Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABMLecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

2016

learning-topics

Ageing and diseaseHistory

• Slow down the pace.• Ensure the patient can hear.

• Establish the speed of onset of the illness.

• If the presentation is vague, carry out a systematic enquiry.

• Obtain full details of:

all drugs, especially any recent prescription changes

past medical history, even from many years previously

usual function

1. Can the patient walk normally?

2. Has the patient noticed memory problems?

3. Can the patient perform all household tasks?

• Obtain a collateral history:

confirm information with a relative or carer and the general practitioner, particularly if the patient is confused or communication is limited by deafness or speech disturbance.

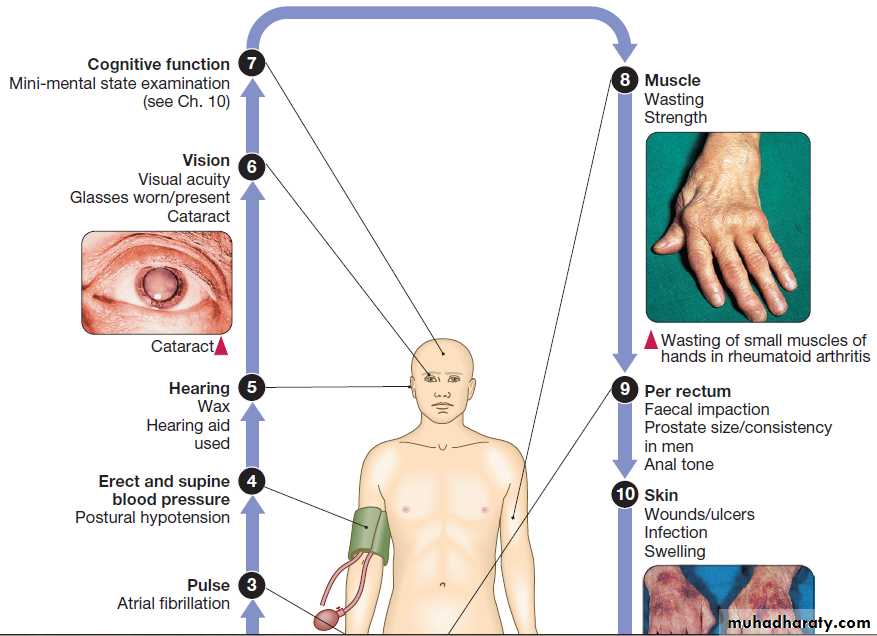

Examination

• Thorough to identify all comorbidities.

• Tailored to the patient’s stamina and ability to cooperate.

• Include functional status:

cognitive function

gait and balance

nutrition

hearing and vision.

Social assessment

Home circumstances• Living alone, with another or in a care home.

Activities of daily living (ADL)

• Tasks for which help is needed:

domestic ADL: shopping, cooking, housework

personal ADL: bathing, dressing, walking.

• Informal help: relatives, friends, neighbours.

• Formal social services: home help, meals on wheels.

• Carer stress.

The older population is extremely diverse; a substantial

proportion of 90-year-olds enjoy an active healthy

life, while some 70-year-olds are severely disabled by

chronic disease. The terms ‘chronological’ and ‘biological’

ageing have been coined to describe this phenomenon.

Biological rather than chronological age is taken

into consideration when making clinical decisions about,

extent of investigation and intervention that is appropriate.

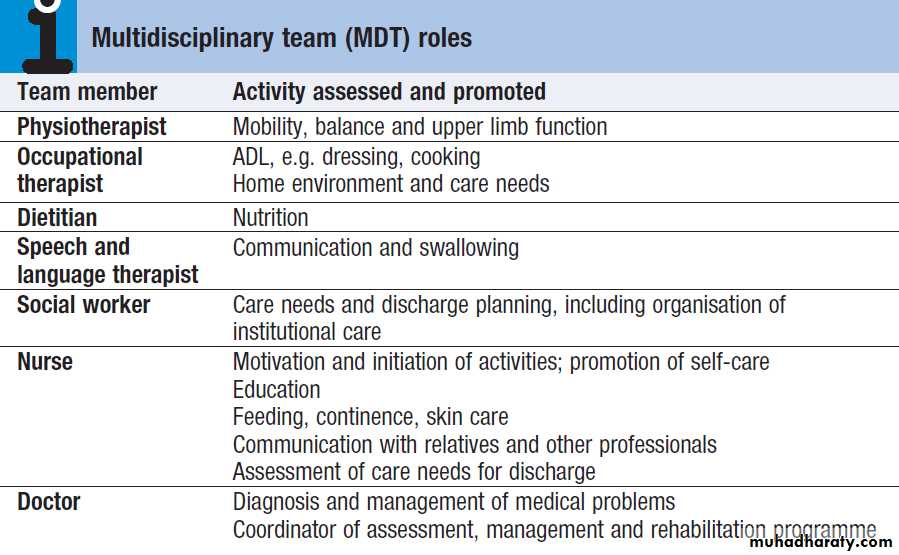

Geriatric medicine is concerned particularly with frail old, in whom physiological capacity is so reduced that they are incapacitated by even minor illness. They frequently have multiple comorbidities, and acute illness may present in non-specific ways, such as confusion, falls or loss of mobility and day-to-day functioning. These patients are prone to adverse drug reactions, partly because of polypharmacy and partly because of age-related changes in responses to drugs and their elimination . Disability is common, but patients’ function can often be improved by the interventions of the multidisciplinary team .

Older people have been neglected in research terms

and, until recently, were rarely included in randomisedcontrolled clinical trials.

There is thus little evidence on which to base practice.

DEMOGRAPHY

The demography of developed countries has changed

rapidly in recent decades.

In the UK, for example, the total population grew by 11% over the last 30 years, but the number of people aged over 65 years rose by 24%. The steepest rise occurred in those aged over 85 – from 600 000 in 1981 to 1.5 million in 2011 – and this number is projected to increase to 2.4 million by 2026, whilst the working-age population (20–64 years) is expected to grow by only 4% between 2011 and 2026.

This will have a significant impact on the old-age dependency ratio, i.e. the number of people of working age for each person over retirement age.

Life expectancy in the developed world is now prolonged, even in old age , women aged 80 years can expect to live for a further 10 years.

