CHAPTER 11: METAL ALLOYS

APPLICATIONS AND PROCESSING

ISSUES TO ADDRESS...

• How are metal alloys classified and how are they used?

• What are some of the common fabrication techniques?

• How do properties vary throughout a piece of

material

that has been quenched, for example?

• How can properties be modified by post heat treatment?

Often a materials problem is really one of selecting the material that has the

right combination of characteristics for a specific application. Therefore, the

people who are involved in the decision making should have some

knowledge of the available options.

Materials selection decisions may also be influenced by the ease with which

metal alloys may be formed or manufactured into useful components. Alloy

properties are altered by fabrication processes, and, in addition, further

property alterations may be induced by the employment of appropriate

heat treatments.

Metal alloys, by virtue of composition, are often grouped into two classes—

ferrous and nonferrous. Ferrous alloys, those in which iron is the principal

constituent, include steels and cast irons. The nonferrous ones—all alloys

that are not iron based.

5/3/17

Classifications of Metal Alloys

Metal Alloys

Ferrous

Nonferrous

Steels

Steels

1

<1.4wt%C

.4wt%C

C

Cast

ast

Irons

Irons

3-4.5wt%C

Cu Al Mg Ti

Some definitions:

<

3-4.5tic

•

•

Ferrous alloys: iron is the prime constituent

Ferrous alloys are relatively inexpensive and

extremely versatile

T(

°C)

1600

d

L

• Thus these alloys are wide spread engineering

1400

g+L

materials

Alloys that are so brittle that forming by

deformation is not possible ordinary are cast

g

1200

1000

L+Fe C

3

4.30

Eutectic

1148

°C

•

austenite

Fe C

3

cementite

• Alloys that are amenable to mechanical

deformation are termed wrought

g+Fe C

3

a

800

727

°C

ferrite

0.77

Eutectoid

a

+Fe C

3

• Heat-treatable - are alloys whose mechanical

6 00

strength can be improved by heat-treatment

4 000

(Fe)

(e.g. precipitation hardening or martensitic

transformations).

1

2

3

4

5

6

6.7

Carbon concentration, wt.% C

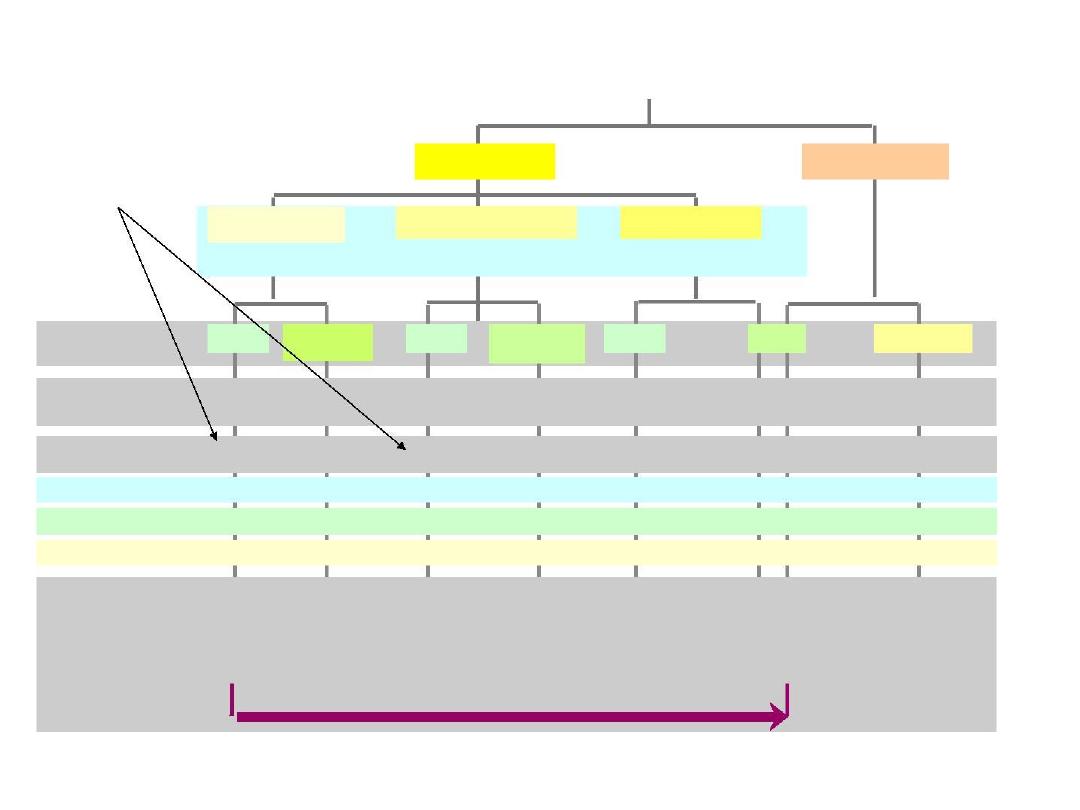

Classification of Steels

10-plane

or 0.4 C wt.%

Low Alloy

High Alloy

0.1

Medium-carbon High carbon

Low carbon

<0.25wt%C

0.25-0.6wt%C

0.6-1.4wt%C

High

Heat

Name:

Plain strength

Plain

Plain

Tool

Stainless

treatable

Additions:

noneCu,V,Ni,Mo none Cr, Ni,Mo none

Cr, V,Mo,W

Cr, Ni, Mo

Example

(ASTM#):1010

A633

1040

4340

1095

4190

304

Hardenability

TS

0

-

+

0

+

+

++

++

++

+

+++

++

0

0

EL

+

+

0

-

-

--

++

wear

applications

high T

applications

turbines

furnaces

corrosion

resistant

Applications:

auto

struc. towers

sheet press.

bridges crank

shafts

bolts

pistons

gears

wear

drills

saws

dies

vessels hammers applications

blades

increasing strength, cost, decreasing ductility

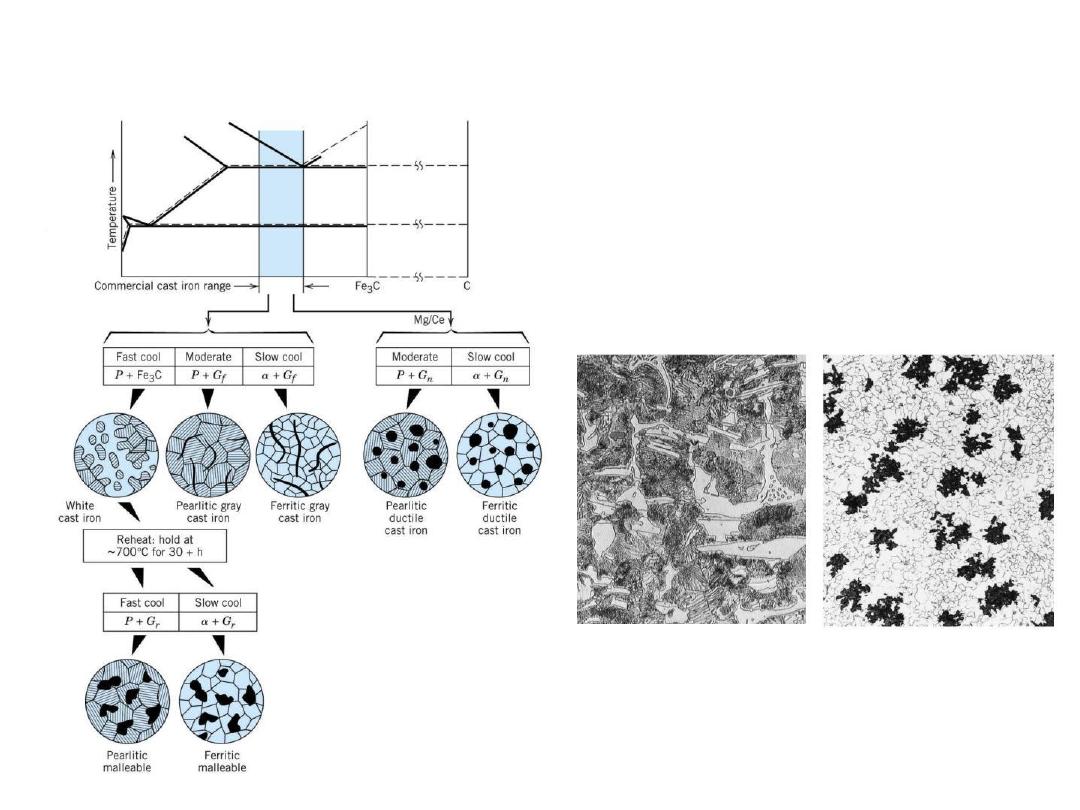

CAST IRON

• The cast irons are the ferrous alloys with greater that 2.14 wt. % carbon, but

typically contain 3-4.5 wt. % of C as well as other alloying elements, such as

silicon (~3 wt..%) which controls kinetics of carbide formation

3-4.5wt%C

3-4.5wt%C

•

(1150-1300

°C),

These alloys have relatively low melting points

do not formed undesirable surface

T(

°C)

