The sleep apnoea/hypopnoea

syndrome

Definition

• OSAHS is defined on the basis of nocturnal and daytime symptoms as well

as sleep study findings.

• Diagnosis requires the patient to have :

(1) either symptoms of nocturnal breathing disturbances (snoring, gasping,

or breathing pauses during sleep) or daytime sleepiness or fatigue that

occurs despite sufficient opportunities to sleep and is unexplained by other

medical problems.

(2) five or more episodes of obstructive apnea or hypopnea per hour

of sleep (the apnea-hypopnea index [AHI]) documented during a sleep study.

(3) OSAHS also may be diagnosed in the absence of symptoms if the AHI is

above 15.

• 2–4% of the middle-aged population suffer from recurrent upper

airway obstruction during sleep.

• The resulting sleep fragmentation causes daytime sleepiness,

especially in monotonous situations, resulting in a threefold increased

risk of road traffic accidents and a ninefold increased risk of single-

vehicle accidents

Aetiology

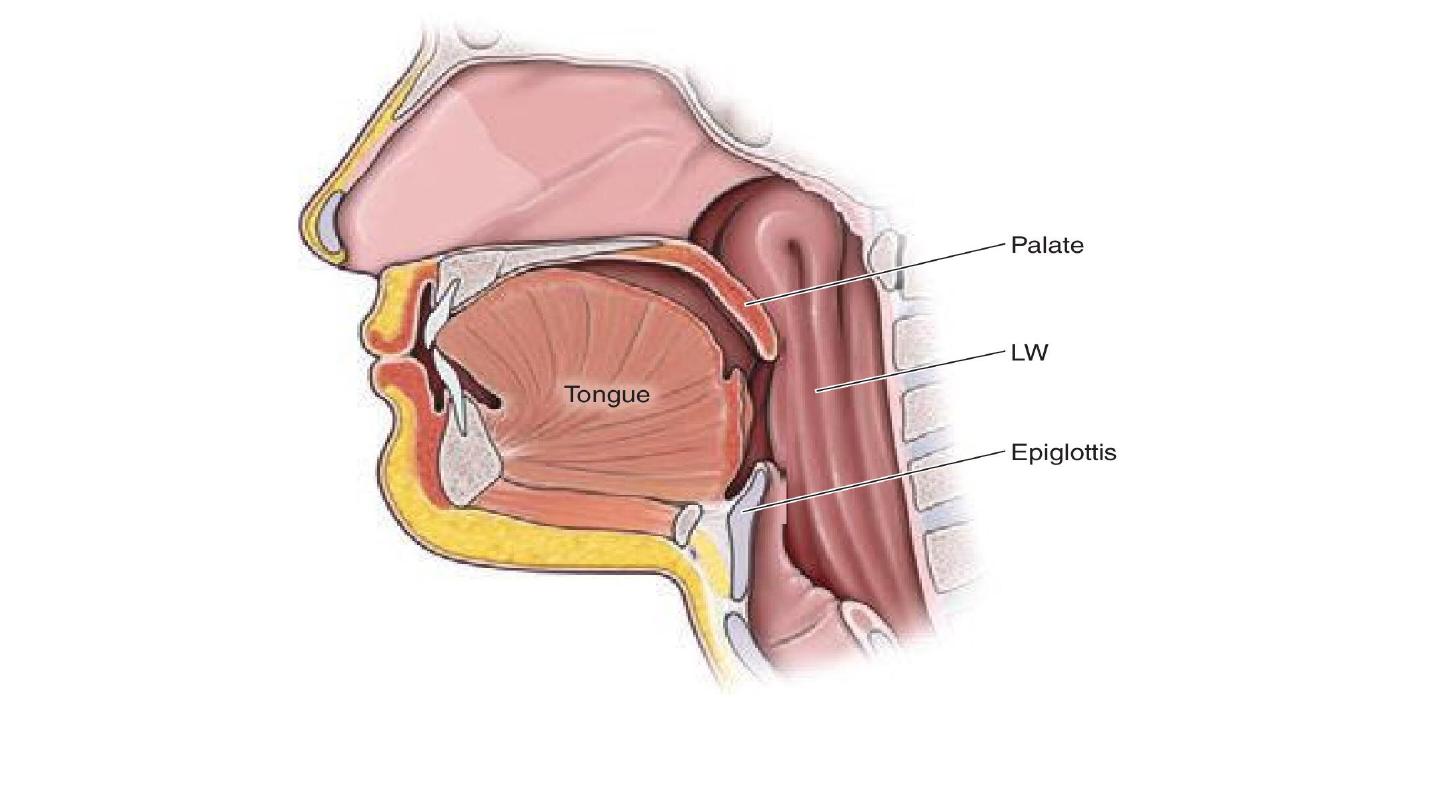

• Recurrent occlusion of the pharynx during sleep, usually at the level

of the soft palate.

