The rectual tumors

Dr. Mohammed Abdzaid AgoolFIBMS, MRCS, FACS

BENIGN TUMOURS

The rectum, along with the sigmoid colon, is the most frequent site of polyps (and cancers) in the gastrointestinal tract.Adenomatous polyps of the colon and rectum have the potential to become malignant. The chance of developing invasive cancer is enhanced if the polyp is more than 1 cm in diameter.

Removal of all polyps is recommended to give complete histological examination and exclude (or confirm) carcinoma, and also to prevent local recurrence. This is best done using endoscopic hot biopsy or snare polypectomy techniques.

If one or more rectal polyps are discovered on sigmoidoscopic examination, a colonoscopy must be performed, as further polyps are frequently found in the colon and treatment may be influenced.

No rectal polyp should be removed until the possibility of a proximal carcinoma has been ruled out, otherwise local implantation of cancer cells may occur in the distally situated rectal wound.

Polyps in the rectum:

■ Are either single or multiple

■ Adenomas are the most frequent histological type

■ Villous adenomas may be extensive and undergo malignant change more commonly than tubular adenomas

■ All adenomas must be removed to avoid carcinomatous change

■ All patients must undergo colonoscopy to determine whether further polyps are present

■ Most polyps can be removed by endoscopic techniques, but sometimes major surgery is required.

Polyps may be pedunculated or sessile. Most pedunculated polyps are amenable to colonoscopic snare excision. Removal of sessile polyps is often more challenging

Polyps relevant to the rectum

Juvenile polyp:

This is a bright-red glistening pedunculated sphere (‘cherry tumour’), which is found in infants and children. Occasionally, it persists into adult life. It can cause bleeding, or pain if it prolapses during defaecation.

It often separates itself, but can be removed easily with forceps or a snare. A solitary juvenile polyp has virtually no tendency to malignant change, but should be treated if it is causing symptoms. It has a unique histological structure of large mucus-filled spaces covered by a smooth surface of thin rectal cuboidal epithelium.

The rare autosomal dominantly inherited syndrome juvenile polyposis does confer an increased risk of gastrointestinal cancers. It is characterised by multiple juvenile polyps and a positive family history

Hyperplastic polyps:

These are small, pinkish, sessile polyps, 2–4 mm in diameter and frequently multiple. They are harmless.Inflammatory pseudopolyps:

These are oedematous islands of mucosa. They are usually associated with colitis (in ulcerative colitis), but most inflammatory diseases (including tropical diseases) can cause them. They are more likely to cause radiological difficulty as the sigmoidoscopic appearances are usually associated with obvious signs of the inflammatory cause.

Villous adenomas

These have a characteristic frond-like appearance. They may be very large, and occasionally fill the entire rectum. These tumors have an enhanced tendency to become malignant – a change that can sometimes be detected by palpation with the finger; any hard area should be assumed to be malignant and should be biopsied.Rarely, the profuse mucous discharge from these tumors, which is rich in potassium, causes dangerous electrolyte and fluid losses.

Provided cancerous change has been excluded, these tumors can be removed by submucosal resection endoscopically, surgically per anum or by sleeve resection from above. Only very occasionally is rectal excision required.

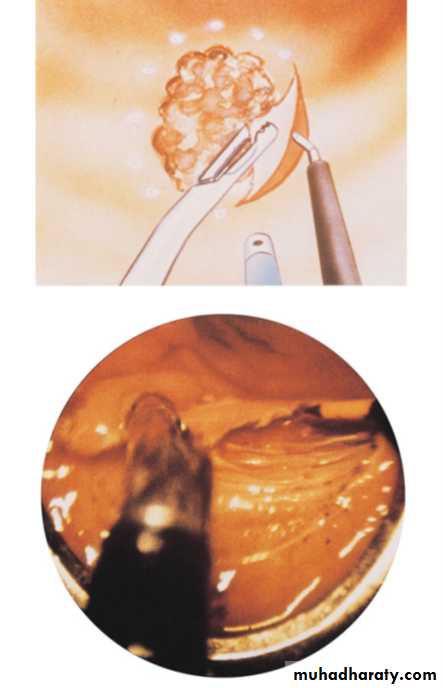

A recent technique known as transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) has been developed , which has improved the endoanal approach for the local removal of villous adenomas. The method requires the insertion of a large operating sigmoidoscope. The rectum is distended by carbon dioxide insufflation, the operative field is magnified by a camera inserted via the sigmoidoscope, and the image is displayed on a monitor . The lesion is excised using specially designed instruments.

The technique is highly specialised and takes a considerable amount of time to master.

Familial adenomatous polyposis

This autosomal dominantly inherited condition is characterised by the development of multiple rectal and colonic polyps around puberty. A colonoscopy and biopsy will confirm the diagnosis.Recently, the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene responsible for the disease has been isolated on chromosome 5 (Bodmer), and its sequence has been determined. This discovery makes the screening of affected families far more straightforward.

As this condition is pre-malignant,

1- a total colectomy must be performed; often, the rectum can be preserved, but regular flexible endoscopy and removal of polyps before they develop carcinoma are required.

