DIABETES MELLITUS •

11

407

Twice-daily injections: short-acting and intermediate-acting insulin

(usually soluble and isophane insulins), given in combination before break-

fast and the evening meal. Usually two-thirds of the total daily insulin

requirement is given in the morning in a ratio of 1 : 2, short : intermediate-

acting insulins. The remaining third is given in the evening. Pre-mixed

formulations are available containing different proportions of soluble and

isophane insulins (e.g. 30 : 70 and 50 : 50). These are useful in patients who

have diffi culty mixing insulins, but preclude adjustment of the individual

components.

Multiple injections: short-acting insulin taken before each meal, and

intermediate-acting insulin injected at bedtime (basal–bolus regimen). This

allows greater freedom for timing of meals. Fast-acting insulin analogues

may be used before meals, and are particularly useful if the evening meal

is late, as they do not induce nocturnal hyperinsulinaemia. However, a long

interval between meals allows the blood glucose to rise. A common problem

is fasting hyperglycaemia (the ‘dawn phenomenon’) caused by the release

of counter-regulatory hormones during the night, which increases insulin

requirement before wakening.

Complications of insulin therapy

• Hypoglycaemia. • Weight gain. • Peripheral oedema (insulin treatment

causes salt and water retention in the short term). • Insulin antibodies

(animal insulins). • Local allergy (rare). • Lipodystrophy at injection sites.

FUTURE THERAPIES

Transplantation of isolated pancreatic islets (usually into the liver via the

portal vein) has been achieved in a small number of humans. The develop-

ment of methods of inducing tolerance to transplanted islets and the use of

stem cells or transformation of hepatocytes to make insulin by genetic

engineering mean that this may still prove the most promising approach in

the long term.

Whole pancreas transplantation presents particular problems relating to

the exocrine pancreatic secretions, and long-term immunosuppression is

necessary. While results are steadily improving, they remain less favourable

than for renal transplantation. However, it is questionable whether it will

ever be considered justifi able to perform transplantation in young diabetic

patients before vascular disease is clinically apparent.

Alternative methods and routes of insulin delivery other than subcutane-

ous injection are being sought. Inhaled, oral and transcutaneous (patch)

routes of delivery are being explored.

LONG-TERM COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES

People with diabetes have a mortality rate double that of age- and sex-

matched controls. Large blood vessel disease accounts for 70% of all

408

DIABETES MELLITUS •

11

deaths. Atherosclerosis in diabetic patients occurs earlier and is more exten-

sive and severe. Diabetes enhances the effects of the other major cardio-

vascular risk factors: smoking, hypertension and dyslipidaemia.

Microangiopathy (small blood vessel disease) is a specifi c complication

of diabetes. It contributes to mortality by provoking renal failure (diabetic

nephropathy) and causes substantial morbidity and disability: blindness,

diffi culty in walking, chronic foot ulceration, and bowel and bladder dys-

function. The risk of microangiopathy is related to the duration and degree

of hyperglycaemia. Diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy and

atherosclerosis are thought to result from the local response to the general-

ised vascular injury.

Preventing diabetes complications

No study has produced any evidence of improved glycaemic control revers-

ing either retinopathy or nephropathy, and in some cases retinopathy wors-

ened abruptly soon after control was improved. Despite this, in the long

term the rate of progression of both retinopathy and nephropathy was

reduced by continuing better control. The Diabetes Control and Complica-

tions Trial (DCCT) was a large study in type 1 diabetic patients to answer

the question: are diabetic complications preventable? The trial demon-

strated a 60% overall reduction in the risk of developing diabetic complica-

tions in those on intensive therapy with strict glycaemic control (mean

HbA

1c

7%), compared with those on conventional therapy (HbA

1c

9%). This

trial showed that diabetic complications are preventable and treatment aim

should be ‘near-normal’ glycaemia. Strict glycaemic control was compli-

cated by weight gain and severe hypoglycaemic episodes. This increased

risk of hypoglycaemia may alter the risk : benefi t ratio in patients who have

impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia, have severe macrovascular disease

(previous myocardial infarction/cerebrovascular accident), or are at the

extremes of life.

