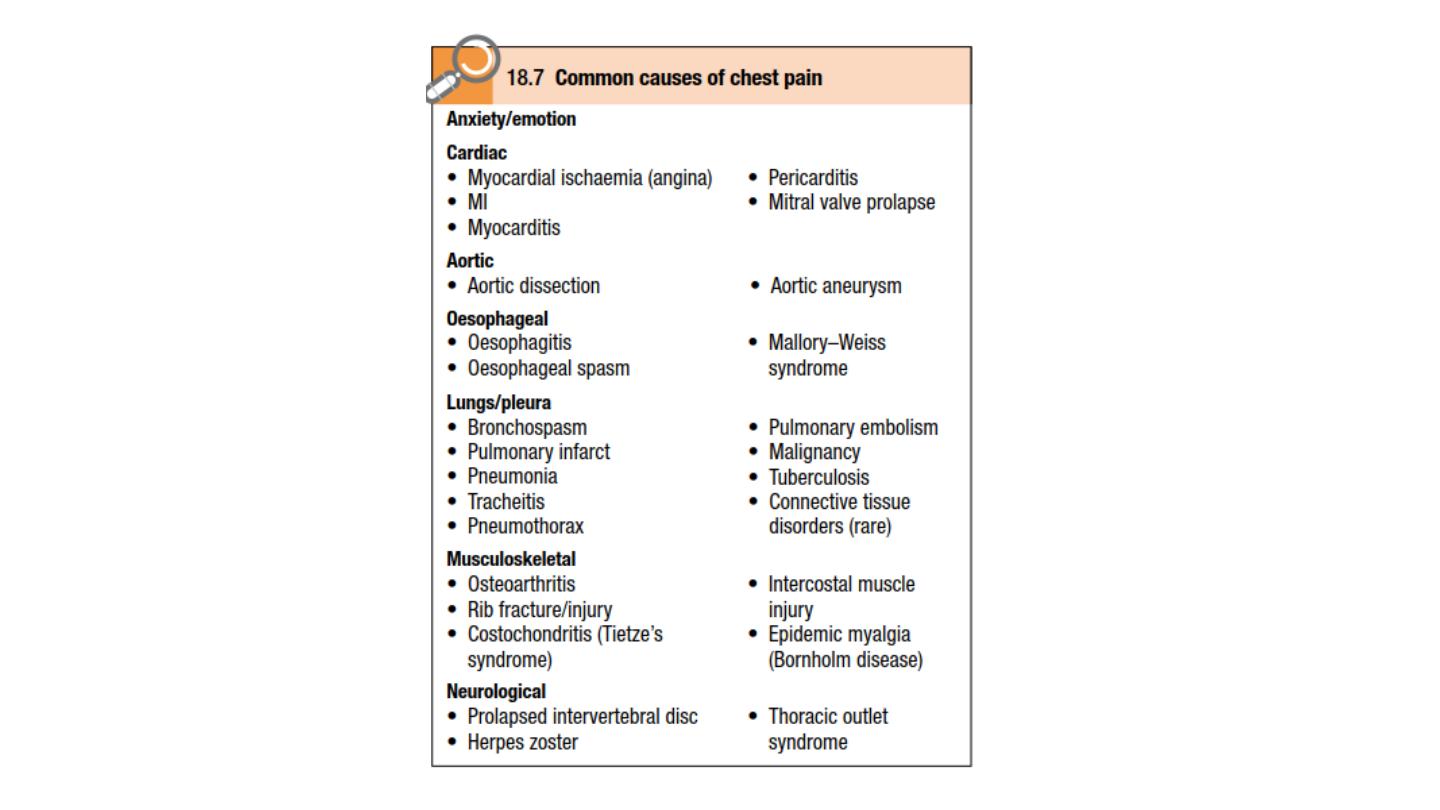

Cardiac Chest pain

: اعداد وتقديم الطلبة

زينة بشار ذنون

مروة عبد الكريم

عمر عبد المحسن

Supervised by

: Dr. jasim Mohamad Taib

stable angina

Is transient myocardial ischaemia occur whenever there is an

imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand .Coronary

atheroma is by far the most common cause of angina.