However, rates of disability and chronic illness rise sharply with ageing and have a major impact on health.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

Biology of ageingAgeing can be defined as a progressive accumulation

through life of random molecular defects that build up

within tissues and cells. Eventually, despite multiple

repair and maintenance mechanisms, these result in agerelated functional impairment of tissues and organs.

Many genes probably contribute to ageing, with

those that determine durability and maintenance of

somatic cell lines particularly important. However,

genetic factors only account for around 25% of variance

in human lifespan; nutritional and environmental factors

determine the rest.

A major contribution to random molecular damage is

made by reactive oxygen species produced during the

metabolism of oxygen to produce cellular energy. These

cause oxidative damage at a number of sites:

• Nuclear chromosomal DNA, causing mutations and

deletions which ultimately lead to aberrant gene

function and potential for malignancy.

• Telomeres, which are the protective end regions of

chromosomes which shorten with each cell division because telomerase (which copies the end of the 3′ strand of linear DNA in germ cells) is absent in somatic cells.

When telomeres are sufficiently eroded, cells stop dividing. It has been suggested that telomeres represent a ‘biological clock’ which prevents uncontrolled cell division and cancer.

Telomeres are particularly shortened in patients with premature ageing due to Werner’s syndrome,

in which DNA is damaged due to lack of a helicase.

• Mitochondrial DNA and lipid peroxidation, resulting in

reduced cellular energy production and ultimately

cell death.

• Proteins – e.g. those increasing formation of

advanced glycosylation end-products from

spontaneous reactions between proteins and sugars.

These damage structure and function of the affected

protein, which becomes resistant to breakdown.

Chronic inflammation also plays an important role, in part by driving the production of reactive oxygen species.

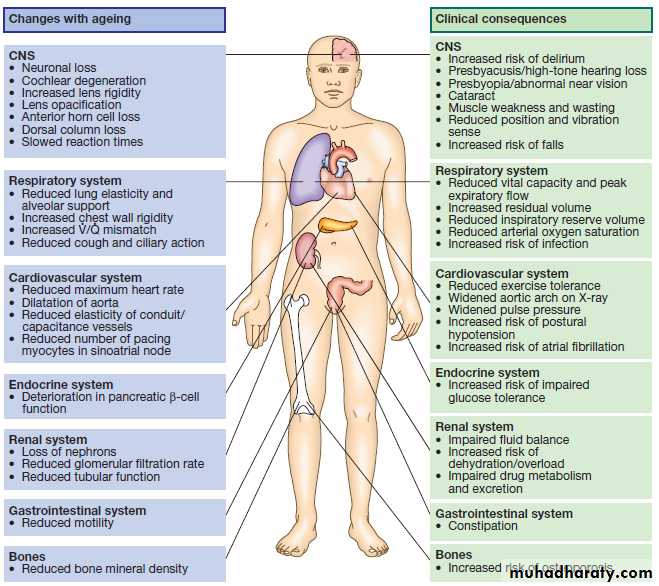

Physiological changes of ageing

The physiological features of normal ageing have been

identified by examining disease-free populations of

older people, to separate the effects of pathology from

those due to time alone. However, the fraction of older

people without disease ultimately declines to very low levels, so that ,the term ‘normal’ becomes debatable. There is a marked increase in inter-individual variation in function with ageing; many physiological processes deteriorate substantially when measured across populations, but some show little or no change. This heterogeneity is a hallmark of ageing, meaning that each person must be assessed individually and that one cannot unthinkingly apply the same management to all.

Although some genetic influences contribute to heterogeneity, environmental factors, such as poverty,

nutrition, exercise, cigarette smoking and alcohol

misuse, play a large part, and a healthy lifestyle should

be encouraged even when old age has been reached.

The effects of ageing are usually not enough to interfere

with organ function under normal conditions, but reserve capacity is significantly reduced. Some changes of ageing, such as depigmentation of the hair, are of no clinical significance.

Figure shows many factors that are clinically important.

Features and consequences of normal ageing

FrailtyFrailty is defined as the loss of an individual’s ability to

withstand minor stresses because the reserves in function

of several organ systems are so severely reduced

that even a trivial illness or adverse drug reaction may

result in organ failure and death. The same stresses

would cause little upset in a fit person of the same age.

It is important to understand the difference between

‘disability’, ‘comorbidity’ and ‘frailty’. Disability indicates

established loss of function (e.g. mobility), while frailty indicates increased vulnerability to loss of function. Disability may arise from a single pathological event (such as a stroke) in an otherwise healthy individual.

After recovery, function is largely stable and the patient may otherwise be in good health. When frailty and disability coexist, function deteriorates markedly even with minor illness, to the extent that the patient can no longer manage independently. Similarly, comorbidity (the number of diagnoses present) is not equivalent to frailty; it is quite possible to have several diagnoses without major impact on homeostatic reserve.

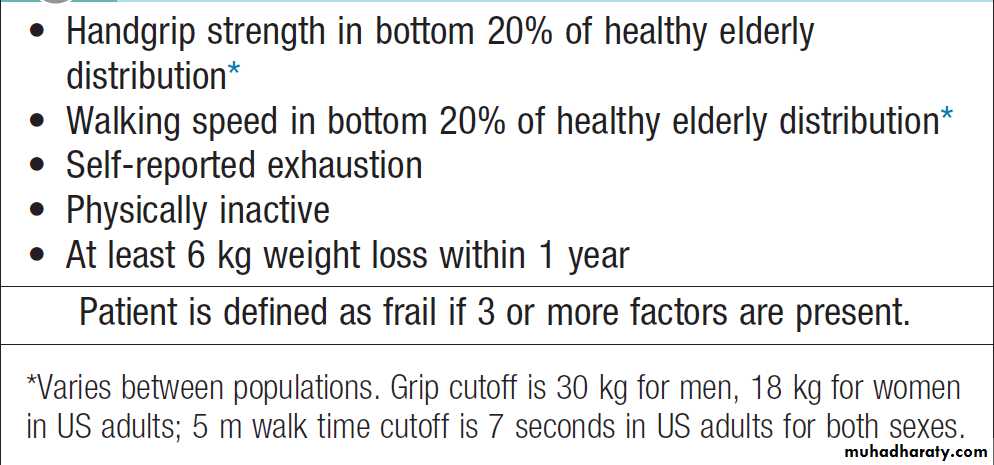

Unfortunately, the term ‘frail’ is often used rather

vaguely, sometimes to justify a lack of adequate investigation and intervention in older people. However, itcan be specifically identified by assessing function in a

number of domains. Two main approaches to evaluating

frailty exist: measurement of physiological function

across a number of domains (e.g. the Fried Frailty score,

Box), or a score based on the number of deficits or

problems – for example, the Rockwood score.

