13

Journal of Education and Ethics in Dentistry

January-June 2012 • Vol. 2 • Issue 1

Medical and dental emergencies and complications in

dental practice and its management

Access this article online

Quick Response Code:

Website:

www.jeed.in

DOI:

10.4103/0974-7761.115144

Introduction

An emergency is a medical condition that demands

immediate attention and successful management. These are

the life‑threatening situations of which every practitioner

must be aware of so that needless morbidity can be avoided.

A survey of 4000 dental surgeons conducted by Fast and

others revealed an incidence of 7.5% emergencies per dental

surgeon over a 10‑year period.

[1]

Emergencies can be prevented to a certain extent by a detailed

medical history, physical examination, and patient monitoring.

Preparation for an emergency and sound knowledge about the

management of all emergencies in general is of prime concern

to dental specialists.

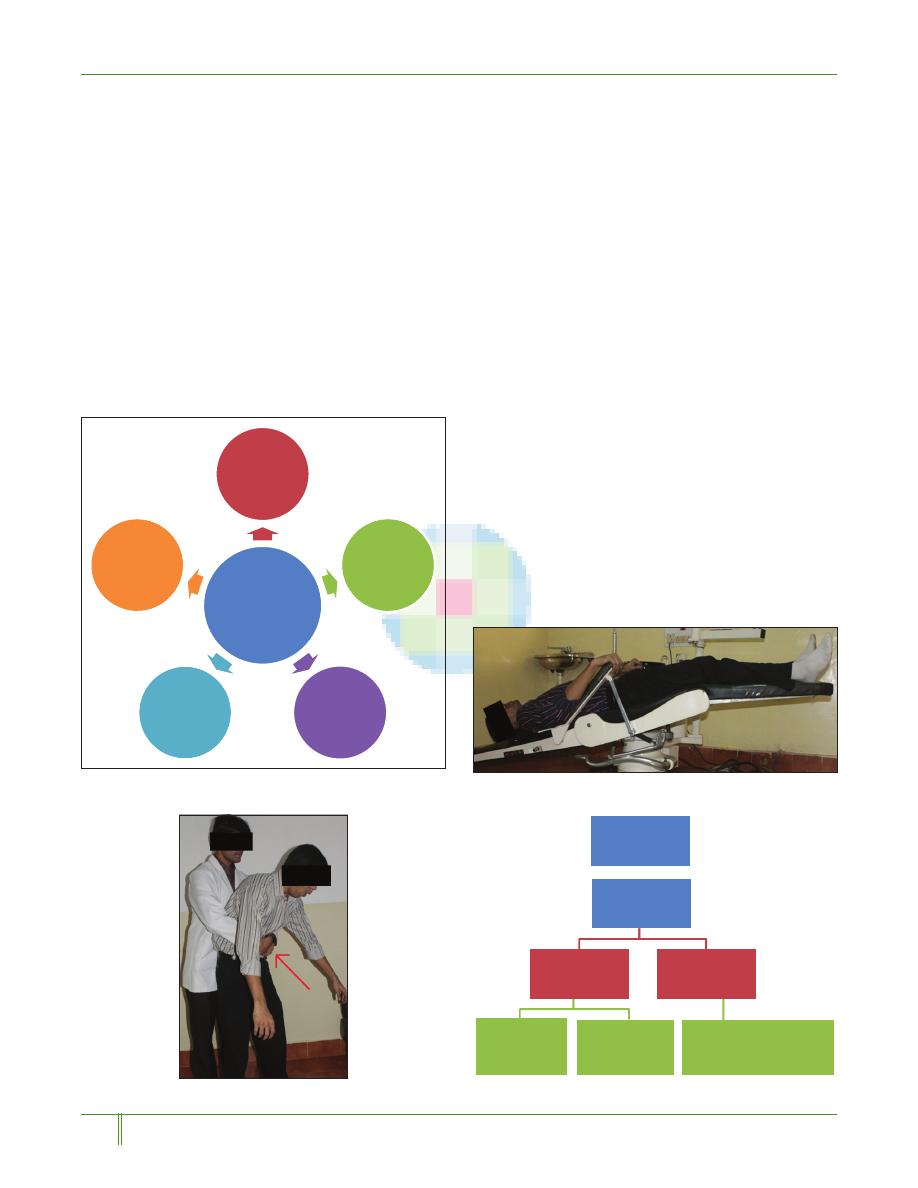

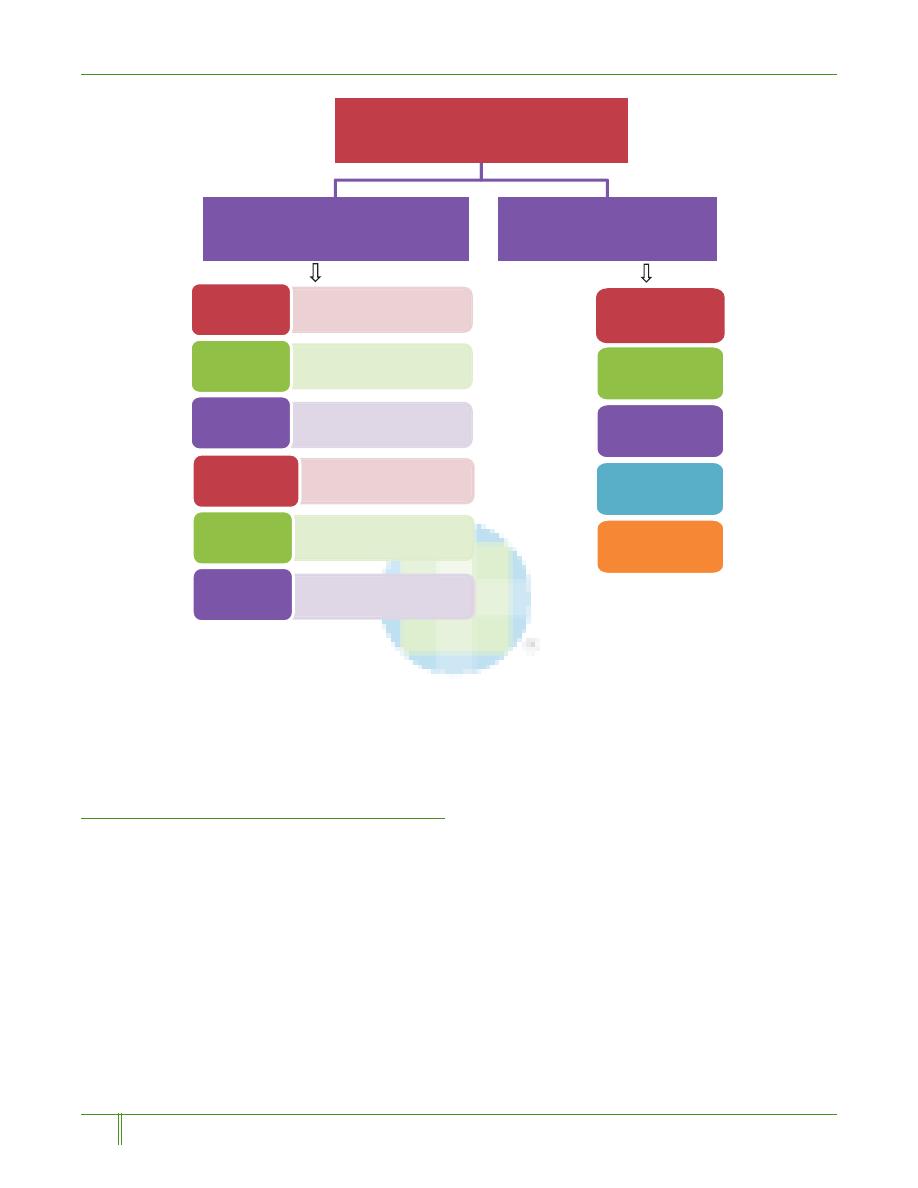

Basic principles of management of medical

emergencies

The golden rule in managing any emergency is rendering

basic life support (BLS) measures and cardiopulmonary

resuscitation (CPR). This is done by following the basic

principles: Position (P), Airway (A), Breathing (B),

Circulation (C), and Definitive therapy (D)

[2]

[Figure 1].

The primary positions to manage an emergency are

supine position, Trendelenburg position, and semi‑erect

position.

[3]

Maintaining a patent and functioning airway

is the first priority in managing an emergency. This is

achieved usually by the head tilt‑chin lift manoeuvre.

[4]

If

clear airway is still not achieved, then invasive procedures

like direct laryngoscopy and cricothyrotomy can be

followed. The next priority is to check for the presence

of adequate breathing which is assessed by the look‑feel

and listen technique.

[4]

If spontaneous breathing is not

evident then rescue breathing should be accomplished

immediately either by the mouth‑to‑mouth technique or

the bag‑valve‑mask technique. After establishing a patent

airway and breathing, circulation is assessed. The most rapid

and reliable method is by palpating the carotid pulse at the

region of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. If pulse is absent,

then CPR is initiated immediately. Once airway, breathing,

and circulation is maintained, definitive treatment is begun

if the emergency is acute and cause is clear to the dental

