Target organ damage

The adverse effects of hypertension on the organs can often be detected clinically.Blood vessels

In larger arteries (> 1 mm in diameter), the internal elastic lamina is thickened, smooth muscle is hypertrophied and fibrous tissue is deposited. The vessels dilate and become tortuous, and their walls become less compliant.

In smaller arteries (< 1 mm), hyaline arteriosclerosis occurs in the wall, the lumen narrows and aneurysms may develop. Widespread atheroma develops and may lead to coronary and cerebrovascular disease, particularly if other risk factors (e.g. smoking, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes) are present.

Hypertension is a major risk factor in the pathogenesis of aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection.

Central nervous system

Stroke is a common complication of hypertension and may be due to cerebral haemorrhage or infarction.

Carotid atheroma and transient ischaemic attacks are more common in hypertensive patients. Subarachnoid haemorrhage is also associated with hypertension.

Hypertensive encephalopathy is a rare condition characterised by high BP and neurological symptoms, including transient disturbances of speech or vision, paraesthesiae, disorientation, fits and loss of consciousness. Papilloedema is common. A CT scan of the brain often shows haemorrhage in and around the basal ganglia; however, the neurological deficit is usually reversible if the hypertension is properly controlled.

Retina

The optic fundi reveal a gradation of changes linked to the severity of hypertension; fundoscopy can, therefore, provide an indication of the arteriolar damage occurring elsewhere ‘ Cotton wool’ exudates are associated with retinal ischaemia or infarction, and fade in a few weeks ‘Hard’ exudates (small, white, dense deposits of lipid) and microaneurysms (‘dot’ haemorrhages( are more characteristic of diabetic retinopathy

Hypertension is also associated with central retinal vein thrombosis.

Heart

The excess cardiac mortality and morbidity associated with hypertension are largely due to a higher incidence of coronary artery disease. High BP places a pressure load on the heart and may lead to left ventricular hypertrophy with a forceful apex beat and fourth heart sound. ECG or echocardiographic evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy is highly predictive of cardiovascular complications and therefore particularly useful in risk assessment.

Atrial fibrillation is common and may be due to diastolic dysfunction caused by left ventricular hypertrophy or the effects of coronary artery disease.

Severe hypertension can cause left ventricular failure in the absence of coronary artery disease, particularly when renal function, and therefore sodium excretion, is impaired

Kidneys

Long-standing hypertension may cause proteinuria and progressive renal failure by damaging the renal vasculature.

‘Malignant’ or ‘accelerated’ phase hypertension

This rare condition may complicate hypertension of any aetiology and is characterised by accelerated microvascular damage with necrosis in the walls of small arteries and arterioles (‘fibrinoid necrosis’) and by intravascular thrombosis. The diagnosis is based on evidence of high BP and rapidly progressive end organ damage, such as retinopathy (grade 3 or 4), renal dysfunction (especially proteinuria) and/or hypertensive encephalopathy (see above). Left ventricular failure may occur and, if this is untreated, death occurs within months.

Investigations

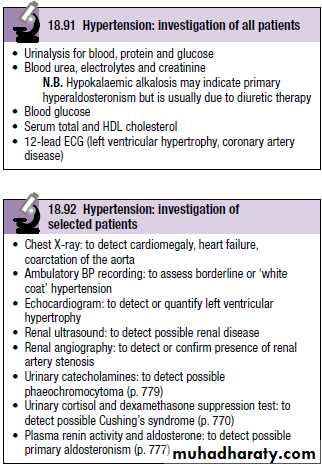

All hypertensive patients should undergo a limited number of investigations (Box 18.91). Additional investigations are appropriate in selected patients (Box 18.92).

