Hussien Mohammed Jumaah

CABMLecturer in internal medicine

Mosul College of Medicine

2016

learning-topics

Alimentary tract and pancreatic diseaseGastric secretion

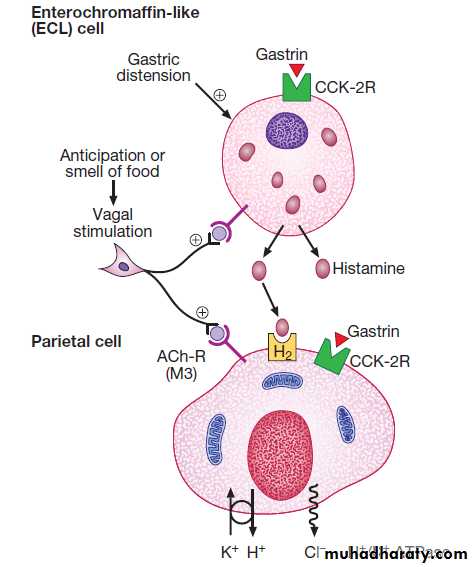

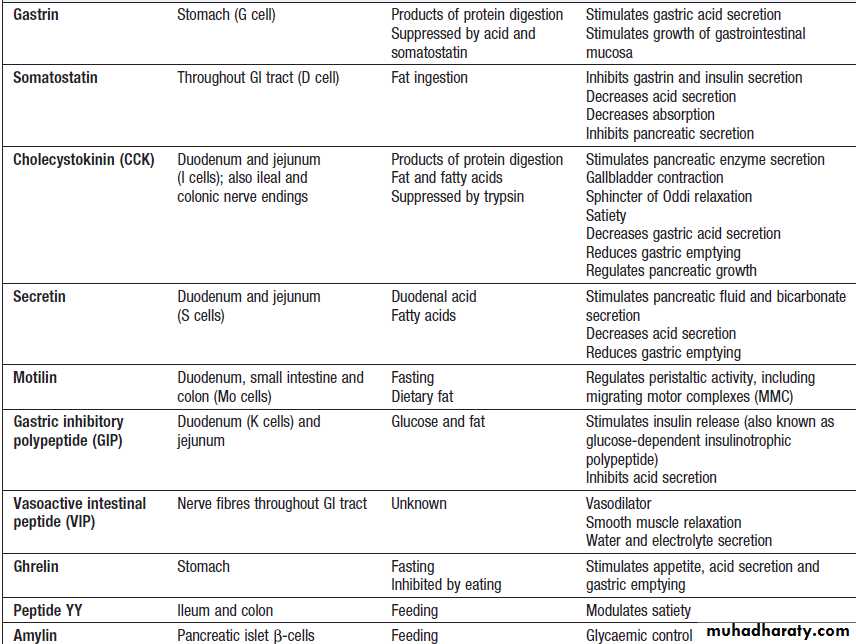

Gastrin secreted by G cells in the antrum (stimulates acid secretion and mucosal growth. Histamine and acetylcholine are the key stimulants of acid secretion) in response to food (protein) binds to cholecystokinin receptors (CCK-2R) on the surface of enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells, which in turn release histamine. The histamine binds to H2 receptors on parietal cells and this leads to secretion of hydrogen ions, in exchange for potassium ions at the apical membrane of parietal cells. Hydrogen and chloride ions are secreted from parietal cells into the lumen of the stomach by a H-K ATPase (proton pump) . Parietal cells also express CCK-2R and it is thought that activation of these receptors by gastrin is involved in regulatory proliferation of parietal cells.Cholinergic (vagal) activity and gastric distension also stimulate acid secretion ,whilst somatostatin is secreted from D cells throughout the stomach, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) may inhibit it. The hydrochloric acid sterilises the upper GIT and converts pepsinogen (secreted by chief cells) to pepsin.

The parietal cells produce the glycoprotein intrinsic factor, in parallel with acid, necessary for B12 absorption.

Ghrelin, secreted from oxyntic glands, stimulates acid secretion ,appetite and gastric emptying.

Protective factors: Bicarbonate ions, stimulated by prostaglandins, mucins and trefoil factor family (TFF) peptides protect the gastroduodenal mucosa from the ulcerative properties of acid and pepsin.

Control of acid secretion. Gastrin released from antral G cells in response to food (protein) binds to cholecystokinin receptors (CCK-2R) on the surface of enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells, which in turn release histamine. The histamine binds to H2 receptors on parietal cells and this leads to secretion of hydrogen ions, in exchange for potassium ions at the apical membrane. Parietal cells also express CCK-2R and it is thought that activation of these receptors by gastrin is involved in regulatory proliferation of parietal cells. Cholinergic (vagal) activity and gastric distension also stimulate acid secretion; somatostatin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) may inhibit it.

(ACh-R = acetylcholine receptor; ATPase = adenosine triphosphatase)

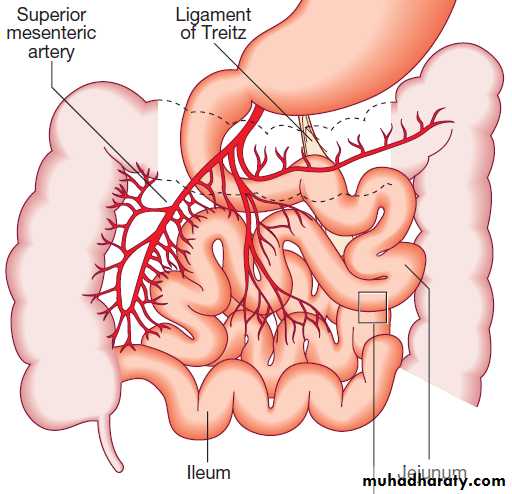

Small intestine

The small bowel extends from the ligament of Treitz tothe ileocaecal valve . During fasting, a wave of peristaltic activity passes down the small bowel every

1–2 hours. Entry of food into the gastrointestinal tract

stimulates small bowel peristaltic activity.

Functions of the small intestine are:

• digestion (mechanical, enzymatic and peristaltic)• absorption – the products of digestion, water,

electrolytes and vitamins

• protection against ingested toxins

• immune regulation.

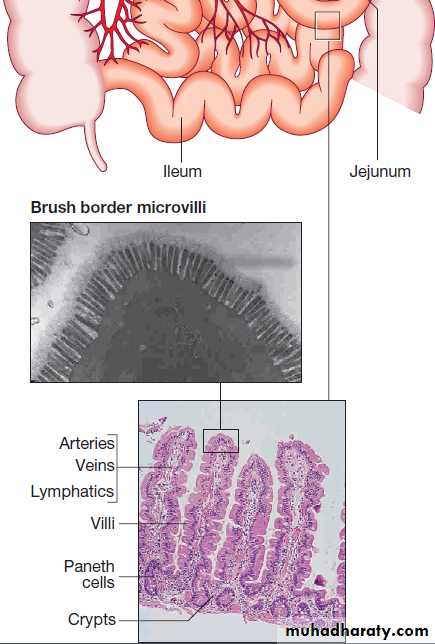

Small intestine: Epithelial cells are formed in crypts and differentiate as they migrate to the tip of the villi to form enterocytes (absorptive cells) and goblet cells.

Digestion and absorption

FatDietary lipids comprise long-chain triglycerides, cholesterol esters and lecithin. Lipids are insoluble in water and undergo lipolysis and incorporation into mixed micelles before they can be absorbed into enterocytes along with the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, K and E. The lipids are processed within enterocytes and pass via lymphatics into the systemic circulation.

Carbohydrates

Starch is hydrolysed by salivary and pancreatic amylases to alpha-limit dextrins containing 4–8 glucose molecules; to the disaccharide, maltose; and to the trisaccharide, maltotriose.Disaccharides are digested by enzymes fixed to the

microvillous membrane to form the monosaccharides,

glucose, galactose and fructose.

Glucose and galactose enter the cell by an energy-requiring process involving a carrier protein, and fructose enters by simple diffusion.

Protein

The steps involved in protein digestion are shown in Figure. Intragastric digestion by pepsin is quantitatively modest but important because the resulting polypeptides and amino acids stimulate CCK release from the mucosa of the proximal jejunum, which in turn stimulates release of pancreatic proteases, including trypsinogen, chymotrypsinogen, pro-elastases and procarboxypeptidases, from the pancreas.On exposure to brush border enterokinase, inert trypsinogen is converted to the active proteolytic enzyme trypsin, which activates the other pancreatic proenzymes.

Trypsin

digests proteins to produce oligopeptides, peptides and amino acids.Oligopeptides are further hydrolysed by

brush border enzymes to yield dipeptides, tripeptides and amino acids. These small peptides and the amino acids are actively transported into the enterocytes, where intracellular peptidases further digest peptides to amino acids. Amino acids are then actively transported across the basal cell membrane of the enterocyte into the portal circulation and the liver.

Water and electrolytes

Absorption and secretion of electrolytes and water occur throughout the intestine and are transported by

two pathways:

• the paracellular route, in which passive flow through

tight junctions between cells is a consequence of

osmotic, electrical or hydrostatic gradients

• the transcellular route across apical and basolateral

membranes by energy-requiring specific active

transport carriers (pumps).

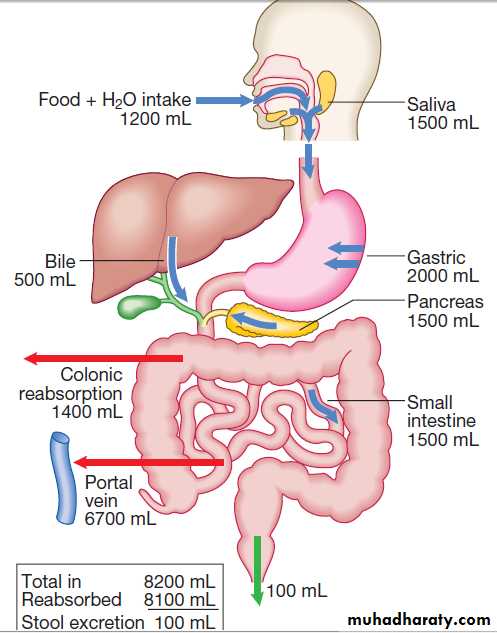

In healthy individuals, fluid balance is tightly controlled, such that only 100 mL of the 8 litres of fluid entering the GIT daily is excreted in stools .

Vitamins and trace elements

Water-soluble vitamins are absorbed throughout the intestine.

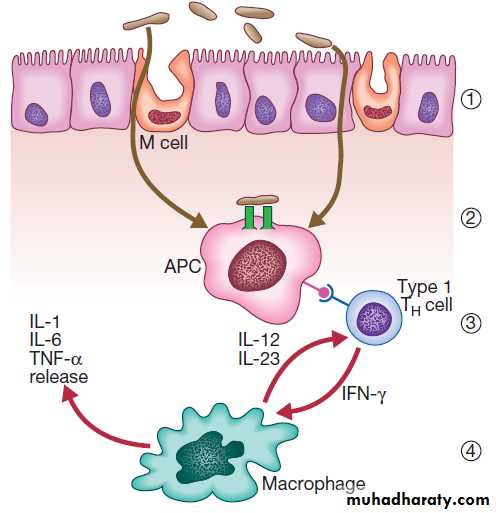

Intestinal defence mechanisms

Protective function of the small intestinePhysical defence mechanisms

There are several levels of defence in the small bowel (Fig).

Firstly, the gut lumen contains host bacteria, mucins and secreted antibacterial products, including defensins and immunoglobulins which help combat pathogenic infections.

Secondly, epithelial cells have relatively impermeable brush border membranes, and passage between cells is prevented by tight and adherens junctions.

These cells can react to foreign peptides (‘innate immunity’) using pattern recognition receptors found on cell surfaces (Toll receptors) or intracellularly.

Lastly, in the subepithelial layer, immune responses occur under control of the adaptive immune system in response to pathogenic compounds.

Immunological defence mechanisms

GI mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue constitutes 25% of the total lymphatic tissue of the body and is at the heart of adaptive immunity. Within Peyer’s patches, B lymphocytes differentiate to plasma cells following exposure to antigens, and these migrate to mesenteric lymph nodes, to enter the blood stream via the thoracic duct. The plasma cells return to the lamina propria of the gut through the circulation and release immunoglobulin A (IgA), which is transported into the lumen of the intestine. Intestinal T lymphocytes help localise plasma cells to the site of antigen exposure, producing inflammatory mediators. Macrophages phagocytose foreign materials and secrete cytokines, which mediate inflammation.