specialist. Definitive therapy involves administration of

drug when indicated and contacting for emergency care.

The medical and dental emergencies that are commonly

encountered in dental practice involve syncope, airway

obstruction, anaphylaxis, local anesthetic toxicity, asthmatic

attack, chest pain, hemorrhage, and seizure. Myocardial

infarction and cardiac arrest are extremely rare. Analysis of

history and patient counseling and motivation also play a role

in minimizing the emergencies.

Department of Prosthodontics and Crown and Bridge, A.B. Shetty Memorial Institute of Dental

Sciences (A constituent College of Nitte University), Deralakatte, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

ABSTRACT

Any dental professional can encounter an emergency during the course of their treatment.

Every Dental specialist should have the knowledge to identify and manage a potentially

life‑threatening situation. Prompt recognition and efficient management of an emergency

by the specialist results in a satisfactory outcome. Though rare, emergencies do occur in a

dental clinic. The ultimate goal in the management of all emergencies is the preservation of

life. The prime requisite in managing an emergency is maintenance of proper Position (P),

Airway (A), Breathing (B), Circulation (C), and Definitive treatment (D). The purpose of this

article is to provide a vision to the commonly occurring medical and dental emergencies and

complications in dental practice and their management. Data for the study was collected from

PubMed data base search.

Key words:

Anaphylaxis, asthmatic attack, complications, local anesthetic toxicity,

medical emergencies, syncope

Krishna D Prasad,

Chethan Hegde,

Harshitha Alva, Manoj Shetty

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Harshitha Alva,

Department of Prosthodontics

and Crown and Bridge,

A.B Shetty Memorial Institute

of Dental Sciences, Mangalore,

Karnataka - 575 018, India.

E-mail: drharshitha@gmail.com

Review

Article

[Downloaded free from http://www.jeed.in on Sunday, June 18, 2017, IP: 159.255.164.73]

Journal of Education and Ethics in Dentistry

January-June 2012 • Vol. 2 • Issue 1

14

Prasad, et al.: Emergencies, complications and their management

Syncope

Syncope is caused due to inadequate cerebral perfusion.

Causes of sudden loss of consciousness and collapse include

hypotension, adrenal crisis, anaphylaxis, cardiac arrest,

diabetic collapse, hypoglycemia, epileptic seizure, fainting,

or stroke.