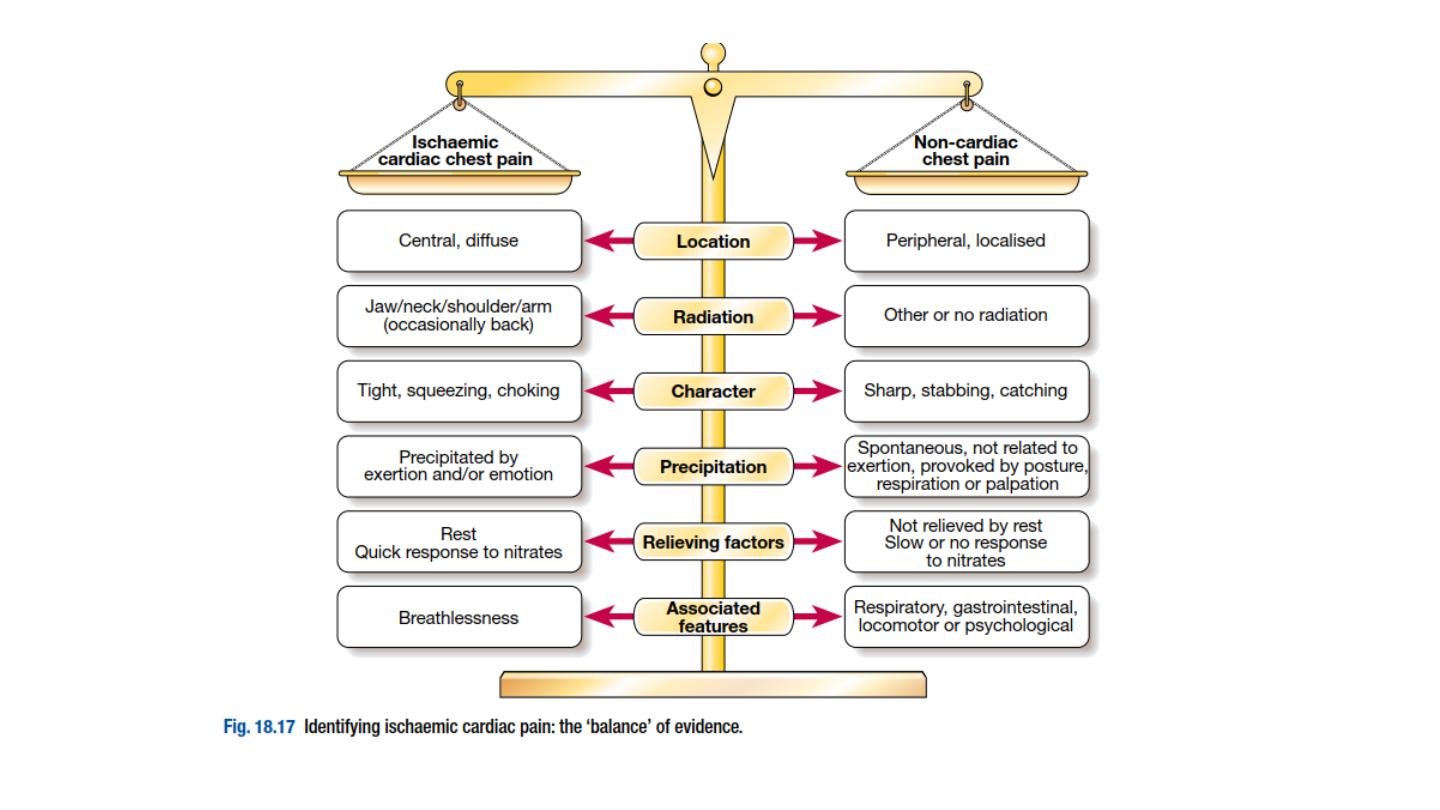

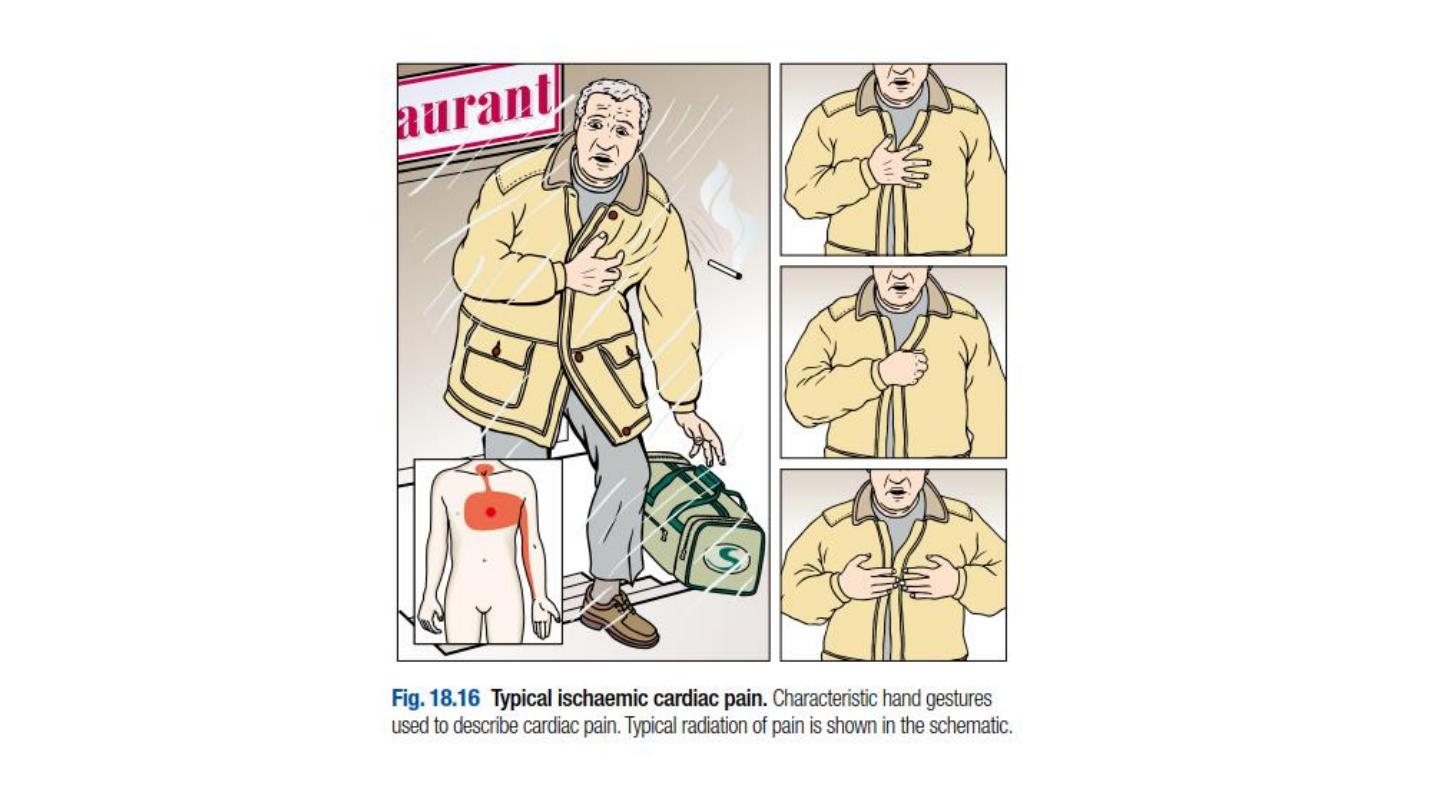

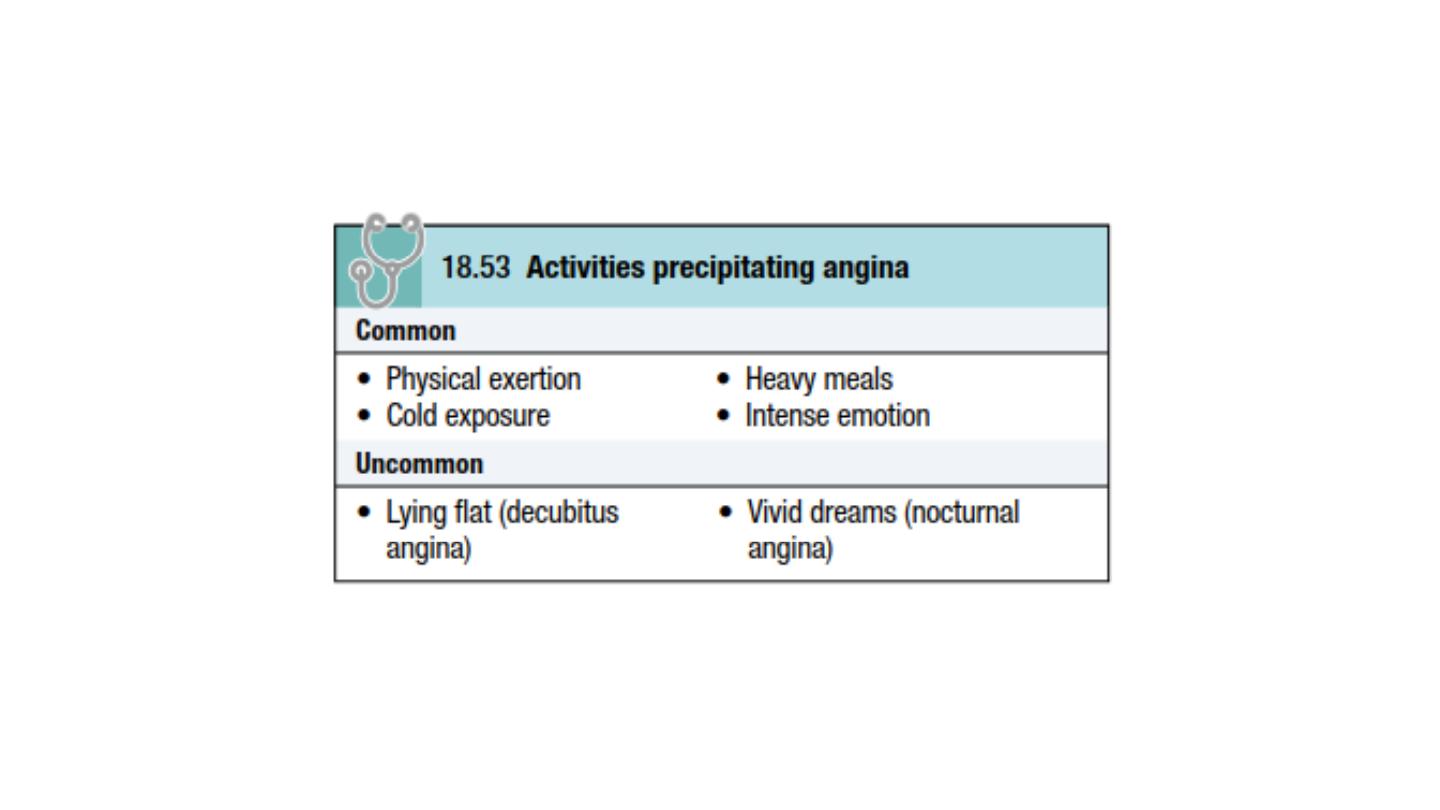

Clinical features

The history is by far the most important factor in making the diagnosis

.Stable angina is characterised by central chest pain, discomfort or

breathlessness that is precipitated by exertion or other forms of stress

important risk factors (e.g. hypertension, diabetes mellitus), left

ventricular dysfunction (cardiomegaly, gallop rhythm), other

manifestations of arterial disease (carotid bruits, peripheral vascular

disease) and unrelated conditions that may exacerbate angina

(anaemia, thyrotoxicosis).

Investigations

Resting ECG

The ECG may show evidence of previous MI but is often normal. Occasionally, there

is T-wave flattening or inversion in some leads, providing non-specific evidence of

myocardial ischaemia or damage. The most convincing ECG evidence of myocardial

ischaemia is the demonstration of reversible ST segment depression or elevation,

with or without T-wave inversion, at the time the patient is experiencing symptoms

(whether spontaneous or induced by exercise testing).

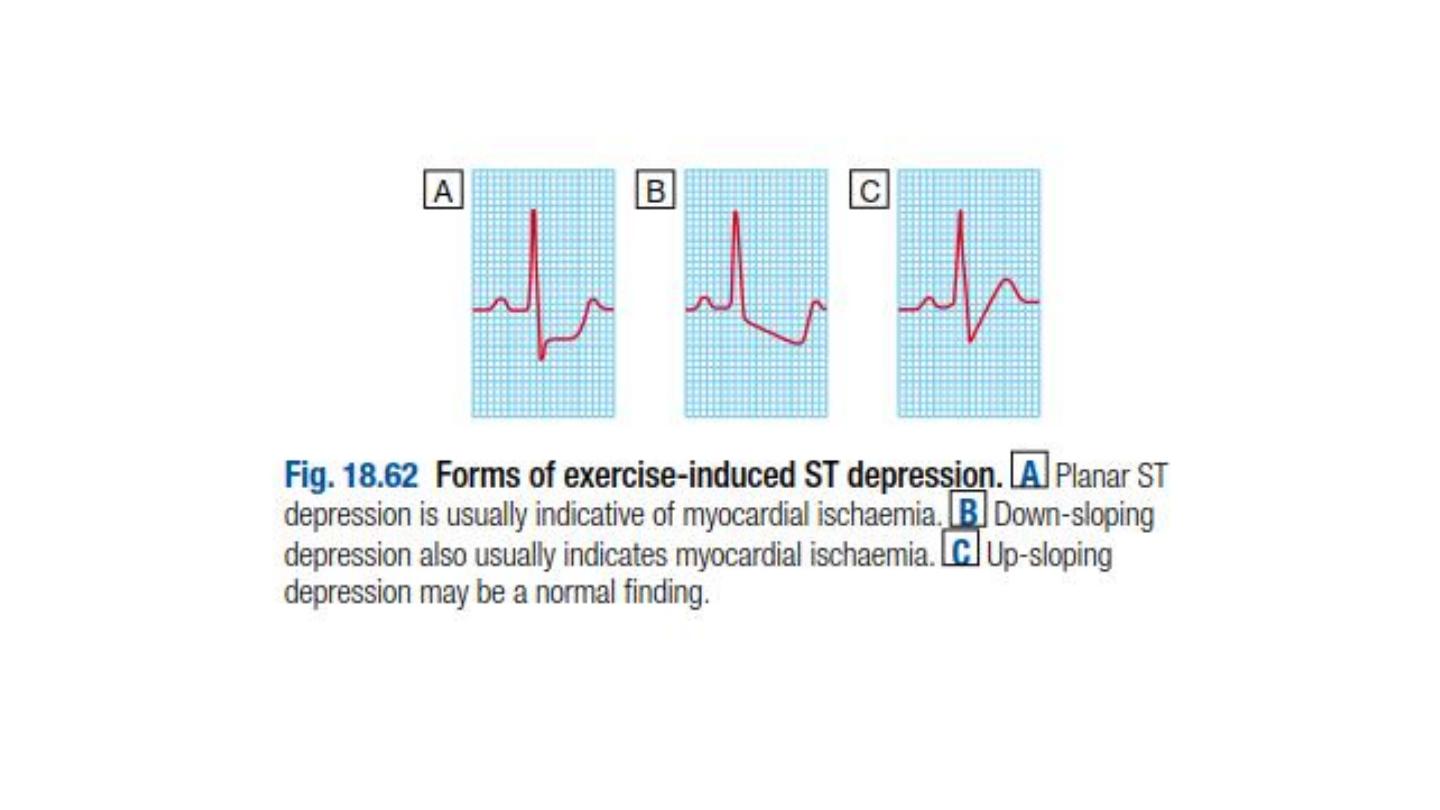

Exercise ECG

An exercise tolerance test (ETT) is usually performed using a standard treadmill or

bicycle ergometer protocol while monitoring the patient’s ECG, BP and general

condition. Planar or down-sloping ST segment depression of ≥ 1 mm is indicative of

ischaemia . Up-sloping ST depression is less specific and often occurs in normal

individuals.

Exercise testing is also a useful means of assessing the severity of coronary disease

and identifying highrisk individuals. For example, the amount of exercise that can

be tolerated and the extent and degree of any ST segment change provide a useful

guide to the likely extent of coronary disease.