Pancreas

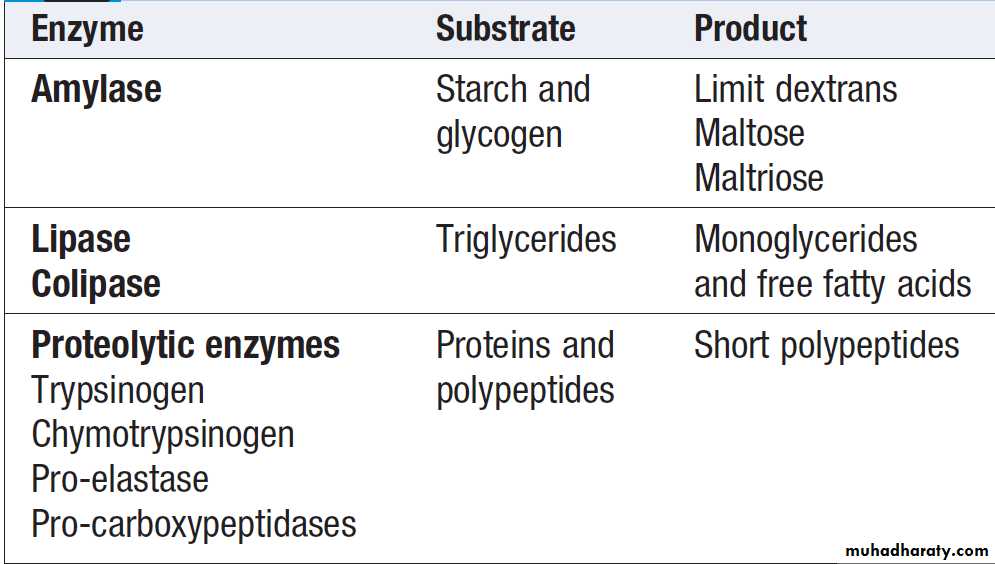

The exocrine pancreas is necessary for the digestion of fat, protein and carbohydrate. Proenzymes are secreted from pancreatic acinar cells in response to circulating GI hormones and are activated by trypsin. Bicarbonate-rich fluid is secreted from ductular cells to produce an optimum alkaline pH for enzyme activity.Pancreatic enzymes

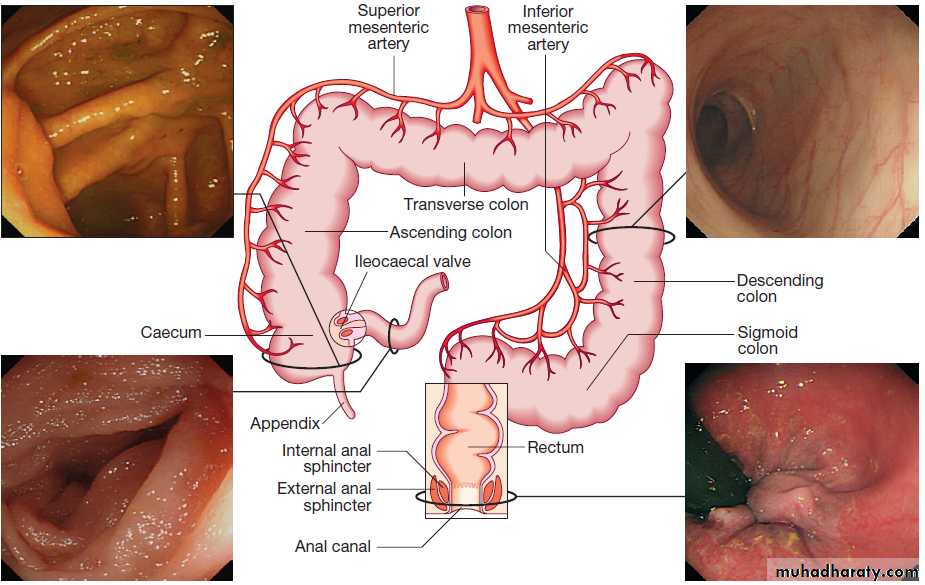

ColonAbsorbs water and electrolytes. Acts as a storage organ. Two types of contraction occur. The first is segmentation (ring contraction), which leads to mixing but not propulsion; this promotes absorption of water and electrolytes. Propulsive (peristaltic contraction) waves occur several times a day and propel faeces to the rectum. All activity is stimulated after meals, in response to release of motilin and CCK. Faecal continence depends upon maintenance of the anorectal angle and tonic contraction of the external anal sphincters.

On defecation, there is relaxation of the anorectal muscles, increased intra-abdominal pressure , contraction of abdominal muscles, and relaxation of the anal sphincters.

Control of gastrointestinal function

Secretion, absorption, motor activity, growth and differentiation of the gut are all modulated by a combination of neuronal and hormonal factors. The CNS, the autonomic system (ANS) and the enteric nervous system (ENS) interact to regulate gut function. The ANS comprises:• parasympathetic pathways (vagal and sacral efferent), which are cholinergic, and increase smooth muscle tone and promote sphincter relaxation

• sympathetic pathways, which release noradrenaline

(norepinephrine), reduce smooth muscle tone and

stimulate sphincter contraction.

The parasympathetic system generally stimulates motility and secretion, while the sympathetic system generally acts in an inhibitory manner.

The normal colon, rectum and anal canal.

Gut hormones and peptides

INVESTIGATION OF GASTROINTESTINAL DISEASE

ImagingPlain X-rays

Of the abdomen are useful in the diagnosis of intestinal obstruction or paralytic ileus, where dilated loops of bowel and (in the erect position) fluid levels. Calcified lymph nodes, gallstones and renal stones can also be detected. Chest X- ray (performed with the patient in erect position) is useful in the diagnosis of suspected perforation, as it shows subdiaphragmatic free air.

Contrast studies

X-rays with contrast medium are usually performed to assess not only anatomical abnormalities but also motility.

Water-soluble contrast is used to opacify bowel prior to abdominal CT and in cases of suspected perforation. The double contrast technique improves mucosal visualisation by using gas to distend the barium-coated intestinal surface. Contrast studies are useful for detecting filling defects, such as tumours, strictures, ulcers and motility disorders, but are inferior to endoscopic procedures and more sophisticated cross-sectional imaging techniques, such as CT and MRI.

Ultrasound, CT and MRI

US, CT and MRI are key tests in the evaluation of intra-abdominal disease. They are noninvasive and offer detailed images of the abdominal contents.

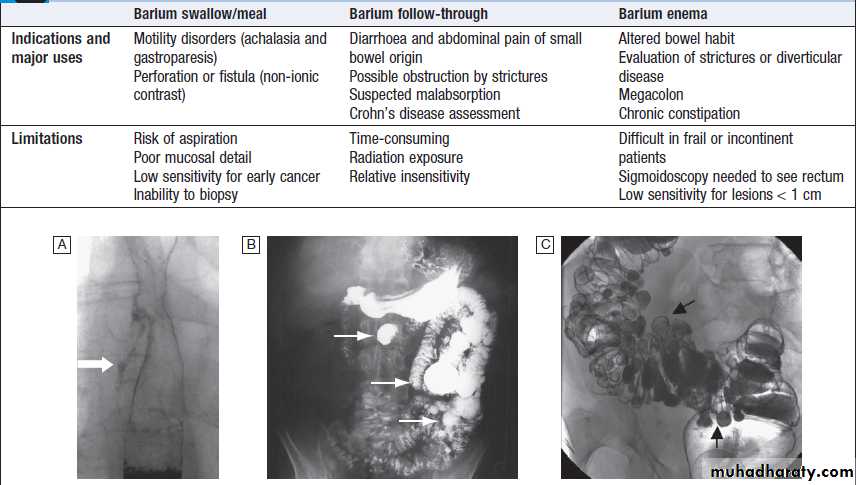

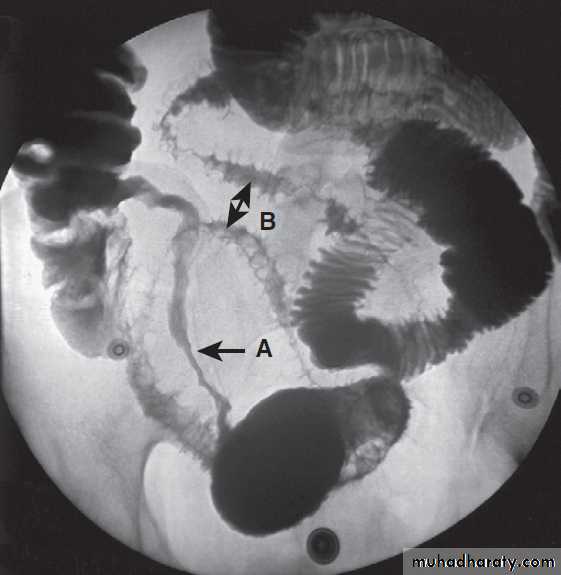

Contrast radiology in the investigation of gastrointestinal disease

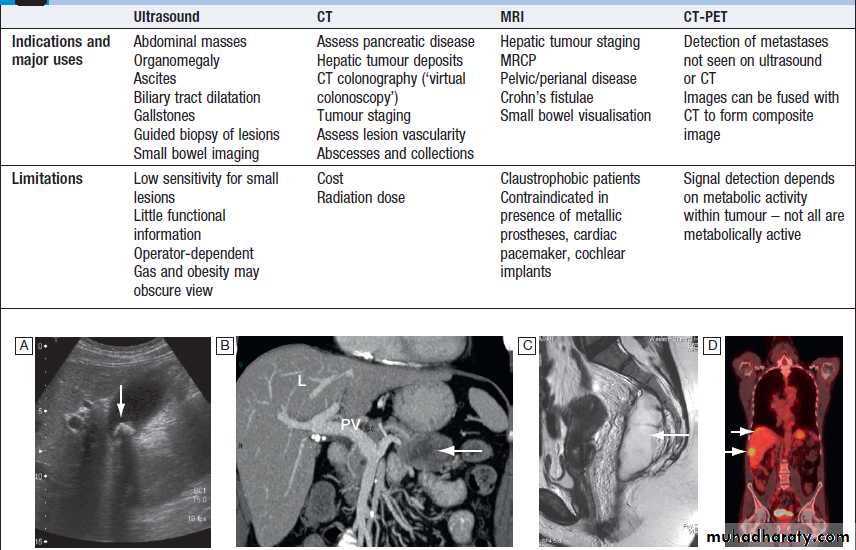

A Non-ionic contrast swallow shows leakage of contrast (arrow) into the mediastinum following stricture dilatation. B Barium follow-through. There are multiple diverticula (arrows) in this patient with jejunal diverticulosis. C Barium enema showing severe diverticular disease. There is tortuosity and narrowing of the sigmoid colon with multiple diverticula (arrows).Imaging in gastroenterology :Examples of ultrasound, CT and MRI. A Ultrasound showing large gallstone (arrow) with acoustic shadowing. B Multidetector coronal CT showing large solid and cystic malignant tumour in the pancreatic tail (arrow). (PV = portal vein; L = liver) C Pelvic MRI showing large pelvic abscess (arrow) posterior to the rectum in a patient with Crohn’s disease. D Fused CT-PET image showing two liver metastases (arrows).

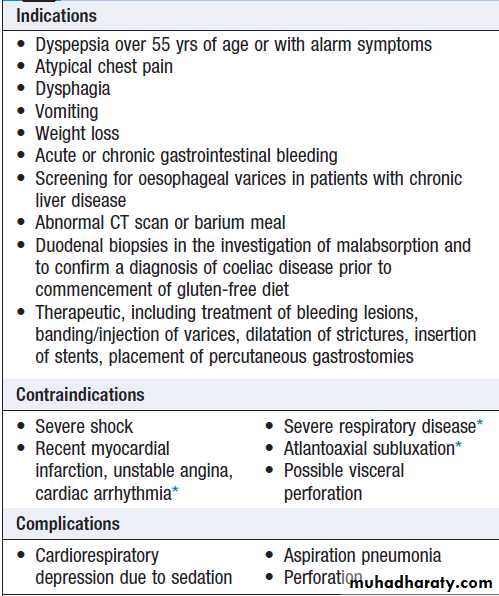

Endoscopy

Videoendoscopes provide high-definition imaging and accessories can be passed down the endoscope to allow both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

This is performed under light intravenous benzodiazepine

sedation, or using only local anaesthetic throat

spray after the patient has fasted for at least 4 hours.

With the patient in the left lateral position, the entire

oesophagus (excluding pharynx), stomach and first two

parts of duodenum can be seen.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

*These are ‘relative’ contraindications; in experienced hands, endoscopycan be safely performed.

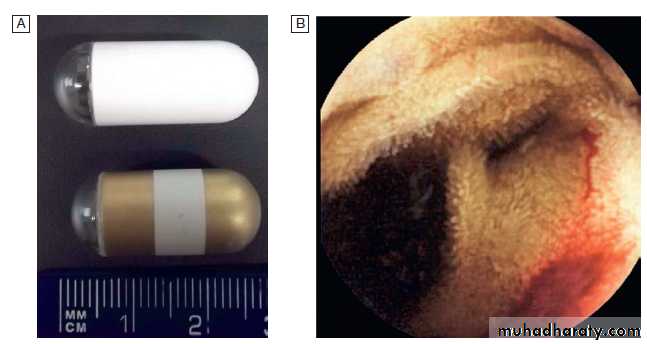

Wireless capsule endoscopy.

A Examples of capsules.B image of bleeding jejunal vascular malformation.