[5]

The early manifestations include nausea, warmth,

perspiration, baseline blood pressure, and tachycardia. Late

manifestations include hypotension, bradycardia, pupillary

dilation, peripheral coldness, and visual disturbance. Most

of the syncopal attacks can be prevented by ensuring that

the patient has had their meal before treatment in case of

systemic diseases like diabetes and also making the patient lie

in the supine position before administering local anesthetics.

[5]

Management: The patient should be in the supine position

[Figure 2]. Recovery is almost instantaneous if the patient has

simply fainted. Then maintain airway, check pulse (if absent,

indicates cardiac arrest), and start CPR immediately. If pulse is

palpable and the patient has not completely lost consciousness,

four sugar lumps may be given orally or intravenous 20 ml of

20‑50% sterile glucose. A hypoglycemic patient will improve

with this regimen. But if there is still no improvement medical

assistance should be summoned. Meantime, hydrocortisone

sodium succinate 200 mg IV should be given.

[5]

Airway obstruction

Airway obstruction is usually caused due to accidental slippage,

aspiration of foreign objects, or laryngeal spasm. Patient

manifests with inability to speak, grasps the throat (universal

sign), coughs, inability to exchange air (in spite of respiratory

movements), cyanosis, and loss of consciousness. These might

eventually lead to cardiac arrest finally.

Management: Main priority is to clear the airway, but the

method differs depending upon whether the patient is

conscious or unconscious. If the patient is conscious, then

he/she must be made to sit straight, support chest with one

hand, and deliver five sharp back blows between the shoulder

blades with the heel of the other hand. But if the patient is

choking, an attempt is made to expel the object with upward

thrusts using Heimlich thrust [Figure 3]. It acts as artificial

cough that produces a rapid increase in intra‑thoracic pressure

thus helping to expel the foreign body [Figure 4].

In an unconscious patient: The patient is got to a supine

position and deliver inward and upward thrust five times.

&LU

'HILQLWLYH

7KHUDS\

3

P

FXODWLRQ

3ULQFLSOHVRI

HPHUJHQF\

PDQDJHPHQW

3RVLWLRQ

%UHDWKLQJ

$LUZD\

Figure 1: Principles of emergency management

Figure 2: Syncope management : Trendelenburg Position

Figure 3: Heimlich Thrust

$VVHVVVHYHULW\

6HYHUHDLUZD\

REVWUXFWLRQ

,QHIIHFWLYHFRXJK

8QFRQVFLRXV

6WDUW&35

&RQVFLRXV

EDFNEORZV

DEGRPLQDOWKUXVWV

0LOGDLUZD\

2EVWUXFWLRQ

(IIHFWLYHFRXJK

(QFRXUDJH&RXJK

&RQWLQXHWRFKHFNIRU

GHWHULRUDWLRQWRLQHIIHFWLYH

FRXJKRUUHOLHIIURPREVWUXFWLRQ

$LUZD\REVWUXFWLRQ

Figure 4: Airway obstruction management

[Downloaded free from http://www.jeed.in on Sunday, June 18, 2017, IP: 159.255.164.73]

15

Journal of Education and Ethics in Dentistry

January-June 2012 • Vol. 2 • Issue 1

Prasad, et al.: Emergencies, complications and their management

This thrust is followed by turning patient to one side to clear

oral cavity. Attempt to re‑ventilate, commence CPR and

administer oxygen

.

If the foreign object is still not dislodged

and patient’s condition deteriorates, then a surgical airway is

created by Laryngoscopy or cricothyrotomy.

[5]

A 10‑year institutional review on aspiration and ingestion in

dental practice concluded that dental procedures involving

single‑tooth cast or prefabricated restorations involving

cementation have a higher likelihood of aspiration. This can

be prevented by measures such as use of rubber dams or

gauze, throat screens, or floss ligatures.

[6]