Treatment

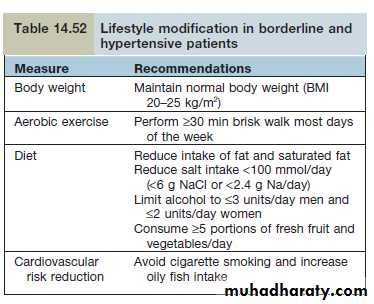

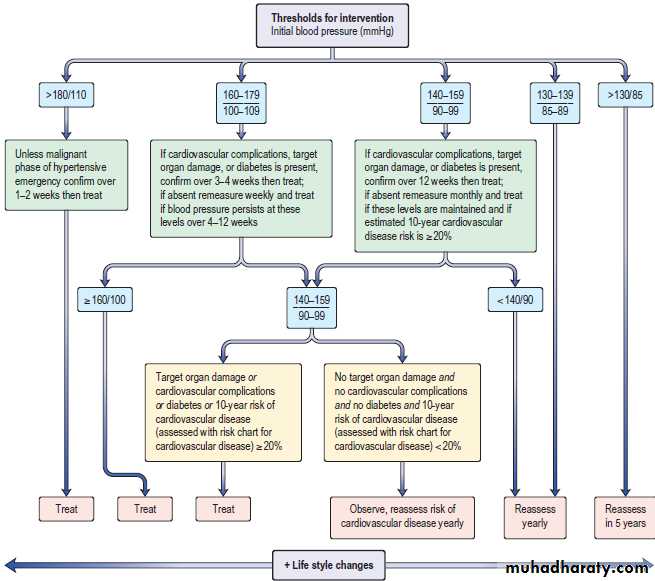

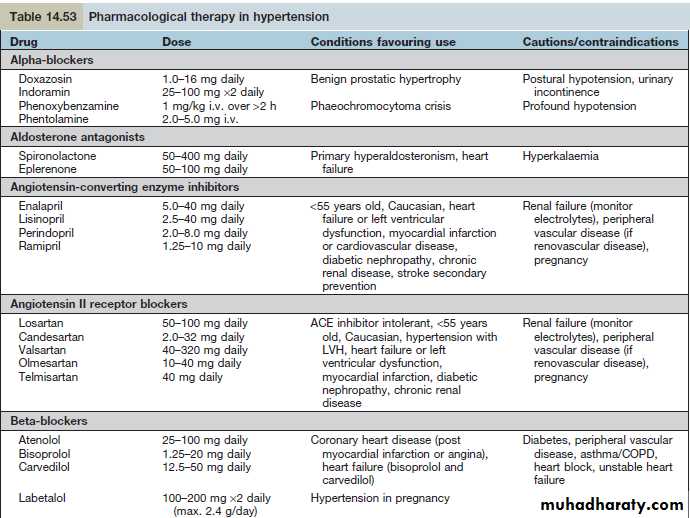

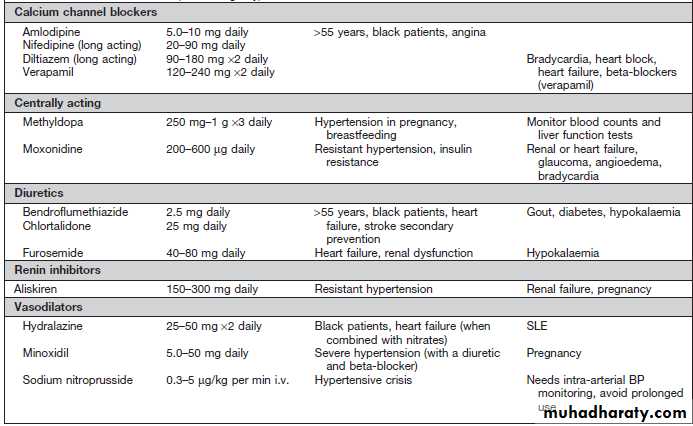

Unless the patient has severe or malignant hypertension, there should be a period of assessment with repeated blood pressure measurements, combined with advice and non-pharmacological measures prior to the initiation of drug therapy (Table 14.52(The British Hypertension Society provides guidance on when treatment should be commenced (Fig. 14.120(

Target blood pressure

For most patients, a target of ~140 mmHg systolic blood pressure and ≈85 mmHg diastolic blood pressure is recommended. For patients with diabetes, renal impairment or established cardiovascular disease a lower target of ≈130/80 mmHg is recommended.

When using ambulatory blood pressure readings, mean daytime pressures are preferred and this value would be expected to be approximately 10/5 mmHg lower than the clinic blood pressure equivalent for both thresholds and targets. Similar adjustments are recommended for averages of home blood pressure readings.

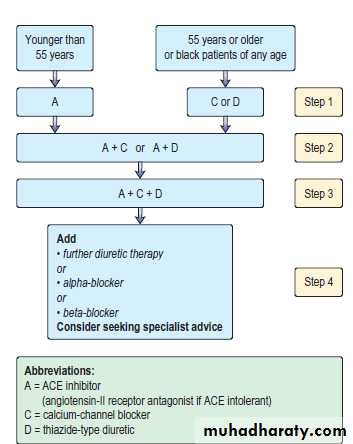

The main determinant of outcome following treatment is the level of blood pressure reduction that is achieved rather than the specific drug used to lower blood pressure.

Most hypertensive patients will require a combination of antihypertensive drugs to achieve the recommended targets.

In most hypertensive patients therapy with statins and aspirin is added to reduce the overall cardiovascular risk burden. Glycaemic control should be optimized in diabetics (HbA1c <7%).