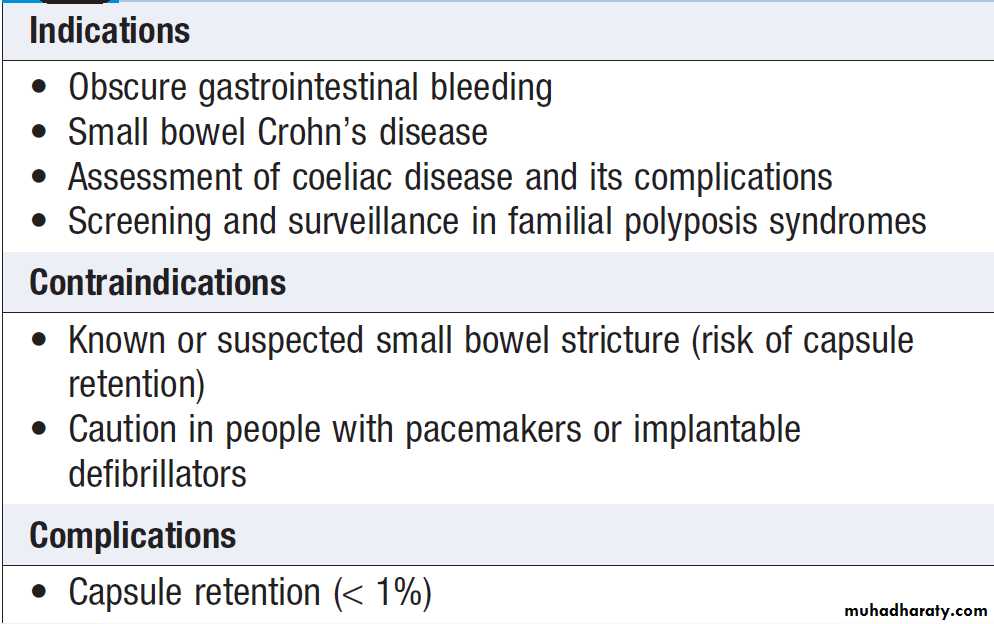

Capsule endoscopy

Capsule endoscopy uses a capsule containing an imaging device, battery, transmitter and antenna; as it traverses the small intestine, it transmits images to a battery-powered recorder worn on a belt round the patient’s waist. After approximately 8 hours, the capsule is excreted. Images from the capsule are analysed as a video sequence and it is usually possible to localise the segment of small bowel in which lesions are seen.

Abnormalities detected usually require enteroscopy for

confirmation and therapy.

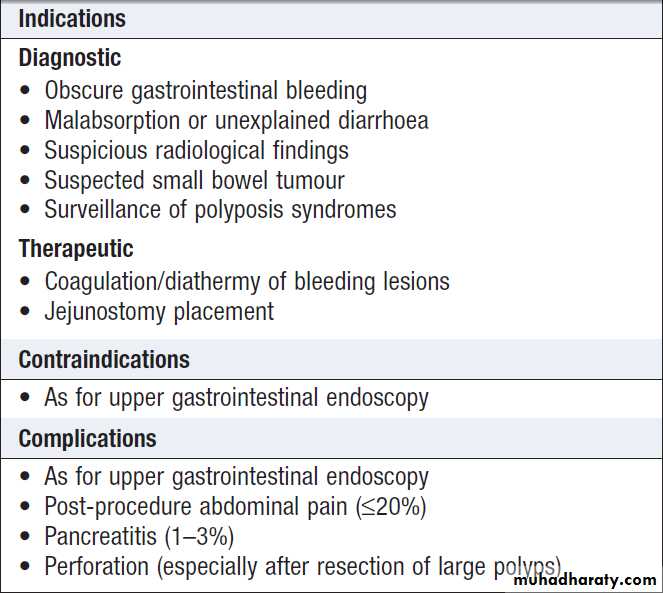

Double balloon enteroscopy

Double balloon enteroscopyUses a long endoscope with a flexible overtube. Sequential and repeated inflation and deflation of balloons on the tip of the overtube and enteroscope allow the operator to push and pull along the entire length of the small intestine to the terminal ileum, in order to diagnose or treat small bowel lesions detected by capsule endoscopy or other imaging modalities.

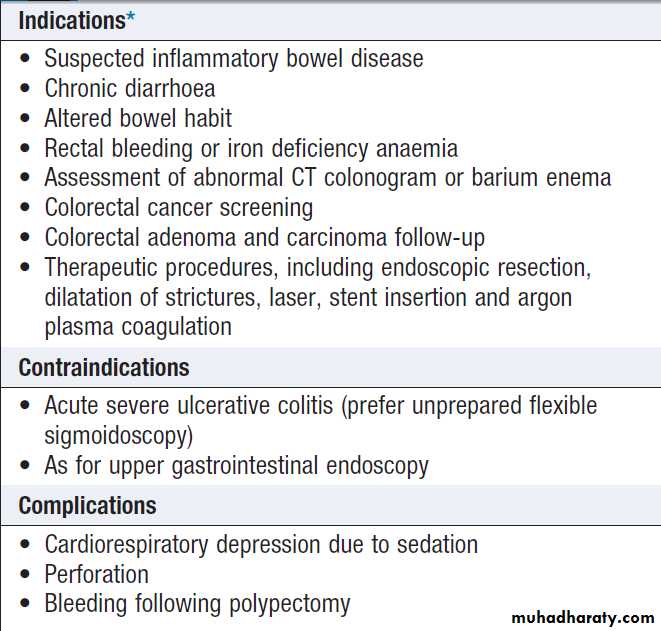

Colonoscopy

*Colonoscopy is not useful in the investigation of constipationSigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy

a 20 cm rigid plastic sigmoidoscope or in the endoscopy suite using a 60 cm flexible colonoscope following bowel preparation. Allow accurate detection of haemorrhoids, ulcerative colitis and distal colorectal neoplasia is possible. After full bowel cleansing, it is possible to examine the entire colon and the terminal

ileum using a longer colonoscope.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

(MRCP)has largely replaced endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in the evaluation of obstructive jaundice .

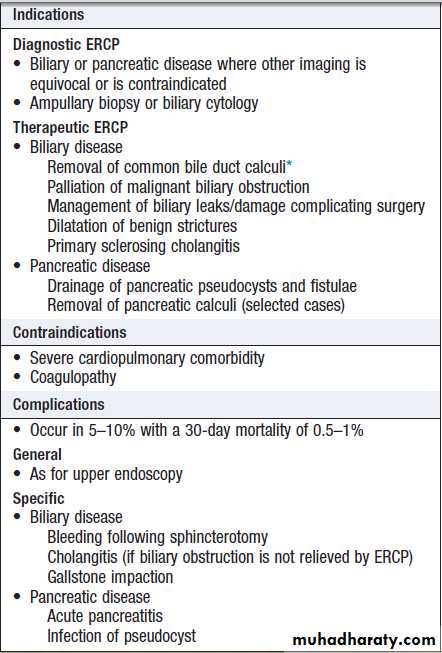

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

( ERCP)

Using a side-viewing duodenoscope, it is possible to

cannulate the main pancreatic duct and common bile duct. Nowadays, ERCP is mainly used in the treatment of a range of biliary and pancreatic diseases that have been identified by other techniques such as MRCP, EUS and CT.

Endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)*Laparoscopic surgery is preferred in fit individuals who also require

cholecystectomy.

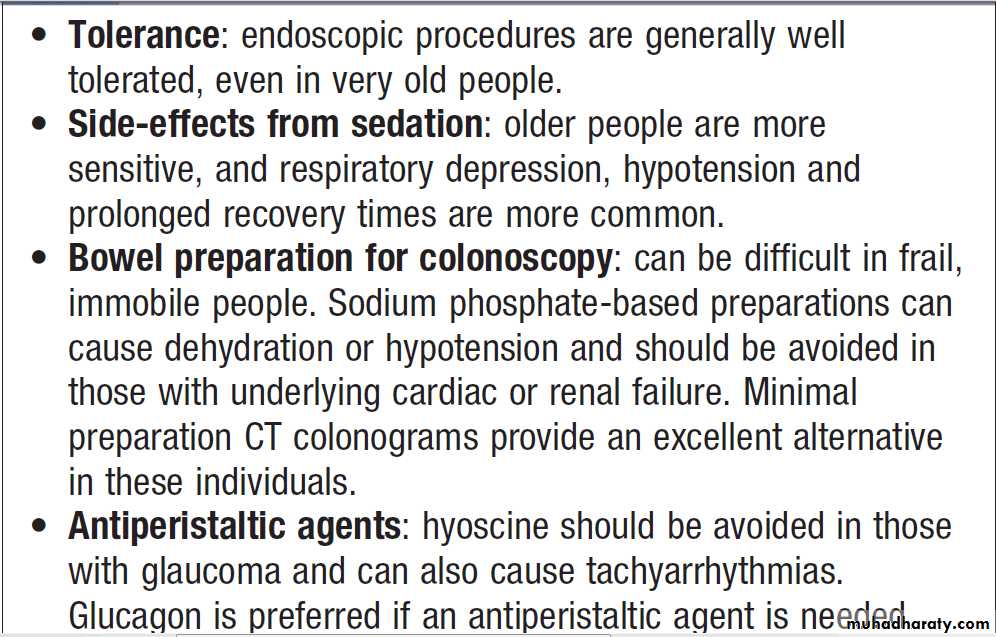

Endoscopy in old age

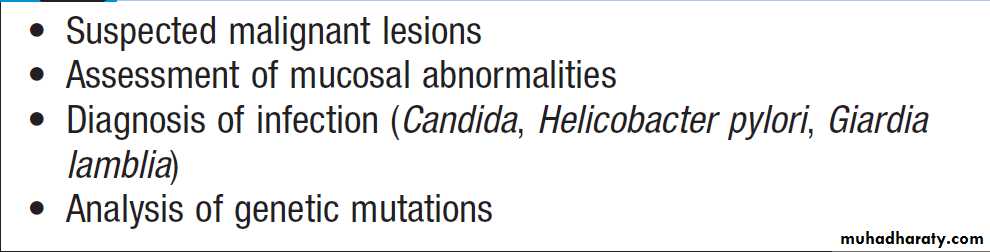

Reasons for biopsy or cytological examination

HistologyBiopsy material obtained during endoscopy or percutaneously can provide useful information

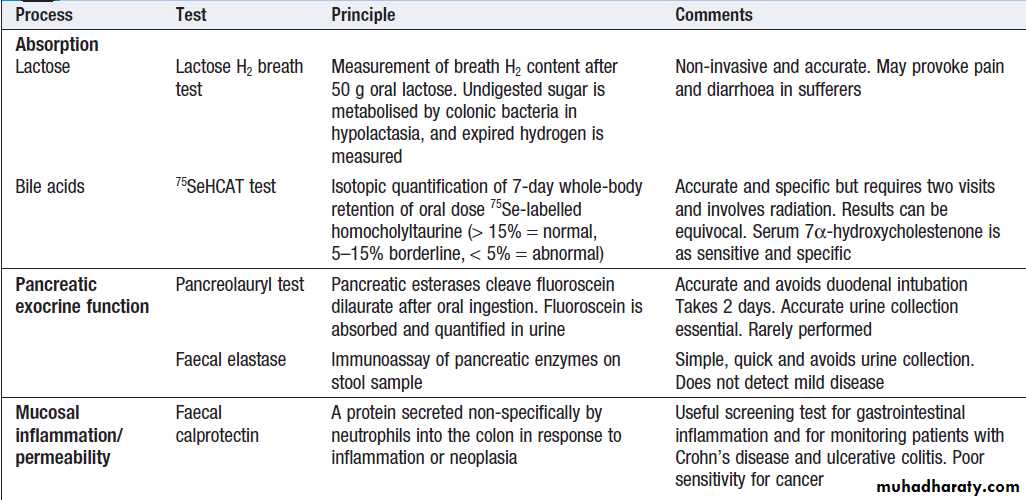

Tests of function

A number of dynamic tests can be used to investigateaspects of gut function, including digestion, absorption,

inflammation and epithelial permeability. In the

assessment of suspected malabsorption, blood tests

(full blood count, ESR, C-reactive protein (CRP), folate, vitamin B12, iron status, albumin, calcium and phosphate) are essential, and endoscopy is undertaken to obtain mucosal biopsies. Faecal calprotectin is very sensitive at detecting mucosal inflammation.

Dynamic tests of gastrointestinal function

Oesophageal motilityA barium swallow can give useful information about

oesophageal motility. Videofluoroscopy, with joint

assessment by a speech and language therapist and a

radiologist, may be necessary in difficult cases. Oesophageal manometry , often in conjunction with 24-hour pH measurements, is of value in diagnosing cases of refractory gastro- oesophageal reflux, achalasia and non-cardiac chest pain.

Gastric emptying

This involves administering a test meal containing solids and liquids labelled with different radioisotopes and measuring the amount retained in the stomach

Afterwards. It is useful in the investigation of suspected delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis).

