INTRODUCTION

Eye movements may be abnormal because there is:

•

an abnormal position of the eyes;

•

a reduced range of eye movement;

•

an abnormality in the form of eye movement

.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

see (Fig. 15.1)

Each eye can be abducted (away from the nose) or adducted (towards the nose) or

may look up (elevation) or down (depression).

The cardinal positions of gaze for assessing a muscle palsy are: gaze right, left, up,

down, and gaze to the right and left in the up and down positions.

Six extraocular muscles control eye movement.

The medial and lateral recti bring about horizontal eye movements causing

adduction and abduction respectively.

The vertical recti elevate and depress the eye in abduction.

The superior oblique causes depression in the adducted position and the inferior

oblique causes elevation in the adducted position.

The vertical muscles all have additional secondary actions (intorsion and

extorsion, circular movement of the eye).

Ophthalmology

Zakho hospital

Eye movement

13 April 2017 Dr. Nzar

2

Three cranial nerves supply these muscles (see p. 15) whose nuclei are found in the

brainstem, together with connections linking them with

Clinically, eye movement disorders are best described under four headings (which

are not mutually exclusive):

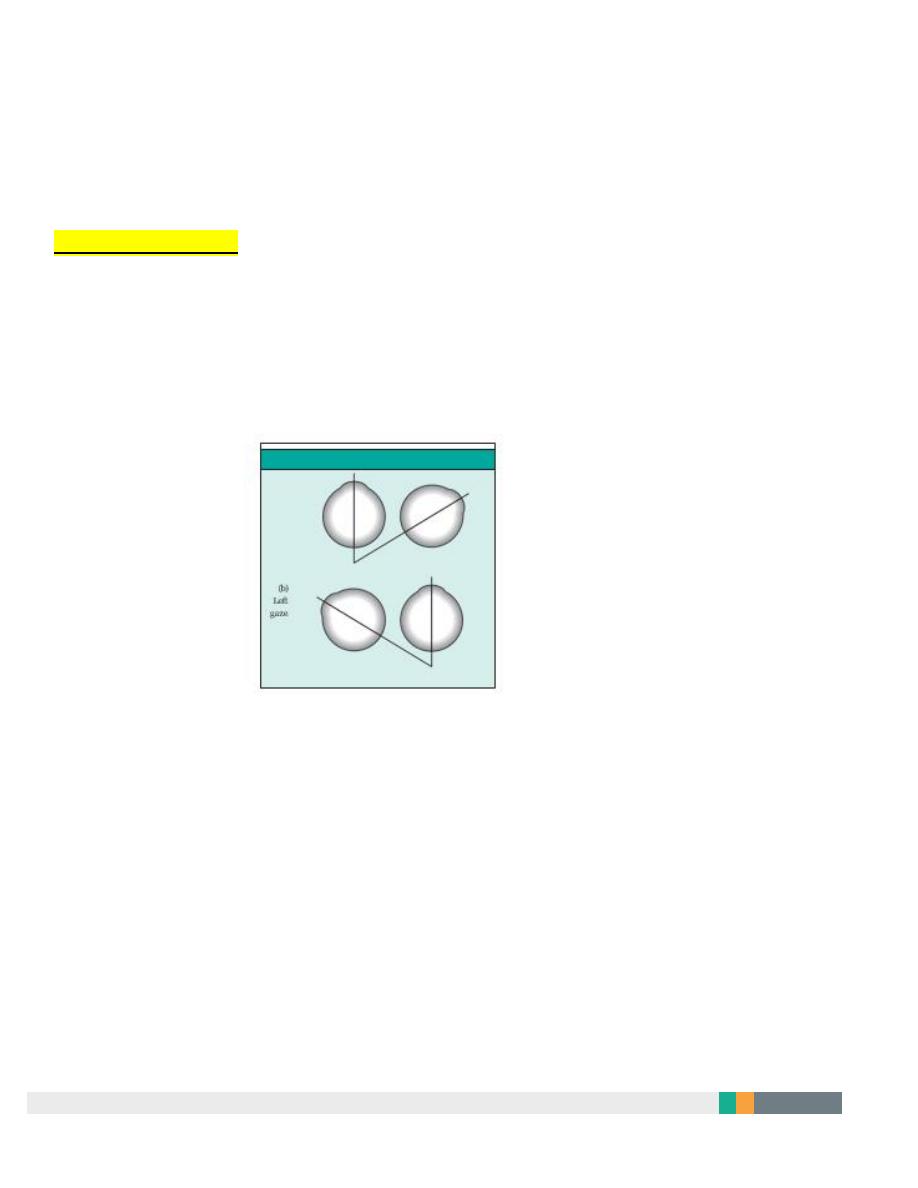

1 In a non-paralytic (concomittant) squint the movements of both eyes are full (there

is no paresis) but only one eye is directed towards the fixated target (Fig. 15.2).

