument, the

surgeon should not use the forceps to remove large

amounts of bone in single bites. Rather, smaller amounts

of bone should be removed in each of multiple bites.

Likewise, the rongeurs should not be used to remove

teeth, since this practice will quickly dull and destroy the

instrument. Rongeurs are usually quite expensive so care

should be taken to keep them in working order.

CHISEL AND MALLET

One of the obvious methods of bone removal is to use

a surgical chisel and mallet. Bone is usually removed

with a mono bevel chisel, and teeth are usually sectioned

with a bi-bevel chisel. The success of chisel use depends

on the sharpness of the instrument. Therefore, it is

necessary to sharpen the chisel before it is sterilized for

the next patient. Some chisels have carbide tips and can

be used more than once between sharpening. A mallet

with a nylon facing imparts less shock to the patient,

is less noisy, and is therefore recommended (Figure 2.27).

F i g u r e 2.27: Chisel and and osteotome

BONE FILE

Final smoothing of the bone before suturing the

mucoperiosteal flap back into position is usually

performed with a small bone file. The bone file is usually

a double ended-instrument with a small and large end

(Figure 2.28). It cannot be used efficiently for removal

of large amounts of bone, and it is used only for final

smoothing. The teeth of the bone file are arranged in

such a fashion that they remove bone only on a pull

stroke. Pushing the bone file results only in burnishing

and crushing the bone and should be avoided (Figure

2.28).

16

Exodontia Practice

Figure 2.28: Bone file

BUR AND HANDPIECE

A fine method for removing bone is with a bur and

hand-piece. This is the technique that most surgeons

use when removing bone. Relatively high-speed

handpieces with sharp carbide burs remove cortical bone

efficiently. Burs such as fissure bur, round bur are

commonly used. Occasionally, large amounts of bone

need to be removed such as in torus reduction. In these

situations, a large bone bur that resembles an acrylic

bur is used (i.e. carbide trimmer) (Figure 2.29).

F i g u r e 2.29: Different types of burs

The handpiece that is used must be completely

sterilizable in a steam autoclave. When a handpiece is

purchased, the manufacturer's specifications must be

checked carefully to ensure that sterilization is possible.

It should have relatively high speed and torque. This

allows the bone removal to be done rapidly and allows

efficient sectioning of teeth. The handpiece must not

exhaust air into the operative field as dental drills do.

Most high-speed turbine drills used for routine restorative

dentistry cannot be used. The reason is that the air

exhausted into the wound may be forced into deeper

tissue planes and produce tissue emphysema, a

potentially dangerous phenomenon.

INSTRUMENTS TO REMOVE SOFT TISSUE

FROM BONY DEFECTS

The curette, sometimes called the periapical curette, is

an angled, double-ended instrument used to remove soft

tissue from bony defects (Figure 2.30). The principle

use is to remove granulomas or small cysts from

periapical lesions, but it is also used to remove small

amounts of granulation tissue debris from the tooth

socket. The periapical curette is distinctly different from

the periodontal curette in design and function.

F i g u r e 2.30: Bone curette

INSTRUMENTS FOR SUTURING MUCOSA

Once a surgical procedure has been completed, the

mucoperiosteal flap is returned to its original position

and held in place by sutures. The needle holder is the

instrument used to place the sutures.

NEEDLE HOLDER

The needle holder is an instrument with a locking handle

and a short, stout beak. For intraoral placement of

sutures, a 6-inch (15 cm) needle holder is usually

recommended. The beak of the needle holder is shorter

and stronger than the beak of the hemostat. The face

of the beak of the needle holder is crosshatched to permit

a positive grasp of the suture needle and suture (Figure

2.31). The hemostat has parallel grooves on the face

of the beaks, thereby decreasing the control over needle

and suture. Therefore, the hemostat should not be used

for suturing.

Figure 2 . 3 1 : Needle holder

Armamentarium

17

In order to properly control the locking handles and

to direct the relatively long needle holder, the surgeon

must hold the instrument in the proper fashion.

Thumb and ring finger are inserted through the rings.

The index finger is held along the length of the needle

holder to steady and direct it. The second finger aids

in controlling the locking mechanism. The index finger

should not be put through the finger ring, because this

will result in dramatic decrease in control.

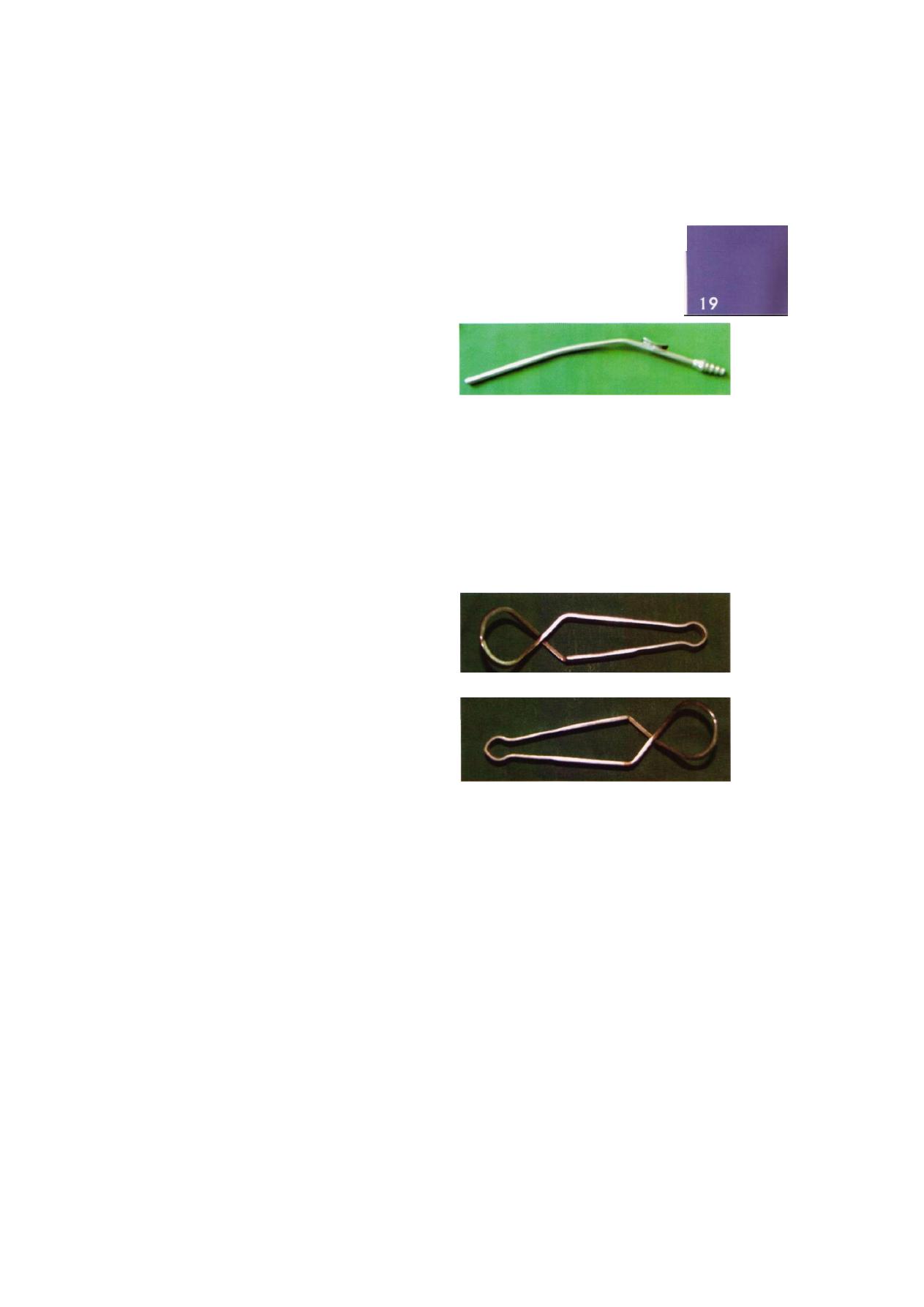

SUTURE CUTTING SCISSOR

Usually sutures are cut at the end of eighth day. Scissor

used for this purpose is specially designed so that it can

reach to the most posterior teeth (Figure 2.32).