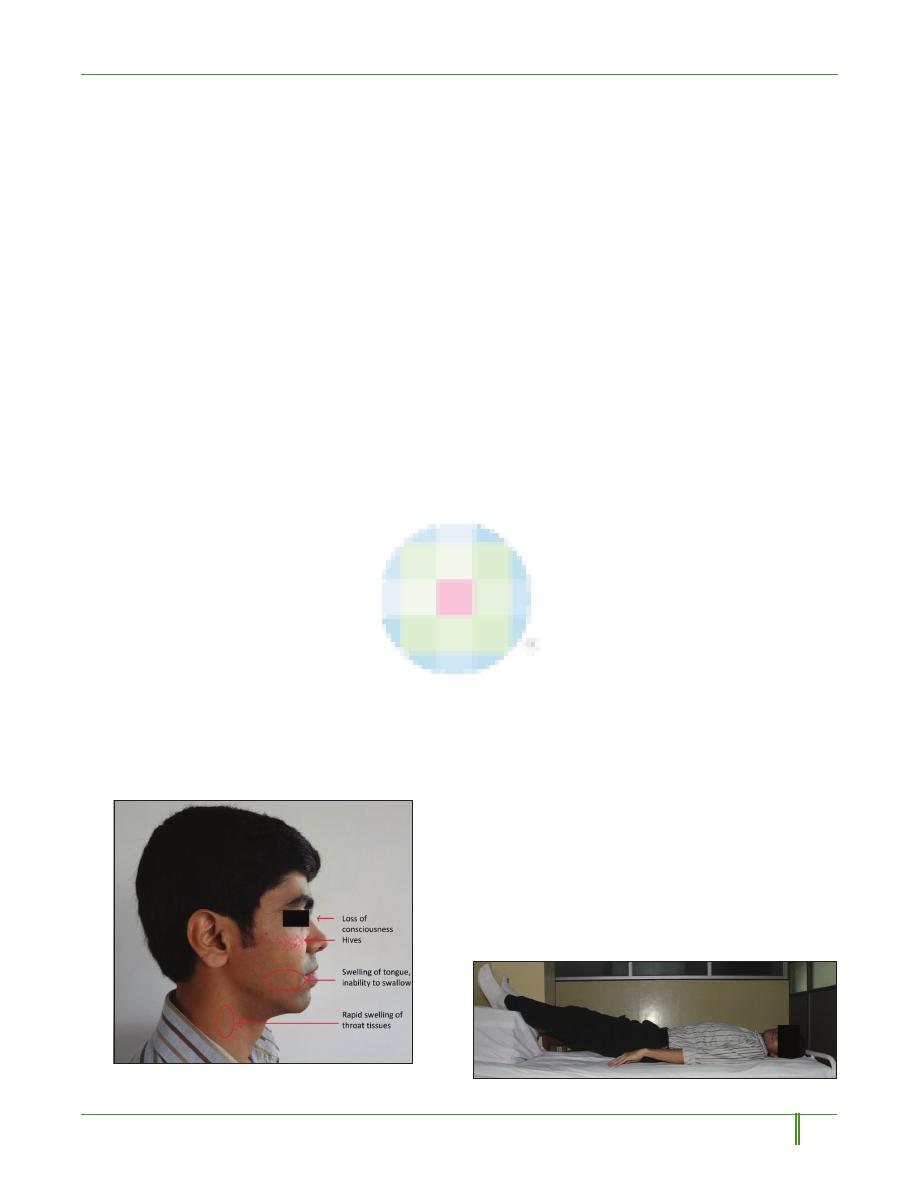

Anaphylaxis

It is a hypersensitive state that results from exposure to

an allergen. The most common allergen in a dental setup

is latex.

[2]

Manifestations vary from a mild form where the

patient presents with erythematous rash, cyanosis, nausea,

vomiting, tachycardia, utricaria, or angiodema to a severe

form which leads to airway obstruction or inadequate blood

pressure and blood flow to the brain which is a life‑threatening

situation [Figure 5]. Management involves lying the patient

in the supine position with legs raised [Figure 6], administer

oxygen, and the drug of choice being 0.5 ml of 1:1000

adrenaline IM or SC.

[5]

Local anesthetic toxicity

Local anesthetics are the most commonly used drugs in

dentistry. Toxicity is usually either due to the local anesthetic

itself or the vasoconstrictor which can be due to rapid infusion

or failure to aspirate before injection. Generally, the reactions

are self limiting. Toxicity presents with talkativeness, slurred

speech, anxiety, confusion, drowsiness, or even seizure and

cardiac arrhythmias in extreme cases.

Management: Sessate the administration of injection and

monitor vital signs. Administer oxygen and in adverse cases

administration of diazepam 5 mg slowly is advised.

[5]

Asthmatic attack

Anxiety, infection, exposure to an allergen or drugs can

precipitate an asthmic attack. The goal of management during

an acute asthmatic episode on a dental chair should be to

relieve the bronchospasm associated with the attack. Patient

presents with thickness or heaviness in the chest, difficulty

in breathing, spasmodic and unproductive cough, expiratory

wheeze, and anxious behavior. Hence, the patient should

primarily be relieved of irritants and all articles should be

removed from oral cavity.

[5]

Drug of choice is 2 puffs of albuterol. If no improvement is

seen in 15 seconds then administer 1:1000 adrenaline 0.5 ml

SC/IM and if still no response is observed in 2‑3 min then

salbutamol slow IV injection is advised.

[5]

Chest pain

Factors that precipitate chest pain include angina, acute

myocardial infarction, gastrointestinal reflux disease, anxiety,

costochondritis and paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.

[2]

Patients generally present with tightness, fullness, constriction,

or heavy weight on the chest. Angina pectoris and acute

myocardial infarction (AMI) are the two commonly occurring

cardiac problems in a conscious patient. Patient’s history is of

prime concern here. If this is the first time patient has ever

experienced a chest pain, then dental specialist should treat

him or her as if it were an acute myocardial infarction and

have emergency medical service transfer immediately. If not

then it is an angina pectoris situation.

Quality of pain can also indicate whether the patient is having

an angina or acute myocardial infarction. In angina pectoris

pain is significant but not severe whereas an acute myocardial

infarction pain generally radiates to left side of the body‑left

shoulder, left mandible, left arm.

[2]

Management: For angina pectoris, drug of choice is a nitrate,

commonly nitroglycerine, sublingual tablet, translingual or

transmucosal spray. Management of a patient with suspected

acute myocardial infarction involves administration of

morphine, oxygen, nitroglycerine, and aspirin (MONA)

in addition to emergency medical service. If morphine is

unavailable, the specialist can also substitute nitrous oxide/

oxygen in a 50:50 concentration.

[2]

Haemorrhage

Haemorrhagic disorders, though uncommon, should always

Figure 5: Schematic representation of the areas to be observed

for signs and symptoms of Anaphylaxis

Figure 6: Management of anaphylaxis

[Downloaded free from http://www.jeed.in on Sunday, June 18, 2017, IP: 159.255.164.73]

Journal of Education and Ethics in Dentistry

January-June 2012 • Vol. 2 • Issue 1

16

Prasad, et al.: Emergencies, complications and their management

be considered, as dental specialists deal with blood routinely

and there are instances when significant bleeding could lead

into an emergency. Emergency management begins by gently

cleaning the mouth and locating the source of bleeding and

the application of cold compress, pressure packs, or styptics.

Suture the area under L.A when necessary. Tranexamic

acid –500 mg in 5 ml by slow IV injection is the drug of

choice.

[2,5]

Seizures

Patients who convulse in dental office generally have a seizure

history and are often characterized as having epilepsy.