The angle of deviation is constant and unrelated to the direction of gaze. This is the

squint that is usually seen in childhood.

NON– PARALYTIC SQUIN

a)straight a head

B) left gaze

Fig. 15.2 The pattern of eye movement seen in a non-paralytic squint: (a) the right eye is divergent in the primary position of gaze (looking straight

ahead);

(b) when the eyes look to the left the angle of deviation between the visual axis (a line passing through the point of fixation and the foveola) of the

two eyes is unchanged

.

3

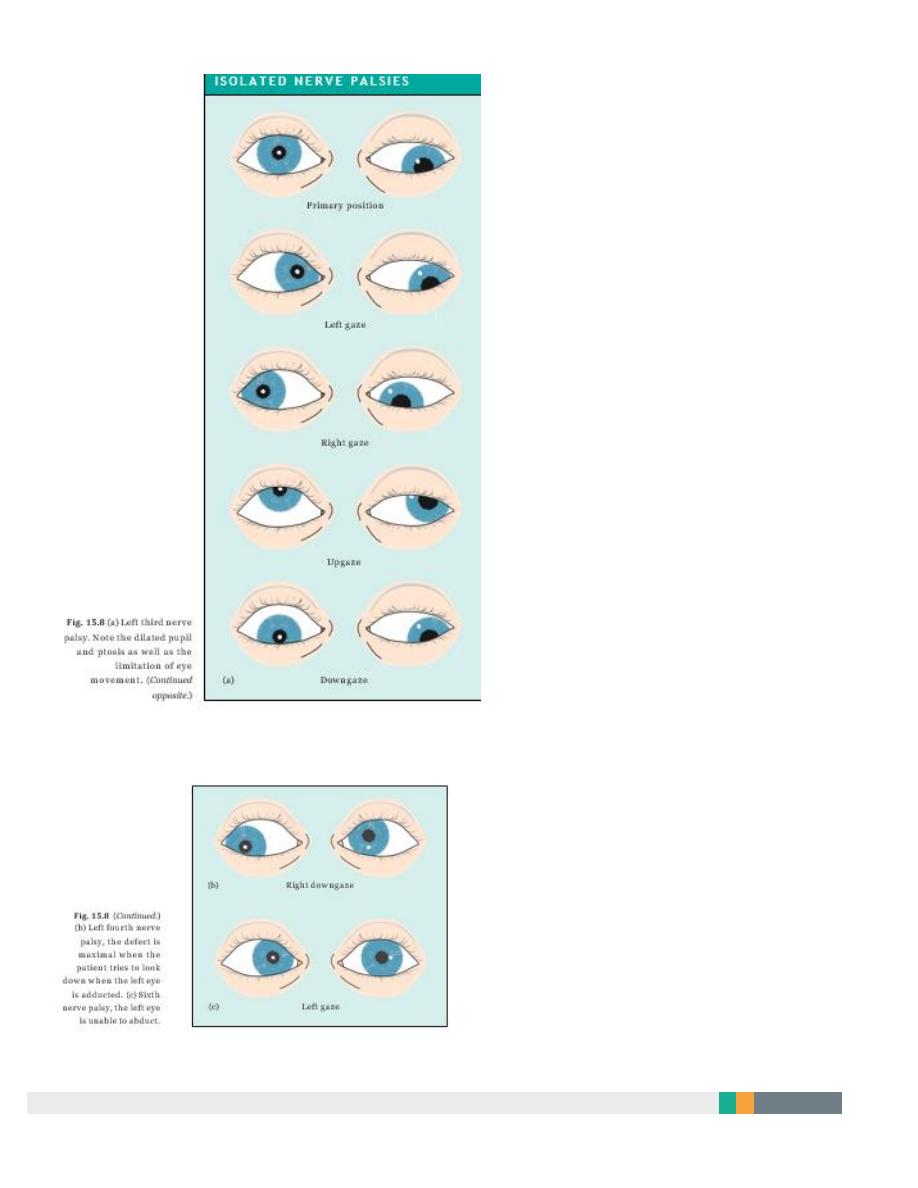

2-In a paralytic (incomitant squint.) squint there is underaction of one or more of

the eye muscles due to a nerve palsy, extraocular muscle disease or tethering of the

globe. The size of the squint is dependent on the direction of gaze and, for a nerve

palsy, is greatest in the field of action (the direction in which the muscle would

normally take the globe) of the affected muscle.