Frail older people particularly benefit from a clinical

approach that addresses both the precipitating acute

illness and their underlying loss of reserves.

It may be possible to prevent further loss of function through early intervention; for example, a frail woman with myocardial infarction will benefit from specific cardiac investigation and drug treatment, but may benefit even further from an exercise programme to improve musculoskeletal function, balance and aerobic capacity, with nutritional support to restore lost weight.

Establishing a patient’s level of frailty also helps inform decisions regarding further investigation and management, and the need for rehabilitation.

How to assess a Fried Frailty score

INVESTIGATIONS

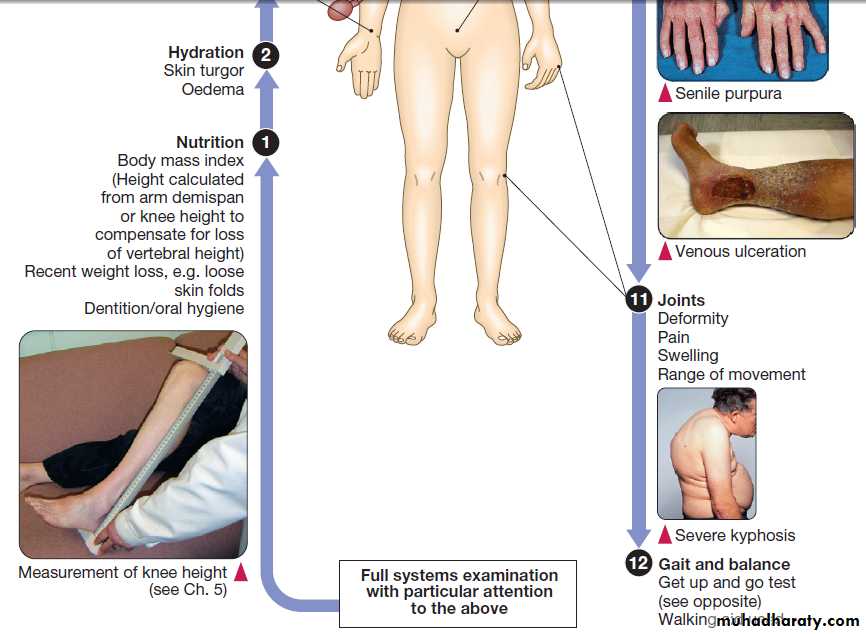

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

Although not strictly an investigation, one of the most

powerful tools in the management of older people is the

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, which identifies

all the relevant factors contributing to their presentation.

In frail patients with multiple pathology, it may

be necessary to perform the assessment in stages to

allow for their reduced stamina. The outcome should be

a management plan that not only addresses the acute

presenting problems, but also improves the patient’s

overall health and function.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment is performed

by a multidisciplinary team . Such an approachwas pioneered by Dr Marjory Warren at the West

Middlesex Hospital in London in the 1930s; her comprehensive assessment and rehabilitation of supposedly

incurable, long-term bedridden older people revolutionised

the approach of the medical profession to older,

frail people and laid the foundations for the modern

specialty of geriatric medicine.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

Decisions about investigation

Accurate diagnosis is important at all ages but frail olderpeople may not be able to tolerate lengthy or invasive

procedures, and diagnoses may be revealed for which

patients could not withstand intensive or aggressive

treatment. On the other hand, disability should never be

dismissed as due to age alone. For example, it would be

a mistake to supply a patient no longer able to climb

stairs with a stair lift, when simple tests would have

revealed osteoarthritis of a hip and vitamin D deficiency,

for which appropriate treatment would have restored

his or her strength.

So how do doctors decide when and how far to investigate?

The patient’s general health

Does this patient have the physical and mental capacityto tolerate the proposed investigation?

Does he have the aerobic capacity to undergo bronchoscopy?

Will confusion prevent her from remaining still in the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner?

The more comorbidities a patient has, the less likely he or she will be able to withstand an invasive intervention.

Will the investigation alter management?

Would the patient be fit for, or benefit from, the treatment

that would be indicated if investigation proved

positive? The presence of comorbidity is more important

than age itself in determining this. When a patient with severe heart failure and a previous disabling stroke

presents with a suspicious mass lesion on chest X-ray,

detailed investigation and staging may not be appropriate

if he is not fit for surgery, radical radiotherapy or

chemotherapy. On the other hand, if the same patient

presented with dysphagia, investigation of the cause

would be important, as he would be able to tolerate

endoscopic treatment (for example, to palliate an

obstructing oesophageal carcinoma).

The views of the patient and family

Older people may have strong views about the extent ofinvestigation and the treatment they wish to receive, and

these should be sought from the outset. If the patient

wishes, the views of relatives can be taken into account.

If the patient is not able to express a view or lacks

the capacity to make decisions because of cognitive

impairment or communication difficulties, then relatives’

input becomes particularly helpful. They may be

able to give information on views previously expressed

by the patient or on what the patient would have wanted

under the current circumstances. However, families should never be made to feel responsible for difficult decisions.

Advance directives

Or ‘living wills’ are statements made by adults at a time when they have the capacity to decide about the interventions they would refuse or accept in the future, should they no longer be able to make decisions or communicate them. An advance directive cannot authorise a doctor to do anything that is illegal and doctors are not bound to provide a specific treatment requested if, in their professional opinion, it is not clinically appropriate. However, any advance refusal of treatment, made when the patient was able to make decisions based on adequate information about their implications, is legally binding in the UK. It must be respected when it clearly applies to the patient’s present circumstances and when there is no reason to believe that the patient has changed his or her mind.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN GERIATRIC MEDICINE

Characteristics of presenting problems in old ageProblem-based practice is central to geriatric medicine.

Most problems are multifactorial and there is rarely a

single unifying diagnosis. All contributing factors have

to be taken into account and attention to detail is paramount.

Two patients who share the same presenting

problem may have completely disparate diagnoses.