The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) in type 2 diabetes found

that diabetic complications were reduced and progression was slower with

good glycaemic control (mean HbA

1c

7%) and effective treatment of hyper-

tension, irrespective of the type of therapy used. RCTs have also shown

that aggressive management of lipids and BP limits the complications of

diabetes. ACE inhibitors are valuable in improving outcome in heart disease

and in preventing diabetic nephropathy.

DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

Diabetic retinopathy is a common cause of blindness in adults in developed

countries. Hyperglycaemia increases retinal blood fl ow and metabolism,

and has direct effects on retinal endothelial cells, resulting in impaired

vascular autoregulation. This leads to chronic retinal hypoxia which stimu-

lates production of growth factors causing new vessel formation and

increased vascular permeability.

DIABETES MELLITUS •

11

409

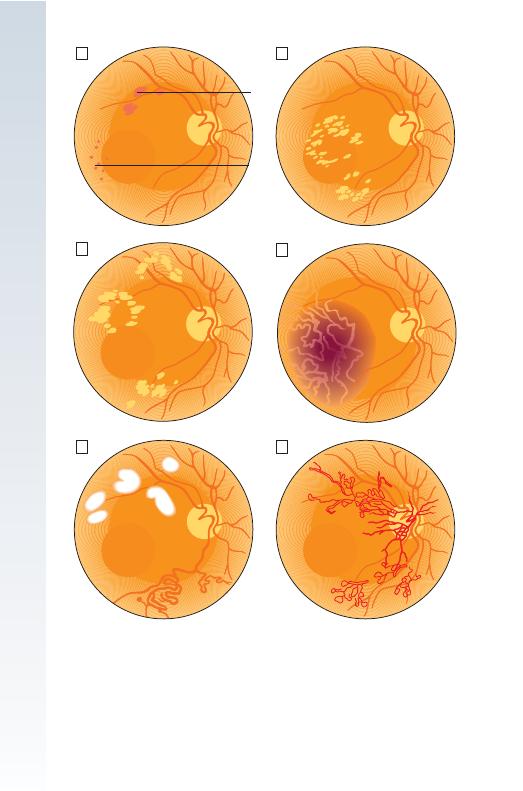

Clinical features

Microaneurysms: Tiny, discrete, circular, dark red spots near to the

retinal vessels (Fig. 11.3A) are the earliest abnormality detected.

Haemorrhages: These are found in the deeper layers of the retina and

are round (‘blot’ haemorrhages, Fig. 11.3A). They are often grouped with

microaneurysms as ‘dots and blots’. Superfi cial fl ame-shaped haemor-

rhages in the nerve fi bre layer also occur, particularly in hypertensive

patients.

Exudates: Characteristic of diabetic retinopathy, these vary in size from

specks to confl uent patches, and tend to occur around the macula (Fig.

11.3B).

Cotton wool spots: Usually occurring within fi ve disc diameters of the

optic disc (Fig. 11.3E), these represent arteriolar occlusions causing retinal

ischaemia and occur in pre-proliferative, often rapidly advancing retinopa-

thy or uncontrolled hypertension.

Intraretinal microvascular abnormalities: These are dilated, tortuous

capillaries representing patent capillaries in an area where most have been

occluded (severe pre-proliferative retinopathy).

Neovascularisation: Vessels arise on the optic disc or retina in response

to an ischaemic retina (Fig. 11.3F). They are fragile and leaky, causing

haemorrhage which may be pre-retinal or vitreous. Leaking serous products

stimulate a connective tissue reaction, called gliosis, by which retinal

detachment can occur due to adhesions between the vitreous and the

retina.

Venous changes: These range from venous dilatation (background)

to venous beading and increased tortuosity (‘oxbow lakes’/loops, pre-

proliferative retinopathy).