Management: If the patients experiencing seizure is

unconscious, they should primarily be placed in the supine

position and the head tilt‑chin lift manoeuvre is performed.

Dental specialist should remove all instruments from patient’s

mouth and protect the patient. Clear airway, loosen clothing

and help patient breath adequately.

If seizure continues for long, then the condition is known

as status epilepticus. This is a life‑threatening emergency

and is best managed with I.V. diazepam 5 mg IV/IM or

by maintaining BLS till patient is shifted to emergency

medical care.

Dental Complications

More than dental emergencies which require an immediate

attention and management, the occurrence of “complications”

are of higher incidence in dental practice. The complications

may be immediate or delayed and are related to patient’s

tolerance level, materials used and treatment procedures.

In an interdisciplinary dental practice the most common

complication is aspiration. Aspiration may be of the denture

as a whole or a fractured part, a minimal extension acrylic

removable prosthesis, crowns during removal, instrument

slippage especially broaches reamers or files. Aspiration causes

airway obstruction which is manifested as the universal sign

“choking.” Removal of broken instruments is performed using

ultrasonics, operating microscopes or microtube delivery

methods.

[7]

Allergy is another complication commonly encountered by a

dental specialist.

Allergy can be to latex, mercury, rubber dam, and impression

material. Manifestations of allergy include pruritis, erythema,

utricaria, and angioneurotic edema. Minimizing latex exposure

is most effective when treating latex‑sensitive patients. Latex

alternatives (vinyl, nitrite, or silicone) and powder‑free

gloves should be used to prevent sensitization. Fixers like

formacresol and devitalizers to be used carefully to prevent

chemical burns. Allergy to alloys like nickel–chromium and

chromium–cobalt has also been encountered.

Complications involving local anaesthetics are hypersensitivity,

toxic reactions, and allergy.

[8]

The most severe form of

hypersensitivity is anaphylaxis which is a life‑threatening

generalized or systemic reaction.

[9]

Anaphylaxis can be either

allergic or non‑allergic. Allergic hypersensitivity can be

immediate due to IgE or delayed which is T‑cell mediated.

[10]

Management

involves

administering

prophylactic

antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine or corticosteroids

such as prednisone before dental treatment to those at known

risk

[8,9]

and the drug of choice is 0.3‑0.5 ml intra‑muscular or

subcutaneous doses of 1:1000 epinephrine.

[10]

Allergic reactions can also occur to acrylic resins, which can

be minimized by following proper monomer polymer ratio,

correct curing cycle so as to minimize the residual monomer

content in the prosthesis.

Interference of a cardiac pacemaker by an electronic dental

device was studied by Roedig et al. The pacing activity of

both pacemakers and the dual‑chamber ICD was inhibited by

a battery‑operated composite curing light at between 2 and

10 cm from the leads. The use of an ultrasonic scaler interfered

with the pacing activity of the dual‑chamber pacemaker

between 17 and 23 cm from the leads, the single‑chamber

pacemaker at 15 cm from the leads and both ICDs at

7 cm from the leads. Operation of the electric toothbrush,

electrosurgical unit, electric pulp tester, high‑ and low‑speed

handpiece, and an amalgamator did not alter pacing function.

The article concluded that the use of the ultrasonic scaler,

ultrasonic cleaning system, and battery‑operated composite

curing light may produce deleterious effects in patients who

have pacemakers or ICDs.

[11]

An immediate complication usually manifested during an

endodontic therapy is hypochlorite accident wherein sodium

hypochlorite is expressed beyond the apex and patients

manifests with severe pain, swelling or profuse bleeding.

Immediate management involves administration of a regional

block and then wait till maximum drainage occurs.

Antibiotics: Penicillin 500 mg five times a day for 7 days is

prescribed.

Complications and emergencies encountered during

implant therapy

Complications can be either related to the surgery or implant

placement. The intra‑operative complications related to

surgery are haemorrhages, neurosensory alteration, damage to

the adjacent teeth, and mandibular fractures.

[12]

Haemorrhages in the mandible most frequently occur in the

intra‑foraminal region by damage to the descending palatine

artery or the posterior palatine artery. Respiratory obstruction

has also been reported due to perforation of the arteries

supplying the mandible.

[13]

This is believed to be due to the

[Downloaded free from http://www.jeed.in on Sunday, June 18, 2017, IP: 159.255.164.73]

17

Journal of Education and Ethics in Dentistry

January-June 2012 • Vol. 2 • Issue 1

Prasad, et al.: Emergencies, complications and their management

massive internal haemorrhage caused due to the vascular injury

in the floor of the mouth which creates a swelling, producing

protrusion, and displacement of the tongue, thus obstructing

the airway.

[14,15]

Haemorrhages can be managed by strong

finger pressure at the point of bleeding but if compressions

don’t obtund bleeding then at times anastomoses necessitates

ligation.

[12]

Another complication related to surgery is

neurosensory disturbance which manifests as anaesthesia,

paresthesia, hypoesthesia, or dysesthesia. If the patient suffers

from paresthesia but implant is placed correctly with no

damage to the nerve, then retrieval of implant is not advised;

instead wait for recovery. However, if the nerve is being

compressed, it is always advisable to remove the implant to

avoid permanent neural damage.

[16]

Damage to the adjacent

teeth occurs due to lack of parallelism of the implant with the

adjacent teeth. Hence, it is always mandatory that a distance

of 1.5 mm be maintained from the adjacent teeth.

In case of damage, treatment of the affected teeth include

endodontic therapy, periapical surgery, apicectomy, or

extraction.

[17]

Mandibular fractures are rare and occur when

implants are placed in atrophic mandible.

Complication associated with implant placement most

importantly involves loss of primary stability which can be

attributed to overworking of the implant bed, poor bone

quality or use of short implants.