A wide knowledge of adult medicine is required, as disease in any, and often many, of the organ systems has to be managed at the same time.

There are a number of features that are particular to older patients.

Late presentationMany people (of all ages) accept ill health as a consequence of ageing and may tolerate symptoms for lengthy periods before seeking medical advice. Comorbidities may also contribute to late presentation; in a patient whose mobility is limited by stroke, angina may only present when coronary artery disease is advanced, as the patient has been unable to exercise sufficiently to cause symptoms at an earlier stage.

Atypical presentation

Infection may present with delirium and without clinicalpointers to the organ system affected. Stroke may

present with falls rather than symptoms of focal weakness.

Myocardial infarction may present as weakness

and fatigue, without the chest pain or dyspnoea. The

reasons for these atypical presentations are not always

easy to establish. Perception of pain is altered in old age,

which may explain why myocardial infarction presents

in other ways. The pyretic response is blunted in old age

so that infection may not be obvious at first. Cognitive

impairment may limit the patient’s ability to give a

history of classical symptoms.

Acute illness and changes in function

Atypical presentations in frail elderly patients include

‘failure to cope’, ‘found on floor’, ‘confusion’ and ‘off

feet’, but these are not diagnoses. The possibility that an

acute illness has been the precipitant must always be

considered. To establish whether the patient’s current

status is a change from his or her usual level of function,

it helps to ask a relative or carer (by phone if necessary).

Investigations aimed at uncovering an acute illness will

not be fruitful in a patient whose function has been

deteriorating over several months, but are important if

function has suddenly changed.

Multiple pathology

Presentations in older patients have a more diversedifferential diagnosis because multiple pathology is

so common. There are frequently a number of causes

for any single problem, and adverse effects from

medication often contribute. A patient may fall because

of osteoarthritis of the knees, postural hypotension

due to diuretic therapy for hypertension, and poor

vision due to cataracts.

All these factors have to be addressed to prevent further falls, and this principle holds true for most of the common presenting problems in old age.

Approach to presenting problems in old age

For the sake of clarity, the common presenting problems

are described individually, but in real life, older

patients often present with several at the same time,

particularly confusion, incontinence and falls. These share some underlying causes and may precipitate each other.

The approach to most presenting problems in old age

can be summarised as follows:

• Obtain a collateral history. Find out the patient’s usual status (e.g. mobility, cognitive state) from a relative or carer. Call these people by phone if they are not present.

• Check all medication. Have there been any recent changes?

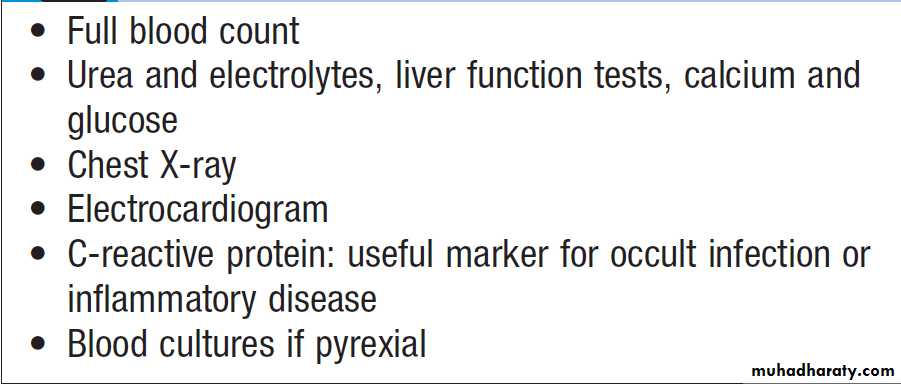

• Search for and treat any acute illness. See Box.

• Identify and reverse predisposing risk factors.These depend on the

presenting problem.

Screening investigations for acute illness

FallsAround 30% of those over 65 years of age fall each year. Although only 10–15% of falls result in serious injury,

cause of more than 90% of hip fractures, compounded by the rising prevalence of osteoporosis. Falls also lead to loss of confidence and fear, and are frequently the ‘final straw’ that makes an olddecide to move to institutional care.

Acute illness

Falls are one of the classical atypical presentations of

acute illness in frail people. The reduced reserves in

older people’s neurological function mean that they are

less able to maintain their balance when challenged by

an acute illness. Common underlying illnesses include infection, stroke, metabolic disturbance and heart failure.

Thorough examination and investigation are required (see Box). It is also important to establish whether any drug which precipitates falls, such as a psychotropic or hypotensive agent, has been started recently. Once the underlying acute illness has been treated, falls may stop.

Blackouts

A proportion of older people who ‘fall’ have, in fact, had

a syncopal episode. A collateral history from a witness

is of utmost importance in anyone falling over; people

who lose consciousness do not always remember having

done so. If loss of consciousness is suggested by the patient or witness, it is important to perform appropriate investigations

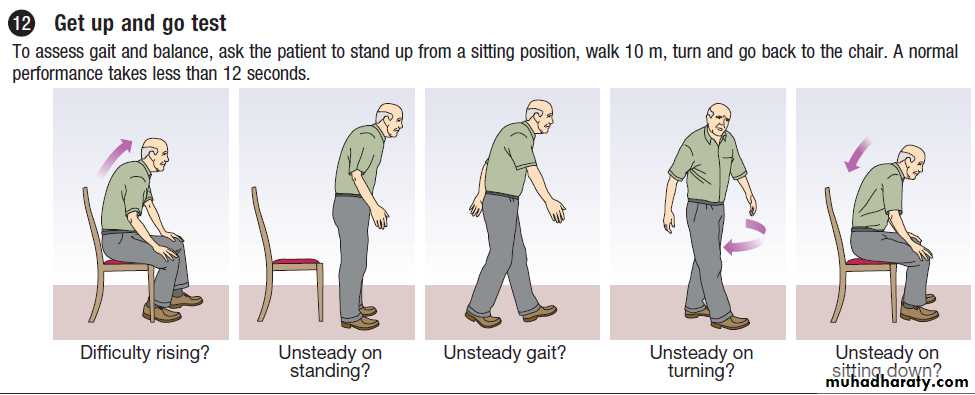

Mechanical and recurrent falls

Amongst patients who have tripped or are uncertainhow they fell, those who have fallen more than once

in the past year and those who are unsteady during a

‘get up and go’ test require further assessment.