2- or The operation of restorative proctocolectomy with pouch–anus anastomosis is an alternative if proctectomy is required: the rectum is replaced by a ‘pouch’ of folded ileum.

3- A pan-proctocolectomy with permanent ileostomy is necessary in some instances, especially when patient follow-up may be impractical.

Other rare rectal tumors:

Benign lymphoma.Endometrioma.

Haemangioma.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour.

CARCINOMAS:

Overall, colorectal cancer is the second most common malignancy in western countries, with approximately 18 000 patients dying per annum in the UK. The rectum is the most frequent site involved.

Origin

It is now accepted that colorectal cancer arises from adenomas in a stepwise progression in which increasing dysplasia in the adenoma is due to an accumulation of genetic abnormalities (the adenoma–carcinoma sequence).In approximately 5% of cases, there is more than one carcinoma present. Usually, these carcinomas present as an ulcer, but polypoid and infiltrating types are also common.

Types of carcinoma spread

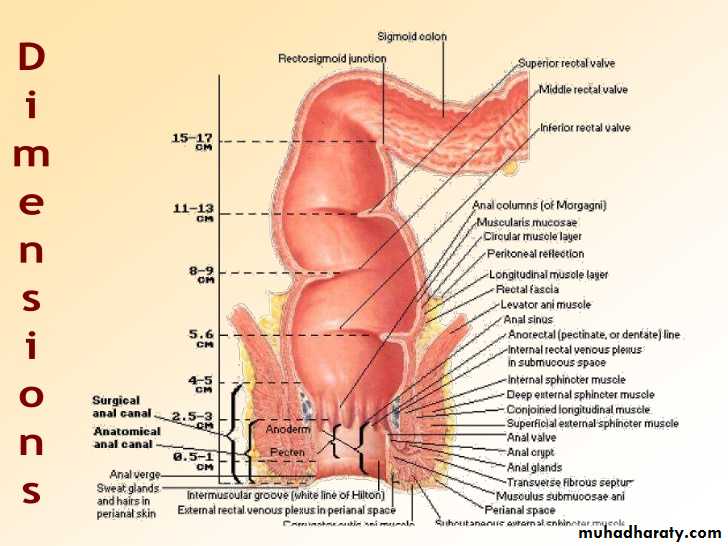

Local spreadLocal spread occurs circumferentially rather than in a longitudinal direction. It is thought that a period of 6 months is required for involvement of a quarter of the circumference, and 18 months to 2 years for complete encirclement.

If penetration occurs anteriorly, the prostate, seminal vesicles or bladder become involved in the male; in the female, the vagina or the uterus is invaded. In either sex, if the penetration is lateral, a ureter may become involved, while posterior penetration may reach the sacrum and the sacral plexus. Downward spread for more than a few centimetres is rare.

Lymphatic spread

Lymphatic spread from a carcinoma of the rectum above the peritoneal reflection occurs almost exclusively in an upward direction;below that level, the lymphatic spread is still upwards, but when the neoplasm lies within the field of the middle rectal artery, primary lateral spread along the lymphatics that accompany it is not infrequent.

Downward spread is exceptional, with drainage along the subcutaneous lymphatics to the groins being confined, for practical purposes, to the lymph nodes draining the perianal rosette and the epithelium lining the distal 1–2 cm of the anal canal.

Metastasis at a higher level than the main trunk of the superior rectal artery occurs only late in the disease.

Venous spread

The principal sites for blood-borne metastases are liver (34%), lungs (22%) and adrenals (11%). The remaining 33% are divided among the many other locations where secondary carcinomatous deposits tend to lodge, including the brain.Peritoneal dissemination

This may follow penetration of the peritoneal coat by a high-lying rectal carcinoma.

Stages of progression

Dukes classified carcinoma of the rectum into three stages:A The growth is limited to the rectal wall (15%): prognosis excellent.

B The growth is extended to the extrarectal tissues, but no metastasis

to the regional lymph nodes (35%): prognosis reasonable.

C The growth There are secondary deposits in the regional lymph nodes (50%). These are subdivided into C1, in which the local pararectal lymph nodes alone are involved, and C2, in which the nodes accompanying the supplying blood vessels are implicated up to the point of division.

A stage D is often included, which was not described by Dukes. This stage signifies the presence of widespread metastases, usually hepatic.

The tumour–node–metastasis (TNM) classification is now recognised internationally as the optimum classification for staging.

T represents the extent of local spread and there are four grades:

• T1 tumour invasion through the muscularis mucosae, but not into the muscularis propria;

• T2 tumour invasion into but not through the muscularis propria;

• T3 tumour invasion through the muscularis propria, but not through the serosa (on surfaces covered by peritoneum) or mesorectal fascia;

• T4 tumour invasion through the serosa or Mesorectal fascia.

N describes nodal involvement:

• N0 no lymph node involvement;

• N1 1–3 involved lymph nodes;

• N2 4 or more involved lymph nodes.

M indicates the presence of distant metastases:

• M0 no distant metastases;

• M1 distant metastases.

