Cardiology Lectures Dr. Ahmed Moyed Hussein

Atrial fibrillation:Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia. The prevalence rises with age. AF is a complex arrhythmia characterized by both abnormal automatic firing and the presence of multiple interacting re-entry circuits looping around the atria.

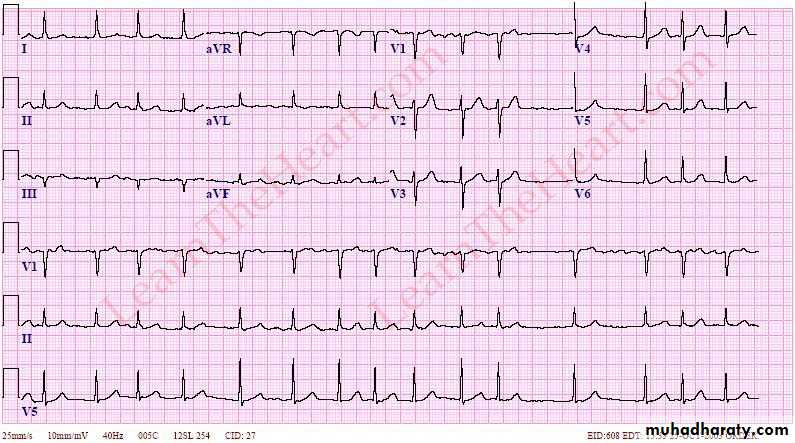

During episodes of AF, the atria beat rapidly but in an uncoordinated and ineffective manner. The ventricles are activated irregularly at a rate determined by conduction through the AV node. This produces the characteristic ‘irregularly irregular’ pulse. The ECG shows normal but irregular QRS complexes; there are no P waves but the baseline may show irregular fibrillation waves.

Fig: AF

AF can be classified as paroxysmal (intermittent episodes which self-terminate within 7 days), persistent (prolonged episodes that lasting more than 7 days up to 1 year and can be terminated by electrical or chemical cardioversion) or permanent (if it last for more than 1 year). Unfortunately for many patients, paroxysmal AF will become permanent as the underlying disease process that predisposes to AF progresses.It also can be classified into Valvular AF ( occur in patients with rheumatic mitral stenosis, bioprosthetic or mechanical valve or mitral valve repair) and Nonvalvular AF.

Causes of AF:

Coronary artery disease (including acute MI)Valvular heart disease, especially rheumatic mitral valve disease

Hypertension

Sinoatrial disease

Hyperthyroidism

Alcohol

Cardiomyopathy

Congenital heart disease

Chest infection

Pulmonary embolism

Pericardial disease

Idiopathic (lone atrial fibrillation)

AF can cause palpitation, breathlessness and fatigue. In patients with poor ventricular function or valve disease, it may precipitate or aggravate cardiac failure because of loss of atrial function and heart rate control.

The most disabling consequence of AF is its association with stroke and systemic embolism. Careful assessment, risk stratification and therapy can markedly improve prognosis.

Management:

Assessment of patients with newly diagnosed AF includes a full history, physical examination, 12-lead ECG, echocardiogram and thyroid function tests.The main objectives are:

Restoration of sinus rhythm (when possible).

Prevention of recurrent AF.

Optimization of the heart rate during periods of AF.

Reduction of the risk of thromboembolism.

Treatment of underlying cardiac disease.

Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation:

Occasional attacks that are well tolerated do not necessarily require treatment. Beta-blockers are normally used as first-line therapy if symptoms are troublesome. Class Ic drugs such as propafenone or flecainide are also effective at preventing episodes but should not be given to patients with coronary artery disease or left ventricular dysfunction. Class III drugs can also be used; like amiodarone and Dronedarone. In patients with AF in whom anti-arrhythmic drug therapy is ineffective or causes side-effects, catheter ablation can be considered.Persistent and permanent atrial fibrillation:

There are two options for treating persistent AF:• rhythm control: attempting to restore and maintain sinus rhythm

• rate control: accepting that AF will be permanent and using treatments to control the ventricular rate and to prevent embolic complications.

Rhythm control: An attempts to restore and maintain sinus rhythm are most successful if AF has been present for less than 3 months, the patient is young and there is no important structural heart disease.

Immediate cardioversion, after administration of intravenous heparin, is appropriate if AF has been present for under 48 hours. In stable patients with no history of structural heart disease, intravenous flecainide (2 mg/kg over 30 mins, maximum dose 150 mg) can be used for pharmacological cardioversion.

In patients with structural or ischemic heart disease, intravenous amiodarone can be given via a central venous catheter. Electrical cardioversion, using a DC shock, is an alternative and is often effective when drugs fail. Anticoagulation should be maintained for at least 3 months following successful cardioversion.