• During wakefulness, upper airway dilating muscles, contract actively

during inspiration to preserve airway patency. During sleep, muscle

tone declines, impairing the ability of these muscles to maintain

pharyngeal patency.

• In a minority of people, a combination of an anatomically narrow

palatopharynx and underactivity of the dilating muscles during sleep

results in inspiratory airway obstruction.

• Incomplete obstruction causes turbulent flow, resulting in snoring (around

40% of middle-aged men and 20% of middle-aged women snore).

• More severe obstruction triggers increased inspiratory effort and transiently

wakes the patient, allowing the dilating muscles to re-open the airway.

These awakenings are so brief.

• After a series of loud deep breaths that may wake their bed partner, the

patient rapidly returns to sleep, snores and becomes apnoeic once more.

• This cycle of apnoea and awakening may repeat itself many hundreds of

times per night and results in severe sleep fragmentation and secondary

variations in blood pressure, which may predispose over time to

cardiovascular disease.

• As a result, sleep-disordered breathing is associated over time with

sustained hypertension and an increased risk of coronary events and

stroke.

• An association has also been described with insulin resistance, the

metabolic syndrome and type II diabetes.

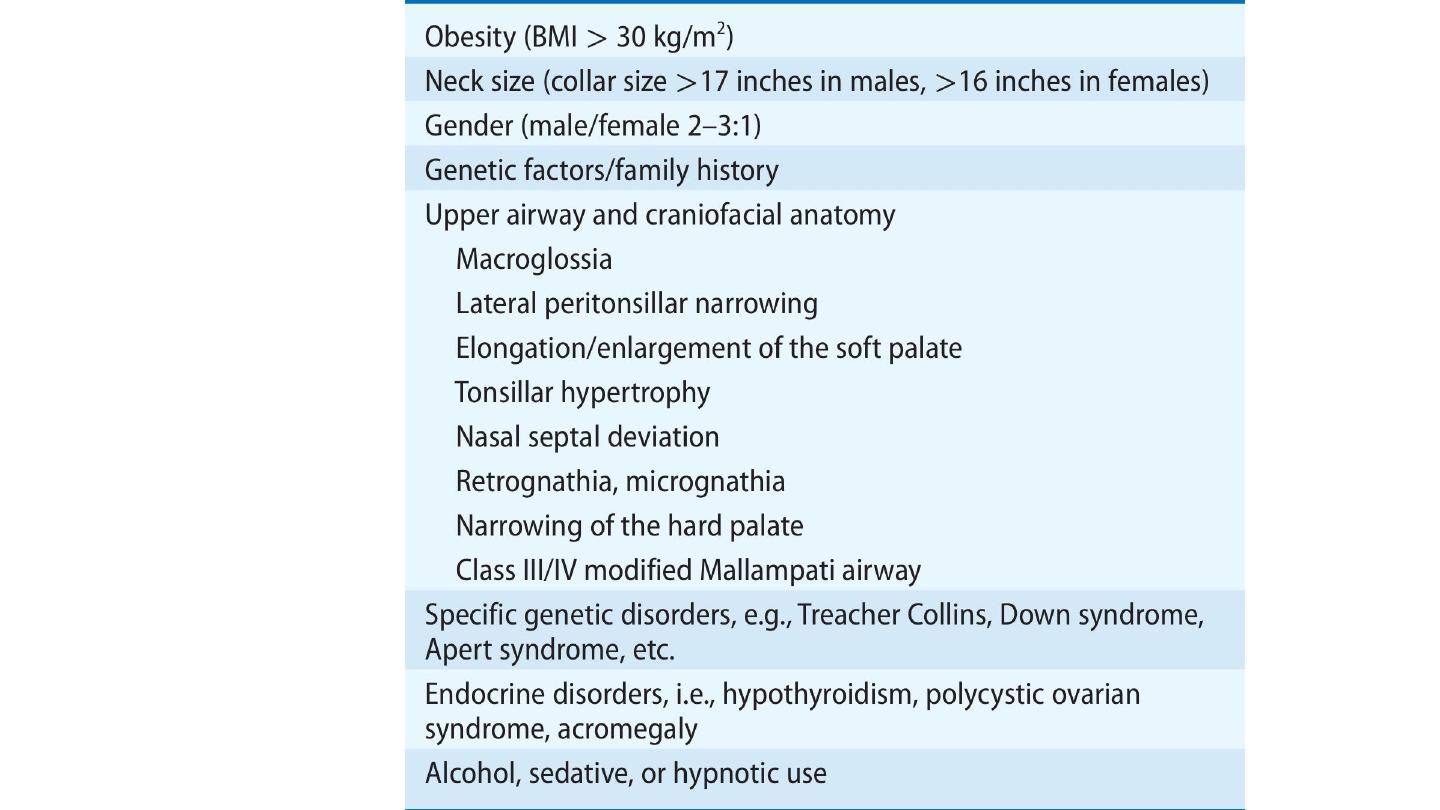

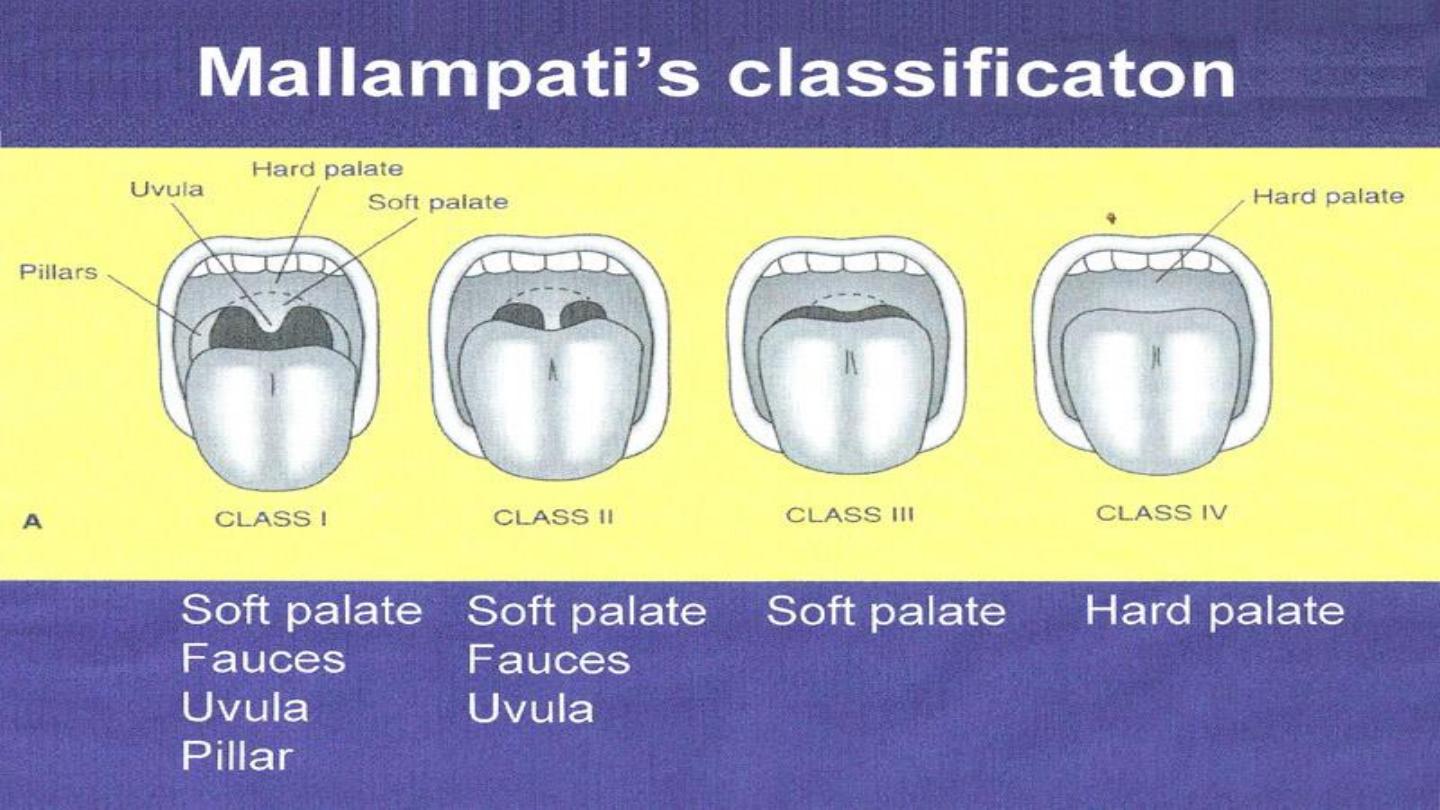

• Risk Factors for

Obstructive

Sleep Apnea

Clinical features

• Excessive daytime sleepiness

• Snoring

• Unrefreshed sleep

• Bed partners report loud snoring in all body positions and often have

noticed multiple breathing pauses (apnoeas).

