Color Atlas of Veterinary

Histopathology

By

Hafidh I. AL- Sadi

BVMS, University of Mosul - Iraq

MS. Pathology, Davis University - USA

Ph.D. Pathology, Davis University - USA

Saevan Saad Al-Mahmood

BVMS, University of Mosul - Iraq

M.Sc. Pathology, University of Mosul - Iraq

Ph.D. Pathology, University of Mosul - Iraq

First edition - 2010

Systemic Pathology (10) : The Respiratory System

54

Systemic Pathology (10)

The Respiratory System

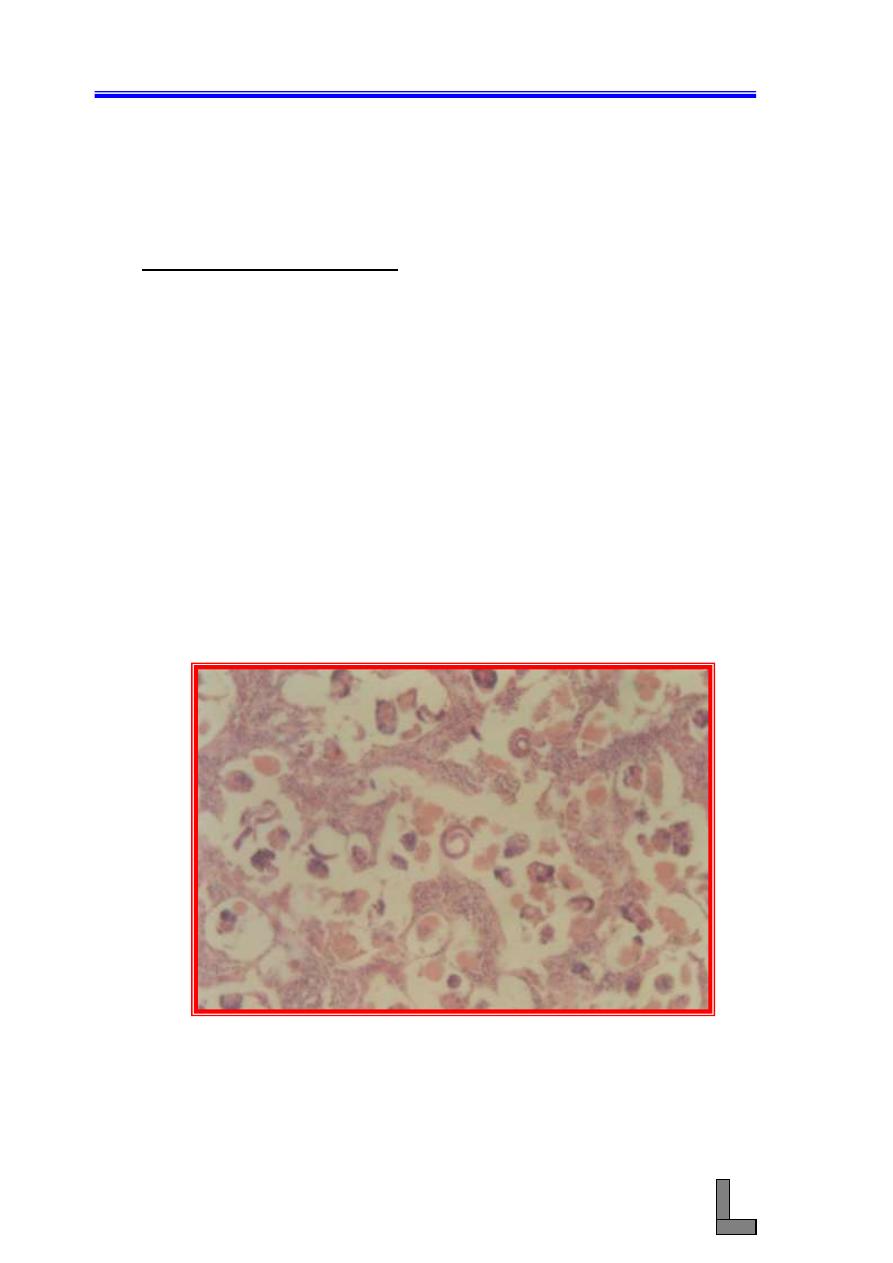

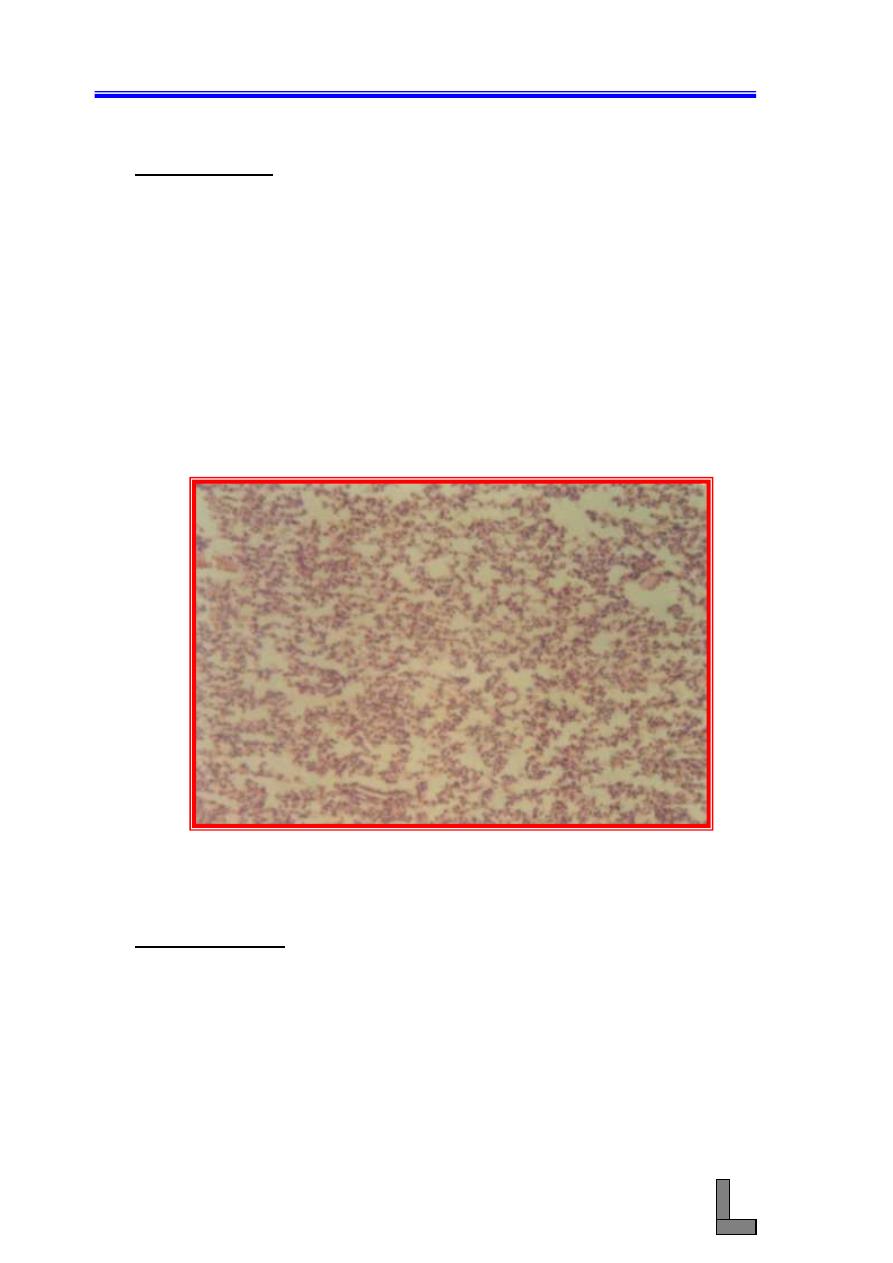

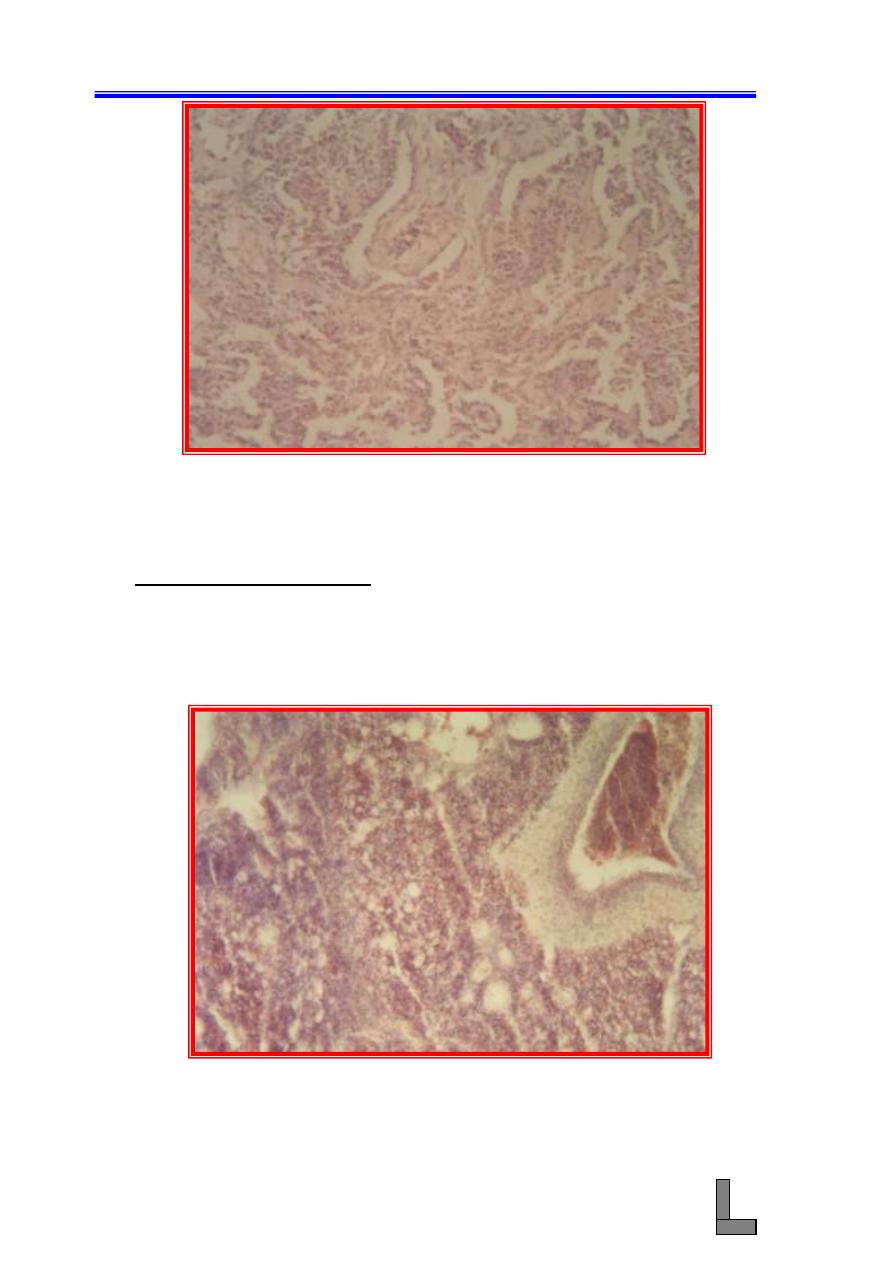

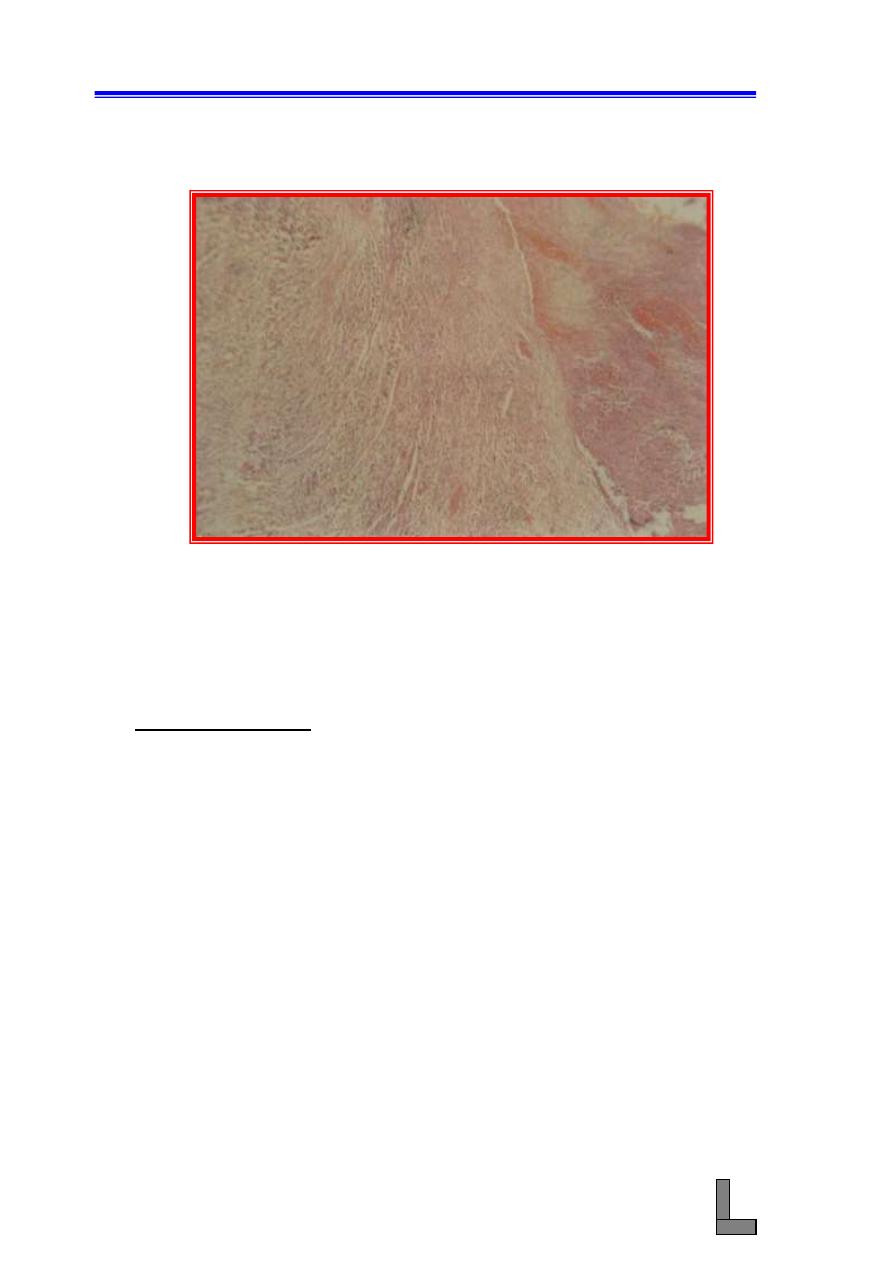

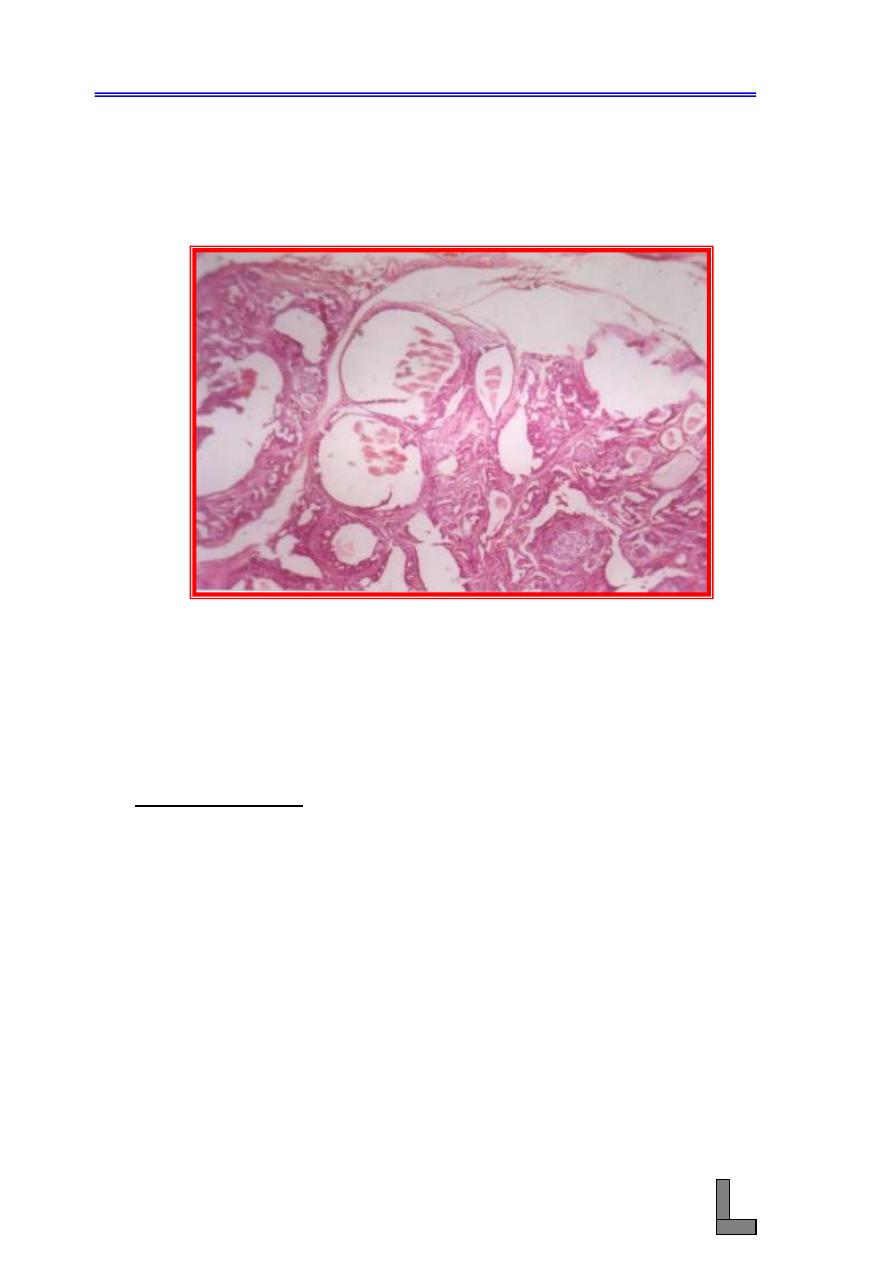

(1) Verminous pneumonia: Also called pulmonary nematodiasis,

lungworm

disease,

Dictyocauliasis,

Dictyocaulosis,

and

Metastrongyloidosis.

Important

parasite

species

include

Dictyocaulus viviparous (cattle, deer, buffalo, camels), D. filaria

(sheep and goats) and D. arnifieldi (horses and donkeys),

Protostrongylus rufescens (sheep and goats), Mullerius capillaris

(sheep and goats).

(A) Note the larvae in the alveoli inciting inflammatory cellular infiltrate

chiefly composed of eosinophils, which fill the alveoli, alveolar

septae, and terminal bronchioles.

(B) Heavy infection is often associated with extensive pulmonary edema

and interstitial emphysema.

(C) The larvae break through the capillary and alveolar walls, they cause

hemorrhage and necrosis.

(D) Remember that when the number of larvae is large, the lesion could

be seen grossly as foci of consolidation randomly distributed

throughout the lungs.