Rate control: If sinus rhythm cannot be restored, treatment should be directed at maintaining an appropriate heart rate. Digoxin, β-blockers and rate-limiting calcium antagonists, such as verapamil or diltiazem can be used.

Prevention of thromboembolism:

Loss of atrial contraction and left atrial dilatation cause stasis of blood in the left atrium and may lead to thrombus formation in the left atrial appendage. This predisposes patients to stroke and other forms of systemic embolism.Warfarin is thus indicated for patients with AF who have specific risk factors for stroke. Risk stratification is based on clinical factors using the CHA2DS2-VASC scoring system.

Until recently, warfarin was the treatment of choice, mandating regular blood testing, with a target INR of 2.0–3.0. The direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran, is the first novel oral anticoagulant drug shown to be as effective and safe as warfarin at stroke prevention in non valvular AF.

Atrial flutter:

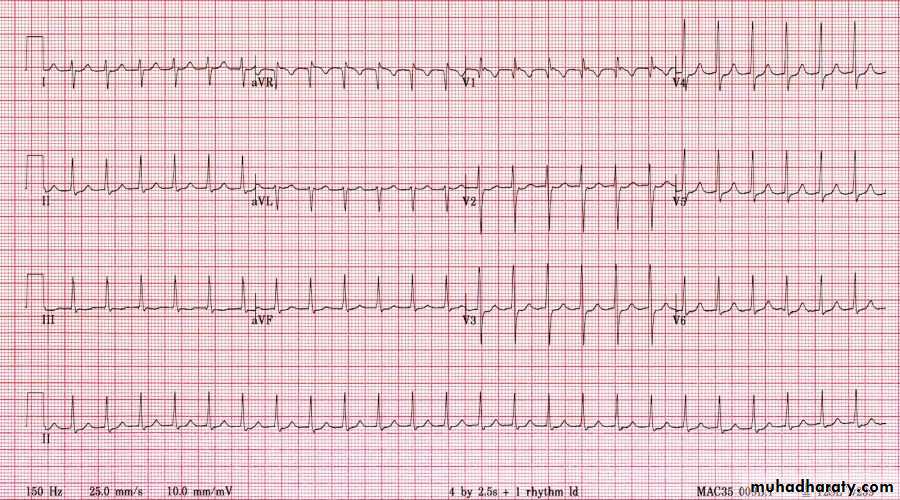

Atrial flutter is characterized by a large (macro) re-entry circuit, usually within the right atrium encircling the tricuspid annulus. The atrial rate is approximately 300/min, and is usually associated with 2 : 1, 3 : 1 or 4 : 1 AV block (with corresponding heart rates of 150, 100 or 75/min).The ECG shows sawtoothed flutter waves.

Fig: Atrial flutter with 4:1 block( flutter waves marked by arrows)

Management:Digoxin, β-blockers or verapamil can control the ventricular rate. However, in many cases, it may be preferable to try to restore sinus rhythm by direct current (DC) cardioversion or by using intravenous amiodarone. Catheter ablation offers a 90% chance of complete cure and is the treatment of choice for patients with persistent symptoms.

Supraventricular tachycardias:

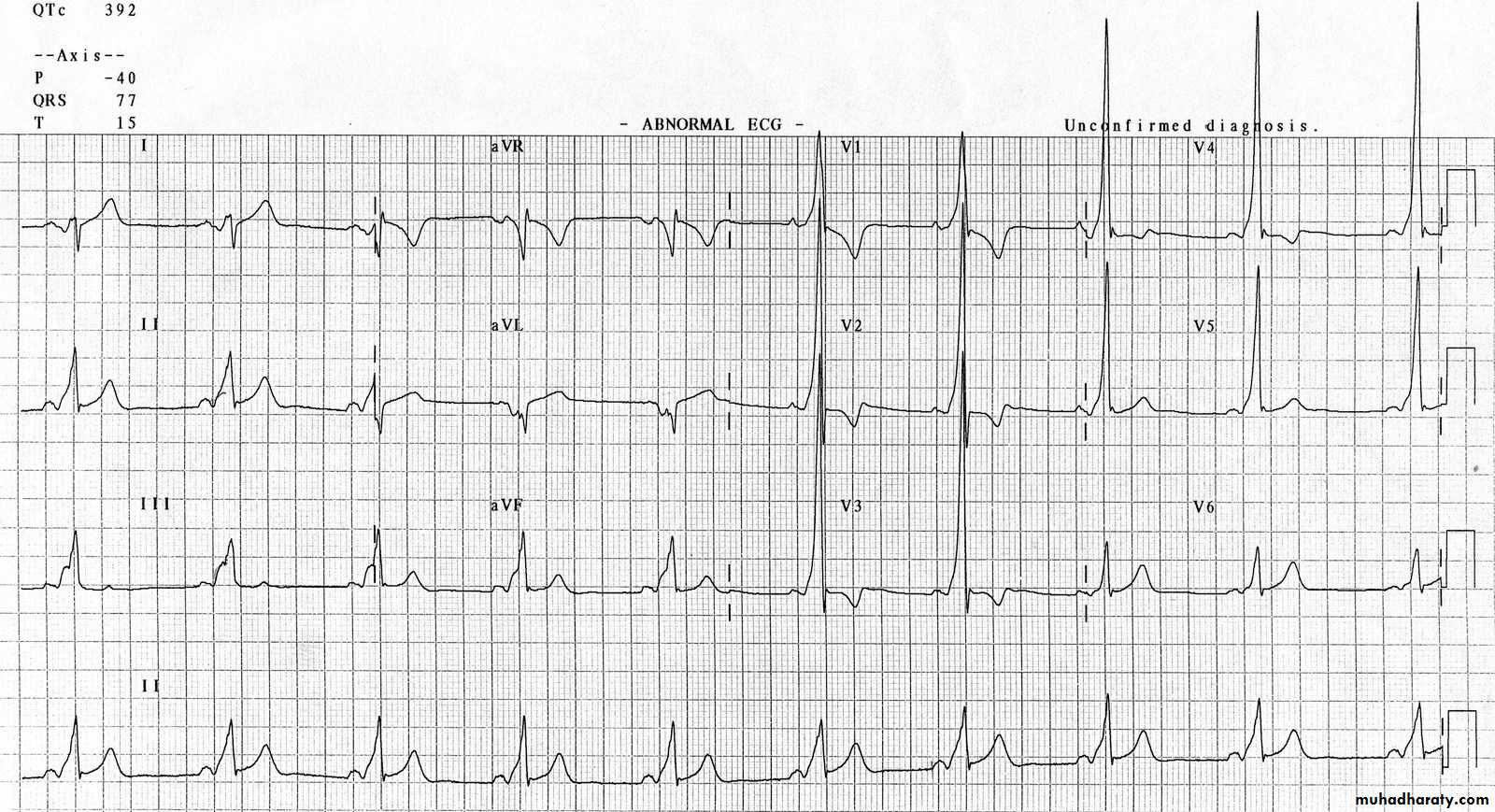

The term ‘supraventricular tachycardia’ (SVT) is commonly used to describe regular tachycardias that have a similar appearance on ECG. These are usually associated with a narrow QRS complex and are characterized by a re-entry circuit or automatic focus involving the atria.Atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT):

is due to re-entry in a circuit involving the AV node, This produces a regular tachycardia with a rate of 120–240/min. It tends to occur in the absence of structural heart disease and episodes may last from a few seconds to many hours. The patient is usually aware of a rapid, very forceful, regular heart beat and may experience chest discomfort, lightheadedness or breathlessness. Polyuria, mainly due to the release of atrial natriuretic peptide, is sometimes a feature. The ECG usually shows a tachycardia with normal QRS complexes.

Fig: SVT

Management:Episode may be terminated by carotid sinus pressure or by the Valsalva manoeuvre (vagal stimulation). Adenosine (3–12 mg rapidly IV) or verapamil (5 mg IV over 1 min) will restore sinus rhythm in most cases. Intravenous β-blocker or flecainide can also be used. In rare cases, when there is severe haemodynamic compromise, the tachycardia should be terminated by DC cardioversion.

In patients with recurrent SVT, catheter ablation is the most effective therapy and will permanently prevent SVT in more than 90% of cases. Alternatively, prophylaxis with oral β-blocker, verapamil or flecainide may be used.

Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome(WPW) and atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia:

Here, an abnormal band of conducting tissue connects the atria and ventricles. This ‘accessory pathway’ comprises rapidly conducting fibers which resemble Purkinje tissue. Premature ventricular activation via the pathway shortens the PR interval and produces a ‘slurred’ initial deflection of the QRS complex, called a delta wave. As the AV node and accessory pathway have different conduction speeds and refractory periods, a re-entry circuit can develop, causing tachycardia, The ECG during this tachycardia is almost indistinguishable from that of AVNRT.Carotid sinus pressure or intravenous adenosine can terminate the tachycardia. Catheter ablation is first-line treatment in symptomatic patients and is nearly always curative. Alternatively, prophylactic anti-arrhythmic drugs, such as flecainide or propafenone, can be used to slow conduction in the accessory pathway.