1600

d

films when poured, and undergo moderate shrinkage

during solidification. Thus can be easily melted and

amenable to casting

L

1400

g+L

g

1200

1000

L+Fe C

3

1148

°C

austenite

•

There are four general types of cast irons:

4.30

Eutectic

1.

cementite

fracture surface. Large amount of Fe C are formed

during casting, giving hard brittle material

White iron has a characteristics white, crystalline

Fe C

3

g+Fe C

3

727

°C

3

0.77

Eutectoid

a

+Fe C

3

6 00

Carbon concentration, wt.% C

2. Gray iron has a gray fracture surface with finely

4000

(Fe)

faced structure. A large Si content (2-3 wt. %)

1

2

3

4

5

6

6.7

promotes C flakes precipitation rather than carbide

Ductile iron: small addition (0.05 wt..%) of Mg to gray iron changes the flake C

microstructure to spheroidal that increases (by factor ~20) steel ductility

Malleable iron: traditional form of cast iron with reasonable ductility. First cast to

white iron and then heat-treated to produce nodular graphite precipitates.

3.

4.

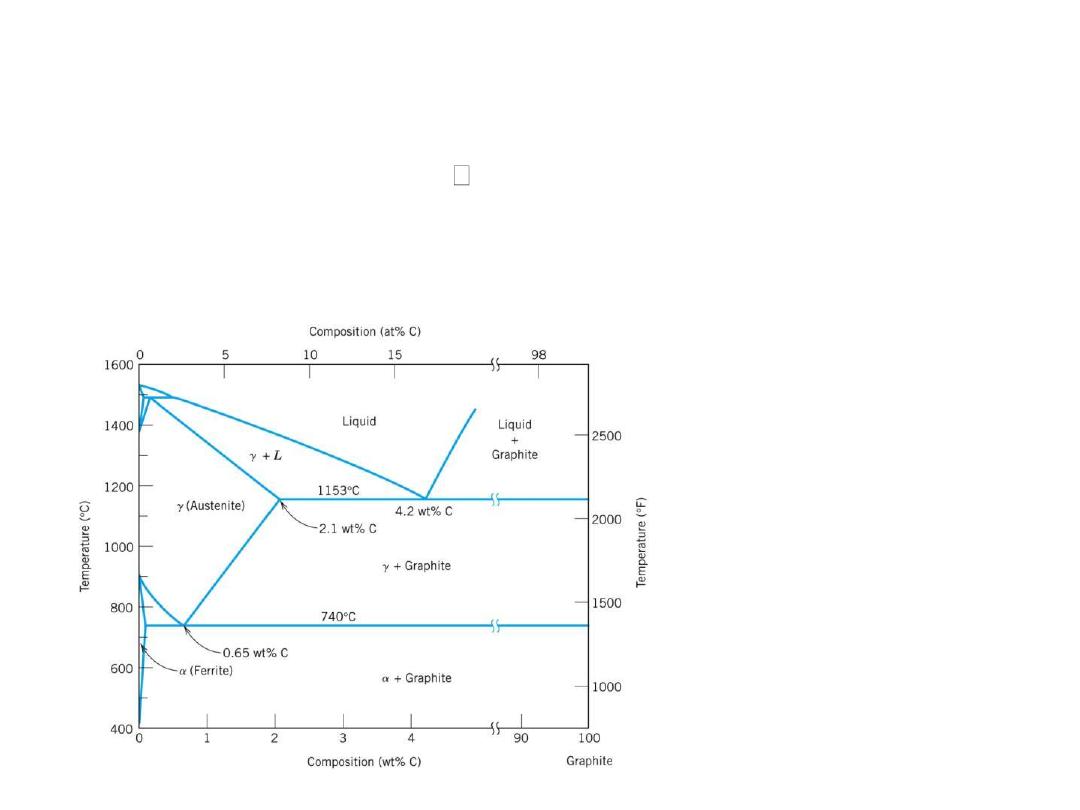

Equilibrium and Metastable Phases

• Cementite (Fe C) is a metastable phase and after long term treatment

decompose to form a-ferrite and carbon:

3

Fe3C 3Fe(S) + C(graphite)

•

•

Slow cooling and addition of some elements (e.g. Si) promote graphite formation

Properties of cast irons are defined by the amount and microstructure of

existing carbon phase.

•Equilibrium iron-carbon

phase diagram

White and Malleable Cast Irons

• The low-silicon cast irons (<1.0wt.%),

produced under rapid cooling conditions

•

•

•

Microstructure: most of cementite

Properties: extremely hard very but brittle

White iron is an intermediate for the

production of malleable iron

White iron:

Malleable iron:

light Fe C regions dark graphite rosettes

3

surrounded

by pearlite

in a-Fe matrix

Gray and Ductile Cast Irons

The gray irons contain 1-31.0 wt..% of Si

•

•

•

Microstructure: flake

–shape graphite in ferrite matrix

Properties: relatively weak and brittle in tension BUT very effective in damping

vibrational energy an high resistive to wear!!

•Ductile (or Nodular) iron :

small addition of Mg or/and Ce to the

gray iron composition before casting

•

Microstructure: Nodular or spherical-like

graphite structure in pearlite or ferric matrix

Properties: Significant increase in material

ductility !!

Applications: valves, pump bodies, gears

and other auto and machine components.

•

•

Gray iron:

Dark graphite flakes

In a-Fe matrix

Ductile iron:

dark graphite nodules

in a-Fe matrix

RAPIDLY SOLIDIFIED FERROUS ALLOYS

• Eutectic compositions that permit cooling to a glass transition

temperature at practically reachable quench rate (10

5

and 10

6

C

°/s) –

- rapidly solidified alloys

•

•

Boron, B, rather than carbon is a primary alloying element for

amorphous ferrous alloys

Properties:

(a) absence of grain boundaries

– easy magnetized materials

(b) extremely fine structure

– exceptional strength and toughness

Compositions (wt. %)

•Some Amorphous

Ferrous Alloys

B

Si

Cr

Ni Mo

P

20

10

28

6

10

6

6

40

14

NONFERROUS ALLOYS

• Cu Alloys

• Al Alloys

Brass

: Zn is prime impurity

(costume jewelry, coins,

corrosion resistant)

r: 2.7g/cm

3

-lower

-Cu, Mg, Si, Mn, Zn additions

-solid solutions or precipitation

strengthened (structural

aircraft parts

Bronze

: Sn, Al, Si, Ni are

prime impurities

(bushings, landing gear)

& packaging)

Nonferrous

• Mg Alloys

Cu-Be

precipitation-hardened

-very low r: 1.7g/cm

3

-ignites easily

Alloys

for strength

- aircraft, missiles

• Ti Alloys

• Refractory metals

-lower r: 4.5g/cm

3

vs 7.9 for steel

• Noble metals

-high melting T

-Nb, Mo, W, Ta

-reactive at high T

-Ag, Au, Pt

-space applications

- oxidation/corrosion

resistant

Cooper and its Alloys

• Cooper: soft and ductile; unlimited cold-work capacity, but difficult to

machine.