F i g u r e 2.32: Suture cutting scissor

NEEDLE

The needle is held approximately two thirds of the

distance between the tip and the end of the needle. This

allows enough of the needle to be exposed to pass

through the tissue, while allowing the needle holder to

grasp the needle in its strong portion to prevent bending

of the needle (Figures 2.33A to C ) . The needle used in

closing mucosal incisions is usually a small half circle

or three-eighth circle suture needle. It is curved to allow

the needle to pass through a limited space where a

straight needle can not reach. Suture needles come in

a large variety of shapes from very small to very large.

The tips of suture needles are either tapered, such as

a sewing needle, or have triangular tips that allow them

to be cutting needles. A cutting needle will pass through

mucoperiosteum more easily than the tapered needle.

The cutting portion of the needle extends about one-

third the length of the needle, and the remaining portion

of the needle is round. The suture can be threaded

through the eye of the needle or can be purchased

already swaged. If the dentist chooses to load his own

1/4 ( ircle 3/81

ircle

1/2 (

J _

ircle , 5/8 c

^|

J ^

Straight

V

El

ra

El

ra

Micropoint spatula £

sj

C. A n a t o m y of a s u r g i c a l needle

F i g u r e s 2.33A to C: Shape, size and anatomy of sutural

needles

18

E x o d o n t i a P r a c t i c e

T a p e r c u t ^ ^ Z ^

B

o

d

y

F i g u r e 2.34A: Different shapes at needle

F i g u r e 2.34B: Tissue disrup- Figure 2.34C: Tissue disrup-

tion is more by double surface t i o n m i n i m i z e d by s i n g l e

stand with eyed needle s u t u r e s t r a n d s w a g e d to

needle

needles for the sake of economy, he must use needles

that have eyes, as has a typical sewing needle. Needles

that have eyes are larger at the tip and may cause slightly

increased tissue injury when compared to the swaged-

on needles (Figures 2.34A to C ) .

SUTURE MATERIAL

Many types of suture materials are available for use.

The materials are classified as resorbable and non-

resorbable, natural and synthetic, monofilament and

polyfilament.

The size of suture is designated by a series of zeros.

The size most commonly used in the suturing of oral

mucosa is 3-0 (000). A larger size suture would be

2-0, or 1-0. Smaller sizes would be 4-0, 5-0, and 6-0

sutures. Sutures of very fine size such as 6-0 are usually

used in conspicuous places on the skin such as the face,

since smaller sutures, usually cause less scarring. Sutures

of size 3-0 are large enough to prevent tearing through

mucosa, are strong enough to withstand the tension

placed on them intraorally, and are strong enough for

easy knot-tying with a needle holder.

Sutures may be resorbable or non-resorbable. Non-

resorbable suture materials include types as silk, nylon

and stainless steel. The most commonly used non-

resorbable suture in the oral cavity is silk. Nylon and

stainless steel are rarely used in the mouth. Resorbable

sutures are primarily made of gut. While the term catgut

is often used to designate this type of suture, gut actually

is derived from the serosal surface of sheep intestines.

Plain catgut resorbs relatively quickly in the oral cavity,

rarely lasting longer than 5 days. Gut that has been

treated by tanning solutions (chromic acid) and is

therefore called chromic gut lasts longer, up to 10 to 12

days. Several synthetic resorbable sutures are also

available. These are materials that are long chains of

polymers braided into suture material. Examples are

polyglycolic acid and polylactic acid. These materials are

slowly resorbed, taking up to 4 weeks before they are

resorbed. Such long-lasting resorbable sutures are rarely

indicated in the oral cavity.

Finally, sutures are classified based on whether or not

they are monofilament or polyfilament. Monofilament

sutures are sutures such as chromic gut. If the dentist

chooses to use the disposable needles, then the suture

will be swaged onto the needle.

Armamentarium

INSTRUMENT TO HOLD THE MOUTH OPEN

When performing extractions or other types of surgery

that requires patients to hold their mouths open widely

for prolonged period of time, dentists commonly use

instruments to assist patients. The bite block is just what

the name implies. It is a rubber block upon which the

patient can rest the teeth. The patient opens his or her

mouth to a comfortably wide position and the rubber

bite block is inserted, which holds the mouth in the

desired position. Should the surgeon need the mouth

to open wider, the patient must open wide and the bite

block must be positioned more to the posterior of the

mouth.

The side action mouth gag can be used by the

operator to open the mouth wider if necessary. This

mouth gag has a ratchet-type action opening the mouth

wider as the handle is closed. This type of mouth gag

should be used with caution as great pressure can be

applied to the teeth and temporomandibular joint and

injury may occur with injudicious use. This type of mouth

gag is useful in patients who are deeply sedated.

F i g u r e 2.35: Suction tip

INSTRUMENT TO HOLD TOWELS AND DRAPES

IN POSITION

When drapes are placed around a patient, they must

be held together with a towel clip. This instrument has

a locking handle and finger and thumb rings. The action

ends of the towel clip are sharp, curved points that

penetrate the towels and drapes (Figure 2.36). When

this instrument is used, the operator must take extreme

caution not to pinch the patient's underlying skin.

INSTRUMENT FOR PROVIDING SUCTION

In order to provide adequate visualization, blood, saliva,

and irrigating solutions must be suctioned from the

operative site. The surgical suction is one that has a

smaller orifice than the type used in general dentistry,

so that the tooth sockets can be suctioned in case a

root tip is fractured and adequate visualization is

necessary. Many of these suctions are designed with

several orifices, so that the soft tissue will not become

aspirated into the suction hole and cause tissue injury

(Figure 2.35).

The suction has a hole in the handle portion that

can be covered as the need dictates. When hard tissue

is being cut under copious irrigation, the hole is covered

so that the solution is removed rapidly. When soft tissue

is being suctioned, the hole is uncovered to prevent tissue

injury.

Figure 2.36: Towel clips

INSTRUMENTS FOR IRRIGATION

When a handpiece and bur are used to remove bone,

it is essential that the area be irrigated with a steady stream

of irrigating solution, usually sterile saline. The irrigation

cools the bur and prevents bone damaging heat

build-up. The irrigation also increases the efficiency of

the bur by washing away bone chips from the flutes of

the bur and by providing a certain amount of lubrication.

Additionally, once a surgical procedure is completed and

before the mucoperiosteal flap is sutured back into

20

Exodontia Practice

position, the surgical field should be irrigated thoroughly

with saline. There are two major systems for accomp-

lishing this. The bulb syringe can be used effectively and

can be refilled easily with one hand. However, the

disadvantage is that it is difficult to sterilize. More

commonly, a large plastic syringe with a blunt 18-gauge

needle is used for irrigation purposes. Although the

syringe is disposable, it can be sterilized multiple times

before it must be discarded. The irrigation needle should

be blunt and smooth so that it does not damage soft

tissue, and it should be angled for more efficient direction

of the irrigating stream.

Anatomical

Considerations

22

Exodontia Practice

Differential diagnosis of the source, or the course, of

pathology in the facial area may, in many instances,

depends on depth understanding of the structure and

relations of the alveolar processes. The extraction of teeth,

surgical exposure of root tips, surgical access to the

maxillary sinus, surgical preparation for oral prosthesis,

etc. must obviously proceed from a familiarity with the

detail and variation found in alveolar structures and their

relations. Planning local anesthesia where the anesthetic

fluid must penetrate the cortical plates to reach the nerves

within the medullary bone clearly depends on knowing

the structural minutiae details of these parts.