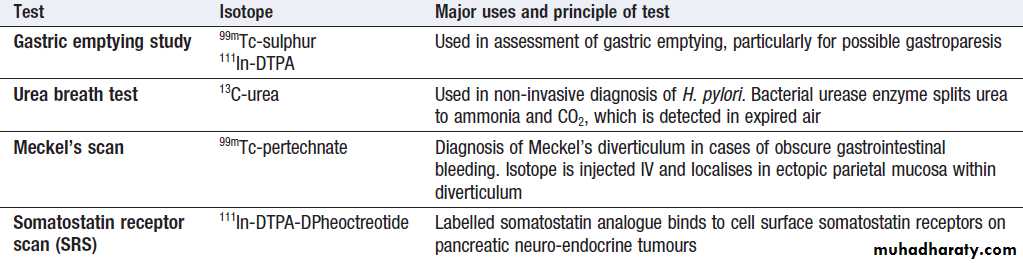

Commonly used radioisotope tests in gastroenterology

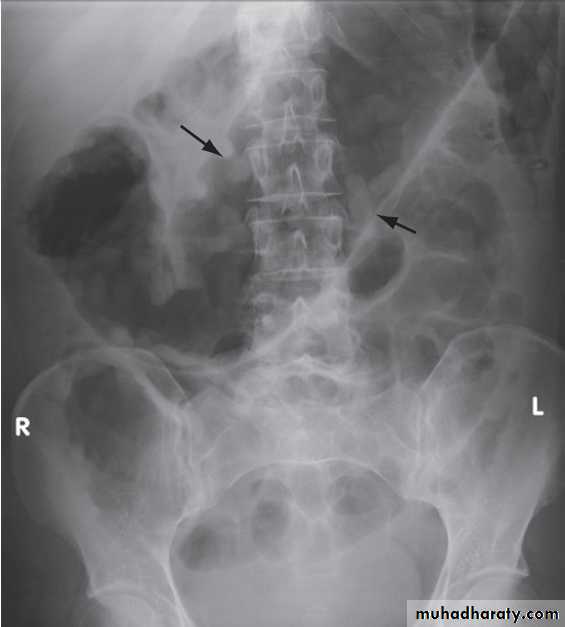

Colonic and anorectal motilityA plain abdominal X-ray taken on day 5 after ingestion of inert plastic pellets on days 1–3 gives an estimate of whole gut transit time. The test is useful in the evaluation of chronic constipation, when the position of any retained pellets can be observed, and helps to differentiate cases of slow transit from those due to obstructed defecation.

Radioisotope tests

Different radioisotope are used , information is obtained, such as the localisation of a Meckel’s diverticulum, rate of gastric emptying. Yet others are tests of infection and rely on the presence of bacteria to hydrolyse a radio-labelled test substance followed by detection of the radioisotope in expired air, such as the urea breath test for H. pylori.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS IN GI DISEASE

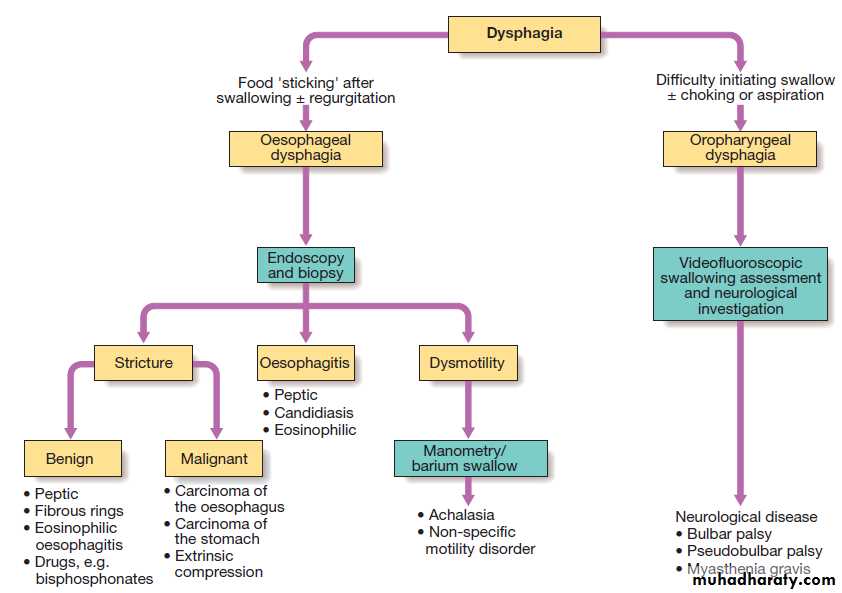

Dysphagia is defined as difficulty in swallowing. It may

coexist with heartburn or vomiting but should be distinguished from both globus sensation (in which

anxious people feel a lump in the throat without organic cause) and odynophagia (pain during swallowing, usually from gastro- oesophageal reflux or candidiasis).

Dysphagia can occur due to problems in the oropharynx

or oesophagus . Drooling, dysarthria, hoarseness and cranial nerve or other neurological signs may be present. Oesophageal disorders cause dysphagia by obstructing the lumen or by affecting motility.

Patients with oesophageal disease complain of food ‘sticking’ after swallowing.

Investigations

Dysphagia should always be investigated urgently.Endoscopy is the investigation of choice because it

allows biopsy and dilatation of strictures. If no abnormality is found, then barium swallow with videofluoroscopic swallowing assessment is indicated to detect major motility disorders. In some, oesophageal manometry is required.

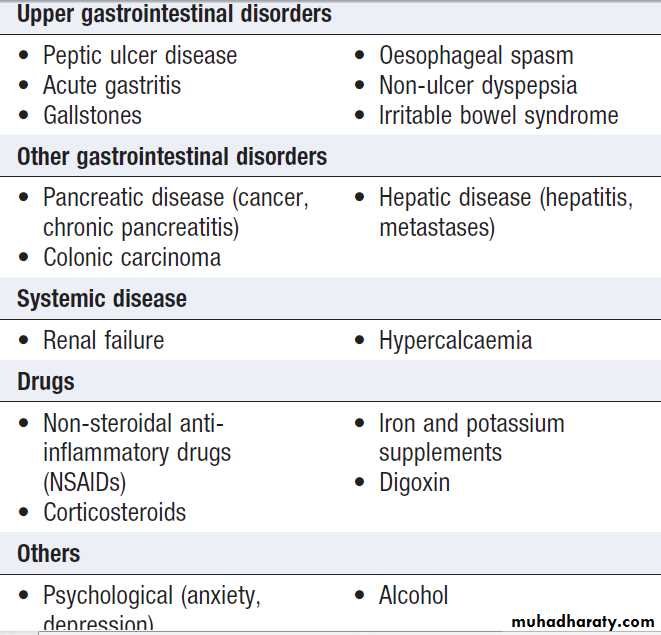

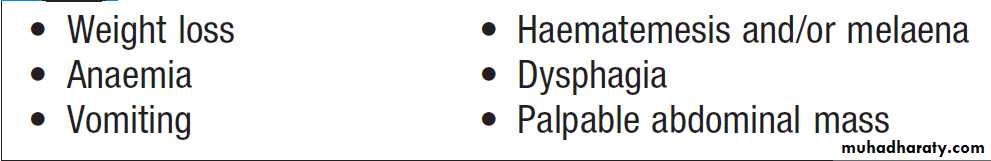

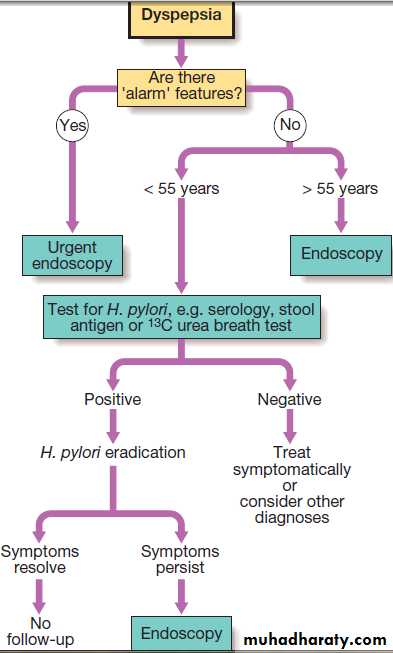

Dyspepsia symptoms such as discomfort, bloating and nausea.

Heartburn and other ‘reflux’ symptoms are separate entities, a careful history is important to detect ‘alarm’ features requiring urgent investigation and to detect atypical symptoms which might be due to problems outside the gastrointestinal tract.

Investigation of dysphagia.

Causes of dyspepsia

Alarm features in dyspepsia

Investigation of dyspepsia

Heartburn and regurgitationHeartburn describes retrosternal, burning discomfort,

often rising up into the chest and sometimes accompanied by regurgitation of acidic or bitter fluid into the throat. These symptoms often occur after meals, on lying down or with bending, straining or heavy lifting. They are classical of gastro-oesophageal reflux but up to 50% of patients present with other symptoms, such as chest pain, belching, halitosis, chronic cough or sore throats.

In young patients with typical symptoms and a good

response to dietary changes, antacids or acid suppression,

investigation is not required, but in patients over

55 years of age, those with alarm symptoms or atypical

features, urgent endoscopy is necessary.

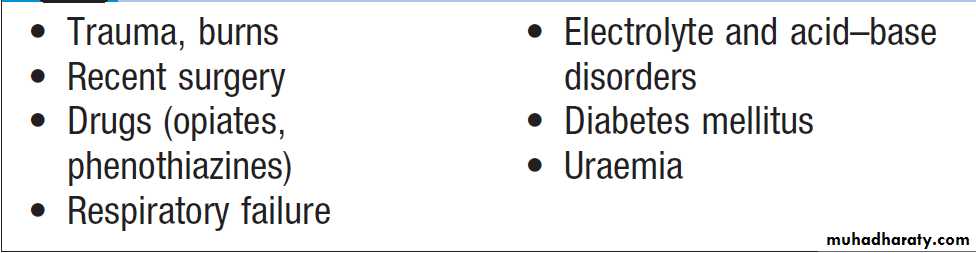

Vomiting

Vomiting is a complex reflex involving both autonomic and somatic neural pathways. Synchronous contraction of the diaphragm, intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles raises intra-abdominal pressure and, combined

with relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter,

results in forcible ejection of gastric contents.

It is important to distinguish true vomiting from regurgitation and to elicit whether the vomiting is acute or chronic (recurrent), as the underlying causes may differ.

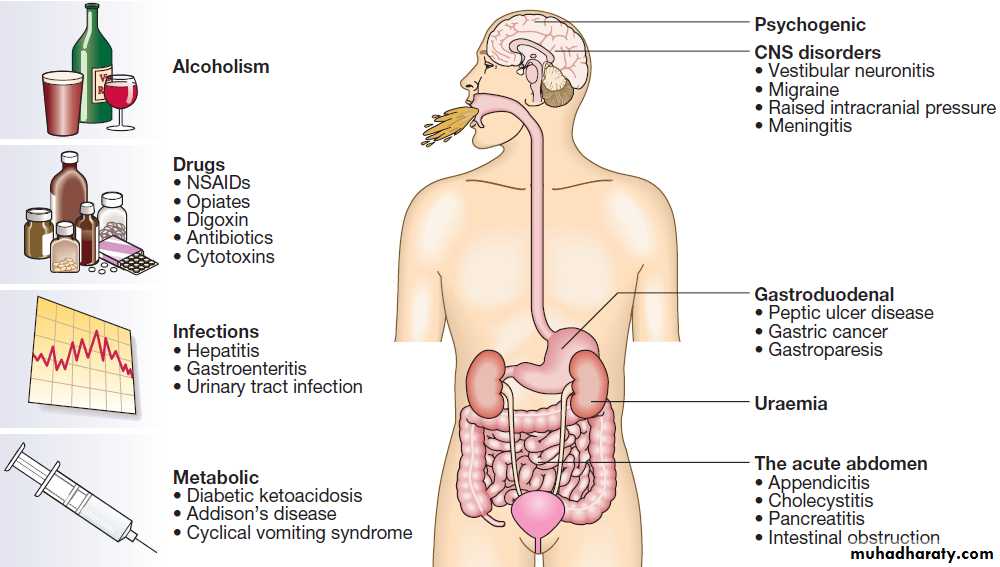

Causes of vomiting

Gastrointestinal bleedingAcute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage

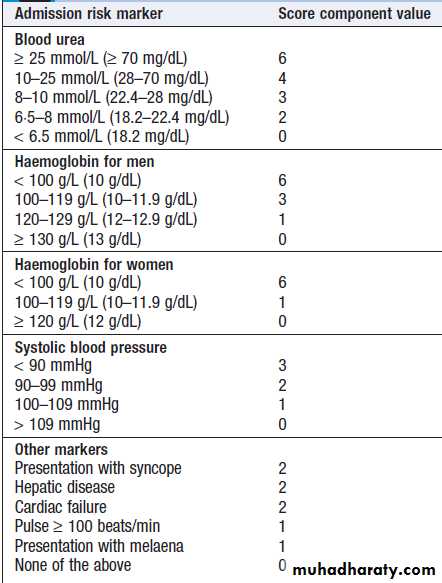

This is the most common gastrointestinal emergency. The mortality of patients admitted to hospital is about 10% but there is some evidence that outcome is better when patients are treated in specialised units. Risk scoring systems have been developed to stratify risk of needing endoscopic therapy or a poor outcome .The advantage of the Blatchford score is that it may be used before

endoscopy to predict the need for intervention to treat

bleeding. Low scores (2 or less) are associated with

a very low risk of adverse outcome.