•

•

Cold-working and solid solution alloying

Main types of Copper Alloys:

–

–

–

Brasses: zinc (Zn) is main substitutional impurity; applications: cartridges,

auto-radiator. Musical instruments, coins

Bronzes: tin (Sn), aluminum (Al), Silicon (Si) and nickel (Ni); stronger

than brasses with high degree of corrosion resistance

Heat-treated (precipitation hardening) Cu-alloys: beryllium coopers;

relatively high strength, excellent electrical and corrosion properties BUT

expensive; applications: jet aircraft landing gear bearing, surgical and

dental instruments.

•

Copper

’s advantages as primary

metal and recycled metal, for brazed,

long-life radiators and radiator parts

for cars and trucks:

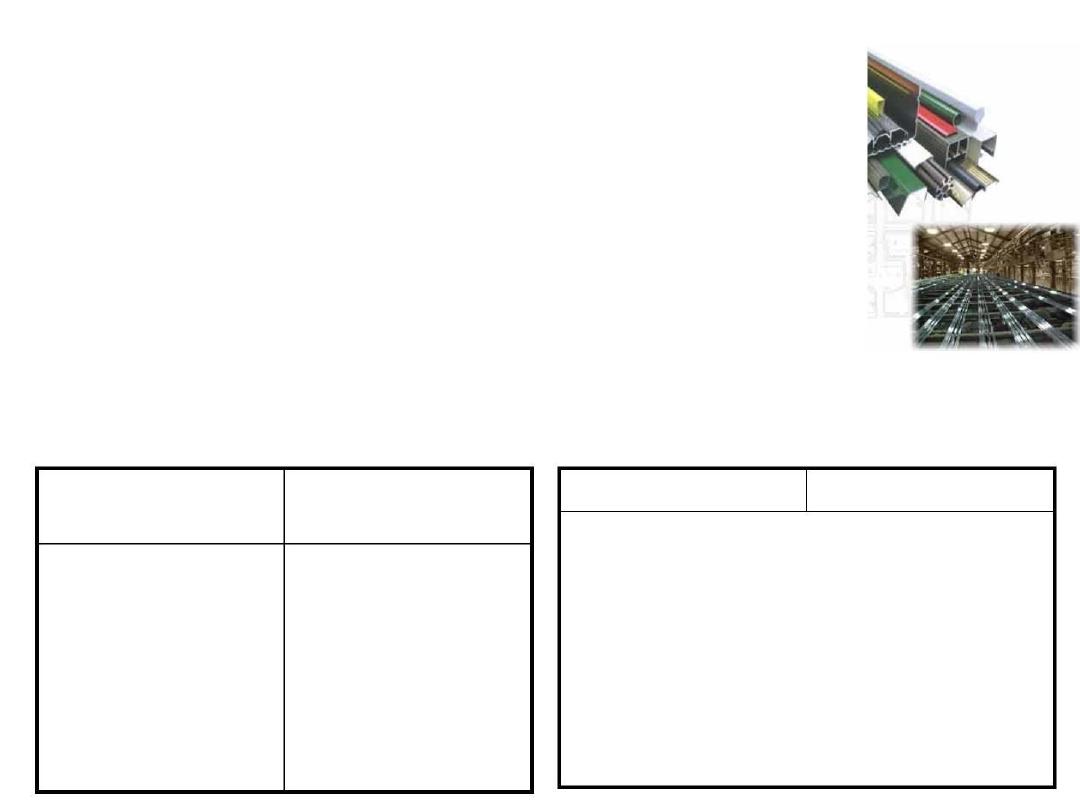

Aluminum and its Alloys

•

•

Low density (~2.7 g/cm ), high ductility (even at room temperature),

3

high electrical and thermal conductivity and resistance to corrosion

BUT law melting point (~660

°C)

Main types of Aluminum Alloys:

-

-

-

Wrought Alloys

Cast Alloys

Others: e.g. Aluminum-Lithium Alloys

• Applications: form food/chemical handling to aircraft structural parts

Typical alloying elements and alloy

Temper designation systems for

designation systems for Aluminum Alloys

Aluminum Alloys

Numerals

Major Alloying

Element(s)

Temper

Definition

F

As fabricated

Annealed

O

1XXX

2XXX

3XXX

4XXX

5XXX

6XXX

7XXX

8XXX

None (>99.00 %Al)

H1

H2

H3

T1

T2

T3

T4

T5

T6

T7

T8

T9

Strain-hardened only

Strain-hardened and partially annealed

Strain-hardened and stabilized

Cu

Cooled from elevated-T shaping and aged

Cooled from elevated-T shaping, cold-work, aged

Solution heat-treat., cold-work, naturally aged

Solution heat-treat and naturally aged

Mn

Si

Mg

Cooled from elevated-T shaping, artificially aged

Solution heat-treat. and artificially aged

Solution heat-treat and stabilized

Mg an Si

Zn

Solution heat-treat, cold-work, artificially aged

Solution heat-treat, artificially aged, cold-work

Other elements (e.g. Li)

Magnesium and its Alloys

Formula 1

Gearbox Casting

• Key Properties:

• Light weight

·

·

·

Low density (1.74 g/cm two thirds that of aluminium)

3

Good high temperature mechanical properties

Good to excellent corrosion resistance

•

•

Very high strength-to density ratios (specific strength)

In contrast with Al alloys that have fcc structure with (12 ) slip systems and thus high

ductility, hcp structure of Mg with only three slip systems leads to its brittleness.

• Applications: from tennis rockets to aircraft and missiles

Example: Aerospace

RZ5 (Zn 3.5 - 5,0 SE 0.8 - 1,7 Zr 0.4 - 1,0 Mg remainder), MSR (AG 2.0 - 3,0 SE 1.8 -

2,5Zr 0.4 - 1,0 Mg remainder) alloys are widely used for aircraft engine and gearbox

casings. Very large magnesium castings can be made, such as intermediate compressor

casings for turbine engines. These include the Rolls Royce Tay casing in MSR, which

weighs 130kg and the BMW Rolls Royce BR710 casing in RZ5. Other aerospace

applications include auxiliary gearboxes (F16, Euro-fighter 2000, Tornado) in MSR or

RZ5, generator housings (A320 Airbus, Tornado and Concorde in MSR) and canopies,

generally in RZ5.

Titanium and its Alloys (1)

•

•

Titanium and its alloys have proven to be

technically superior and cost-effective materials of

construction for a wide variety of aerospace,

industrial, marine and commercial applications.

The properties and characteristics of titanium which

are important to design engineers in a broad

spectrum of industries are:

- Excellent Corrosion Resistance:

Titanium is

immune to corrosive attack by salt water or marine

atmospheres. It also exhibits exceptional resistance

to a broad range of acids, alkalis, natural waters and

industrial chemicals.

-

Superior Erosion Resistance:

Titanium offers

superior resistance to erosion, cavitation or

impingement attack. Titanium is at least twenty

times more erosion resistant than the copper-nickel

alloys.

-

High Heat Transfer Efficiency:

Under "in

service" conditions, the heat transfer properties of

titanium approximate those of admiralty brass and

copper-nickel.

Other Alloys

• The Refractory Metals: Nb (m.p.=2468

°C); Mo (°C); W (°C); Ta(3410°C)

-

-

Also: large elastic modulus, strength, hardness in wide range of temperatures

Applications:

• The Super alloys – possess the superlative combination of properties

-

-

Examples:

Applications: aircraft turbines; nuclear reactors, petrochemical equipment

• The Noble Metal Alloys:

Ru(44), Rh (45), Pd (46), Ag (47), Os (75), Ir (77), Pt (78), Au (79)

- expensive are notable in properties: soft, ductile, oxidation resistant

Applications: jewelry (Ag, Au, Pt), catalyst (Pt, Pd, Ru),

-

thermocouples (Pt, Ru), dental materials etc.