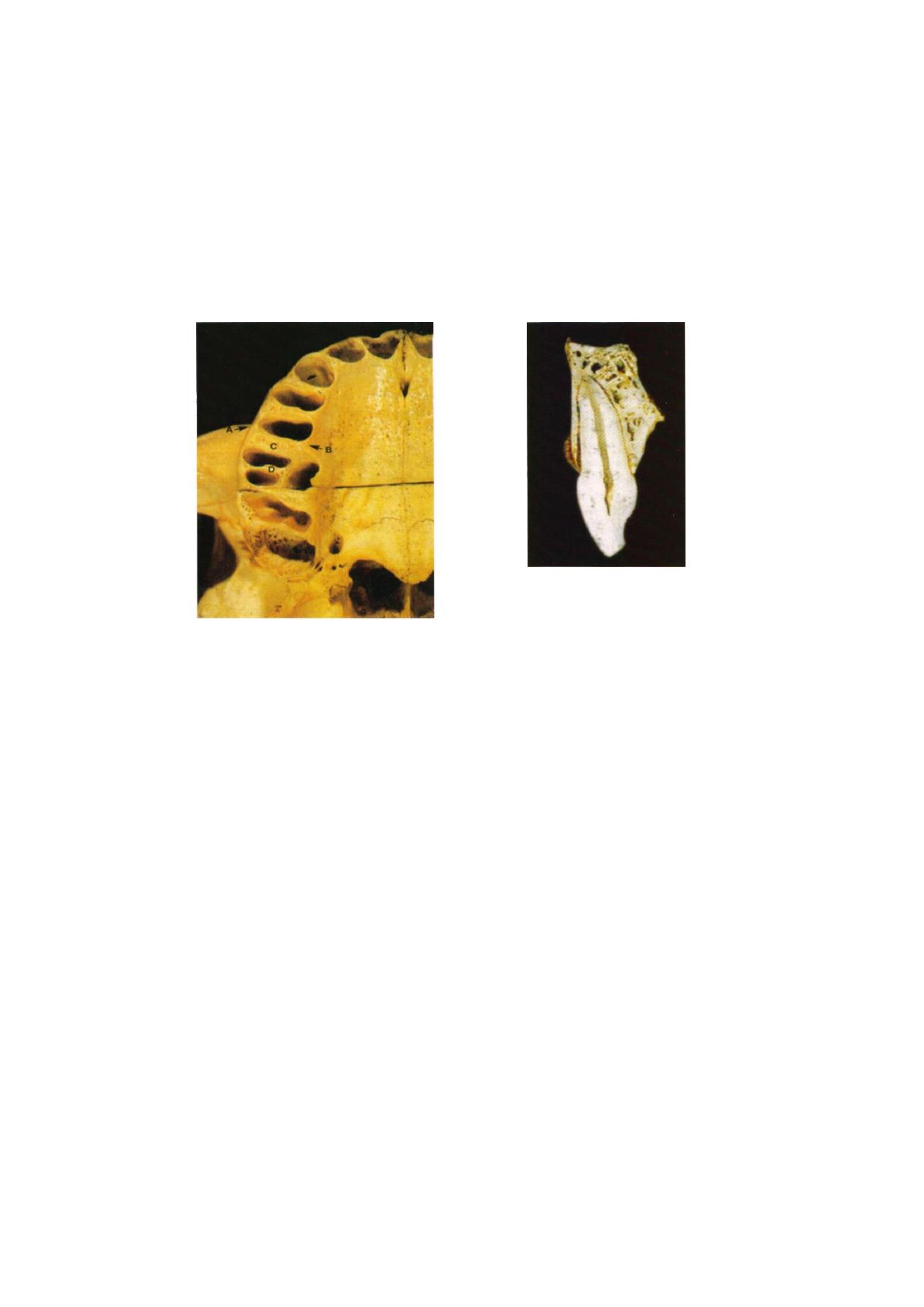

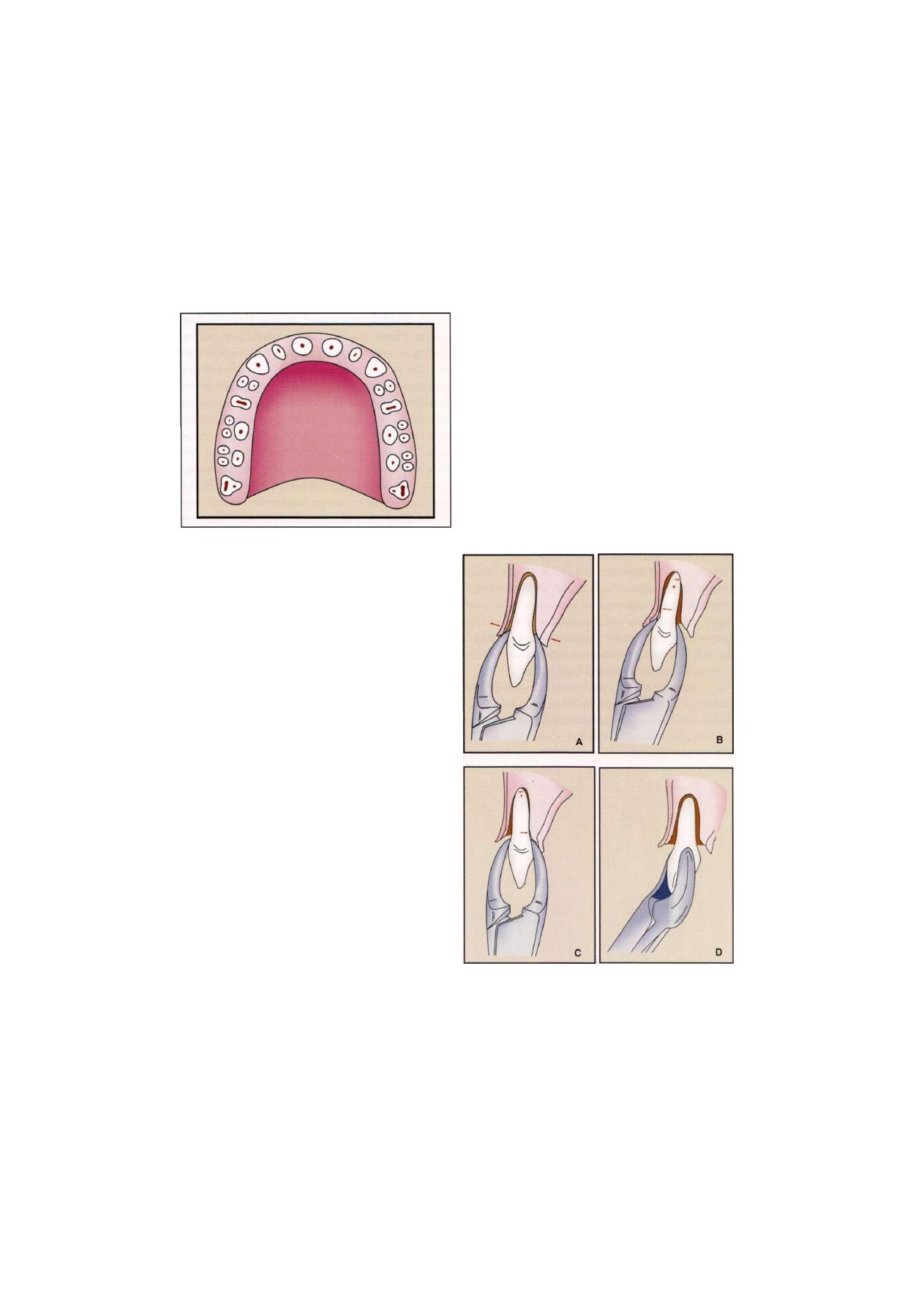

ALVEOLAR PROCESS OF THE MAXILLA

The alveolar process of the maxilla is in relation with

the floor of the nasal cavity and the floor of the maxillary

sinus. Its relation to these cavities is determined by the

functional structure of the maxilla. The canine pillar of

the maxilla, arising from the socket of the canine and

extending upward along the lateral border of the piriform

aperture into the frontal process of the maxilla, is the

most constant bony structure in the base of the alveolar

process (Figure 3.1). The canine pillar is situated lateral

to the entrance into the nasal cavity. Being a functional

reinforcement of the bone, it determines the medial and

anterior expansion of the maxillary sinus, which replaces

nonfunctional bone. It is, therefore, a general rule that

the incisors are below the floor of the nasal cavity, the

premolars and molars are below the floor of the maxillary

sinus, and the canine occupies a neutral position between

the two cavities. This is true even if the nasal cavity is

abnormally wide, because the widening does not

markedly involve the area in front of the incisive canal.