Rubeosis iridis: This is the development of new vessels on the anterior

surface of the iris. Vessels may obstruct the drainage angle, causing second-

ary glaucoma.

Classifi cation

A classifi cation based on prognosis is shown in Box 11.11. Background

retinopathy does not threaten vision unless associated with macular disease.

Macular oedema is suspected if there is impairment of visual acuity with

peripheral non-proliferative retinopathy. New vessels may be symptomless

until sudden visual loss occurs from pre-retinal or vitreous haemorrhage.

This resolves, although recurrence is common. Fibrous tissue may interfere

with vision by obscuring the retina or causing detachment.

Prevention

Good glycaemic control reduces the risk of retinopathy. Early diagnosis

and treatment is important for patients with type 2 diabetes; 25% present

with established retinopathy. A rapid reduction in blood glucose may cause

an initial deterioration of retinopathy by causing relative ischaemia.

Improvement in glycaemic control should therefore be effected gradually.

BP lowering is of proven benefi t. Elevated cholesterol is a risk factor, but

410

DIABETES MELLITUS •

11

Blots

Dots

C

E

A

D

F

B

Fig. 11.3 Diagrammatic representation of diabetic eye disease.

䊐

A Background diabetic

retinopathy showing microaneurysms and blot haemorrhages.

䊐

B Background retinopathy

showing exudates.

䊐

C Maculopathy with exudates.

䊐

D Maculopathy showing oedema.

䊐

E Pre-proliferative retinopathy showing venous changes and cotton wool spots.

䊐

F Proliferative

retinopathy showing neovascularisation.

DIABETES MELLITUS •

11

411

evidence for statin use is awaited. Regular screening for retinopathy is

essential in all diabetic patients, especially those with risk factors such as

long duration of diabetes, hypertension, poor control, pregnancy, smoking,

excess alcohol and evidence of microangiopathy. The preferred screening

option is a digital imaging photographic system, with referral to an oph-

thalmologist when needed.

Management

Severe non-proliferative and proliferative retinopathy is treated with retinal

photocoagulation, which has been shown to reduce severe visual loss by

85% (50% in maculopathy). Argon laser photocoagulation is used to:

• Destroy areas of retinal ischaemia. • Seal leaking microaneurysms. •

Reduce macular oedema. • Gliose new vessels on the retinal surface.