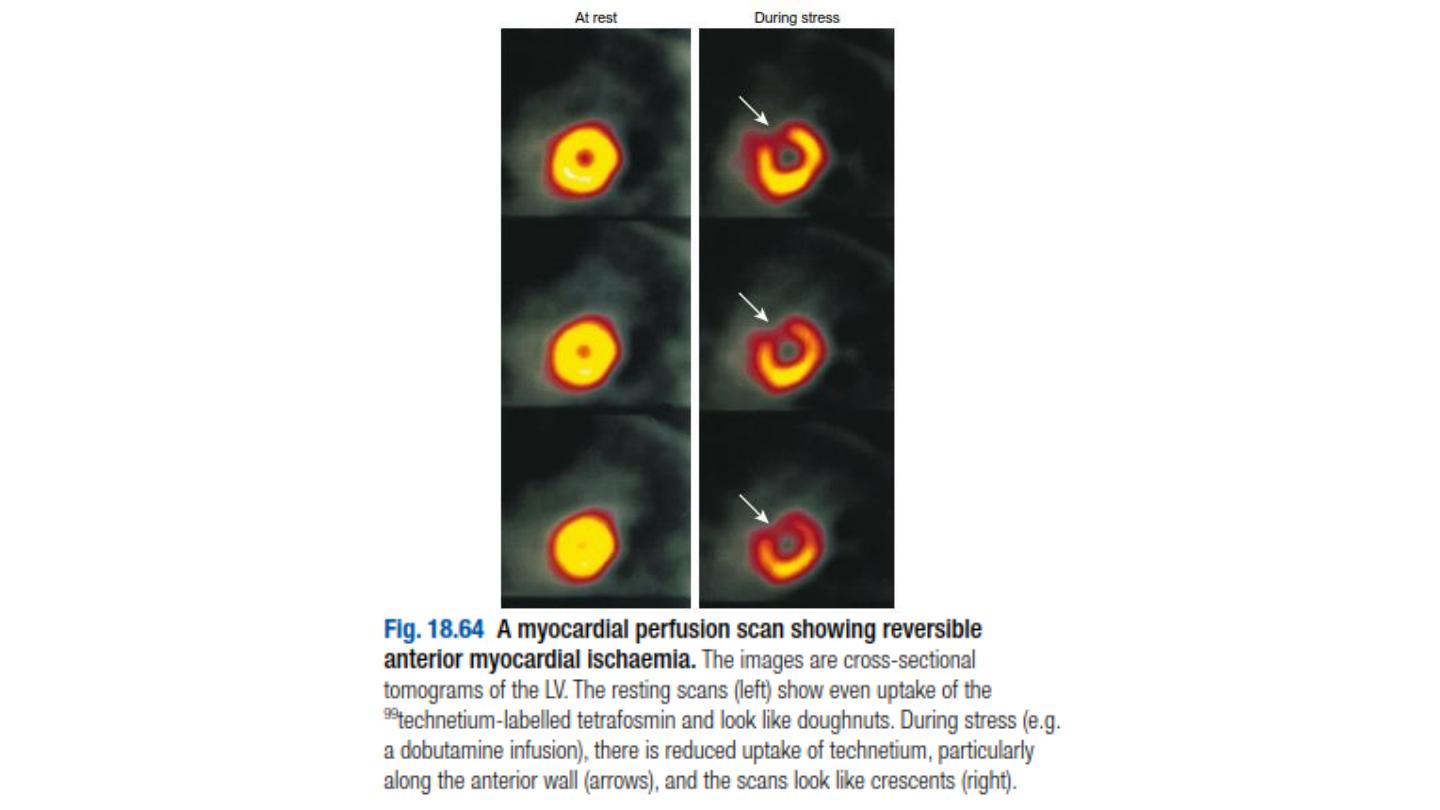

Other forms of stress testing

•

Myocardial perfusion scanning

. This may be helpful in the

evaluation of patients with an equivocal or uninterpretable exercise

test and those who are unable to exercise. It entails obtaining

scintiscans of the myocardium at rest and during stress (either

exercise testing or pharmacological stress, such as a controlled

infusion of dobutamine) after the administration of an intravenous

radioactive isotope, such as

99

technetium tetrofosmin. tetrofosmin

are taken up by viable perfused myocardium. A perfusion defect

present during stress but not at rest provides evidence of reversible

myocardial ischaemia,whereas a persistent perfusion defect seen

during both phases of the study is usually indicative of previous MI.

•

Stress echocardiography

.

This is an alternative to myocardial

perfusion scanning and can achieve similar predictive accuracy. It uses

transthoracic echocardiography to identify ischaemic segments of

myocardium and areas of infarction

Coronary arteriography

This provides detailed anatomical information about the extent and

nature of coronary artery disease ,and is usually performed with a view

to coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery or percutaneous

coronary intervention .In some patients, diagnostic coronary

angiography may be indicated when non-invasive tests have failed to

establish the cause of atypical chest pain. The procedure is performed

under local anesthesia and requires specialized radiological equipment,

cardiac monitoring and an experienced operating team.

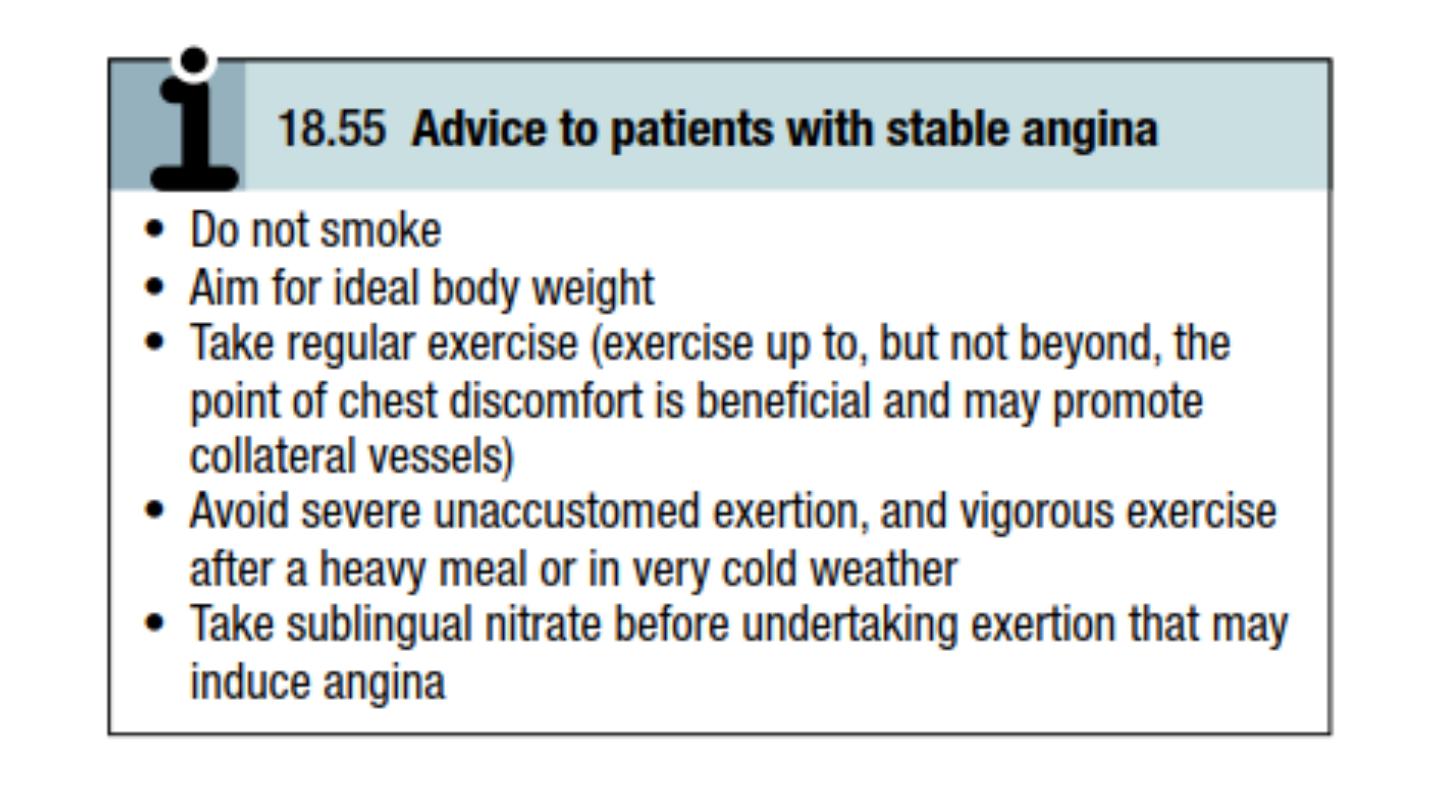

Management: general measures

The management of angina pectoris involves:

• a careful assessment of the likely extent and severity of arterial

disease

• the identification and control of risk factors such as smoking,

hypertension and hyperlipidemia

• the use of measures to control symptoms

• the identification of high-risk patients for treatment to improve life

expectancy.

Management should start with a careful explanation of the problem and

a discussion of the potential lifestyle and medical interventions that may

relieve symptoms and improve prognosis .

Antiplatelet therapy

Low-dose (75 mg) aspirin reduces the risk of adverse events such as MI and should be

prescribed for all patients with coronary artery disease indefinitely . Clopidogrel (75 mg

daily) is an equally effective antiplatelet agent that can be prescribed if aspirin causes

troublesome dyspepsia or other side-effects.

Anti-anginal drug treatment

Five groups of drug are used to help relieve or prevent the symptoms of angina: nitrates, β-

blockers, calcium antagonists, potassium channel activators and an I

f

channel antagonist.

1-

Nitrates

These drugs act directly on vascular smooth muscle to produce venous and arteriolar

dilatation. Their beneficial effects are due to a reduction in myocardial oxygen demand

(lower preload and afterload) and an increase in myocardial oxygen supply (coronary

vasodilatation). Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) administered from a metered-dose

aerosol (400 μg per spray) or as a tablet (300 or 500 μg) will relieve an attack of angina in

2–3 minutes.

Side-effects include headache, symptomatic hypotension and, rarely, syncope.

GTN undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver and is ineffective when

swallowed.

2- Beta-blockers

reducing heart rate, BP and myocardial contractility, but they may provoke

bronchospasm in patients with asthma .slow-release metoprolol 50– 200 mg

daily, bisoprolol 5–15 mg daily. Beta-blockers should not be withdrawn

abruptly because this may have a rebound effect and precipitate dangerous

arrhythmias, worsening angina or MI.

3-

Calcium channel antagonists

reducing BP and myocardial contractility.

Amlodipin 2.5-10mg daily wich is ultra long acting

4-

Potassiu- channel activators

These have arterial and venous dilating properties. Nicorandil (10–30 mg 12-

hourly orally)

5-

I

f

channel antagonist

Ivabradine is the first of this class of drug. It induces bradycardia by

modulating ion channels in the sinus node. In contrast to β-blockers and

rate-limiting calcium antagonists, it does not have other cardiovascular

effects. It appears to be safe to use in patients with heart failure.

• then add a calcium channel antagonist or a long-acting nitrate later if

needed. The goal is the control of angina with minimum side-effects

and the simplest possible drug regimen. There is little evidence that

prescribing multiple anti-anginal drugs is of benefit, and

revascularisation should be considered if an appropriate combination

of two or more drugs fails to achieve an acceptable symptomatic

response.

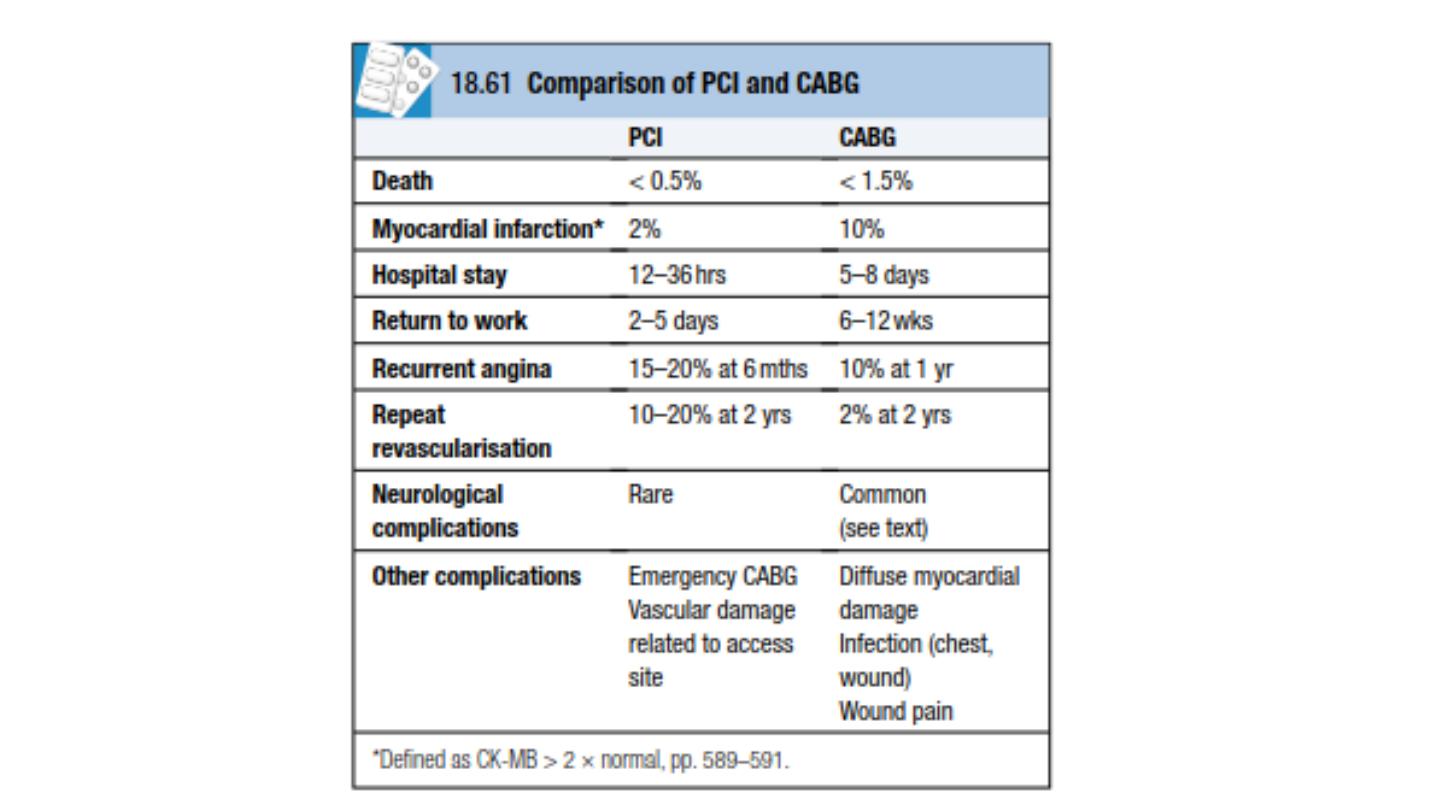

Invasive treatment

•

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)

•

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

Prognosis

• Symptoms are a poor guide to prognosis; nevertheless, the 5-year

mortality of patients with severe angina is nearly double that of

patients with mild symptoms. Exercise testing and other forms of

stress testing are much more powerful predictors of mortality

• In general, the prognosis of coronary artery disease is related to the

number of diseased vessels and the degree of left ventricular

dysfunction,Spontaneous symptomatic improvement due to the

development of collateral vessels is common.