The relations of the apices of the incisors to the nasal

floor are dependent on two factors: height of the face,

especially height of the upper alveolar process, and length

of the incisor roots. Since these two measurements are

not correlated, it is necessary to examine each case

individually and to ascertain the relations between the

incisor sockets and the nasal floor by radiographic

examination. It is a general rule that the root of the lateral

incisor does not show as close a relation to the nasal

floor as does the root of the central incisor, because the

root of the lateral incisor tends to curve toward the outer

rim of the nasal aperture. In addition, it has to be

remembered that the floor of the nasal cavity ascends

slightly laterally, which also increases the distance

between the fundus of the socket of the lateral incisor

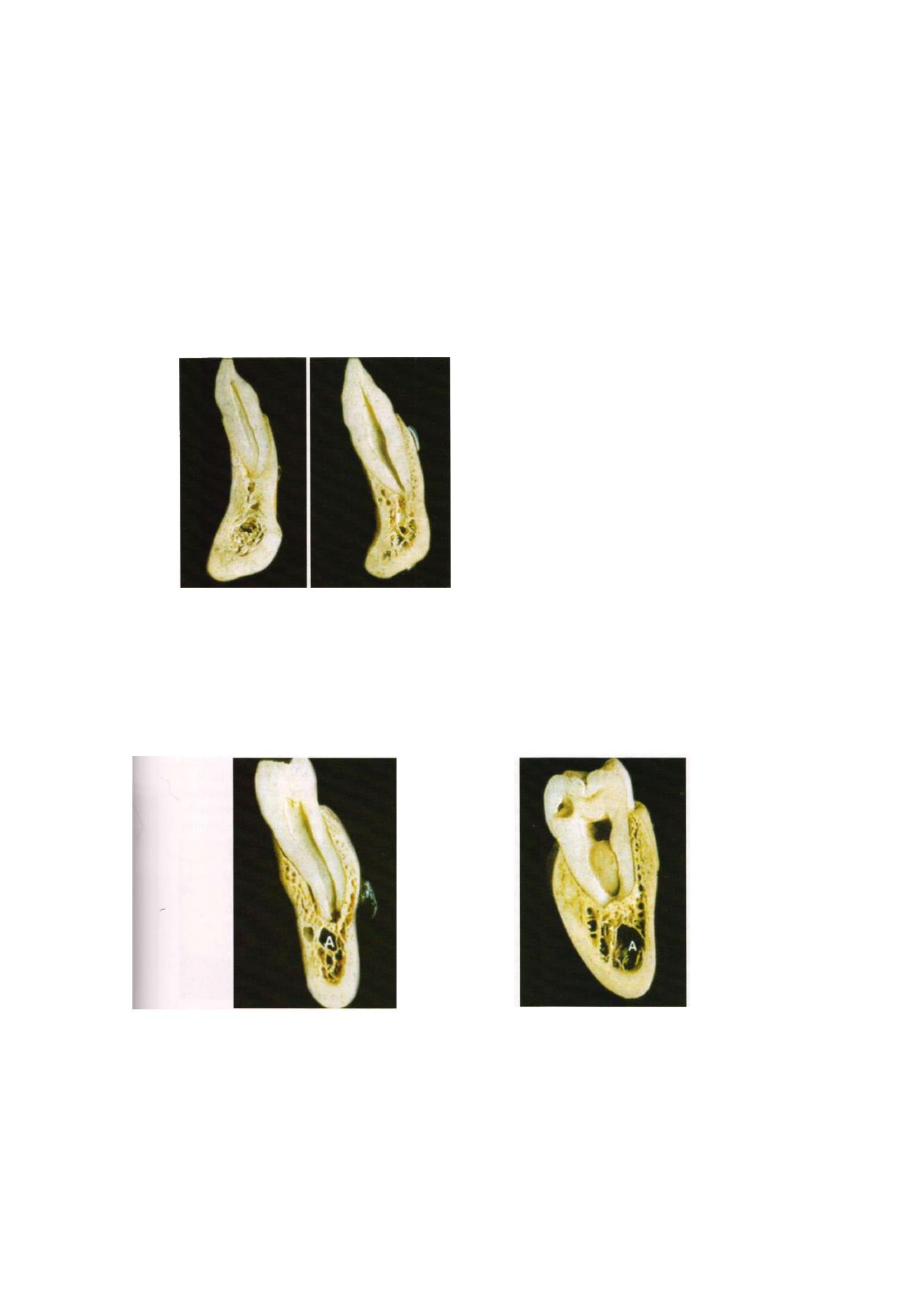

and the nasal floor (Figures 3.2A and B ) .

In persons with a relatively short alveolar process and

long roots, the central incisor may actually reach the thin

F i g u r e 3 . 1 : Relation of maxillary teeth with

nasal floor and maxillary sinus

F i g u r e 3.2A: Maxillary teeth

Anatomical Considerations

23

F i g u r e 3.2B: Thickness of alveolar process

of maxillary teeth

compact bony plate that forms the floor of the nasal

cavity. The apex of the tooth is then separated from the

nasal cavity by only a thin plate of bone. In the other

extreme a rather thick layer of spongy bone may be

interpose between the nasal floor and the socket of the

central incisor.

The apex of the lateral incisor shows, in principle,

the same variations in its relation to the nasal floor, but

it rarely actually comes into contact with the nasal floor

(Figure 3.3) The configuration of the alveolar process

in the incisal region is, dependent on the formation of

the palate. The inner plate of the alveolar process ascends

at a moderate angle if the palate is low and then curves

without a break into the horizontal roof of the oral cavity.

If the palate is high, the inner plate of the alveolar process

is steep in its anterior part, and there is a fairly sharp

angle between the alveolar process and the roof of the

mouth. These variations decisively influence the amount

and the configuration of the spongy bone, the

retroalveolar spongiosa, between the outer and inner

Figure 3.3: Lateral incisor in alveolar bone

plates of the alveolar process and the nasal floor. In a

flat or low palate this space is roughly triangular and

rather wide. In a high palate the retroalveolar spongiosa

is restricted and occupies, a more rectangular area.

It has to be remembered that the difference between

a low and a high palate is expressed not only in

quantitative measurements but also in the changed

configuration of the palate. In the incisor region the

differences in shape and in the molar region the differen-

ces in relative size are more prominent, whereas the

premolar area is a zone of transition. In the anterior

region of the maxilla the inclination of the inner alveolar

plate, or palatine plate, is slight in the low palate and

steep in the high palate. In the molar region of the maxilla

the angle between the oral roof and the inner surface

of the alveolar process is always nearly a right angle,

so that the high palate is characterized mainly by an

increase in the length of the alveolar process.

The sockets of the incisors are eccentrically placed

in the alveolar process, the axis of the root and socket

being more nearly vertical than the axis of the alveolar

process. Thus, the alveolar bone proper on the labial

surface of the root fuses with the external plate of the

alveolar bone, whereas palatally a wedge-shaped area

2

Exodontia Practice

of spongy bone is found between the alveolar bone

proper and the palatine or inner plate of the alveolar

process. This is why abscesses originating in the incisor

teeth in most instances perforate the labial plate of the

alveolar process and open into the vestibule of the oral

cavity. There is, however, one important exception to

this rule. In a rather high percentage of incisors the apical

part of the root of the lateral incisor is sharply curved

lingually, and its apical foramen is placed in or near the

center of the retroalveolar spongiosa and rather distant

from the outer alveolar plate.

The relations of the incisors to the nasal floor explain

the fact that an abscess arising from the central incisor

may open into the nasal cavity or that a radicular cyst

of an incisor may bulge into the inferior nasal meatus,

even causing an occlusion of the nostril.

The canine is embedded in the lower part of the

canine pillar of the maxilla . If this pillar contains a great

amount of spongy bone, it is continuous with the retro-

alveolar spongiosa in the incisal region (Figure 3.4).

Because of the position of the canine tooth in the canine

pillar, neither nasal cavity nor maxillary sinus has intimate

relations to the socket and the root of the canine. In

extreme cases, however, the maxillary sinus may extend

Figure 3.4: Canine position in the maxillary alveolus

forward so that it approaches the distolingual circum-

ference of the socket of the canine in a rather broad

front. The same is sometimes true for the nasal cavity,

which approaches the mesiolingual surface of the canine.

The relation of the canine to the plates of the alveolar

process is, in principle, the same as that of the incisors,

its root being eccentrically embedded in the alveolar

process. The compactness and the size of the canine

root cause an even greater bulging of the socket toward

the labial surface of the alveolar process, and the alveolar

eminence of the canine tooth is the most prominent

in the upper jaw.

The premolars and molars are, as a rule, situated

below the floor of the maxillary sinus. Whether the

relations between the tooth and the sinus are intimate

or not depends on the development of the inferior

alveolar recess of the maxillary sinus. But even in cases

in which the base of the alveolar process is deeply

excavated by the maxillary sinus, the first premolar is

almost always farther removed from the floor of the

sinus than are the second premolar and the molars,

because in the premolar area the floor of the sinus arises

before continuing into the anterior wall. This, in turn,

is correlated to the widening of the canine pillar at its

base. Thus, with exception of extreme expansion of the

maxillary sinus, the alveolar fundus of the first premolar

is separated from the sinus floor by a layer of spongy

bone.