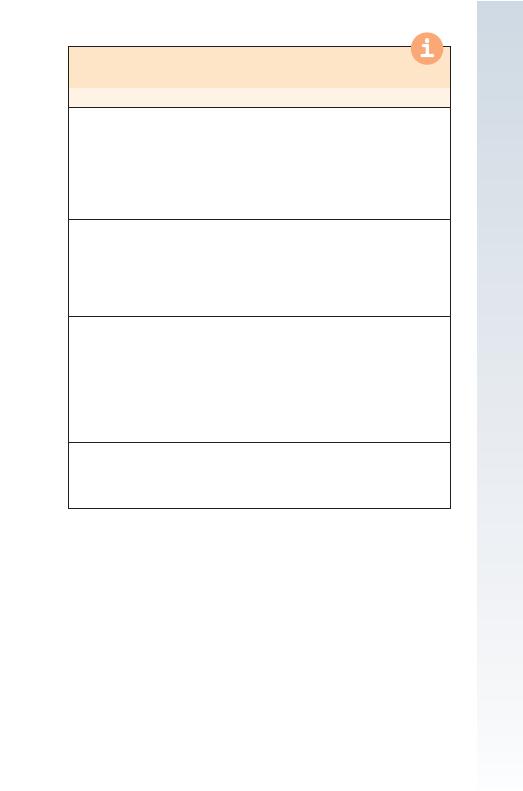

11.11 CLASSIFICATION OF DIABETIC RETINOPATHY BY

PROGNOSIS FOR VISION

Type of retinopathy

Prognosis/Action required

Background retinopathy

Venous dilatation

Peripheral microaneurysms, blot haemorrhages,

exudates

No immediate threat to vision

Control blood glucose, lipids

and BP, advise to stop

smoking

Fundoscopy every 6–12 mths,

refer if progression

Maculopathy

Macular exudation, haemorrhage, ischaemia

Macular oedema

Sight-threatening—refer for

specialist opinion

Review of risk factors,

glycaemic control, BP and lipid

levels

Pre-proliferative retinopathy

Venous loops and beading

Clusters of microaneurysms, blot

haemorrhages, large retinal haemorrhages

Intraretinal microvascular abnormalities, cotton

wool spots

Macular oedema

Perimacular exudates

± haemorrhages

Sight-threatening—refer for

specialist opinion

Rapid lowering of blood

glucose may worsen

retinopathy (see text)

Proliferative retinopathy

Pre-retinal haemorrhage

Neovascularisation

Fibrosis, exudative maculopathy

Sight-threatening—urgent

review and treatment by

specialist mandatory

412

DIABETES MELLITUS •

11

Patients must be reviewed regularly to check for recurrence. Extensive

bilateral photocoagulation can cause visual fi eld loss, interfering with

driving and night vision. Vitrectomy may be used where visual loss is due

to recurrent vitreous haemorrhage which has failed to clear, or retinal

detachment resulting from retinitis proliferans. Rubeosis iridis is managed

by early pan-retinal photocoagulation.

OTHER CAUSES OF VISUAL LOSS IN DIABETES

Around 50% of visual loss in people with type 2 diabetes is due to causes

other than diabetic retinopathy. These include:

• Cataract. • Macular degeneration. • Retinal vein occlusion. • Retinal

arterial occlusion. • Ischaemic optic neuropathy. • Glaucoma.

Cataract occurs prematurely in people with diabetes due to the metabolic

insult to the lens.

DIABETIC NEPHROPATHY

Diabetic nephropathy is among the most common causes of end-stage renal

failure (ESRF) in developed countries. About 30% of patients with type 1

diabetes have developed diabetic nephropathy after 20 yrs, but the risk

after this time falls to less than 1% per year. Risk factors for developing

nephropathy include:

• Poor glycaemic control. • Duration of diabetes. • Asian ethnicity. • Hyper-

tension. • Other microvascular complications. • A family history of

nephropathy or hypertension.

Pathologically, thickening of the glomerular basement membrane is fol-

lowed by nodular deposits (Kimmelstiel–Wilson nodules). As glomerulo-

sclerosis worsens, heavy proteinuria develops, sometimes in the nephrotic

range, and renal function progressively deteriorates.

Diagnosis and screening

Microalbuminuria (30–300 mg/24 hrs) is a risk factor for developing overt

diabetic nephropathy, although it is also found in other conditions. Progres-

sively increasing albuminuria, or albuminuria accompanied by hyperten-

sion, is more likely to be due to early diabetic nephropathy. Patients with

type 1 diabetes should be screened annually from 5 yrs after diagnosis;

those with type 2 diabetes should be screened annually from the time of

diagnosis.

Management

If nephropathy is identifi ed, progression can be reduced by improved blood

glucose control, and aggressive reduction of BP and other cardiovascular

risk factors.

• ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers have been shown to

provide greater benefi t than equal BP reduction achieved with other drugs.

• Diabetic control becomes diffi cult in renal impairment. Metformin should

be stopped when creatinine is

>150 μmol/l (1.7 mg/dl; risk of lactic acido-

DIABETES MELLITUS •

11

413

sis). Long-acting sulphonylureas should be replaced by short-acting agents.

• Renal replacement therapy may benefi t diabetic patients at an earlier stage

than other ESRF patients. • Renal transplantation can improve quality of

life, although macrovascular disease and neuropathy/retinopathy show con-

tinued progression. • Pancreatic transplantation can produce insulin inde-

pendence and can reverse microvascular disease, but the supply of organs

is limited.

DIABETIC NEUROPATHY

This complication affects approximately 30% of patients. It is symptomless

in the majority and can occur in motor, sensory and autonomic nerves.