Patients with recurrent falls are commonly frail, with

multiple medical problems and chronic disabilities.

Common pathologies identified include cerebrovascular

disease , Parkinson’s disease and osteoarthritis

of weight-bearing joints . Osteoporosis risk factors should also be sought and dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) bone density scanning considered in all older patients who have recurrent falls, particularly if they have already sustained a fracture.

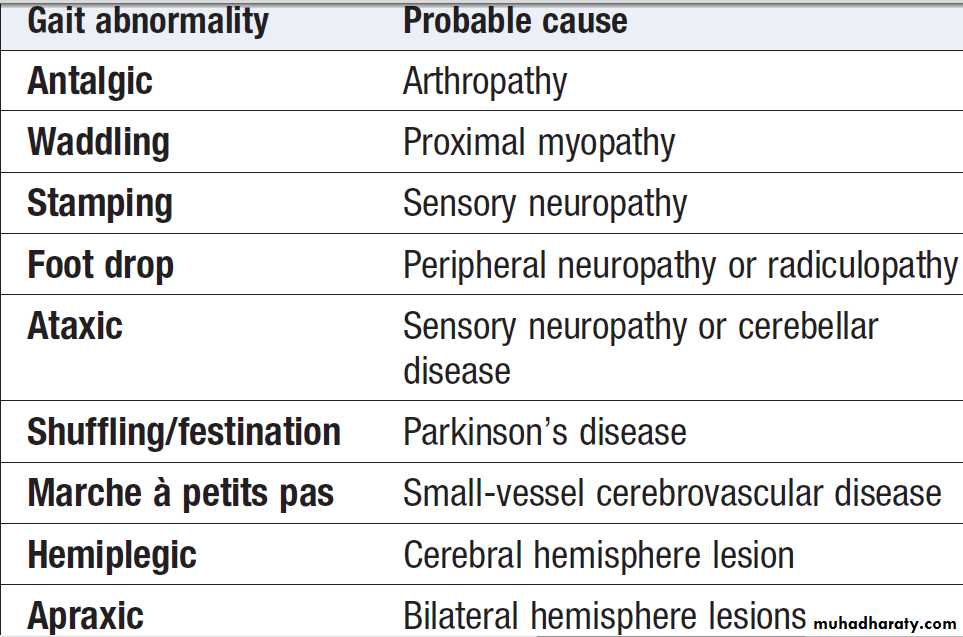

Abnormal gaits and probable causes

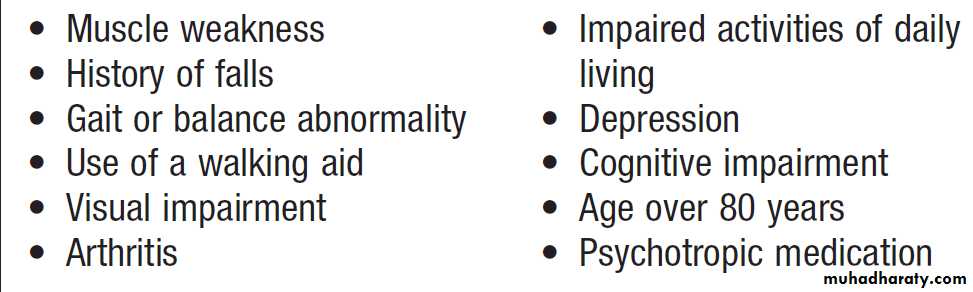

Risk factors for falls

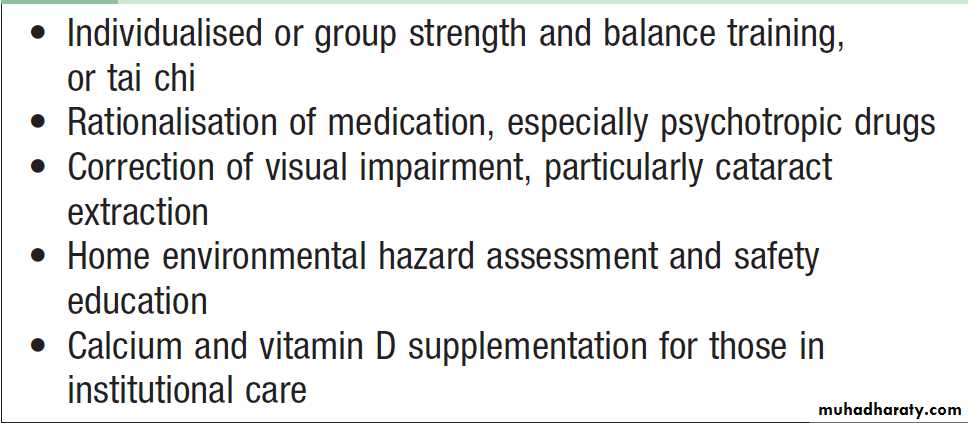

Prevention of falls and fracturesFalls can be prevented by multiple risk factor intervention

(Box). The most effective is balance and strength training by physiotherapists. An assessment of the patient’s home environment for hazards should be undertaken by an occupational therapist, who may also provide personal alarms so that patients can summon help, should they fall again. Rationalising psychotropic medication may help to reduce sedation, although many older patients are reluctant to stop hypnotics.

If postural hypotension is present (defined as a drop in blood pressure of > 20 mmHg systolic or > 10 mmHg diastolic pressure on standing from supine), reducing or stopping hypotensive drugs may be helpful.

Evidence supporting the efficacy of other interventions for postural hypotension is lacking, but drugs, fludrocortisone and midodrine, are sometimes used to improve dizziness on standing. Simple interventions, such as new glasses to correct visual acuity, and podiatry, can also have a significant impact on function in those who fall.

If osteoporosis is diagnosed, specific drug therapy

should be commenced . In patients in institutional

care, calcium and vitamin D3 administration has been shown to reduce both falls and fracture rates,

through effects on both bone mineral density and neuromuscular function. They are not effective in those with

osteoporosis living in the community, in whom bisphosphonates are first-line therapy.

Evidence-based interventions to prevent falls in older people

Dizziness

Very common, affecting at least 30% aged over 65 years. Dizziness can be disabling and is also a risk factor for falls.

common causes include:

• hypotension due to arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, gastrointestinal bleed or pulmonary embolism

• onset of posterior fossa stroke

• vestibular neuronitis.

