Chapter 2 - 1

Chapter 2: Atomic Structure and

Interatomic Bonding

Chapter 2 - 2

Chapter 2: Atomic Structure &

Interatomic Bonding

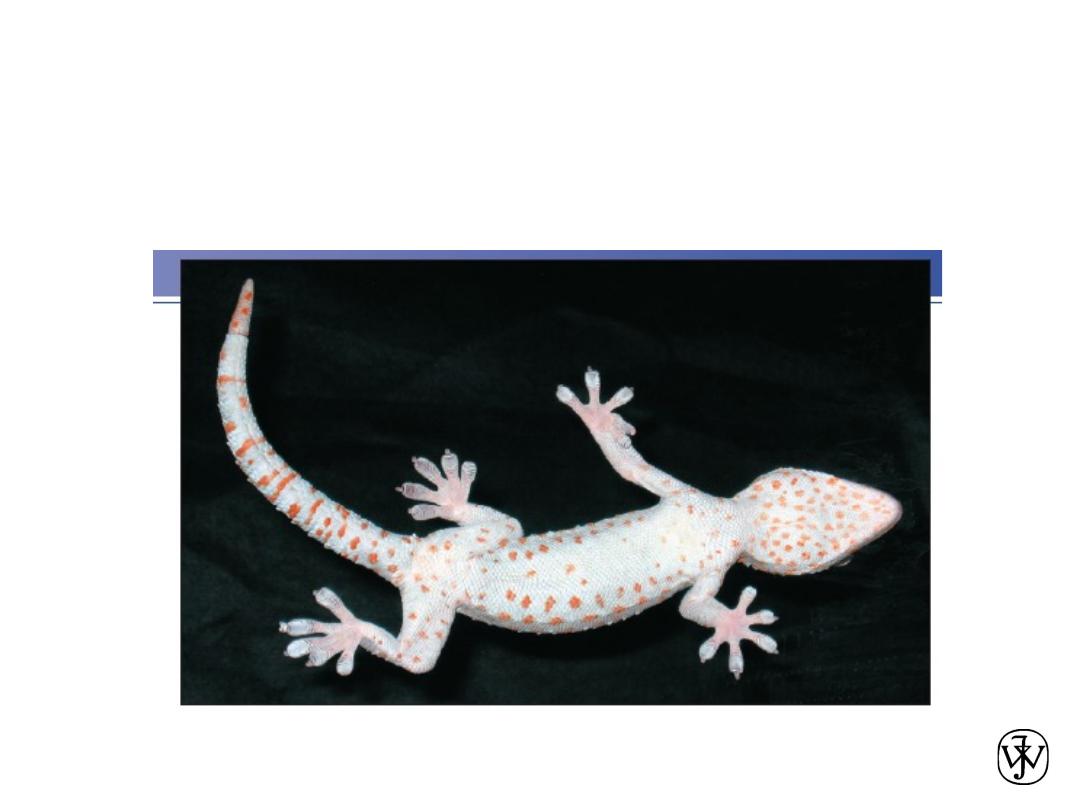

Geckos, harmless tropical lizards, are extremely

fascinating and extraordinary animals. They

have very sticky feet that cling to virtually any surface. This

characteristic makes it possible for

them to rapidly run up vertical walls and along the

undersides of horizontal surfaces. In fact, a

gecko can support its body mass with a single toe! The

secret to this remarkable ability is the presence

of an extremely large number of microscopically small

hairs on each of their toe pads. When

these hairs come in contact with a surface, weak forces of

attraction (i.e., van der Waals forces)

are established between hair molecules and molecules on

the surface.

Chapter 2 - 3

ISSUES TO ADDRESS...

• What promotes bonding?

• What types of bonds are there?

• What properties are inferred from bonding?

Chapter 2: Atomic Structure &

Interatomic Bonding

Chapter 2 - 4

Chapter 2: Atomic Structure &

Interatomic Bonding

Learning Objectives

1. Name the two atomic models cited, and note

the differences between them.

2. Describe the important quantum-mechanical

principle that relates to electron energies.

3. bonding energy.

4. ionic, covalent, metallic, hydrogen, and van der Waals

bonds.

Chapter 2 - 5

WHY STUDY Atomic Structure and

Interatomic Bonding?

An important reason to have an understanding of interatomic

bonding in solids is that, in some instances,

the type of bond allows us to explain a material’s

properties.

For example, consider carbon, which may

exist as both graphite and diamond. Whereas graphite

is relatively soft and has a “greasy” feel to it, diamond

is the hardest known material. This dramatic disparity

in properties is directly attributable to a type of interatomic

bonding found in graphite that does not exist

in diamond

Chapter 2 - 6

Some of the important properties of solid materials depend on

geometrical atomic arrangements, and also the interactions that

exist among constituent atoms or molecules.

• atomic structure,

• Electron configurations in atoms

• the periodic table

• the various types of primary and secondary interatomic

bonds

Chapter 2 -

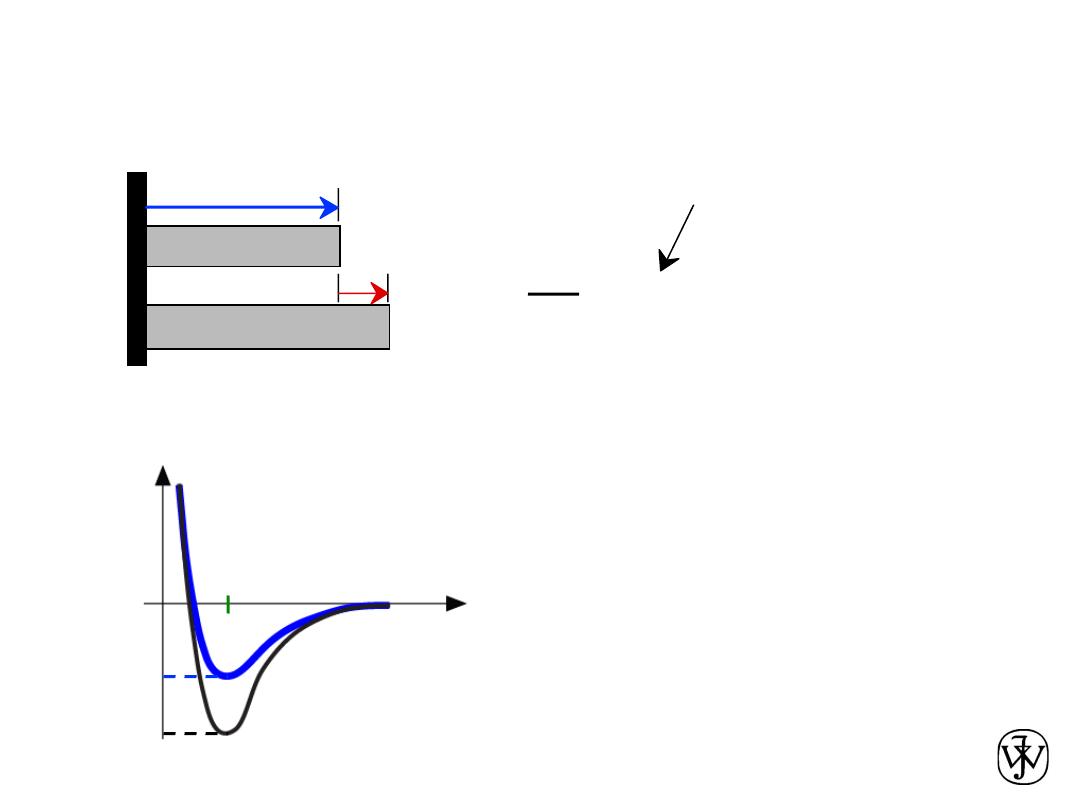

Wavelike behavior of electrons

• We often use dots to represent individual electrons and lines for

pairs of electrons in a covalent bond.

• However, the electrons have a wavelike behavior such that we

can only give the probability of an electron being in a particular

volume.

• So a more accurate representation of an electron is as a cloud.

7

Chapter 2 - 8

A set of principles and laws that govern systems of

atomic and subatomic entities that came to be known

as quantum mechanics.

An understanding of the behavior of electrons in atoms

and

crystalline

solids

necessarily

involves

the

discussion of quantum-mechanical concepts.

Chapter 2 - 9

An important quantum-mechanical principle stipulates that

the energies of electrons are quantized;; that is, electrons are

permitted to have only specific values of energy.

An electron may change energy, but in doing so it must make

a quantum jump either to an allowed higher energy (with

absorption of energy) or to a lower energy (with emission of

energy).

Often, it is convenient to think of these allowed

electron energies as being associated with energy levels or

states. These states do not vary continuously with energy;; that

is, adjacent states are separated by finite energies.

Chapter 2 - 10

Atomic Structure

• Each chemical element is characterized by the number

of protons in the nucleus, or the atomic number (Z).

(for an electrically neutral atom also equals to number of

electrons)

• The atomic mass (A) of a specific atom may be

expressed as the sum of the masses of protons and

neutrons within the nucleus.

• Atoms of some elements have two or more different

atomic masses, which are called isotopes.

• The atomic weight of an element corresponds to the

weighted average of the atomic masses of the atom’s

naturally occurring isotopes.

• The atomic mass unit (amu) may be used for

computations of atomic weight.

Chapter 2 - 11

Atomic Structure

• atom –

electrons

– 9.11 x 10

-31

kg

protons

neutrons

• Charge magnitude of electrons and protons

• 1.60 x 10

-19

C

• atomic number

= # of protons in nucleus of atom

= # of electrons of neutral species

• A [=]

atomic mass unit

= amu = 1/12 mass of

12

C

Atomic wt

= wt of 6.022 x 10

23

molecules or atoms

1 amu/atom = 1g/mol

C 12.011

H 1.008 etc.

}

1.67 x 10

-27

kg

Chapter 2 - 12

number of neutrons = N

number of protons = Z

A= Z + N

(

2.1)

AVAGADRO’S NUMBER = 6.022 x 10

23

= N

A

ATOMIC OR MOLECULAR WEIGHT =

N

A

x WEIGHT PER ATOM.