The transition of the inner plate of the alveolar process

into the horizontal part of the hard palate occurs in the

region of the first premolar in a more pronounced angle,

and differences between a low and a high palate are

here of a more quantitative character than they are in

the anterior region of the maxilla. The relation of the

first premolar socket to the alveolar process as a whole

and to the retroalveolar spongiosa varies according to

the formation of the root. If the first premolar has a single

root, the socket is in close relation to the outer alveolar

plate and is separated from the inner plate by spongy

bone. As in the incisor-canine area, the outer alveolar

plate is, in reality, a fusion between the alveolar bone

Anatomical Considerations

25

proper and the alveolar plate and often is extremely thin.

In many persons the outer plate may even be defective,

or fenestrated, especially in the apical third of the alveolar

eminence. If the first premolar possesses two roots, the

buccal one is closely applied to the outer alveolar plate,

whereas the socket of the lingual root is placed almost

in the center of the retroalveolar spongiosa.

The relation of the second premolar to the maxillary

sinus is closer than that of the first premolar. Only if the

alveolar recess of the maxillary sinus is absent or poorly

developed does a layer of spongy bone intervenes

between the socket of the second premolar and the floor

of the sinus. In the majority of persons the floor of the

sinus dips down into the immediate neighborhood of

the second premolar. Its socket is then separated from

the sinus only by a thin layer of compact bone. The sinus

may even extend below the level of the alveolar fundus

of the second premolar, and the socket causes a slight

prominence at the floor of the sinus. If the expansion

of the sinus goes further, the thin bony plate between

the sinus and the socket of the second premolar may

F i g u r e 3.5: Premolar in maxillary alveolar bone

showing relation with maxillary sinus

even disappear, so that only soft tissues separate the apex

of the root from the cavity of the sinus; in other words,

the periodontal tissue is then in direct contact with the

mucoperiosteal lining of the sinus. In the region of the

second premolar the inner alveolar plate is more nearly

vertical, except in cases of extremely low palate. The

retroalveolar spongiosa is reduced, and it almost

disappears in the region of the molars (Figure 3.5).

Intimate relations between the tooth and the maxillary

sinus are the rule in the region of the molars. The inter-

vention of a substantial layer of bone between the

alveolar fundus and the maxillary sinus is here an

exception. The sockets of the molars almost always reach

the floor of the sinus, and frequently the apices of some

or all of the molar roots protrude into the sinus, where

small rounded prominences at the floor of the sinus

mark the position of the root apices. Bony defects at

the height of these prominences are not at all rare and

sometimes are of fairly large extent. The divergence of

the molar roots, especially in the first molar, frequently

permits an extension of the sinus downward toward the

furcation of the roots. Often sickle-shaped buttresses of

bone traverse the floor of the sinus in a frontal plane

between the molars whose roots protrude into the sinus.

Sometimes these ridges connect the prominence of one

of the buccal roots with that of the lingual root. Branches

of the alveolar nerves, destined for the palatal roots of

the molars, use these sickle-shaped folds as bridges; they

run in narrow canals that often are open toward the

sinus for a variable length. The bony crests divide the

alveolar process into several chambers, a peculiarity that

should be kept in mind in the search for a root fragment

that has been displaced into the sinus.

Differences in the relation between the first and the

second molars to the sinus are caused mainly by the

greater divergence of the palatal and the buccal roots

in the first molar. The palatal root of the first molar

frequently extends toward the base of the bony partition

between the nasal cavity and the maxillary sinus and

may, in extreme cases, even extend toward the lateral

area of the nasal floor.

26

Exodontia Practice

Behind the socket of the upper third molar the

posterior end of the alveolar process forms a variably

large knob-shaped bony prominence, the alveolar

tubercle. The junction of the maxilla and the pterygoid

process of the sphenoid bone, mediated usually by the

palatine bone, occurs at a variable level-above the free

margin of the alveolar process behind the last molar.

If this junction is high and if the alveolar tubercle is

hollowed out by the maxillary sinus, the bone behind

the maxillary third molar is weak. If the extraction of

a third molar is attempted by applying an instrument

that exerts pressure distally, the entire corner of the

maxilla may be broken off and the wisdom tooth is not

removed from its socket, but the tooth and socket are

separated from the maxilla. As a consequence of this

fracture, the oral cavity and the maxillary sinus

communicate through a wide opening. The possibility

of this alveolar fracture should caution against attempts

to extract or to loosen the upper third molar by

introducing an elevator between the second and third

molars and exerting pressure distally.

The vertical position of the inner plate of the alveolar

process in the molar region restricts the retroalveolar

spongiosa to small areas lingual to the mesiobuccal root

because the lingual root is situated alongside the

F i g u r e 3.6: Position of the molar in

maxillary cellular process

distobuccal root. The socket of the lingual root fuses

with the inner plate of the alveolar process or is at least

close to it. Mesial to the lingual root, however, a block

of spongy bone intervenes between the socket of the

mesiobuccal root and the lingual plate of the alveolar

process. This arrangement of the spongy bone is the rule

in the region of the first and the second molars; it is,

however, often obscured around the third molar because

of the great variability of third molar roots (Figure 3.6).

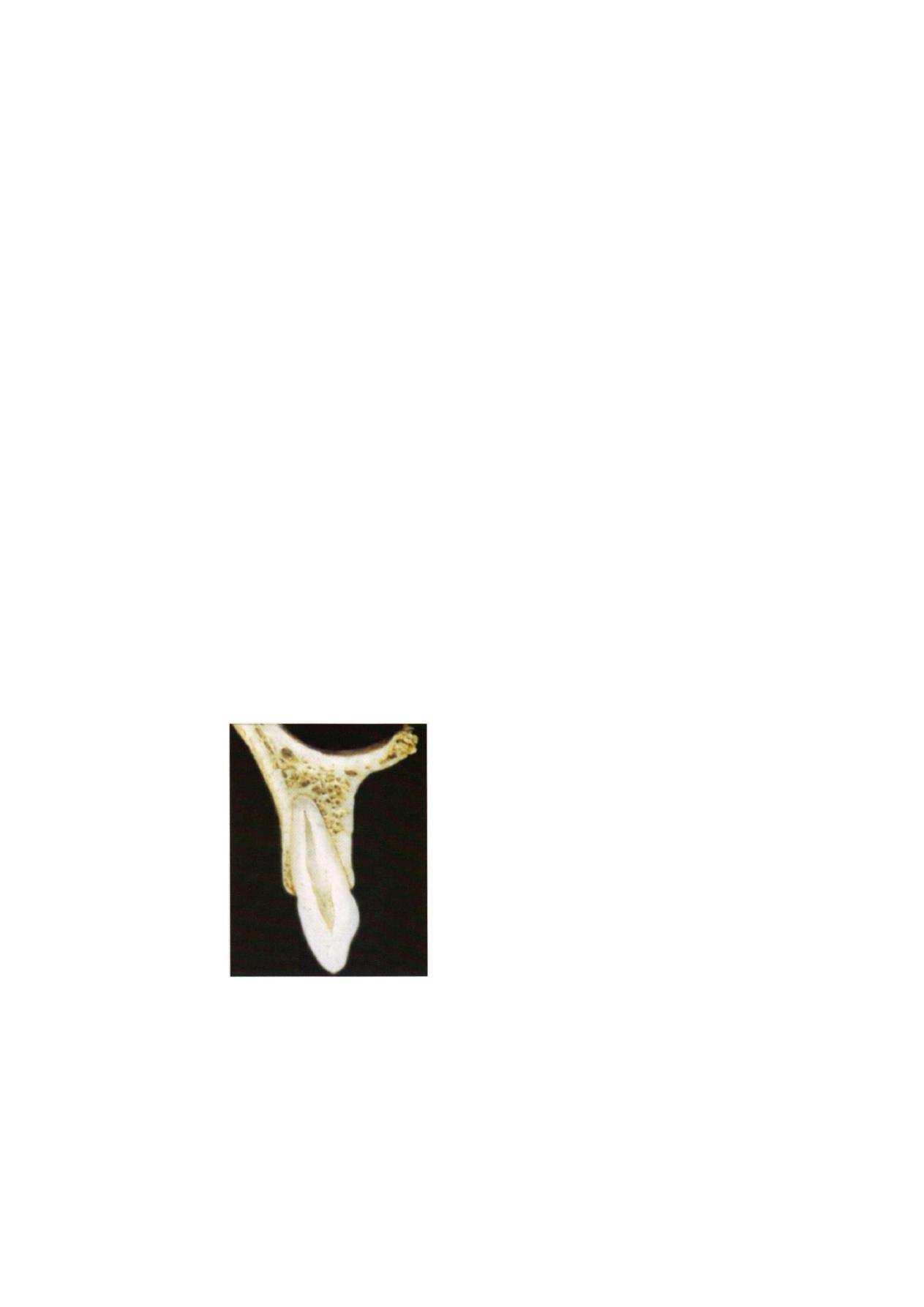

ALVEOLAR PROCESS OF THE MANDIBLE

Conforming to the great strength and more uniform

solidity of the mandible, the lower alveolar process is

in most areas far stronger than that of the upper jaw.