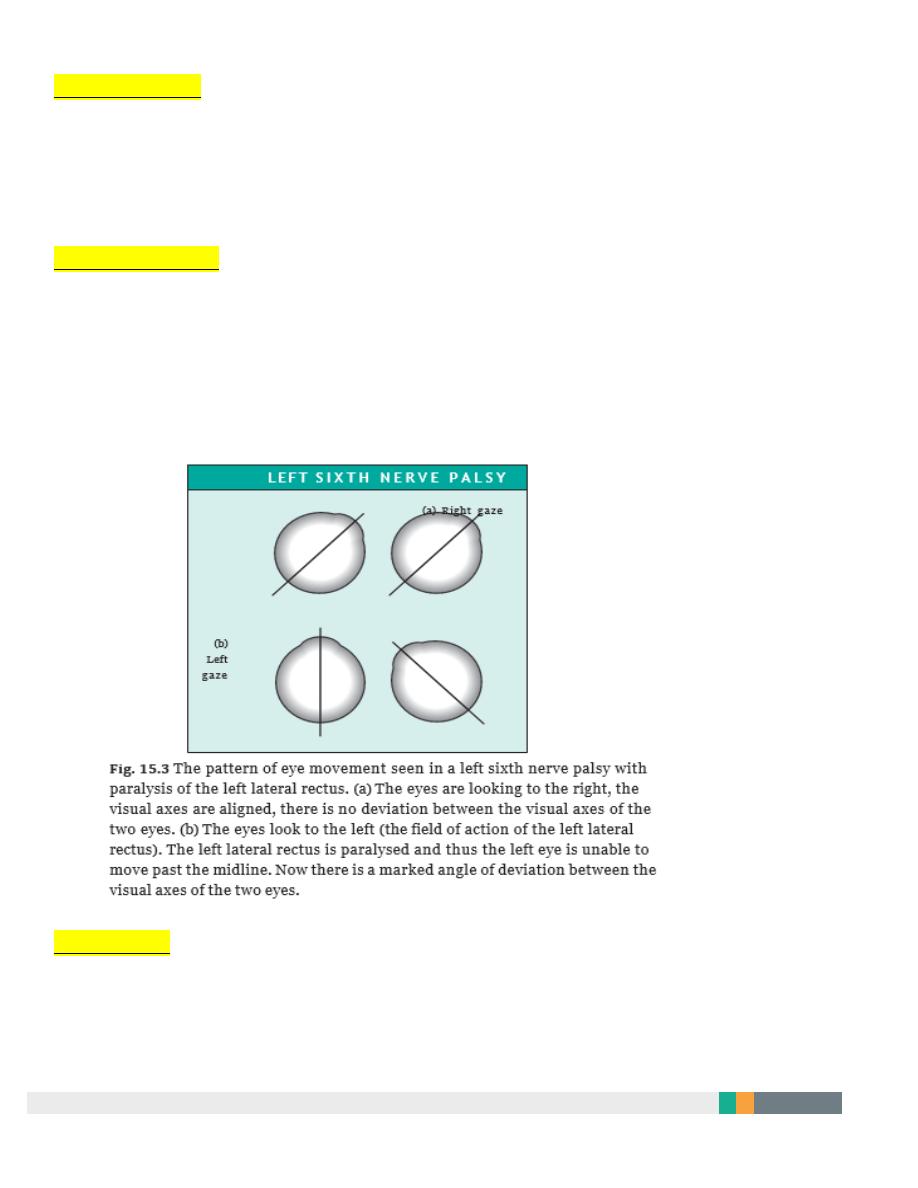

3-In gaze palsies there is a disturbance of the supranuclear coordination of eye

movements; pursuit and saccadic eye movements may also be affected if the

cortical pathways to the nuclei controlling eye movements are interrupted (Fig. 15.3).

4 Disorders of the brainstem nuclei or vestibular input may also result in a form of

oscillating eye movement termed nystagmus.