• Difficulty with concentration, impaired cognitive function and work

performance, depression, irritability and nocturia are other features

Common sites of airway collapse. For example, the palate, tongue, and/or epiglottis (Ep) can

be displaced, and the lateral pharyngeal walls (LW) can collapse

Investigations

Those who should be referred for sleep assessment:

• anyone who repeatedly falls asleep during the day when not in bed

• who complains that his or her work is impaired by sleepiness

• who is a habitual snorer with multiple witnessed apnoeas

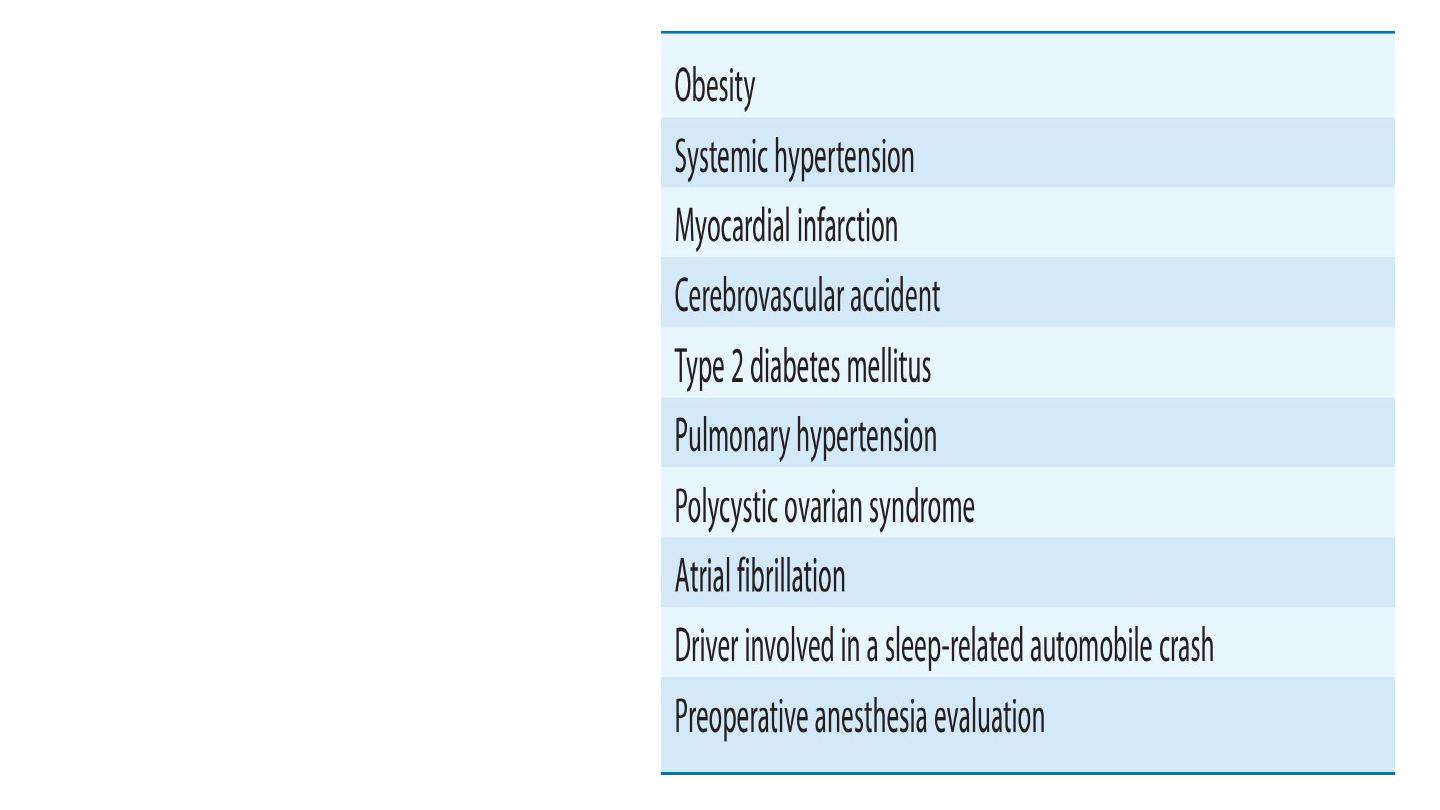

Conditions

in

which