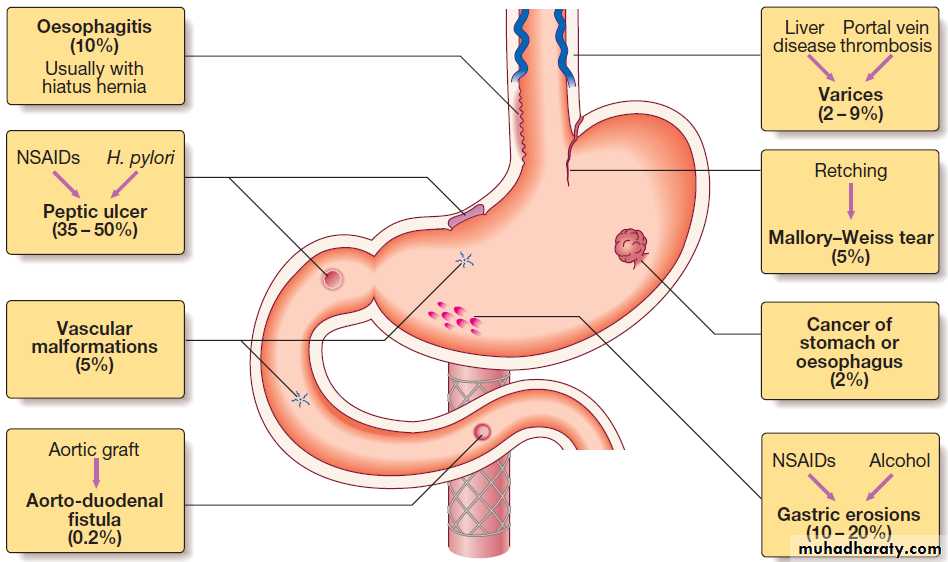

Causes of acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

Clinical assessment

Haematemesis is red with clots when bleeding is rapidand profuse, or black (‘coffee grounds’) when less

severe. Syncope may occur and is due to hypotension

from intravascular volume depletion. Symptoms of

anaemia suggest chronic bleeding.

Melaena is the passage of black, tarry stools containing altered blood; it is usually caused by bleeding from the upper GI tract, although haemorrhage from the right side of the colon is occasionally responsible. The characteristic colour and smell are the result of the action of digestive enzymes and bacteria upon haemoglobin. Severe acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding can sometimes cause maroon or bright red stool.

Management

1. Intravenous access.The first step is to gain IV access.2. Initial clinical assessment

• Define circulatory status. tachycardia, hypotension , oliguria, cold , sweating, and may be agitated.

• Seek evidence of liver disease ,Jaundice, cutaneous stigmata, hepatosplenomegaly and ascites.

• Identify comorbidity, cardiorespiratory, cerebrovascular or renal disease is important, because these may be worsened by acute bleeding and they increase the hazards of endoscopy and surgical operations. These factors can be combined using the Blatchford score. A score of < 3 is associated with a good prognosis, while progressively higher scores are associated with poorer outcomes.

3. Basic investigations

• Full blood count. Chronic or subacute bleeding leads to anaemia, but the haemoglobin concentration may be normal after sudden, major bleeding until haemodilution occurs. Thrombocytopenia may be a clue to the presence of hypersplenism in chronic liver disease.• Urea and electrolytes. For evidence of renal failure. The blood urea rises as the absorbed products of luminal blood are metabolised by the liver; an elevated blood urea with normal creatinine concentration implies severe bleeding.

• Liver function tests. For evidence of chronic liver disease.

• Prothrombin time. liver disease or anticoagulated patients.

• Cross-matching. 2 units of blood cross-matched.

4. Resuscitation

IV crystalloid fluids should be given to raise the blood pressure, and blood should be transfused when the patient is actively bleeding with low blood pressure and tachycardia. Comorbidities should be managed as appropriate. Patients with suspected chronic liver disease should receive broad-spectrum antibiotics. Central venous pressure (CVP) monitoring may be useful in severe bleeding, particularly in patients with cardiac disease.

5. Oxygen

This should be given to all patients in shock.

6. Endoscopy

This should be carried out after adequate resuscitation,

ideally within 24 hours.

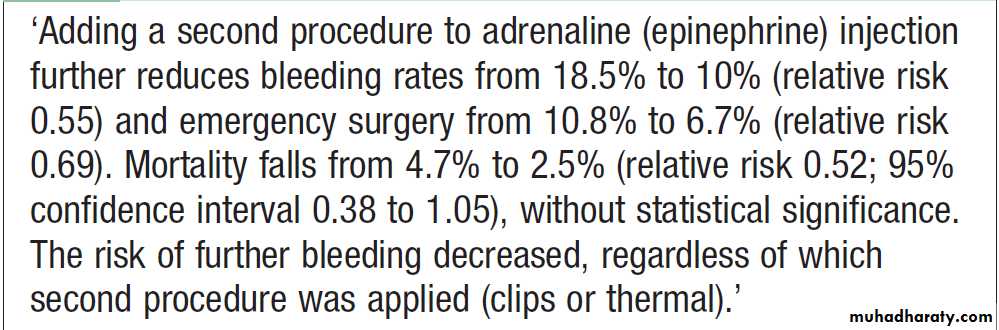

Patients who are found to have major endoscopic stigmata of recent haemorrhage can be treated endoscopically using a thermal or mechanical modality, such as a ‘heater probe’ or endoscopic clips, combined with injection of dilute adrenaline into the bleeding point (‘dual therapy’).

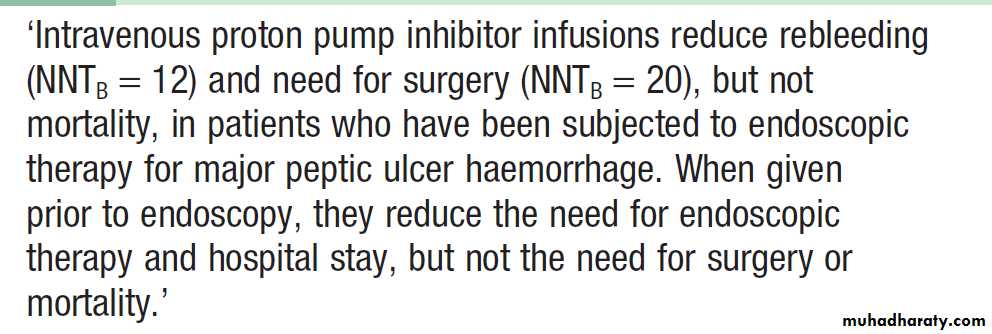

This may stop active bleeding and, combined

with intravenous proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, prevent rebleeding, thus avoiding the need for surgery .

Patients found to have bled from varices should be treated by band ligation.

7. Monitoring

Patients closely observed, with hourly measurements of pulse, blood pressure and urine output.

8. Surgery

indicated when endoscopic haemostasis fails to stop bleeding and if rebleeding occurs on one occasion in an elderly, frail patient, or twice in a younger, fitter patient.If available, angiographic embolisation is an effective alternative to surgery in frail patients.

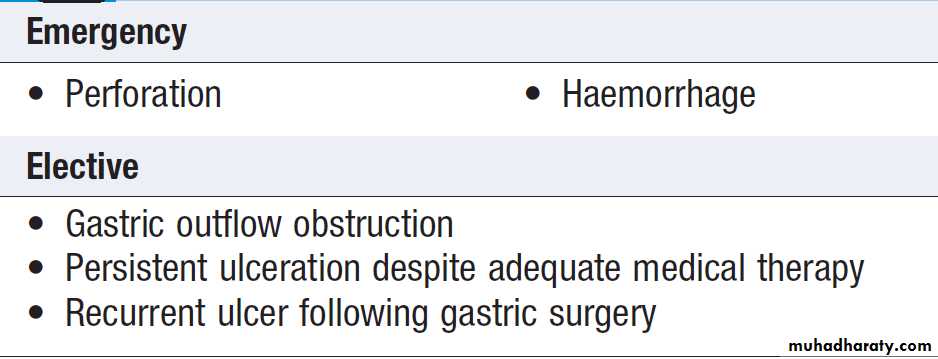

Duodenal ulcers treated by under-running, with or without pyloroplasty. Under-running for gastric ulcers can also be carried out (a biopsy taken to exclude carcinoma).

Local excision may be performed, but when neither is possible, partial gastrectomy is required. Following surgery, should be treated with H. pylori eradication if they test positive for it, and should avoid NSAIDs.

Successful eradication should be confirmed by urea breath or faecal antigen testing.

Modified Blatchford score: risk

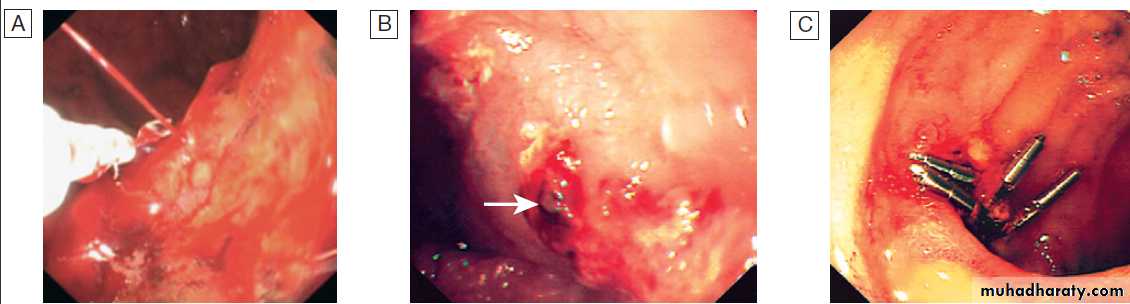

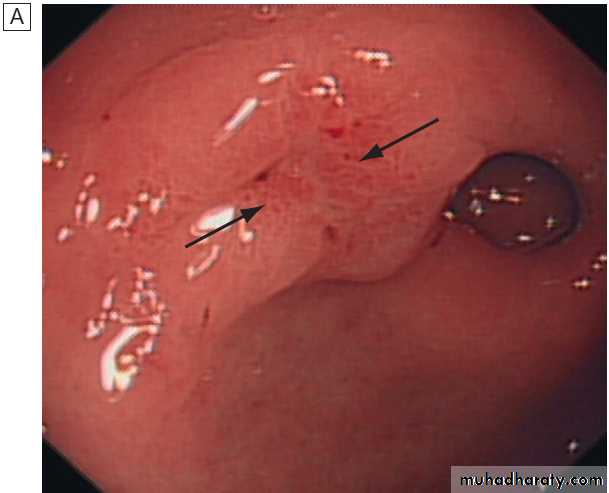

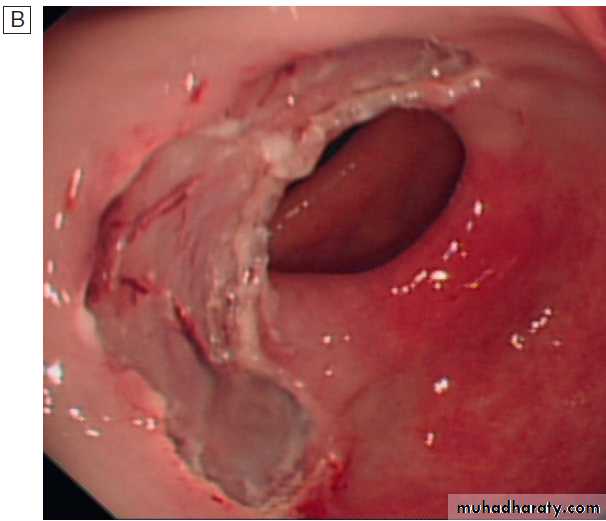

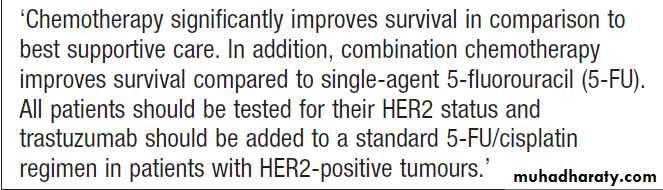

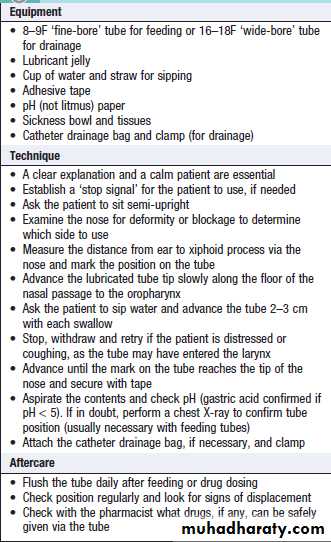

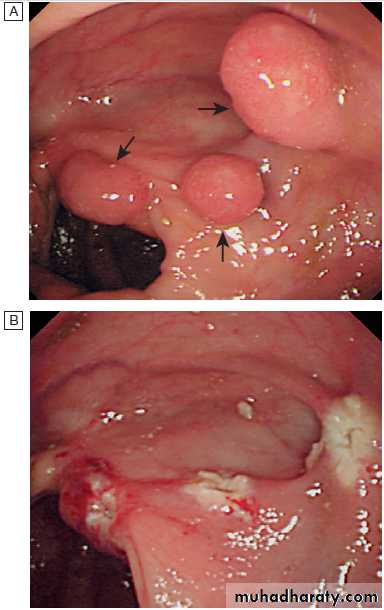

stratification in acute upper GI bleedingMajor stigmata of recent haemorrhage and endoscopic treatment. A Active arterial spurting from a gastric ulcer. An endoscopic

clip is about to be placed on the bleeding vessel. When associated with shock, 80% of cases will continue to bleed or rebleed.