4

NON-PARALYTIC SQUINT

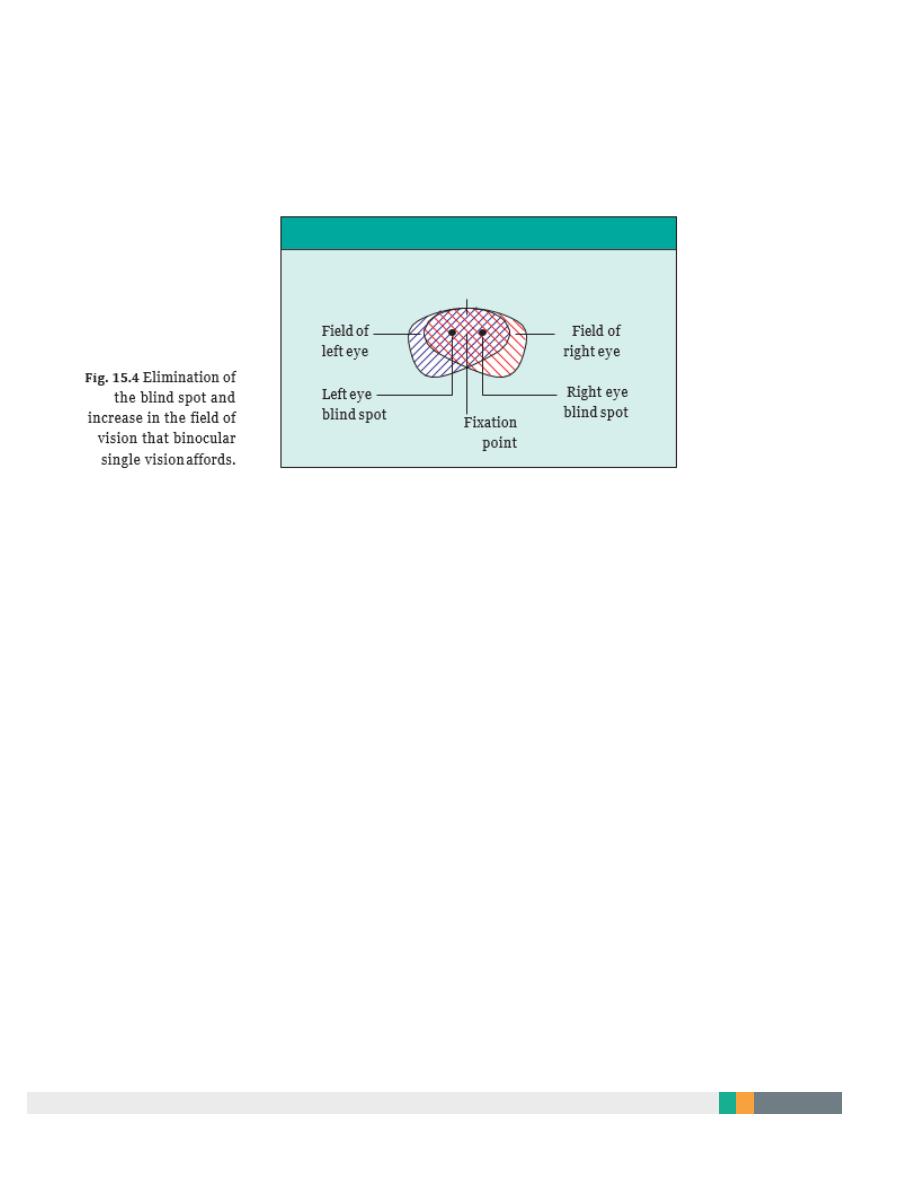

Binocular single vision (Fig. 15.4)

In the absence of a squint the eyes are directed towards the same object.

Their movements are coordinated so that the retinal images of an object fall on

corresponding points of each retina.

These images are fused centrally, so that they are interpreted by the brain as a single

image.

This is termed binocular single vision. Because each eye views an object from a

different angle, the retinal images do not correspond precisely; the closer the object

the greater this disparity.

These differences allow a three dimensional percept to be constructed. This is

termed stereopsis.

The development of stereopsis requires that eye movements and visual alignment

are coordinated in approximately the first five years of life.

1. Binocular single vision and stereopsis afford certain

Advantages to the individual:

•

they increase the field of vision;

•

they eliminate the blind spot, since the blind spot of one eye falls in the seeing

field of the other;

•

they provide a binocular acuity which is greater than monocular acuity;

•

stereopsis provides depth perception.