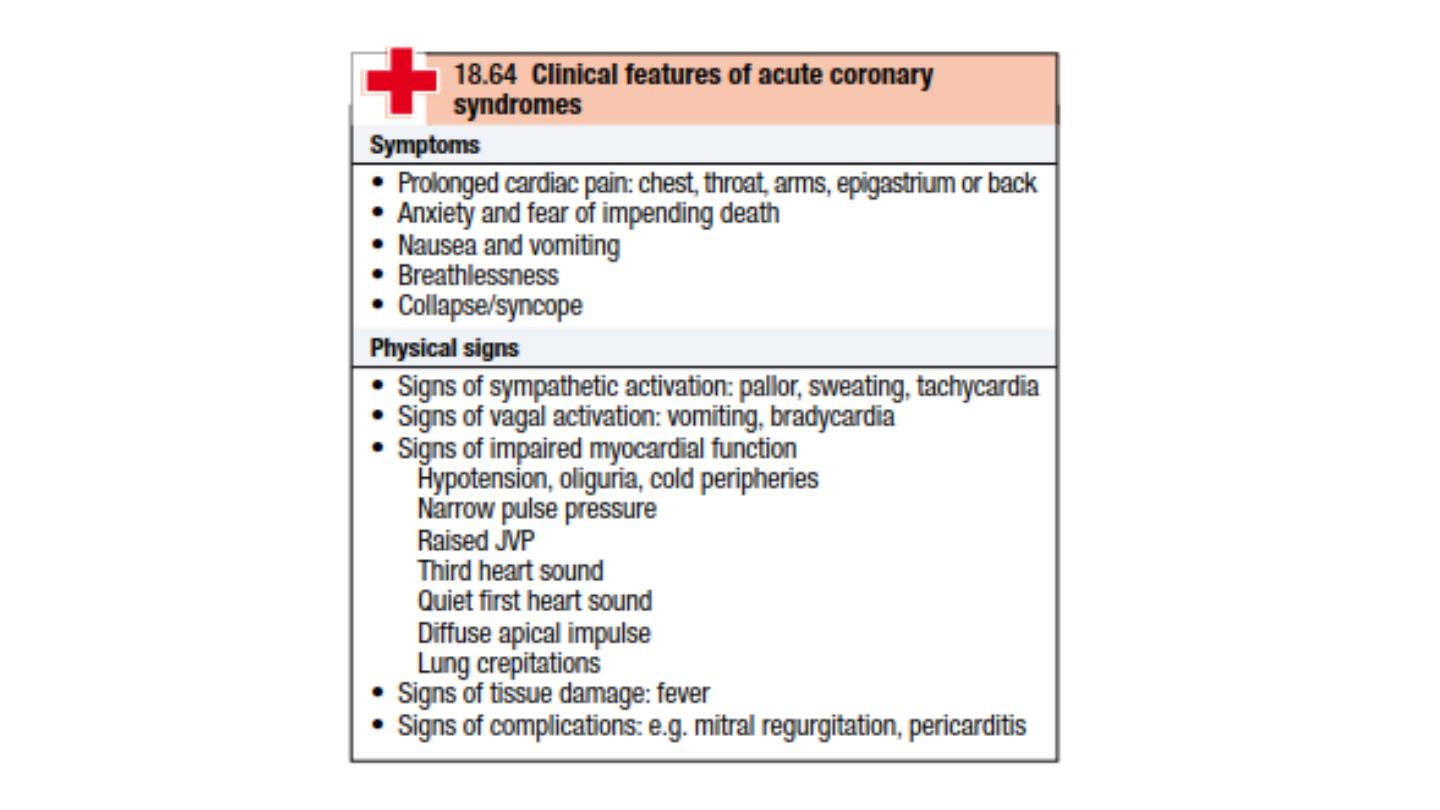

acute coronary syndrome

Acute coronary syndrome is a term that encompasses both unstable angina and MI.

Unstable angina is characterised by new-onset or rapidly worsening angina

(crescendo angina), angina on minimal exertion or angina at rest in the absence of

myocardial damage. In contrast, MI occurs when symptoms occur at rest and there

is evidence of myocardial necrosis, as demonstrated by an elevation in cardiac

troponin or creatine kinase-MB isoenzyme.

An acute coronary syndrome may present as a new phenomenon or against a

background of chronic stable angina. The culprit lesion is usually a complex

ulcerated or fissured atheromatous plaque with adherent plateletrich thrombus

and local coronary artery spasm .This is a dynamic process whereby the degree of

obstruction may either increase, leading to complete vessel occlusion, or regress

due to the effects of platelet disaggregation and endogenous fibrinolysis. In acute

MI, occlusive thrombus is almost alwayspresent at the site of rupture or erosion of

an atheromatous plaque. The thrombus may undergo spontaneous lysis over the

course of the next few days, although by this time irreversible myocardial damage

has occurred. Without treatment, the infarct-related artery remains permanently

occluded in 20–30% of patients. The process of infarction progresses over several

hours and most patients present when it is still possible to salvage myocardium and

improve outcome.