• Miscellaneous Nonferrous Alloys:

-

65Ni/28Cu/7wt%Fe

Nickel and its alloy: high corrosion resistant (Example: monel

–

– pumps valves in aggressive environment)

Lead, tin and their alloys: soft, low recrystallization temperature, corrosion

resistant (Applications: solders, x-ray shields, protecting coatings)

-

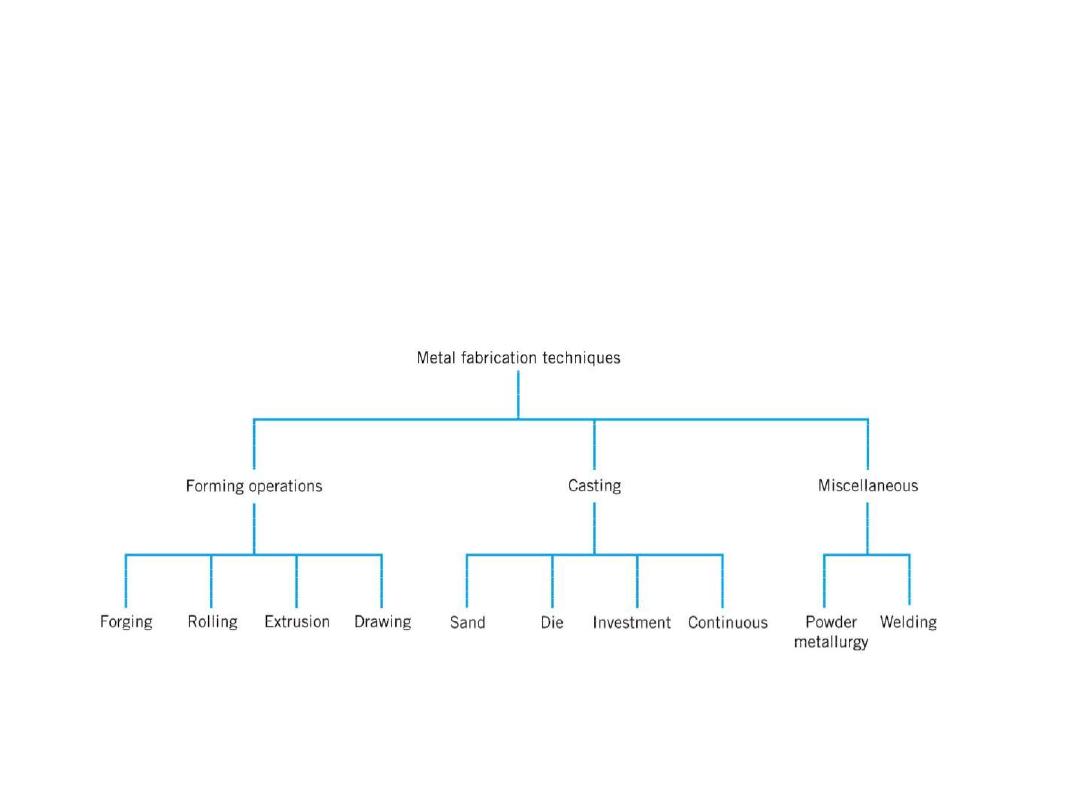

Fabrication of Metals

• Fabrication methods chosen depend on:

-

-

-

properties of metal

size and shape of final piece

cost

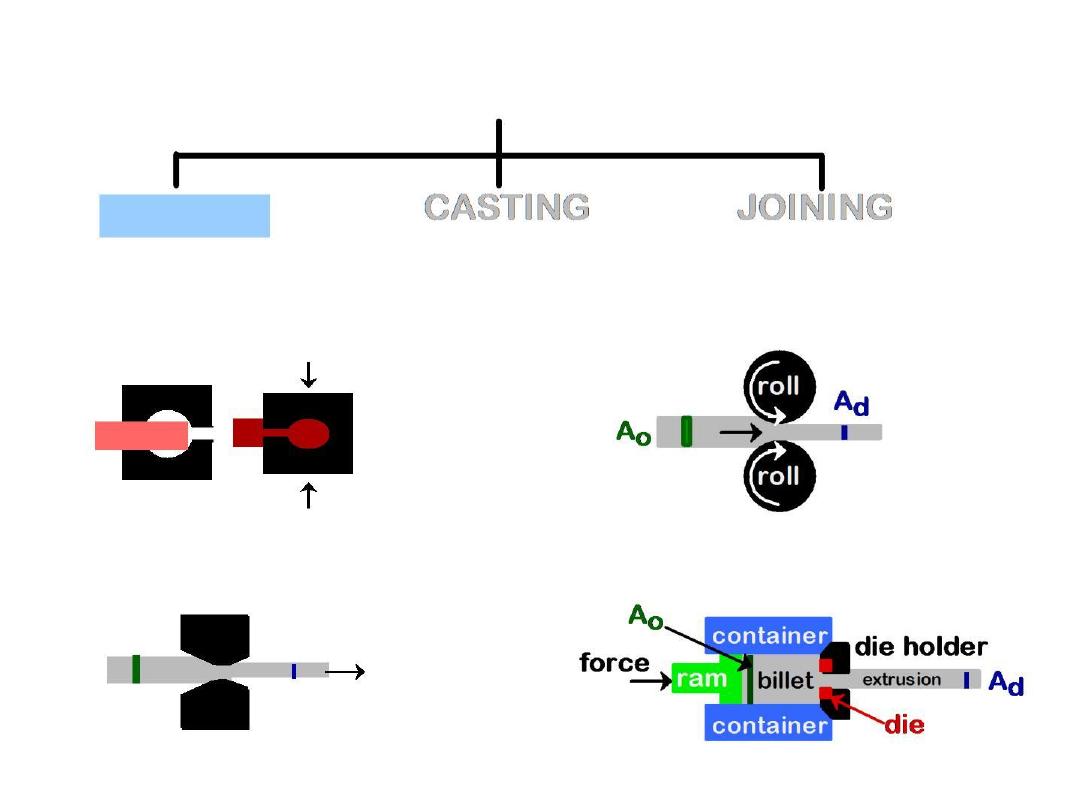

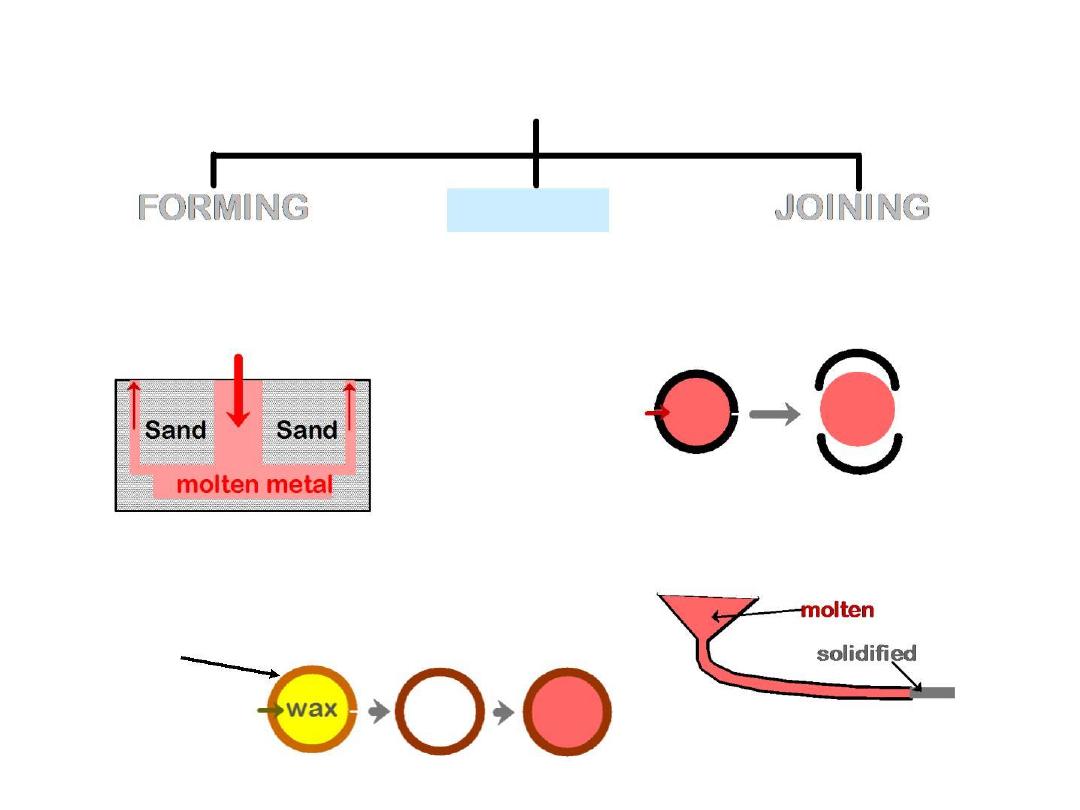

METAL FABRICATION METHODS-I

FORMING

•

Forging

(wrenches, crankshafts)