5

BINOCULAR VISUAL FIELD

Field of binocular single visin

If the visual axes of the two eyes are not aligned, binocular single vision is not

possible. This results in:

•

Diplopia. An object is seen to be in two different places.

•

Visual confusion. Two separate and different objects appear to be at the same

point.

•

(strabismic amblyopia) when the vision is tested separately in each eye.

Amblyopia will only develop if the squint constantly affects the same eye.

•

Some children alternate the squinting eye. These children will not develop

amblyopia, but they do not develop stereopsis either.

6

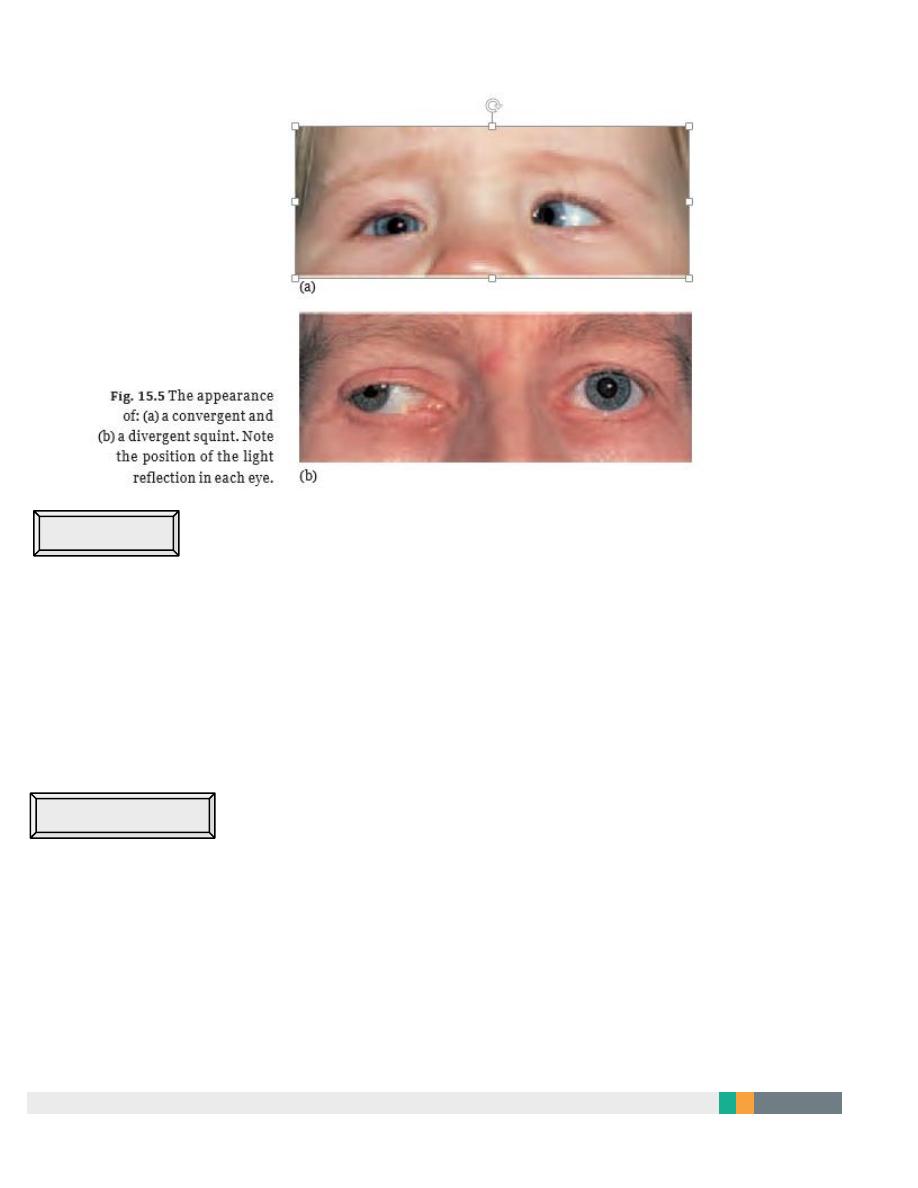

Aetiology of non-paralytic squint (

Fig. 15.5)

1 May develop in an otherwise normal child with normal eyes.The cause of the problem

in these patients remains obscure. It is thought to be caused by an abnormality in the

central coordination of eye movements.