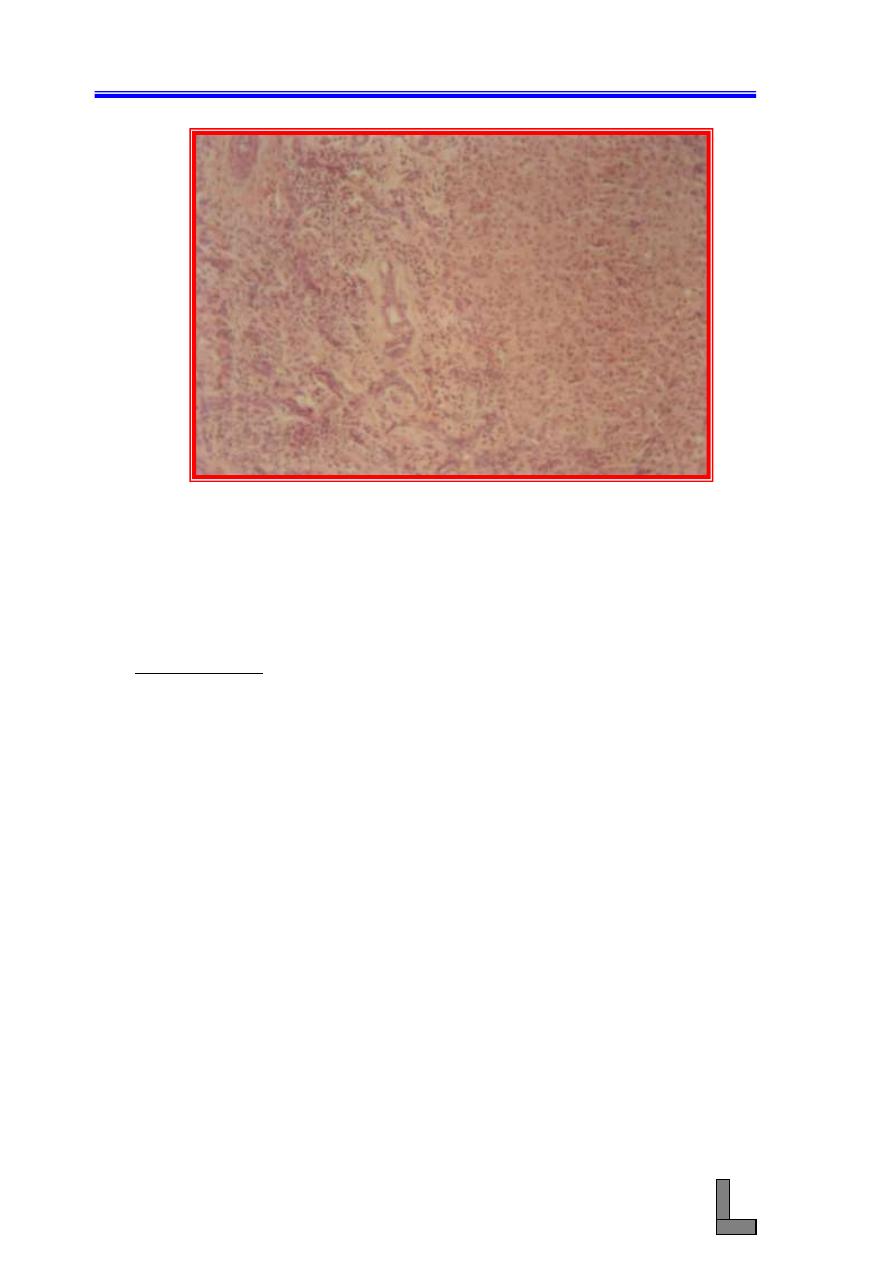

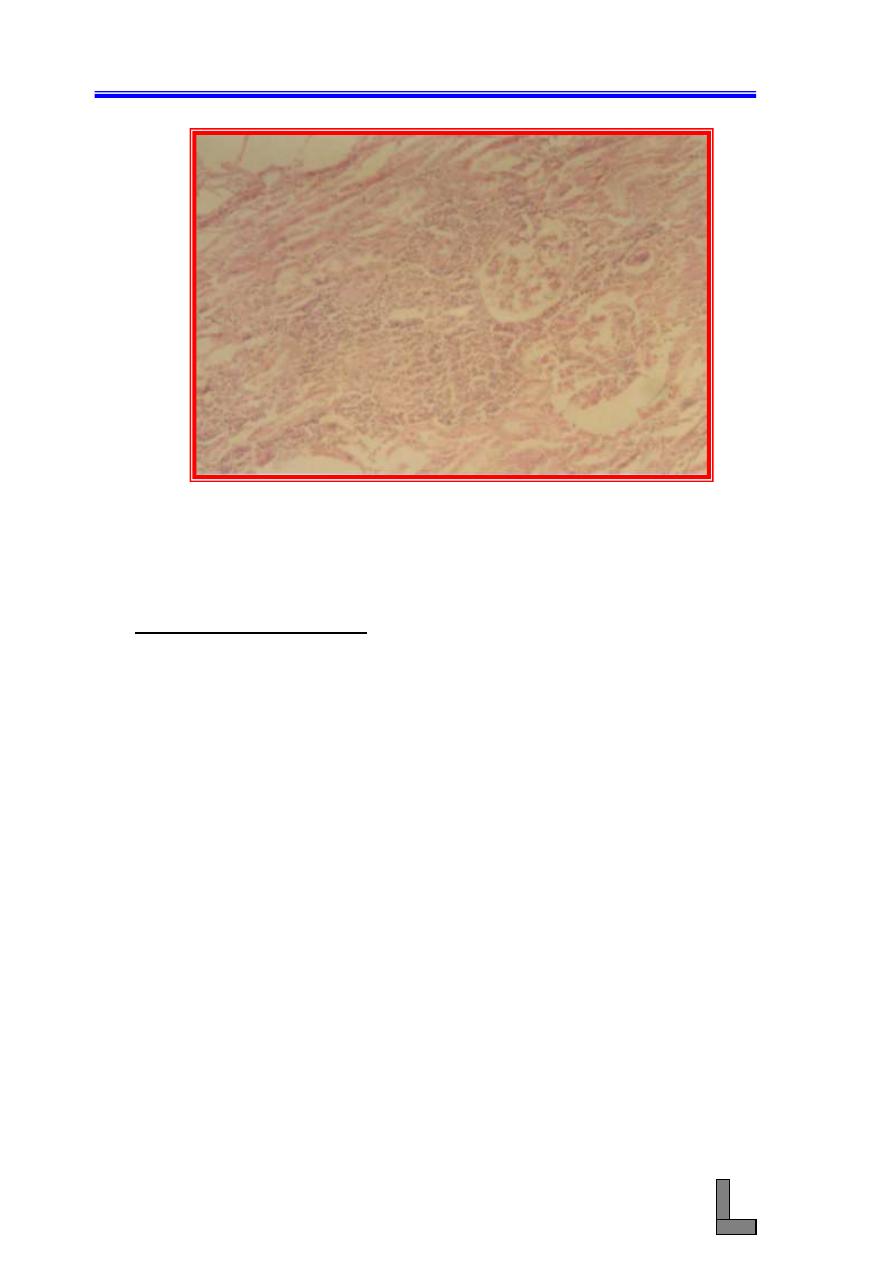

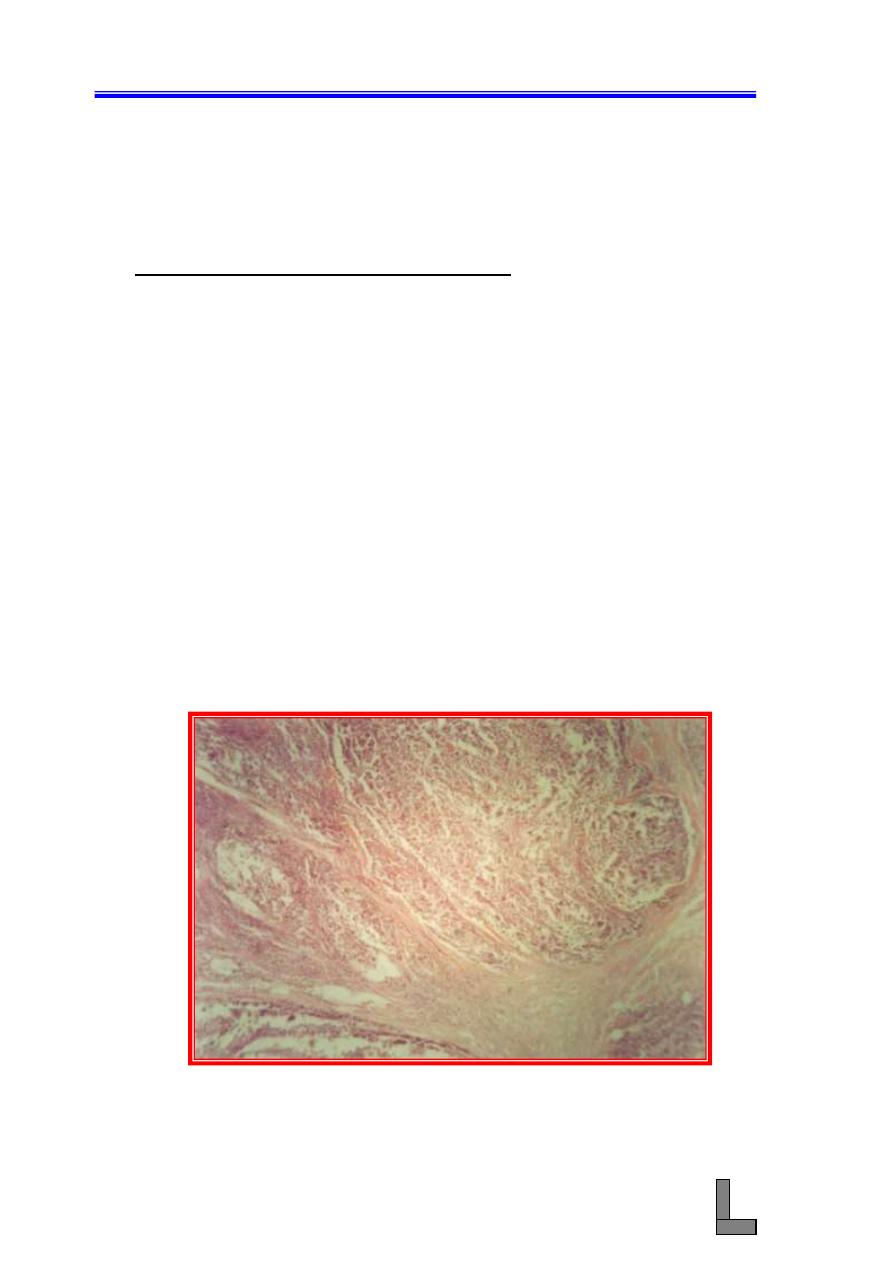

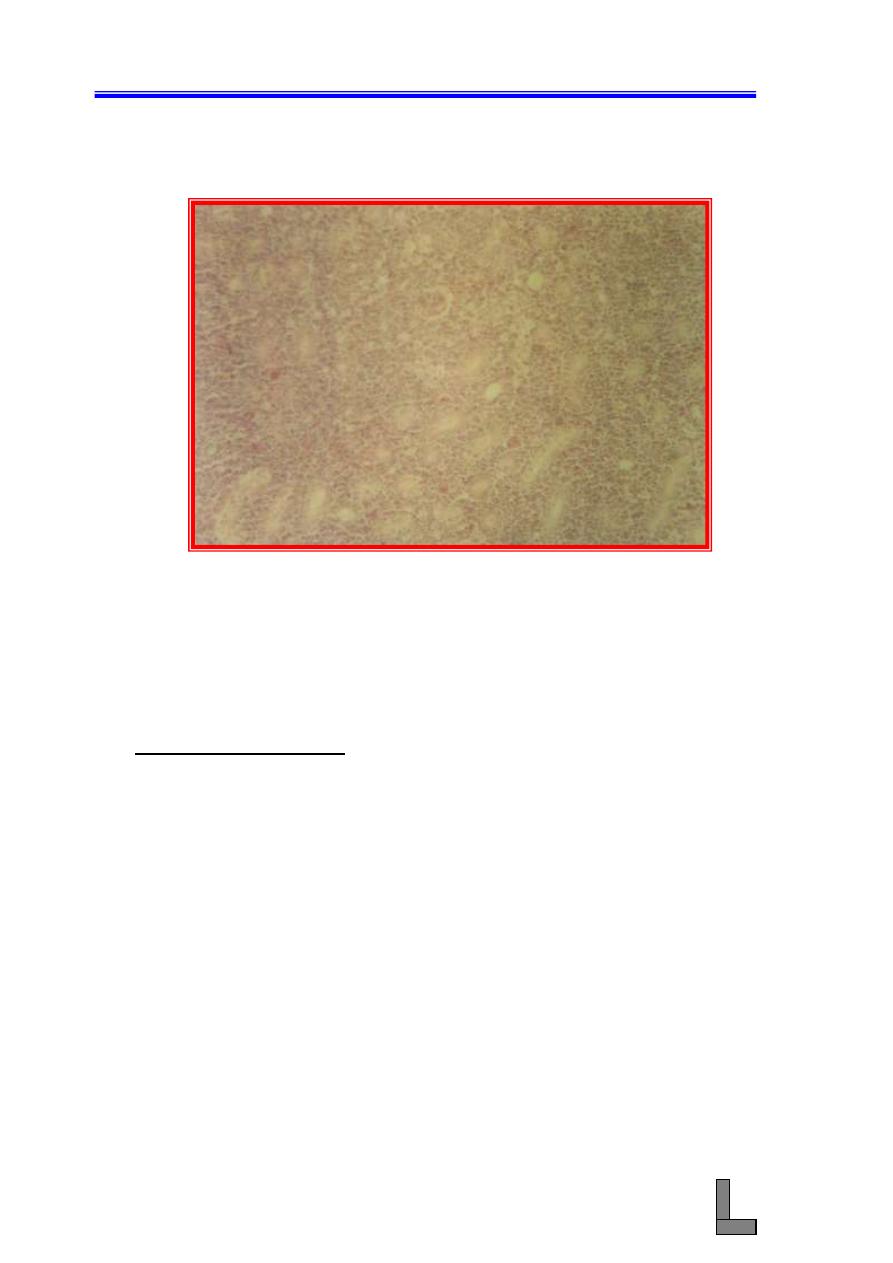

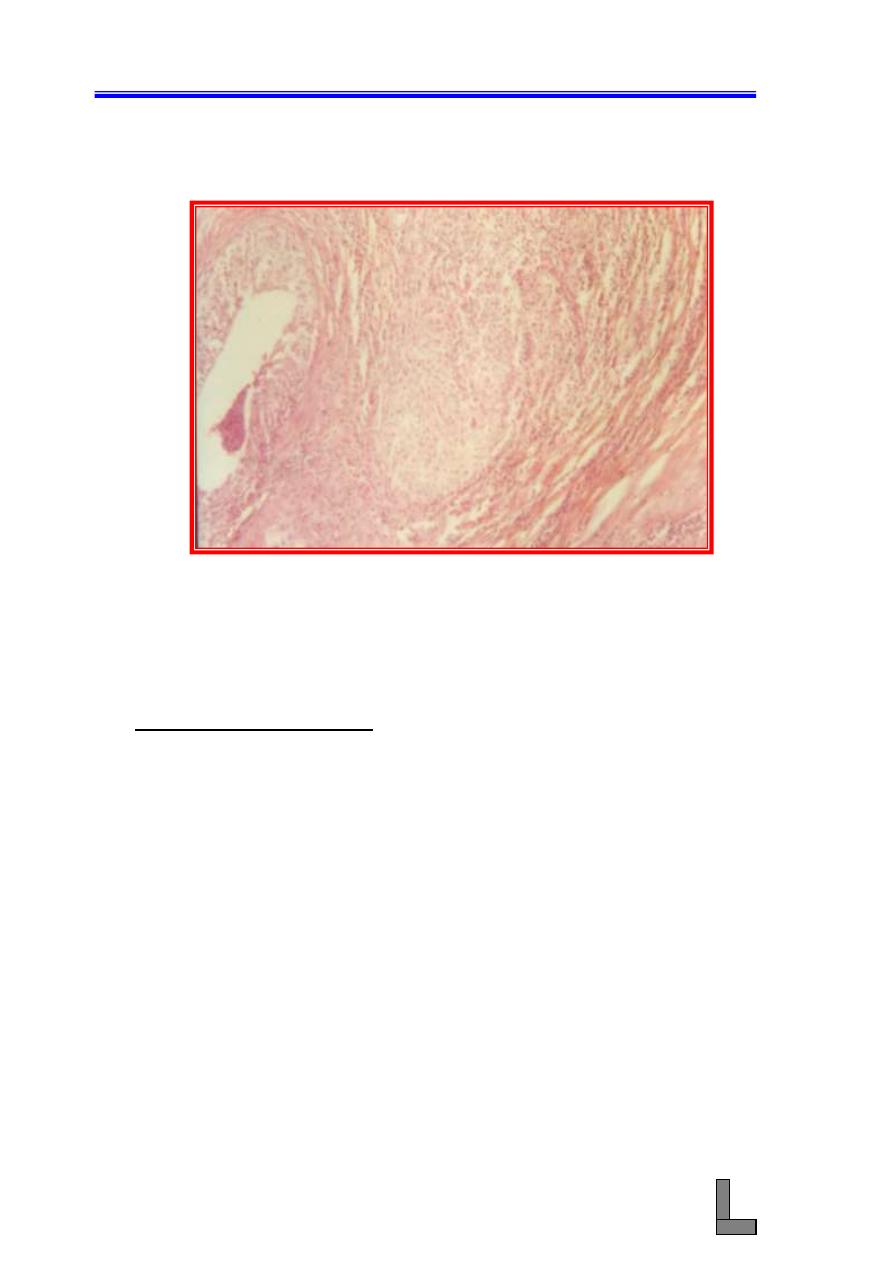

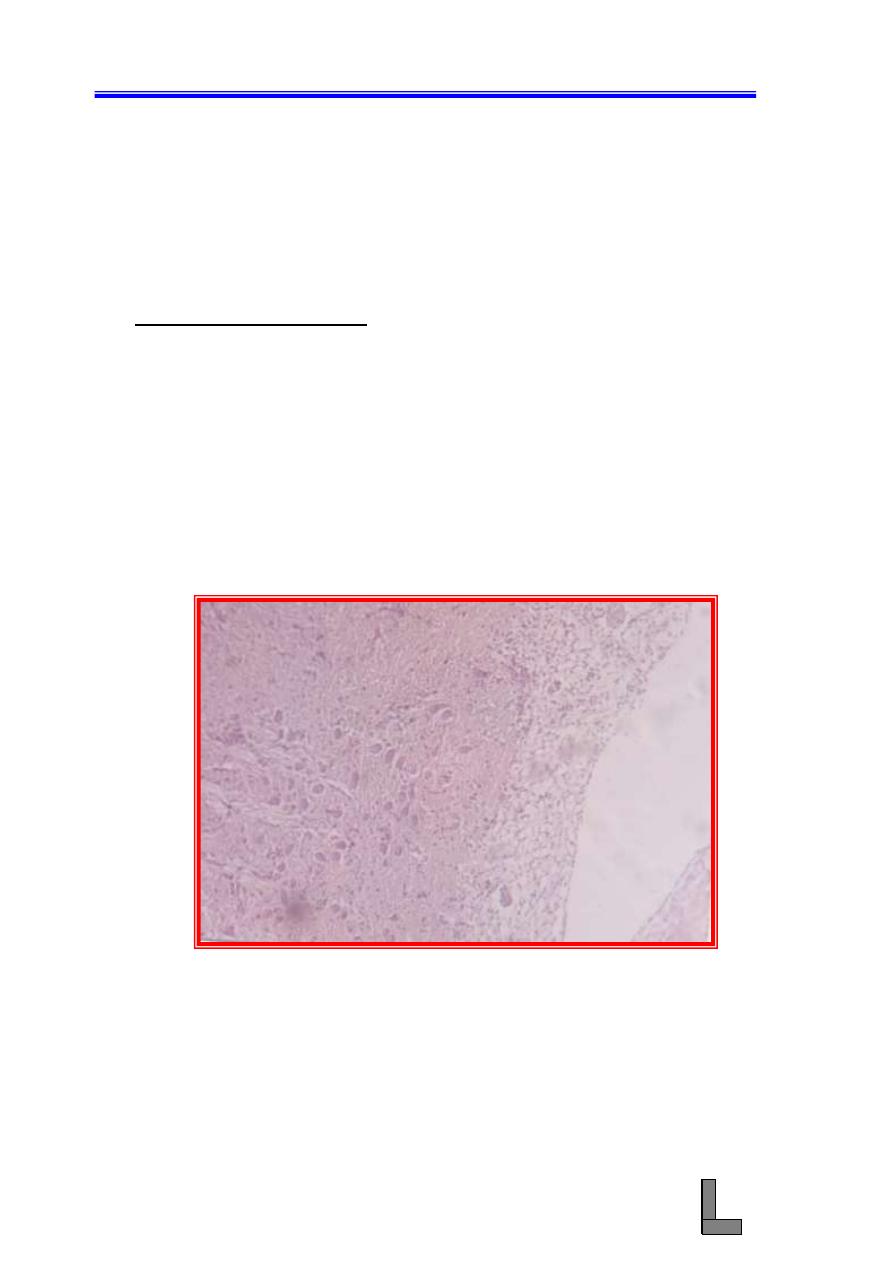

Fig. 41-

Photomicrograph of a lung showing verminous pneumonia.

Note the presence of numerous developmental stages of

lungworms in the alveoli and bronchioles. Emphysema,

edema, and inflammatory exudate could also be seen. H&E

stain. X 100.

Systemic Pathology (10) : The Respiratory System

55

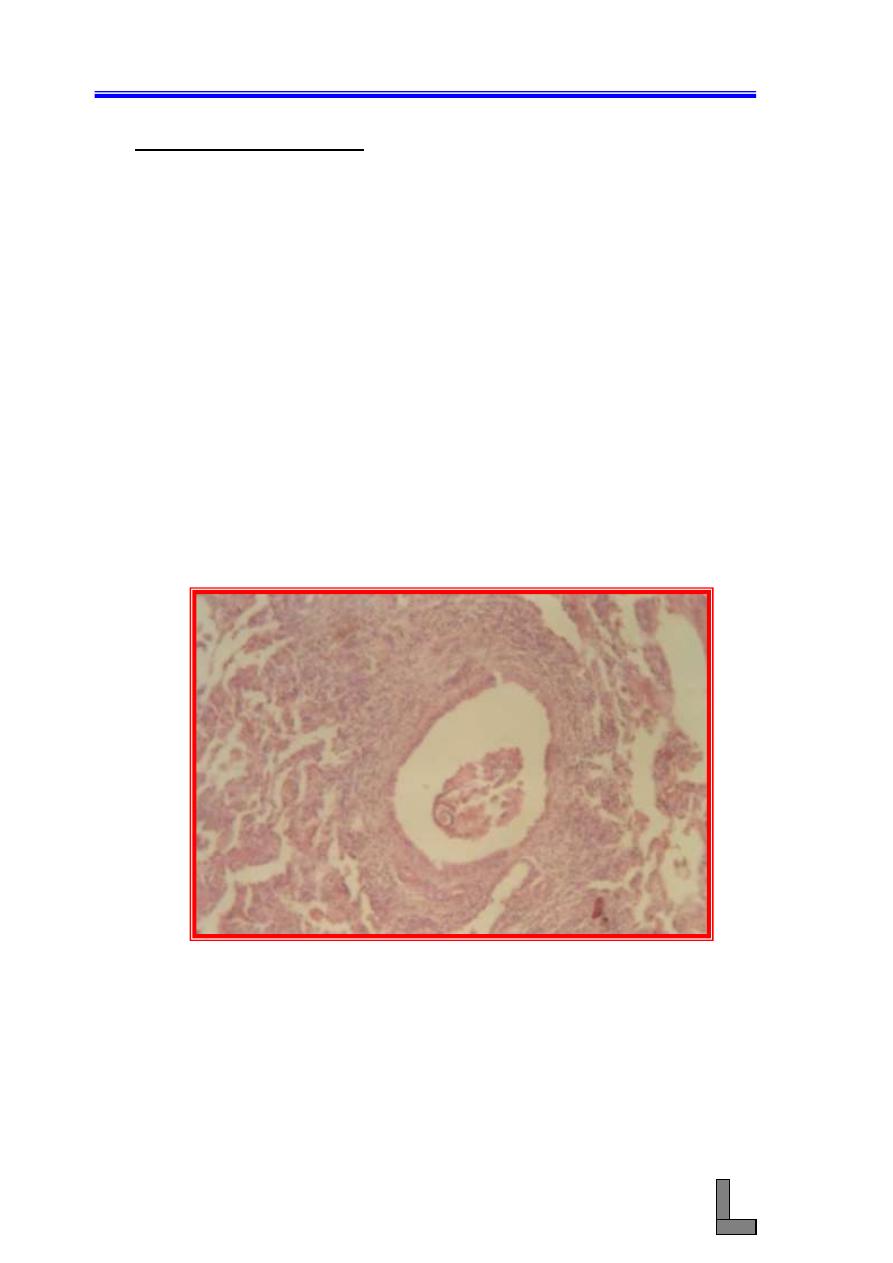

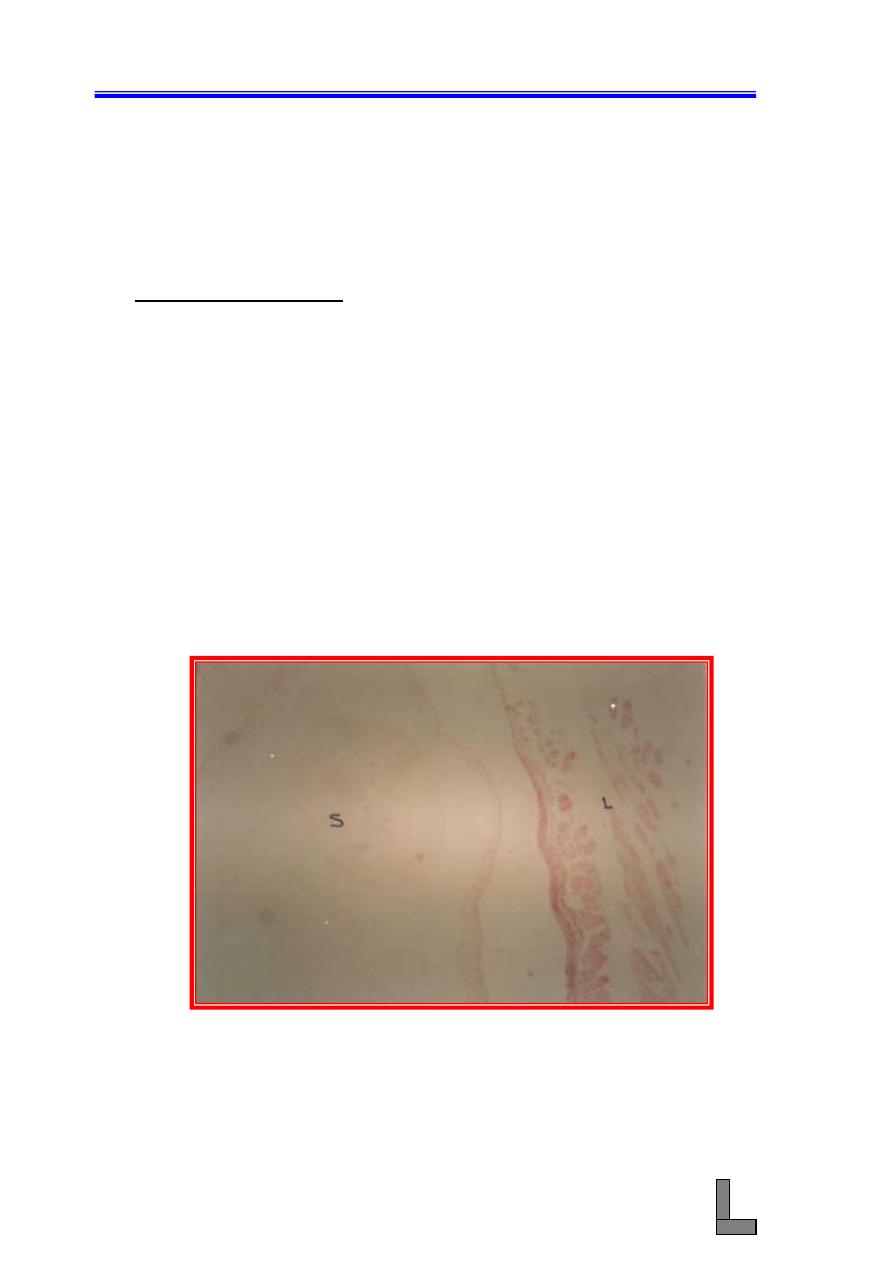

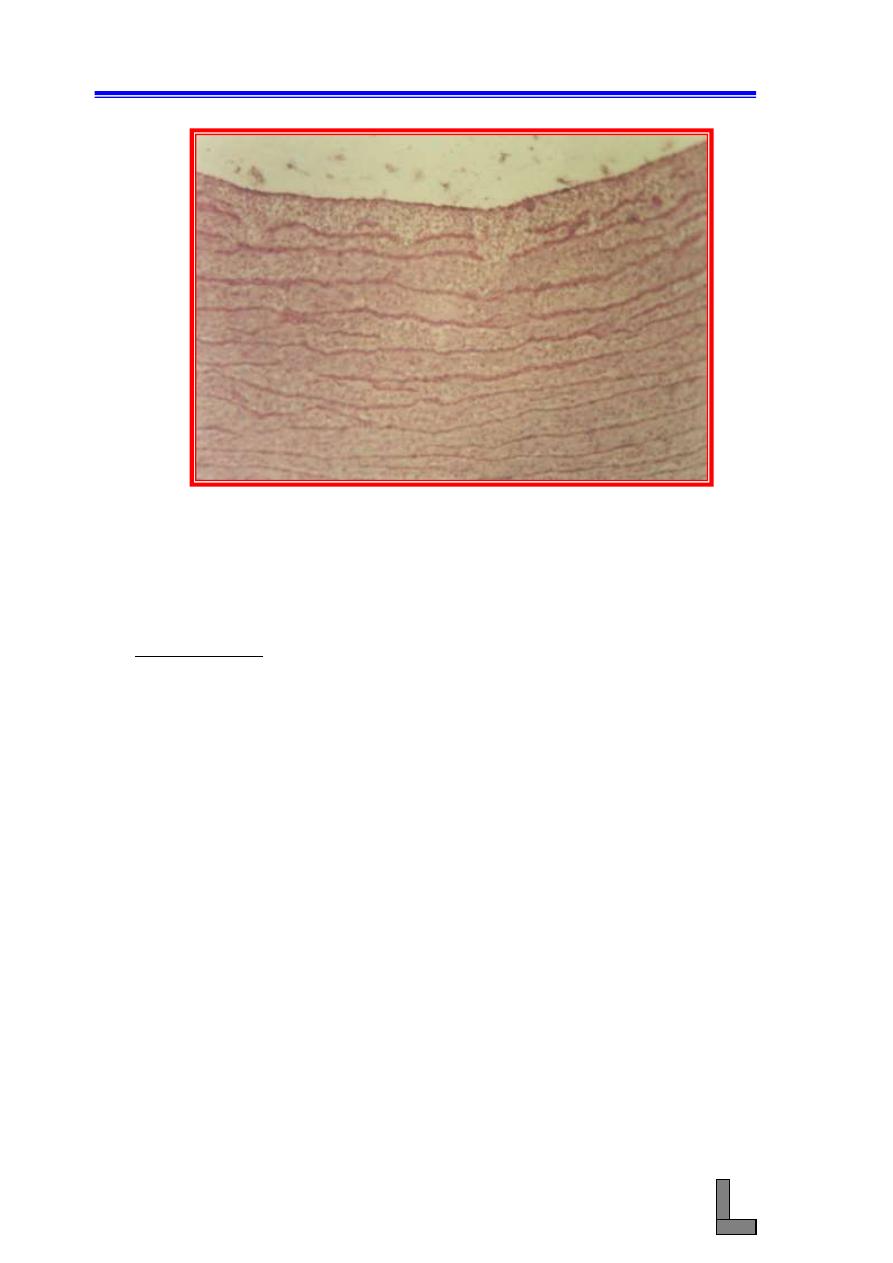

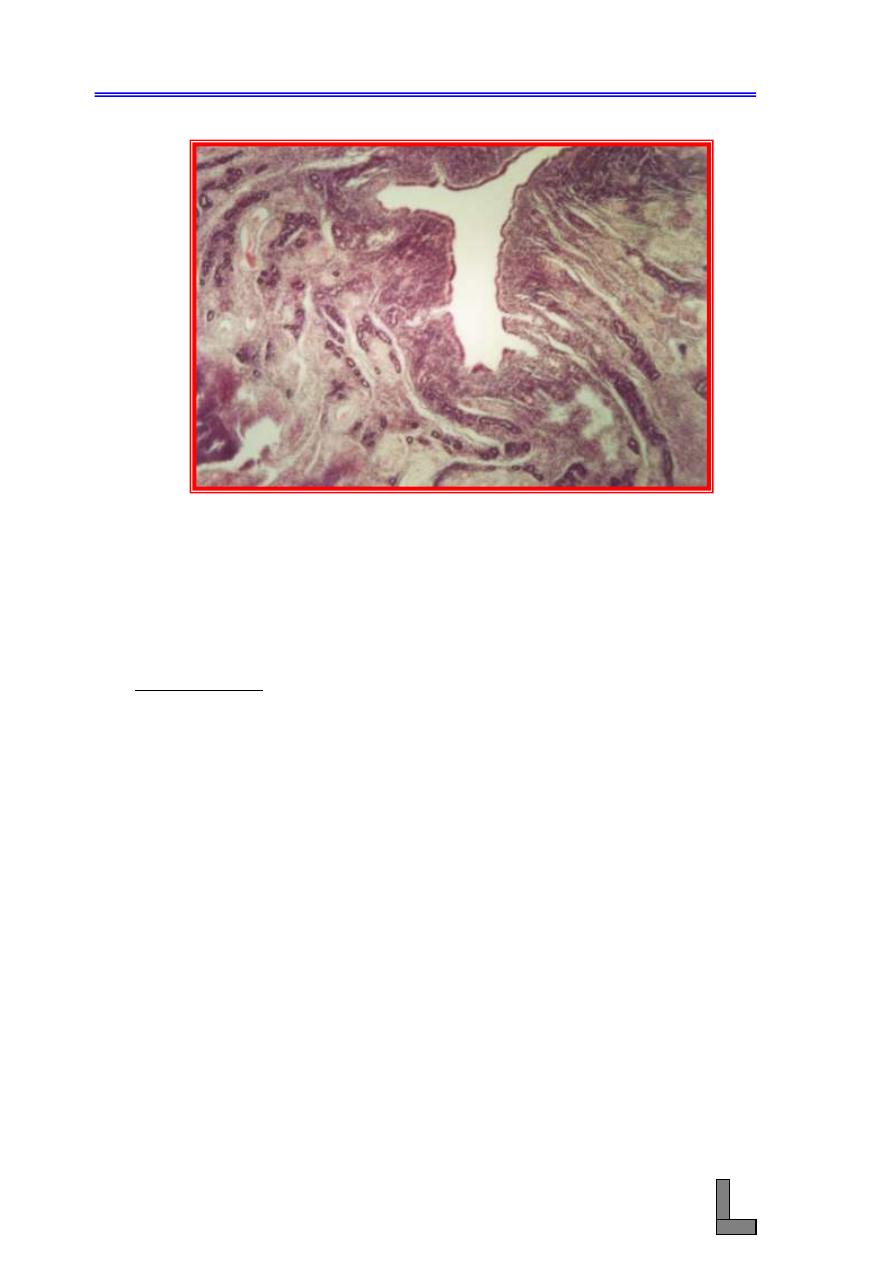

(2) Parasitic bronchitis: See the pervious slide: Adult pulmonary

nematodes reside in the bronchi, where eggs are deposited, some of

which may hatch in the airways. Eggs and / or larvae are coughed

up, swallowed, and passed in the feces, they then develop to

infective 3

rd

stage larvae in the soil. Ingested larvae penetrate the

intestinal mucosa and migrate via lymphatic to mesenteric lymph

nodes, where they develop to 4

th

stage larvae. These reach the lungs

by way of lymphatics and pulmonary arteries. They enter the

pulmonary alveoli, and bronchioles and bronchi, where they reach to

sexual maturity.