[12]

An increase in temperature

due to excessive speed of the drill produces necrosis, fibrosis,

osteolytic degeneration, and increased osteoclastic activity.

[18]

Loss of primary stability can be managed by using a wider and

longer self‑tapping implant.

[19]

Another possible complication

is manifestation of dehiscence or fenestration, managing

which involves filling the bone defect with bone grafts and

resorbable or non‑resorbable membranes.

[20]

During implant

placement in the maxilla in areas close to sinus or during sinus

lift procedures, complications involving rupture of Schneider

membrane can occur. Depending on the width of the tear, a

resorbable membrane may be used which serves to contain

the bone graft material, or if the tear is very wide, then surgery

is postponed.

Another complication is the displacement of the implants into

the maxillary sinus during the surgery or in the postoperative

period. In some cases, it can lead to sinusitis or even remain

asymptomatic.

These emergencies and complications can be minimized

by appropriate pre‑surgical planning, use of accurate

surgical techniques, postsurgical follow‑up, respecting

the osseointegration period, appropriate design of the

superstructure, biomechanics, and advocating meticulous

hygiene during the maintenance phase.

Recent advances in the management of emergencies

The most recent advancement is the revised CPR guideline

by the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2010. Instead

of ABC, now compressions come first only then do airway

and breathing.

Initially, it was believed that the chest compressions should

be at least 1‑1.5 inches deep but now at least 2 inch deep

compressions are recommended and also instead of pushing

on the chest at about 100 compressions per minute, AHA

now recommends to push at least 100 compressions per

minute.

[21]

Discussion

As always believed, prevention is the best medicine. Hence,

being prepared for an emergency and believing that emergency

is a real possibility in a dental clinic is of utmost importance.

Preparation for emergencies involves personal, staff, and office

preparation wherein personal and staff preparation include

an in depth knowledge of signs, symptoms, and management

of emergencies, basic life support (BLS) measures, and

cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Office preparation

involves maintaining emergency equipment, emergency

drugs, and backup medical assistance.

Whenever an emergency has been recognized, most

important is to follow DRS‑ABC Emergency equipments

that are indispensible in a dental set‑up involve a dental chair

which can be readily adjusted to Trendelenburg position, high

volume suction to clear oral secretions, disposable needle and

syringe, oxygen cylinder with face mask and AMBU bag, and

maintenance of IV access. Dental specialist should always

remember that administration of drugs is not necessary for

management of an emergencies and primary management

always involves BLS measures.