Investigations

Electrocardiography

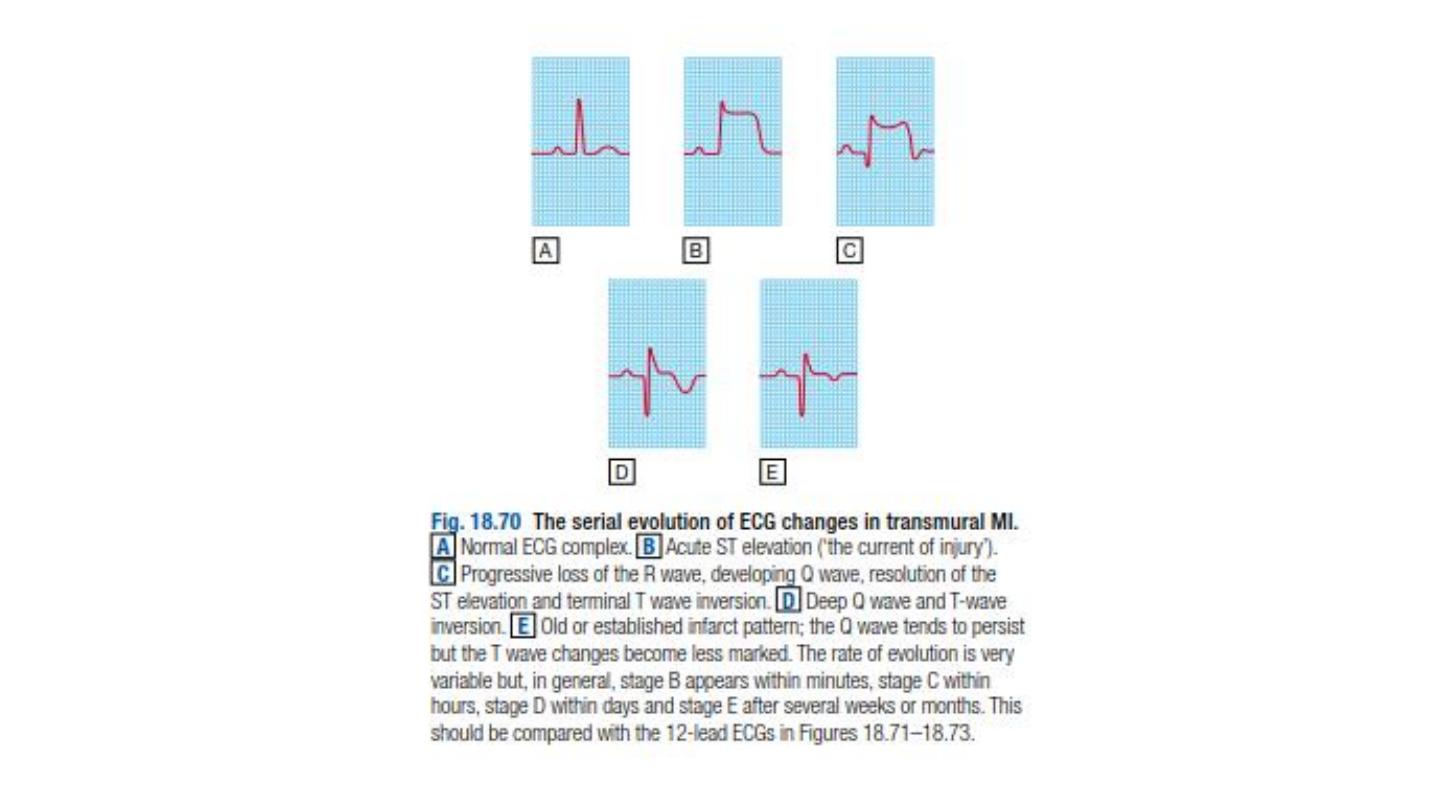

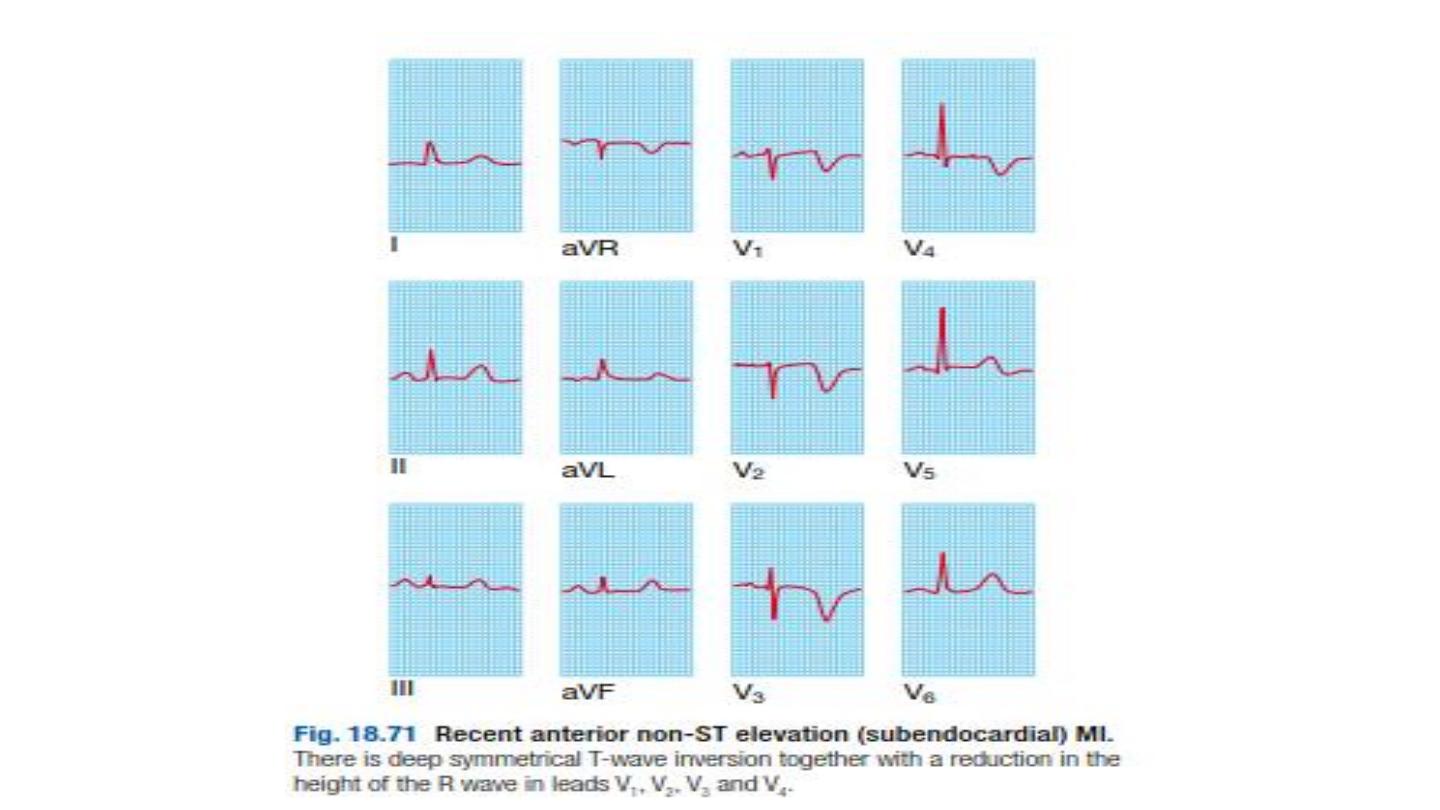

ST-segment elevation (or new bundle branch block) is seen initially with

later diminution in the size of the R wave, and in transmural (full

thickness) infarction, development of a Q wave.

Subsequently, the T wave becomes inverted because of a change in

ventricular repolarisation; this change persists after the ST segment has

returned to normal. These sequential features are sufficiently reliable

for the approximate age of the infarct to be deduced.

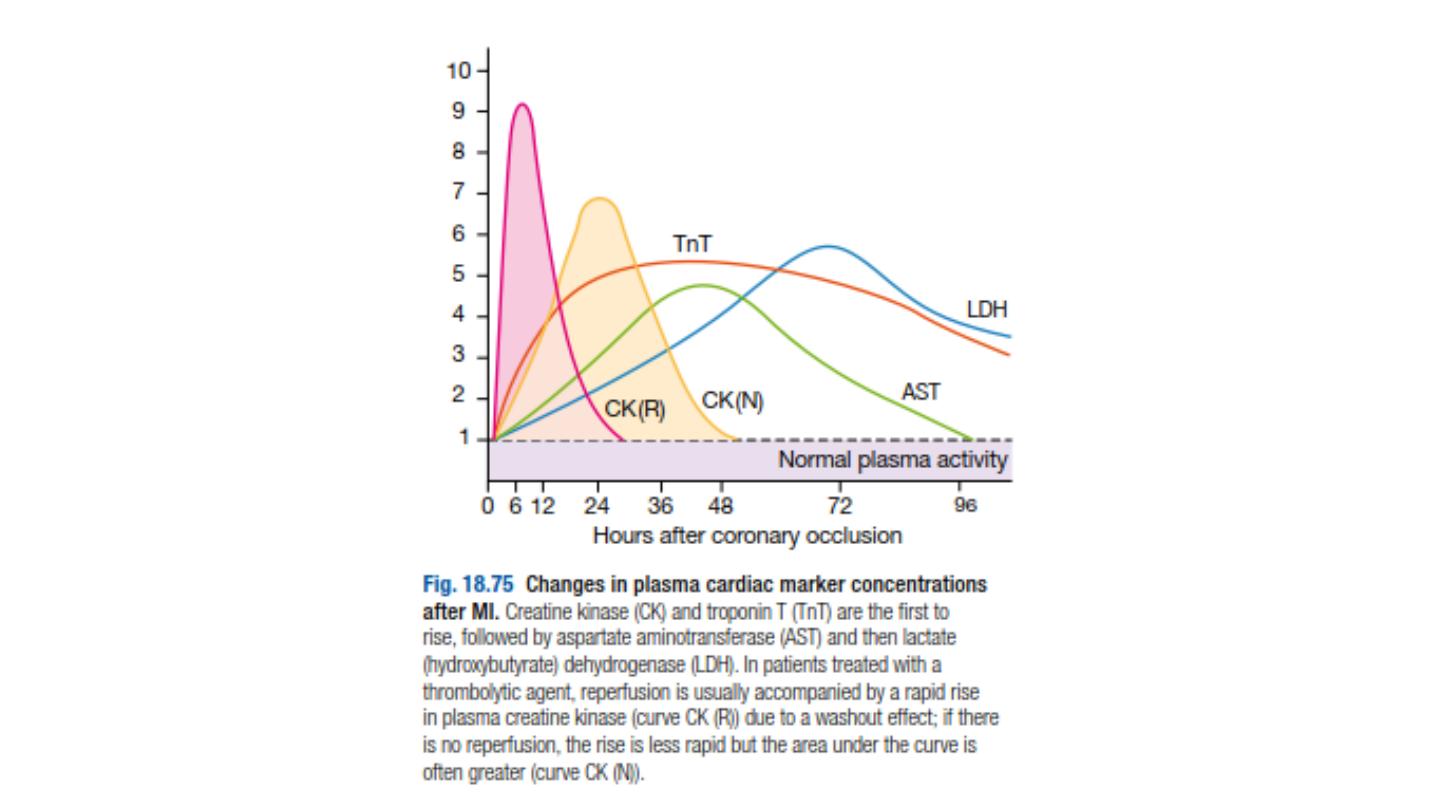

Plasma cardiac markers

These biochemical markers are creatine kinase (CK), a more sensitive

and cardiospecific isoform of this enzyme (CK-MB), and the

cardiospecific proteins, troponins T and I. CK starts to rise at 4–6 hours,

peaks at about 12 hours and falls to normal within 48–72 hours. CK is

also present in skeletal muscle, and a modest rise in CK (but not CK-

MB) may sometimes be due to an intramuscular injection, vigorous

physical exercise or, particularly in older people, a fall. Defibrillation

causes significant release of CK but not CK-MB or troponins. The most

sensitive markers of myocardial cell damage are the cardiac troponins T

and I, which are released within 4–6 hours and remain elevated for up

to 2 weeks.

Other blood tests

A leucocytosis is usual, reaching a peak on the first day. The erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are also elevated.

Chest X-ray

This may demonstrate pulmonary oedema that is not evident on

clinical examination .The heart size is often normal.

This is useful for assessing left and right ventricular function and for

detecting important complications such as mural thrombus, cardiac

rupture, ventricular septal defect, mitral regurgitation and pericardial

effusion.

Management

immediate management: the first 12 hours

Patients should be admitted urgently to hospital because there is a

significant risk of death or recurrent myocardial ischaemia during the

early unstable phase, and appropriate medical therapy can reduce the

incidence of these by at least 60%.

•

Analgesia

Adequate analgesia is essential not only to relieve distress, but also to

lower adrenergic drive and thereby reduce vascular resistance, BP,

infarct size and susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias. Intravenous

opiates (initially morphine sulphate 5–10 mg or diamorphine 2.5–5 mg)

and antiemetics (initially metoclopramide 10 mg) should be

administered

•

Antithrombotic therapy

•

Antiplatelet therapy

In patients with acute coronary syndrome, oral administration of 75–300 mg

aspirin daily improves survival, with a 25% relative risk reduction in

mortality. The first tablet (300 mg) should be given orally within the first 12

hours and therapy should be continued indefinitely if there are no side-

effects. In combination with aspirin, the early (within 12 hours) use of

clopidogrel 600 mg, followed by 150 mg daily for 1 week and 75 mg daily

thereafter, ticagrelor (180 mg followed by 90 mg 12-hourly) is more effective

than clopidogrel in reducing vascular death, MI or stroke, and all-cause death

without affecting overall major bleeding risk.

•

Anticoagulants

Anticoagulation can be achieved using unfractionated heparin, fractioned

(low molecular weight) heparin. with low molecular weight heparin

(subcutaneous enoxaparin 1 mg/kg 12-hourly) being a reasonable

alternative. Anticoagulation should be continued for 8 days or until discharge

from hospital or coronary revascularisation.

•

Anti-anginal therapy

Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (300–500 μg) is a valuable first-aid

measure in unstable angina or threatened infarction, and intravenous

nitrates (GTN 0.6–1.2 mg/ hour or isosorbide dinitrate 1–2 mg/hour)

are useful for the treatment of left ventricular failure and the relief of

recurrent or persistent ischaemic pain.

Intravenous β-blockers (e.g. atenolol 5–10 mg or metoprolol 5–15 mg

given over 5 mins) relieve pain, reduce arrhythmias and improve short-

term mortality in patients who present within 12 hours of the onset of

symptoms

A dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonist (e.g. nifedipine or

amlodipine) can be added to the β-blocker

•

Reperfusion therapy

Non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

Immediate emergency reperfusion therapy has no demonstrable benefit in

patients with non-ST segment elevation MI and thrombolytic therapy may be

harmful.

ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

Immediate reperfusion therapy restores coronary artery patency, preserves

left ventricular function and improves survival. Successful therapy is

associated with pain relief, resolution of acute ST elevation and sometimes

transient arrhythmias (e.g. idioventricular rhythm).

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

This is the treatment of

choice for ST segment elevation. Outcomes are best when it is used in

combination with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists and

intracoronary stent implantation. When primary PCI cannot be achieved

within 2 hours of diagnosis, thrombolytic therapy should be administered.

Thrombolysis.