Chapter 2 - 13

Atomic Structure

• Valence electrons determine all of the

following properties

1) Chemical

2) Electrical

3) Thermal

4) Optical

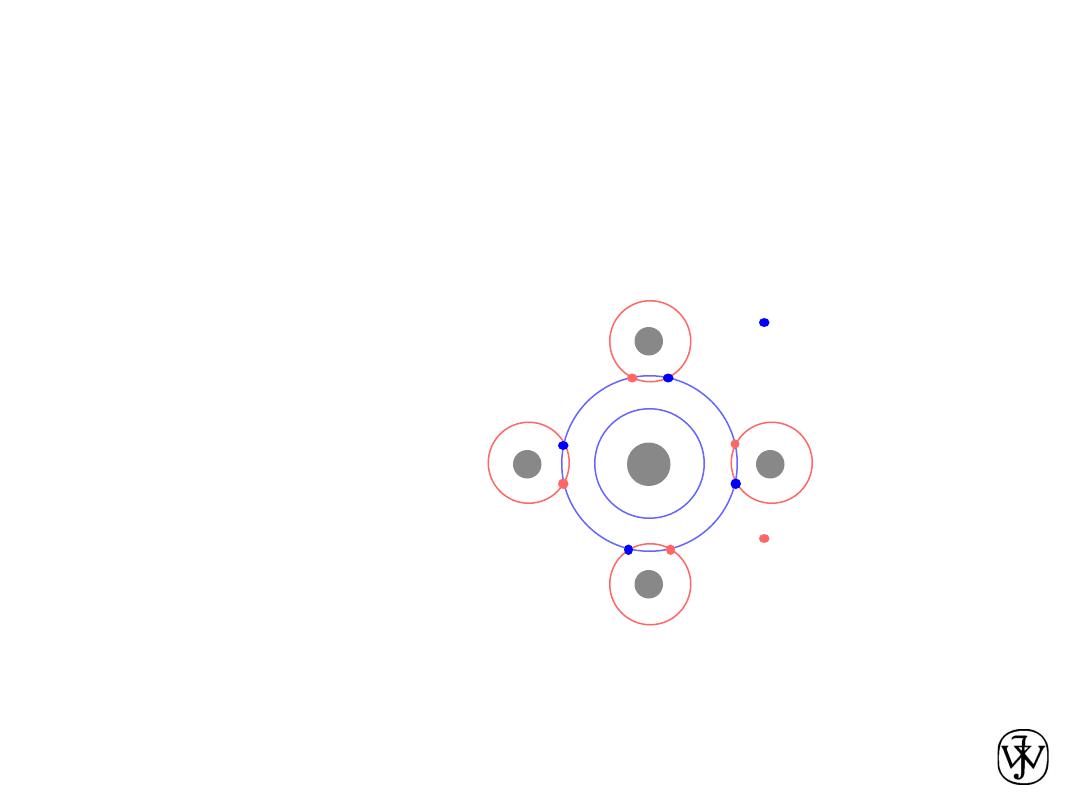

Chapter 2 -

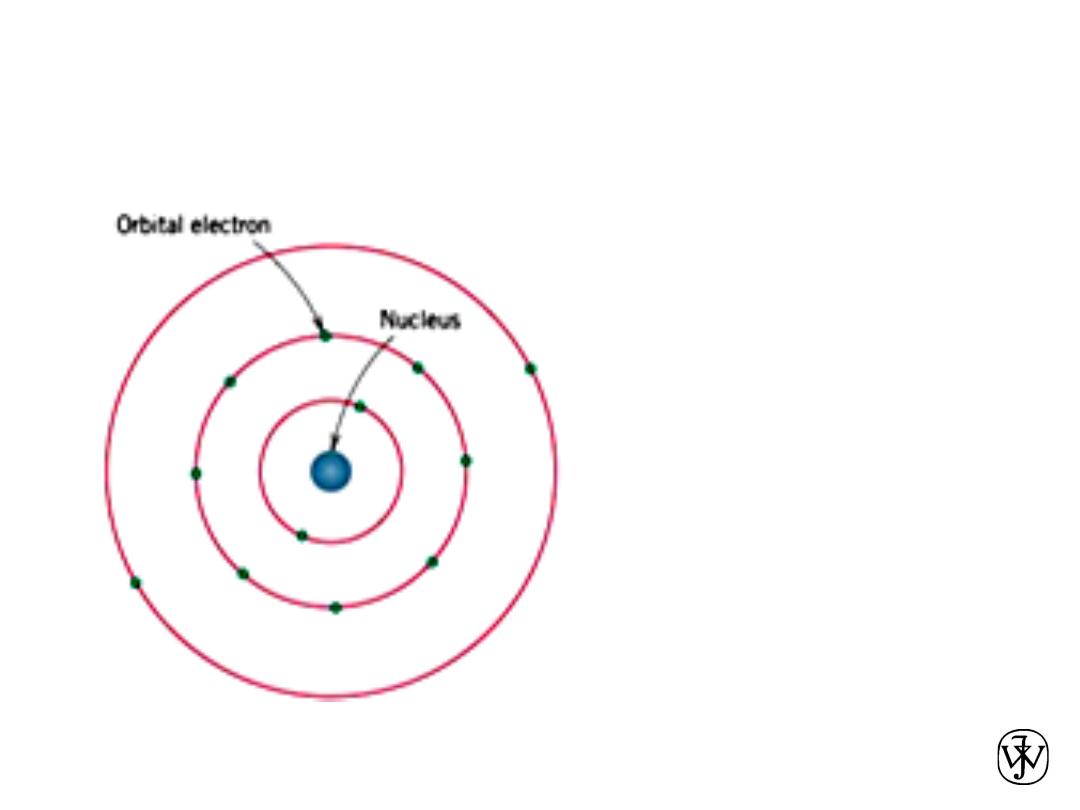

BOHR ATOM

14

Bohr atomic

model, in which

electrons are assumed

to revolve around the

atomic nucleus

in discrete orbitals, and

the position of any

particular electron is

more or

less well defined in

terms of its orbital.

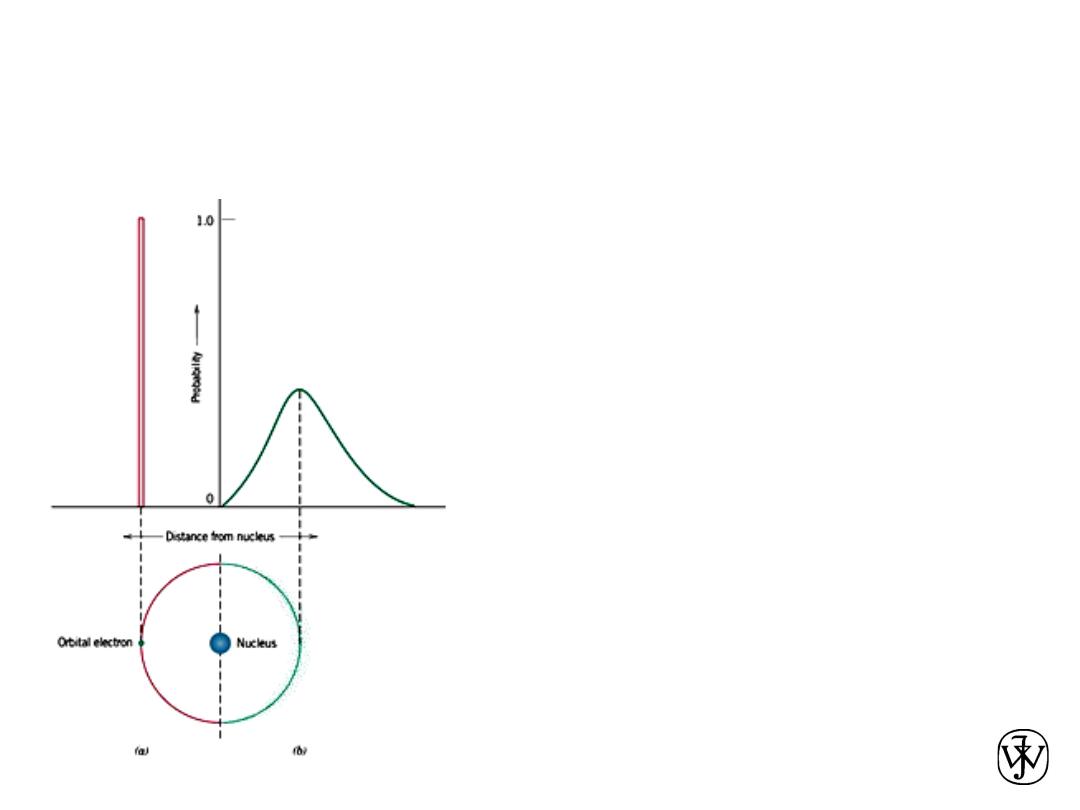

Chapter 2 -

WAVE MECHANICAL MODEL OF

ATOM

15

This Bohr model was eventually found to

have some significant limitations

because of its inability to explain several

phenomena involving electrons. A

resolution was reached with a

wave-

mechanical model,

in which the electron is

considered to exhibit both wave-like and

particle-like characteristics. With this

model, an electron is no longer treated as a

particle moving in a discrete orbital;

rather, position is considered to be the

probability of an electron’s being at

various locations around the nucleus. In other

words, position is described by a

probability distribution or electron cloud.

Chapter 2 - 16

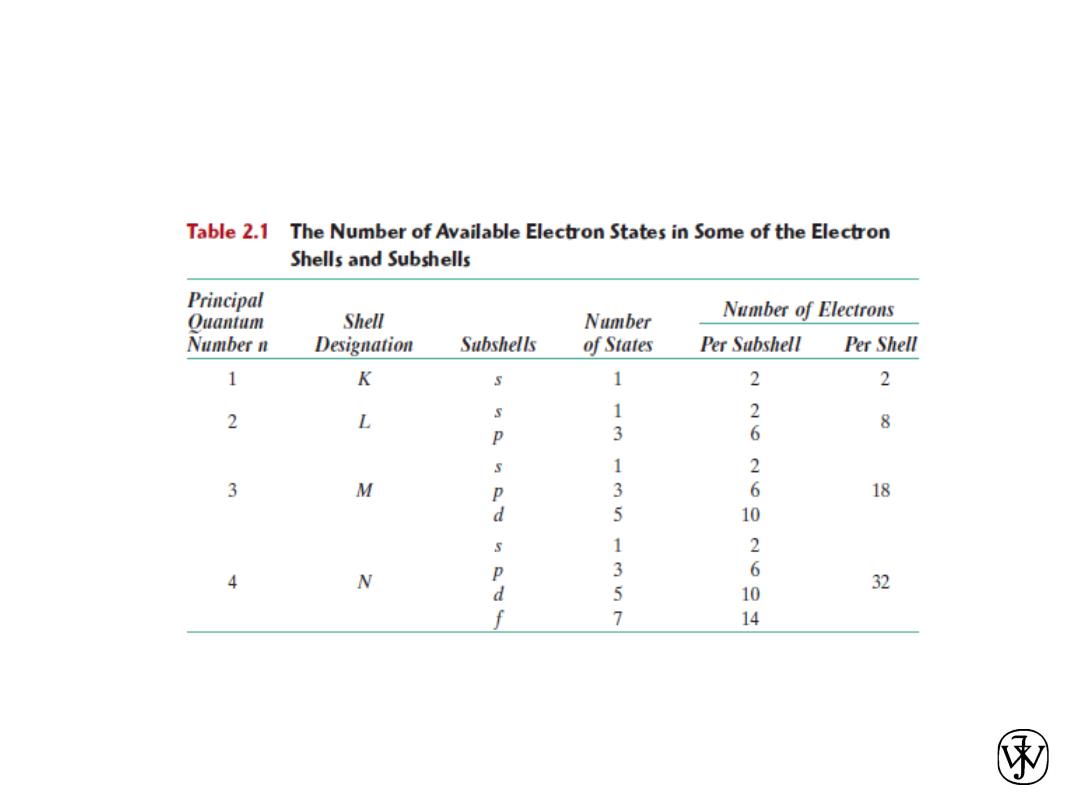

Electronic structure of isolated atoms

• The characteristics below stem from their wavelike nature.

– electrons are in orbitals

– each orbital is at a discrete energy level determined by its quantum

numbers

– the letter designations below were given to bands observed in optical

emission and absorption, but not understood at the time.

Quantum Number

Designation

n = principal (energy level-shell)

1,2,3,4,5,6,7 (K, L, M, N, O,…)

l = angular (sub shell, shape)

s, p, d, f (n of them to max of 4)