Although older people more commonly present with recurrent dizzy spells and often find it difficult to describe the sensation they experience, the most effective way of establishing the cause(s) of the problem is nevertheless to determine which of the following is predominant :

• lightheadedness, suggestive of reduced cerebral perfusion

• vertigo, suggestive of labyrinthine or brainstem disease

• unsteadiness/poor balance (joint or neurological disease).

In lightheaded patients, structural cardiac disease

(such as aortic stenosis) and arrhythmia must be considered,but disorders of autonomic cardiovascular control,

such as vasovagal syndrome and postural hypotension,

are the most common causes in old age. Hypotensive

medication may exacerbate these.

Vertigo in older patients is most commonly due

to benign positional vertigo , but if other brainstem symptoms or signs are present, MRI of the brain is required to exclude a cerebello-pontine angle lesion.

Delirium

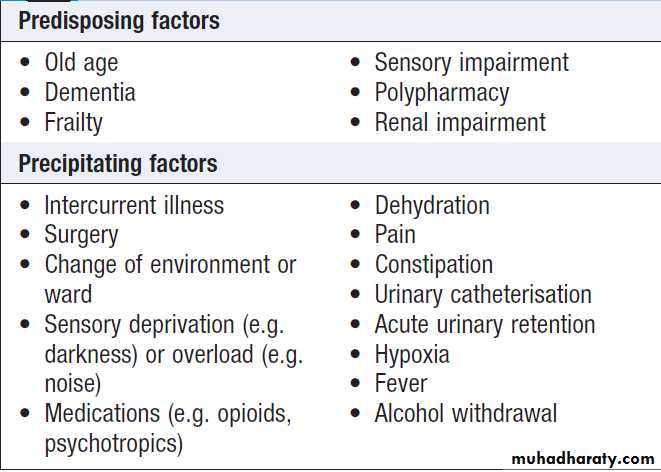

Delirium is a syndrome of transient, reversible cognitivedysfunction. It is very common, affecting up to

30% of older hospital inpatients, either at admission or

during their hospital stay. It is associated with high

rates of mortality, complication and institutionalisation,

and with longer lengths of stay. Risk factors are

shown in Box. Its pathophysiology is unclear; it

may in part be due to the effect of increased cortisol

release in acute illness, or it may reflect a sensitivity of

cholinergic neurotransmission to toxic insults. Older

terms for delirium, e.g. acute confusion or toxic confusional

state, lack diagnostic precision and should be avoided.

Risk factors for delirium

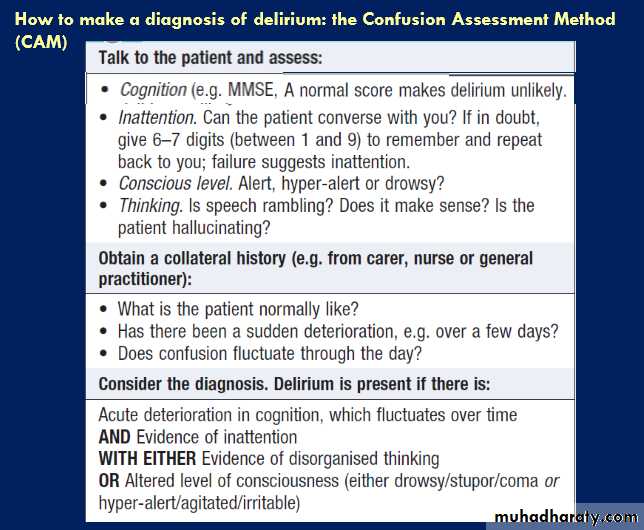

Clinical assessmentAssessment has two main goals: firstly, to establish the

diagnosis of delirium; and secondly, to identify all

of the reversible precipitating factors to allow optimal

treatment.

Delirium may be missed unless routine cognitive

testing with an Abbreviated Mental Test, CLOX test or

mini-mental state examination (MMSE) is performed.

Delirium often occurs in patients with dementia, and a history from a relative or carer about the onset and course of confusion is needed to distinguish acute from chronic features. The Confusion Assessment Method (Box) is a useful tool to diagnose delirium accurately and to differentiate the condition from dementia.

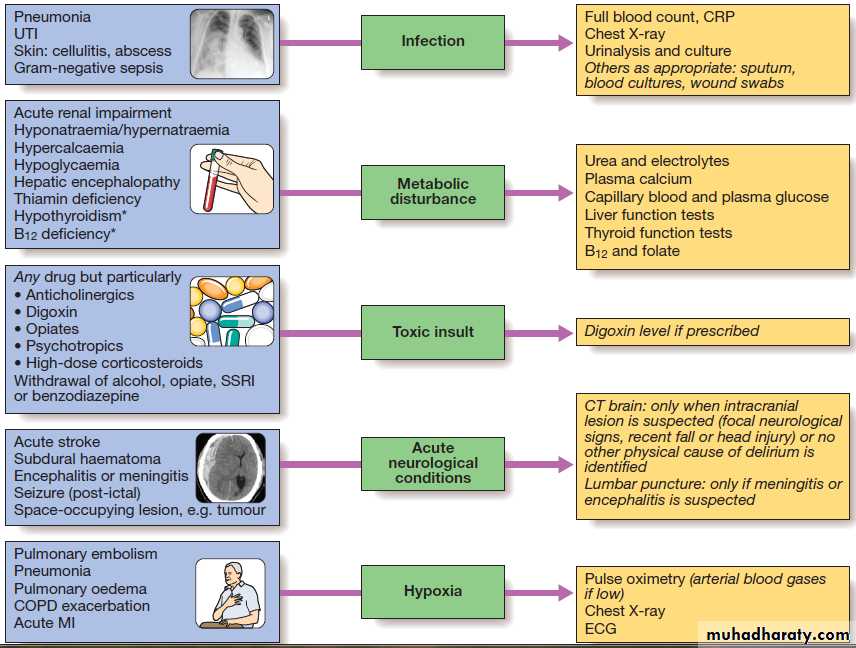

More than one of the precipitating causes of delirium

is often present. Symptoms suggestive of aphysical illness, such as an infection or stroke, should be

elicited. An accurate drug and alcohol history is required,

especially to ascertain whether any drugs have been

recently stopped or started. A full physical examination should be performed, noting in particular:

• pyrexia and any signs of infection in the chest, skin,

urine or abdomen

• oxygen saturation

• signs of alcohol withdrawal, such as tremor or sweating

• any neurological signs.