Only in the incisor and canine areas are the outer and

inner plates of the alveolar process thin; distally,

however, they increases rapidly in thickness (Figure 3.7).

F i g u r e 3.7: Alveolar process of the mandible

It is of clinical importance that the relation of the

alveolar bone proper to the compact plates and the

spongiosa of the alveolar process varies widely. In the

anterior part of the mandible, in the region of the incisors

and the canine, the alveolar process is narrow in the

labiolingual direction, and in most jaws the alveolar bone

proper fuses for the entire length of the root, or at least

for most of its length, with the outer and the inner alveolar

plates (Figures 3.8A and B). Only rarely is there a restricted

zone of spongiosa lingual to the apical part of the socket.

Anatomical Considerations

2

of the alveolar process. The alveolar bone proper is then

fused for a variable length with one of the alveolar plates.

The premolars and the first molar are mostly in close

relation to the outer alveolar plate. The second and third

molars, however, often show a reversed relation, which

is almost a rule for the third molar. This is not so much

the consequence of a different inclination of the last

mandibular teeth but of a medial shift of the alveolar

process itself in relation to the bulk of the mandibular

body. The oblique line on the outer surface of the

mandible in the region of the second and third molars,

and a fairly thick layer of spongy bone is interposed

between the socket and the outer compact layer of the

bone, but this bone cannot be regarded as part of the

alveolar process in a strict sense. The described relations

are of clinical importance because an inflammation

originating in the second and especially in the third molar

will often perforate the inner plate of the mandible. The

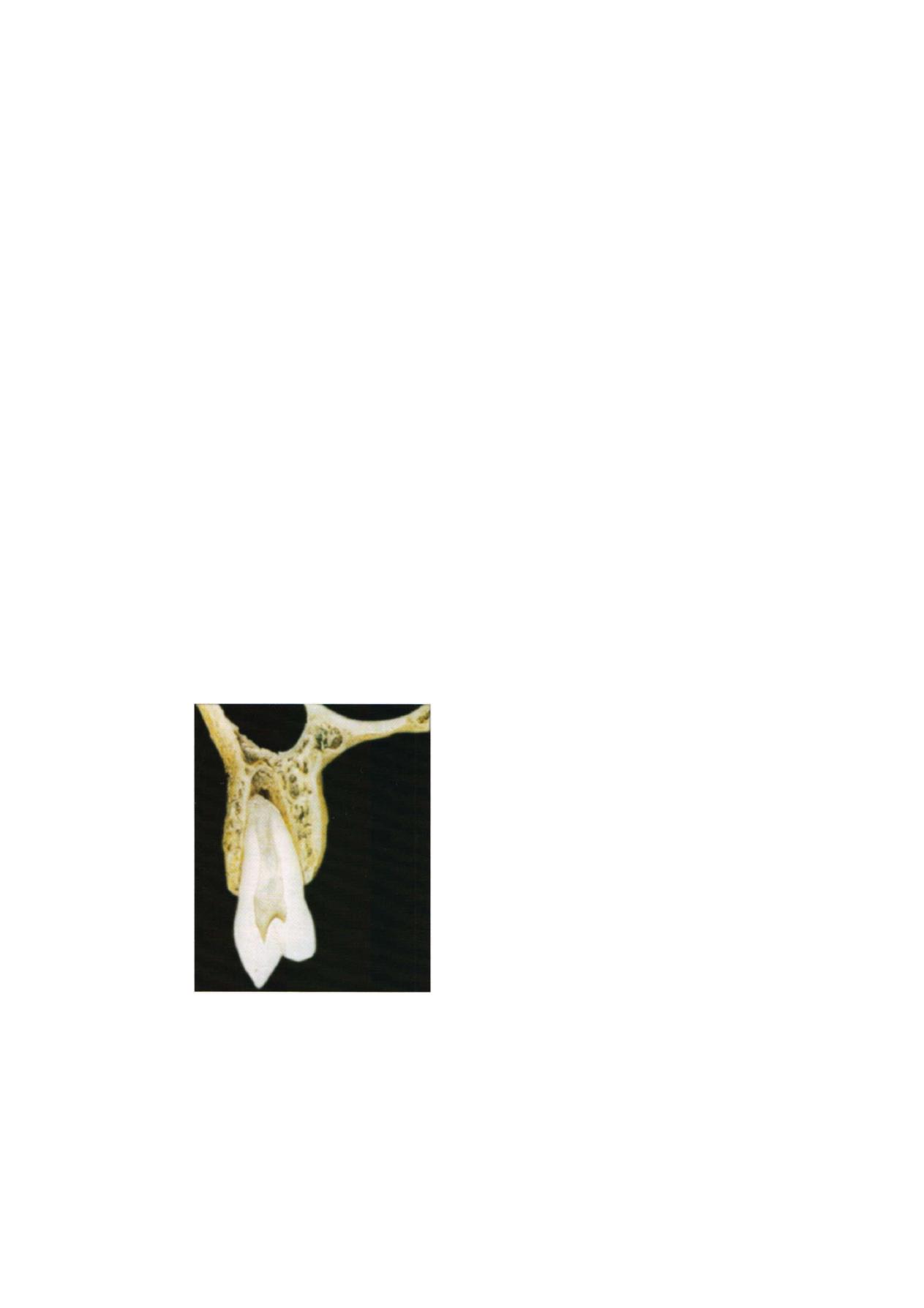

variable relations of the socket and root can best be

evaluated in buccolingual sections through the mandible

at the level of the third molar. In such sections the socket

of the wisdom tooth projects on the inner, or medial,

surface of the mandible somewhat like a balconu. and

F i g u r e s 3.8A a n d B: (A) Incisor and canine in

mandibular alveolar process

The position of the sockets of the premolars and

molars in the spongy bone of the mandible varies (Figure

3.9). Only infrequently is the socket symmetrically placed

between the outer and inner plates. In most cases the

position of the socket is asymmetrical; that is, the axis

of the root and the socket is inclined against the axis

F i g u r e 3.9: Position of premolar in the F i g u r e 3.10: Position of molar in the

mandibular alveolar process mandibular alveolar process

28

Exodontia Practice

in some persons it is shifted entirely inside the arch of

the mandibular body. The further the socket projects

inward, the thinner is its lingual wall and the closer is

the apex of the root to the inner surface of the bone

(Figure 3.10).

At or above the level of the fundus of the socket the

mylohyoid line can be seen on the medial surface of

the jaw. The variations in the relation of this line to the

third molar are of great importance because the

mylohyoid muscle, which forms the floor of the oral

cavity, is attached to this line. The relations of the

mylohyoid line to the apex of the third molar depend

on three factors: the height of the mandibular body, the

anteroposterior length of the mandibular alveolar

process, and the length of the roots of the third molar.

The level of the apex of the third molar roots is found,

as a rule, below the level of the mylohyoid ridge,

especially if the roots of the wisdom tooth are long, if

the alveolar process is relatively short, and if the

mandibular body is of below-average height. It is clear

that in such cases a perforating abscess of the wisdom

tooth will not appear in the oral cavity but below its floor

in the connective tissue of the submandibular region.