Alteplase (human tissue plasminogen activator or tPA) is given

over 90 minutes (bolus dose of 15 mg, followed by 50 mg, over 30 mins and

then 35 mg, over 60 mins). Its use is associated with better survival rates

than other thrombolytic agents, such as strepto-kinase, but carries a slightly

higher risk of intracerebralbleeding

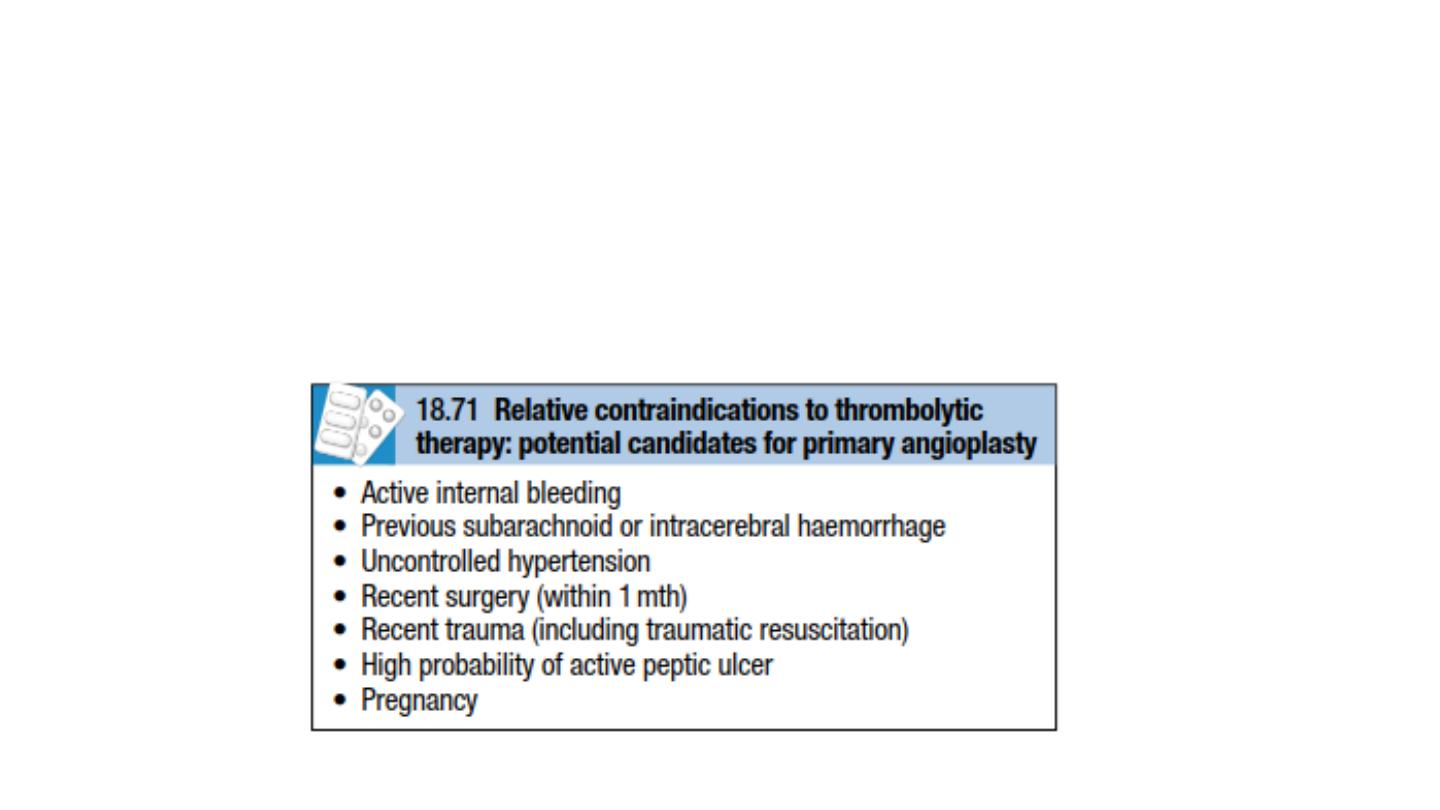

• The major hazard of thrombolytic therapy is bleeding. Cerebral

haemorrhage ,the treatment should be withheld if there is a

significant risk of serious bleeding.

• For some patients, thrombolytic therapy is contra-indicated or fails to

achieve coronary arterial reperfu-sion .Early emergency PCI may then

be considered, particularly where there is evidence of cardiogenic

shock.

Complications of acute coronary syndrome

•

Arrhythmias

•

Ventricular fibrillation

•

Atrial fibrillation

•

Acute circulatory failure

•

Pericarditis

•

Bradycardia

•

Ischaemia

•

Embolism

•

Impaired ventricular function, remodelling and ventricular

aneurysm

•

Mechanical complications

Part of the necrotic muscle in a fresh infarct may tear or rupture, with

devastating consequences:

Rupture of the papillary muscle

can cause acute pulmonary oedema and

shock due to the sudden onset of severe mitral regurgitation, which presents

with a pansystolic murmur and third heart sound.

In the presence of severe valvular regurgitation, the murmur may be quiet or

absent. The diagnosis is confirmed by echocardiography and emergency

mitral valve replacement may be necessary. Lesser degrees of mitral

regurgitation due to papillary muscle dysfunction are common and may be

transient.

Rupture of the interventricular septum

causes left-to-right shunting through

a ventricular septal defect. This usually presents with sudden haemodynamic

deterioration accompanied by a new loud pansystolic murmur radiating to

the right sternal border

Rupture of the ventricle

may lead to cardiac tamponade and is usually

Later in-hospital management

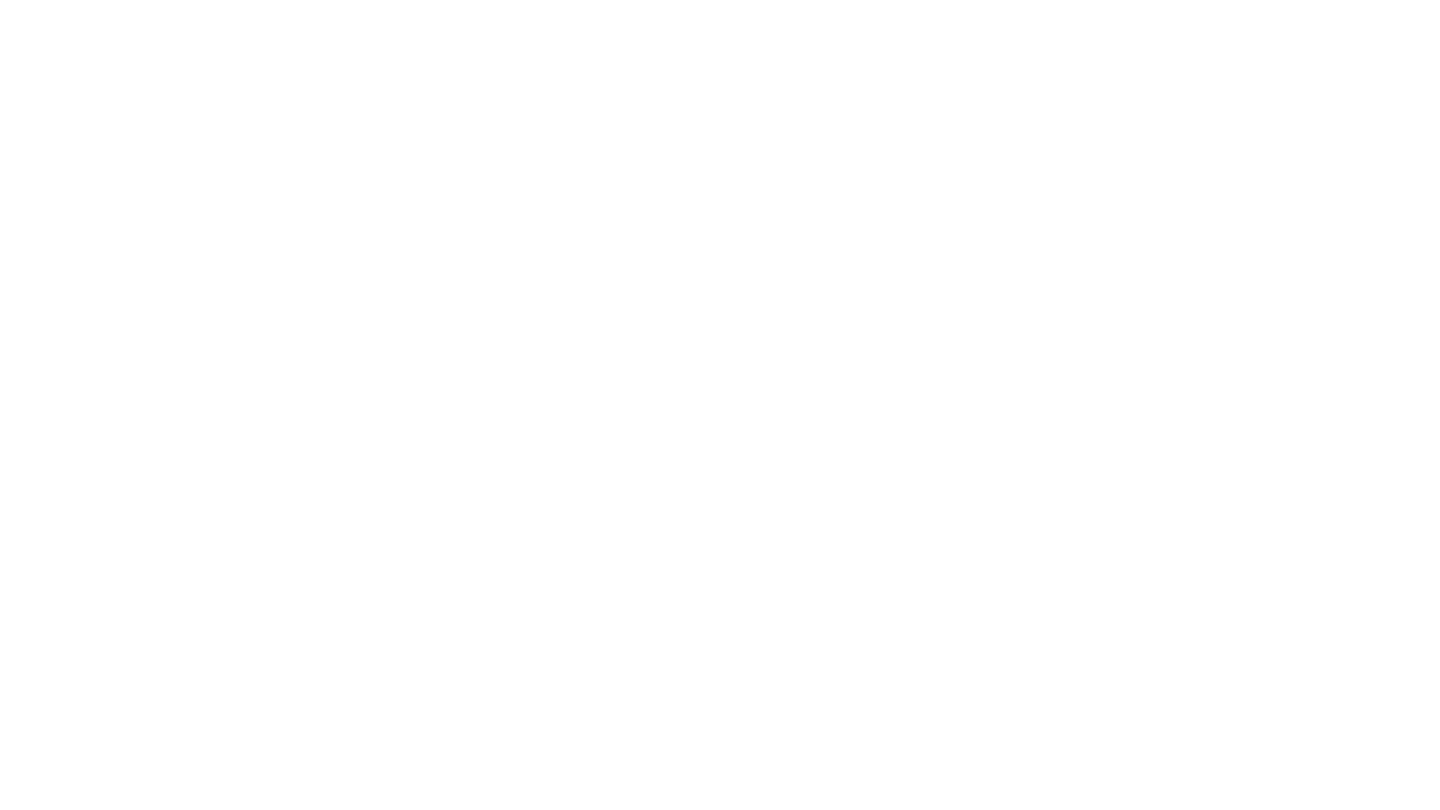

Secondary prevention drug therapy

*Aspirin and clopidogrel

*Beta-blockers

*Continuous treatment with an oral β-blocker

*ACE inhibitors

• patients with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction and those with

preserved left ventricular function. They should therefore be considered in all

patients with acute coronary syndrome. Caution must be exercised in

hypovolaemic or hypotensive patients because the introduction of an ACE

inhibitor may exacerbate hypotension and impair coronary perfusion. In patients

intolerant of ACE inhibitor therapy, angiotensin receptor blockers (e.g. valsartan

40–160 mg 12-hourly or candesartan 4–16 mg daily) are suitable alternatives and

are better tolerated.

• Patients with acute MI and left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction < 35%)

and either pulmonary oedema or diabetes mellitus further benefit from

additional aldosterone receptor antagonism (e.g. eplerenone 25–50 mg daily).

•

Device therapy

Implantable cardiac defibrillators are of benefit in preventing sudden

cardiac death in patients who have severe left ventricular impairment

(ejection fraction ≤ 30%) after MI.

Prognosis

In almost one-quarter of all cases of MI, death occurs within a few minutes

without medical care. Half the deaths occur within 24 hours of the onset of

symptoms and about 40% of all affected patients die within the first month.

The prognosis of those who survive to reach hospital is much better, with a

28-day survival of more than 85%. Patients with unstable angina have a

mortality approximately half those with MI.

Early death is usually due to an arrhythmia and is independent of the extent

of MI. However, late outcomes are determined by the extent of myocardial

damage and unfavourable features include poor left ventricular function, AV

block and persistent ventricular arrhythmias. The prognosis is worse for

anterior than for inferior infarcts. Bundle branch block and high cardiac

marker levels both indicate extensive myocardial damage. Old age,

depression and social isolation are also associated with a higher mortality.

Of those who survive an acute attack, more than 80% live for a further year,

about 75% for 5 years, 50% for 10 years and 25% for 20 years.

Mitral valve prolapse

This is also known as ‘floppy’ mitral valve and is one of the more

common causes of mild mitral regurgitation .It is caused by congenital

anomalies or degenerative myxomatous changes, and is sometimes a

feature of connective tissue disorders such as Marfan’s syndrome.

In its mildest forms, the valve remains competent but bulges back into

the atrium during systole, causing a midsystolic click but no murmur. A

click is not always audible and the physical signs may vary with both

posture and respiration.

Progressive elongation of the chordae tendineae leads to increasing

mitral regurgitation, and if chordal rupture occurs, regurgitation

suddenly becomes severe. This is rare before the fifth or sixth decade

of life.

Clinical features

• Mitral valve prolapse is associated with arrhythmias, atypical chest

pain and a very small risk of embolic stroke or TIA, the overall long-

term prognosis is good.

• Progressive elongation of the chordae tendineae leads to symtoms of

mitral regurgitation and then the clinical features of mitral

regurgitation will appear.