(A) The bronchial epithelium is hyperplastic, and eosinophils and

lymphocytes infiltrate the wall and peribronchial tissues.

(B) Eosinophils and mucous plug the bronchial lumens, which when

occluded, lead to atelectasis or consolidation of the related

alveoli.

(C) Adults feed on mucus and cellular detritus, deposit ova; these are

coughed up as embryonated eggs or hatched larvae, or they may

lodge in alveoli, initiating a foreign body reaction.

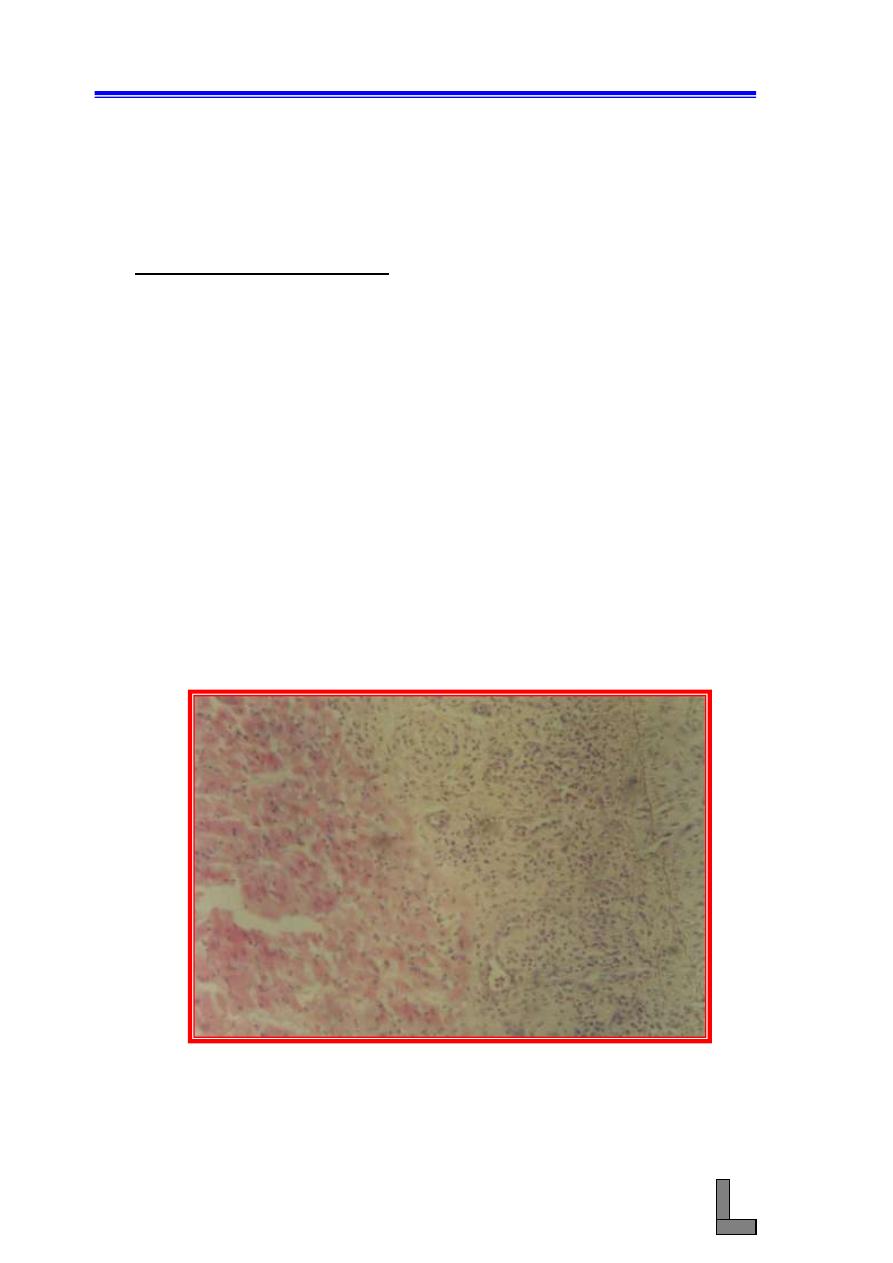

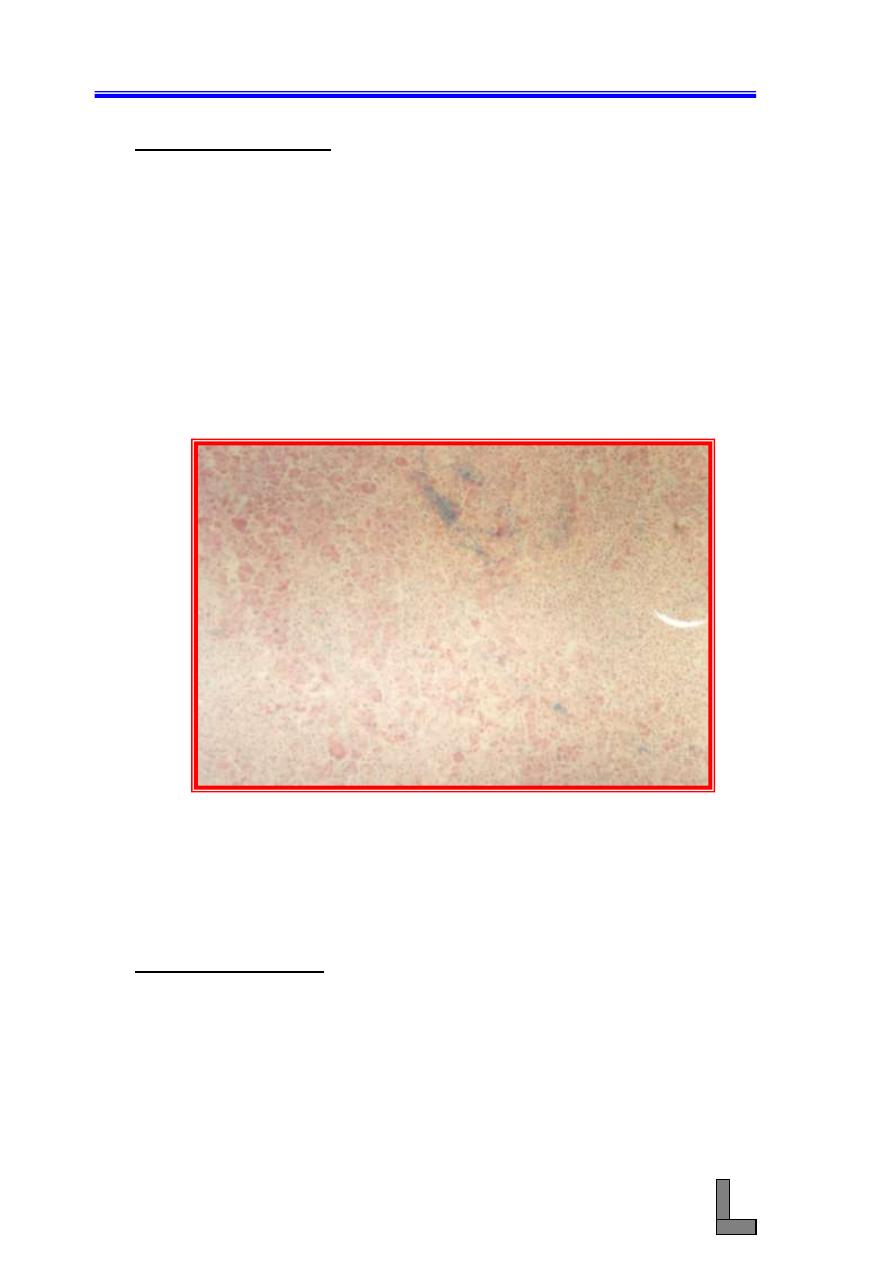

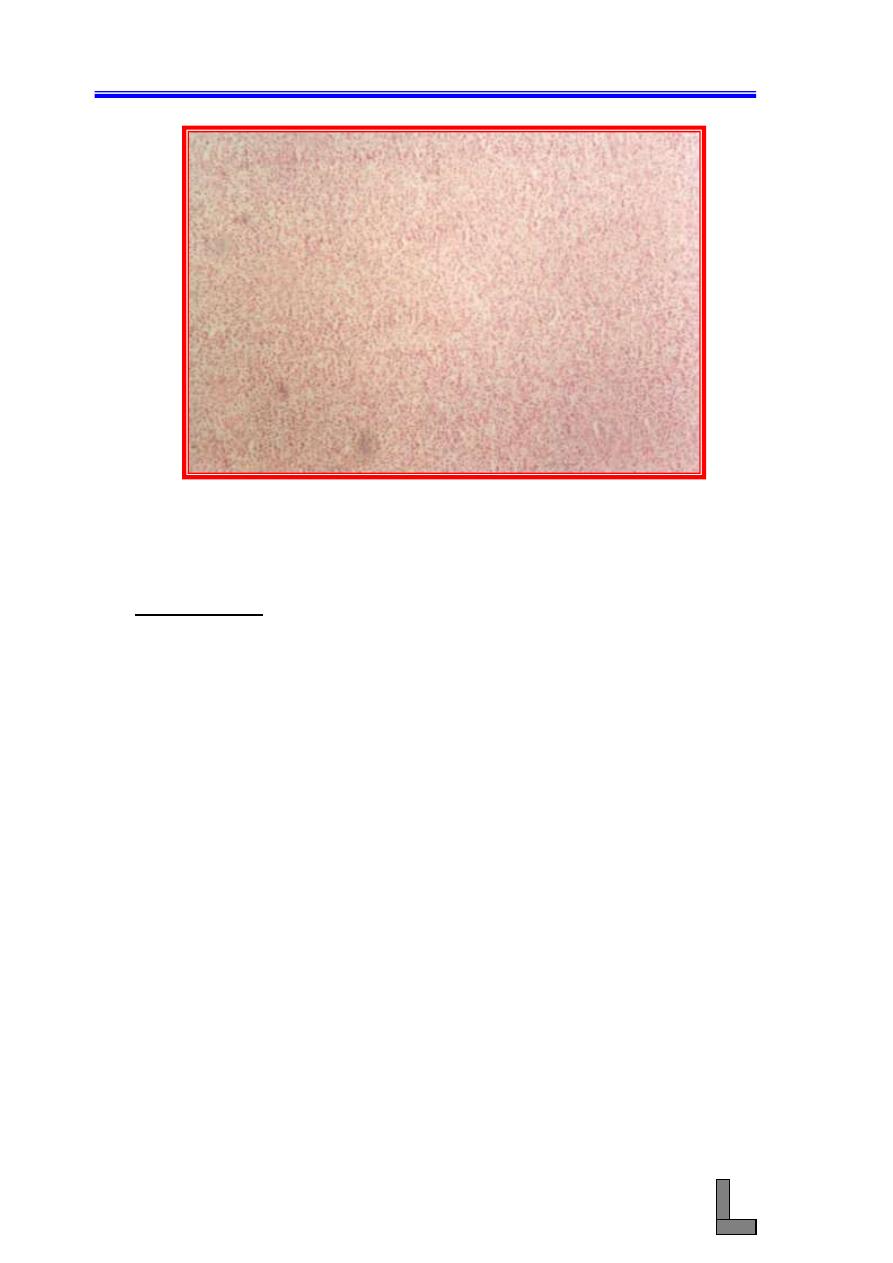

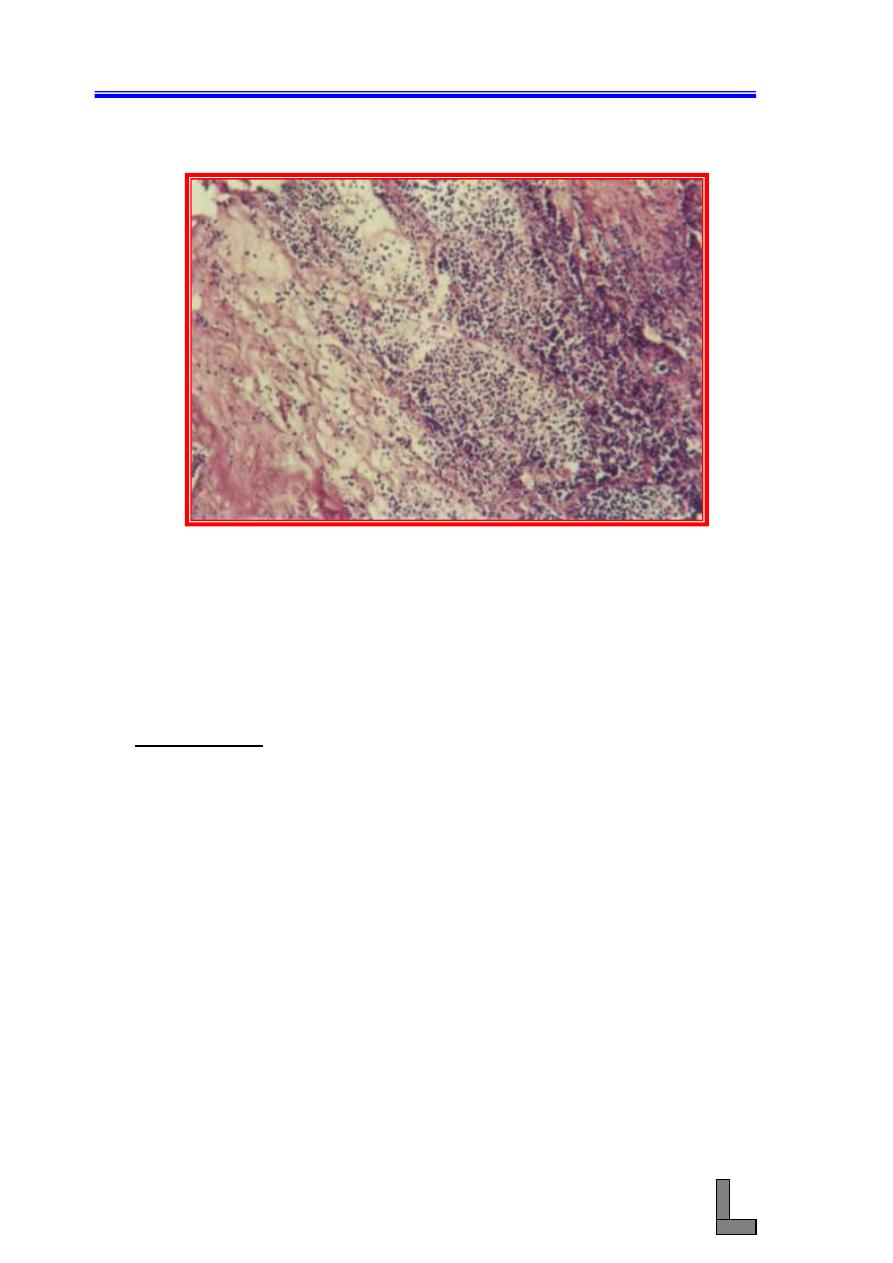

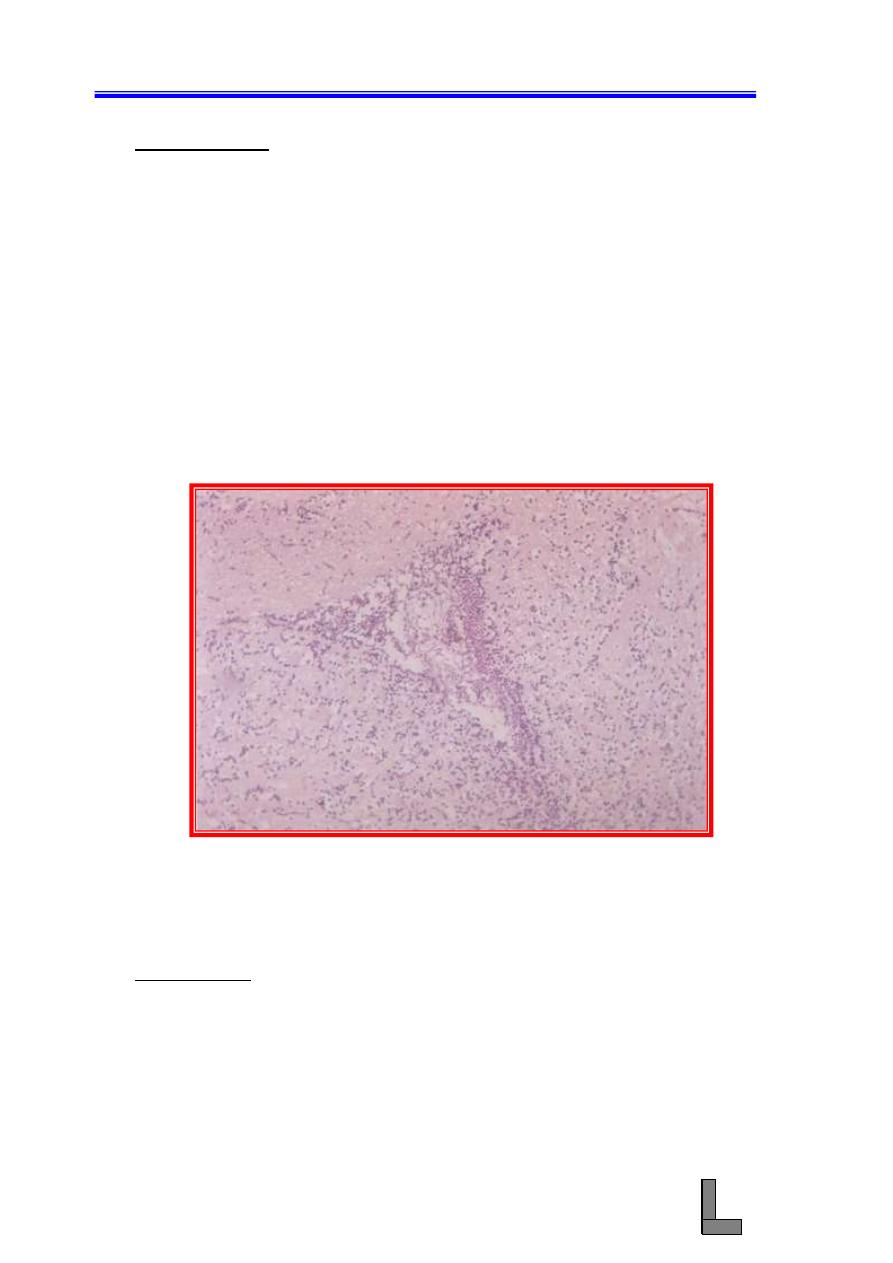

Fig. 42-

Photomicrograph of a lung showing parasitic bronchiolitis.

Developmental stages of lungworms, mucus, and debris

could be seen in the bronchiole (arrow). Thickening of the

bronchiolar wall due to fibrosis and the accumulation of

inflammatory cells could be seen. H&E stain. X 100.