The prefix ‘p’ indicates that the staging is based on histopathological analysis, and ‘y’ that it is the stage after neoadjuvant treatment, which may have resulted in downstaging.

Histological grading

In the great majority of cases, carcinoma of the rectum is a columnar-celled adenocarcinoma. The more nearly the tumour cells approach normal shape and arrangement, the less malignant the tumour is. Conversely, the greater the percentage of cells of an undifferentiated type, the more malignant the tumour is:• Low grade = well-differentiated 11% prognosis good;

• Average grade 64% prognosis fair;

• High grade = anaplastic tumours 25% prognosis poor.

Vascular and perineural invasion are poor prognostic features, as is the presence of an infiltrating (rather than pushing) margin. In a small number of cases, the tumour is a primary mucoid carcinoma.

The mucus lies within the cells, displacing the nucleus to the periphery, like the seal of a signet ring. Primary mucoid carcinoma gives rise to a rapidly growing bulky growth that metastasizes very early and the prognosis of which is very poor

Clinical features

Carcinoma of the rectum can occur early in life, but the age of presentation is usually above 55 years, when the incidence rises rapidly.Often, the early symptoms are so insignificant that the patient does not seek advice for 6 months or more, and the diagnosis is often delayed in younger patients as these symptoms are attributed to benign causes.

Initial rectal examination and a low threshold for investigating persistent symptoms are essential to prevent this.

Early symptoms of rectal cancer:

■ Bleeding per rectum

■ Tenesmus(Alteration in bowel habit)

■ Early morning diarrhoea

Pain

Pain is a late symptom, but pain of a colicky character may accompany advanced tumours of the rectosigmoid, and is caused by some degree of intestinal obstruction.

When a deep carcinomatous ulcer of the rectum erodes the prostate or bladder, there may be severe pain. Pain in the back, or sciatica, occurs when the cancer invades the sacral plexus.

Weight loss is suggestive of hepatic metastases.

InvestigationAbdominal examination.

Rectal examination.

Proctosigmoidoscopy

Colonoscopy synchronous tumour, be it an adenoma or a carcinoma

For preoperative staging and preparations:

a- CXY or chest CT Scan

b- CT Scan and Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning can be helpful in identifying metastases if imaging is otherwise equivocal.

c- locoregional extension by pelvic MRI +\ - endoanal ultrasounograghy.

Biopsy

Diagnosis and assessment of rectal cancer

All patients with suspected rectal cancer should undergo:■ Digital rectal examination

■ Sigmoidoscopy and biopsy

■ Colonoscopy if possible (or CT colonography or barium enema).

All patients with proven rectal cancer require staging by:

■ Imaging of the liver and chest, preferably by CT

■ Local pelvic imaging by magnetic resonance imaging and/or endoluminal ultrasound.

Treatment

Some form of excision of the rectum is essentialHowever, before surgery is embarked upon, it is necessary to assess:

• the fitness of the patient for operation;

• the extent of spread of the tumour.

Principles of surgical treatment:

Radical excision of the rectum, together with the mesorectum and associated lymph nodes, should be the aim.

Even in the presence of widespread metastases, a rectal excision should be considered, as this is often the best means of palliation.

The presence of liver metastases does not necessarily rule out the feasibility of a radical excision.

When a tumour appears to be locally advanced (i.e. invading a neighbouring structure or threatening to breach the circumferential resection margin), the administration of a course of preoperative chemoradiotherapy may reduce its size and make curative surgery possible.

Recent evidence suggests that the administration of preoperative ‘short-course’ Neoadjuvant radiotherapy in resectable rectal cancer cases significantly reduces the incidence of local recurrence.

For patients who are unfit for radical surgery or who have widespread metastases, a local procedure such as transanal excision, laser destruction or interstitial radiation should be considered.

When a rectal excision is possible, whenever feasible, the aim should be to restore gastrointestinal continuity and continence by preserving the anal sphincter. A sphincter-saving operation (anterior resection) is usually possible for tumours whose lower margin is two or more centimetres above the anal canal.

removal of the rectum with a permanent colostomy (abdominoperineal excision) was often required for tumours of the lower third of the rectum when the distal margin of clearance of 2 cm can not be secured.

Rectosigmoid tumours and those in the upper third of the rectum are removed by (‘high anterior resection’), in which the rectum and mesorectum are taken to a margin 5 cm distal to the tumour, and a colorectal anastomosis is performed.

Preoperative preparation

■ Mechanical bowel preparation■ Counselling and siting of stomas

■ Correction of anaemia and electrolyte disturbance

■ Cross-matching of blood

■ Prophylactic antibiotics

■ Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis

■ Insertion of urethral catheter

Surgery for rectal cancer

■ Surgery is the mainstay of curative therapy■ The primary resection consists of rectal excision with TME

■ Most cases can be treated by anterior resection with the colorectal anastomosis being achieved with a circular stapling gun

■ A smaller group of low, extensive tumours require an abdominoperineal excision with a permanent colostomy

■ Preoperative radiotherapy can reduce local recurrence

■ Adjuvant chemotherapy can improve survival in node positive disease

■ Liver resection in carefully selected patients offers the best chance of cure for single or well-localised liver metastases