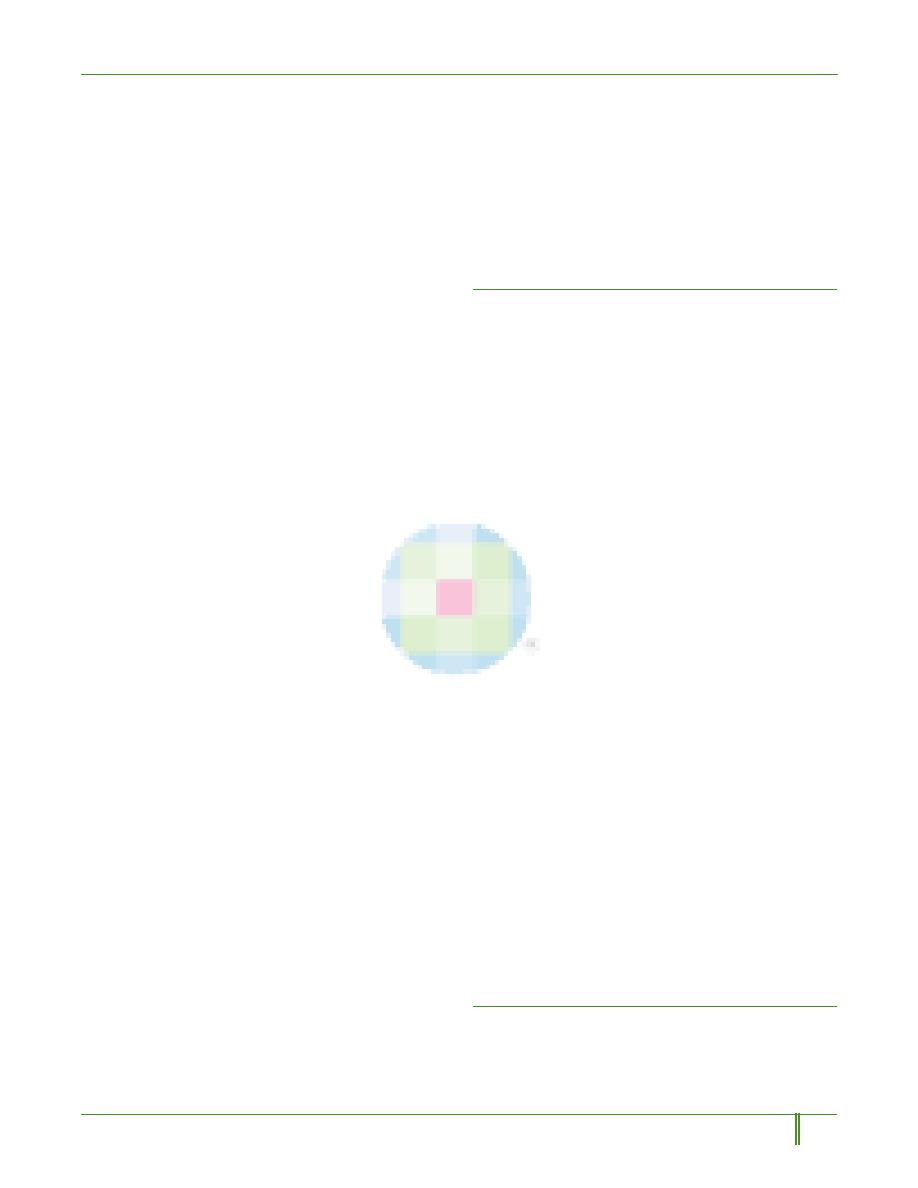

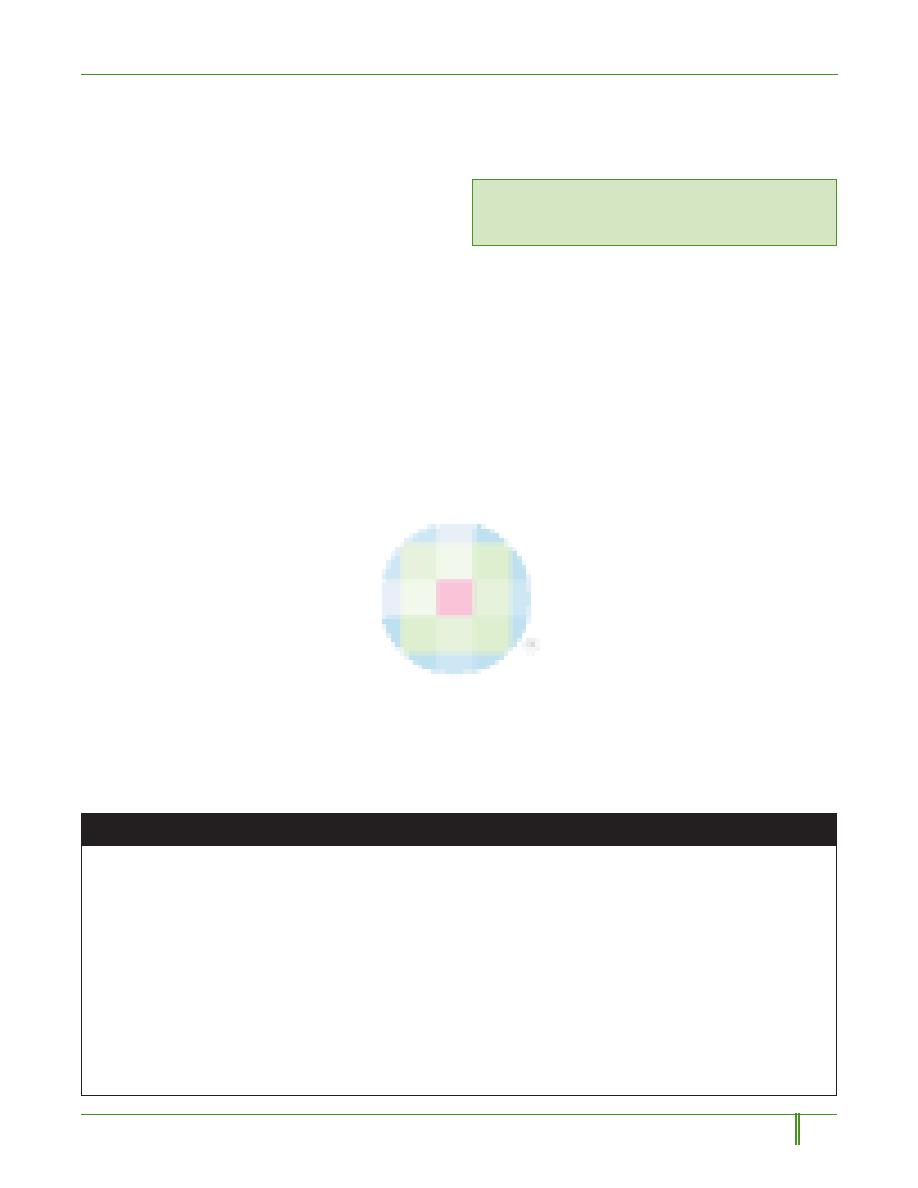

Emergency kit should comprise of airway accessories and

pharmacological agents

[1,22]

[Figure 7].

In case of referral dental practice, any positive observations by

the specialist may be shared while referring to another specialist

for the necessary precautions using a medical alert note. The

patient should be psychologically motivated and prepared to

face the emergency situation if arises before commencement

of treatment procedures. The dental specialist should also be

prepared to face any kind of emergencies which could arise

suddenly during treatment any procedure.

“Complications” may be immediate or delayed. They may not

be life threatening but always require attention and proper

protocols to be followed for effective management.

Conclusion

Emergencies cannot be totally prevented but can be managed

appropriately with thorough knowledge of the signs, symptoms,

and accurate treatment of the emergencies. Accomplishing this

depends on the combined effort of the dental specialist, staff,

[Downloaded free from http://www.jeed.in on Sunday, June 18, 2017, IP: 159.255.164.73]

Journal of Education and Ethics in Dentistry

January-June 2012 • Vol. 2 • Issue 1

18

Prasad, et al.: Emergencies, complications and their management

and immediate availability of the critical drugs and equipments

for the procedure. However, no drug can replace an efficiently

trained health care professional in managing an emergency but

an emergency drug kit and equipment does play an integral

role in the course and outcome of management of emergencies

and complications in interdisciplinary dental practice.

References

1. Morrison AD, Goodday RH. Preparing for medical emergencies in

dental office. J Can Dent Assoc 1999;65:284‑6.

2. Reed KL. Basic management of medical emergencies: Recognizing a

patient’s distress. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141 Suppl 1:20S‑24.

3. Malamed SF. Medical Emergencies in the Dental Office. 6

th

ed.

St. Louis: Mosby; 2007. p. 51‑92.

4. Medical emergencies and resuscitation: Standards for clinical practice

and training for dental practitioners and dental care professionals

in general dental practice. A statement from the Resuscitation

council (UK) July 2006;revised May 2008.

5. Emergencies. In: Scully C.,Cawson RA. Medical Problems in dentistry.

5th ed. 2005 .563‑70.