Prevalence is related to the duration of diabetes and the degree of metabolic

control.

Clinical features

Symmetrical sensory polyneuropathy: There is diminished perception

of vibration sensation distally, ‘glove-and-stocking’ impairment of all other

modalities of sensation, and loss of tendon refl exes in the lower limbs.

Although frequently asymptomatic, it can cause paraesthesia in the feet or

hands, pain on the anterior aspect of the legs (worse at night), burning

sensations in the soles of the feet, hyperaesthesia and a wide-based gait.

Toes may be clawed with wasting of the interosseous muscles. A diffuse

small-fi bre neuropathy causes altered pain and temperature sensation and

is associated with symptomatic autonomic neuropathy; characteristic fea-

tures include foot ulcers and Charcot neuroarthropathy. Management

includes strict glycaemic control, tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline,

imipramine), anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, gabapentin) and opioids

(tramadol, oxycodone).

Asymmetrical motor diabetic neuropathy (diabetic amyotrophy): This

presents as severe and progressive weakness and wasting of the proximal

muscles of the lower (occasionally upper) limbs, accompanied by severe

pain, hyperaesthesia and paraesthesia. There may also be marked loss of

weight (‘neuropathic cachexia’), tendon refl exes may be absent, and the

CSF protein is often raised. This condition is thought to involve acute inf-

arction of the lumbosacral plexus. Although recovery usually occurs within

12 mths, some defi cits become permanent. Management is mainly

supportive.

Mononeuropathy: Either motor or sensory function can be affected

within a single peripheral or cranial nerve. Unlike other neuropathies,

mononeuropathies are severe and of rapid onset; the patient usually recov-

ers. Most commonly affected nerves are 3rd and 6th cranial nerves, femoral

and sciatic nerves. Multiple nerves are affected in mononeuritis multiplex.

Nerve compression palsies commonly affect the median nerve and lateral

popliteal nerve (foot drop).

Autonomic neuropathy: This is less clearly related to poor metabolic

control, and improved control rarely improves symptoms. Clinical features

414

DIABETES MELLITUS •

11

and management are shown in Box 11.12. Within 10 yrs of developing

autonomic neuropathy, 30–50% of patients are dead. Those with postural

hypotension have the highest subsequent mortality.

THE DIABETIC FOOT

Tissue necrosis in the feet is a common reason for hospital admission in

diabetic patients. Foot ulceration occurs as a result of often trivial trauma

in the presence of neuropathy (peripheral and autonomic) and/or peripheral

vascular disease; infection occurs as a secondary phenomenon. In most

cases all three components are involved in producing tissue necrosis. Most

ulcers are neuropathic or neuro-ischaemic in type. The most common cause

of ulceration is a plaque of callus skin beneath which tissue necrosis occurs,

eventually breaking through to the surface.

Management

Preventative management is the most effective method of dealing with the

diabetic foot. Regular podiatry, patient education and orthotic footwear

(preventing recurrence and protecting deformed feet) are required. Medical

management includes:

• Removal of callus skin (podiatrist only). • Treatment of infection (often

protracted courses, especially in the presence of osteomyelitis). • Avoidance

of weight-bearing. • Good glycaemic control. • Control of oedema. • Angi-

ography if the foot is ischaemic: to assess feasibility of vascular reconstruc-

tion. • Amputation: if there is extensive tissue/bony destruction or intractable

ischaemic pain when vascular reconstruction is not possible or has failed.

11.12 CLINICAL FEATURES AND MANAGEMENT OF

AUTONOMIC NEUROPATHY

Feature

Management

Postural hypotension (drop in systolic

pressure of

≥20 mmHg)

Fludrocortisone, support stockings

Gastroparesis

Metoclopramide, erythromycin

Diarrhoea/constipation

Loperamide, stimulant laxatives

Atonic bladder

Intermittent self-catheterisation

Hyperhydrosis

Topical/oral anti-muscarinics

Erectile dysfunction (30% of males)

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors,

prostaglandin injections