m

l

= magnetic

- l to + l by integers, including 0

m

s

= spin

½, -½

v

Dynamic periodic table

v

Atomic orbitals

Chapter 2 - 17

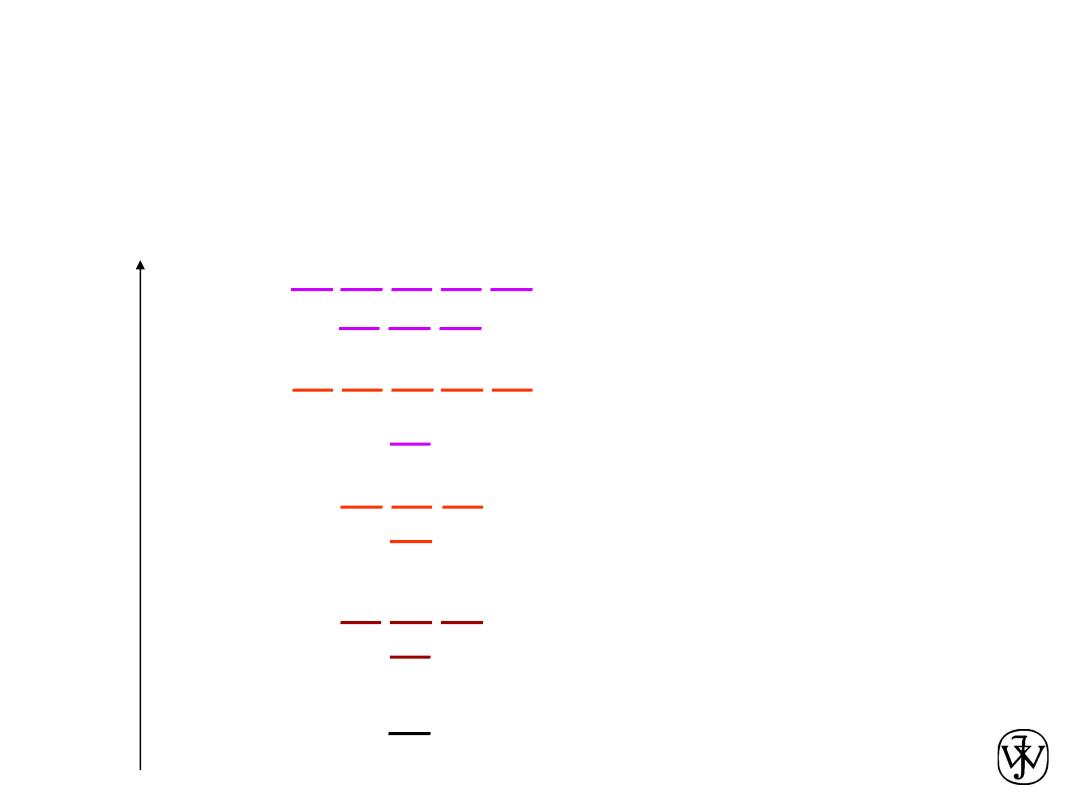

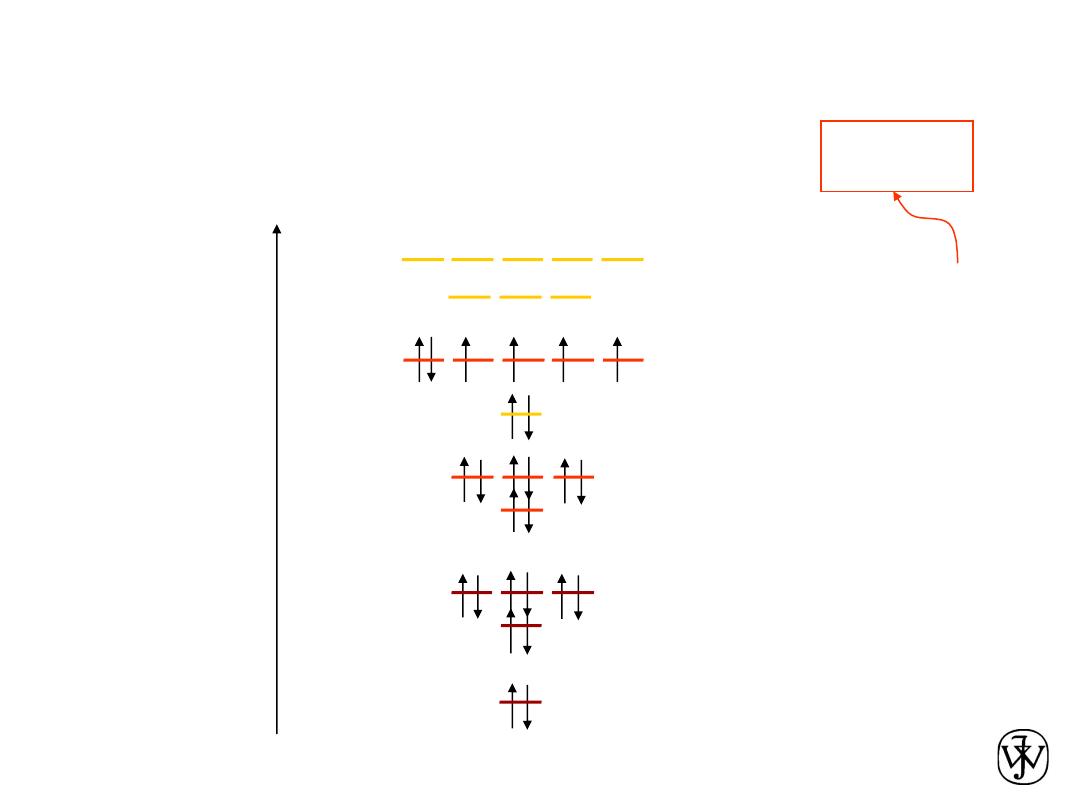

Electron energy states of isolated atoms

1s

2s

2p

K-shell n = 1

L-shell n = 2

3s

3p

M-shell n = 3

3d

4s

4p

4d

Energy

N-shell n = 4

Electrons have discrete energy states. They occupy the lowest

possible energy levels, unless excited by an external source of energy,

e.g. thermal energy or absorption of photons (in light).

Two electrons of

opposite spin can

be in each level.

Chapter 2 - 18

The electron configuration is stable only for the noble gases. Except

for noble gases, the outer shell is not completely filled and so one or

more electrons may be lost or gained to form an ion,

or shared in a covalent bond.

Ground-state energy levels of some elements

Electron configuration

(stable)

...

...

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

3s

2

3p

6

(stable)

...

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

3s

2

3p

6

3d

10

4s

2

4p

6

(stable)

Atomic #

18

...

36

Element

1s

1

1

Hydrogen

1s

2

2

Helium

1s

2

2s

1

3

Lithium

1s

2

2s

2

4

Beryllium

1s

2

2s

2

2p

1

5

Boron

1s

2

2s

2

2p

2

6

Carbon

...

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

(stable)

10

Neon

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

3s

1

11

Sodium

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

3s

2

12

Magnesium

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

3s

2

3p

1

13

Aluminum

...

Argon

...

Krypton

Chapter 2 - 19

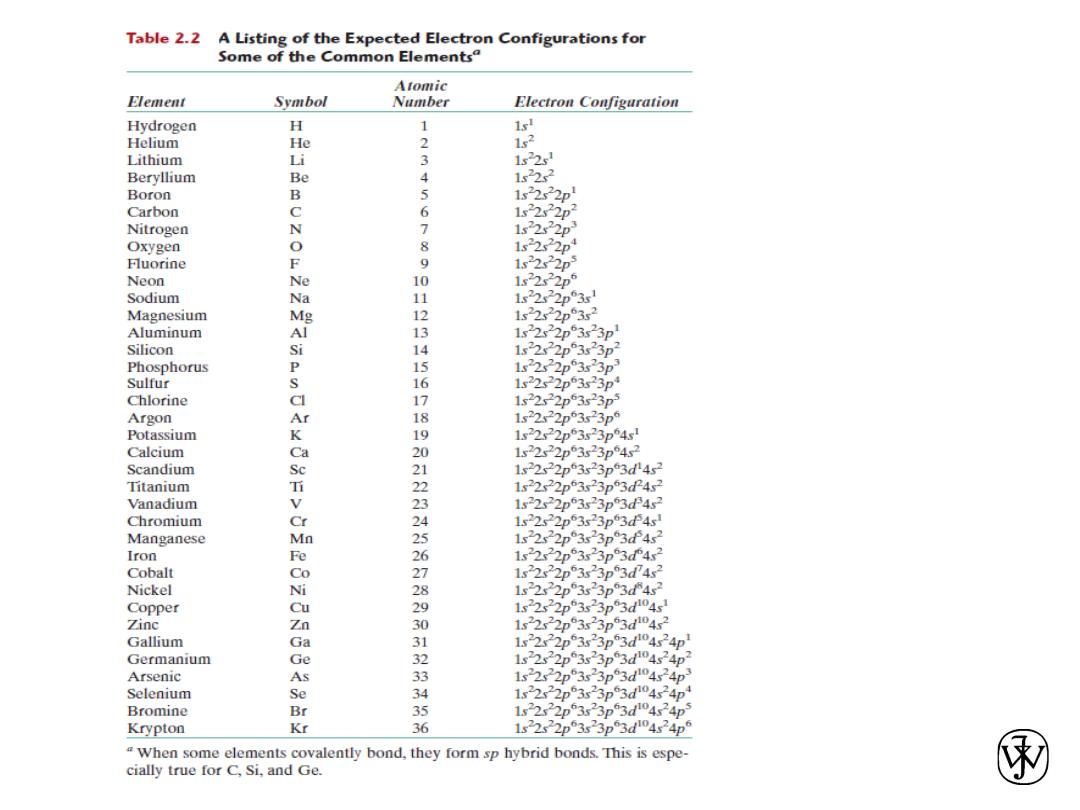

Electron Configurations

• Valence electrons

– those in unfilled shells

• Filled shells more stable

• Valence electrons are most available for

bonding and tend to control the chemical

properties

– example: C (atomic number = 6)

1s

2

2s

2

2p

2

valence electrons

Chapter 2 - 20

Electronic Configurations

ex: Fe - atomic #

=

26

valence

electrons

Adapted from Fig. 2.4,

Callister & Rethwisch 8e.