6. Tiwana KK, Mortan T, Tiwana PS. Aspiration and ingestion in dental

practice. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;35:1287‑91.

7. Gencoglu N, Helvacioglu D. Comparison of the different techniques

to remove fractured endodontic instruments from root canal systems.

Eur J Dent 2009;3:90‑5.

8. Grzanka A, Misio

łek H, Filipowska A, Miśkiewicz‑Orczyk K,

Jarz

ąb J. Adverse effects of local anaesthetic allergy, toxic reactions

or hypersensitivity. Anaesthesiol Intens Ther 2010;42:175‑8.

9. Johansson SG, Hourihane JO, Bousquet J, Bruijnzeel‑Koomen C,

Dreborg S, Haahtela T, et al. A revised nomenclature for allergy. an

EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force.

Allergy 2001;56:813‑24.

10. Thyssen JP, Menné T, Elberling J, Plaschke P, Johansen JD.

Hypersensitivity to local anaesthetics – update and proposal of

evaluation algorithm. Contact Dermatitis 2008;59:69‑78.

11. Roedig JJ, Shah J, Elayi CS, Miller CS. Interference of cardiac pacemaker

and implantable cardioverter‑defibrillator activity during electronic

dental devices use. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141:521‑6.

12. Lamas Pelayo J, Peñarrocha Diago M, Martí Bowen E, Peñarrocha

Diago M. Intraoperative complications during oral implantology. Med

Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2008;13:E239‑43.

13. Flanagan D. Important arterial supply of the mandible, control of an

arterial hemorrhage, and report of a hemorrhagic incident. J Oral

Implantol 2003;29:165‑73.

14. Niamtu J 3

rd

. Near fatal airway obstruction after routine implant

placement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod

2001;92:597‑600.

15. Kalpidis CD, Setayesh RM. Hemorrhaging associated with endosseous

implant placement in the anterior mandible: A review of the literature.

J Periodontol 2004;75:631‑45.

16. Guarinos J, Peñarrocha M, Donado A. Complicaciones y fracasos. In:

Peñarrocha M, editor. Implantología oral. Barcelona: Ars Médica;

2001. p. 245‑56.

(PHUJHQF\NLWFRPSRQHQWV

3KDUPDFRORJLFDODJHQWV

$LUZD\DFFHVVRULHV

ORDGHGLQD

V\ULQJH

(SLQHSKULQH

'LSKHQK\GUDPLQHRU

&KORUSKHQ\UDPLQH

0DOHDWH

$QWLKLVWDPLQH

'LD]HSDP

$QWLFRQYXOVDQW

'H[WURVH

*OXFDJRQ*OXFRVH

6XJDU

$QWLK\SRJ\OFHPLF

0RUSKLQHIRU0,

$QDOJHVLF

/LJQRFDLQH$WURSLQH

6DOEXWDPRO,QKDORU

2WKHUV

2[\JHQFRQFHQWUDWRU

6HWRIRURSKDU\QJHDO

DQGQDVRSKDU\QJHDO

DLUZD\V

1DVDO&DQXOD

)DFHPDVN

$0%8%$*

Figure 7: Emergency Kit Components

[Downloaded free from http://www.jeed.in on Sunday, June 18, 2017, IP: 159.255.164.73]

19

Journal of Education and Ethics in Dentistry

January-June 2012 • Vol. 2 • Issue 1

Prasad, et al.: Emergencies, complications and their management

17. Kim SG. Implant‑related damage to an adjacent tooth: A case report.

Implant Dent 2000;9:278‑80.

18. Tehemar SH. Factors affecting heat generation during implant

site preparation: A review of biologic observations and future

considerations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1999;14:127‑36.

19. Guisado B. Complicaciones y fracasos en implantología. In:

Bascones A, editor. Tratado de odontología. Tomo IV. Madrid:

Smithkline Beecham; 1998. p. 3877‑86.

20. Goodacre CJ, Bernal G, Rungcharassaeng K, Kan JY. Clinical

complications with implants and implant prostheses. J Prosthet Dent

2003;90:121‑32.

21. Available from: http://firstaid.about.com/od/cpr/qt/09_2010_CPR_

Guidelines.htm [Last accessed on 12.12.2011].

22. ADA Council on Scientific Affairs. Office emergencies and emergency

kits. J Am Dent Assoc 2002;133:364‑5.

How to cite this article: Prasad KD, Hegde C, Alva H, Shetty M.

Medical and dental emergencies and complications in dental practice

and its management. J Educ Ethics Dent 2012;2:13-9.

Source of Support: Nil, Conflict of Interest: None declared

Author Help: Reference checking facility

The manuscript system (www.journalonweb.com) allows the authors to check and verify the accuracy and style of references. The tool checks

the references with PubMed as per a predefined style. Authors are encouraged to use this facility, before submitting articles to the journal.

•

The style as well as bibliographic elements should be 100% accurate, to help get the references verified from the system. Even a

single spelling error or addition of issue number/month of publication will lead to an error when verifying the reference.

•

Example of a correct style

Sheahan P, O’leary G, Lee G, Fitzgibbon J. Cystic cervical metastases: Incidence and diagnosis using fine needle aspiration biopsy.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002;127:294-8.

•

Only the references from journals indexed in PubMed will be checked.

•

Enter each reference in new line, without a serial number.

•

Add up to a maximum of 15 references at a time.

•

If the reference is correct for its bibliographic elements and punctuations, it will be shown as CORRECT and a link to the correct

article in PubMed will be given.

•

If any of the bibliographic elements are missing, incorrect or extra (such as issue number), it will be shown as INCORRECT and link to

possible articles in PubMed will be given.

[Downloaded free from http://www.jeed.in on Sunday, June 18, 2017, IP: 159.255.164.73]