Evaluation for Obstructive

Sleep Apnea Should be

Considered

• Mild OSAHS: AHI of 5–14 events/h

• Moderate OSAHS: AHI of 15–29 events/h

• Severe OSAHS: AHI of ≥30 events/h

• Apnea: Cessation of airflow for ≥10 sec during sleep

• Hypopnea: A ≥30% reduction in airflow for at least 10 sec during

sleep that is accompanied by either a ≥3% desaturation or an arousal

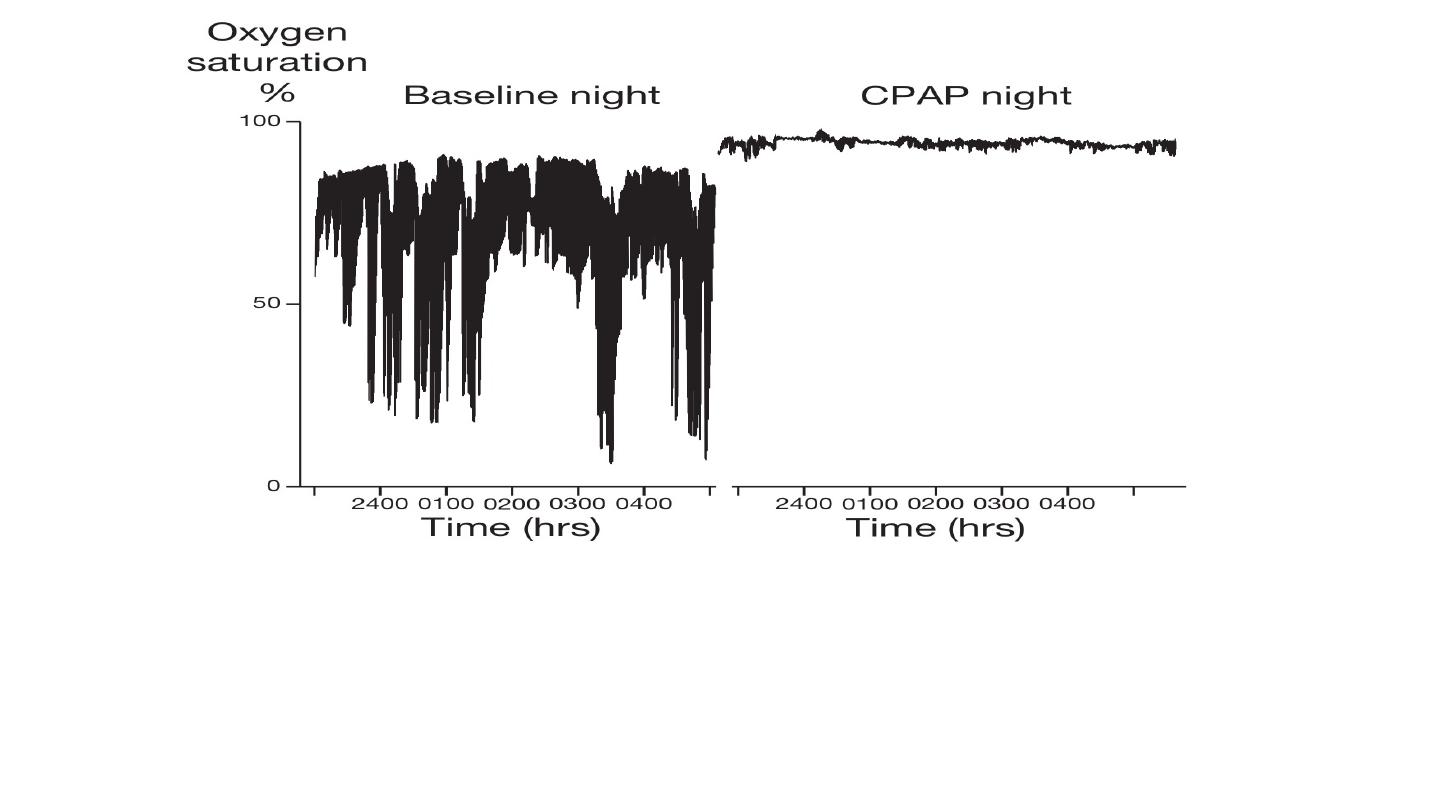

Sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome: overnight oxygen saturation trace

The left-hand panel shows the trace of a patient who had 53 apnoeas plus hypopnoeas/hour, 55 brief

awakenings/hour and marked oxygen desaturation.