Systemic Pathology (10) : The Respiratory System

56

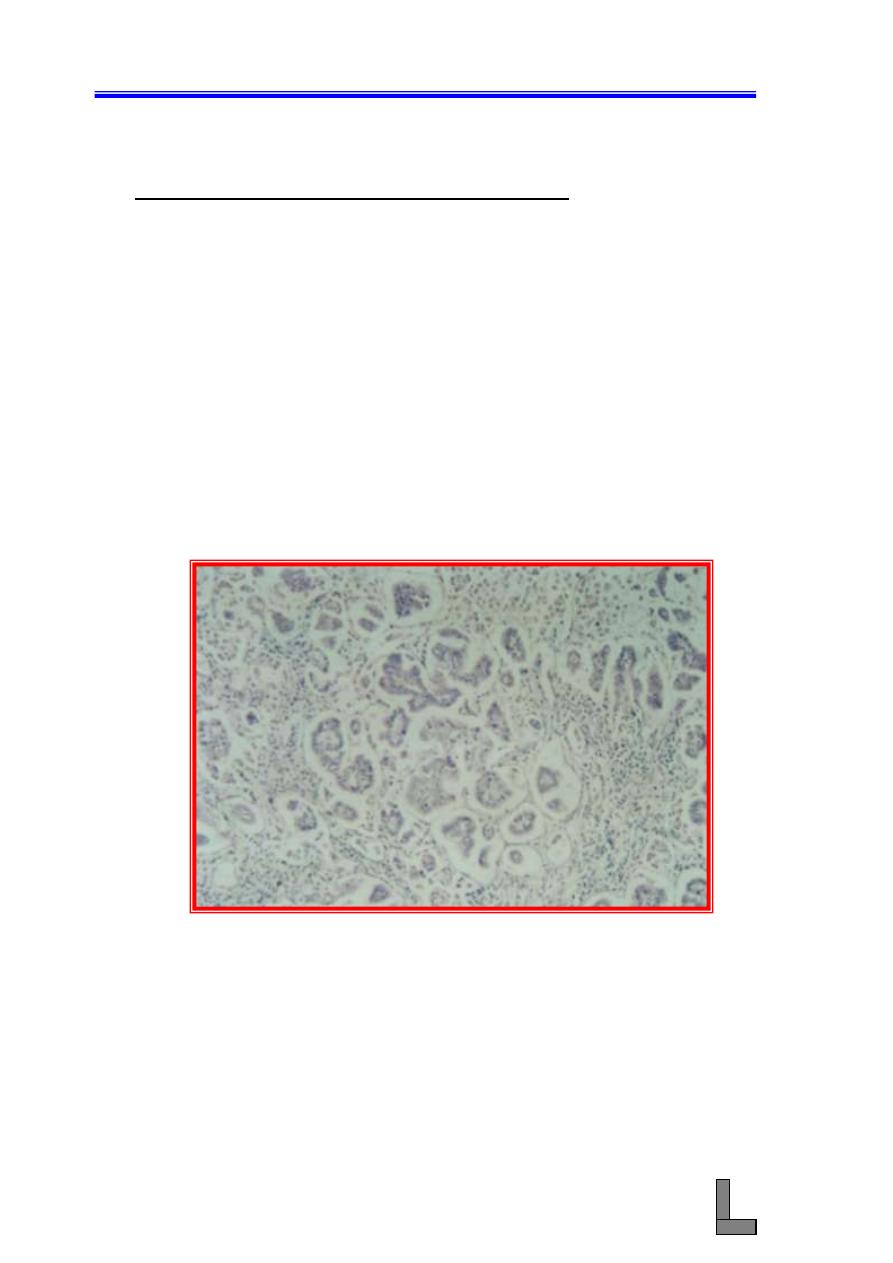

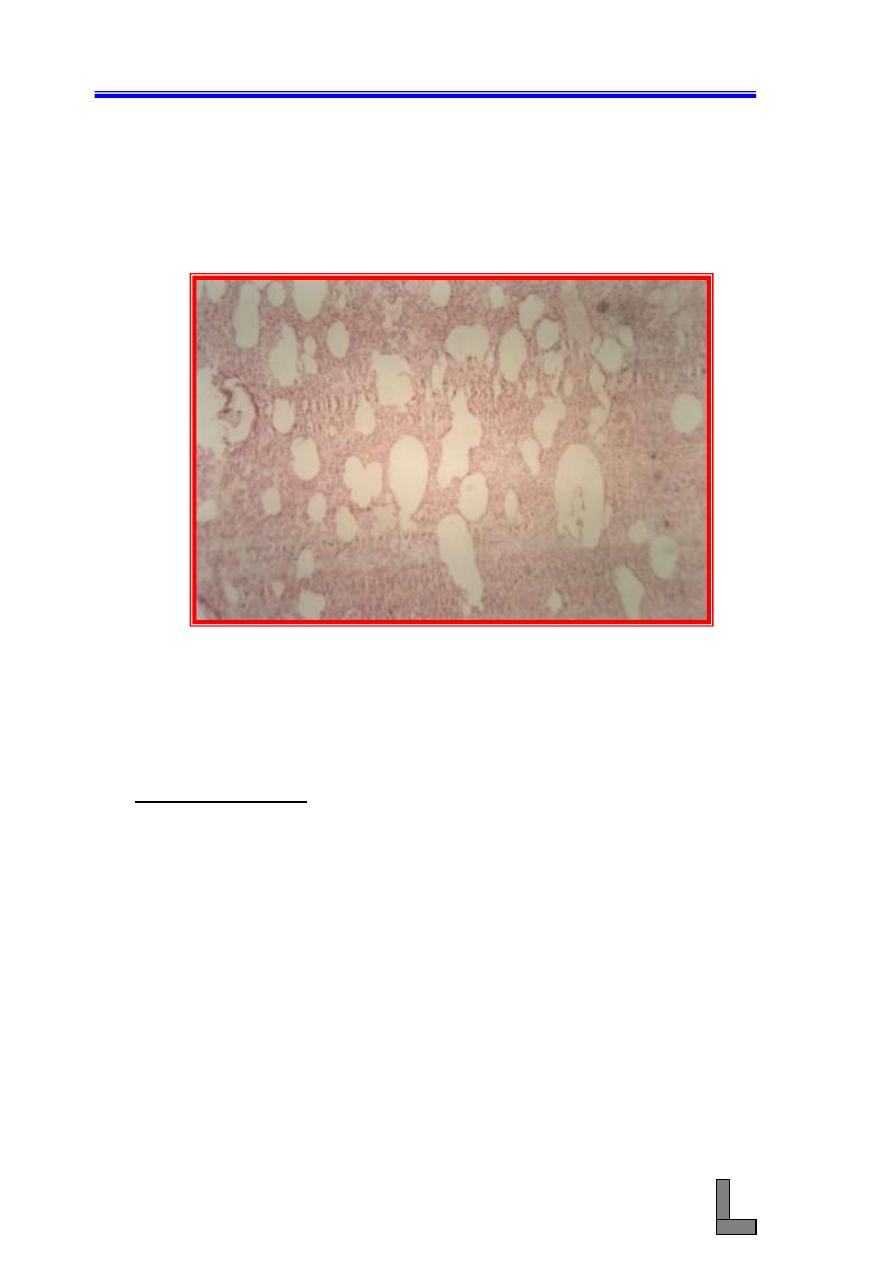

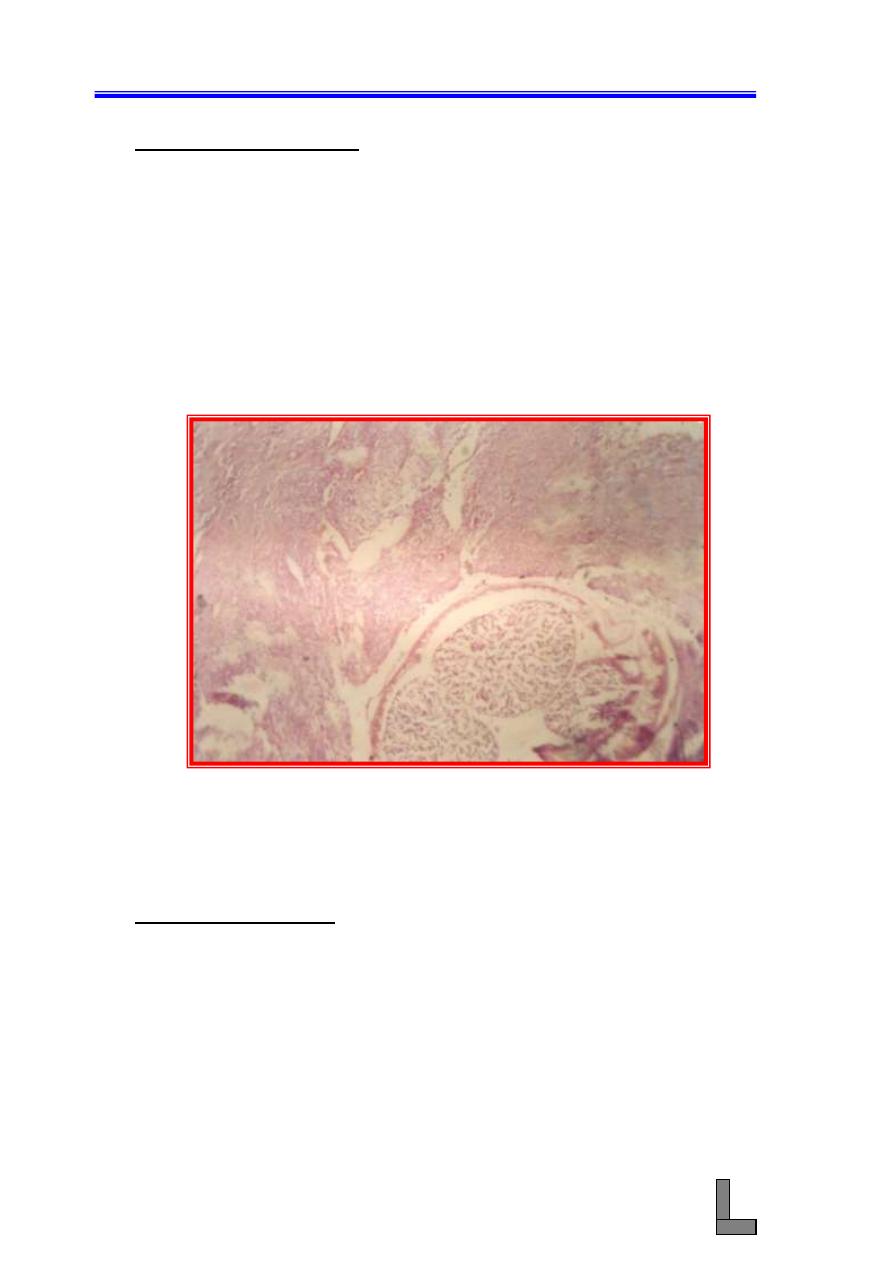

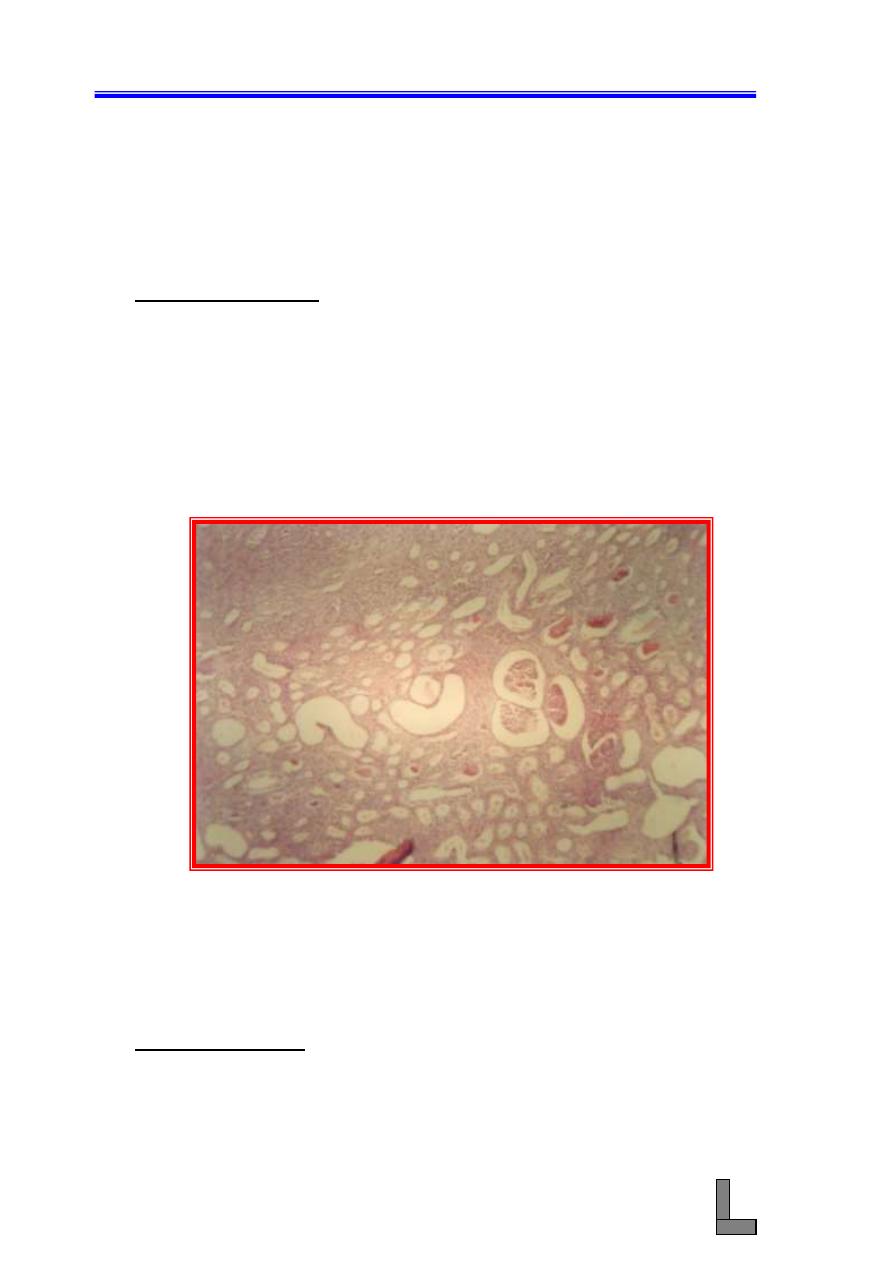

(3) Sheep Pulmonary Adenomatosis (SPA): Also called ovine

pulmonary adenoma, pulmonary carcinoma of sheep, and jaagsiekte.

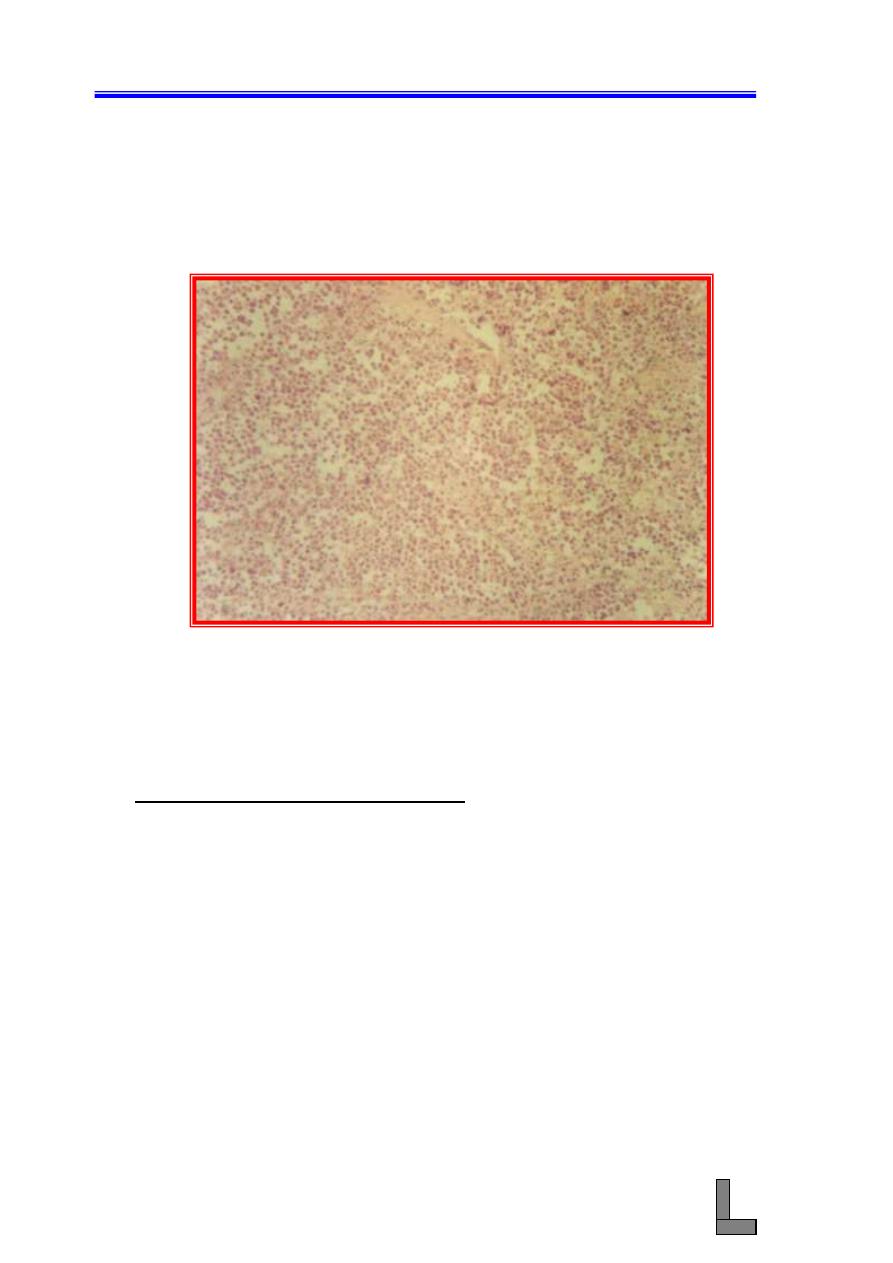

(A) Note multiple foci of neoplastic alveolar type II cells in acinar

and papillary patterns. The result is a pronounced thickening of

the alveolar walls and their interstices and partial obliteration of

the alveolar spaces by small adenocarcinomas.

(B) Lymphocytes accompany the reticuloendothelial cells, and

fibroblasts appear in the later stage (fibrosis).

(C) Mononuclear cells spill over into the alveoli, and accompanied

by a few neutrophils, appear as an exudate in some of the

bronchi.

(D) The peribronchiolar lymph nodes are hyperplastic (markedly

enlarged).

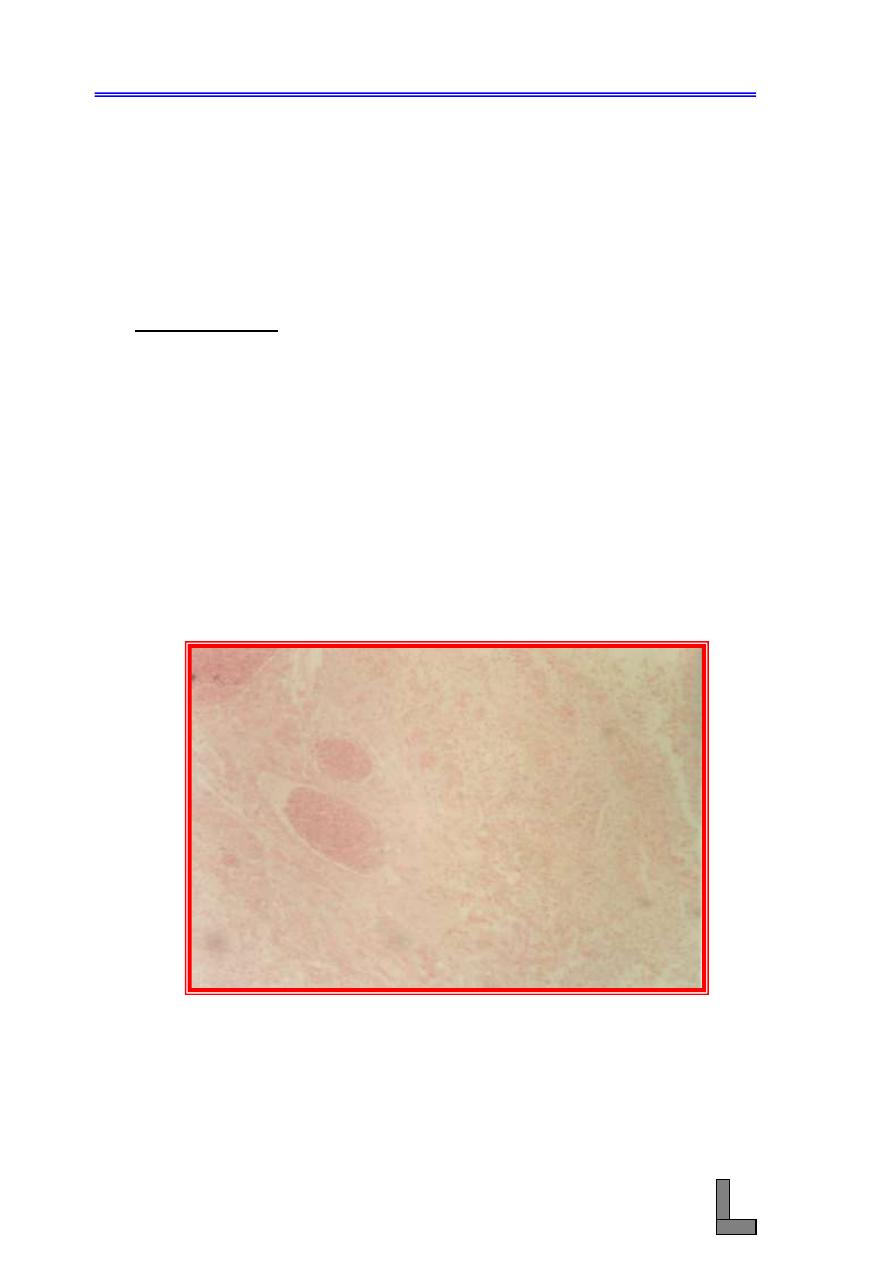

Fig. 43- Photomicrograph of a lung affected with sheep pulmonary

adenomatosis. Note the acinar and papillary patterns of

proliferation of the neoplastic alveolar type II cells. H&E

stain. X 100.

Systemic Pathology (10) : The Respiratory System

57

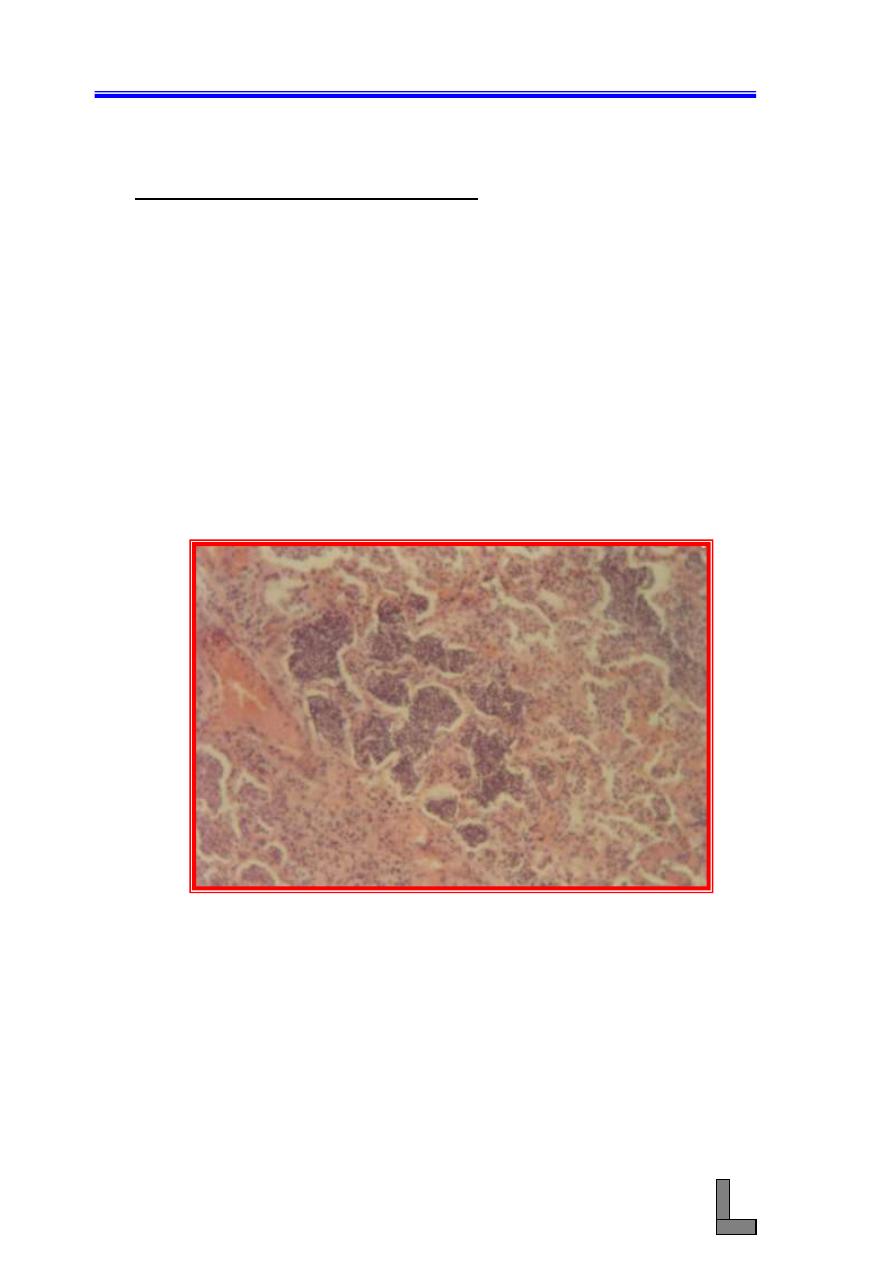

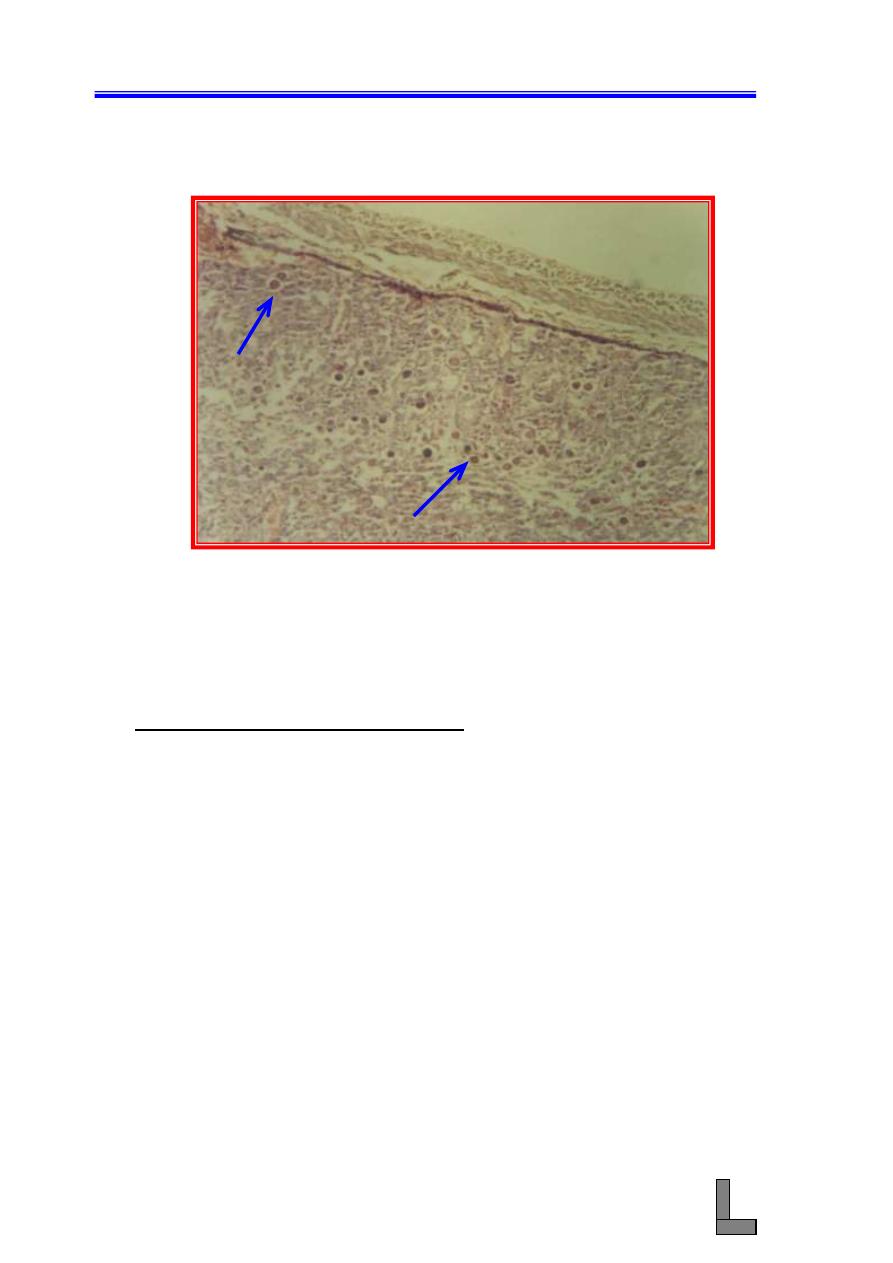

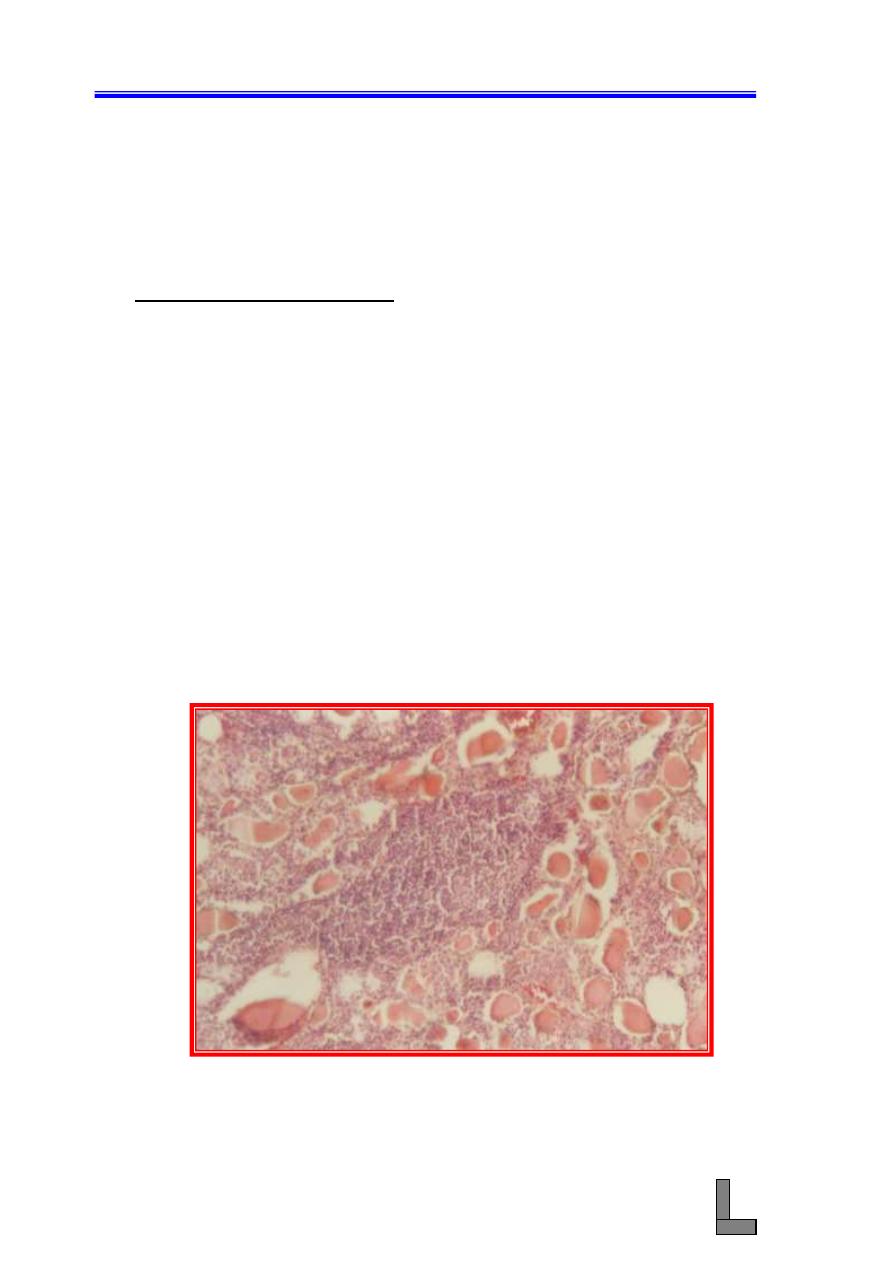

(4) Suppurative bronchopneumonia: When the infectious particles

enters through the bronchial passages the pneumonia is called

bronchial pneumonia or bronchopneumonia. In some cases alveolitis

results from extension of the inflammatory exudates from the

bronchi (called bronchitis) and bronchioles (called bronchiolitis).