•

Rolling

(I-beams, rails)

force

die

A

blank

often at

Ad

elev. T

o

force

•

Drawing

•

Extrusion

(rods, wire, tubing)

(rods, tubing)

die

Ad

tensile

force

Ao

die

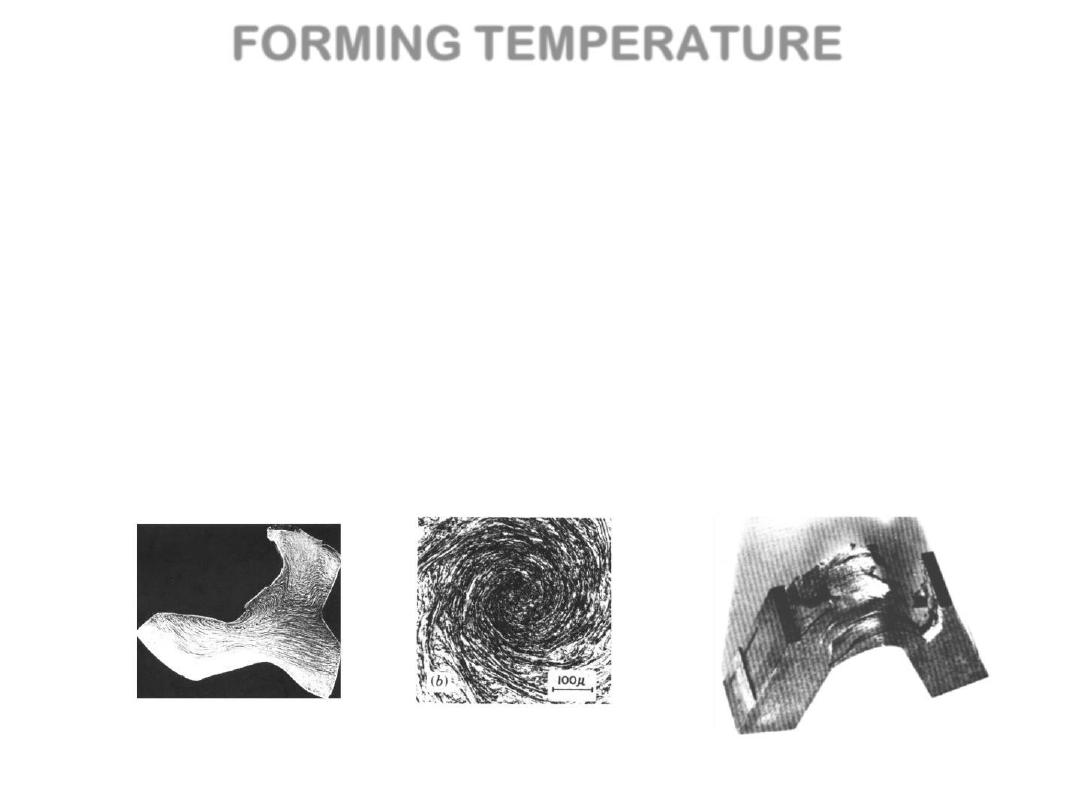

FORMING TEMPERATURE

•

Hot working: deformation

at T > T(recrystallization)

•

Cold working: deformation

at T < T (recrystallization)

+ higher quality surface

+ better mechanical properties

+ closer dimension control

+

+

-

less energy to deform

large repeatable deform.

surface oxidation: poor finish

- expensive and inconvenient

•

Cold worked microstructures

--generally are very

anisotropic!

--Forged

--Swaged

--Fracture resistant!

Extrusion and Rolling

•

•

The advantages of extrusion over rolling are as

follows:

- Pieces having more complicated cross-sectional

geometries may be formed.

- Seamless tubing may be produced.

The disadvantages of extrusion over rolling are as

follows:

- Nonuniform deformation over the cross-section.

- A variation in properties may result over the

cross-section of an extruded piece.

METAL FABRICATION METHODS-II

CASTING

•

Sand Casting

(large parts, e.g.,

auto engine blocks)

•

Die Casting

(high volume, low T alloys)

•

Continuous Casting

(simple slab shapes)

•

Investment Casting

(low volume, complex shapes

e.g., jewelry, turbine blades)

plaster

die formed

around wax

prototype

Casting

• The situations in which casting is the preferred fabrication technique are:

-

-

-

-

For large pieces and/or complicated shapes.

When mechanical strength is not an important consideration.

For alloys having low ductility.

When it is the most economical fabrication technique.

Different casting techniques:

Sand casting: a two-piece mold made of send is used, the surface finish is not an

important consideration, casting rates are low, and large pieces are usually cast.

Die casting: a permanent two-piece mold is used, casting rates are high, the molten

metal is forced into the mold under pressure, and small pieces are normally cast.

Investment casting: a single-piece mold is used, which is not reusable; it results in

•

•

•

high dimensional accuracy, good reproduction of detail, a fine surface finish; casting

rates are low.

• Continuous casting: at the conclusion of the extraction process, the molten metal

is cast into a continuous strand having either a rectangular or circular cross-section;

these shapes are desirable for secondary metal-forming operations. The chemical

composition and mechanical properties are uniform throughout the cross-section.

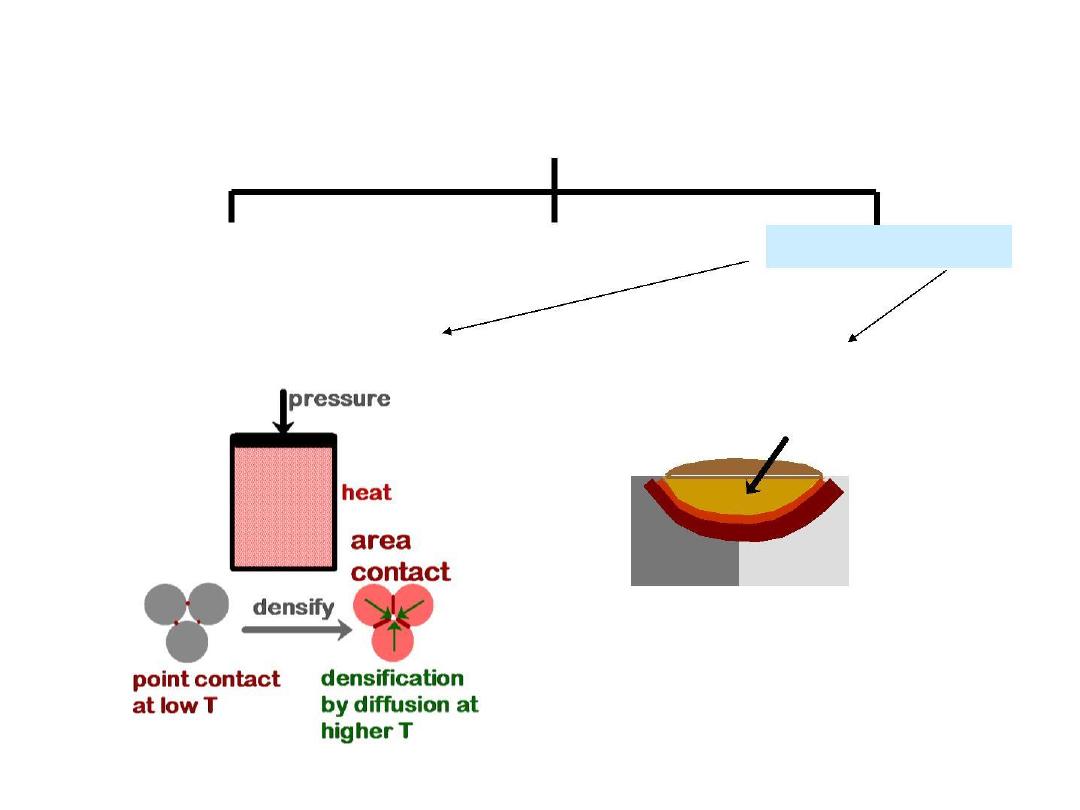

METAL FABRICATION METHODS-III

FORMING

CASTING

Miscellaneous

•

Powder Processing

•

Joining: Welding, brazing, soldering

filler metal (melted)

base metal (melted)

fused base metal

heat affected zone

unaffected

unaffected

piece 1

piece 2

•

Heat affected zone:

(region in which the

microstructure has been

changed).