The right-hand panel shows the effect of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) of 10 cm H2O delivered

through a tight-fitting nasal mask: it abolished his breathing irregularity and awakenings, and improved

oxygenation.

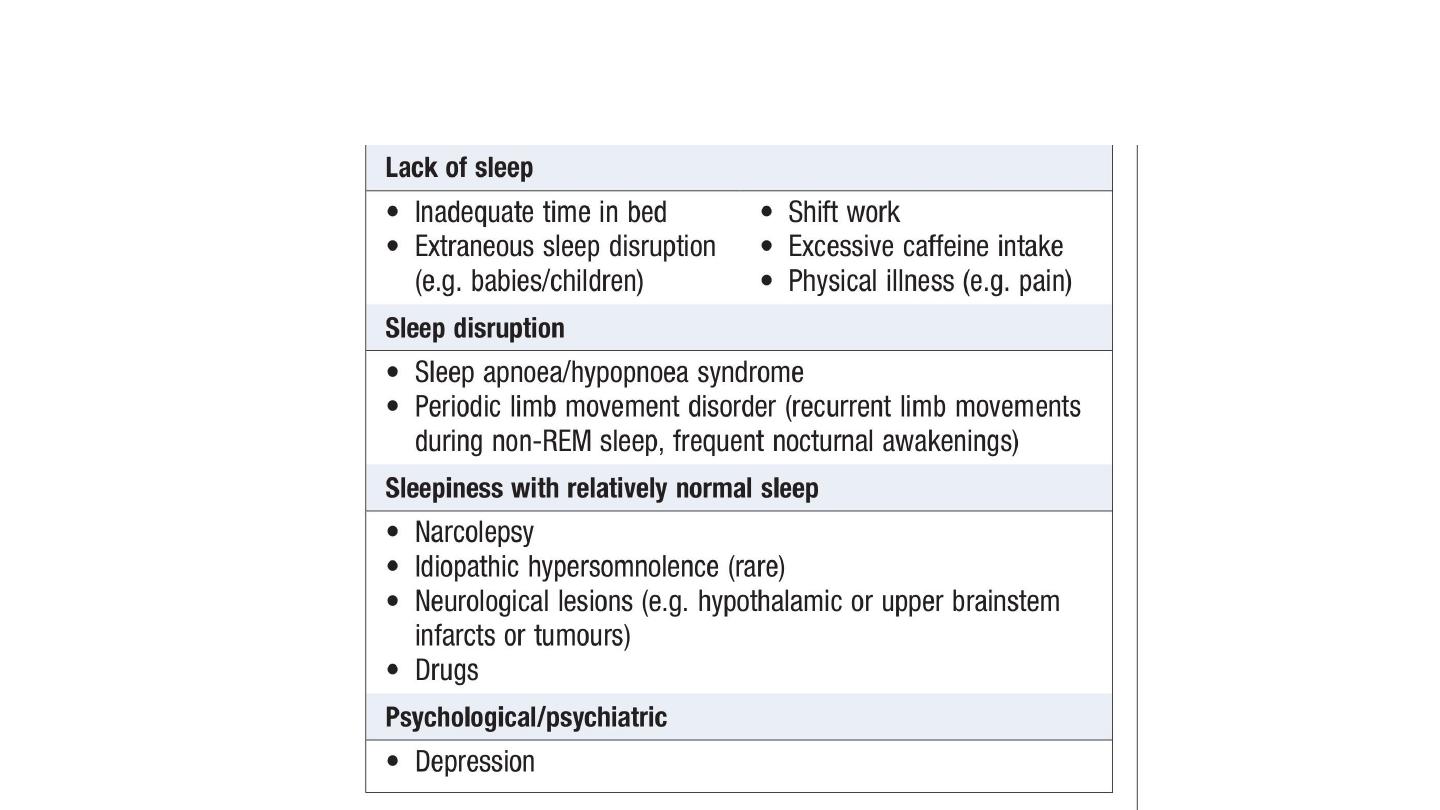

Differential diagnosis of persistent sleepiness

Management

• All drivers must be advised not to drive until treatment has relieved

their sleepiness.