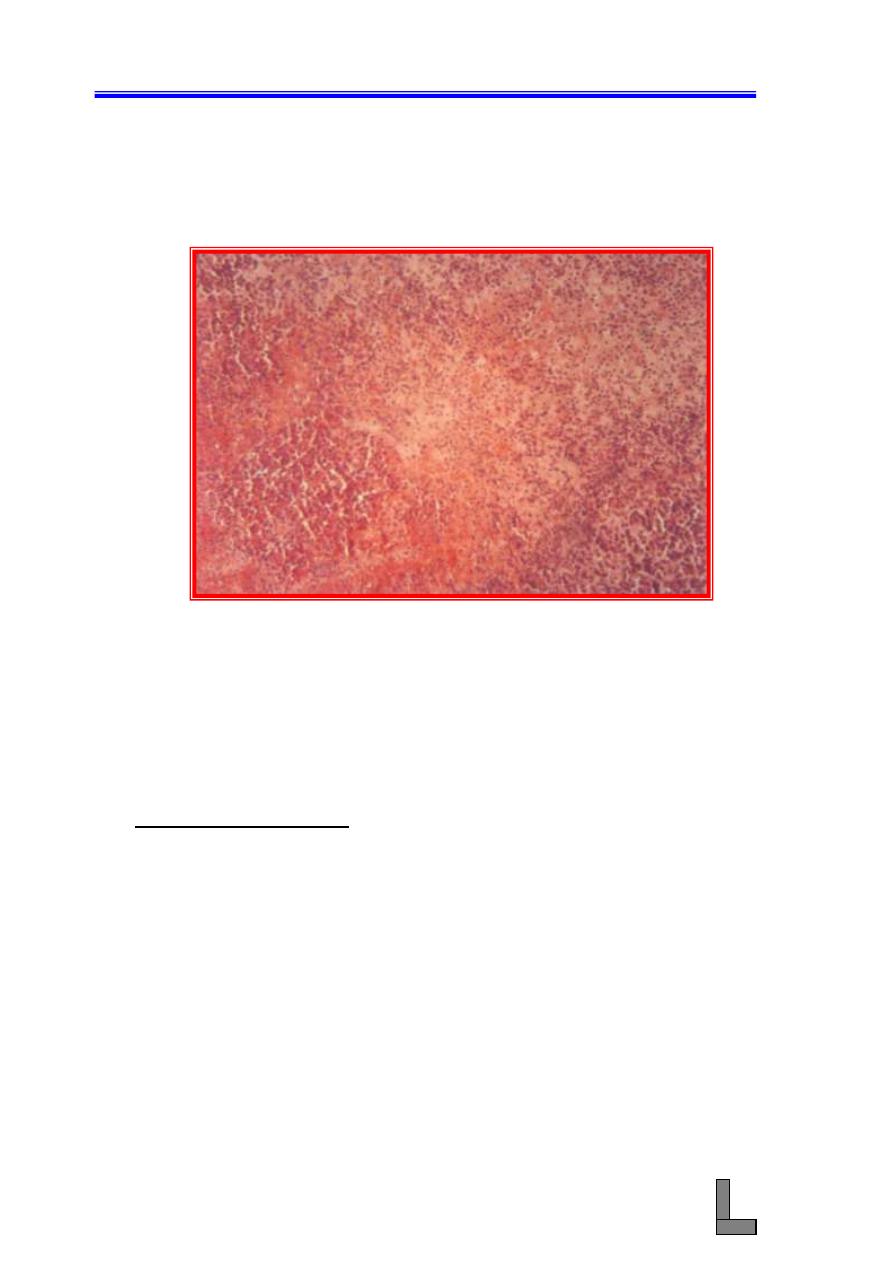

(A) Note extensive infiltration of inflammatory cells (mainly

neutrophils) in the walls and lumens of the bronchi and

bronchioles.

(B) The alveoli are filled with neutrophilic exudate.

(C) Other changes indicative of acute inflammation such as

hyperemia of blood vessels in the walls of bronchioles and

alveoli could also be seen.

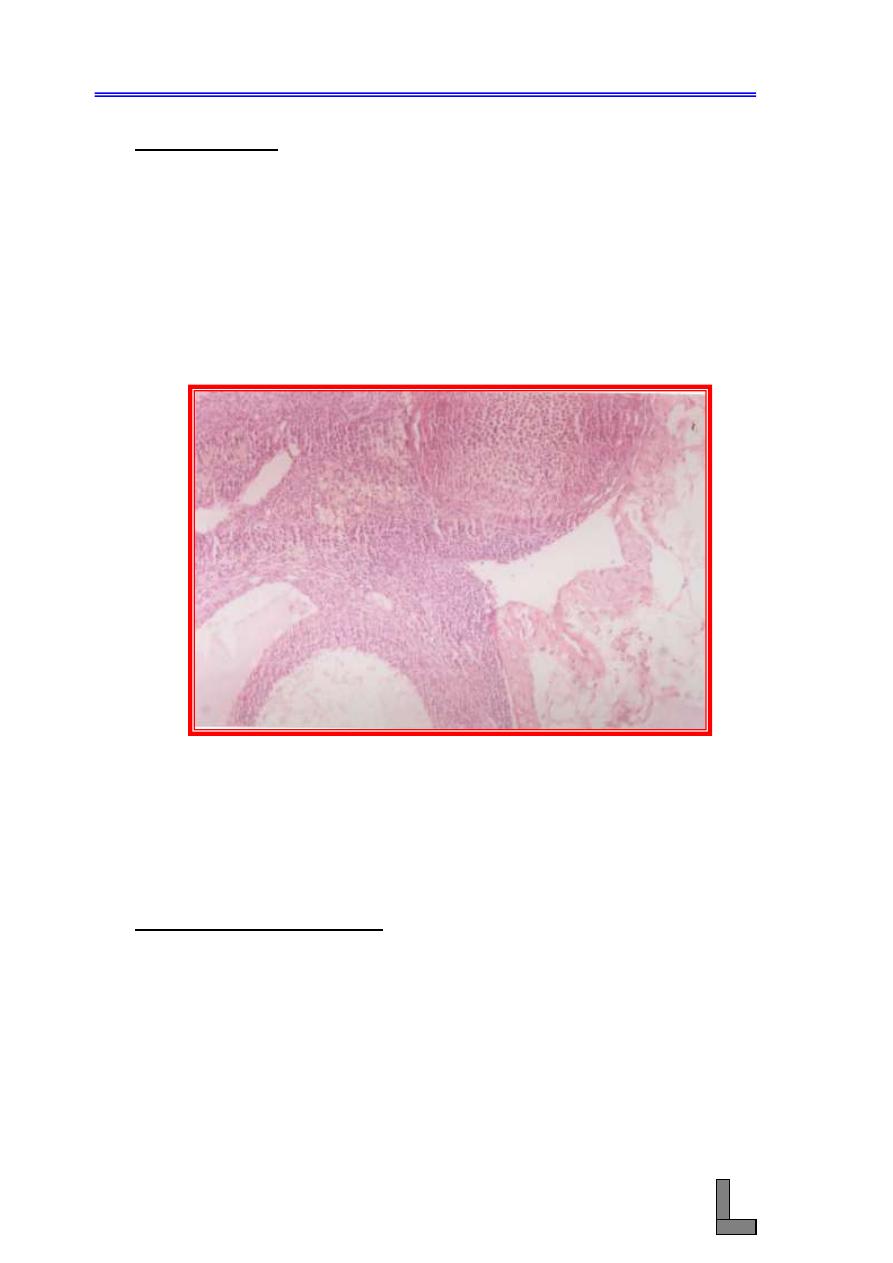

Fig. 44- Photomicrograph of a lung affected with suppurative

bronchopneumonia. Note that the alveoli (and the

bronchioles) are filled with neutrophilic exudate. H&E stain.

X 100.

Systemic Pathology (10) : The Respiratory System

58

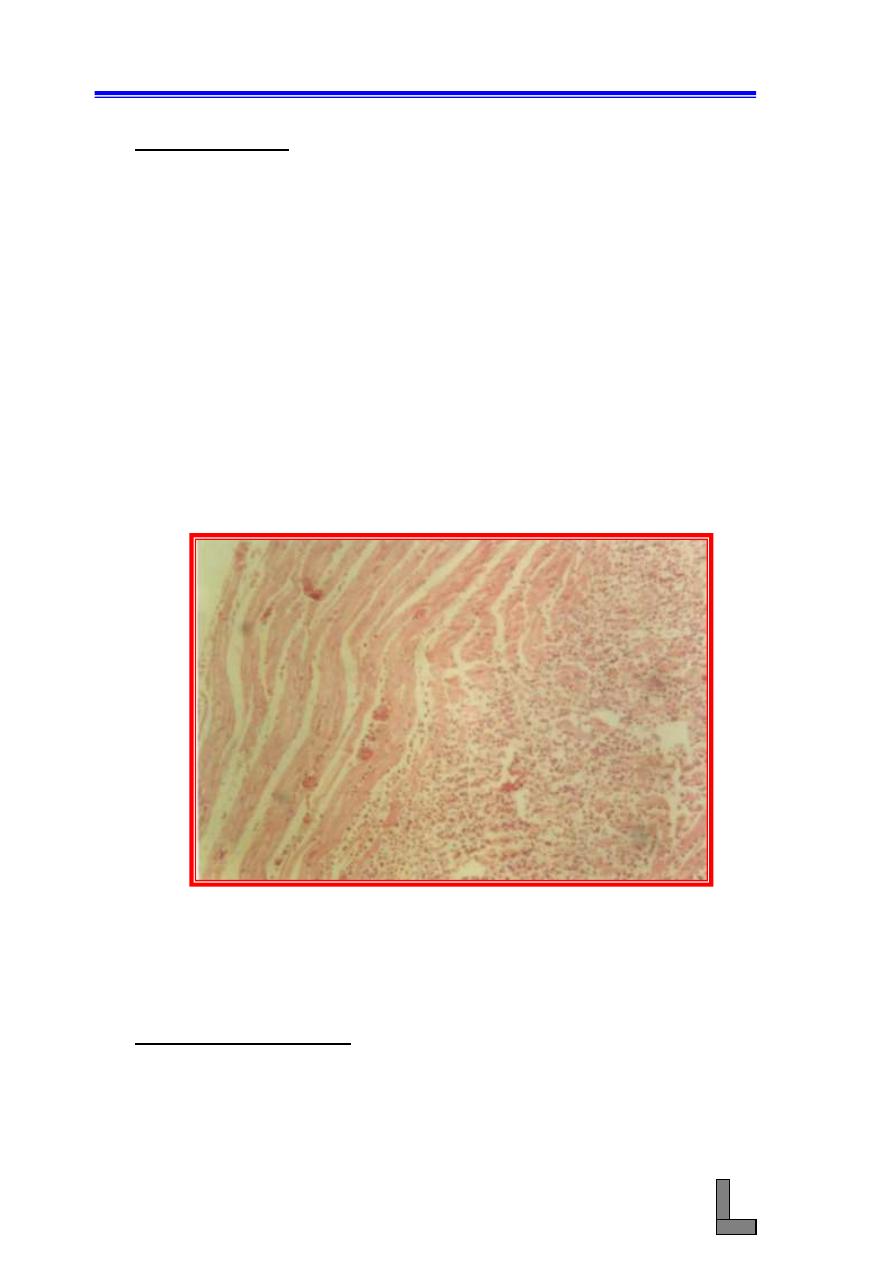

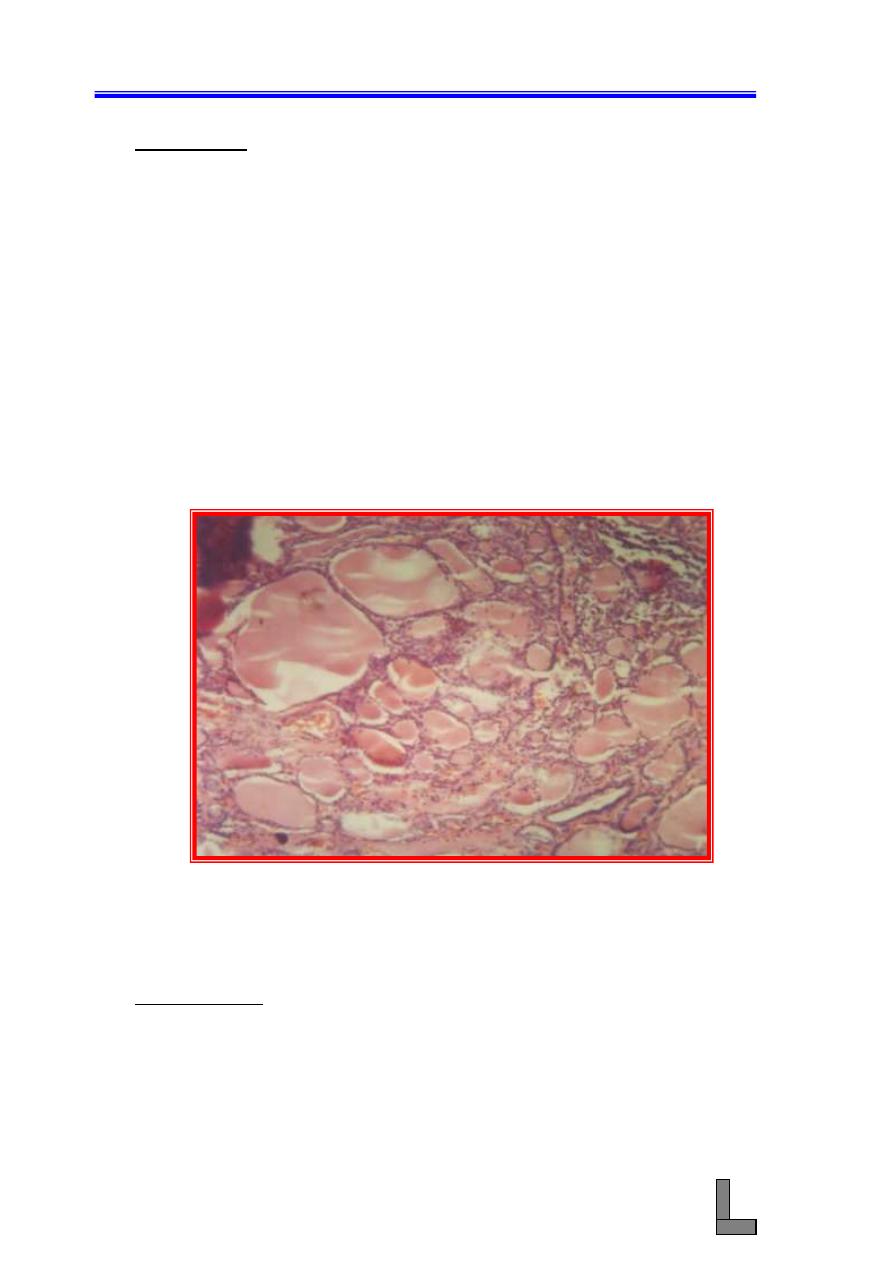

(5) Atelectasis: This term means failure of the alveoli to open or to

remain open; in other words, the empty alveoli are collapsed and do

not contain air. Atelectic portion is dull red in color and has the

consistency of hepatic tissue. Since the atelectic alveoli do not

contain air, the atelectic portion sinks in water.

(A) The alveoli are compressed into scarcely recognizable slits, all

laying parallel in a direction determined by adjacent pressures.

(B) Note that the cells are those of normal lung tissue.

(C) Well – filled capillaries could be seen, but the total blood

content of the atelectic tissue is less than normal.

(D) The bronchioles are collapsed as far as their structure permits.

Fig. 45- Photomicrograph of a lung showing atelectasis. Note collapse of

the alveoli and terminal bronchioles. H&E stain. X 100.

(6) Emphysema: Means the presence of air in the tissues and there are

two kinds, alveolar and interstitial. Alveolar emphysema is more

common and is called pulmonary emphysema.

(A) Many alveoli are too large and many have wide openings into

each other or into a common space due to rupture of alveolar

walls.

(B) The blunt ends of alveolar walls which have been broken often

persist and become thickened and hyperplastic rounded knobs.

Systemic Pathology (10) : The Respiratory System

59

(C) Some of the walls are slightly thickened while others are

stretched and very thin.

(D) Blood – filled capillaries are scarce and the smooth muscle of

the alveolar ducts is often hyperplastic.

Fig. 46- Photomicrograph of a lung affected with emphysema. Many of

the alveoli are too large and open into each other. H&E stain.

X 40.

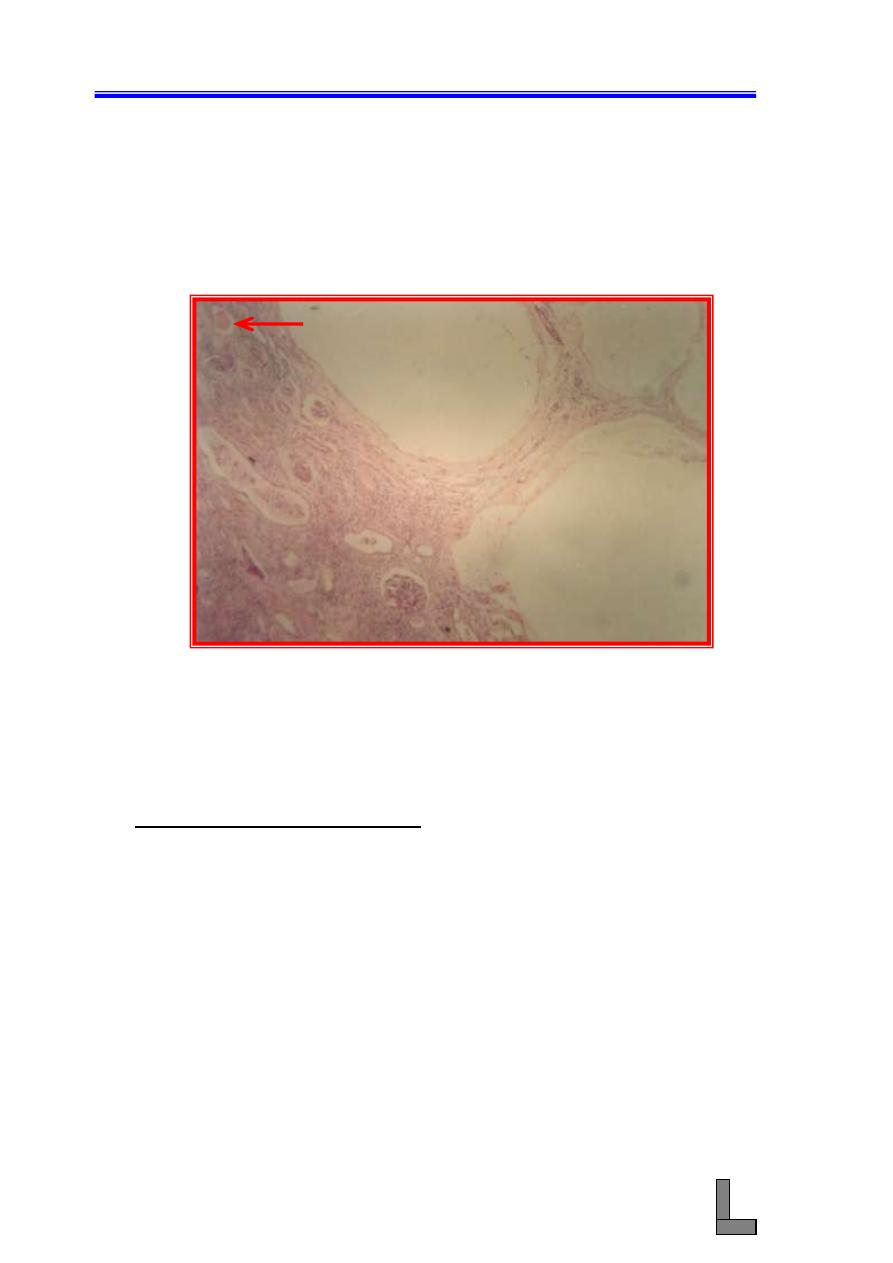

(7) Bronchiectasis: Is one of the most devastating sequel that follows

chronic bronchitis. It consists of pathologic and permanent dilation

of a bronchus as a result of the accumulation of exudates in the

lumen and partial rupture of bronchial walls. Destruction of walls

occurs, in part, when proteolytic enzymes relapsed from phagocytic

cells during chronic inflammation degrade and weaken the smooth

muscle and cartilage that help to maintain normal bronchial

diameter.

(A) The presence of purulent exudate in the dilated bronchus.

(B) Remnants of the bronchial wall surround the exudate.

(C) Differentiate this lesion from pulmonary abscess.

Systemic Pathology (10) : The Respiratory System

60

Fig. 47- Photomicrograph of a lung affected with bronchiectasis. Note the

very large lumen (

L

) and the infiltration of inflammatory

cells in the wall of the bronchiole. Hyperplasia of smooth

muscle could also be noted (

arrows

). H&E stain. X 40.

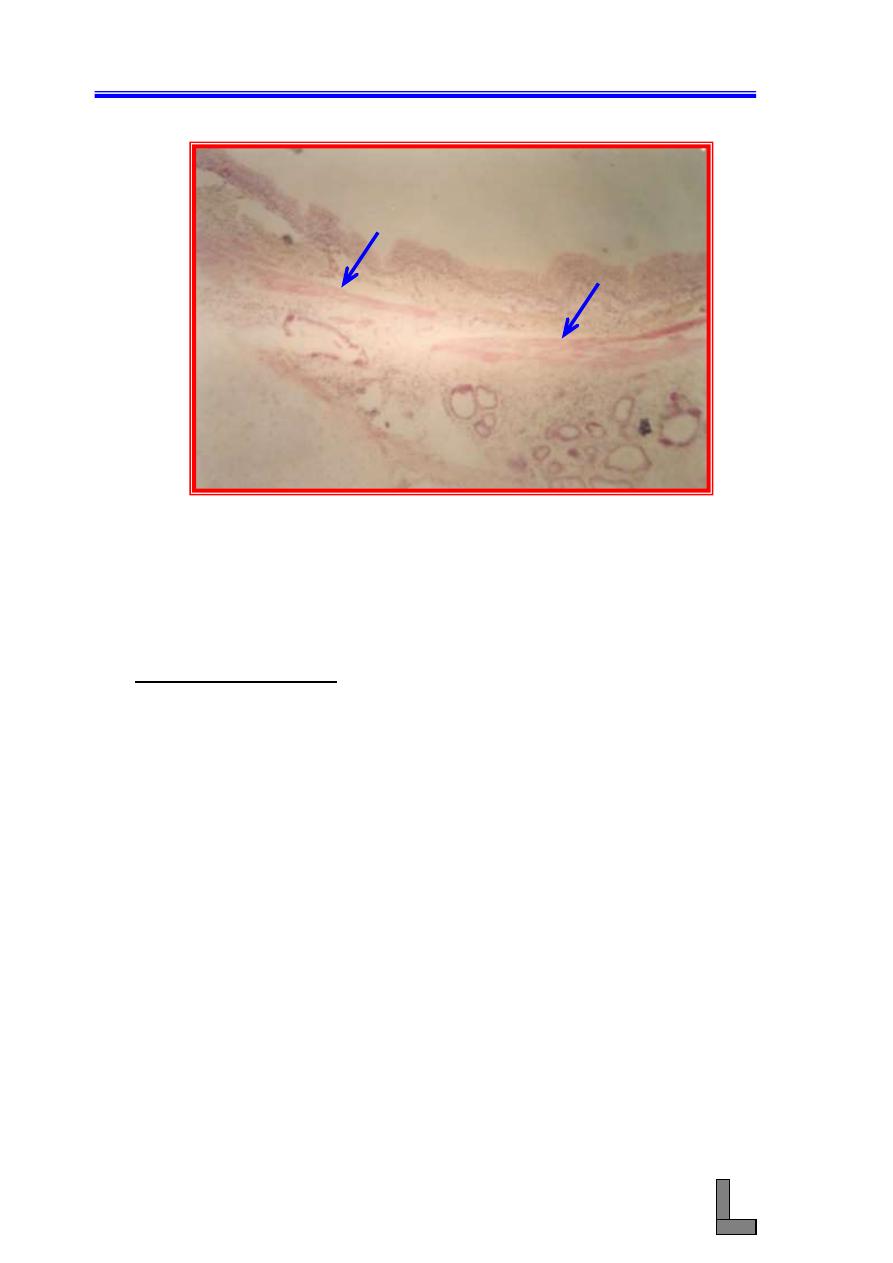

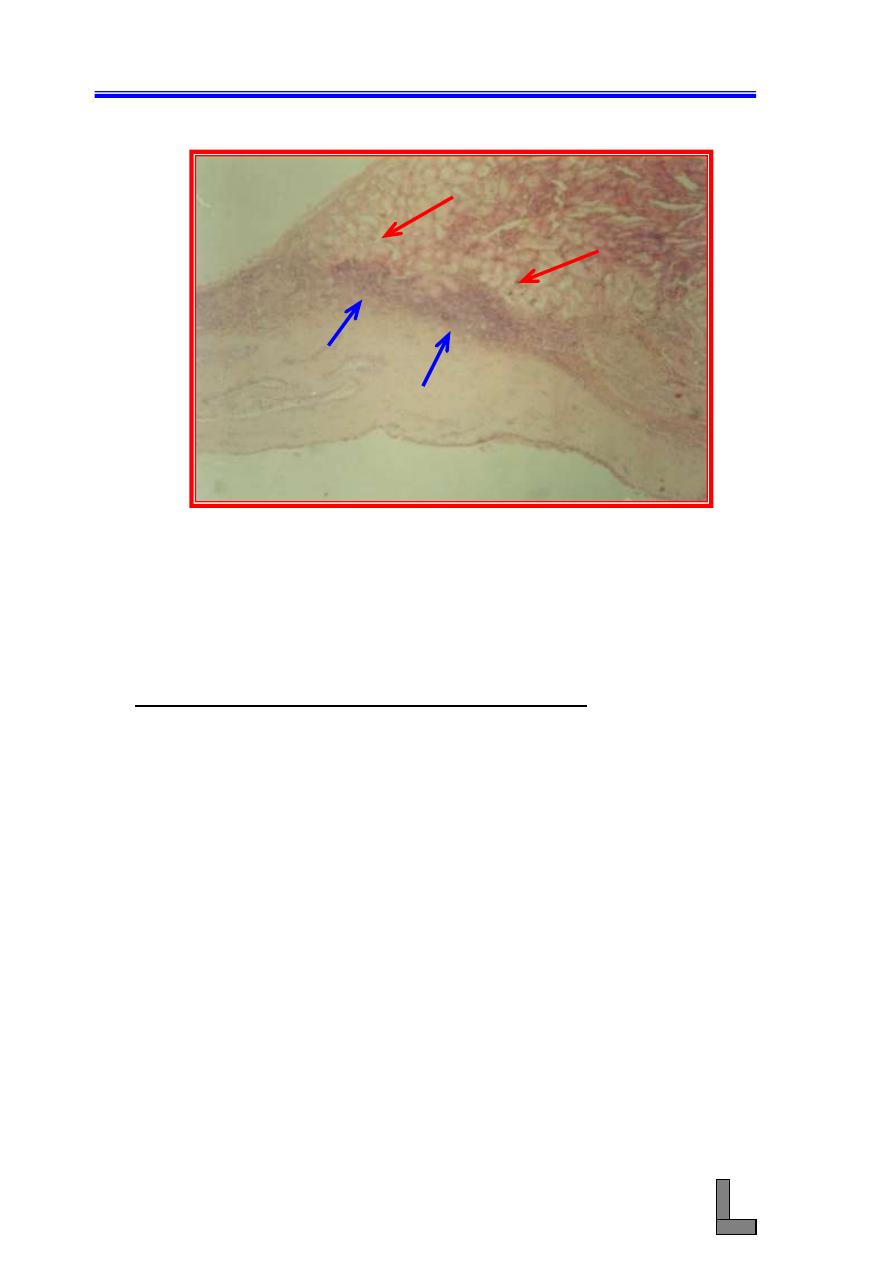

(8) Pleuropneumonia: Pleuritis (pleurisy) means inflammation of the

visceral or parietal pleura. It can occur as part of pneumonia,

particularly in fibrinous bronchopneumonia, and here the condition

is called pleuropneumonia. Bovine and ovine pneumonic

pasteurellosis and bovine pleuropneumonia are good examples of

pleuritis associated with fibrinous bronchopneumonia.