1s

2s

2p

K-shell n = 1

L-shell n = 2

3s

3p

M-shell n = 3

3d

4s

4p

4d

Energy

N-shell n = 4

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

3s

2

3p

6

3d

6

4s

2

Chapter 2 - 21

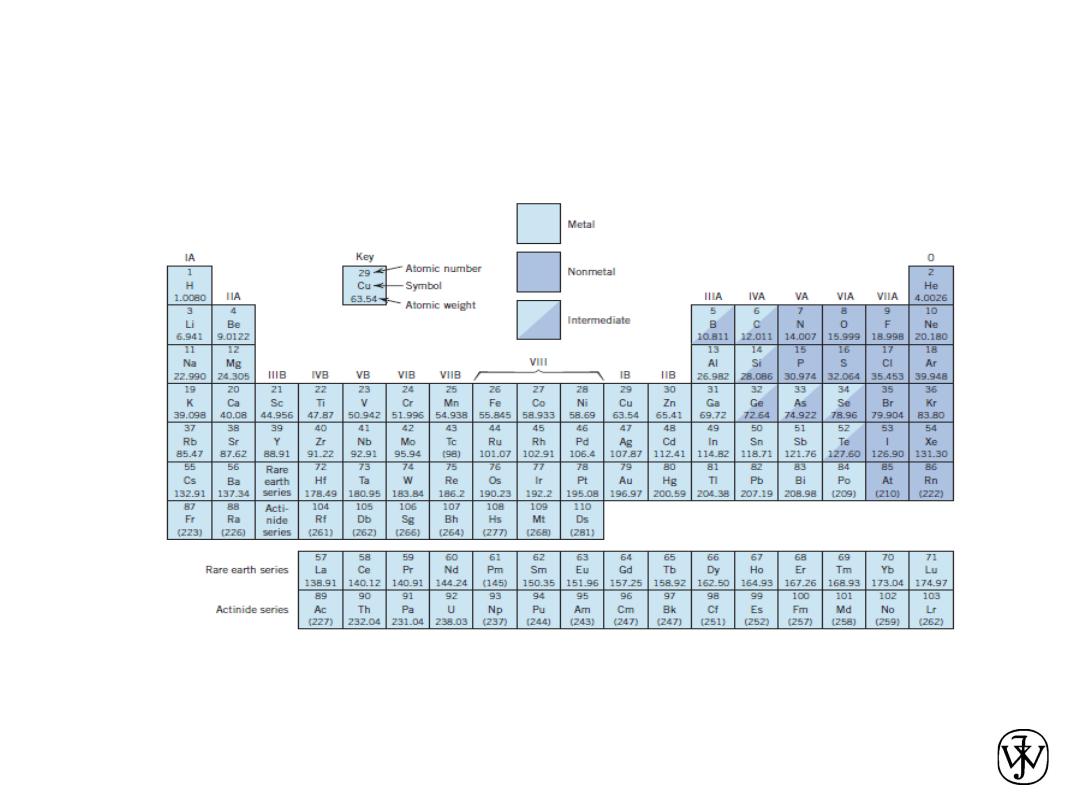

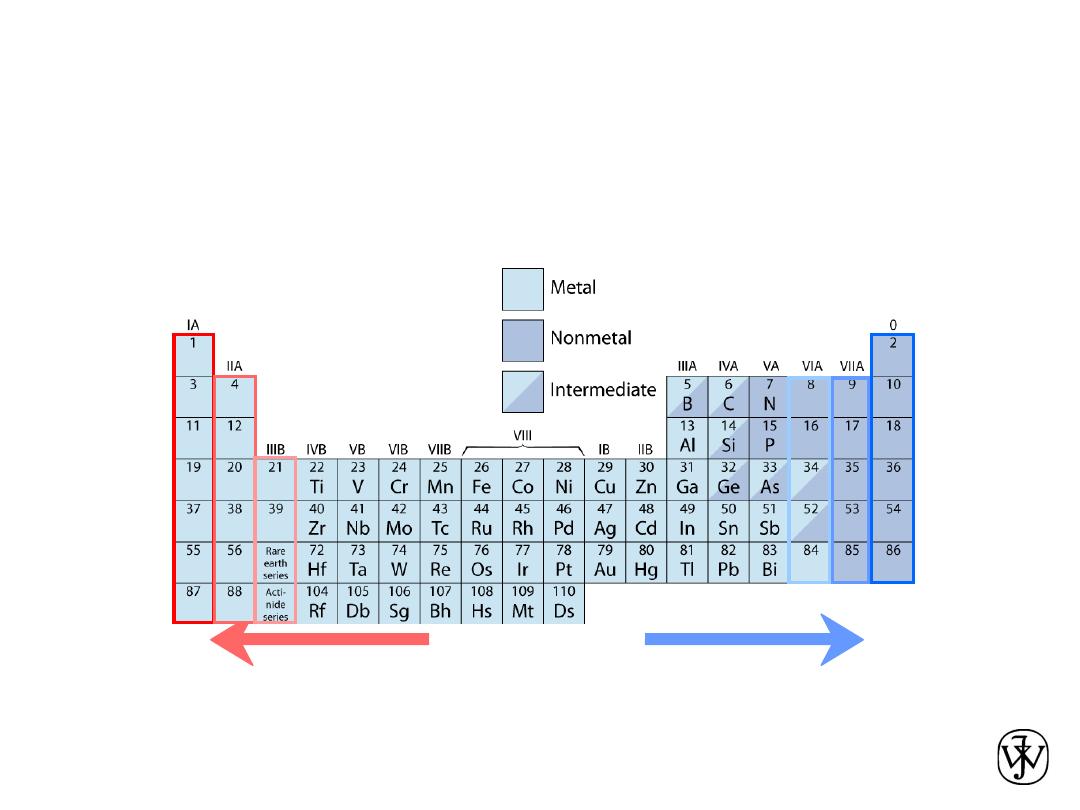

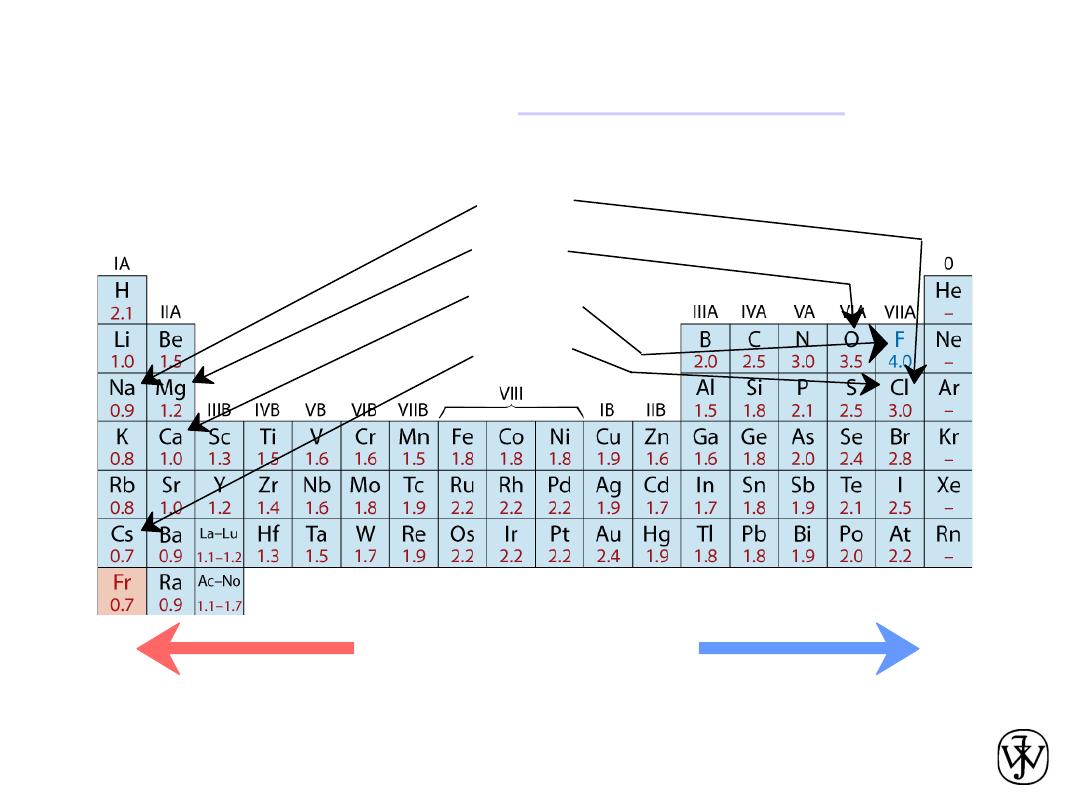

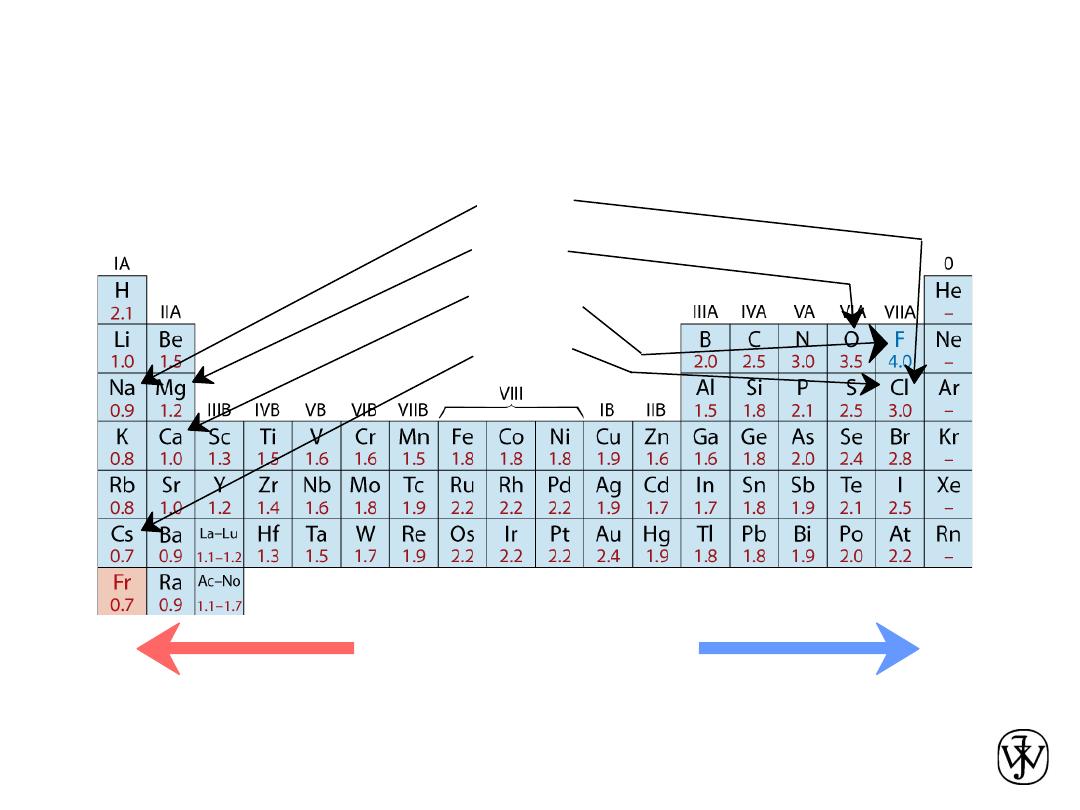

The Periodic Table

All the elements have been classified according to electron

configuration in the periodic table.

The elements are situated, with increasing atomic number, in

seven horizontal rows called periods.

The arrangement is such that all elements arrayed in a given

column or group have similar valence electron structures, as

well as chemical and physical properties.

These properties change gradually, moving horizontally

across each period and vertically down each column.

Chapter 2 - 22

The Periodic Table

Chapter 2 - 23

The Periodic Table

• Columns:

Similar

Valence

Structure

Adapted from

Fig. 2.6,

Callister &

Rethwisch 8e.

Electropositive elements:

Readily give up electrons

to become + ions.

Electronegative elements:

Readily acquire electrons

to become - ions.

gi

ve

u

p

1e

-

gi

ve

u

p

2e

-

gi

ve

u

p

3e

-

in

er

t g

ase

s

acce

pt

1

e

-

acce

pt

2

e

-

O

Se

Te

Po At

I

Br

He

Ne

Ar

Kr

Xe

Rn

F

Cl

S

Li

Be

H

Na

Mg

Ba

Cs

Ra

Fr

Ca

K

Sc

Sr

Rb

Y

Chapter 2 -

• electropositive elements,indicating that

they are capable of giving up their few

valence electrons to become positively

charged ions.

• the elements situated on the right-hand

side of the table are electronegative;;

that is, they readily accept electrons to

form negatively charged ions, or

sometimes they share electrons with

other atoms.

24

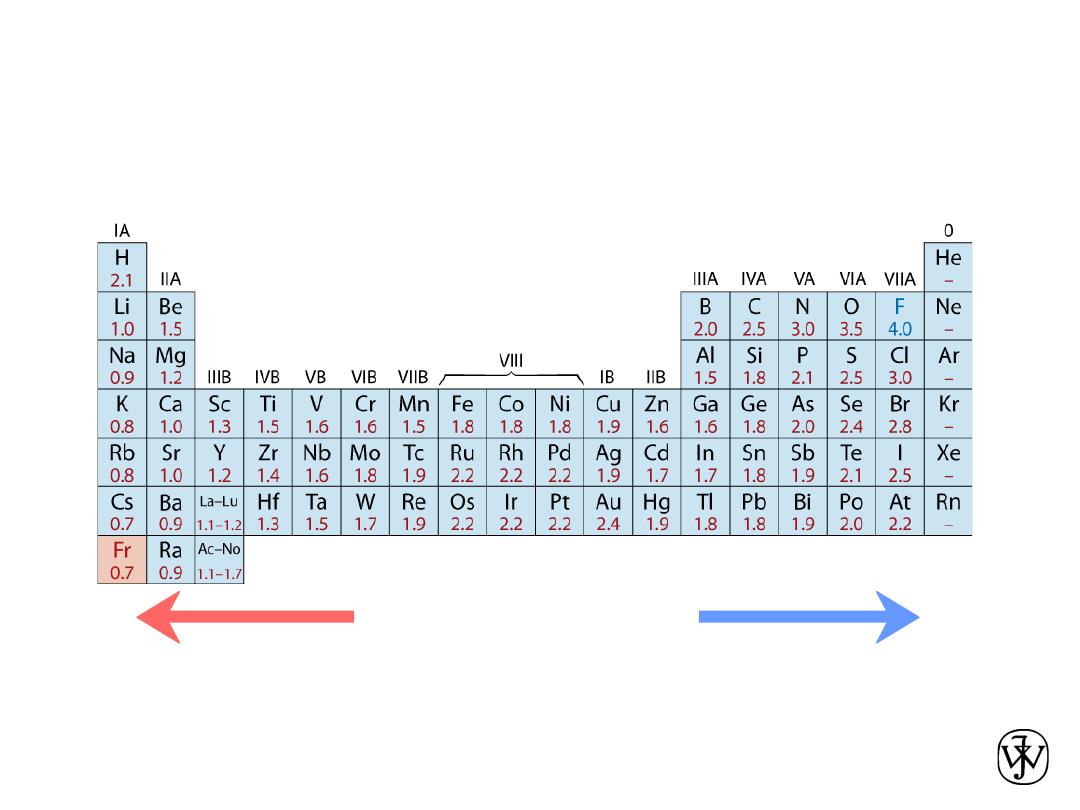

Chapter 2 - 25

• Ranges from

0.7

to

4.0

,

Smaller electronegativity

Larger electronegativity

• Large values: tendency to acquire electrons.

Adapted from Fig. 2.7, Callister & Rethwisch 8e. (Fig. 2.7 is adapted from Linus Pauling, The Nature of the

Chemical Bond, 3rd edition, Copyright 1939 and 1940, 3rd edition. Copyright 1960 by Cornell University.

Electronegativity

Chapter 2 - 26

Ionic bond –

metal

+ nonmetal

donates accepts

electrons electrons

Dissimilar electronegativities

ex:

Mg

O

Mg

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

3s

2

O

1s

2

2s

2

2p

4

[Ne] 3s

2

Mg

2+

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

O

2-

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

[Ne]

[Ne]

Chapter 2 -

Electrons in different shells

27

Chapter 2 - 28

Chapter 2 -

Atomic Bonding in Solids

• An understanding of many of the

physical properties of materials is

predicated on a knowledge of the

interatomic forces that bind the atoms

together.

• Perhaps

the

principles

of

atomic

bonding

are

best

illustrated

by

considering the interaction between two

isolated atoms as they are brought into

close

proximity

from

an

infinite

separation.