B ‘Visible vessel’ (arrow).

In reality, this is a pseudoaneurysm of the feeding artery seen here in a pre-pyloric peptic ulcer. It carries a 50% chance of rebleeding.

C Haemostasis is achieved after endoscopic clipping of the bleeding vessel in the duodenum.

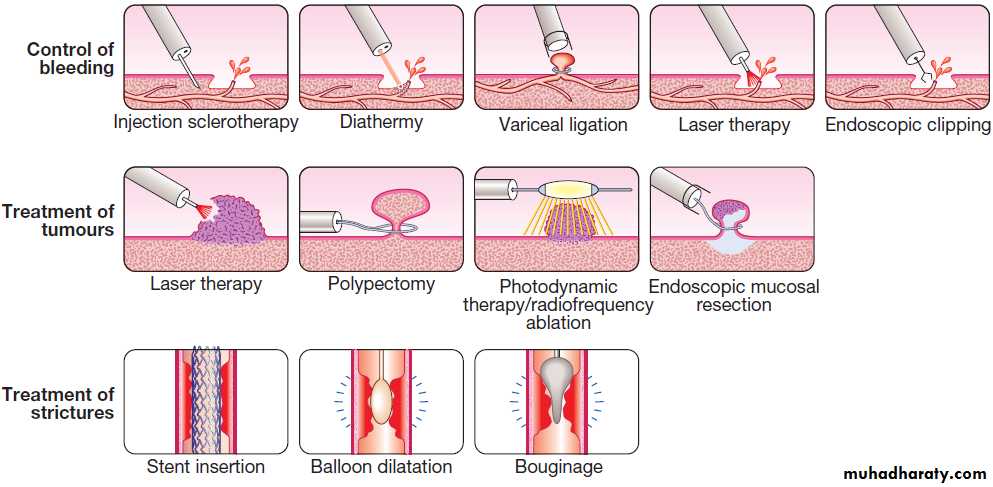

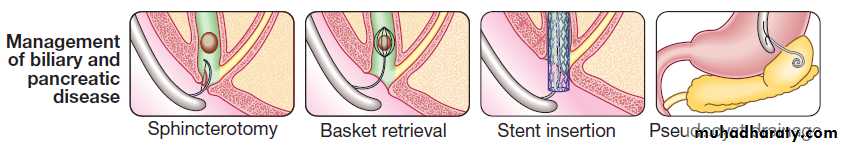

Examples of therapeutic techniques in endoscopy

Single versus dual modality endoscopic therapy in high-risk bleeding ulcers

Adjunctive drug therapy for bleeding ulcers

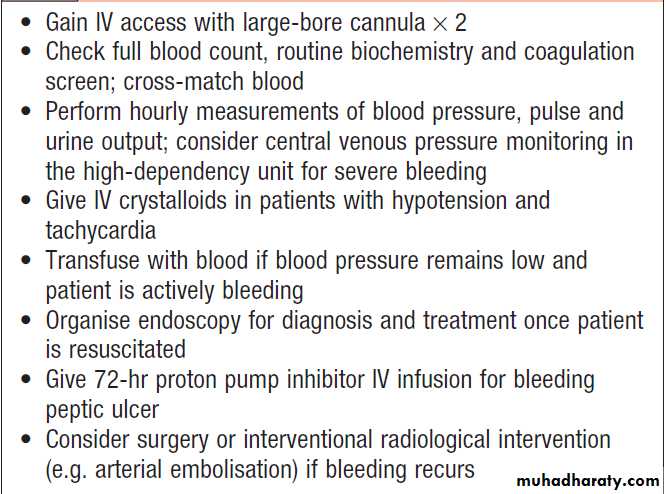

Emergency management of acute non- variceal upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage

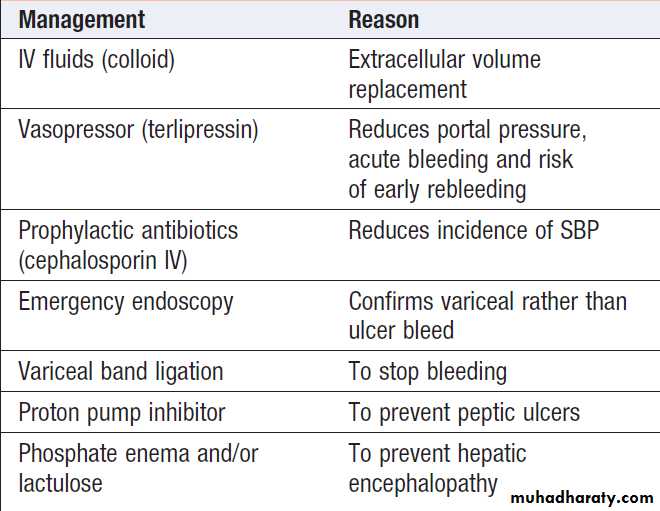

Emergency management of variceal bleeding

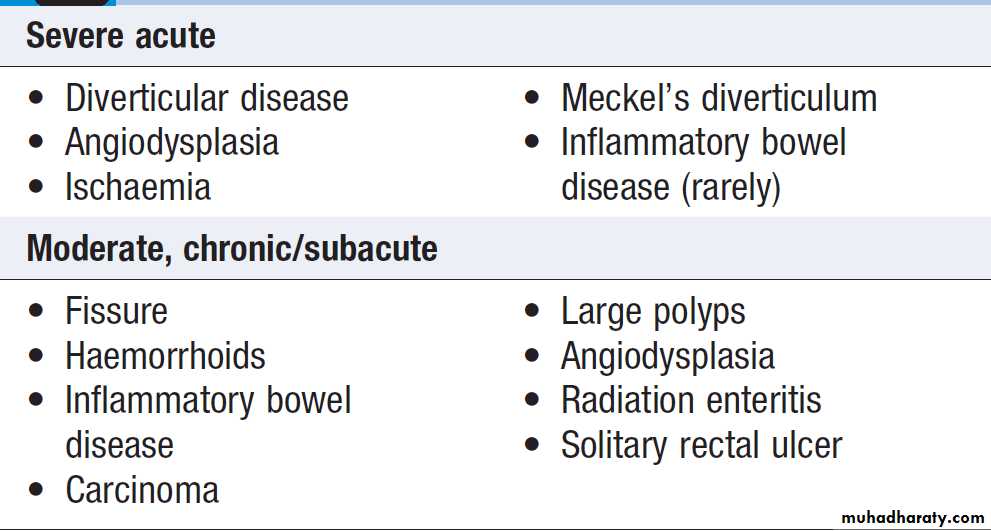

Causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding

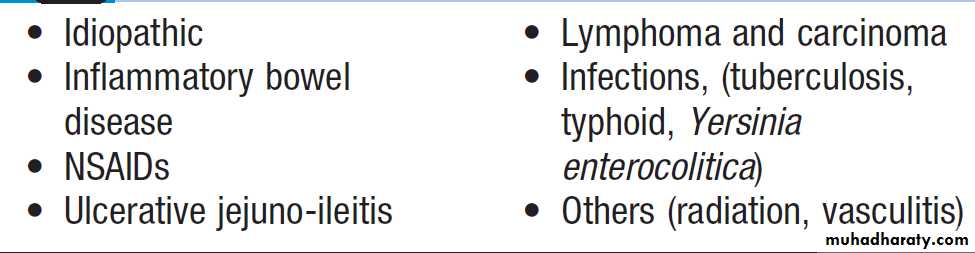

This may be due to haemorrhage from the colon, anal canal or small bowel.Severe acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Profuse red or maroon diarrhoea and shock. Diverticular disease is the most common cause (erosion of an artery within the mouth of a diverticulum). Bleeding almost always stops spontaneously, but if it does not, the diseased segment of colon should be resected after confirmation by angiography or colonoscopy. Angiodysplasia is a disease of the elderly, in which vascular malformations develop in the proximal colon. Bleeding can be profuse; it usually stops spontaneously but commonly recurs. Diagnosis is often difficult. Colonoscopy may reveal vascular spots and, in the acute phase,visceral angiography can show bleeding.

In some, diagnosis is only achieved by laparotomy with on-table colonoscopy. The treatment of choice is endoscopic thermal ablation, but resection of the affected bowel may be required if bleeding continues. Bowel ischaemia due to occlusion of the inferior mesenteric artery can present with abdominal colic and rectal bleeding, considered in elderly (generalised atherosclerosis). The diagnosis is made at colonoscopy. Resection is required in the presence of peritonitis. Meckel’s diverticulum with ectopic gastric epithelium may ulcerate and erode into a major artery.

The diagnosis should be considered in children or adolescents who present with profuse or recurrent lower GI bleeding. A Meckel’s 99mTc-pertechnate scan is sometimes positive but the diagnosis is commonly made only by laparotomy, at which time the diverticulum is excised.

Subacute or chronic lower gastrointestinal bleeding

This can occur at all ages and is usually due to haemorrhoids (bleeding is bright red and occurs during or after defecation) or anal fissure, fresh rectal bleeding and anal pain occur during defecation. Proctoscopy can be used to make the diagnosis but subjects who have altered bowel habit and those who present > 40 years should undergo colonoscopy to exclude colorectal cancer.Major gastrointestinal bleeding of unknown cause

In some who present with major GI bleeding, upper endoscopy and colonoscopy fail to reveal a diagnosis.When severe life-threatening bleeding continues,

urgent CT mesenteric angiography is indicated.

This will usually identify the site if the bleeding > 1 mL/min and then formal angiographic embolisation can often stop the bleeding. If angiography is negative or bleeding is less severe, push or double balloon enteroscopy can visualise the small intestine and treat the bleeding source. Wireless capsule endoscopy is often used. When all else fails, laparotomy with on-table endoscopy is indicated.

Chronic occult gastrointestinal bleeding

Occult means that blood or its breakdown products are present in the stool but cannot be seen by the naked eye. Occult bleeding may reach 200 mL per day and cause iron deficiency anaemia. Any cause of GI bleeding may be responsible but the most important is colorectal cancer, particularly caecum, which may produce no GI symptoms.

In clinical practice, investigation of the upper and lower GIT should be considered whenever a patient presents with unexplained iron deficiency anaemia. Testing the stool for the presence of blood is unnecessary and should not influence whether or not the GIT is imaged because bleeding from tumours is often intermittent and a negative faecal occult blood (FOB) test does not exclude the diagnosis. The only value of FOB testing is as a means of population screening for colonic neoplasia in asymptomatic individuals .

Jejunal angiodysplastic lesion seen at enteroscopy in a patient with recurrent obscure bleeding.