Lateral, or buccal, to the alveolus of the lower third molar,

the massive bone forms either a variably wide horizontal

edge or a variably wide and variably deep groove. The

outer edge of this bony field is the oblique line where

it turns anteriorly and inferiorly in continuation of the

anterior border of the mandibular ramus. According to

the relative length of the alveolar process, the wisdom

tooth is either entirely in front of the ascending ramus

or its distal part is flanked by the most anterior part of

the ramus. In the latter case the accessibility of the lower

wisdom tooth is restricted; especially if the superficial

tendon of the temporal muscle is well developed and

accentuates the anteriorly projecting border of the ramus.

Of special importance are the relations of the lower

teeth to the mandibular canal and to its contents, the

inferior alveolar nerve and the accompanying blood

vessels. The second premolar and the molars may be

rather close relation to the mandibular canal itself,

whereas the first premolar shows relation to the mental

canal. Canines and incisors are placed in the region of

the narrow incisive canal, the anterior continuation of

the mandibular canal.

In the relation of the root apices to the mandibular

canal three types can be established. The most frequent

type is that in which the canal is in contact with the

alveolar fundus of the third molar, and the distance

between the canal and the roots increases anteriorly.

When the canal is in proximity to the third molar root,

the thin lamella of bone that bounds the mandibular canal

may even show a fairly large defect, and the periapical

connective tissue of the third molar is in direct contact

with the contents of the mandibular canal. Severe pain

of a neuralgic character after the extraction of a lower

wisdom tooth or during inflammations of its periodontal

ligament is easily explained by these relations.

The other two types of topography of the mandibular

canal occur only in a small number of persons. In cases

of a relatively high mandibular body combined with

roots of moderate length, the mandibular canal has no

intimate relations to any one of the posterior teeth. The

reverse is true in those who have a low mandible and

relatively long roots. In these cases the mandibular canal

may be in close contact with the roots of all the three

molars and the second premolar (Figure 3.11).

The last-described type is normal for children and

most young persons in whom the definite height of the

mandible has not yet been attained. During further

F i g u r e 3 . 1 1 : Relation of tooth apices with inferior

alveolar nerve and mandibular canal

Anatomical Considerations

29

growth, the mandibular body increases in height by

apposition at the free border of the alveolar process,

and the teeth, by their correlated vertical eruption, move

away from the mandibular canal.

The frequent impaction of the lower third molar may

bring about a still closer and more complicated relation

of its root to the mandibular canal and its contents. In

impaction of the wisdom tooth the developing roots

grow into the bone. If the tooth is in an oblique or nearly

vertical position, and if the growing roots are not stunted

or bent, they frequently extend beyond the level of the

mandibular canal. However, an actual meeting between

roots and canal is rare, although a routine radiograph

may give this illusion. Since the impacted lower third

molar is usually lingually inclined, its roots pass the

mandibular canal on its buccal side. Only in a minority

of cases are the roots located lingual to the canal if the

wisdom tooth is abnormally inclined and especially if

there is a considerable lingual shift of the posterior end

of the alveolar process.

In rare instances the roots of an impacted third molar

grow straight toward the mandibular canal and then, con-

tinuing to grow, envelop its contents. The wisdom tooth

then has a root that is, to a variable extent, divided into

a buccal and a lingual part. The mandibular canal may

lie in this abnormal bifurcation, or, if the apices of the

roots fuse below the canal, the alveolar nerve and blood

vessels may pass through a canal in the roots of the

wisdom tooth. The complications caused by this

fortunately rare situation during extraction of such a

wisdom tooth are self-evident. It is as though the loosened

wisdom tooth were held in its socket by an elastic band.

Cutting of this "band" means cutting the alveolar nerve

and blood vessels. In view of these complications, the

routine radiographs should be supplemented by one

taken in vertical projection with the film in the occlusal

plane. If by such a picture the diagnosis of the described

situation can be made, division of the wisdom tooth

into a buccal and a lingual part should be attempted

to liberate the contents of the mandibular canal.

The relations of the first premolar to the mental canal

and foramen deserve special attention. Ordinarily the

mental canal arises from the mandibular canal in the plane

of the first premolar; sometimes its origin is slightly distal

to this plane. From its origin inside the mandible, the

short mental canal runs outward, upward, and backward

to open at the mental foramen, situated between the

two premolars or in the plane of the second premolar.

The oblique course of the mental canal makes it

understandable that its outer end is at a higher and more

posterior level than its inner end. This explains the fact

that in radiographs the mental foramen often is projected

on the apex of the second premolar but rarely on the

apex of the first premolar. Since at this point the

mandibular canal is seldom in the immediate contact to

the apices of these teeth, the mental foramen appears

to have no connection with the mandibular canal and

often is diagnosed wrongly as a pathologic defect of the

bone, for instance as a periapical granuloma.

It was mentioned that in the premolar and molar

region the outer and inner plates of the lower alveolar

process consist of a fairly thick layer of compact bone.

Attempts to anesthetize the inferior dental nerves by

subperiosteal or supraperiosteal injections in this region

are failure. In the region of the canine and incisors this

method of injection is successful if the anesthetic is

injected into the mental fossa above the mental

tuberosity. Two facts make it advisable to inject fairly

close to the lower border of the mandible and rather

far below the level of the apices of the anterior teeth.

The first fact is that the incisal canal is situated at a lower

level than the mandibular canal itself; the second is that

the outer compact of the mandible in the mental fossa

is always perforated by a few small openings that allow

an entrance of the injected fluid into the spongy core

of the bone and thus to the incisive nerve.

Chapter

Indications

and

Contraindications

32

Exodontia Practice

INDICATIONS

Following are the indications of exodontia.

PERIODONTAL DISTURBANCES

They form the common cause for dental extraction in

India. When the teeth are periodontally involved, the

clinician must decide whether to extract the tooth or not.

The final decision depends on (a) the success of

periodontal therapy, (b) patient's attitude towards the

concept of conserving such teeth and (c) economic and

time factors. Even if the patient desires to save the tooth,

loss of more than 40% of periodontal support warrants

extraction.

DENTAL CARIES

When the tooth is extensively damaged by dental caries,

the dental surgeon must evaluate the feasibility of

conserving the carious tooth. Even if the patient and the

dental surgeon desire to save the tooth, it is indicated

for extraction if all the conservative procedures have

failed. This may be either because of technical reasons

or if the patient fails to cooperate. Sometimes, the sharp

margins of the teeth repeatedly ulcerate the mucosa.

Multiple carious teeth may lead to deteriorating oral

hygiene. In such cases, removal of teeth will improve

the oral hygiene.

PULP PATHOLOGY

If endodontic therapy is not possible or if the tooth is

having pulpal pathology, extraction is indicated.

APICAL PATHOLOGY

If the teeth fail to respond to all conservative measures

to resolve apical pathology, either because of technical

reasons or because of the systemic factors, such teeth

are indicated for extraction before the apical pathology

widens with the consequent involvement of the adjoining

teeth.

ORTHODONTIC REASONS

During the course of orthodontic treatment, a few teeth

may require extraction. They fall into any one of the

following reasons:

Therapeutic Extractions

To gain pace during the realignment of malposed teeth,

extraction of teeth like premolars or molars are indicated.

Malposed Teeth

The teeth in the dental arch are malpositioned.

Orthodontist may find it difficult to realign them. In

such circumstances, those teeth are indicated for

extraction.

Serial Extraction

During mixed dentition period, dental surgeon may have

to extract a few deciduous teeth in a chronological order

to prevent malocclusion as the child grows. As part of

preventive dentistry, judicious extraction of deciduous

teeth provides enough space eruption of permanent

successors in a sequential way. This is known as serial

extraction. However before advising extraction, these

teeth require proper evaluation and expert orthodontic

opinion. Otherwise, instead of achieving stability of the

dental arch, injudicious extraction can lead undesirable

esthetics like spacing between teeth may even produce

unacceptable facial profile Therefore, decision for

extraction of teeth for orthodontic reasons should be

based on:

a. Orthodontic assessment

b. Evaluation of the soft tissues like lips, tongue, etc.

PROSTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS

Extraction of teeth is indicated for providing efficient

dental prosthesis. For example, to provide better design

and success of partial dentures, a few selected teeth may

have to be extracted. At the same time, caution is required

if a patient requests the dental surgeon to extract a few

Indications and Contraindications

remaining teeth to enable him to have complete dentures.

It is a known fact that atrophies of the bone results in

decreased denture bearing area and the consequent

decreased denture stability. But the retention of a few

teeth like canines control the atrophy of the jaws.