29

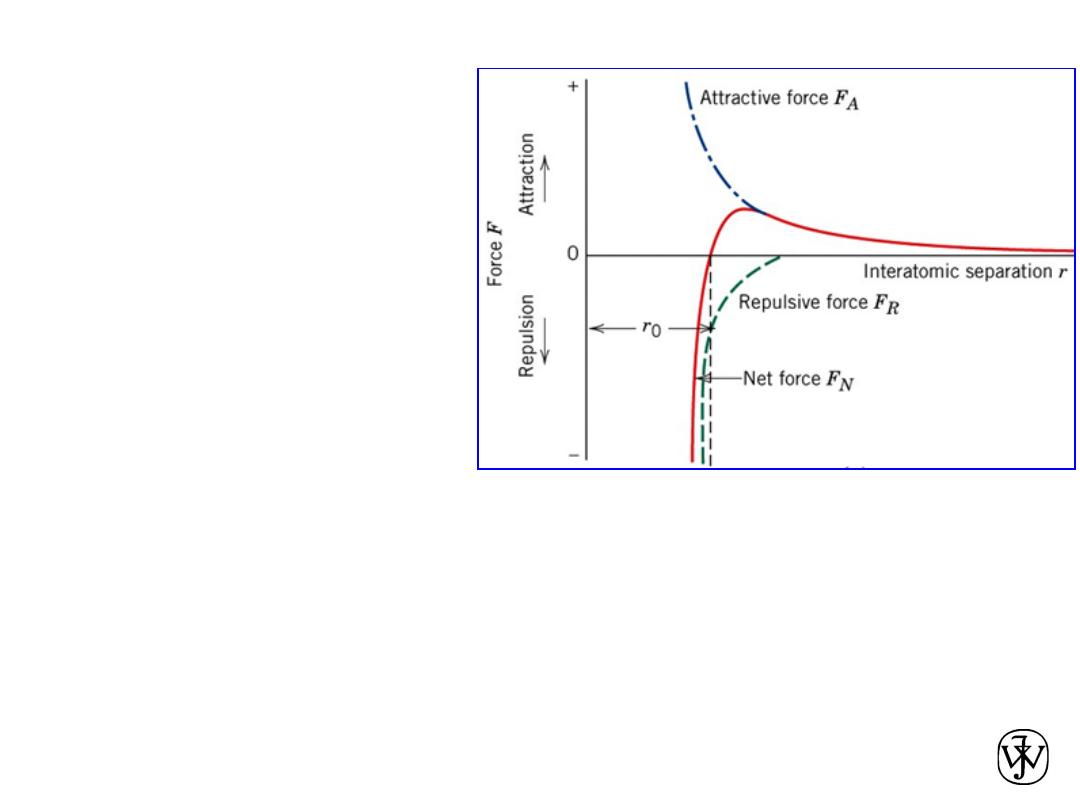

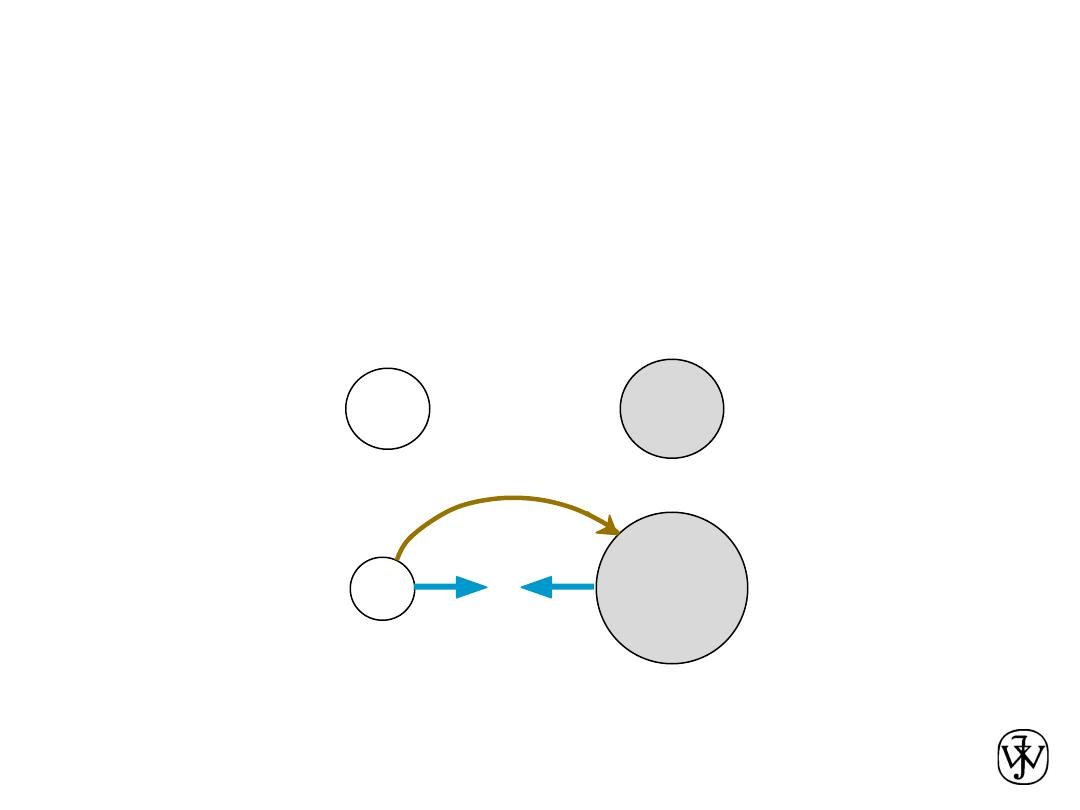

Chapter 2 -

Atomic Bonding in Solids

• At large distances, the interactions are

negligible, but as the atoms approach,

each exerts forces on the other. These

forces are of two types, attractive and

repulsive, and the magnitude of each is

a

function

of

the

separation

or

interatomic distance.

30

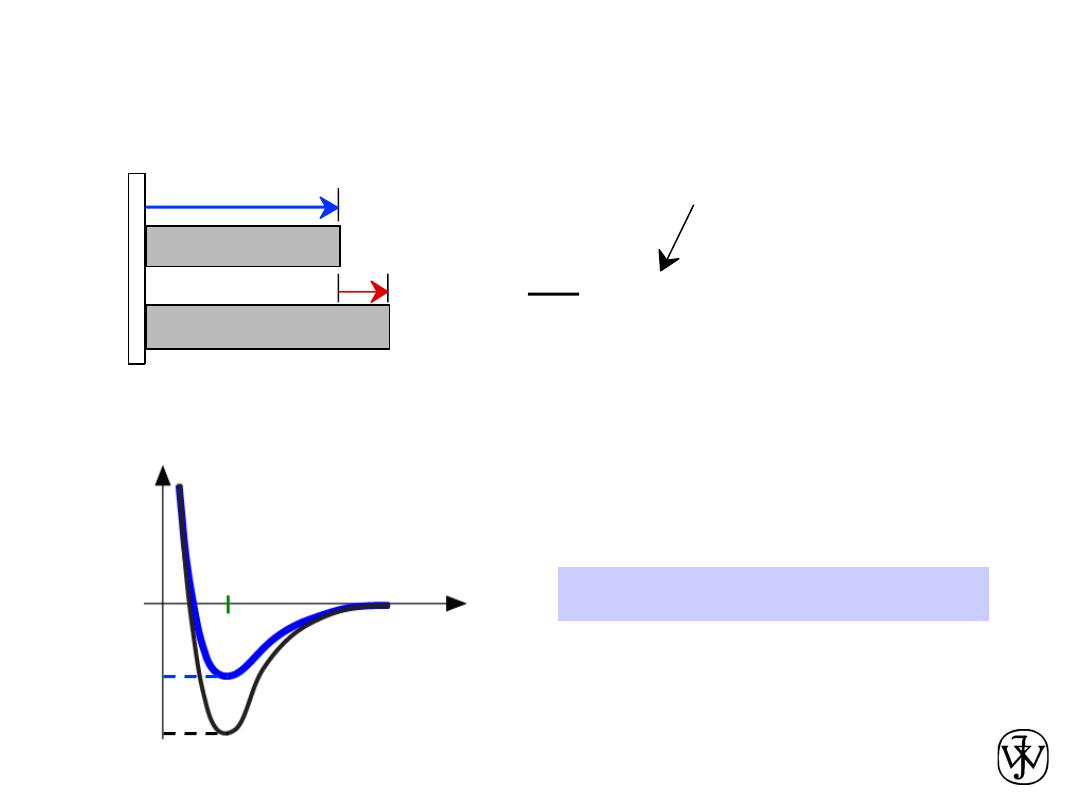

Chapter 2 -

Bonding in solids

• As two atoms approach one

another, they at first

experience an attraction.

• They repel one another when

they are brought very close.

• r

0

is the equilibrium distance.

• The type of bonding in a solid

depends on the behavior of the

atoms' outer “valence”

electrons.

• Metallic: outer electrons shared in a cloud or sea.

• Ionic

– Cations have given up one or more electrons

– Anions have gained one or more electrons

• Covalent: atoms share outer electrons

• Mixed ionic and covalent

• Van der Waals: electrostatic due to non-uniform charge distribution. Weak

Chapter 2 -

Typical ionic bond:

metal

+ nonmetal

Mg 1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

3s

2

O

1s

2

2s

2

2p

4

(Ne + 3s

2

)

(Ne – 2p

2

)

Mg

2+

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

O

2-

1s

2

2s

2

2p

6

(Ne)

(Ne)

cation

anion

donates

electrons

accepts

electrons

• The greater the difference in electronegativity, the greater the tendency to

form an ionic bond.

• Consider magnesium and oxygen with electronegativities of 1.31 and 3.44.

• Here’s what happens when Mg and O come near one another:

electron(s)

+

-

Coulombic

Attraction

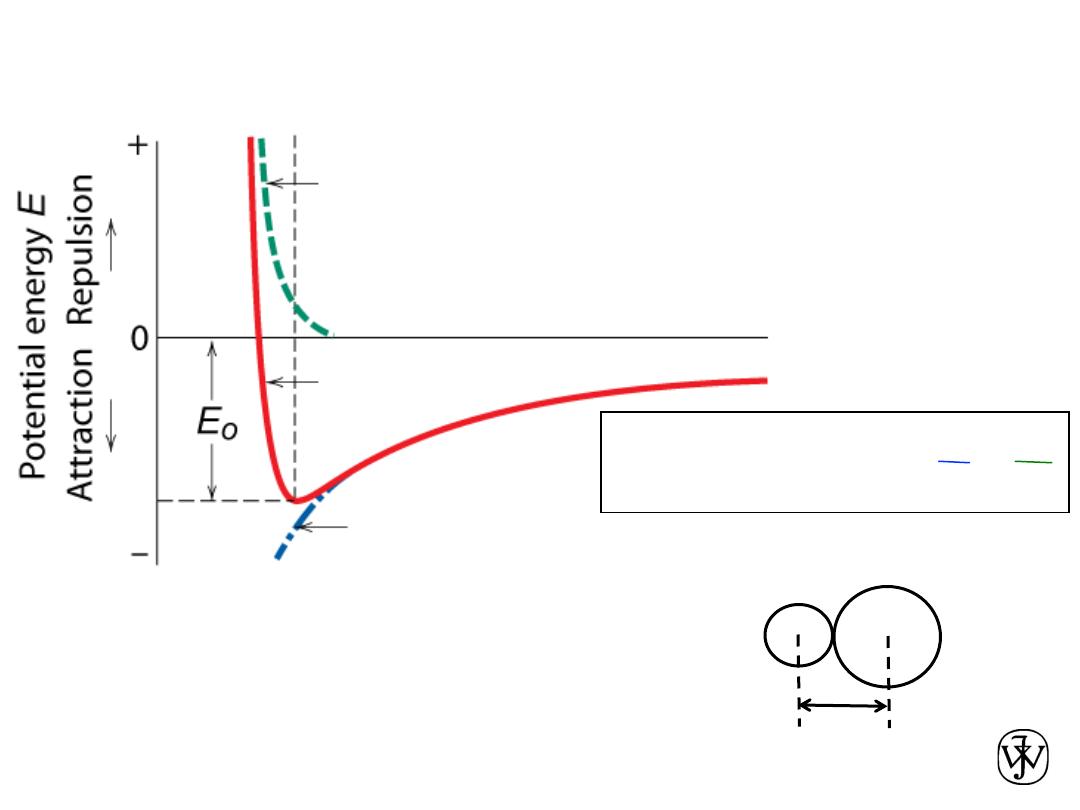

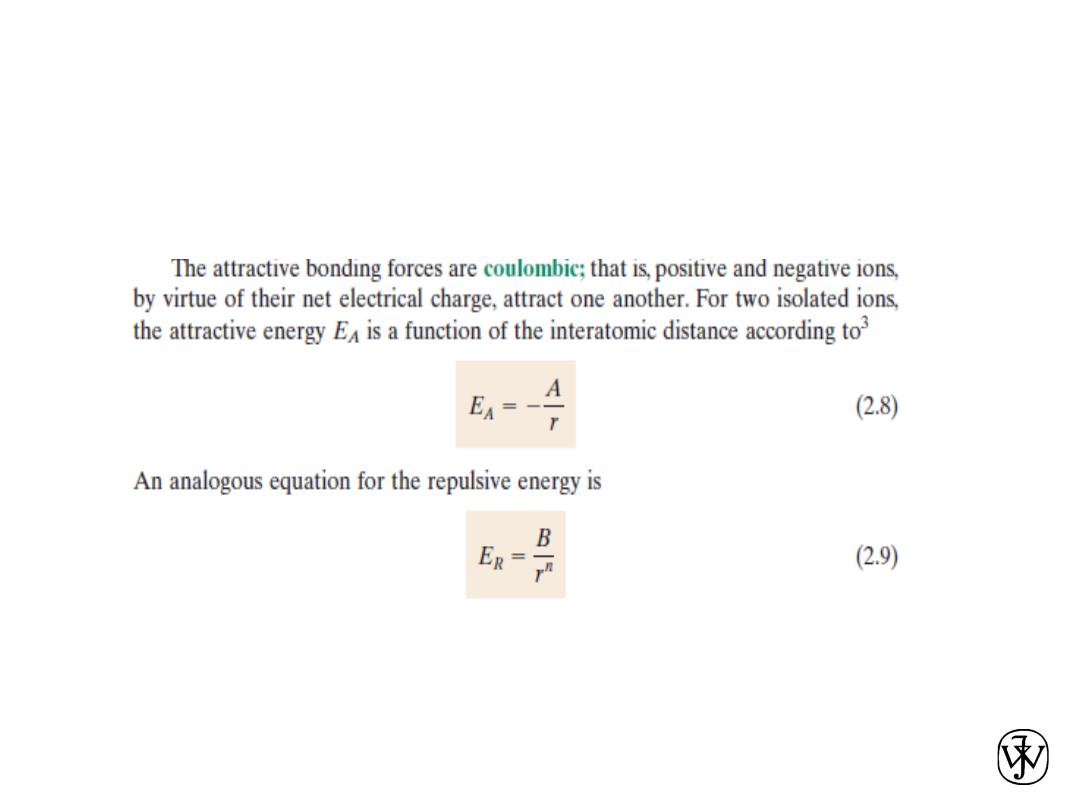

Chapter 2 - 33

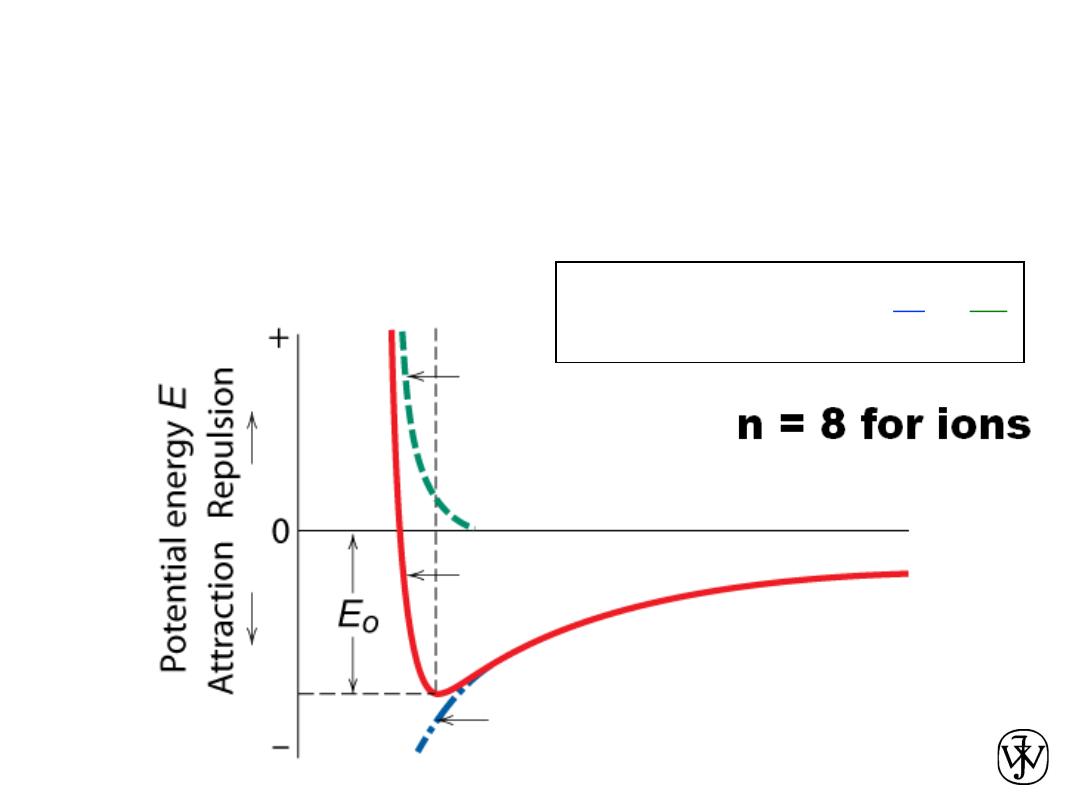

Ionic bonding between one cation (+)

and one anion (-)

Stable at minimum energy E

0

for radius r

0

.