(A) Note the presence of a serofibrinous exudate in the pleura

leading to increased thickness of the pleura.

(B) Widely distributed hyperemia of blood vessels and bacterial

colonies could be seen.

(C) The alveoli are filled with a serofibrinous exudate containing

polymorphonuclear cells and large numbers of erythrocytes.

(D) Inflammatory exudate could also be seen in the bronchi and

bronchioles.

L

Systemic Pathology (10) : The Respiratory System

61

Fig. 48- Photomicrograph of a lung affected with pleuropneumonia. Note

the accumulation of serofibrinous exudate in the pleura (1)

and hyperemia and inflammation of the lung tissue (2). H&E

stain. X 100.

(9) Interstitial Pneumonia: In this type of pneumonia, the inflammatory

process takes place primarily in any of the three layers of the

alveolar walls (endothelium, basement membrane, and alveolar

epithelium) and the contiguous bronchiolar interstitium.

(A) Note the thickened bronchiolar walls due to accumulation of

inflammatory cell infiltrate in the mucosa and its extension

peribronchially into the alveolar interstitium. This change is

called bronchiointerstitial pneumonia.

(B) Although the lesions in interstitial pneumonia are centered in the

alveolar walls and interstitium, a mixture of desquamated

epithelial cells, macrophages, and mononuclear cells are usually

present in the lumen of bronchioles and alveoli.

(C) Hyperplasia of smooth muscle in airways or pulmonary

vasculature, and microscopic granulomas could be seen.

1

2

Systemic Pathology (10) : The Respiratory System

62

Fig. 49- Photomicrograph of a lung affected with interstitial pneumonia.

Note the increased thickness of the alveolar interstitium due

to infiltration of mononuclear cells. X 100.

(10) Mycotic Pneumonia: The most common causes of granulomatous

pneumonia in animals include systemic fungal diseases such as

Cryptococcosis (Cryptococcus neoformans), Coccidioidomycosis

(Coccidioides immitis), Histoplasmosis (Histoplasma capsulatum),

and blastomycosis (Blastomyces dermatitidis).

Fig. 50- Photomicrograph of an avian lung showing mycotic pneumonia.

Note severe inflammation of the pulmonary tissue. A

thrombosed blood vessel could be seen. H&E stain. X 100.

Systemic Pathology (10) : The Respiratory System

63

References:

Brogden KA, Lehmkul HD, Cutlip RC. Pasteurella haemolytica complicated

respiratory infections in sheep and goats. Vet Res 1998; 29 :

233-254.

Carrman S, Rosendal S, Huber L, Gyles C, Mckee S, Willoughby RA, Dubovi

E, Thorsen J, Lein D. Infectious agents in acute respiratory

disease in horses in Ontario. J Vet Diag Invest 1997; 9:17-23.

De La Concha

– Bermejillo A. Maedi – Visna and ovine progressive

pneumonia. Vet clin North Am Food Anim Pract 1997; 13:13-33.

Dungworth DL. The respiratory system. In : Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer

N, eds. Pathology of domestic animals. 4th ed. New York :

Academic Press, 1993: 539.

Hondalus MK. Pathogenesis and virulence of Rhodococcus equi. Vet

Microbiol 1997; 56:257-268.

Lopez A. Respiratory system, thoracic cavity, and pleura. In: McGavin MD,

Carlton WW, Zachary JF. Eds. 3rd ed. Thomson's special

veterinary pathology. St. Louis : Mosby, 2001 : 125 - 195.

Moulton JE. Tumors of the respiratory system. In: Moulton JE, ed. Tumors in

domestic animals. 3rd ed. Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1990:308.

Systemic Pathology (11) : The Digestive System

64

Systemic Pathology (11)

The Digestive System

(1) Parasitic Glossitis: Among parasites that are seen in the tongue of

ruminants are the tapeworms (Cysticercus bovis, Cysticercus ovis),

protozoa (Sarcocystic spp), and round worms (Gongylonema spp).

Cysticercus bovis, the larva of Taenia saginata occurs in muscle,

liver, heart, lungs, diaphragm, lymph nodes, and other parts. On the

other hand, Cysticercus ovis, the larva of Taenia ovis occurs in the

heart, voluntary muscles, diaphragm, esophagus, and rarely the lung.

(A) Note the presence of multiple larvae beneath the lingual mucosa

and in between the bundles of muscle fibers of the tongue.

(B) Minimal tissue response occurred against the presence of the

larva. This response is in the form of thin inflammatory layer

with connective tissue response.

(C) Note atrophy of some of the bundles of muscle fibers close to

the larva (pressure atrophy).

(D) Sarcocystic spp could also be seen in the muscle fibers.

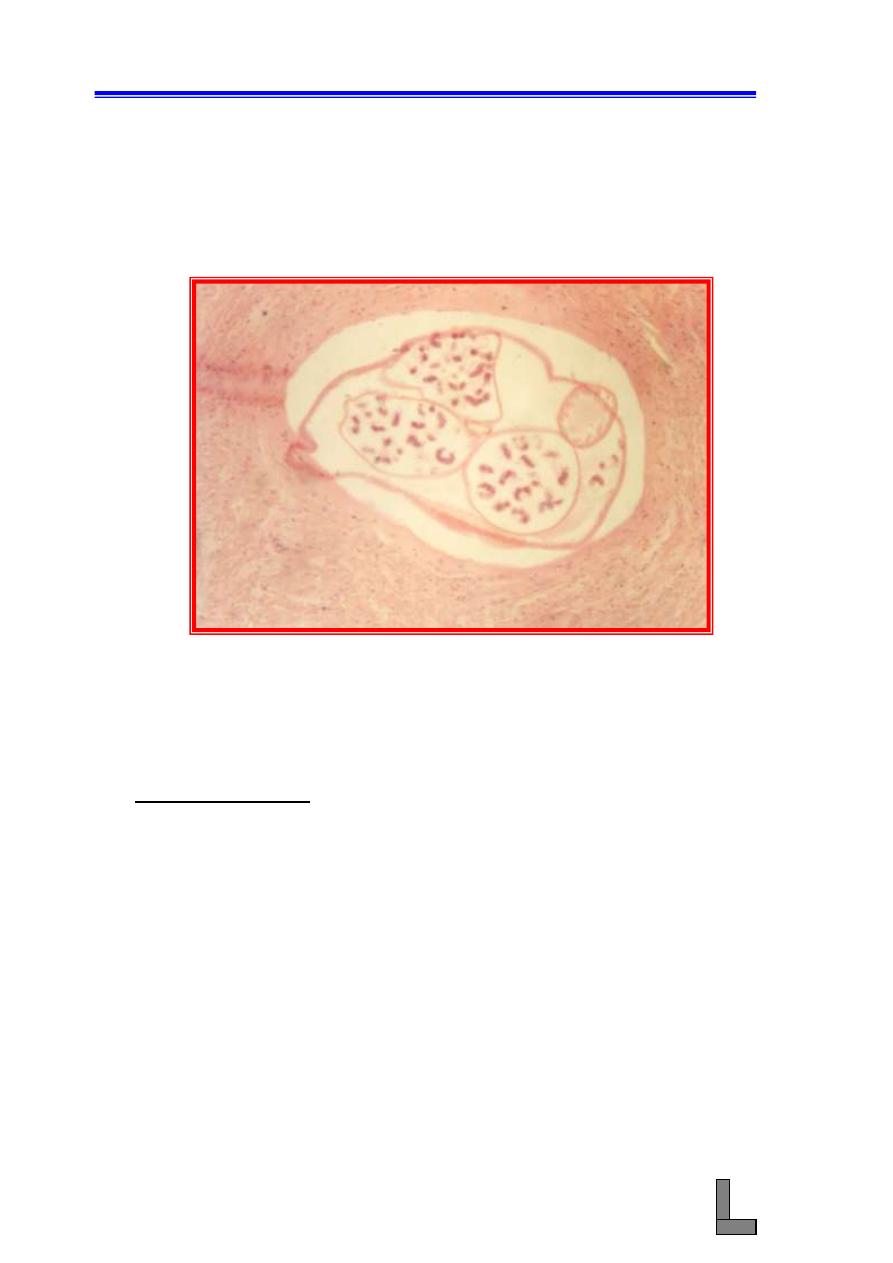

Fig. 51- Photomicrograph of a tongue affected with both cysticercosis

and sarcocystosis (parasitic glossitis). Note the presence of

the cysticercus larva (

S

) in the lingual tissue (

L

). H&E stain.

X 40.

S

L

Systemic Pathology (11) : The Digestive System

65

(2) Parasitic esophagitis: Infection with the spiruroid worm, Spirocerca

lupi (also called the esophageal worm) is particularly common in

dogs in many parts of the world. The adult worms are usually found

in nodules in the wall of the esophagus, aorta, stomach, and other

organs of the dog, fox, wolf, and cat. Grossly, one or more nodules

are seen in the luminal surface, elevating the epithelium with the

presence of the worms in these nodules. Microscopically:

(A) Sections of adult Spirocerca lupi worms could be seen in the

wall of the esophagus.

(B) The worms are surrounded by thick metaplastic connective

tissue.

Fig. 52- Photomicrograph of the wall of the esophagus of a dog infected

with Spirocerca lupi . A cross section of an adult worm (

W

)

could be seen in a fibrous tissue nodule (

F

). H&E stain.

X 40.

(3) Parasitic Enteritis: Coccidia are host – and tissue – specific protozoa

and obligate intracellular pathogens. They cause lesions that could

be proliferative or hemorrhagic. In epithelial cells of the villi or

crypts, the organism undergo one or more asexual reproductive

cycles, with the resulting sporozoites producing schizonts that

contain from few to thousands of merozoites. The latter enter new

cells and repeat the cell cycle. Microscopically:

(A) Section of the intestine showing vascular and cellular changes

indicative of inflammation (enteritis).

F

F

F

W

Systemic Pathology (11) : The Digestive System

66

(B) Numerous stages of the life cycle of Eimeria spp could be seen

in the mucosa and submucosa.

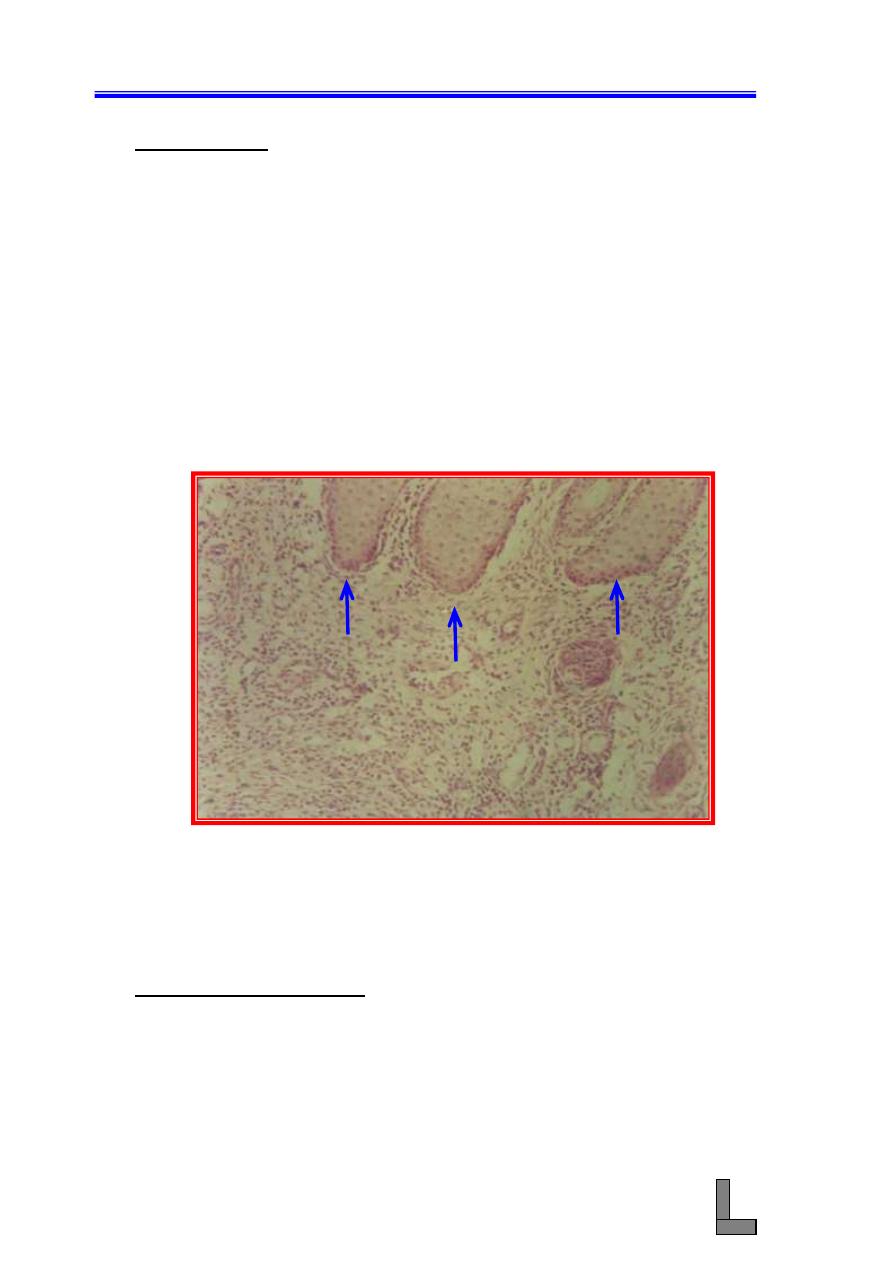

Fig. 53- Photomicrograph of the small intestine of a laboratory animal

affected with intestinal coccidiosis. Note the presence of

various developmental stages of the parasite (Eimeria spp.)

(

arrows

) and the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the

intestinal mucosa. H&E stain. X 100.

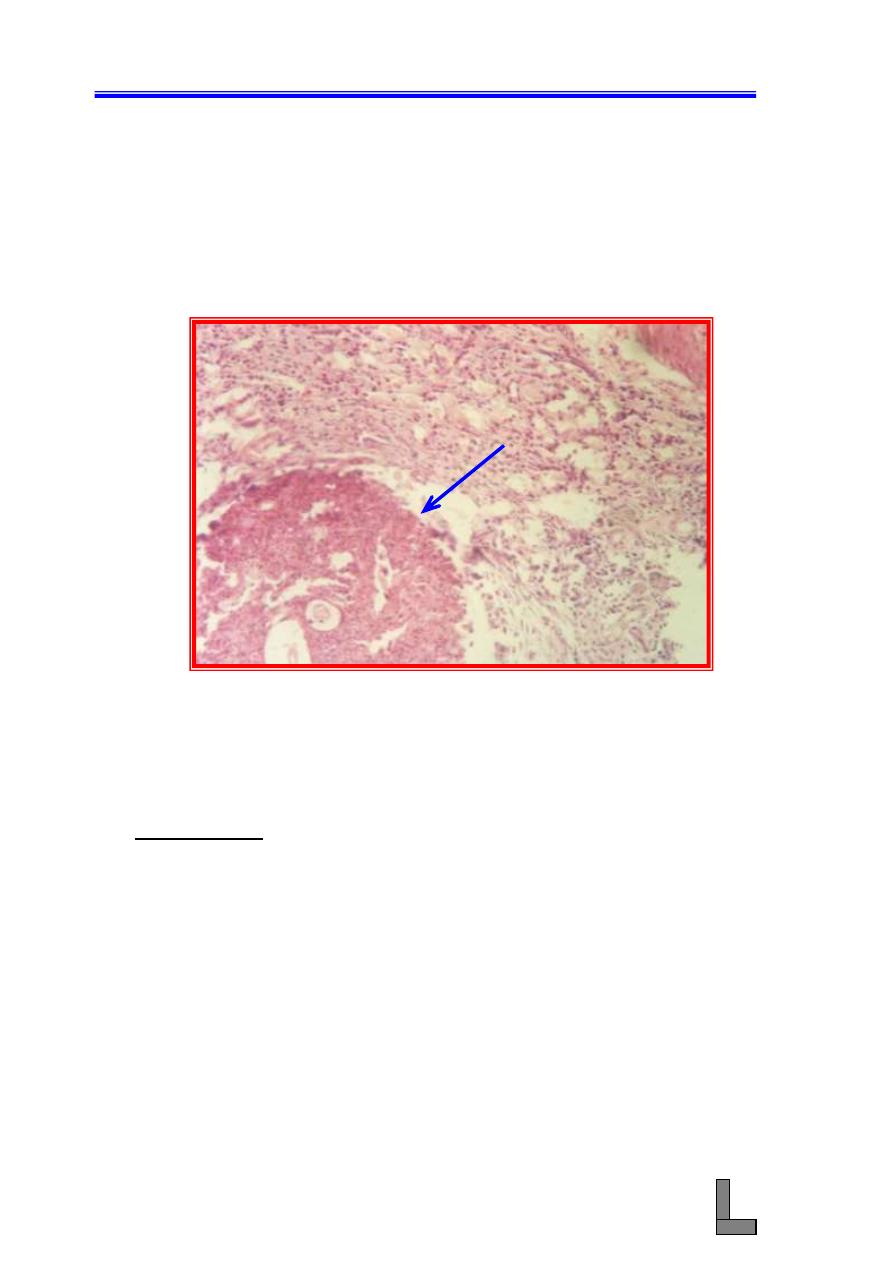

(4) End - Stage liver or Cirrhosis: This is characterized by loss of

normal hepatic architecture due to nodular regeneration of

parenchyma, fibrosis, and often biliary duct hyperplasia. The

condition could be defined as a diffuse process characterized by

fibrosis and conversion of normal liver architecture into structurally

abnormal lobule. It could also be defined as the total absence of any

normal lobular architecture. Among causes of this condition are

toxic plants (hepatotoxins) and anticonvulsant drugs such as

Primidone. Microscopically:

(A) The architecture of the liver is altered by loss of hepatic

parenchyma, condensation of reticulin frame work, and

formation of tracts of fibrous connective tissue.

(B) Regeneration of hepatic tissue between fibrous bands leads to the

formation of variably sized regenerative nodules.

(C) Diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells could be seen in both

the hepatic parenchyma (hepatitis) and the fibrous tissue.

Systemic Pathology (11) : The Digestive System

67

Fig. 54- Photomicrograph of a liver exhibiting cirrhosis. Lack of normal

lobular architecture of the liver (L) and the formation of

fibrous tissue tract (T) could be seen. Heavy infiltration of

inflammatory cells could be seen in both the liver tissue and

the fibrous tract. H&E stain. X 100.

References:

Bowman DD. Georgi's parasitology for veterinarians. 7th ed. Philadelphia:

Saunders, 1999.

Gelberg HB. Alimentary system. In : McGavin MD, Carlton WW, Zachary JF.

Eds. 3rd ed. Thomson's special veterinary pathology. St. Louis :

Mosby, 2001 : 1 - 124.

Kelly WR. The liver and billiary system. In: Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N.

eds. Pathology of domestic animals. 4th ed. New York:

Academic Press, 1985:239.

Moon HW. Intestine. In : Cheville NF, ed. Cell pathology. 2nd ed. Ames, IA:

Iowa state University Press, 1983:503-529.

T

L

Systemic Pathology (12) : Cardiovascular System

68

Systemic Pathology (12)

Cardiovascular System

(1) Fibrinous Pericarditis:- This is the most common type of

pericardial inflammation in animals, is usually the result of

hematogenously spread infection. Specific diseases with this lesion

include pasteurellosis, blackleg, coliform septicemias, and sporadic

bovine encephalomyelitis in cattle; streptococcal infections in horse;

and psittacosis in birds.

Grossly, both the visceral and parietal pericardial surfaces

are covered by variable amounts of yellow fibrin deposits that can

result in adherence between parietal and visceral layers. When the

pericardial sac is opened at necropsy, these attachments are torn

away (so – called bread – and – butter heart). Microscopically:

(A) Note the presence of an eosinophilic layer of fibrin with

admixed neutrophils over the congested pericardium.

(B) Bacterial colonies could also be seen in the pericardium.

(C) Fibrous organization of the exudates could be visualized

and this leads to adhesion between the pericardial surfaces.

(D) Atrophy and edema of myocardial fibers could be seen.

Fig. 55- Photomicrograph of a heart showing fibrinous pericarditits. An

extensive fibrinous exudate (

F

) could be seen closely

attached to the myocardium (

M

). H&E stain. X 40.

M

F

Systemic Pathology (12) : Cardiovascular System

69

(2) Myocarditis:- Most commonly results from hematogenous spread of

infections to the myocardium and occurs in various systemic

diseases. Infrequently, myocarditis is the primary lesion in affected

animals and responsible for their death. Myocarditis could be

suppurative, necrotizing, hemorrhagic, lymphocytic, or eosinophilic.

In the suppurative type, the inflammation results from localization of

pyogenic bacteria in the myocardium. These often originate from the

vegetations of vegetative valvular endocarditis on the mitral and

aortic valves.

(A) Note the presence of foci consisting of bacterial colonies

neutrophils, and necrotic myocytes (abscesses) in the

myocardium.

(B) A tract could be seen in the myocardium indicating that the

inflammation may be traumatic.

(C) Zenker’s necrosis of myocytes could be seen in the viscinity

of the tract.

Fig. 56- Photomicrograph of a heart exhibiting myocarditis. Note the

heavy infliltration of inflammatory cells between the

bundles. The exudate has replaced some of the muscle fibers.

H&E stain. X 100.

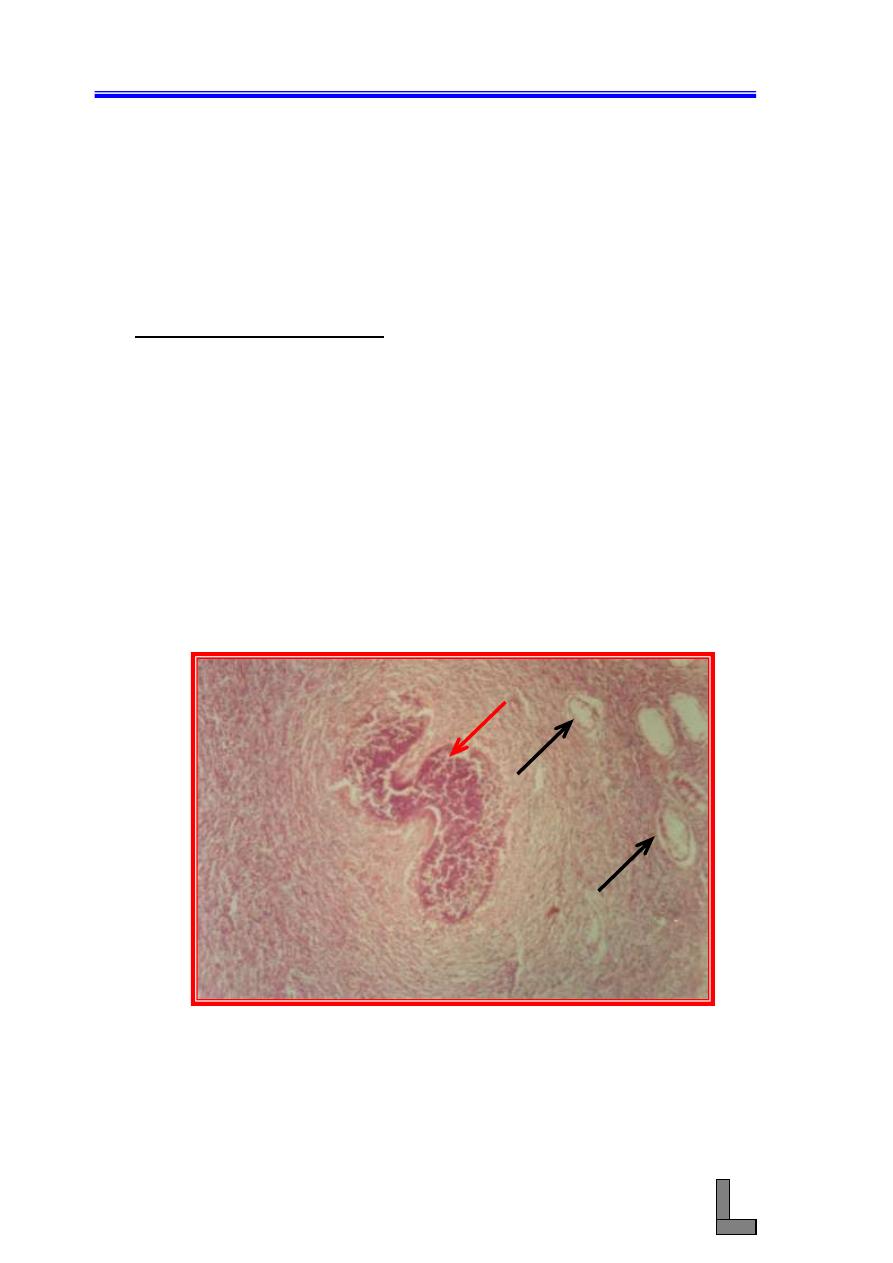

(3) Parasitic arteritis:- Arteritis is a prominent feature of several

parasitic diseases. Examples include dirofilariasis (Dirofilaria

immitis), Spirocercosis (Spirocerca lupi), Onchocerciasis, filariasis,

and angiostrongylosis.

Systemic Pathology (12) : Cardiovascular System

70

(A) Note thickening of wall of the artery (aorta) due to extensive

infiltration of inflammatory cells and proliferation of

fibroblasts.

(B) Remember that live or dead parasites (or larvae) could be

seen in the vascular lesion.

Fig. 57- Photomicrograph of a blood vessel (aorta) showing parasitic

aortitis (parasitic arteritis).Note a cross section of the adult

worm in a fibrous nodule in the wall of the aorta. H&E stain.

X 100.

(4) Acute arteritis: Arteritis occurs as a feature of many infections and

immune-mediated diseases. In inflamed vessel, leukocytes will be

present within and surrounding the walls, and damage to the vessel

wall will be evident as fibrin deposits or necrotic endothelial and

smooth muscle cells. These changes are accompanied by thrombosis

which can result in ischemic injury or infarction in the circulatory

field.