• Relief of nasal obstruction or the avoidance of alcohol may prevent

obstruction.

• Advice to obese patients to lose weight

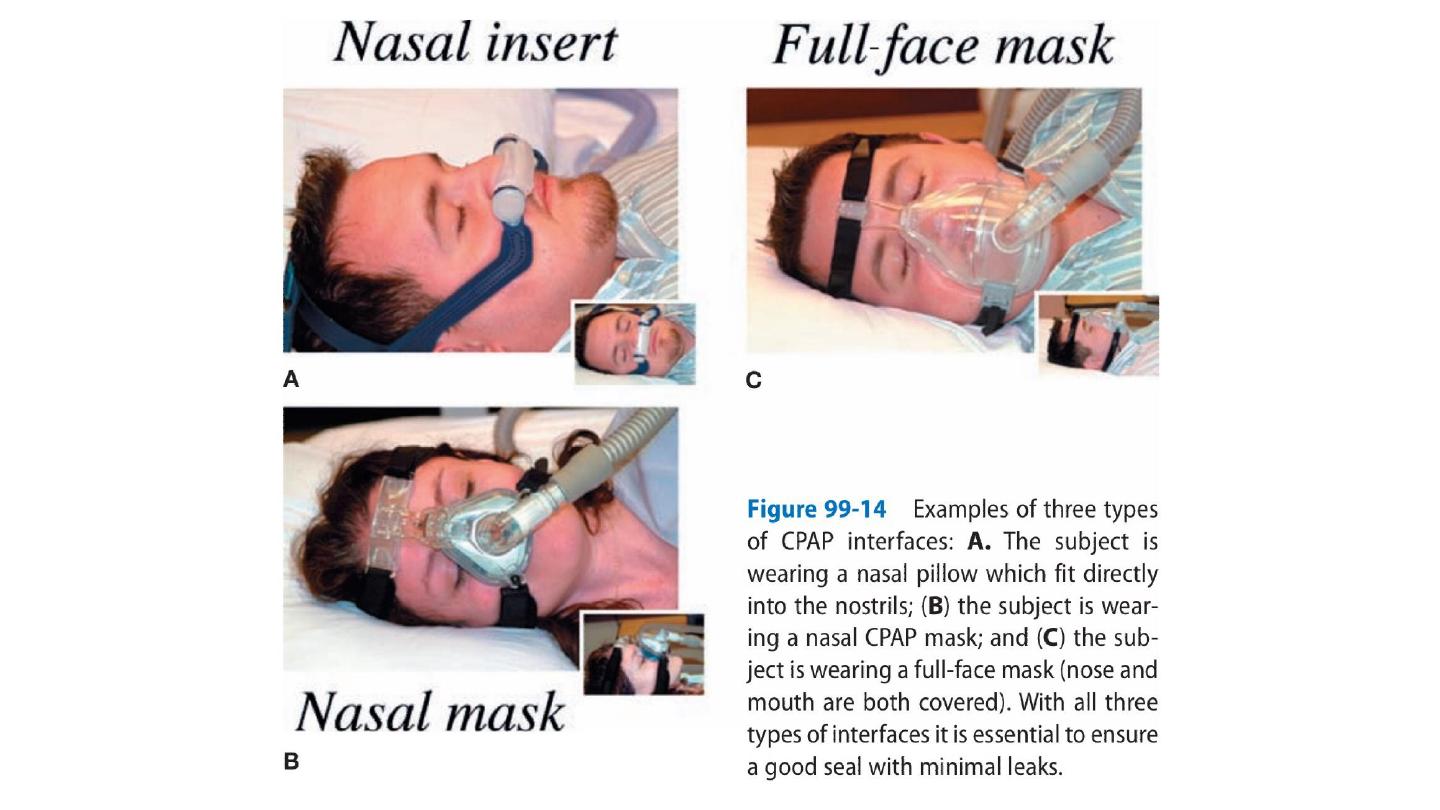

• The majority of patients need to use continuous positive airway

pressure (CPAP) delivered by a nasal mask every night to splint the

upper airway open.

• Unfortunately, 30–50% of patients do not tolerate CPAP.