Attractive energy E

A

Net energy E

N

Repulsive energy E

R

Interatomic separation r

r

0

r

A

n

r

B

E

N

=

E

A

+

E

R

=

+

-

r

0

Force = dE/dr = 0 at r

0

Chapter 2 - 34

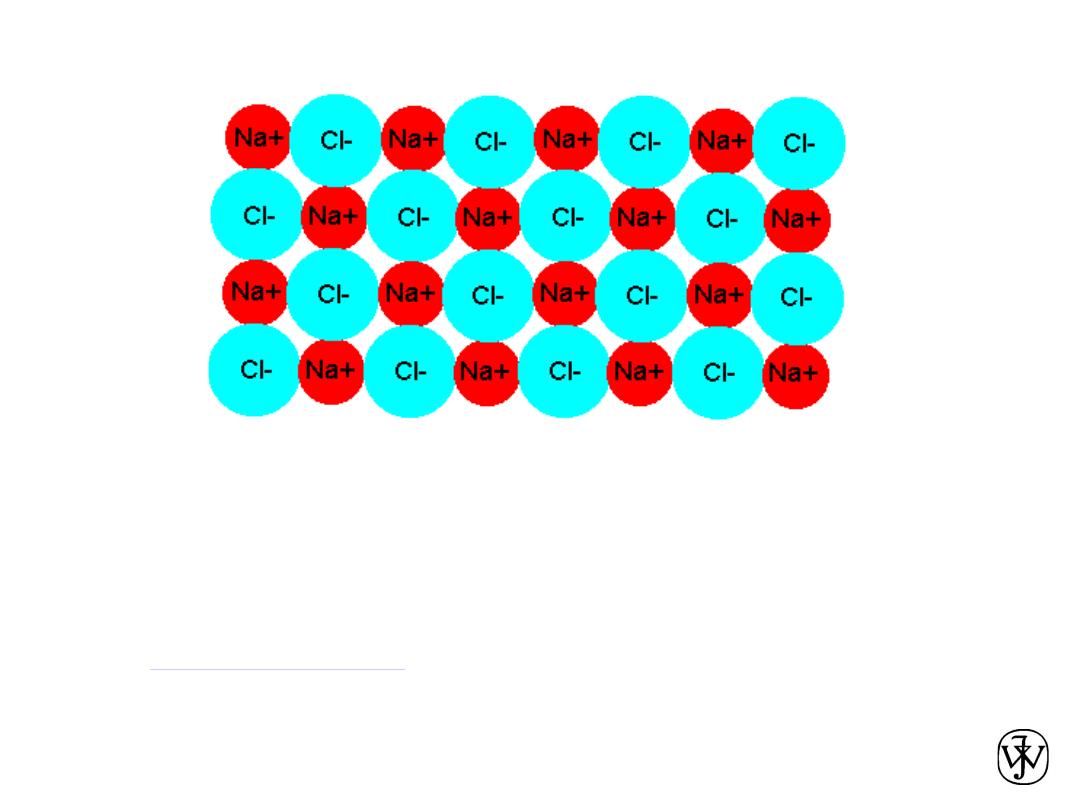

• Predominant bonding in Ceramics

Adapted from Fig. 2.7, Callister & Rethwisch 4e. (Fig. 2.7 is adapted from Linus Pauling, The Nature of the

Chemical Bond, 3rd edition, Copyright 1939 and 1940, 3rd edition. Copyright 1960 by Cornell University.

Examples:

Ionic Bonding

Give up electrons

Acquire electrons

NaCl

MgO

CaF2

CsCl

Chapter 2 -

Ionic bonding in a crystal

• In a crystal, a cation (+ charge) is attracted not only by the nearest

anions, but to a lesser extent by those farther away.

• Similarly, it is repelled by all other cations.

• The sum of the energy due to all attractions and repulsions is known

as the

Madelung energy

. This is approximately 60% greater than the

energy of attraction for isolated ions the same distance apart as in

the lattice.

35

Chapter 2 -

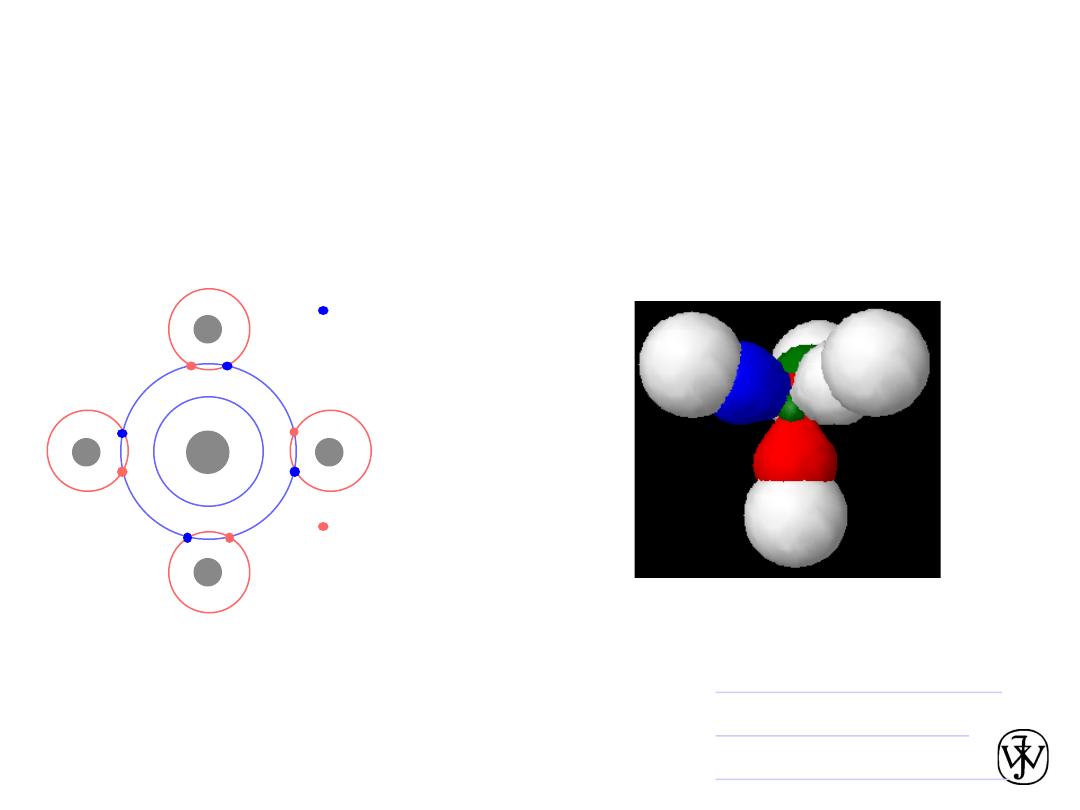

Covalent Chemical Bonds

• Atoms with almost the same electronegativity share electrons

leading to hybrid electronic structures.

• The bonds are very directional, unlike ionic bonds.

• Example:

shared electrons

from carbon atom

shared electrons

from hydrogen

atoms

H

H

H

H

C

CH4

v

Methane orbitals

•

Hybrid orbitals

v

Covalent orbitals

Chapter 2 -

Mixed Ionic-Covalent Bonding

• Ionic-Covalent Mixed Bonding

• Approximate fraction ionic character

»

where X

A

& X

B

are the two Pauling electronegativities.

÷

÷

ø

ö

ç

ç

è

æ

-

-

-

4

2

1

)

X

X

(

B

A

e

Example: MgO. Using the 1960 values in the text,

X

Mg

= 1.2 and X

O

= 3.5,

the equation above predicts that the bond between Mg and O has

about 73% ionic character and 27% covalent.

Using the revised values given on Wikipedia,

X

Mg

= 1.31 and X

O

= 3.44,

the equation above predicts that the bond between Mg and O has

about 68% ionic character and 32% covalent.

For homework problems use the values in the text.

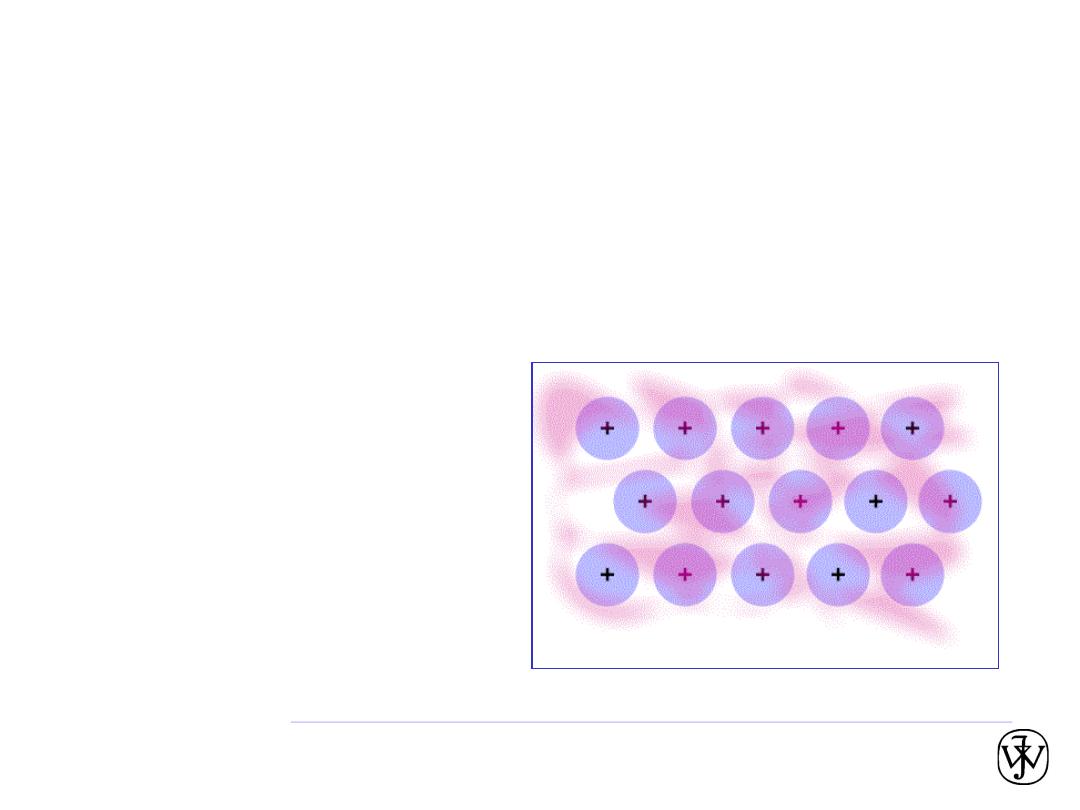

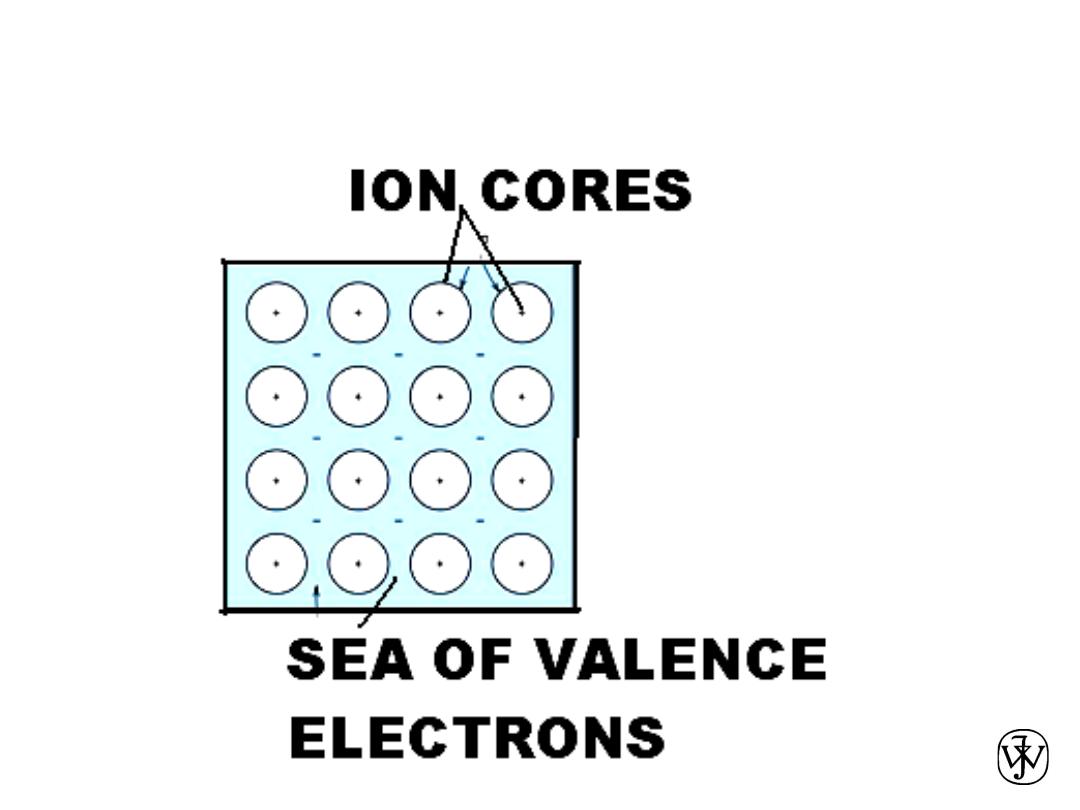

Chapter 2 -

Metallic bonding

• Occurs with atoms that easily give up electrons.