(A) Note the presence of extensive infiltration of leukocytes in

almost all of the layers of the vessel wall.

(B) Engorgement of blood vessel within the vessel wall as well

as hemorrhages could also be seen.

Systemic Pathology (12) : Cardiovascular System

71

Fig. 58- Photomicrograph of a blood vessel showing acute arteritis. Note

the heavy infiltration of inflammatory cells in the wall of the

blood vessel (

BV

) and the presence of blood clot and tissue

debris (

TD

). H&E stain. X 100.

(5) Atherosclerosis: This is a very important vascular disease in human

beings, and it occurs only infrequently in animals. The principal

alteration is accumulation of deposits (atheroma) of lipid, fibrous

tissue, and calcium in vessel walls, which eventually results in

luminal narrowing.

(A) There is increased thickness of the arterial wall due to

accumulation of lipid globules in the cytoplasm of smooth

muscle cells and macrophages (foam cells) in the media

and intima.

(B) There is fibrous tissue accumulation in the arterial wall.

(C) Infiltration of inflammatory cells (mainly macrophages)

could be seen in the affected part of the arterial wall.

BV

TD

Systemic Pathology (12) : Cardiovascular System

72

Fig. 59- Photomicrograph of the wall of a blood vessel (artery) affected

with atherosclerosis. Note the accumulation of lipid globules

in the smooth muscle cells and macrophages (foam cells) in

the media and intima. H&E stain. X 100.

References:

Jones JET. Experimental streptococcal endocarditis in the pig: The

development of lesions 3 to 14 days after inoculation. J Comp

Pathol 1981; 91:51-62.

Jones TC; Hunt RD; King NW. Veterinary Pathology. 6th ed., Philadelphia :

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1997 .

Van Vleet JF, Ferrans VJ. Myocardial disease of animals. Am J Pathol 1986;

124:98-178.

Van Vleet JF, Ferrans VJ. Cardiovascular system. 3rd ed. Tomson's special

Veterinary pathology. St. Louis: Mosby, 2001: 197-2

Systemic Pathology (13) : Urinary System

73

Systemic Pathology (13)

Urinary System

(1) Hydronephrosis: This refers to dilatation of the renal pelvis due to

obstruction of urinary outflow and is associated with increased

pelvic pressure, dilatation of the pelvis, and progressive renal

parenchymal atrophy.

(A) Note dilatation of the renal tubules and degeneration of the

tubular epithelial cells.

(B) Hyaline casts could be seen in the lumens of the tubules.

(C) Note also infiltration of inflammatory cells in the renal

parenchyma.

Fig. 60- Photomicrograph of a kidney affected with hydronephrosis. Note

dilatation of the renal tubules, degeneration of the tubular

epithelium, the presence of hyaline casts, and the infiltration

of inflammatory cells in the renal interstitium. H&E stain. X

40.

(2) Cystic kidney: Polycystic kidneys have many cysts that involve

numerous nephrons such that the kidney can have a (Swiss cheese)

appearance when incised. As cysts enlarge, they compress the

adjacent parenchyma. When kidneys are polycystic, renal function

can be impaired.

Systemic Pathology (13) : Urinary System

74

(A) Multiple cysts could be seen in the kidney.

(B) The cyst wall is lined by flattened epithelial cells.

(C) Note the presence of hyaline casts in the lumens of the

tubules.

(D) Numerous inflammatory cells could be seen in the walls of

the cyst.

Fig. 61- Photomicrograph of a kidney affected with cystic kidney. Note

the presence of multiple cysts (

C

) that are lined by flat cells.

The cysts compress the surrounding tissue. Hyaline cast

(

arrow

) and the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the

renal parenchyma could be seen. H&E stain. X 40.

(3) Focal Interstitial Nephritis: Aggregates of inflammatory cells can

be present in the renal interstitium in various systemic infectious

diseases of domestic animals. When the interstitial inflammation

appears to be the primary lesion and there is no evidence of embolic

nephritis or pyelonephritis, this lesion has traditionally been called

interstitial nephritis. This inflammatory response can be acute,

subacute, or chronic, and is traditionally associated with a

lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, however, other types of leukocytes can

also be present.

(A) Note the accumulation of monocytes, macrophages,

lymphocytes, and plasma cells.

(B) Escherichia coli septicemia in claves can result in

interstitial nephritis (so- called white spotted kidney).

C

C

C

Systemic Pathology (13) : Urinary System

75

Fig. 62- Photomicrograph of a kidney affected with focal interstitial

nephritis. Note the focal accumulation of inflammatory

mononuclear cells in the renal interstitium (

F

). H&E stain. X

100.

(4) Acute Pyelonephritis: This means inflammation of both the renal

pelvis and renal parenchyma and is an excellent example of

supprative tubulointerstitial disease. Infection may be ascending

(most common) via the ureters to the kidney and establish in the

pelvis and inner medulla, or descending (from the kidneys) wherein

bacterial infection of the kidneys occurs via the hematogenous route,

i.e. embolic nephritis.

(A) The transitional epithelium is usually focally or diffusely

necrotic and desquamated. Necrotic debris, fibrin,

neutrophils, and bacterial colonies can be adherent to the

denuded surface.

(B) Medullary tubules are markedly dilated, and their lumina

contain neutrophils and bacterial colonies.

(C) The tubular epithelium is necrotic and an intense

neutrophilic infiltrate, present in the renal interstitium,

can be accompanied by marked interstitial hemorrhages

and edema.

F

Systemic Pathology (13) : Urinary System

76

Fig. 63-Photomicrograph of a kidney affected with acute pyelonephritis.

Note the dilated renal tubules (

blue

arrows

) and heavy

infiltration of the renal interstitium with inflammatory cells

(

red arrows

). H&E stain. X 40.

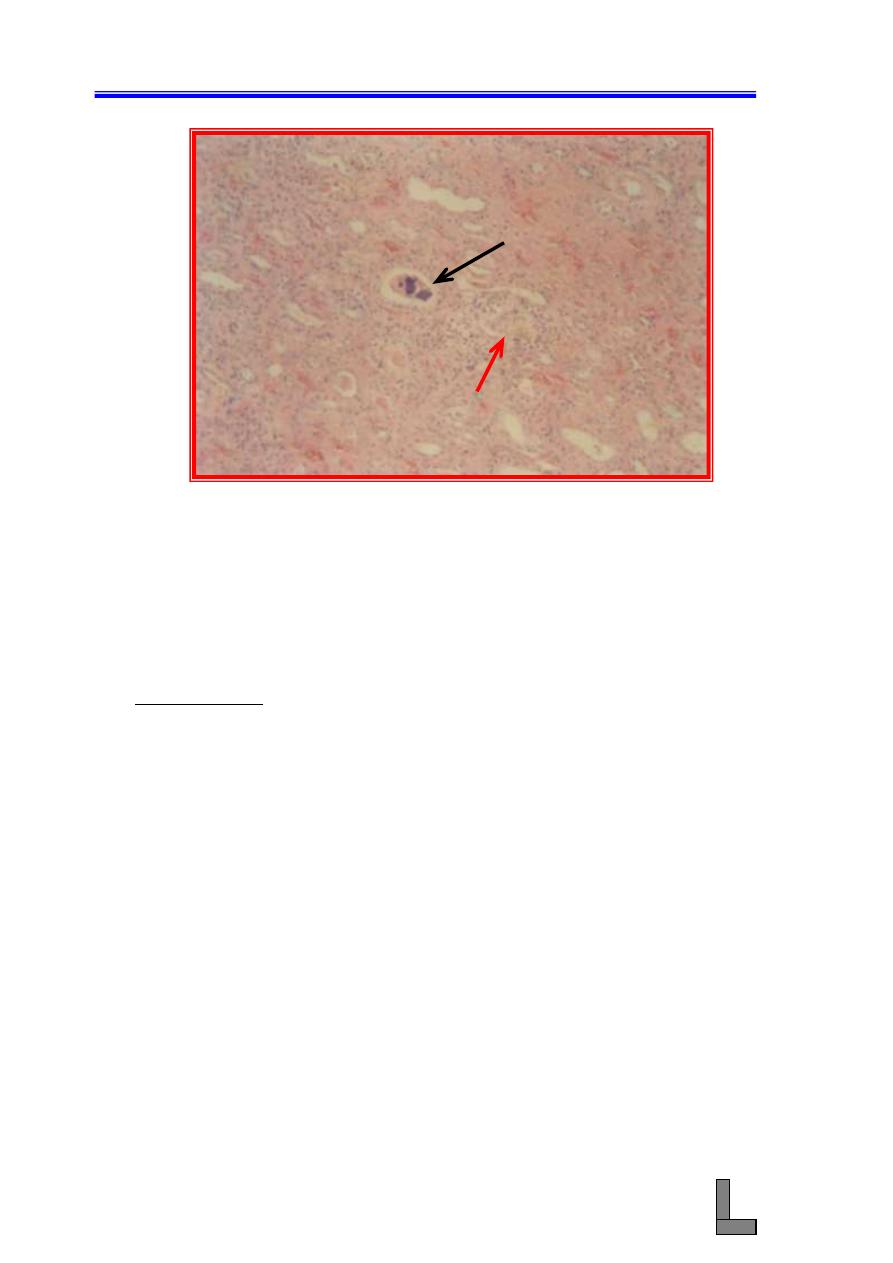

(5) Embolic Nephritis (Suppurative Glomerulitis): This is the result of

a bacteremia, in which bacteria randomly lodge in glomeruli and to a

lesser extent in interstitial capillaries and cause the formation of

multiple foci of inflammation thoughout the renal cortex.

(A) Glomerular capillaries have numerous bacterial colonies.

(B) Necrosis and extensive infiltration with neutrophils often

obliterate the glomeruli.

(C) Glomerular or interstitial hemorrhage can also occur.

(D) With time, the neutrophilic infiltrates will progressively have

increasing numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and

macrophages.

Systemic Pathology (13) : Urinary System

77

Fig. 64- Photomicrograph of a kidney showing embolic nephritis

(suppurative glomerulitis). Note the infiltration of the

glomeruli

with

inflammatory

cells

(

red

arrow

),

hemorrhages in the interstitium, and the presence of a plug

of tissue debris and bacterial colonies in one of the tubules

(black arrow). H&E stain. X 100.

References:

Catran RS, Rennke H, Kumar V. The Kidney and its collecting system. In:

Kumar V, Cotran RS, Robbins SL. Eds. 7th ed. Robbins basic

pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003 : 509

– 542.

Confer AW, Panciera RJ. The urinary system. In: McGavin MD, Carlton WW,

Zachary JF. Eds. 3rd ed. Thomson's special veterinary

pathology. St. Louis : Mosby, 2001 : 235 - 277.

Rebhun WC, Dill SG, Perdrizet JA, Hatfield CE. Pyelonephritis in cows: 15

cases (1982

– 1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc; 1989; 194 : 953 –

955.

Systemic Pathology (14) : Skin and Appendages

78

Systemic Pathology (14)

Skin and Appendages

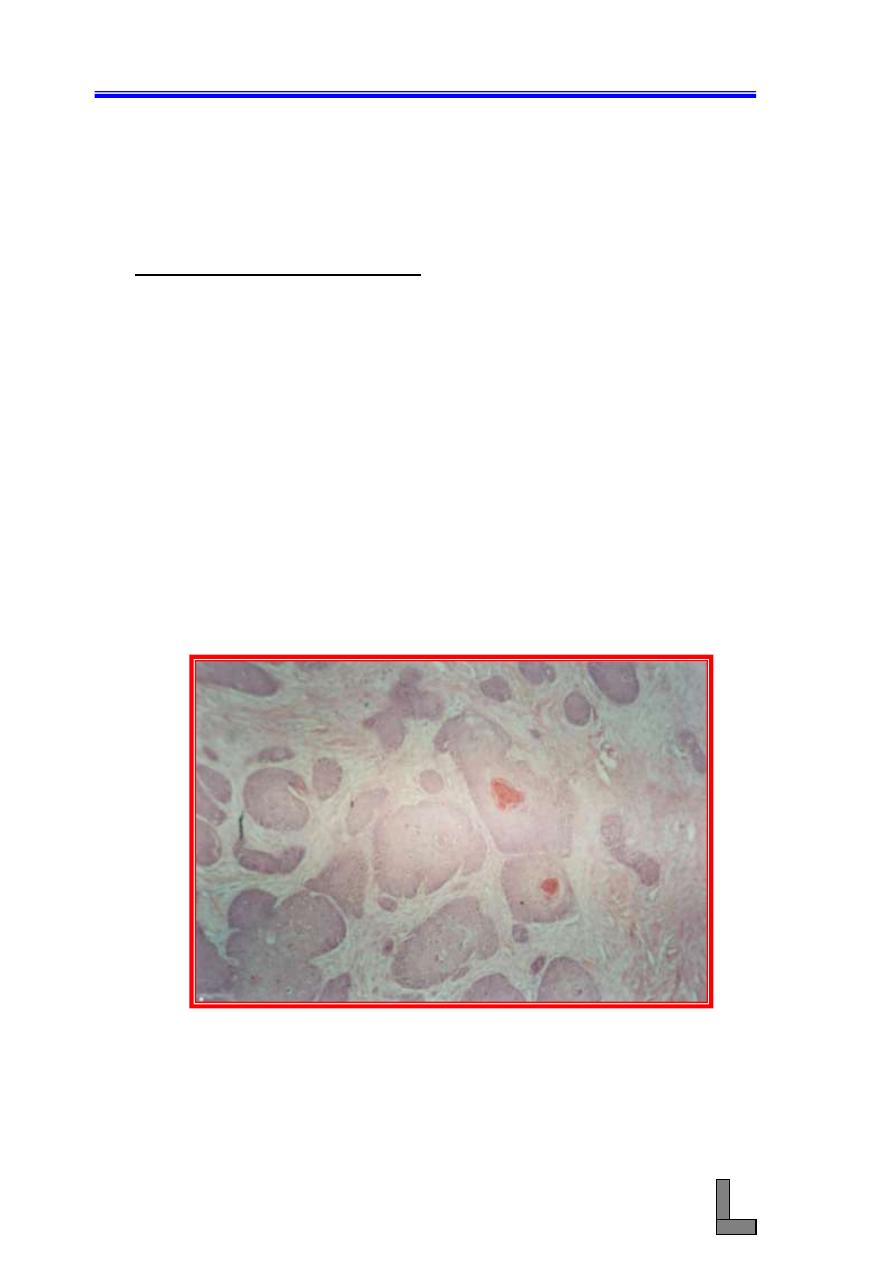

(1) Squamous Cell Carcinoma:- This is a malignant tumor of squamous

epithelial cells and is common in all domestic animals. The tumor

appears grossly as papillary growths of varying size, many of which

have a cauliflower-like appearance. Ulceration and hemorrhages of

the surface of the tumor are common. Another form of the tumor

(the erosive form) is characterized by the appearance of shallow,

crusted ulcer which, if allowed to develop, can become deep and

craterlike.

(A) The tumor consists of irregular masses or cords of epidermal

cells that proliferate downward and invade the dermis and

subcutis.

(B) This tumor is well – differentiated since large numbers of "horn

pearls" (cancer pearls) are present and they consists of

concentric layers of sequamous cells showing gradually

increasing keratinization toward the centers.

(C) Mitotic figures are abundant and many of them are atypical.

Fig. 65- Photomicrograph of a skin affected with squamous cell

carcinoma. Neoplastic cells could be seen invading the

dermis in the form of finger-like projections or nests. Some

of the nests contain keratin. H&E stain. X 100.

Systemic Pathology (14) : Skin and Appendages

79

(2) Dermatitis: Dermatitis is an inflammation of the skin, and it could be

serous, papular, suppurative, necrotic, or parasitic. Other types of

dermatitis are also exist. Among the non-infectious causes of

dermatitis are solar energy, photosensitization, chemical causes,

immunological causes, temperature extremes, bites, and others. The

common infectious causes include poxvirus, herpesviruses,

rickettsial infections, bacteria, fungi, parasites, metabolic disorders,

and nutritional causes.

(A) This is a section of the skin stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Note ulceration of the skin (necrosis and sloughing of the

epidermis).

(B) Note the increased thickness of the dermis due to the infiltration

of inflammatory cells and proliferation of local fibrocytes.

Fig. 66- Photomicrograph of a skin showing dermatitis. note the heavy

diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells into the dermis (

D

).

Small portions of the epidermis could also be seen (

arrows

).

H&E stain. X 100.

(3) Parasitic Dermatitis: Ectoparasites that cause cutaneous lesions

include mites and ticks (have eight legs), and lice, and flies, (have

six legs). Endoparasites that cause lesions include nematodes,

trematodes, and protozoa. Cutaneous lesions that result from

parasitic infections depends on the parasite number, location, feeding

habits, and host immune response.

D

Systemic Pathology (14) : Skin and Appendages

80

(A) This is a section of the skin stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Note the presence of many parasitic nodules in the epidermis

and dermis.

(B) Each nodule consists of a section in the parasite surrounded by

many mixed – type inflammatory cells (eosinophils, mast cells,

neutrophils, lymphocytes and macrophages).

(C) Hyperemia and hemorrhages could also be seen.

Fig. 67- Photomicrograph of a skin affected with parastitic dermatitis.

Note heavy infiltration of the dermis with mixed type

inflammatory cells and the presence of a parasitic nodule

(

arrow

). H&E stain. X 100.

References:

Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ. Veterinary dermatopathology: a macroscopic

and microscopic evaluation of canine and feline skin disease. St.

Louis : Mosby

– Year Book, 1992.

Hargis AM, Ginn PE. Integumentary system. In: McGavin MD, Carlton WW,

Zachary JF. Eds. 3rd ed. Thomson's special veterinary

pathology. St. Louis : Mosby, 2001 : 537-599.

Stannard AA, Pulley LT. Tumors of the skin and soft tissues. In: Moulton JE,

ed. Tumors in domestic animals. 3rd ed. Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1990: 23-87.

Yager JA, Scott DW. The skin and appendages. In: Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC,

Palmer N, eds. Pathology of domestic animals. 4th ed. New

York : Academic Press, 1993: 531-738.

Systemic Pathology (15) : The Musculo-Skeletal System

81

Systemic Pathology (15)

The Musculo – Skeletal System

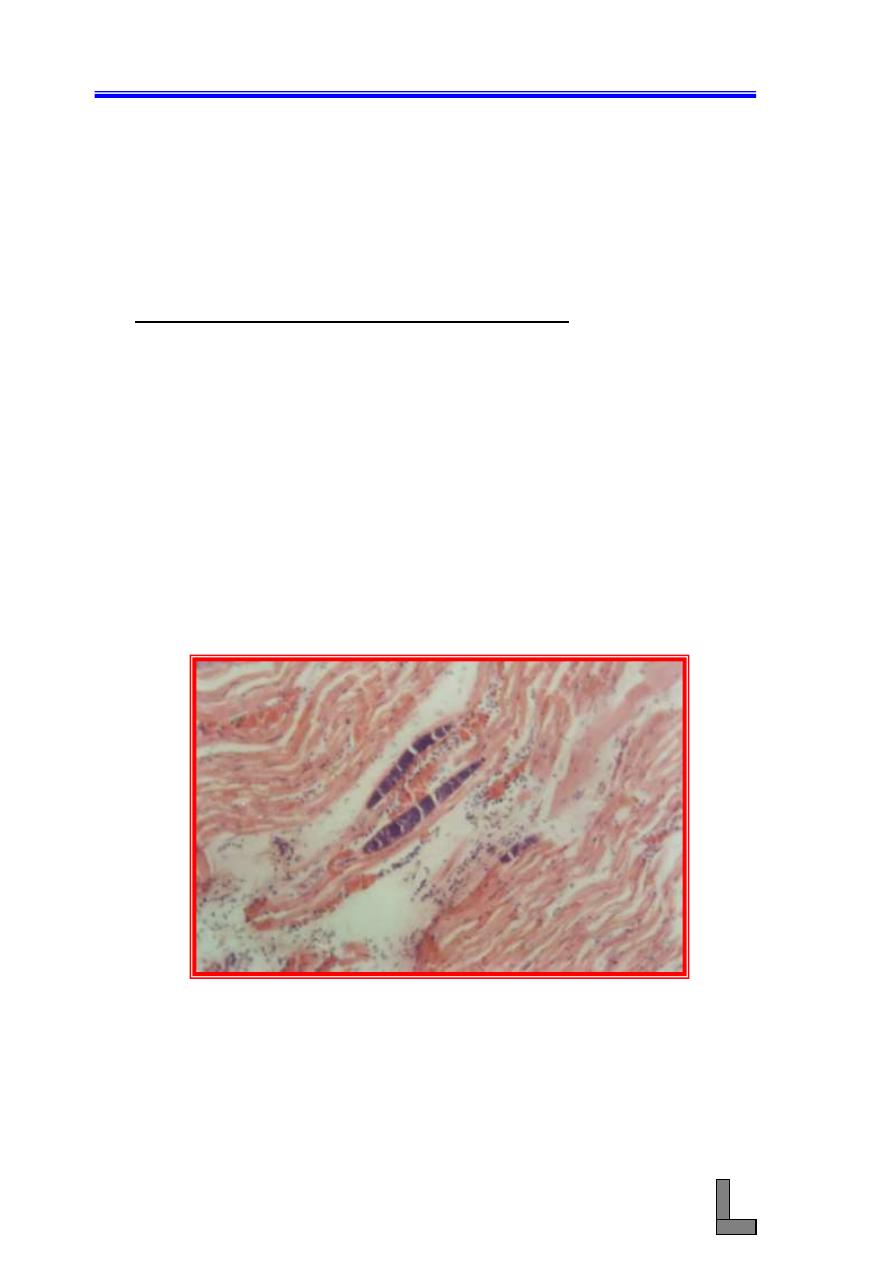

(1) Parasitic Myositides (Sarcocystis Infection):Parasitic infections of

the skeletal muscle of domestic animals include sarcocystis sp. (in

cattle, sheep, goats), Neosporum caninum (in dogs), and Trichinella

spiralis (in pigs). Sarcocystis spp occur as intracytoplasmic protozoal

cysts. Because they are intracellular, they are protected from the host's

defense mechanisms and thus, there is no inflammatory response or

reaction by the myocyte. Eosinophilic myositis may occur in cattle as

a manifestation of Sarcoystis infection and this may involve

hypersensitivity.

(A) Rounded and elongated parasitic cysts could be seen in myofibers

without the occurrence of inflammation.

(B) Atrophic muscle fibers are separated by an exudate consisting

chiefly of eosinophils.

Fig. 68- Photomicrograph of a skeletal muscle showing parasitic

myositides (Sarcocystis infection). Elongated parasitic cysts

could be seen in the myofibers. A mild inflammatory

exudates could also be seen between the bundles of muscle

fibers. H&E stain. X 100.

Systemic Pathology (15) : The Musculo-Skeletal System

82

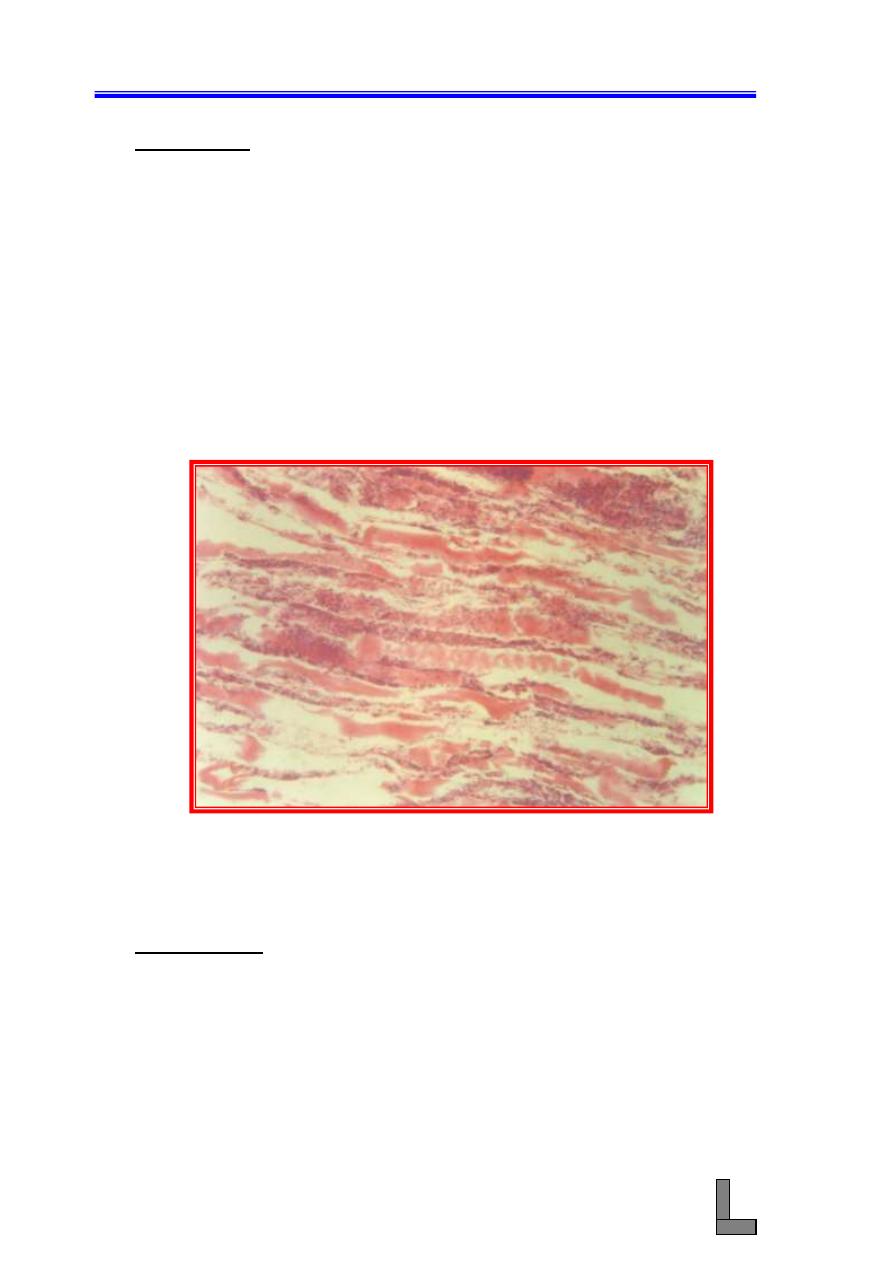

(2) Nutritional Myopathy: This condition also called white muscle

disease and it is common in calves, lambs,, and horses. It is due to

vitamin E and selenium deficiency. Grossly, numerous gray and white

streaks which are areas of segmental necrosis and calcification could

be seen. Necrotic portions of the fiber may become floccular or

granular as that portion of the myofiber starts to fragment. The

adjacent histologically normal portion of the myofiber can separate

from the necrotic segement, forming so – called retraction caps.

Occasionally, necrotic segments of myofibers are mineralized.

(A) This is a section in skeletal muscle stained with hematoxylin and

eosin. Segmental necrosis of the myofibers could be seen.

(B) Calcification of the necrotic myfibers could also be seen.