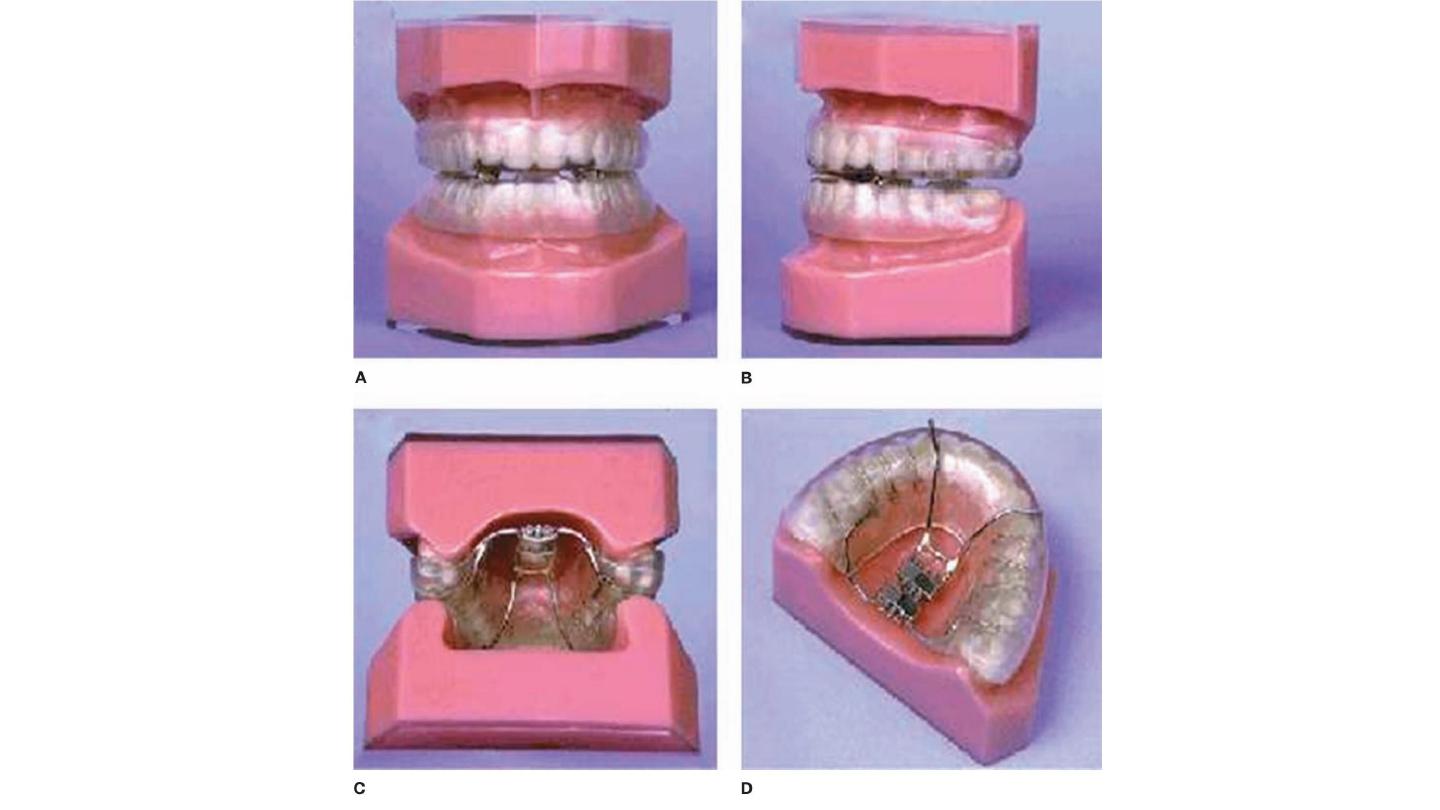

• Mandibular advancement devices.

• There is no evidence that palatal surgery is of benefit.

CENTRAL SLEEP APNEA

• CSA, which is less common than OSAHS, may occur in isolation or,

more often, in combination with obstructive events in the form of

“mixed” apneas.

• CSA is often caused by an increased sensitivity to pCO2, which leads

to an unstable breathing pattern that manifests as hyperventilation

alternating with apnea.

Risk Factors

• congestive heart failure

• opioid medications

• hypoxia (e.g., breathing at high altitude)

• In some individuals, CPAP—particularly at high pressures—seems to

induce central apnea

• CSA may be caused by blunted chemosensitivity due to congenital

disorders (congenital central hypoventilation syndrome) or acquired

factors.

• Treatment of CSA is difficult and depends on the underlying cause.