Prevention

• You can't prevent mitral valve prolapse. However, you can lower your

chances of developing the complications associated with it by making

sure you take your medications

Acute pericarditis

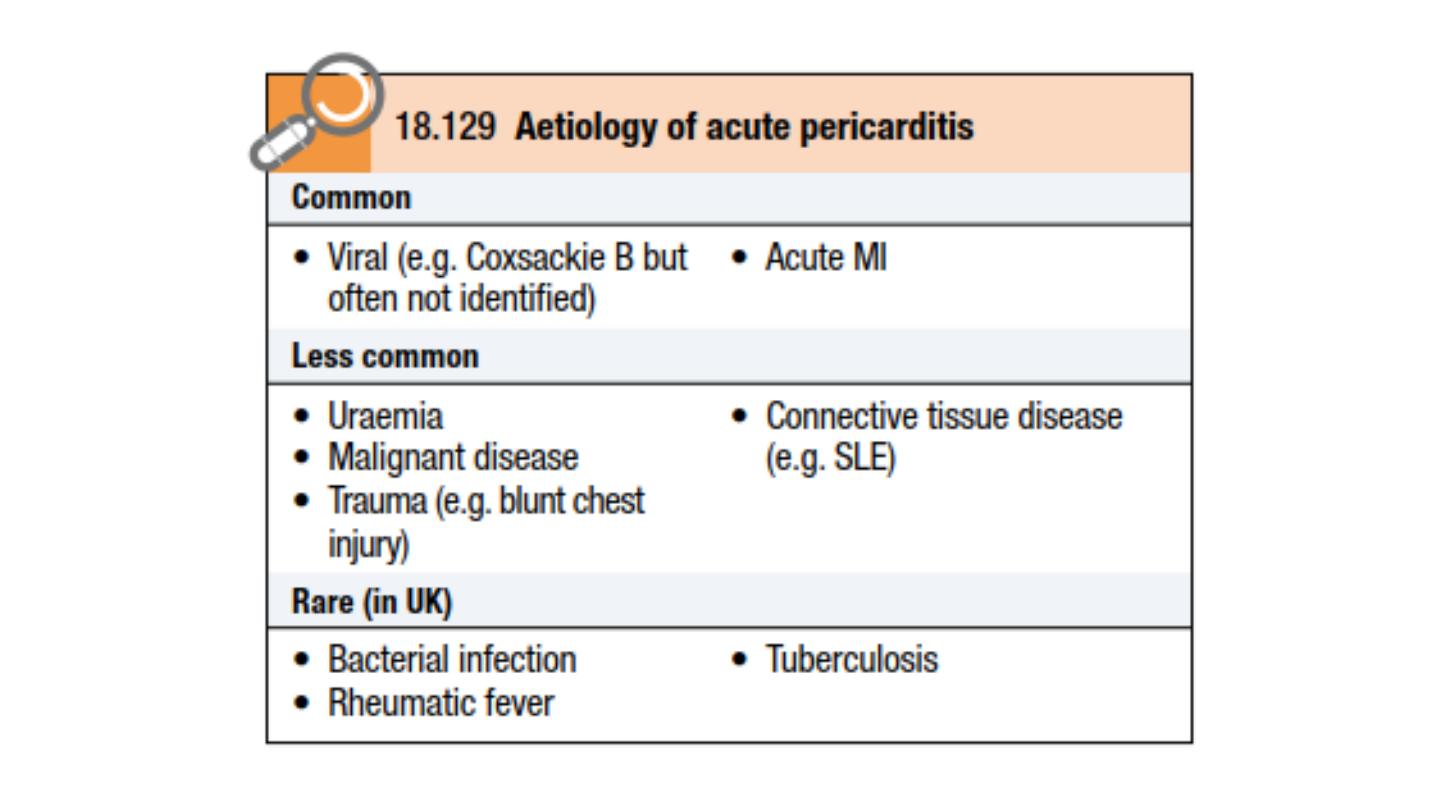

Aetiology

• Pericarditis and myocarditis often coexist, and all forms of pericarditis may

produce a pericardial effusion that, depending on the aetiology, may be

fibrinous, serous, haemorrhagic or purulent.

• A fibrinous exudate may eventually lead to varying degrees of adhesion

formation

• Serous pericarditis often produces a large effusion of turbid, strawcoloured

fluid with a high protein content.

• A haemorrhagic effusion is often due to malignant disease, particularly

carcinoma of the breast or bronchus, and lymphoma.

• Purulent pericarditis is rare and may occur as a complication of

septicaemia, by direct spread from an intra-thoracic infection, or from a

penetrating injury.

Clinical features

• The characteristic pain of pericarditis is retrosternal, radiates to the shoulders and neck,

and is typically aggravated by deep breathing, movement, a change of position, exercise

and swallowing. A low-grade fever is common.

• A pericardial friction rub is a high-pitched superficial scratching or crunching noise

produced by movement of the inflamed pericardium and is diagnostic of pericarditis

Investigations and management

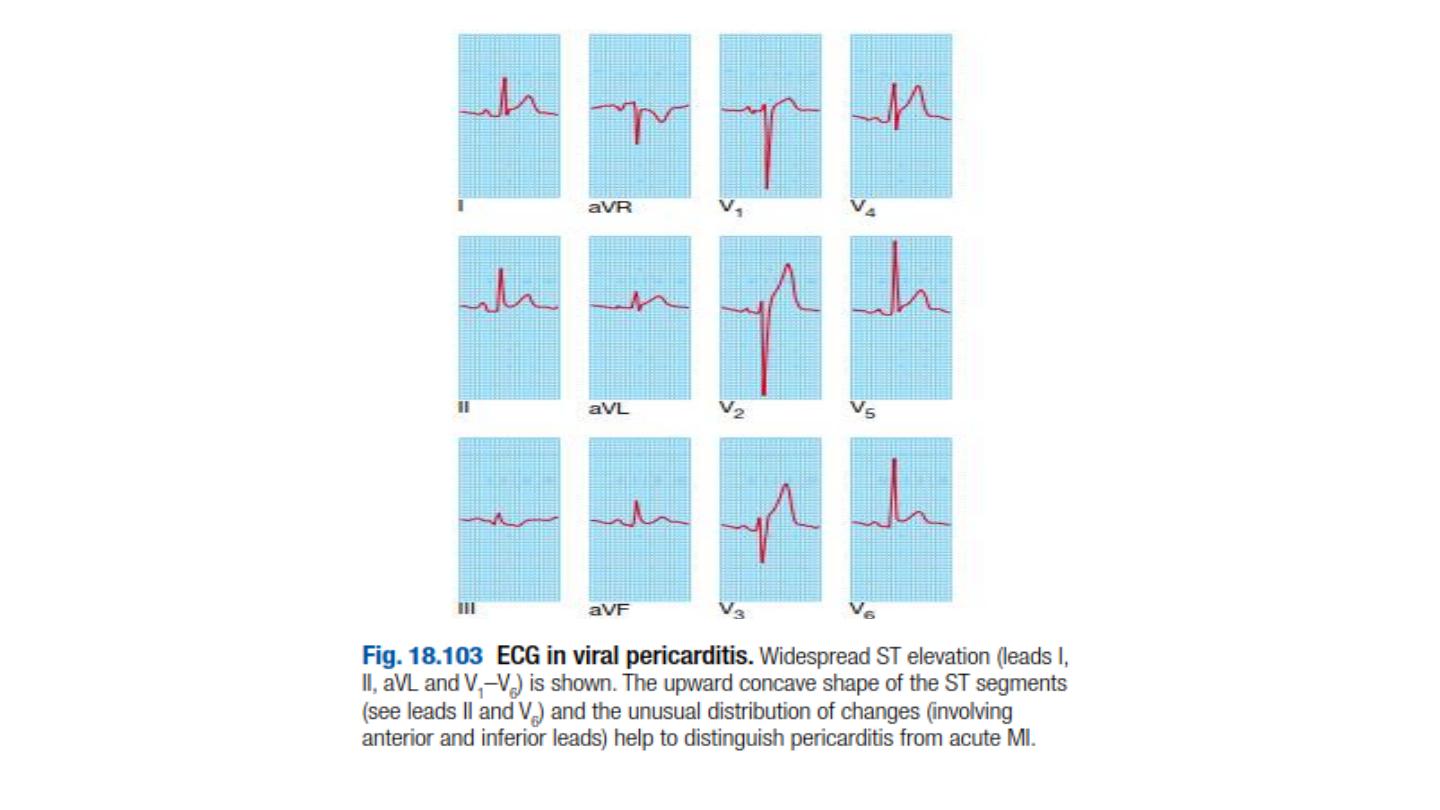

• The ECG shows ST elevation with upward concavity over the affected area, which may be

widespread. PR interval depression is a very specific indicator of acute pericarditis. Later,

there may be T-wave inversion, particularly if there is a degree of myocarditis.

• The pain is usually relieved by aspirin (600 mg 4-hourly) but a more potent anti-

inflammatory agent such as indometacin (25 mg 8-hourly) may be required.

Corticosteroids may suppress symptoms but there is no evidence that they accelerate

cure.

• In viral pericarditis, recovery usually occurs within a few days or weeks but there may be

recurrences (chronic relapsing pericarditis). Purulent pericarditis requires treatment with

antimicrobial therapy, pericardiocentesis and, if necessary, surgical drainage.