Fig. 69- Photomicrograph of a skeletal muscle of a case of nutritional

myopathy. Note necrosis, disappearance, and replacement of

bundles of muscle fibers by fibrous tissue. Some atrophied

bundles of muscle fibers could also be seen. H&E stain. X

100.

Systemic Pathology (15) : The Musculo-Skeletal System

83

(3) Myositis: This is inflammation of muscle (plural: myositides) and is

caused by a wide array of agents (bacteria , viruses, protozoa,

helminths, and immuno-mediated mechanisms). In true myositis the

inflammatory cells are directly responsible for initiating and

maintaining myofiber injury. The types of inflammation could be

suppurative, serohemorrhagic, or granulomatous.

(A) The necrotic segment is infiltrated by macrophages which " clean

– up" the cellular debris.

(B) Severe acute necrotizing myopathy is accompanied by a certain

degree of infiltrating lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and

even eosinophils.

(C) Cytokines released from damaged muscle fibers recruit a variety

of inflammatory cells.

Fig. 70- Photomicrograph of a skeletal muscle showing myositis. Note

the presence of accumulation of inflammatory cells between

the bundles of muscle fibers. H&E stain. 40X.

References:

Carpenter JL, Schmidt CM, Moore FM, Albert DM, Abrams KL, Elner VM.

Canine bilateral extraocular polymyositis. Vet Pathol 1989; 26 :

510 - 512.

Hulland TJ. Muscle and tendon. In : Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, eds.

Pathology of domestic animals. 4th ed. New York : Academic

press, 1993 : 183

– 265.

McGavin MD, Carlton WW, Zachary JF. Eds. 3rd ed. Thomson's special

veterinary pathology. St. Louis : Mosby, 2001 : 474 - 477.

Systemic Pathology (16) : The hemic and lymphatic System

84

Systemic Pathology (16)

The Hemic and Lymphatic Systems

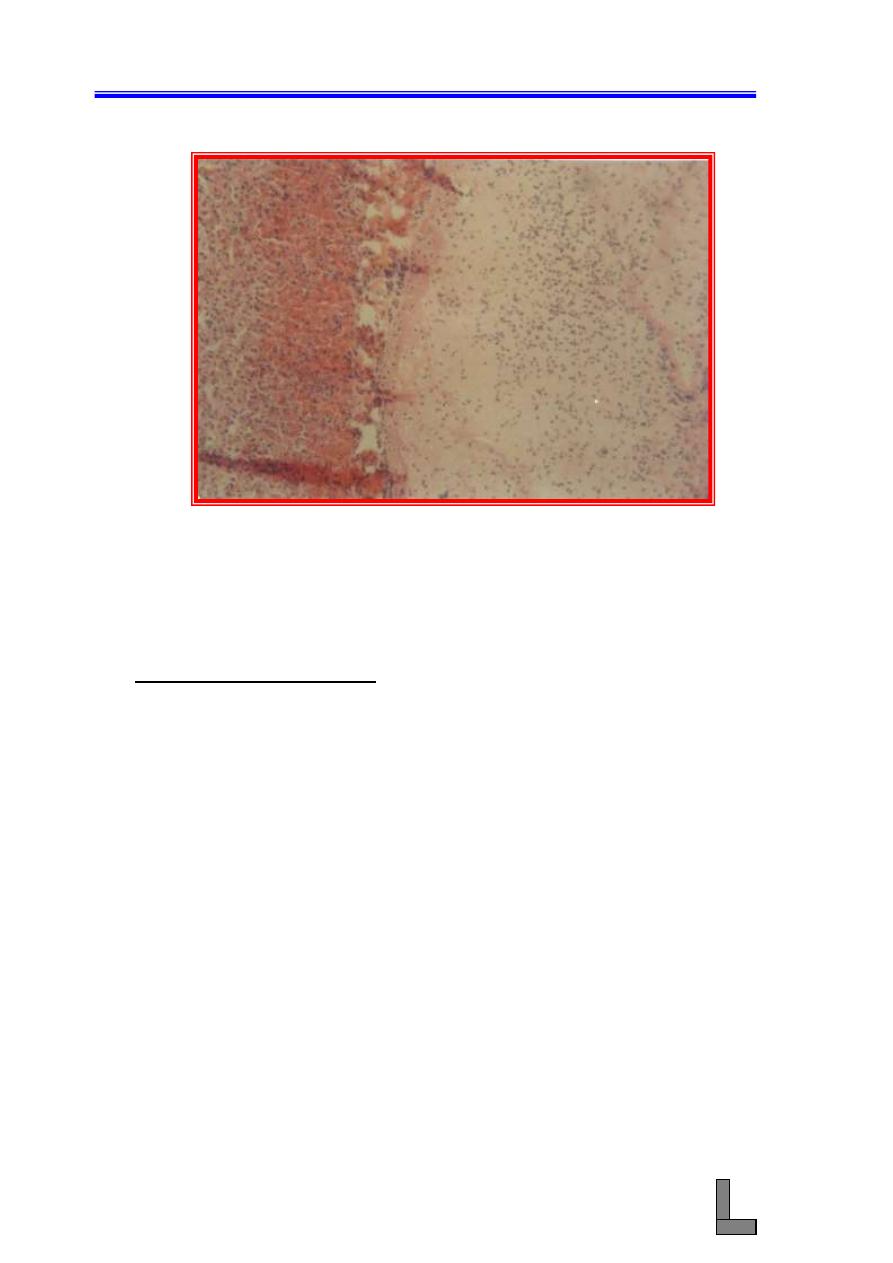

(1) Chronic Focal Suppurative Splenitis: chronic splenitis occurs in

many infectious diseases, and leads either to a diffuse enlargement

or irregular enlargement (nodular) depending on the causative

organism. Examples of infectious diseases causing chronic splenitis

include brucellosis, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, histoplasmosis,

tularemia,

caseous

lymphadenitis,

pseudotuberculosis,

and

leishmaniasis. Lymphoid hyperplasia occurs in many of these

diseases and contributes to hypersplenism.

(A) this is a section in the spleen stained with hematoxylin and

eosin. Note the presence of multiple foci of inflammation in the

splenic parenchyma.

(B) Each focus consists of a central area of necrosis (liquefactive

necrosis)

surrounded

by

inflammatory

cells

(mainly

neutrophils) and then mononuclear cells (lymphocytes, plasma

cells, and macrophages) and finally by a thick connective tissue

capsule.

(C) Hemorrhages and deposition of hemosiderin pigment could also

be seen.

Fig. 71- Photomicrograph of a spleen showing chronic focal suppurative

splenitis. Multiple foci of suppurative inflammation could be

seen. H&E stain. X 40.

Systemic Pathology (16) : The hemic and lymphatic System

85

(2) Leukosis (liver): Avian leucosis complex is an economically

important disease in the domestic fowl. Two main forms of the

disease are known and they include lymphatic leukosis and

myelocytic leukosis. Lymphocytic leukosis occurs in one of 5 forms

: neural, visceral, ocular, osteopetrotic and skin forms. The visceral

form of the disease is characterized by a diffuse or localized

infiltration of lymphoid cells in any of the visceral organs.

(A) This is a section in the liver stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Note the presence of densely packed collections of lymphoid

cells having the appearances of immature lymphocytes.

(B) Large areas within the liver have been replaced by the neoplastic

cells.

Fig. 72- Photomicrograph of a liver of a chicken affected with leucosis.

Densely packed collections of neoplastic lymphoblasts could

be seen in the hepatic parenchyma. Only remnants of

hepatocytes could be found (arrows). H&E stain. X 100.

(3) Lymphosarcoma: This type of neoplasms is also called lymphoma or

malignant lymphoma and it is a common neoplasm in animals. The

tumor arises from lymphocytes which are present in lymphoid tissue

anywhere in the body. Many cytological forms of lymphosarcoma

are known. Microscopically, the neoplastic cells cause disappearance

of the normal architecture of the involved lymphoid organ.

(A) This is a section of lymph node stained with hematoxylin and

eosin. Note disappearance of the normal architecture of the

Systemic Pathology (16) : The hemic and lymphatic System

86

lymph node due to the presence of numerous pleomorphic

neoplastic cells and mitotic figures.

(B) The tumor cells have replaced the normal lymphoid tissue of the

node.

Fig . 73- Photomicrograph of a lymph node affected with lympho

sarcoma. Note that large number of neoplastic

lympoblasts obscuring the normal architecture of the

lymph node. H&E stain. X 100.

(4) Acute Serous Lymphadenitis: The most common causes of

lymphadenitis are infectious agents or their products. In most

examples, there is an associated reactive hyperplasia. Although there

are many specific diseases which affect lymph nodes, many

examples of lymhadenitis are nonspecific. Lymhadenitis occurs in

nodes draining primary inflammatory disease of other organs or

tissues. In this type of lymphadenitis, hyperplasia and edema with

distension of the lymph sinuses are seen. The distended sinuses

contain a variable number of neutrophils and macrophages.

Eosinophils are seen in large numbers in lymph nodes draining

chronic skin disease and hypersensitivity lesions.

(A) this is a section of lymph node stained with hematoxylin and

eosin. Note the vascular and cellular changes typical of

inflammation.

(B) A serous exudate stained pink could be seen particularly

underneath the capsule.

Systemic Pathology (16) : The hemic and lymphatic System

87

(C) The exudate consists mainly of serous fluid. Polymorphonuclear

leukocytes could also be seen.

Fig. 74- Photomicrograph of a lymph node affected with acute serous

lymphadenitis. A pinked colored serous exudates and

numerous

polymorphonnuclear

leukocytes

could

be

visualized between the lymph follicles and under the

capsule. H&E stain. X 100.

(5) Leukosis in kidneys: See the description given to slide No. 2

(A) Large numbers of neoplastic lymphoblasts could be seen

infiltrating the renal interstitium.

(B) The tumor cells have replaced the normal renal tissue and caused

distortion of the normal architecture of the kidney.

Systemic Pathology (16) : The hemic and lymphatic System

88

Fig. 75- Photomicrograph of a kidney affected with leucosis. Nnumerous

neoplastic lymphoblasts have infiltrated the renal

interstitium. Note distortion of the normal architecture of the

kidney. H&E stain. X100.

(6) Leukosis in Spleen : See the description given to slide No. 2

(A) This is a section in spleen stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Note the numerous pleomorphic lymphoblasts infiltrating the

spleen.

(B) Mitotic figures and lymphoid hyperplasia could also seen.

Systemic Pathology (16) : The hemic and lymphatic System

89

Fig. 76- Photomicrograph of a spleen affected with leucosis. Note diffuse

infiltration of neoplastic lymphoblasts in the splenic

parenchyma. H&E stain. X 100.

References:

Jones TC; Hunt RD; King NW. Veterinary Pathology. 6th ed. Philadelphia :

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins ; 1997 : 1009

– 1042.

McGavin MD ; Carlton WW; Zachary JF. Thomson's special veterinary

pathology. 3rd ed. St. Louis : Mosby ; 2001 : 325

– 379.

Systemic Pathology (17) : Male Reproductive System

90

Systemic Pathology (17)

Male Reproductive System

(1) Granulimatous orchitis: Orchitis means inflammation of the testicle

and in bulls Brucella abortus is probably the most important

example of granulomatous orchitis in domestic animals. This type of

orchitis includes the formation of multiple, possibly coalescing,

inflammatory nodules displacing and replacing the testicular

parenchyma. In most of the cases bacteria are seen microscopically

clustered in the cytoplasm of macrophages in the areas of

pyogranulomatus inflammation.

(A) Note the presence of several infectious granulomas, each

consists of a necrosis center with calcification, surrounded by

inflammatory cells (mononuclear cells) and giant cells.

(B) The whole lesion is surrounded by a thick connective tissue

capsule.

Fig. 77- Photomicrograph of a testis affected with granulomatous

orchitis. Note degeneration and necrosis of the seminiferous

tubules (black arrows) and one tubule is containing pus and

surrounded by fibrous tissue (

red arrow

). H&E stain. X

100.

Systemic Pathology (17) : Male Reproductive System

91

(2) Testicular Degeneration: This condition can be unilateral or

bilateral, depending on whether the cause is local or systemic.

Among the common causes of this condition are fever, local heat,

obstruction of flow of spermatozoa, torsion or severe crushing of the

spermatic cord, nutritional deficiency, hormonal aberrations, toxins,

and irradiation.

(A) The seminiferous tubules are small and have thickened basement

membrane, decreased numbers of seminiferous epithelial cells,

vacuolated Sertoli cells, intratubular giant cells, and interstitial

fibrosis.

(B) Impaction of sperms may or may not be seen as it depends on

whether obstruction of the seminiferous tubules present or not.

Fig. 78- Photomicrograph of a testis affected with degeneration and

atrophy. Note the small size of the seminiferous tubules and

their irregular shape. H&E stain. X 40.

(3) Spermatic granuloma: Epididymitis can be focal, multifocal,

diffuse, unilateral or bilateral. In non-infectious epididymitis,

spermatozoa that escape from the lumen of the epididymis incite a

foreign body response. Congenital and acquired obstructions of the

epididymal tubule is the main cause of escape of spermatozoa.

(A) Sperms that have escaped from the lumen of the duct of the

epididymis are surrounded by inflammatory cells particularly

phagocytic cells, including multinucleated giant cells.

(B) The whole lesion is surrounded by fibrous tissue.

Systemic Pathology (17) : Male Reproductive System

92

Fig. 79- Photomicrograph of a testis affected with spermatic granuloma.

Note the granulomatous reaction (

G

) and the thick fibrous

tissue surrounding the granuloma (F).H&E stain. X 100.

(4) Suppurative Orchitis: Among the most common organisms that

cause infectious orchitis in domestic animals are Actinomyces

pyogenes, Bluetongue virus, Brucella abortus, lumpy skin disease

virus, Mycobacterium tunberculosis, and Nocardia asteroides in

bulls, Brucella melitensis in bucks, Brucella canis, canine distemper

virus, Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, and Pseudomonas

pseudomallei in dogs, Brucella ovis, Chlamydia psittaci,

Corynebacterium ovis, and sheep pox virus in rams, equine infectius

anemia virus, equine viral arteritis virus, Salmonella abortus equi,

and Strongylus edentatus in stallions. It starts as inflammation in the

seminiferous tubules, which then spills over into the interstitium.

(A) Note that many of the seminiferous tubules have undergone

atrophy and coagulative necrosis.

(B) Neutrophilic exudate could be seen in the lumen of the tubules as

well as in the interstitial connective tissue.

F

G

F

Systemic Pathology (17) : Male Reproductive System

93

Fig. 80 -

Photomicrograph of the testis of a donkey affected with

suppurative orchitis. Note extensive destruction of the

testicular tissue, disappearance of the seminiferous tubules,

and the presence of edema and heavy infiltration of

neutrophilic exudate. H&E stain. X 100.

References:

Humphery JD; Ladds PW. Pathology of the bovine testis and epididmyis. Vet

Bull 1975; 45: 787-795.

McEntee K. Pathology of the testis of the bull and stallion. Proc Soc

Theriogenol 1979; 80-91.

McGavin MD; Carlton WW; Zachary JF. Thomson's special veterinary

pathology. 3 rd. ed. St. Louis : Mosby; 2001 : 635-652.

Systemic Pathology (18) : The Female Reproductive tract

94

Systemic Pathology (18)

The female Reproductive Tract

(1) Salpingitis:- This means inflammation of the uterine tubes and it

results from spread of infection from the uterus to the uterine tubes,

and it is usually bilateral. The inflammation ranges from mild to

severe and from acute to chronic, and even mild inflammation can

reduce fertility.

(A) This is a section of the uterine tube stained with hematoxylin and

eosin. Note that the lamina propria of the folds of the uterine

tube is hypercellular and is infiltrated by inflammatory cells

(mainly mononuclear cells).

(B) The lumen of the tube contains inflammatory exudate that

includes many neutrophils.

(C) Hyperemia of blood vessels in the wall of the uterine tube culd

also be seen.

Fig. 81-

Photomicrograph of a uterine tube (oviduct) showing

salpingitis. Note hyperemia and the infiltration of

inflammatory cells in the wall of the tube. H&E stain. X 100.

Systemic Pathology (18) : The Female Reproductive tract

95

(2) Oophoritis:- This condition means inflammation of the ovary and it

is quite rare in domestic animals. Viral infection such as infectious

bovine rhiontracheitis and bovine virus diarrhea are accompanied with

oophoritis when these viral diseases are induced experimentally.

Necrotizing oophoritis is the most common type of oophoritis.

(A) The lesions in the corpus luteum range from focal necrosis and

infiltration of mononuclear cells to diffuse hemoorhage and

necrosis.

(B) Affected ovaries also have necrotic follicles and diffuse

mononuclear cell infiltrates in the stroma.

Fig. 82-

Photomicrograph of an ovary affected with oophoritis. Portion

of a secondary follicle and corpus luteum could be seen.

mononuclear cells could be seen in the ovarian interstitium.

H&E stain. X 100.

(3) Papillary Cystadenoma: Adenoma in its pure state is uncommon and

is usually a part of mixed tumor. In its pure state, the tumor is usually

occurs as papillary adenoma with dilated ducts and arising in multiple

sites within the gland. The tumor develops within the lobules from the

alveoli (and / or intralobular ducts system), in the interlobular ducts, or

in the teat sinus.

(A) This is a section of the mammary gland stained with hematoxylin

and eosin. Note conversion of the glandular alveoli to cystic

structures.

(B) Cystic spaces containing papillary ingrowths are seen.

Systemic Pathology (18) : The Female Reproductive tract

96

(C) Greatly dilated ducts containing papillomatus growths could also

seen.

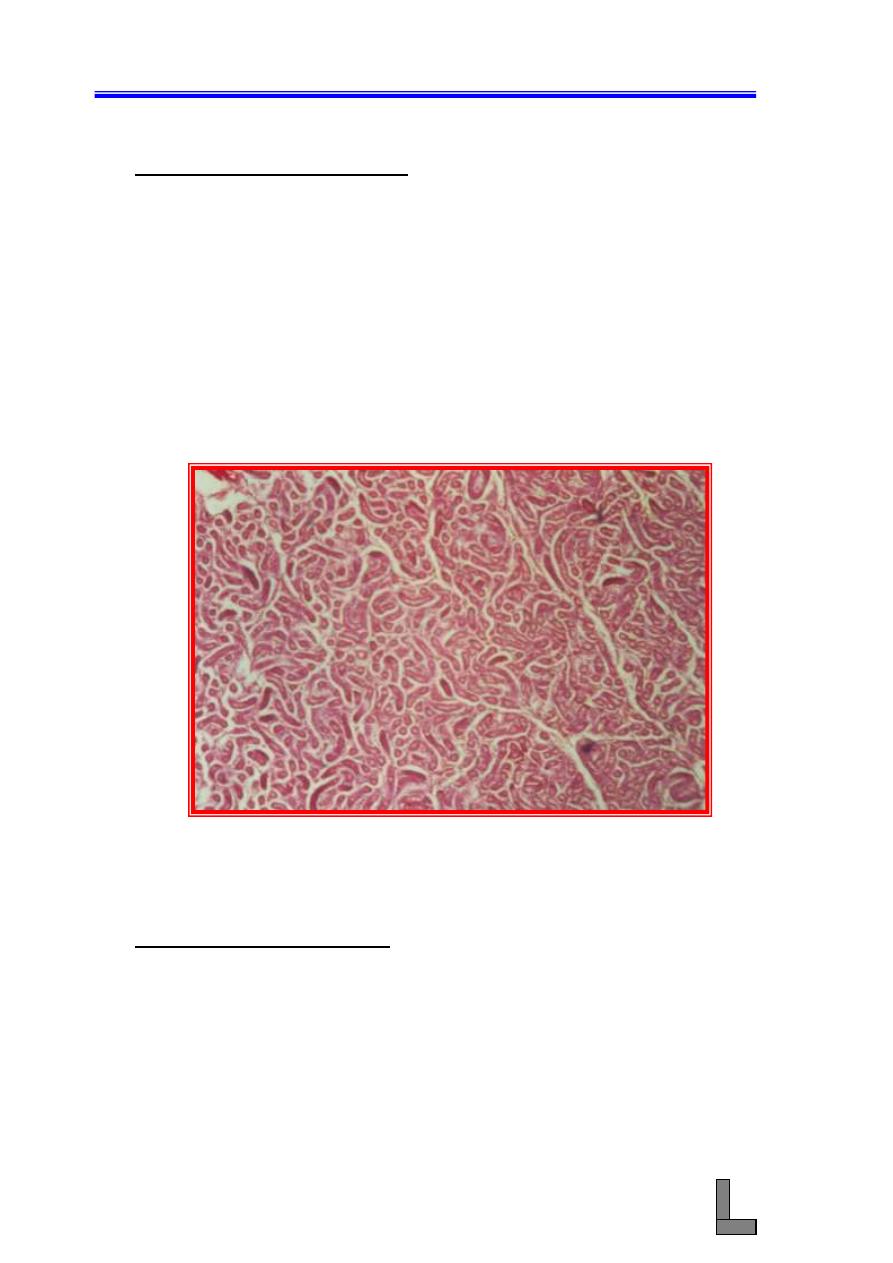

Fig. 83-

Photomicrograph of a mammary gland affected with

cystadenoma. Note cystic dilatation of some of the acini and

papillary projections of the lining epithelium of some other

acini.. H&E stain. X 100.

(4) Endometritis: This is inflammation that is limited to the

endometrium. All cases of uterine infections beign as endometritis.

Uterine infections are related to introduction of semen contaminated

with bacteria or to metabolic disturbances that favor an environment

for bacterial organisms in pregnancy, parturition, or postpartum

involution.

(A) A few to many neutrophils are found in the stroma and in the

glands.

(B) A rang of surface changes from desquamation of a few surface

epithelial cells to severe necrosis of the endometrium.

(C) Moderate endometrial fibrosis could also be seen.

Systemic Pathology (18) : The Female Reproductive tract

97

Fig. 84-

Photomicrograph of a uterus affected with endometritis. Note

the heavy infiltration of mononuclear cells ( particularly

lymphocytes) in the endometrium H&E stain. X 100.

References:

Gelberg HB; McEntee K. Pathology of the canine and feline uterine tube. Vet

Pathol 1986; 23:770-775.

Herenda D. An abattoir survey of reproductive organ abnormalities in beef

heifers. Can Vet J 1987; 28: 33-37.

McGavin Md; Carlton WW; Zachary JF. Thomoson's special Veterinary

Pathology. 3 rd. ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001: 601-652.

Systemic Pathology (19) : The Endocrine System

98

Systemic Pathology (19)

The Endocrine System

(1) Lymphocytic Thyroiditis: The spontaneous lymphocytic thyroiditis

is seen in dogs, laboratory rats, and monkeys; and it closely resembles

Hashimoto thyroiditis in human beings. The immunologic basis of the

development of chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis in both human beings

and dogs appears to be through production of autoantibodies usually

directed

against

thyroglobulin

or

a

microsomal

antigen

(thyroperoxidase) and infrequently against the TSH receptor protein,

nuclear antigen, and a second colloid antigen from follicular cells.

(A) Multifocal to diffuse infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and

macrophages and, sometimes, lymphoid nodules are evident.

(B) Thyroid follicles are small and lined by columnar epithelial cells;

lymphocytes, macrphages, and degenerate follicular cells are

often present in vacuolated colloid.

(C) Thyroid C cells are present as small nests or nodules between

follicles.

Fig. 85 -

Photomicrograph of a thyroid gland showing lymphocytic

thyroiditis. Note the heavy infiltration of lymphocytic

exudate between the thyroid follicles. H&E stain. X 100.

Systemic Pathology (19) : The Endocrine System

99

(2) Goiter: Goiter means non-inflammatory and nonneoplatic

enlargement of the thyroid gland. The condition could be

accompanied by either hypo-or hyperthyroidism, or compensated

function. Three general causes exist for goiter: (1) iodine deficiency,

(2) goitrogens, and (3) hereditary biosynthetic defects of thyroid

hormones. Three types of goiter are known to occur: (1) simple goiter

(hyperplastic goiter, colloid goiter, diffuse nontoxic goiter), (2)

Multinodular

goiter

(adenomatous

goiter,

nodular

thyroid

hyperplasia), and (3) exophthalmic goiter (goiter of hyperthyroidism,

toxic goiter, Grave's disease). In simple goiter, the thyroid is

uniformaly enlarged grossly. The microscopical changes include:

(A) The presence of large follicles with colloid, which is lined by

flattedened epithelium.

(B) A great variation in the size of the follicles, and some may retain

papillary projections into the lumens.

Fig. 86 -

Photomicrograph of a thyroid gland from a case of goiter.

Note the variation in the size of the colloidal follicles and the

large quantity of colloidal material in each follicle. H&E

stain. X 100.

References:

Capen CC. Endocrine system. In: McGavin MD, Carlton WW, Zachary JF.

Eds. 3rd ed. Thomson's special veterinary pathology. St. Louis :

Mosby, 2001 : 295 - 305.

Gosselin SJ, Capen CC, Martin SL, Krakowka S. Autoimmune lymphocytic

thyroiditis in dogs. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 1982; 3: 185

–

201.

Jones TC; Hunt RD; King NW. Veterinary Pathology. 6th ed. Philadelphia :

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins ; 1997 : 1236-1237.

Systemic Pathology (20) : Nervous System

100

Systemic Pathology (20)

Nervous System

(1) Spongy Degeneration: This is a group of diseases of young animals

characterized by a spongy lesion (status spongiosus). This lesion can

develop by several different mechanisms that include splitting of the

myelin sheath, accumulation of extracellular fluid, swelling of cellular

(e.g. astrocytic, neuronal) processes, and axonal injury (e.g. Wallerian

degeneration) when swollen axons are no longer detectable within

distended spaces.

(A) Variabley sized empty spaces within the white matter could be

seen.

(B) There is a defect in the formation of myelin.

Fig. 87 -

Photomicrograph of a brain exhibiting spongy degeneration

(status spongiosus). Note the presence of variably sized

empty spaces. H&E stain. X 100.

Systemic Pathology (20) : Nervous System

101

(2) Listeriosis: This is a bacterial infection with particular affinity to

cause CNS disease, mainly in domestic ruminants. Infections also

occur in human beigns. Three forms of the disease are known to occur

and they include meningoencephalitis, abortion and stillbirth, and

septicemia, the later commonly develops in young animals, possibly

from an in utero infection. The encephalitic and genital forms of the

disease rarely occur together in an individual animal or in the same

flock or herd.

(A) The lesion consists of clusters of microglia and variable numbers

of neutrophils. Macrophages, gitter cells, and necrosis could also

be seen.

(B) Gram – positive bacilli can be detected in some lesions.

Fig. 88 -

Photomicrograph of a brain showing microabscesses in the

brain (Listeriosis). Note the presence of focal accumulation

of neutrophils and loss of parenchyma. H&E stain. X 100..

Rferences:

Charlton KM, Garcia MM. Spontaneous listeric encephalitis and neuritis in

sheep. Vet Pathol 1977; 14: 297

– 313.

Storts RW, Montgomery DL. The nervous system. In: McGavin MD, Carlton

WW, Zachary JF. Eds. 3rd ed. Thomson's special veterinary

pathology. St. Louis : Mosby, 2001 : 381

– 459.