2 May be associated with ocular disease:

(a) A refractive error which prevents the formation of a clear image on the retina. This

is the most common factor. If the refractive error is dissimilar in the two eyes

(anisometropia) one retinal image will be blurred.

(b) Opacities in the media of the eye blurring or preventing the formation of the retinal

image (i.e. corneal opacities or cataract).

(c) Abnormalities of the retina preventing the translation of a correctly formed image

into neural impulses.

(d) In a child equally long sighted (hypermetropic) in both eyes a convergent squint

may develop because the increased accommoda- tion of the lens (which will correct

the hypermetropic error) needed to achieve a clear retinal image for distant objects

(and even more for near) will be associated with excessive convergence. Here squint

may only occur on attempted convergence, in which case amblyopia does not

develop since binocular visual alignment remains normal for some of the time during

distant viewing.

7

HISTORY

The presence of a squint in a child may be noted by the parents or detected at pre-school or

school screening clinics. It may be intermittent or constant. There may be a family history of

squint or refractive error. The following should be noted:

• when the squint is present;

• how long a squint has been present for;

• past medical, birth and family history of the child.

EXAMINATION

First the patient is observed for features that may simulate a squint. These include:

• epicanthus (a crescentic fold of skin on the side of the nose that incompletely covers

the inner canthus);

• facial asymmetry.

8

The corneal reflection of a pen torch held 33 cm in front of the subject is a guide to eye

position. If the child is squinting the reflection will be central in the fixating eye and deviated

in the squinting eye (Fig. 15.5).

A cover/uncover test (Fig. 15.6) is next performed to detect a manifest squint (a tropia).

• The right eye is completely covered for a few seconds whilst holding a detailed near

target (usually a small picture or a toy) in front of the subject as a fixation target.

• The left eye is closely observed. If it has been maintain- ing fixation it should not move.

If it moves outwards to take up fixation an esotropia or convergent squint is present. If

it moves inwards to take up fixation an exotropia or divergent squint is present.

• The cover is removed from the right eye and the left eye covered, this time closely

observing the right. If it moves outwards to take up fixation an esotropia or convergent

squint is present. If it moves inwards to take up fix- ation an exotropia is present. If

there is no movement no squint is present.

The test is repeated for a distance object sited at 6 metres and for a far distant object. It will

also reveal a vertical squint.

If no abnormal eye movement is seen an alternate cover test is performed. This will reveal

the presence of a latent squint (a phoria), that is one which occurs only in the absence of

bifoveal visual stimulation. It is not really an abnormal condition and can be demonstrated in

most people who otherwise have normal binocular single vision.

This time the cover is moved rapidly from one eye to the other a couple of times. This

dissociates the eyes (there is no longer bifoveal stimulation).The right eye is now occluded

and as the occluder is removed any movement in the right eye is noted. If the eye is seen to

move inwards an exophoria (latent divergence) is present and the eye has moved inwards to

take up fixation. If the eye is seen to move outwards to take up fixation an esophoria (latent

convergence) is present. Exactly the same movements would be seen in the left eye if it were

covered following dissociation.

In an eye clinic the squint can be further assessed with the synoptophore (see p. 32). This

instrument together with special three- dimensional pictures can also be used to determine

whether the eyes are used together and whether stereopsis is present

9

Refractive error is measured (following topical administration of atropine or cyclopentolate

eye drops to paralyse accommodation and dilate the pupil). The eye is then examined to

exclude opacities of the cornea, lens or vitreous and abnormalities of the retina or optic disc.

10

TREATMENT

A non-paralytic squint with no associated ocular disease is treated as follows:

• Any significant refractive error is first corrected with glasses.

• If amblyopia is present and the vision does not improve with glasses the better seeing

eye is patched to try and stimulate the amblyopic eye thereby increasing its visual

acuity.