Likewise, intentional retention of a few teeth may be

helpful to utilize them as abutments. Hence, careful

evaluation by the prosthodontist is necessary for

extracting teeth for prosthetic considerations.

IMPACTIONS

Retention of unerupted teeth beyond the chronological

eruption may sometimes be responsible for facial pain,

periodontal disturbances of the adjoining teeth temporo-

mandibular joint problems, bony pathology like cysts and

pathological fracture of the jaws. Impact ions may

predispose to anterior overcrowding of teeth. Careful

evaluation of such patients including general condition

and professional competence of the dental surgeon are

some of the important considerations for removal of such

impacted teeth.

SUPERNUMERARY TEETH

These teeth may be malpositioned or unerupted. Such

teeth predispose to malocclusion, periodontal distur-

bances, facial pain, bony pathology or may even

predispose to esthetic problems. Unless retention of such

supernumerary teeth are advantageous to the patients,

they are indicated for extraction.

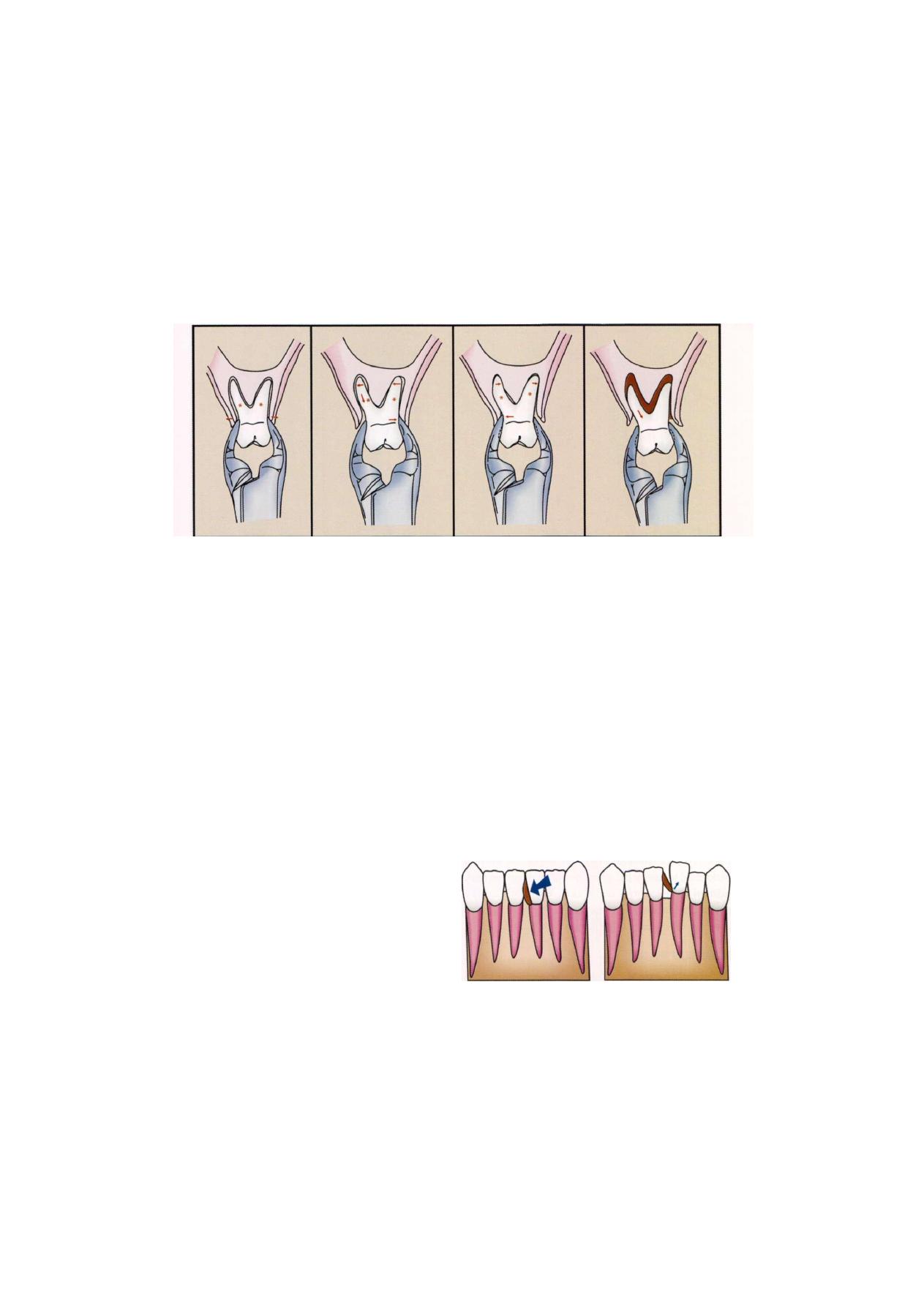

TOOTH IN THE LINE OF FRACTURE

This has been controversial over the course of years.

The present concept is to extract the tooth in the line

of fracture if (a) it is a source of infection at the site

fracture, (b) the tooth itself is fractured, (c) the retention

may interfere with fracture reduction or with healing of

the fracture. Formerly, all the teeth in the line of fracture

were routinely removed. But now, a conservative

approach is advocated and hence extraction of such

teeth requires guarded approach.

TEETH IN RELATION TO BONY PATHOLOGY

They are indicated for extraction. For example, they are

involved in cyst formation, neoplasm or osteomyelitis,

extraction is indicated. However, carefully evaluation is

required before extracting teeth involved in the cyst

formations. If any chance exists for guiding the tooth

to erupt to normal occlusion, efforts must be directed

to conserve such teeth. Hence, proper decision must be

taken based on the individual case.

ROOT FRAGMENTS

They may remain dormant for a long period. Hence,

every patient must be carefully evaluated to decide

whether removal of root fragments is necessary.

For example, roots may be at the submucosal level

producing recurrent ulceration under the denture. Such

ulceration may be painful or may undergo neoplastic

changes. Such roots warrant removal. Sometimes, root

fragment may be involved in the initiation of bony

pathology like osteomyelitis, cyst or neoplasm. If such

fragments are in close association with neurovascular

bundle, the patient may complain of facial pain or

numbness. Statistically, it has been observed that many

broken root fragments remain symptomatic. This has

resulted in the controversy as to whether they are

indicated for removal. As a general rule, very small

fragments may be left alone and the patient is to be kept

under periodical observation. All the other root fragments

are indicated for removal. As the age advances, the

patients become medically compromised. Hence,

removal is indicated as soon as it is diagnosed, instead

of waiting for the symptoms to appear before general

health of the patient presents any problems.

TEETH PRIOR TO IRRADIATION

Irradiation is one of the modalities of treating oral

carcinomas. Previously as a prophylactic measure, all

the teeth in the region of irradiation used to be extracted.

But now, all the precautions are taken to conserve the

teeth prior to irradiation. Hence, all the patients before

Exodontia Practice

irradiation must be carefully examined so that a decision

is taken regarding the extraction of such teeth. If the

oral hygiene can be maintained satisfactorily, routine

prophylactic extraction of these teeth are not to be

encouraged. Only teeth which cannot be maintained in

a sound condition require removal.

FOCAL SEPSIS

Sometimes, teeth may appear apparently sound. But

radiological evaluation is a guiding factor to decide

whether any teeth are to be considered as foci of

infection. In such circumstances, weightage is in favor

of the underlying systemic disorders like dermatological

lesions, facial pain, uncontrollable ophthalmic problems

etc. In such conditions, doubtful teeth are extracted

instead of resorting to any conservative methods of

management.

ESTHETICS

Due to certain compelling reasons like marriage and

job opportunities, some teeth may require attention

for esthetic considerations. But due to time factor, it

may not be possible to improve esthetics by any

conservative orthodontic or surgical means. If so,

such teeth are indicated for extraction, provided it is

followed by immediate prosthetic restoration in a shorter

duration.

ECONOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Sometimes, the dental surgeon and the patient are faced

with economic constraints even though technically

conservation of teeth may be feasible. In such cases,

extraction may be the only other alternative method of

choice. However, the benefit of doubt is left to the

discretion to the patient in such circumstances and

extraction of teeth is indicated as a last resort.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Even if the tooth is indicated for removal, the presence

of certain factors makes the tooth contraindicated for

extraction. They may be relative or absolute contraindi-

cations. They can be considered relative, if the