A range of investigations are needed to identify the

common causes

Fig. Common causes and investigation of delirium. All investigations are performed routinely, except those in italics. *Tend to present over weeks to months rather than hours to days. The chest X-ray shows consolidation in pneumonia.

The CT scan shows a cerebral haemorrhage. (COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP = C-reactlve protein; MI = myocardial infarction; SSRI = selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor; UTI = urinary tract infection)

Management

Specific treatment of all of the underlying causes mustbe commenced as quickly as possible. However, the

symptoms of delirium also require specific management.

To minimise ongoing confusion and disorientation, the environment should be kept well lit and not unduly noisy, with the patient’s spectacles and hearing aids in place. Good nursing is needed to preserve orientation, prevent pressure sores and falls, and maintain hydration, nutrition and continence. The use of sedatives should be kept to a minimum, as they can precipitate delirium. In any case, many confused patients are lethargic and apathetic rather than agitated. Sedation is very much a last resort, and is appropriate only if patients’ behaviour is endangering themselves or others.

Small doses of haloperidol (0.5 mg twice daily) are tried orally first, and the dose increased if the patient fails to respond. Sedation can be given intramuscularly only if absolutely necessary. In those with alcohol withdrawal or Lewy body dementia , a reducing course of a benzodiazepine should be prescribed.

In other cases, benzodiazepines should be avoided, as they may prolong delirium.

The resolution of delirium in old age may be slow

and incomplete. Many patients fail to recover to their

pre-morbid level of cognition. Delirium may be the first

presentation of an underlying dementia and is also a risk

factor for subsequent dementia.

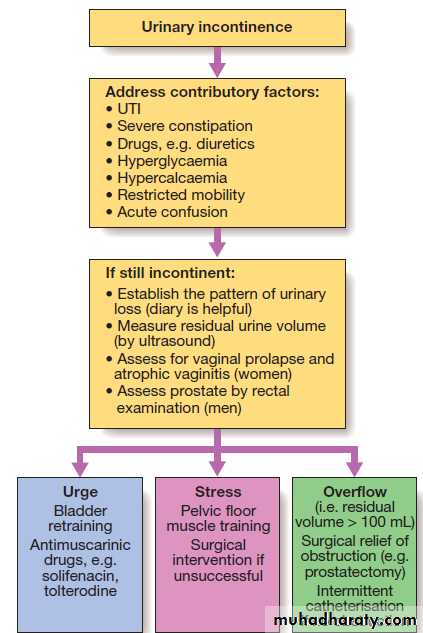

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence is defined as the involuntary loss

of urine and comes to medical attention when sufficiently

severe to cause a social or hygiene problem. It

occurs in all age groups but becomes more prevalent in

old age, affecting about 15% of women and 10% of men

aged over 65. It may lead to skin damage if severe and

can be socially restricting. While age-dependent changes

in the lower urinary tract predispose older people to

incontinence, it is not an inevitable consequence of ageing and requires investigation and appropriate treatment.

Urinary incontinence is frequently precipitated by

acute illness in old age and is commonly multifactorial.

Initial management is to identify and address contributory

factors. If incontinence fails to resolve, further diagnosis and management should be pursued.• Urge incontinence is usually due to detrusor over-activity and results in urgency and frequency.

• Stress incontinence is almost exclusive to women and is due to weakness of the pelvic floor muscles, which allows leakage of urine when intraabdominal pressure rises, e.g. on coughing. It may be compounded by atrophic vaginitis, associated with oestrogen deficiency in old age, which can be treated with oestrogen pessaries.

• Overflow incontinence ,commonly seen in elderly with prostatic enlargement, which obstructs bladder outflow.

In patients with severe stroke disease or dementia,

treatment may be ineffective, as frontal cortical inhibitorysignals to bladder emptying are lost. A timed/

prompted toileting programme may help. Other than in

overflow incontinence, urinary catheterisation should

never be viewed as first-line management, but may be

required as a final resort if the perineal skin is at risk of

breakdown or quality of life is affected.

Assessment and management of urinary incontinence

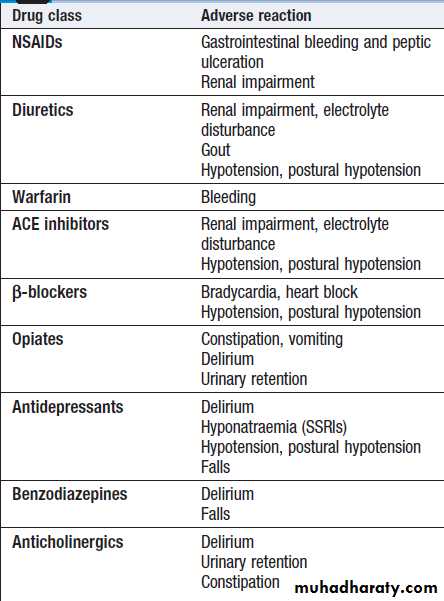

in old age.Adverse drug reactions

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and the effects of druginteractions are discussed on pages 24–28. They may

result in symptoms, abnormal physical signs and altered

laboratory test results . ADRs are the cause of around 5% of all hospital admissions but account for up to 20% of admissions in those aged over 65. This is partly

because older people receive many more prescribed

drugs than younger people. Polypharmacy has been

defined as the use of four or more drugs; this should be

avoided if possible, but is not always inappropriate

because many conditions, such as hypertension and heart failure, necessitate the use of several drugs, and older people may have several coexisting medical problems.

However, the more drugs that are taken, the greater the risk of an ADR. This risk is compounded by age-related changes in pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic factors and by impaired homeostatic mechanisms, such as baroreceptor responses, plasma volume and electrolyte control.

Older people are thus especially sensitive to drugs that can cause postural hypotension or volume depletion .

Nonadherence to drug therapy also rises with the number of drugs prescribed.

The clinical presentations of ADRs are diverse, so for

any presenting problem in old age the possibility that the

patient’s medication is a contributory factor should

always be considered. Failure to recognise this may lead

to the use of a further drug to treat the problem, making

matters worse, when the better course would be to stop

or reduce the dose of the offending drug or to find an

alternative. Regular review of medications is important in preventing ADRs. The patient or carer should be asked to bring all medication for review rather than the doctor relying on previous records. Those drugs that are no longer needed or are contraindicated can be discontinued.