Powder Processing

•

•

Some of the advantages of powder metallurgy over casting are as follows:

-

-

-

It is used for materials having high melting temperatures.

Better dimensional tolerances result.

Porosity may be introduced, the degree of which may be controlled (which is

desirable in some applications such as self-lubricating bearings).

Some of the disadvantages of powder metallurgy over casting are as follows:

-

-

Production of the powder is expensive.

Heat treatment after compaction is necessary.

Annealing

Process: heat alloy to T , for extended period of time then cool slowly.

Anneal

Goals: (1) relieve stresses; (2) increase ductility and toughness; (3) produce

specific microstructure

•

Spheroidize

(steels):

•

Stress Relief :

Make very soft steels

for good machining.

To reduce stress caused by:

-plastic deformation

-non-uniform cooling

-phase transform.

Heat just below T

E

& hold for 15-25h.

Types

of

•

Make soft steels for

Full Anneal

(steels):

Annealing

good forming by heating

to get , then cool in

• Process Anneal:

g

furnace to get coarse P.

To eliminate negate

e ffect of cold

working

by recovery/recrystallization

•

Normalize

(steels):

Deformed steel with large grains

heat-treated to make grains small.

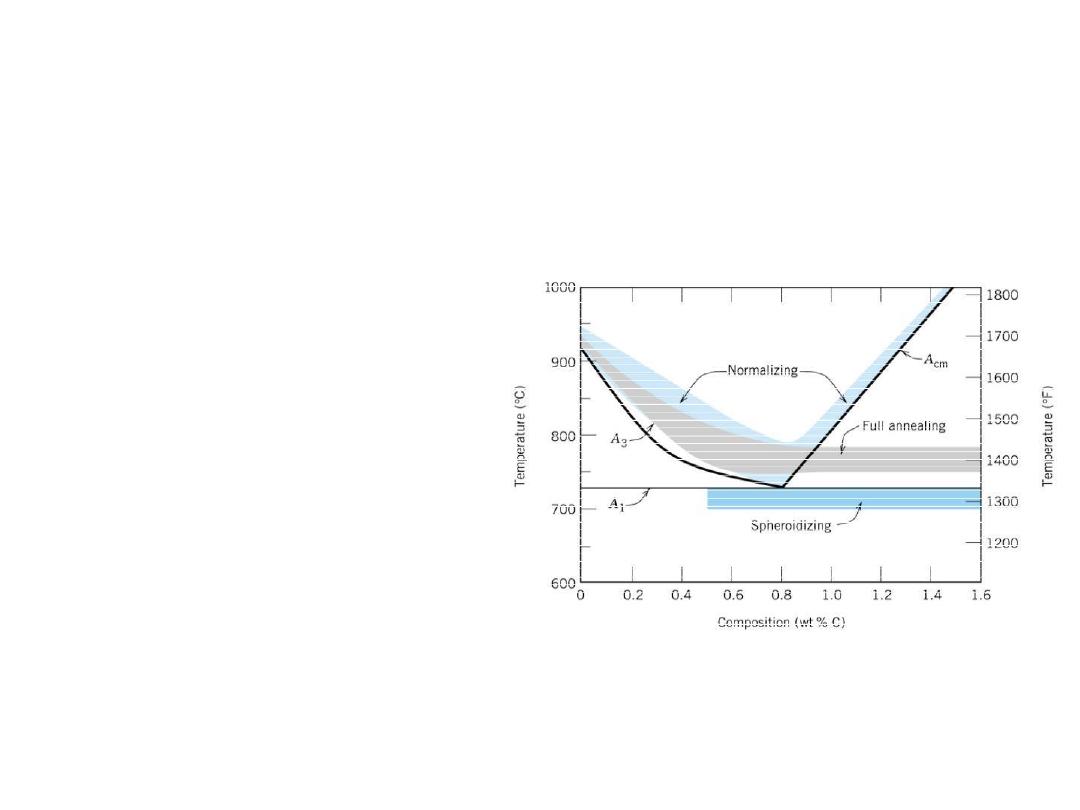

Thermal Processing of Metals: Steels

• Full annealing:

Heat to between 15 and 40

°C above the A3 line (if the concentration of carbon is less than the

eutectoid) or above the A1 line (if the concentration of carbon is greater than the eutectoid)

until the alloy comes to equilibrium; then furnace cool to room temperature.

The final microstructure is coarse pearlite.

•

Normalizing:

Heat to between 55 and 85

°C above the

upper critical temperature until the

specimen has fully transformed to

austenite, then cool in air. The final

microstructure is fine pearlite.

• Quenching:

Heat to a temperature within the austenite

phase region and allow the specimen to

fully austenite, then quench to room

temperature in oil or water. The final

microstructure is martensite.

• Tempering:

Heat a quenched (martensitic) specimen, to a temperature between 450 and 650

°C, for the time

necessary to achieve the desired hardness. The final microstructure is tempered martensite.

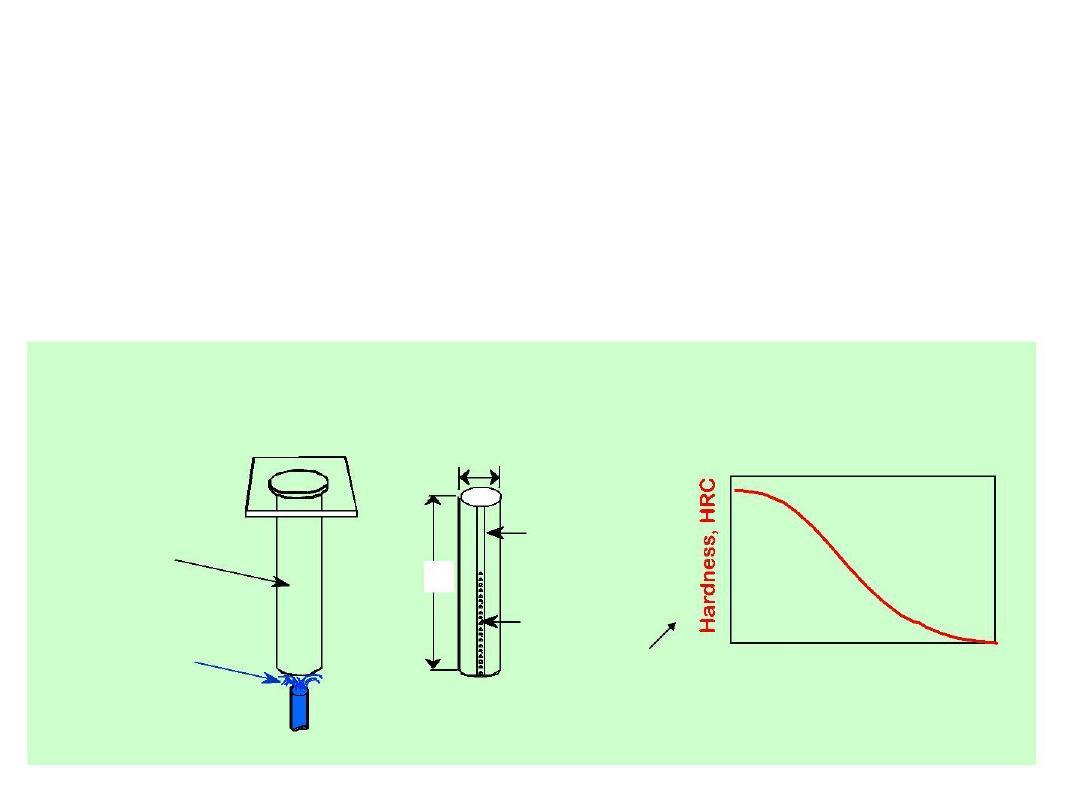

HARDENABILITY: STEELS

•

•

•

Full annealing and Spheroidizing: to produce softer steel for good

machining and forming

Normalization: to produce more uniform fine structure that tougher

than coarse-grained one

Quenching: to produce harder alloy by forming martensitic structure

Hardness versus

distance

from the quenched end

Jominy end-quenching test

1

”

flat ground

specimen

(heated to

4”

g-phase field)