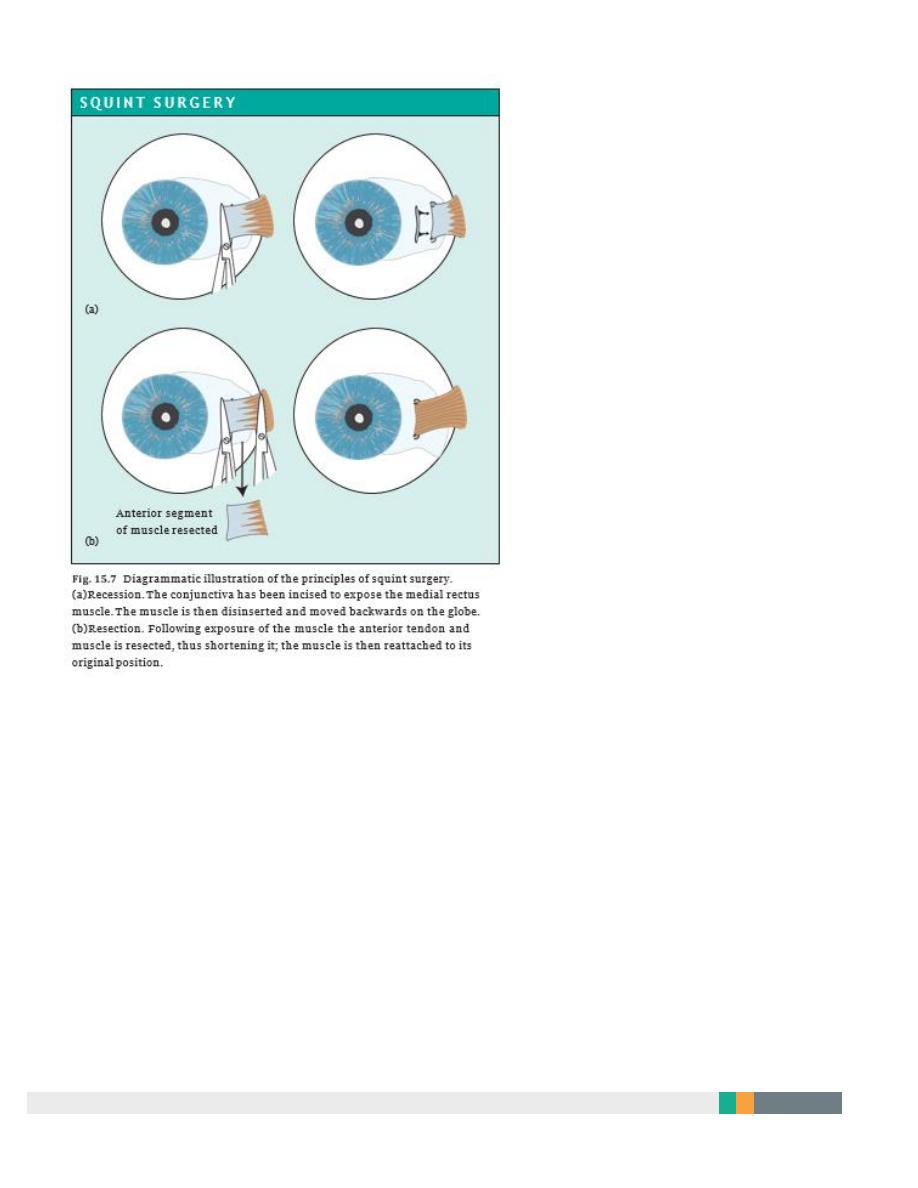

• Surgical intervention to realign the eyes may be required for functional reasons (to

restore or establish binocular single vision) or for cosmetic reasons (to prevent a child

being singled out at school) (Fig. 15.7).

The principle of surgery is to realign the eyes by adjusting the position of the muscles on the

globe or by shortening the muscle. Access to the muscles is gained by making a small incision

in the conjunctiva.

• Moving the muscle insertion backwards on the globe (recession) weakens the muscle.

• Removing a segment of the muscle (resection) strengthens the action.

11

12

13

14

D I S E A S E OF THE E X T R A O C U L A R M U S C L E S

1. Dysthyroid eye disease

PATHOGENESIS

infiltration of the extraocular muscles with lymphocytes and the deposition of

glycosaminoglycans.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

The patient may sometimes complain of:

•

A red painful eye (associated with exposure caused by proptosis

•

Double vision.

•

Reduced visual acuity (sometimes associated with optic neuropathy). On

examination:

•

There may be proptosis of the eye (the eye protrudes from the orbit, also

termed exophthalmos).

•

The eye may be chemosed and injected over the muscle insertions.

•

The upper lid may be retracted

•

The upper lid may lag behind the movement of the globe on downgaze (lid

lag).

•

There may be restricted eye movements or squint (also termed restrictive

thyroid myopathy,

The inferior rectus is the most commonly affected muscle. Involvement of the medial

rectus causes mechanical limitation of abduction thereby mimicking a sixth nerve

palsy.