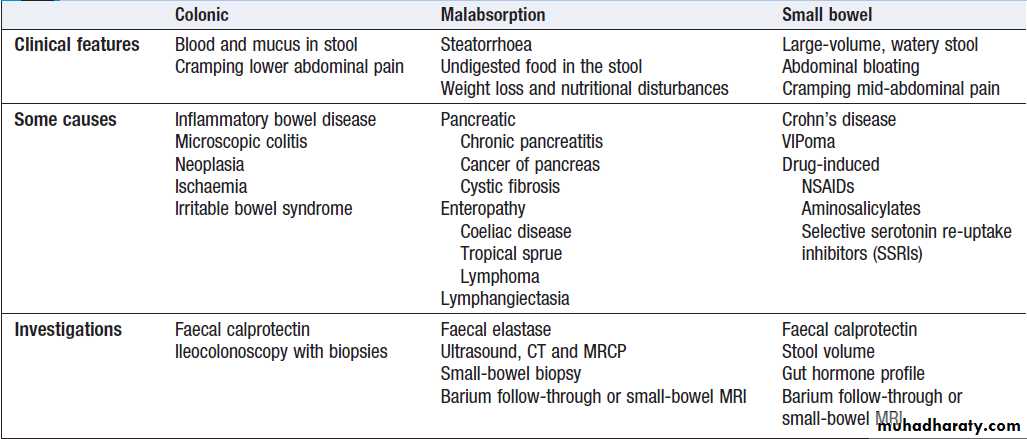

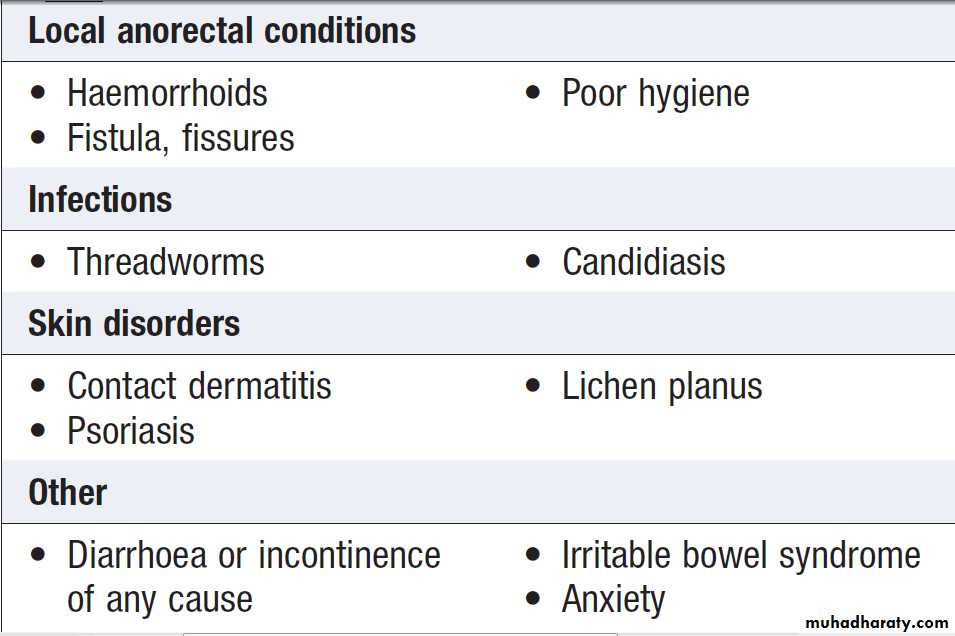

Diarrhoea

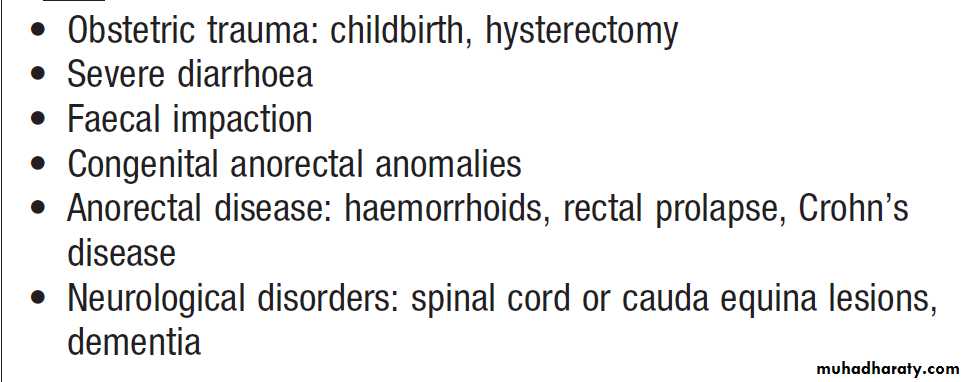

The passage of > 200 g of stool daily. The most severe symptom in many is urgency of defecation, and faecal incontinence is a common event.Acute diarrhoea

This is extremely common and is usually due to faecal–

oral transmission of bacteria or their toxins, viruses or

Parasites. Infective is usually short-lived <10 days .

A variety of drugs, antibiotics, cytotoxic, PPIs and NSAIDs, may be responsible.

Chronic or relapsing diarrhoea

The most common is irritable bowel syndrome which can present with increased frequency of defecation and loose, watery or pellety stools. Diarrhoea rarely occurs at night and is most severe before and after breakfast.

At other times, the patient is constipated and there are other characteristic symptoms of IBS . The stool often contains mucus but never blood, 24-hour stool volume is < 200 g.

Chronic diarrhoea can be categorised as being due to

disease of the colon or small bowel, or to malabsorption.

Clinical presentation, examination of the stool, routine blood tests and imaging reveal a diagnosis in many cases.

Malabsorption

Diarrhoea and weight loss in patients with a normal dietis likely to be caused by malabsorption. A few

patients have apparently normal bowel habit but diarrhoea is usual and may be watery and voluminous.

Bulky, pale and offensive stools which float in the toilet

(steatorrhoea) signify fat malabsorption. Abdominal distension, borborygmi, cramps, weight loss and undigested food in the stool may be present. Some patients

complain only of malaise and lethargy. In others symptoms related to deficiencies of specific vitamins, trace elements and minerals may occur.

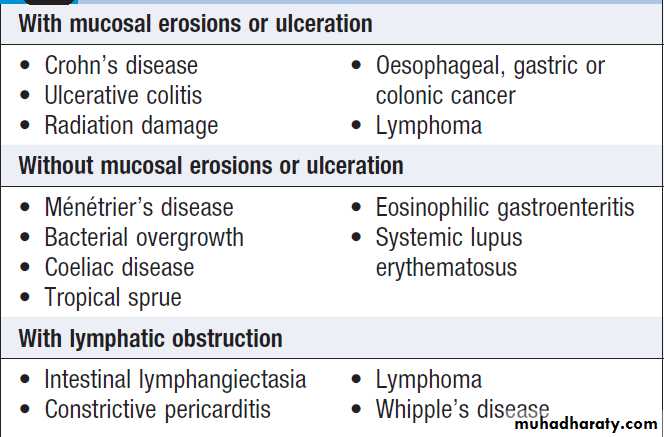

Pathophysiology

Malabsorption results from :

1. Intraluminal maldigestion occurs when deficiency of bile or pancreatic enzymes. Fat and protein malabsorption results, also occur with small bowel bacterial overgrowth.

2. Mucosal malabsorption results from small bowel resection or damage, diminishing the surface area for absorption and depleting brush border enzyme activity.

3. ‘Post-mucosal’ lymphatic obstruction prevents the uptake and transport of absorbed lipids into lymphatics. Increased pressure in these vessels results in leakage into the intestinal lumen, leading to protein-losing enteropathy.

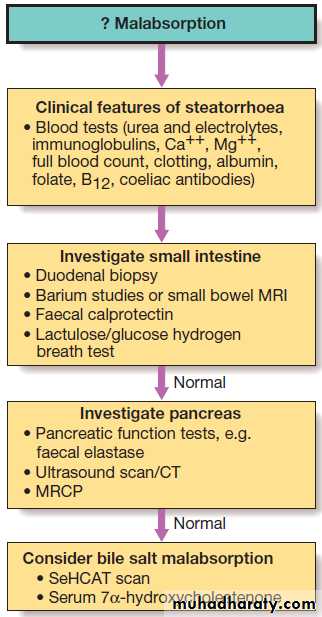

Investigations

Both to confirm the presence and the underlying cause.

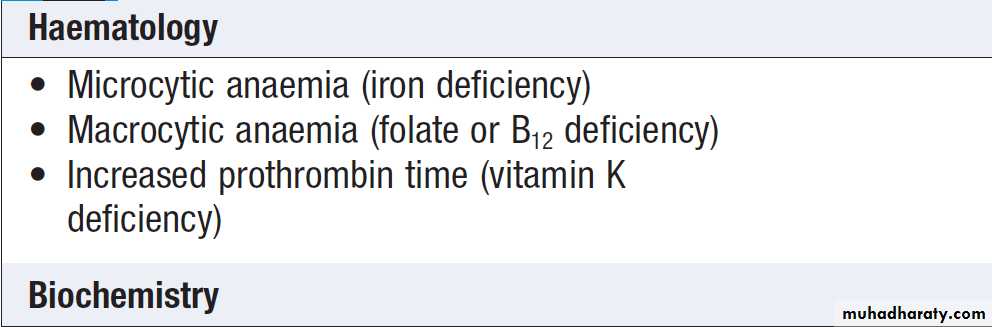

Blood tests may show one or more of the abnormalities.

Investigation for suspected malabsorption

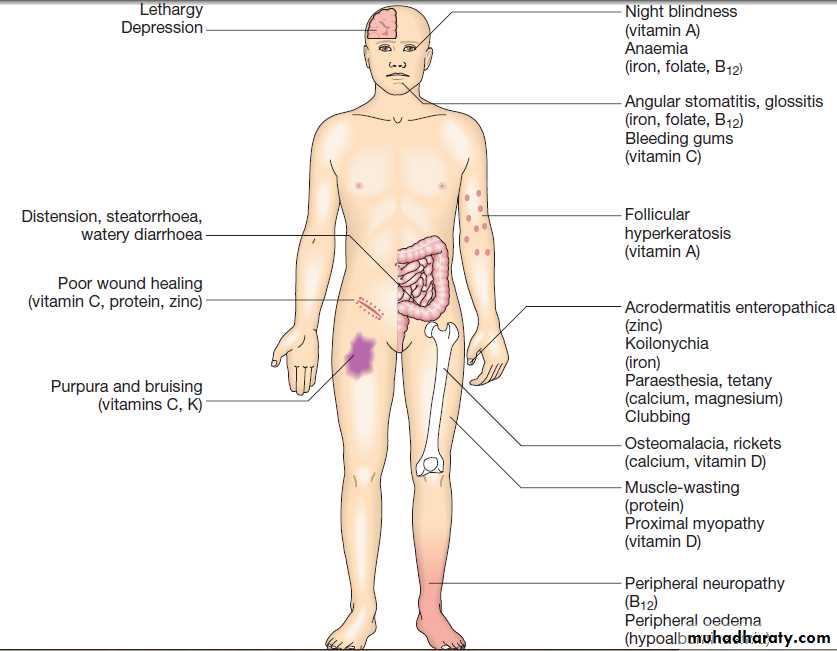

Routine blood test abnormalities in malabsorptionPossible physical consequences of malabsorption

Weight lossWeight loss may be physiological, due to dieting, exercise, starvation, or the decreased nutritional intake

which accompanies old age. Weight loss of more than

3 kg over 6 months is significant and often indicates the

presence of an underlying disease. Hospital and general

practice weight records may be valuable in confirming

that weight loss has occurred, as may reweighing

patients at intervals; sometimes weight is regained or

stabilises in those with no obvious cause.

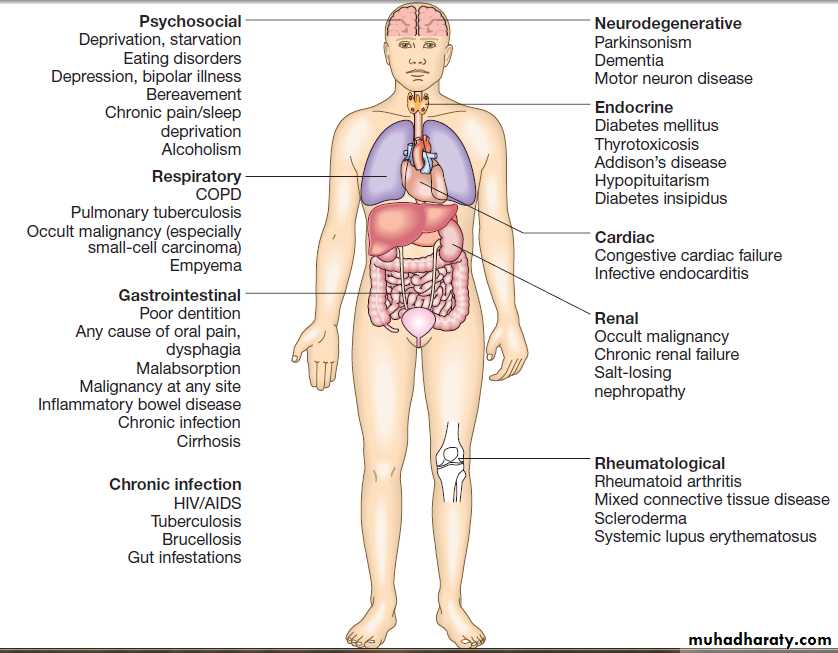

Pathological weight loss can be due to psychiatric illness, systemic disease, gastrointestinal causes or advanced disease of many organ systems .

Physiological

Weight loss can occur in the absence of serious disease in healthy individuals who have changes in physical activity or social circumstances. It may be difficult to be sure of this diagnosis in older patients, when the dietary history may be unreliable, and professional help from a dietitian is often valuable under these circumstances.

Psychiatric illness

Features of anorexia nervosa , bulimia and affective disorders may only be apparent

after formal psychiatric input. Alcoholic patients lose weight as a consequence of self-neglect and poor dietary intake. Depression may cause weight loss.