• In a solid, these “conduction” electrons form a cloud or sea.

• No two electrons can have exactly the same quantum number, and

so they have a range of energies. Each “exists” throughout the solid.

• The attraction between the positively charged metal ions and the

electron cloud is what causes metallic bonding.

• Non directional.

• These “conduction” electrons

carry electric current and heat.

• Mixtures of metals sometimes

form intermetallic compounds.

• Animation (in full-screen

projection mode):

38

Another animation:

http://mypchem.com/myp9/myp9c/myp9c_swf/metal_vib.htm

Chapter 2 -

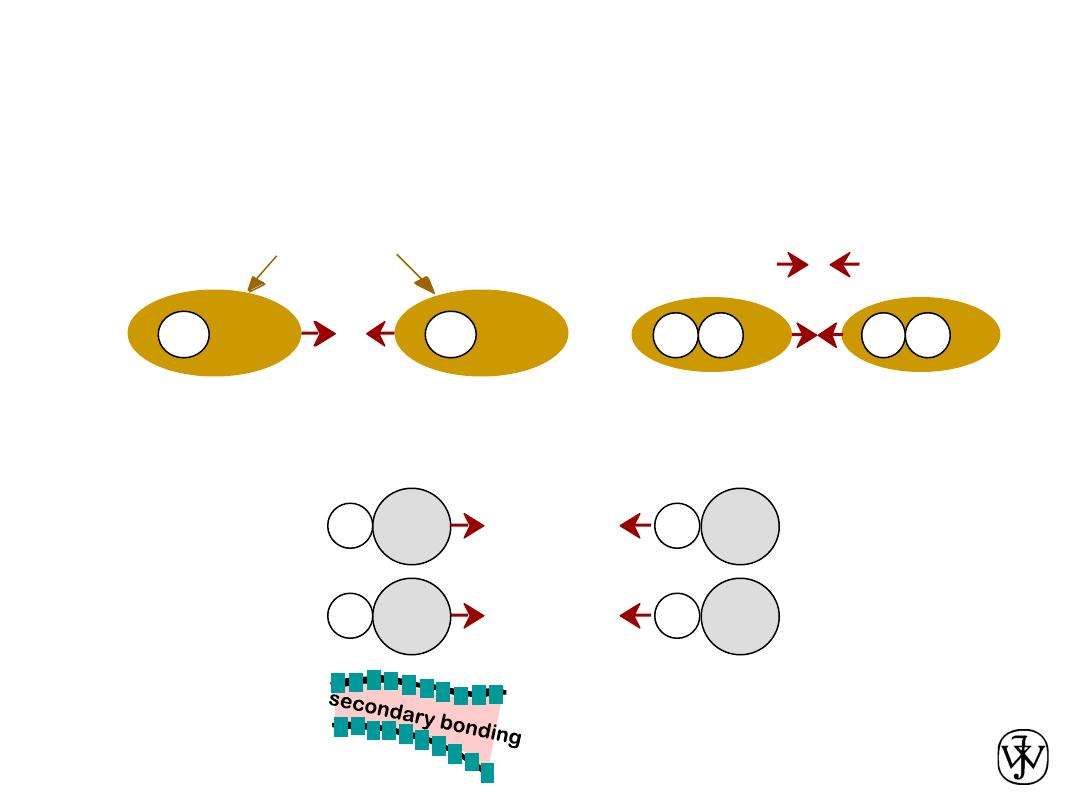

Arises from interaction between electric

dipoles

Secondary (

van der Waals

) bonds

• Dipoles fluctuating rapidly and interacting

asymmetric electron

clouds

+

-

+

-

H

H

H

H

H2

H2

e.g. liquid H

2

• Permanent

dipoles

-general case:

-ex: liquid HCl

-ex: polymer

H Cl

H Cl

+

-

+

-

Within an organic molecule the bonding is

mostly covalent, while between molecules

the bonding is mostly van der Waals.

Chapter 2 -

Hydrogen bonds

• Between hydrogen atoms and the nearby negative end of a

molecular dipole, to strongly electronegative atoms such as O or N.

• Partly covalent and partly electrostatic.

• Much stronger than van der Waals bonds.

• Determines the unusual properties of water liquid and solid.

• Also occurs with other molecules, and even between parts of

complex molecules such as proteins.

40

Chapter 2 -

Table 2.3.

Chapter 2 - 42

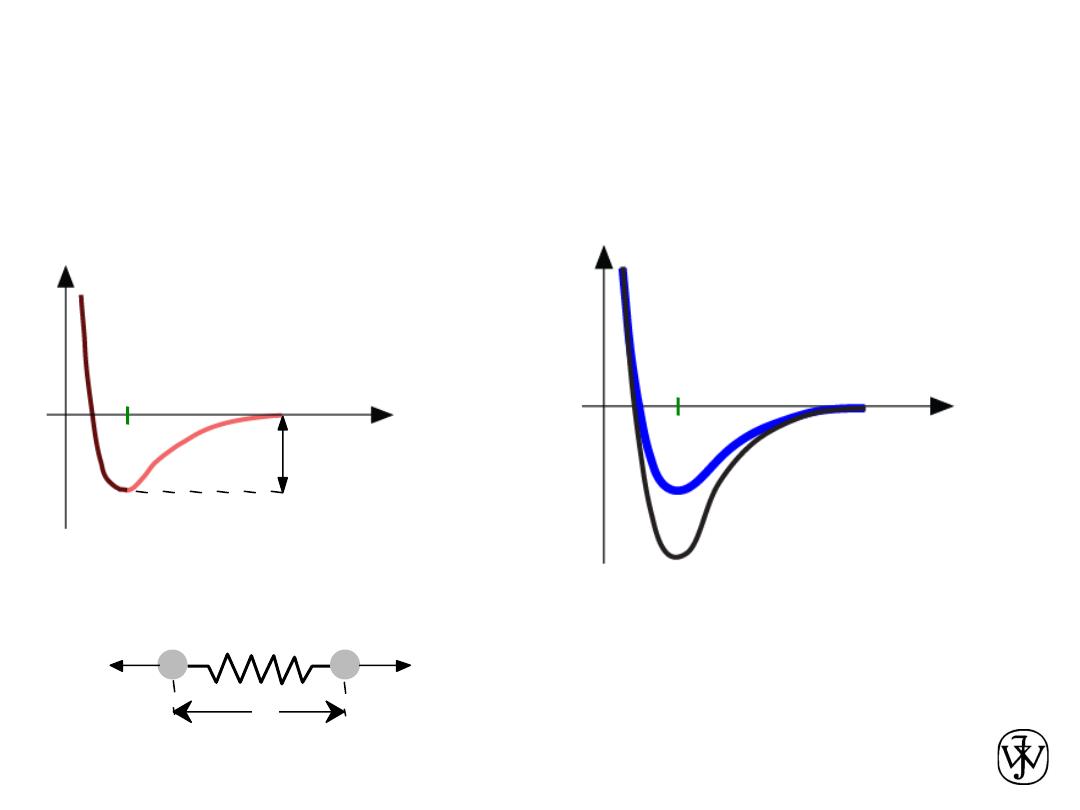

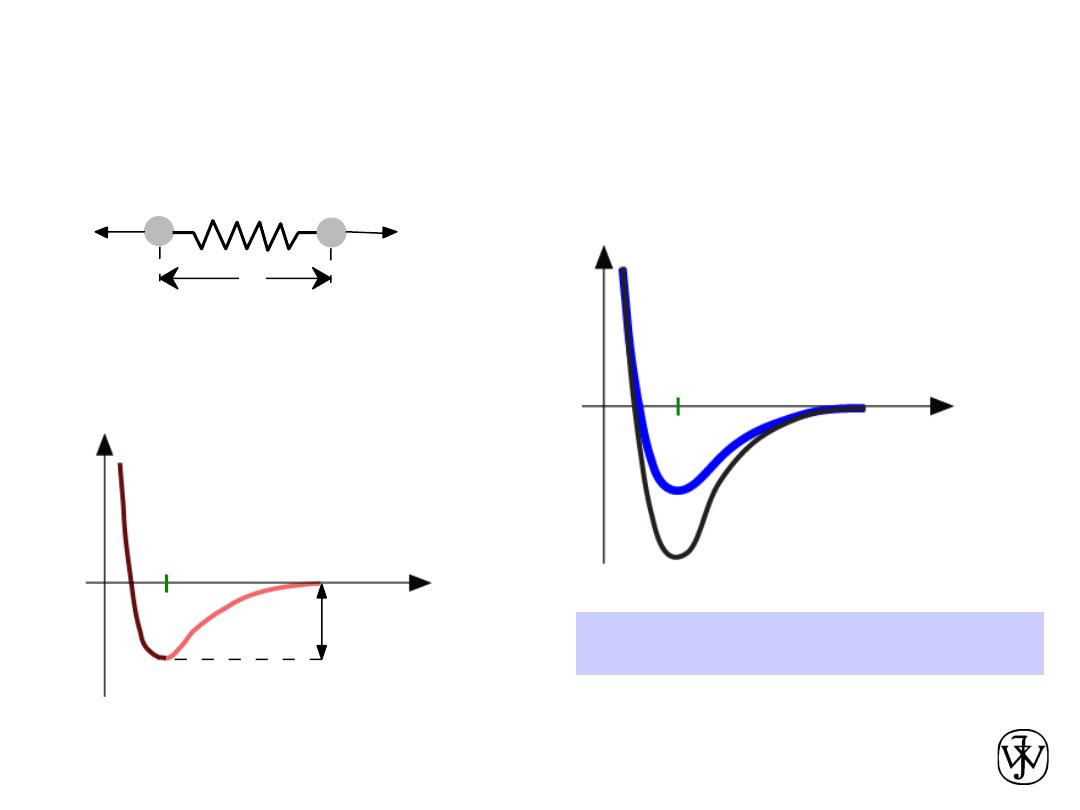

Interaction energy E

versus atomic separation r

Melting Temperature, T

m

T

m

is larger when E

o

is larger

Properties From Bonding: Melting point

Atomic separation r

r

r

o

r

Energy

larger T

m

smaller T

m

E

o

“

bond energy”

Energy

r

o

r

unstretched bond length

Chapter 2 - 43

Coefficient of thermal expansion,

a

a is larger when E

o

is smaller

Properties From Bonding: Thermal expansion

= a (

T

2

-

T

1

)

DL

Lo

coeff. thermal expansion

DL

length,

Lo

unheated, T1

heated, T2

r

o

r

smaller

a

larger

a

Energy

E

o

E

o

Chapter 2 - 44

• Occurs between + and - ions.

• Requires

electron transfer.

• Large difference in electronegativity required.