Rockwell

Hardness test

Distance from

quenched end

24

°C water

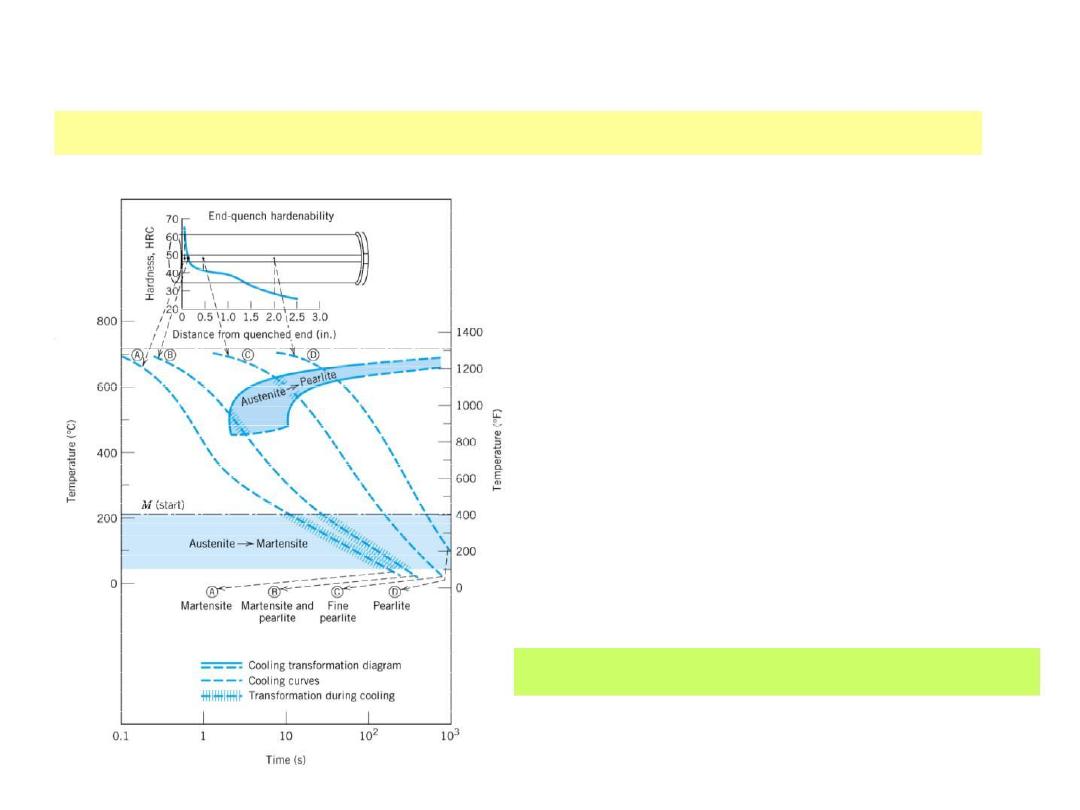

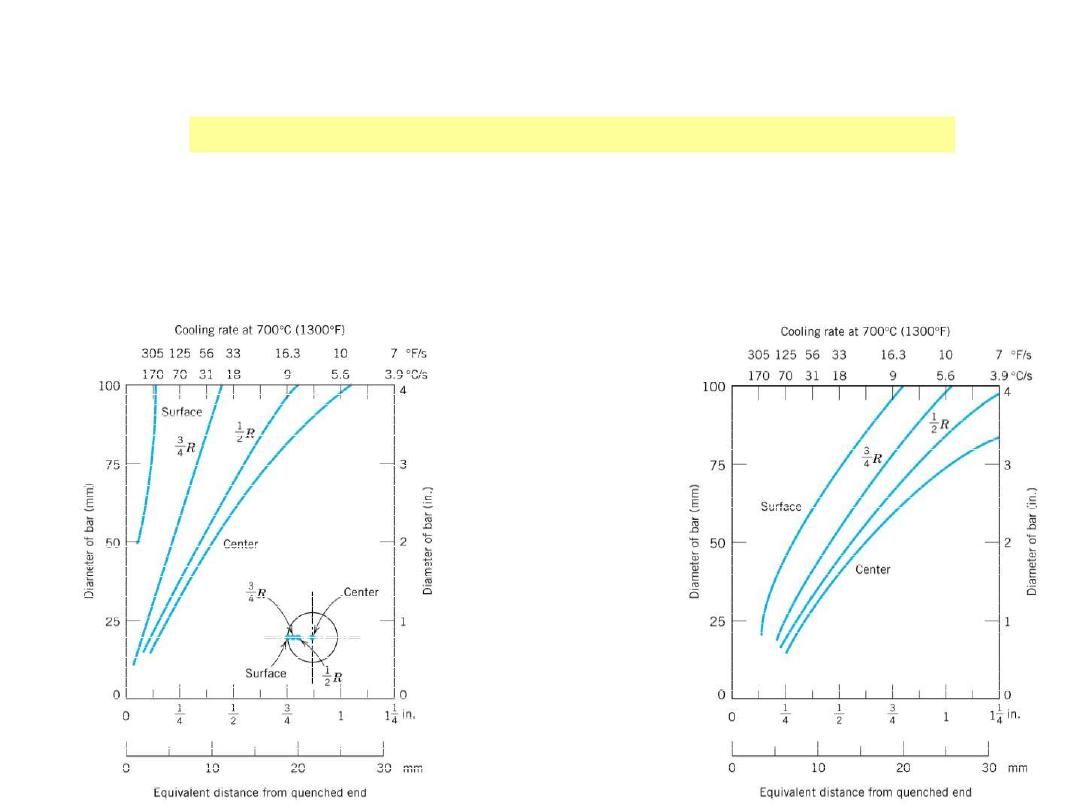

WHY HARDNESS CHANGES W/POSITION?

Because the cooling rate varies with position !!

• Note: cooling rates before reaching

Austenite

– Martensite transformation

are in the range 1 -50 C/s

• Measuring cooling rates at every point

(e.g. by thermocouples) and finding rates

correlations with the hardness one may

develop quenching rate

– hardness diagram

•But how one can change quenching rate?