15

A CT or MRI scan shows enlargement of the muscles.

Dysthyroid eye disease is associated with

two serious acute complications:

1- Exposure keratopathy, and corneal ulcers due to proptosis and failure of the lids

to protect the cornea. The condition may lead to corneal perforation.

2 Compressive optic neuropathy due to compression and ischaemia of the optic

nerve by the thickened muscles. This leads to field loss and may cause blindness.

2. Myasthenia gravis

PATHOGENESIS

development of antibodies to the acetylcholine receptors of striated muscle. It affects

females more than males and although commonest in the 15–50 age group may affect

young children and older adults. Some 40% of patients may show involvement of

the extraocular muscles only.

16

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

The extraocular muscles fatigue resulting in a variable diplopia.

A variable ptosis may also be present.This can be demonstrated by asking the

patient to look up and down rapidly a number of times to fatigue the muscle.

There may be evidence of systemic muscle weakness.

TREATMENT

The diagnosis can be confirmed by electromyography or by

determining whether an injection of neostigmine or edrophonium (cholinesterase

antagonists) temporarily restores normal muscle movement.

This test must be performed under close medical supervision with resuscitation

equipment and atropine to hand because of the possibility of cholinergic side effects

such as bradycardia and bronchospasm.

Patients are treated, in collaboration with a neurologist, with neostigmine or

pyridostigmine.

Systemic steroids and surgical removal of the thymus also have a role in treatment.

Ocular myositis

This is an inflammation of the extraocular muscles associated with pain ,diplopia,

and restriction in the movement of the involved muscle (similar to that seen in

dysthyroid eye disease).

It is not usually associated with systemic disease but thyroid abnormalities should

be excluded. The conjunctiva over the involved muscle is inflamed.

CT or MRI scanning shows a thickening of the muscle.

If symptoms are troublesome it responds to a short course of steroids.

17

Ocular myopathy

Ocular myopathy (progressive external ophthalmoplegia) is a rare condition where

the movement of the eyes is slowly and symmetrically reduced. There is an

associated ptosis. Ultimately, eye movement may be lost completely.

Brown’s syndrome

The action of the superior oblique muscle may be restricted which reduces elevation

of the eye when it is adducted (Brown’s syndrome). Usually congenital but may be

traumatic or inflammatory.

Duane’s syndrome

This is a ‘congenital miswiring’ of the medial and lateral rectus muscles There is

neuromuscular activity in the lateral rectus during adduction and reduced lateral

rectus activity in abduction. This results in limited abduction , and apparent

narrowing of the palpebral aperture on adduction with retraction of the eye into the

globe (due to contraction of both medial and lateral rectus muscles). The condition

may be unilateral or, more rarely, bilateral.

18

ABNORMAL OSCILLATIONS OF THE EYES

Nystagmus

Repeated involuntary to and fro or up and down oscillations of the eyes.

Either Jerk (fast & slow phases) or Pendular

Either Physiological or Pathological

A. Physiological Nystagmus:

1-when following a moving object (e.g. looking out of a train window) (optokinetic

nystagmus)

2- following stimulation of the vestibular system (Vestibular nystagmus).

3- Jerk nystagmus may also be seen at the extreme position of gaze (end gaze

nystagmus

B. Pathological Nystagmus

1 ACQUIRED NYSTAGMUS

Pathologically, jerk nystagmus may be seen:

•

In cerebellar disease,.

•

With some drugs (such as barbiturates).

•

In damage to the labyrinth and its central connections

•

An upbeat nystagmus (fast phase upwards) is commonly associated with

brainstem disease. It may also be seen in toxic states, e.g. with excess alcohol

intake.

19

•

A downbeat nystagmus may be seen in patients with a posterior fossa lesion

near the cervicomedullary junction It may also be seen in patients with

demyelination and again may be present in toxic states.

•

(gaze-evoked nystagmus). In Patients with nerve palsies or weakness of the

extraocular muscles may develop nystagmus when looking in the direction of

the affected muscle

2 CONGENITAL NYSTAGMUS

Nystagmus can be congenital in origin.

•

Sensory congenital nystagmus. (pendular or jerk variety. It is associated with

poor vision (e.g. congenital cataract, albinism).

•

Motor congenital nystagmus is a jerk nystagmus developing at birth in

children with no visual defect.

A.L.Y