Aortic dissection

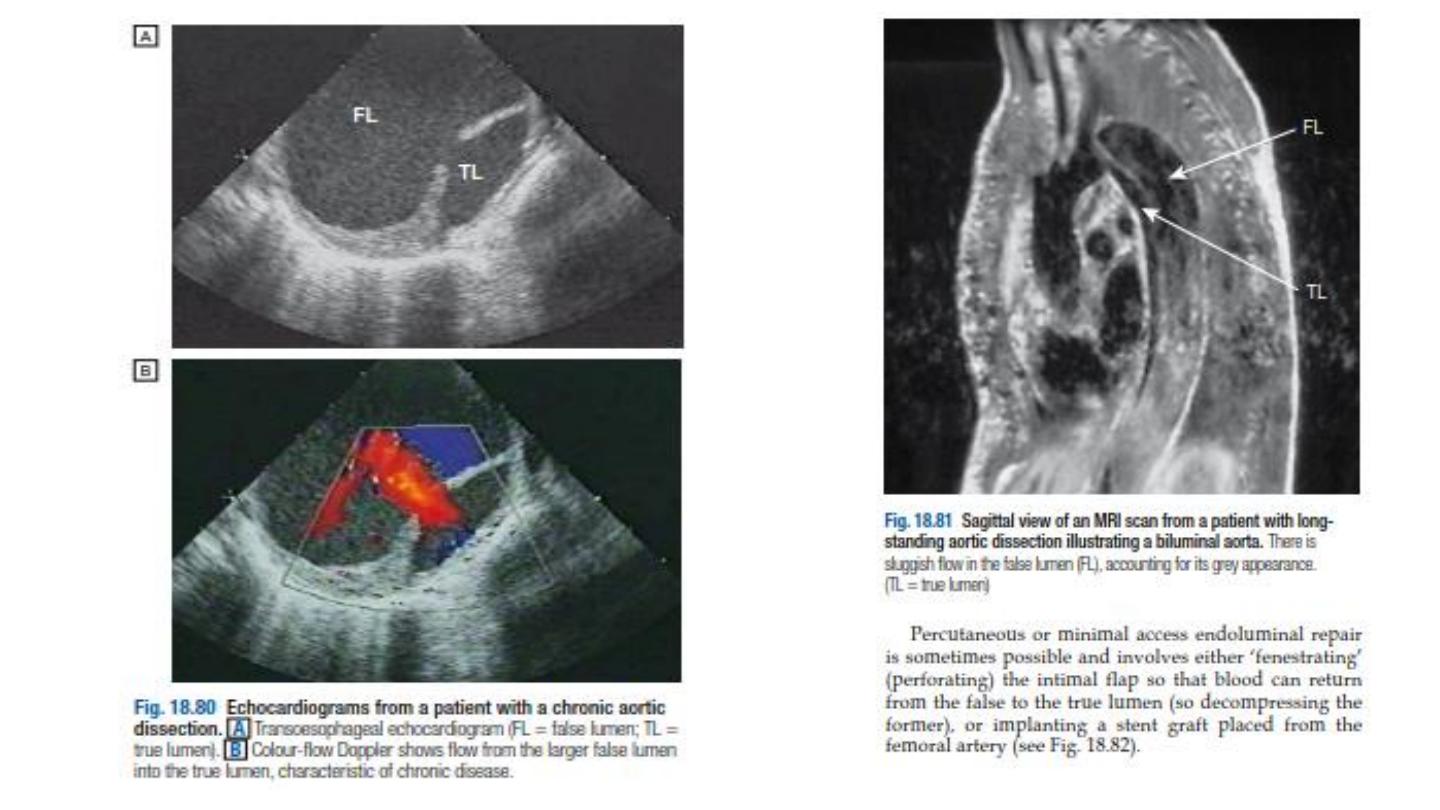

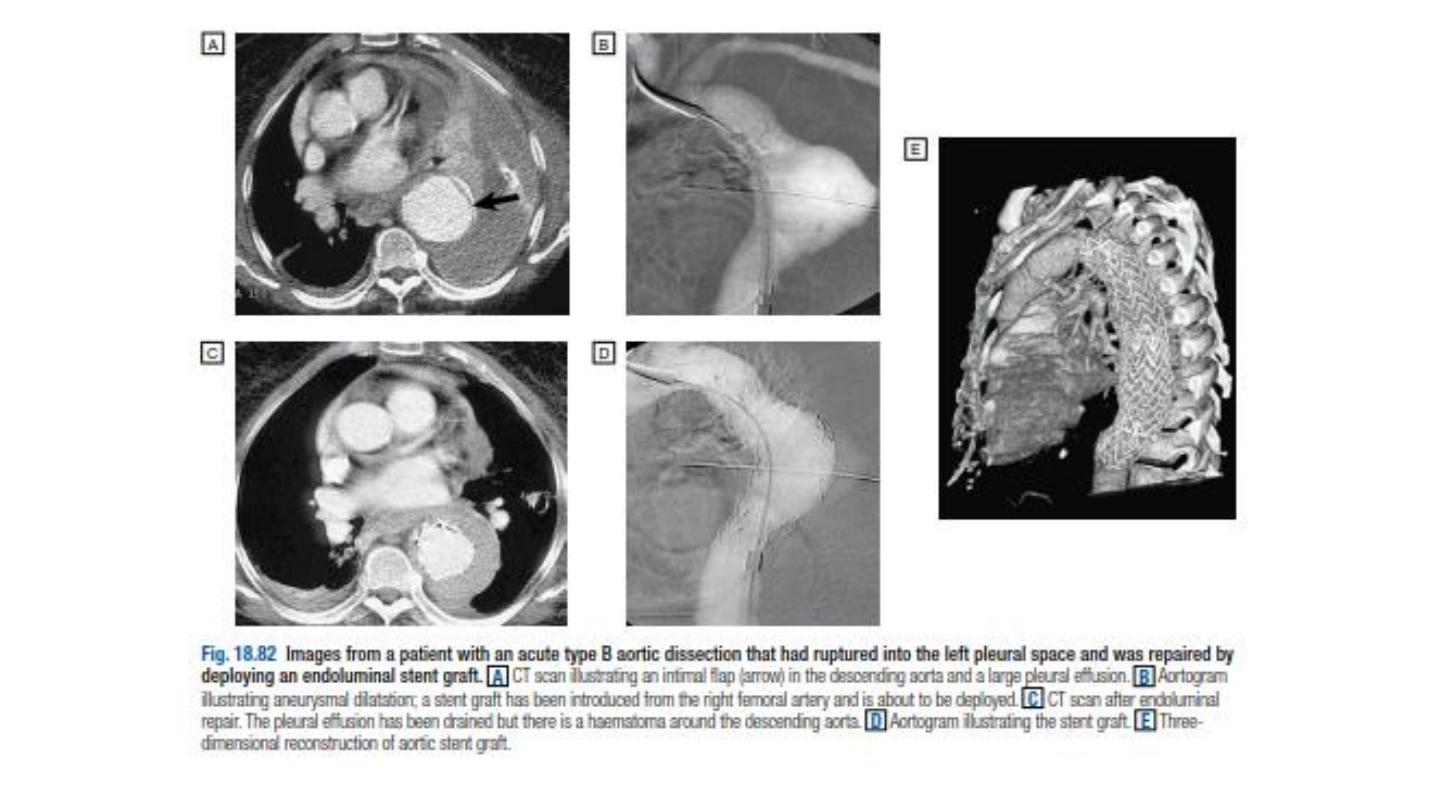

• A breach in the integrity of the aortic wall allows arterial blood to

enter the media, which is then split into two layers, creating a ‘false

lumen’ alongside the existing or ‘true lumen’ .The aortic valve may be

damaged and the branches of the aorta may be compromised.

Typically, the false lumen eventually re-enters the true lumen,

creating a double-barrelled aorta, but it may also rupture into the left

pleural space or pericardium with fatal consequences.

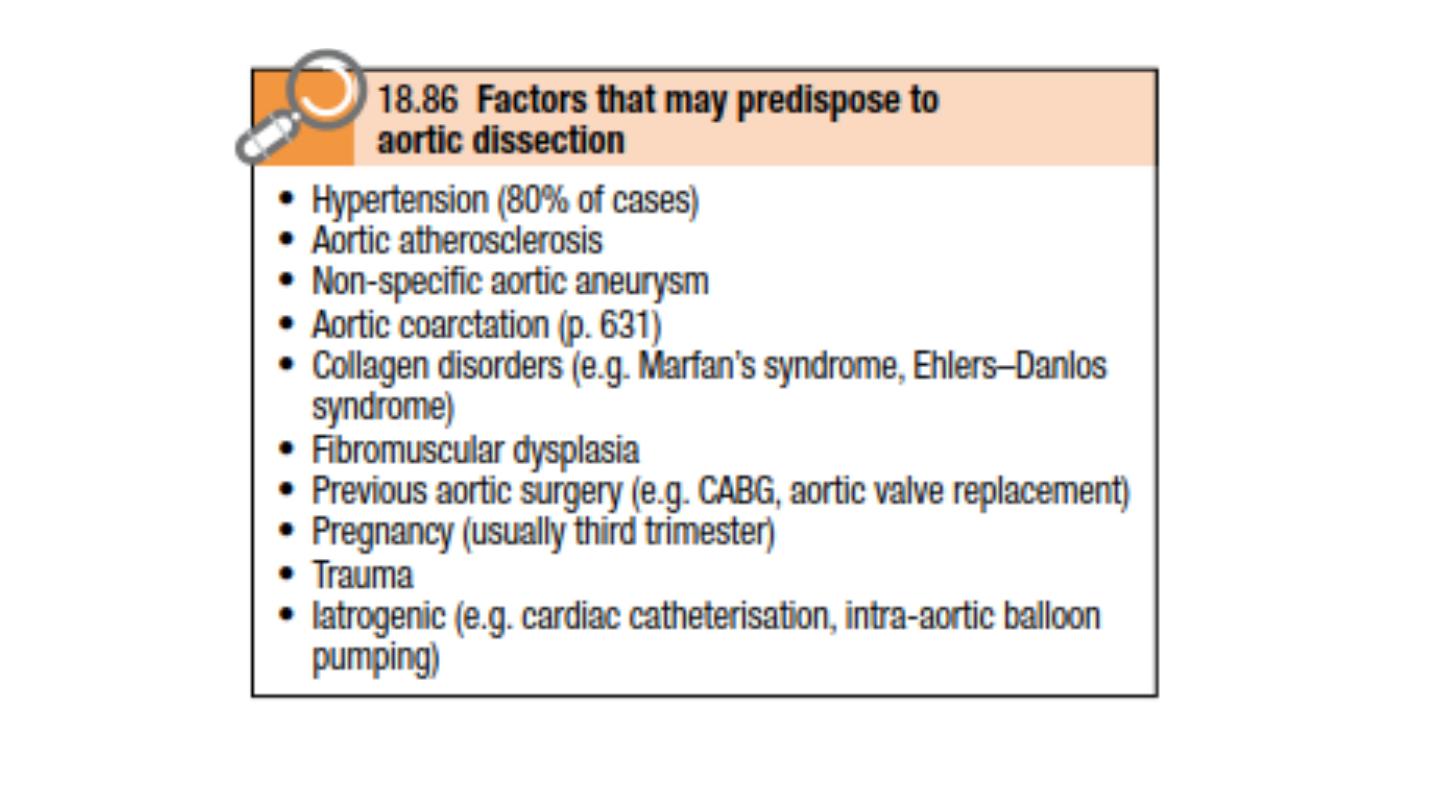

• Disease of the aorta and hypertension are the most important

aetiological factors but a variety of other conditions may be

implicated .Chronic dissections may lead to aneurysmal dilatation of

the aorta, and thoracic aneurysms may be complicated by dissection.

It is therefore sometimes difficult to identify the primary pathology.

• The peak incidence is in the sixth and seventh decades of life but

dissection can occur in younger patients, most commonly in

association with Marfan’s syndrome, pregnancy or trauma; men are

twice as frequently affected as women.

• Aortic dissection is classified anatomically and for management

purposes into type A and type B ,involving or sparing the ascending

aorta respectively. Type A dissections account for two-thirds of cases

and frequently also extend into the descending aorta.

•

Clinical features

• Involvement of the ascending aorta typically gives rise to

• anterior chest pain, and involvement of the descending aorta to

intrascapular pain. The pain is typically described as ‘tearing’ and very

abrupt in onset.

• collapse is common. Unless there is major haemorrhage, the patient

is invariably hypertensive.

• There may be asymmetry of the brachial, carotid or femoral pulses

and signs of aortic regurgitation.

• Occlusion of aortic branches may cause MI (coronary), stroke (carotid)

paraplegia (spinal), mesenteric infarction with an acute abdomen

(coeliac and superior mesenteric), renal failure (renal) and acute limb

(usually leg) ischaemia.

Investigations

• The chest X-ray characteristically shows broadening of the upper

mediastinum and distortion of the aortic, A left-sided pleural effusion is

common.

• The ECG may show left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with

hypertension, or rarely changes of acute MI (usually inferior).

• Doppler echocardiography may show aortic regurgitation, a dilated aortic

root and, occasionally, the flap of the dissection.

• Transoesophageal echocardiography is particularly helpful because

transthoracic echocardiography can only image the first 3–4 cm of the

ascending aorta .CT and MRI angiogra-phy are both highly specific and

sensitive.

Management

• Initial management comprises pain control and antihypertensive

treatment.

• Type A dissections require emergency surgery to replace the ascending

aorta. Type B aneurysms are treated medically unless there is actual or

impending external rupture, or vital organ (gut, kidneys) or limb ischaemia,

as the morbidity and mortality associated with surgery is very high. The

aim of medical management is to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP)

of 60–75 mmHg to reduce the force of the ejection of blood from the LV.

• First-line therapy is with β-blockers; the additional α-blocking properties of

labetalol make it especially useful.

• Rate-limiting calcium channel blockers, such as verapamil or diltiazem, are

used if β-blockers are contraindicated. Sodium nitroprusside

• may be considered if these fail to control BP adequately.