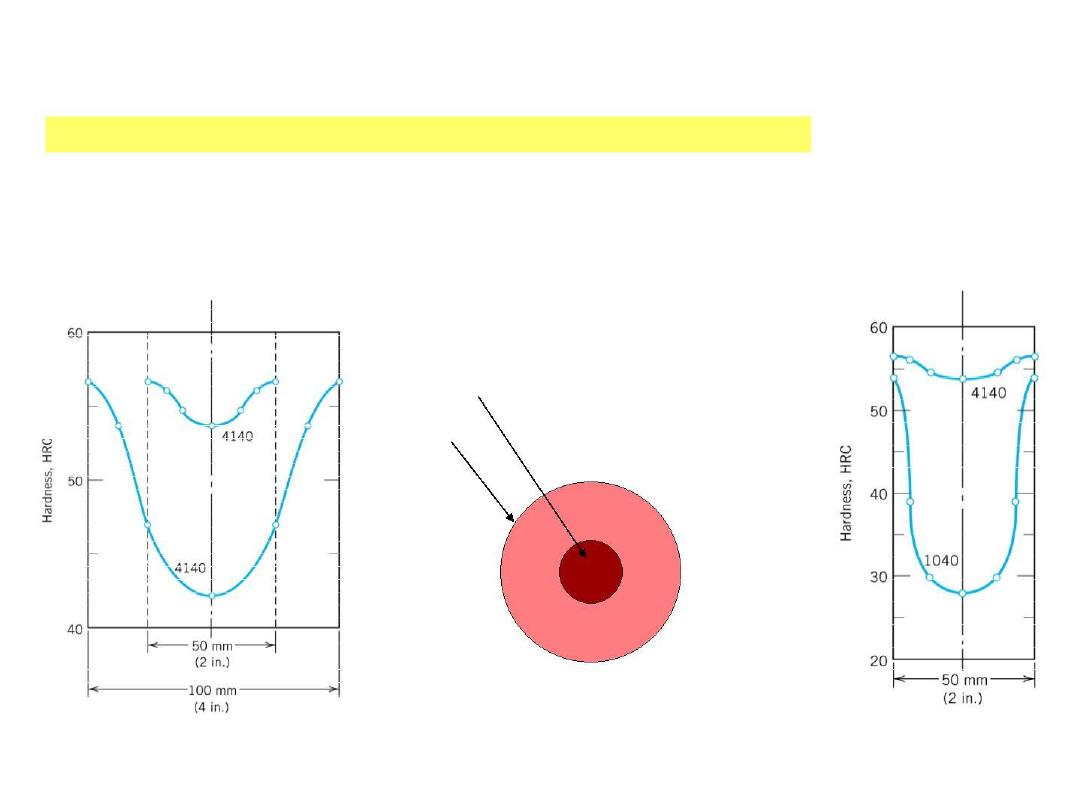

QUENCHING GEOMETRY

•

Effect of geometry:

When surface-to-volume ratio increases:

rate increases --cooling

--hardness increases

Position Cooling rate Hardness

center

surface

small

large

small

large

QUENCHING MEDIUM

• Effect of quenching medium:

Medium

air

oil

Severity of Quench

small

moderate

large

Hardness

small

moderate

large

water

Water

Oil

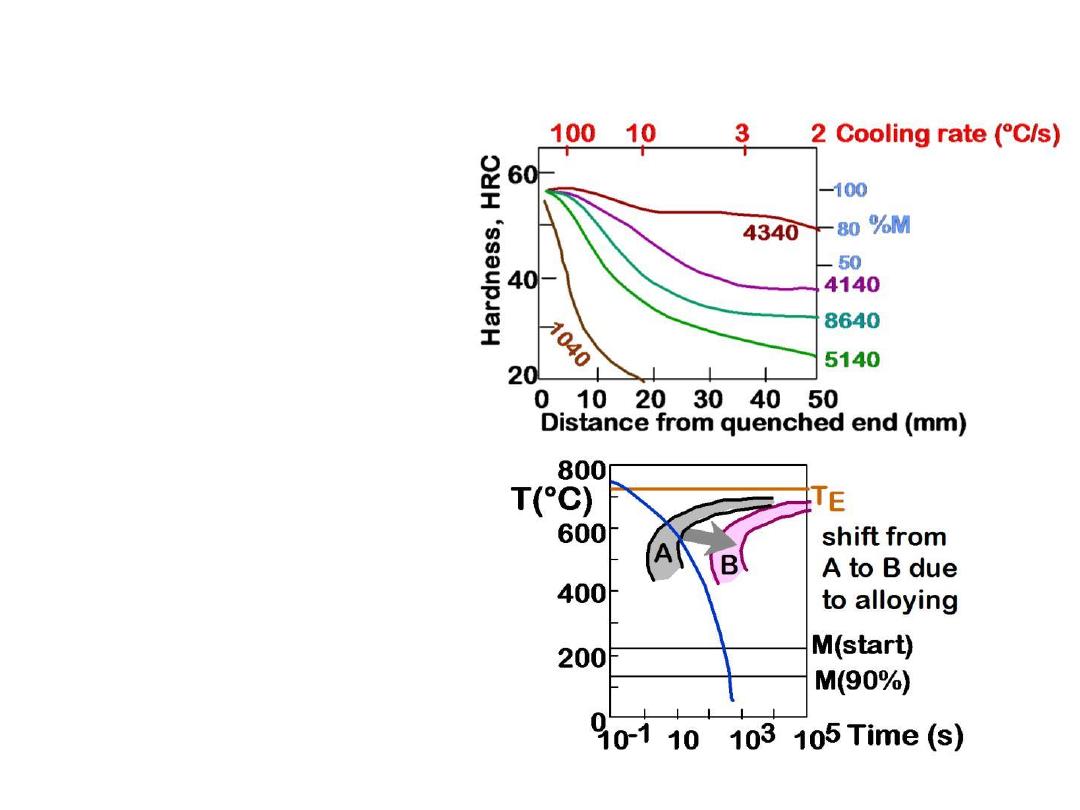

HARDENABILITY VS ALLOY CONTENT

•

•

Jominy end quench

results, C = 0.4wt%C

"Alloy Steels"

(4140, 4340, 5140, 8640)

--contain Ni, Cr, Mo

(0.2 to 2wt%)

--these

elements shift

the "nose".

--martensite is easier to form.

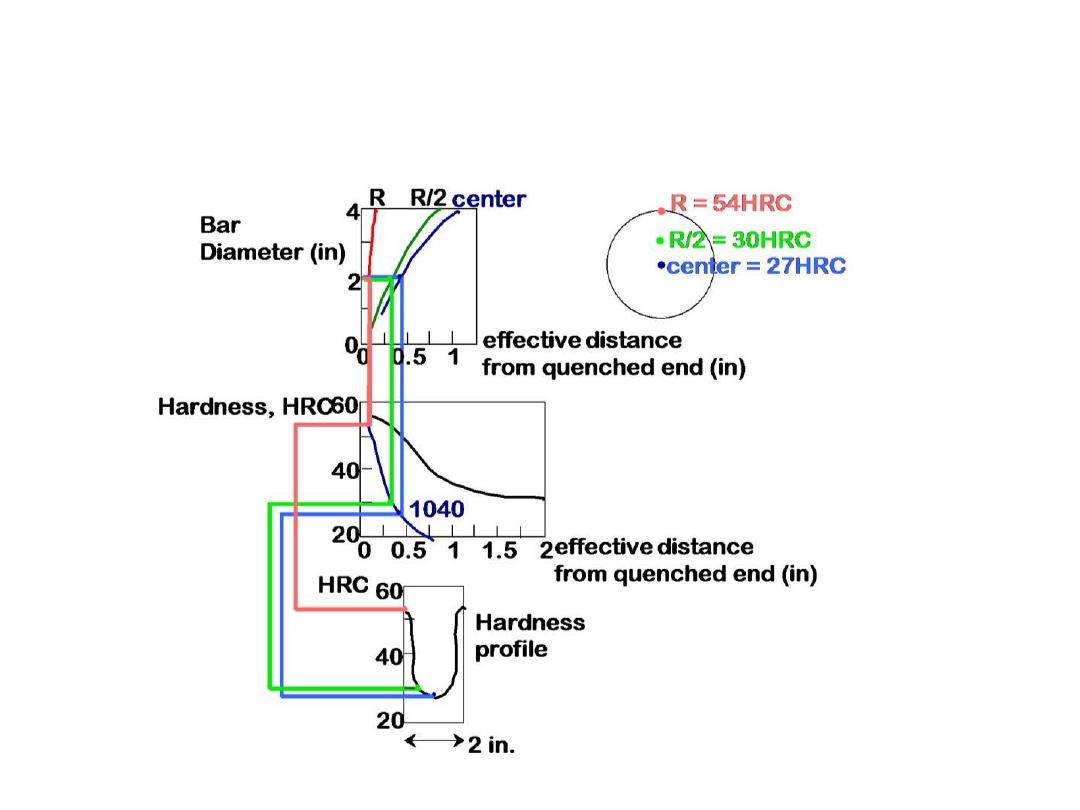

PREDICTING HARDNESS PROFILES

• Ex: Round bar, 1040 steel, water quenched, 2" diam.

SUMMARY

• Steels: increase TS, Hardness (and cost) by adding

--C (low alloy steels)

--Cr, V, Ni, Mo, W (high alloy steels)

--ductility usually decreases w/additions.

• Non -ferrous:

--Cu, Al, Ti, Mg, Refractory, and noble metals.

• Fabrication techniques:

--forming, casting, joining.

•

Hardenability

--increases with alloy content.

• Precipitation hardening

--effective means to increase strength in

Al, Cu, and Mg alloys.