• Example: NaCl

Ionic Bonding

Na (metal)

unstable

Cl (nonmetal)

unstable

electron

+

-

Coulombic

Attraction

Na (cation)

stable

Cl (anion)

stable

Chapter 2 -

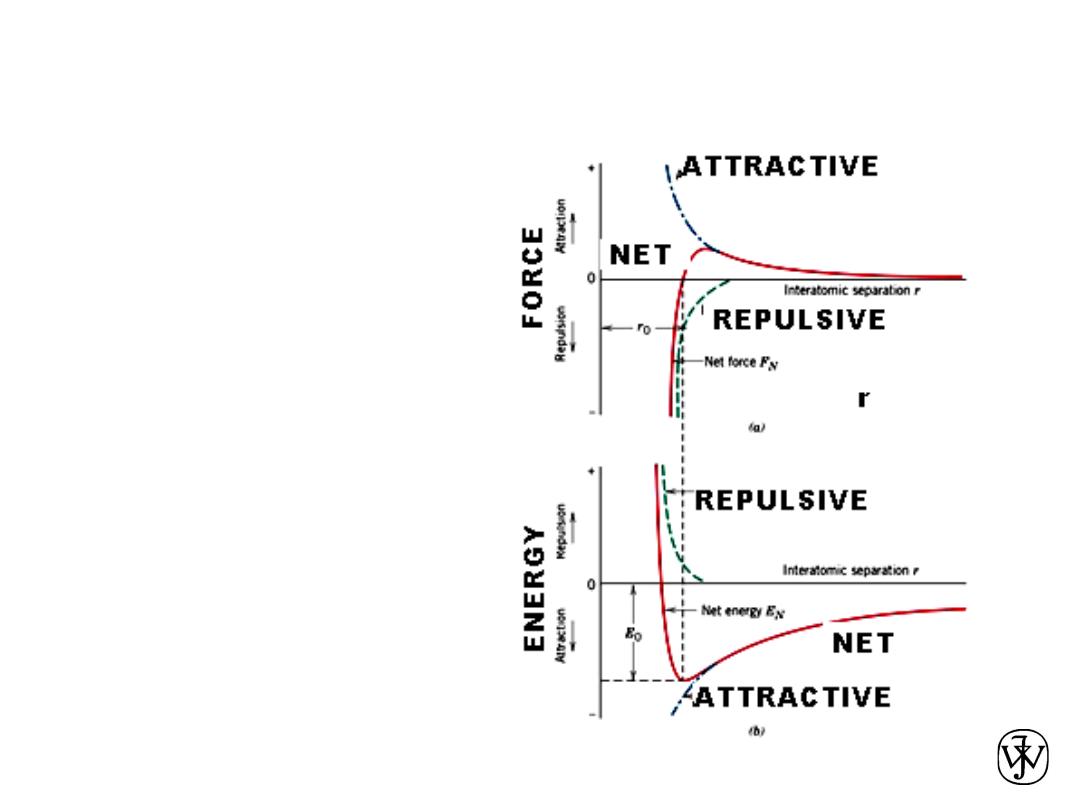

FORCES AND ENERGIES

45

(a) The

dependence of repulsive,

attractive, and net forces

on interatomic

separation for two

isolated atoms.

(b) The dependence of

repulsive, attractive, and

net potential energies on

interatomic separation

for two isolated atoms.

Chapter 2 - 46

Attractive force F

A

Repulsive force F

R

Net force F

N

Chapter 2 - 47

Chapter 2 -

Bonding Forces and Energies

48

2.13 Calculate the force of attraction

between a K

+

and an O

2-

ion the

centers of which are separated by a

distance of r0 =1.5 nm.

The attractive force between two ions

FA is just the derivative with respect to

the interatomic separation of the

attractive energy expression, Equation

2.8, which is just

Solution

Chapter 2 - 49

F

A

=

dE

A

dr

=

d

-

A

r

æ

è

ç

ö

ø

÷

dr

=

A

r

2

The constant A in this expression is

defined in footnote 3. Since the valences

of the K+ and

O2- ions

(Z1 and Z2) are +1 and -2, respectively,

Z1 = 1 and Z2 = 2, then

Chapter 2 - 50

F

A

=

(Z

1

e) (Z

2

e)

4pe

0

r

2

=

(1)(2)

(

1.602 ´ 10

-19

C

)

2

(4)(p) (8.85 ´ 10

-12

F/m) (1.5 ´ 10

-9

m)

2

=2.05

´

10^(-10 ) N

Chapter 2 -

IONIC FORCE / P 31 FOOT-NOTE

51

F= (Z1 *Z2 * e^2)/(4*π*ε

0

*r^2);;

e= 1.602 *10^(-19) COULOMBS ;;

ε

0

= 8.85 * 10^(-12 )

Z1, Z2 = VALENCIES OF IONS

Chapter 2 - 52

Ionic Bonding

• Energy – minimum energy most stable

– Energy balance of

attractive

and

repulsive

terms

Attractive energy E

A

Net energy E

N

Repulsive energy E

R

Interatomic separation r

r

A

n

r

B

E

N

=

E

A

+

E

R

=

+

-

Adapted from Fig. 2.8(b),

Callister & Rethwisch 8e.

Chapter 2 - 53

• Predominant bonding in

Ceramics

Adapted from Fig. 2.7, Callister & Rethwisch 8e. (Fig. 2.7 is adapted from Linus Pauling, The Nature of the

Chemical Bond, 3rd edition, Copyright 1939 and 1940, 3rd edition. Copyright 1960 by Cornell University.

Examples: Ionic Bonding

Give up electrons

Acquire electrons

NaCl

MgO

CaF2

CsCl

Chapter 2 - 54

C: has 4 valence e

-

,

needs 4 more

H: has 1 valence e

-

,

needs 1 more

Electronegativities

are comparable.

Adapted from Fig. 2.10, Callister & Rethwisch 8e.

Covalent Bonding

• similar

electronegativity

\ share electrons

• bonds determined by valence – s & p orbitals

dominate bonding

• Example: CH

4

shared electrons

from carbon atom

shared electrons

from hydrogen

atoms

H

H

H

H

C

CH4

Chapter 2 - 55

Primary Bonding

• Metallic Bond

-- delocalized as electron cloud

• Ionic-Covalent Mixed Bonding

% ionic character

=

where X

A

& X

B

are Pauling electronegativities

%)

100

(

x

1

- e

-

(X

A

-X

B

)

2

4

æ

è

ç

ç

ç

ö

ø

÷

÷

÷

ionic

73.4%

(100%)

x

e

1

character

ionic

%

4

)

2

.

1

5

.

3

(

2

=

÷÷

÷

ø

ö

çç

ç

è

æ

-

=

-

-

Ex: MgO

X

Mg

= 1.2

X

O

= 3.5

Chapter 2 -

METALLIC BONDING

56

Chapter 2 - 57

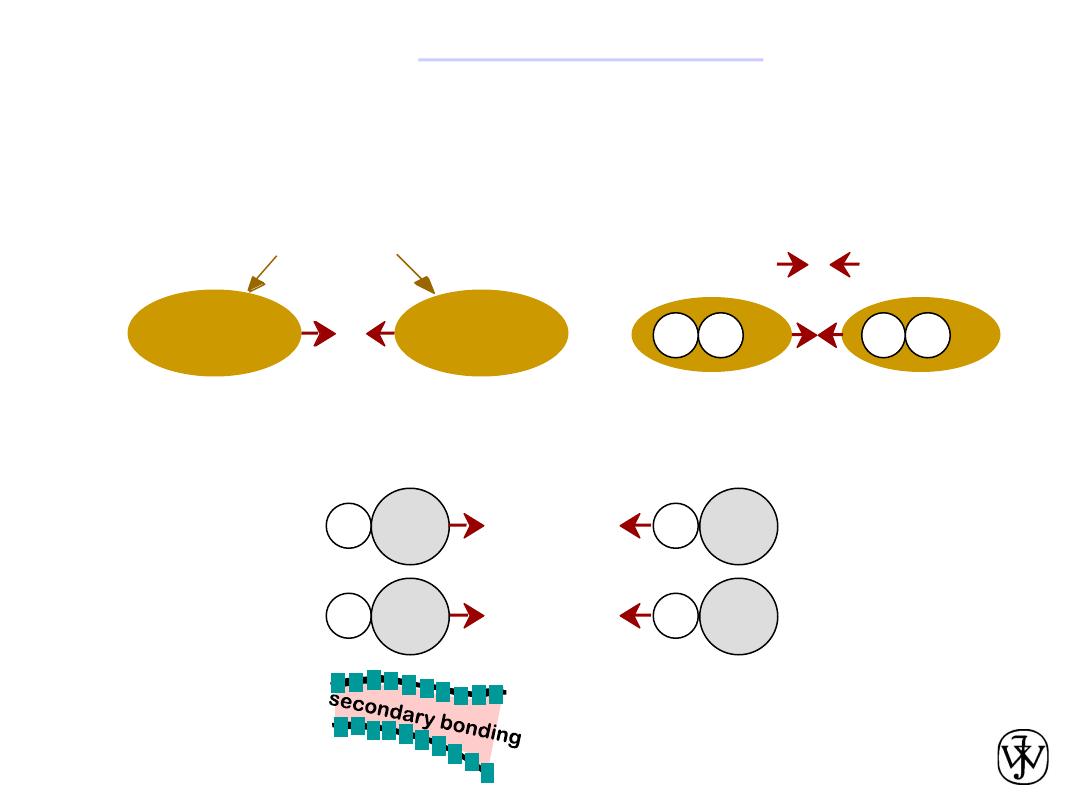

Arises from interaction between

dipoles

• Permanent

dipoles

-molecule induced

• Fluctuating

dipoles

-general case:

-ex: liquid HCl

-ex: polymer

Adapted from Fig. 2.13,

Callister & Rethwisch 8e.

Adapted from Fig. 2.15,

Callister & Rethwisch 8e.

SECONDARY BONDING

asymmetric electron

clouds

+

-

+

-

secondary

bonding

H

H

H

H

H2

H2

secondary

bonding

ex: liquid H2

H Cl

H Cl

secondary

bonding

secondary

bonding

+

-

+

-

secondary bonding

Chapter 2 - 58

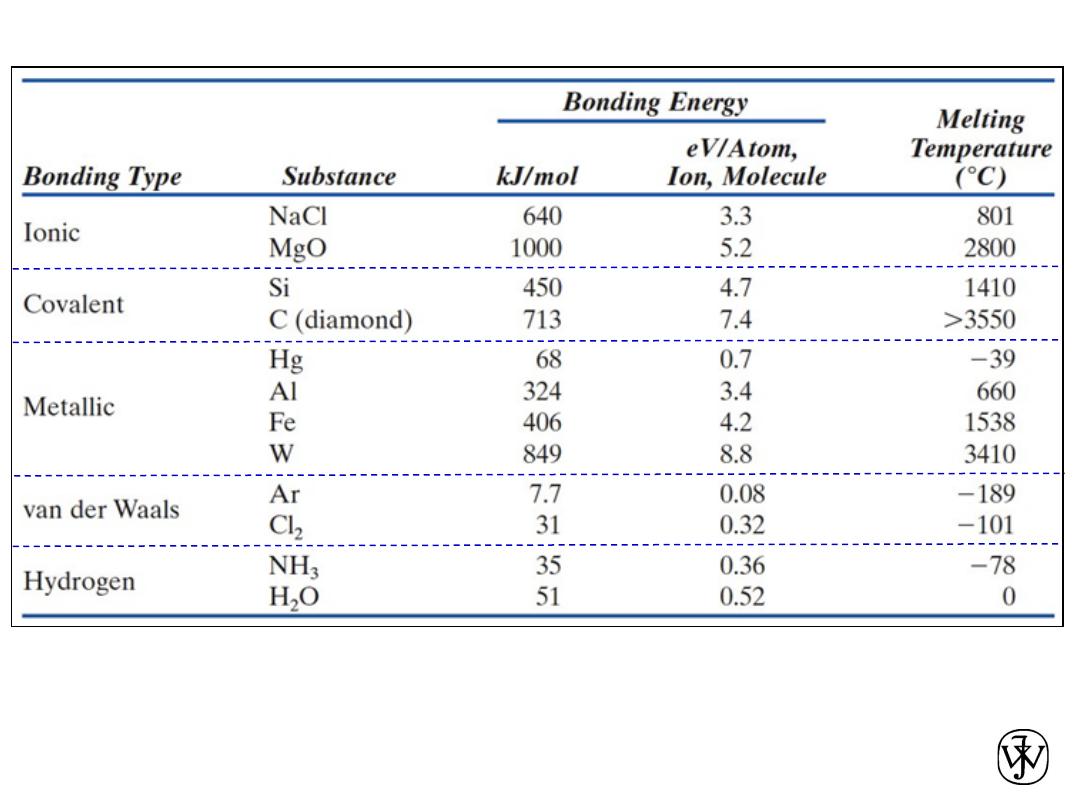

Type

Ionic

Covalent

Metallic

Secondary

Bond Energy

Large!

Variable

large-Diamond

small-Bismuth

Variable

large-Tungsten

small-Mercury

smallest

Comments

Nondirectional (

ceramics

)

Directional

(

semiconductors

,

ceramics

polymer

chains)

Nondirectional (

metals

)

Directional

inter-chain (

polymer

)

inter-molecular

Summary: Bonding

Chapter 2 - 59

•

Bond length

, r

•

Bond energy

, E

o

•

Melting Temperature

, T

m

T

m

is larger if E

o

is larger.

Properties From Bonding: T

m

r

o

r

Energy

r

larger T

m

smaller T

m

E

o

=

“bond energy”

Energy

r

o

r

unstretched length

Chapter 2 - 60

•

Coefficient of thermal expansion

,

a

•

a ~ symmetric at r

o

a is larger if E

o

is smaller.

Properties From Bonding :

a

= a (

T

2

-

T

1

)

DL

Lo

coeff. thermal expansion

DL

length,

L

o

unheated, T1

heated, T2

r

o

r

smaller

a

larger

a

Energy

unstretched length

E

o

E

o

Chapter 2 - 61

Ceramics

(Ionic & covalent bonding):

Large bond energy

large T

m

large E

small

a

Metals

(Metallic bonding):

Variable bond energy

moderate T

m

moderate E

moderate

a

Summary: Primary Bonds

Polymers

(Covalent & Secondary):

Directional Properties

Secondary bonding dominates

small T

m

small E

large

a