Common adverse drug reactions in old age

Factors leading to polypharmacy in old age• Multiple pathology

• Poor patient education

• Lack of routine review of all medications

• Patient expectations of prescribing

• Over-use of drug interventions by doctors

• Attendance at multiple specialist clinics

• Poor communication between specialists

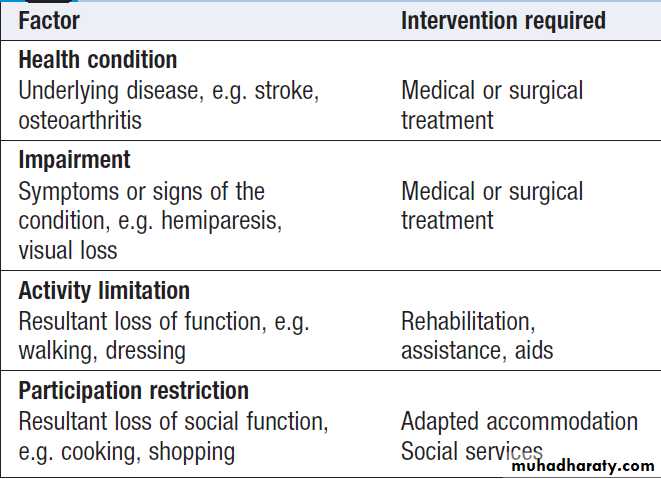

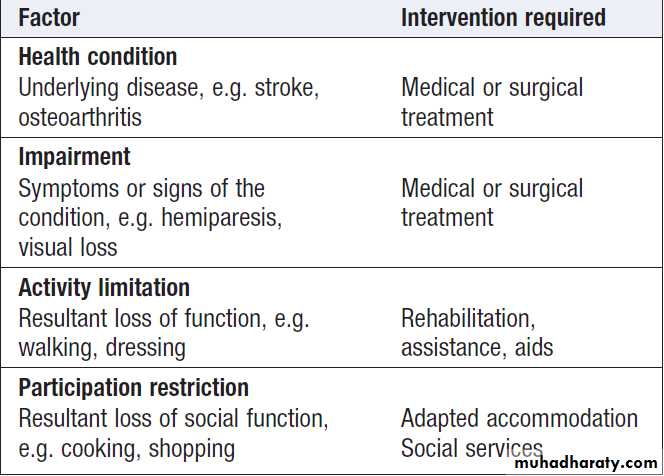

REHABILITATION

Rehabilitation aims to improve the ability of people of

all ages to perform day-to-day activities, and to restore

their physical, mental and social capabilities as far as

possible. Acute illness in old is often associated with loss of their usual ability to walk or care for themselves, and common disabling conditions such as stroke, fractured neck of femur, arthritis and cardiorespiratory disease become increasingly prevalent with advancing age. Disability is an interaction between factors intrinsic to the individual and the context in which they live. Doctors tend to focus on health conditions and impairments, but patients are more concerned with the effect on their activities and ability to participate in everyday life.

International classification of functioning and disability

The rehabilitation processRehabilitation is a problem-solving process focused

on improving the patient’s physical, psychological and

social function. It entails:

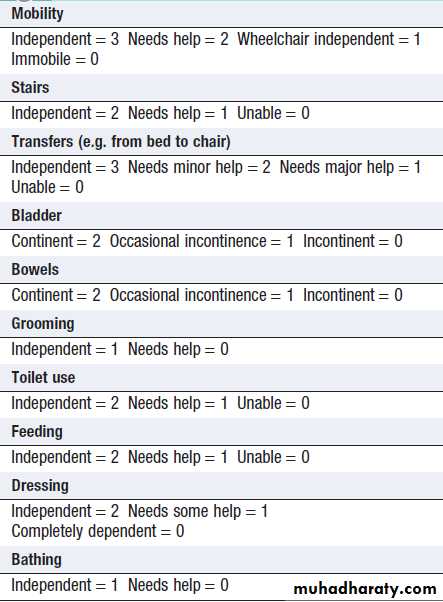

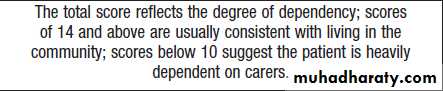

• Assessment. The nature and extent of the patient’s problems can be identified using the framework in Box . Specific assessment scales, such as the Elderly Mobility Scale or Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living , are useful to quantify components of disability, but additional assessment is needed to determine the underlying causes or the interventions required in individual patients.

• Goal-setting. Goals should be specific to the patient’s

problems, realistic, and agreed between the patient

and the rehabilitation team.

• Intervention. This includes the active treatments needed to achieve the established goals and to maintain the patient’s health and quality of life.Interventions include hands-on treatment by therapists using a functional, task-orientated approach to improve day-to-day activities, and also psychological support and education.

The emphasis on the type of intervention will be individualised, according to the patient’s disabilities, psychological status and progress.

The patient and carer(s) must be active participants.

• Re-assessment. There is ongoing re-evaluation of the

patient’s function and progress towards the goals

by the rehabilitation team, the patient and the carer.

Interventions may be modified as a result.

Multidisciplinary team working

The core rehabilitation team includes all members of

the multidisciplinary team . Others may be involved, e.g. audiometry to correct hearing impairment, podiatry for foot problems, and orthotics where a prosthesis or splinting is required. Good communication and mutual respect are essential. Regular team meetings allow sharing of assessments, agreement of rehabilitation goals and interventions, evaluation of progress and planning for the patient’s discharge home.

Rehabilitation is not when the doctor orders ‘physio’ or ‘a home visit’, and takes no further role.

Rehabilitation outcomes

There is evidence that rehabilitation improves functionaloutcomes in older people following acute illness,

stroke and hip fracture. It also reduces mortality after

stroke and hip fracture.

These benefits accrue from complex multi-component interventions, but occupational therapy to improve personal ADLs and individualized exercise interventions have now been shown to be effective in improving functional outcome in their own right.

International classification of functioning

and disabilityHow to assess rehabilitation needs using

the Modified Barthel Index

(20-point version)