Systemic diseases

Chronic infections, including tuberculosis ,recurrent urinary or chest infections, and a range of parasitic and protozoan infections ,should be considered. A history of foreign travel, high-risk activities and specific features, such as fever, night sweats, rigors, productive cough and dysuria, must be sought. Promiscuous sexual activity and drug misuse suggestHIV-related illness .

Weight loss is a late feature of disseminated malignancy, but by the time the patient presents, other features of cancer are often present.

Chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid, and polymyalgia rheumatica ,are associated with weight loss.

Gastrointestinal disease

Almost any disease of the gastrointestinal tract can cause weight loss. Dysphagia and gastric outflow obstruction cause weight loss by reducing food intake. Malignancy at any site may cause weight loss by mechanical obstruction, anorexia or cytokine-mediated systemic effects. Malabsorption from pancreatic diseases or small bowel causes may lead to profound weight loss with specific nutritional deficiencies .Inflammatory diseases, such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis ,cause anorexia, fear of eating and loss of protein, blood and nutrients from the gut.

Metabolic disorders and miscellaneous causes

Weight loss may occur in association with metabolic disorders, end-stage respiratory and cardiac disease.

Investigations

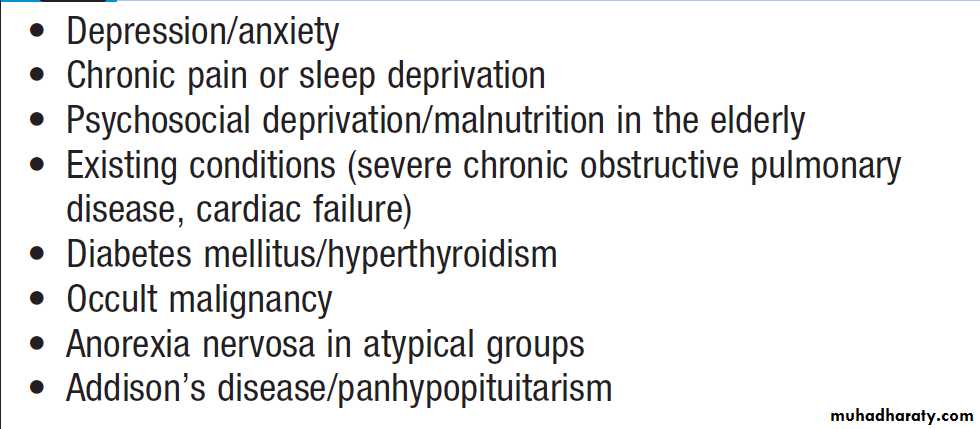

urinalysis for sugar, protein and blood; blood tests, including liver function tests, random blood glucose and thyroid function tests; CRP and ESR (may be raised in unsuspected infections, such as tuberculosis, connective tissue disorders and malignancy); and faecal calprotectin. Sometimes invasive tests, such as bone marrow aspiration or liver biopsy, may be necessary to identify conditions like cryptic miliary tuberculosis .Rarely, abdominal and pelvic imaging by CT may be necessary, but before embarking on invasive or very costly investigations, it is always worth revisiting the patient’s history and reweighing at intervals.Some important causes of weight loss

Some easily overlooked causes of

unexplained weight lossConstipation

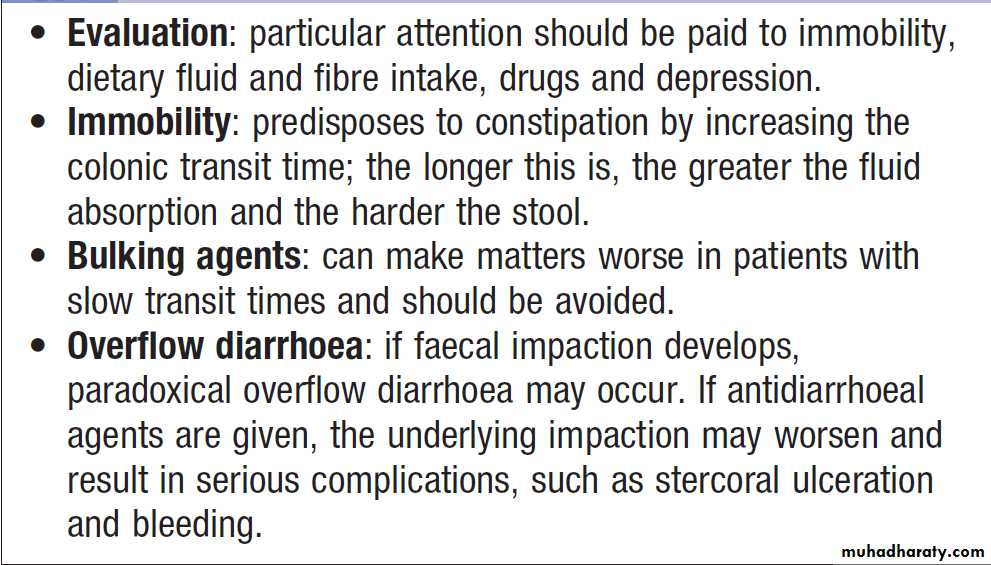

Constipation is defined as infrequent passage of hard stools. Patients may also complain of straining, a sensation of incomplete evacuation and either perianal or abdominal discomfort.Clinical assessment and management

The onset, duration and characteristics are important; for example, a neonatal onset suggests Hirschsprung’s disease, while a recent change in bowel activity in middle age should raise the suspicion of organic disorders, such as colonic carcinoma. The presence of rectal bleeding, pain and weight loss is important, as are excessive straining, symptoms suggestive of irritable bowel ,a history of childhood constipation and emotional distress.

Careful examination , search for general medical disorders, neurological disorders, especially spinal cord lesions, should be sought. Perineal inspection and rectal examination are essential and may reveal abnormalities of the pelvic floor (abnormal descent, impaired sensation), anal canal or rectum (masses, faecal impaction, prolapse). It is neither possible nor appropriate to investigate every person with constipation. Most respond to increased fluid intake, dietary fibre supplementation, exercise and the judicious use of laxatives.

Middle-aged or elderly with a short history or worrying symptoms (rectal bleeding, pain or weight loss) must be investigated promptly, by barium enema or colonoscopy.

Initial visit

Digital rectal examination, proctoscopy,sigmoidoscopy biochemistry, i serum calcium and thyroid function tests, and a full blood count should be done. If these are normal,a 1-month trial of dietary fibre and/or laxatives is justified.

Next visit

If symptoms persist, barium enema or CT colonography is indicated.

Further investigation

If no cause is found and disabling symptoms are present, then investigation of dysmotility may be necessary. The problem may be one of infrequent desire to defecate (‘slow transit’) or may result from neuromuscular incoordination and excessive straining (‘functional obstructive defecation’). Intestinal marker, anorectal manometry, electrophysiological studies and MR proctography can all be used.

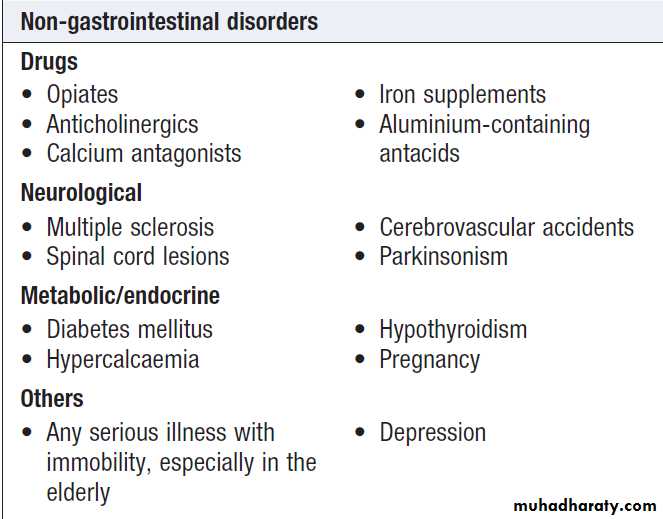

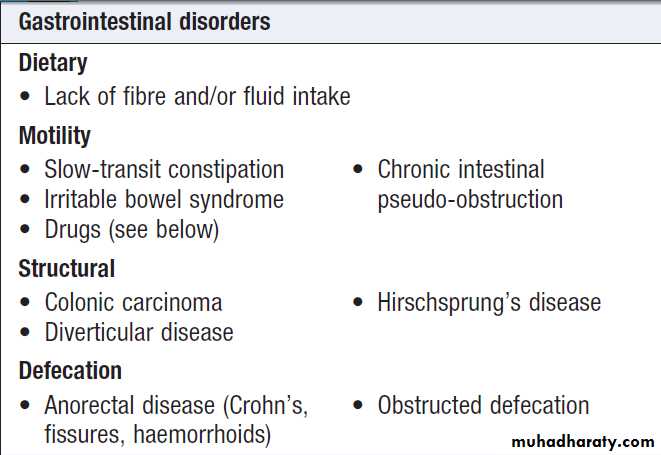

Causes of constipation

Abdominal pain

• Visceral. Gut organs are insensitive to stimuli suchas burning and cutting but are sensitive to distension, contraction, twisting and stretching. Pain from unpaired structures is usually but not always felt in the midline.

• Parietal. parietal peritoneum is innervated by somatic nerves, and its involvement by inflammation, infection or neoplasia causes sharp, well- localised.

• Referred pain. (For example, gallbladder pain is

referred to the back or shoulder tip.)

• Psychogenic. Cultural, emotional and psychosocial factors influence everyone’s experience of pain.

In some, no organic cause can be found despite investigation, and psychogenic causes (depression or somatisation disorder) may be responsible .

The acute abdomen

This accounts for approximately 50% of all urgentadmissions to general surgical units.

• Inflammation. Pain develops gradually, over several hrs.

It is initially rather diffuse until the parietal peritoneum is involved, when it becomes localised. Movement exacerbates the pain; rigidity and guarding occur.

• Perforation. When a viscus perforates, pain starts

abruptly; it is severe and leads to generalised peritonitis.

• Obstruction. Pain is colicky, with spasms which cause the patient to writhe around and double up.

Initial clinical assessment

If there are signs of peritonitis (guarding and rebound tenderness with rigidity), the patient should be resuscitated with oxygen, intravenous fluids and antibiotics.

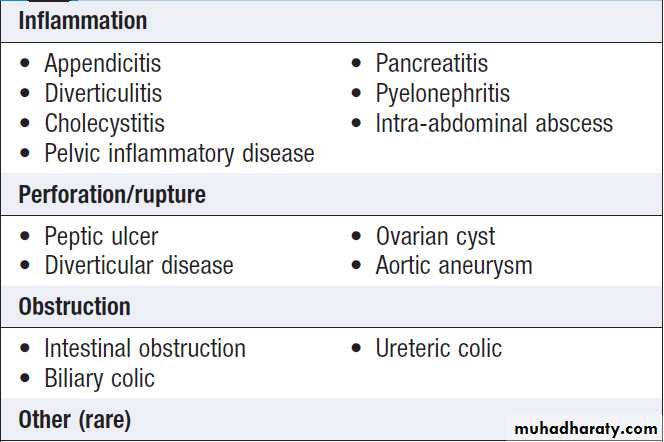

Causes of acute abdominal pain

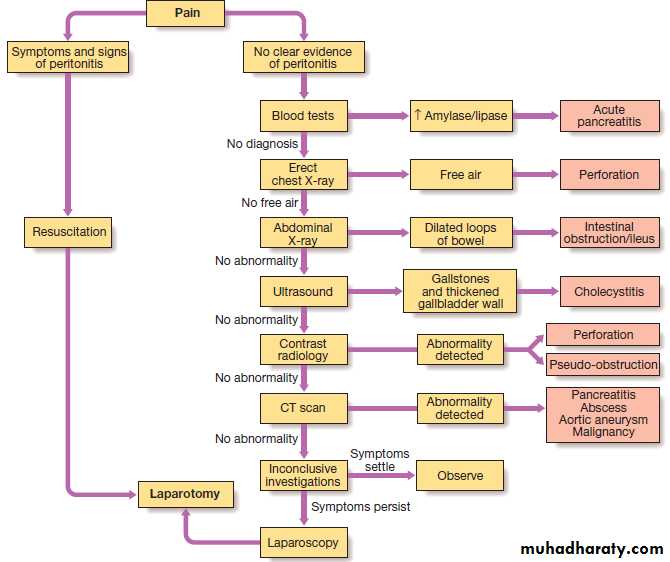

Management of acute abdominal pain:

an algorithmInvestigations

Full blood count, urea and electrolytes, amylase, leucocytosis. An erect chest X-ray may show air under the diaphragm, suggestive of perforation, and a plain abdominal film may show evidence of obstruction or ileus. An abdominal US may help if gallstones or renal stones are suspected also useful in the detection of free fluid and any possible intra-abdominal abscess. Contrast studies, by either mouth or anus, are useful in the further evaluation of intestinal obstruction, and essential in the differentiation of pseudo obstruction from mechanical large-bowel obstruction. Other investigations include CT(pancreatitis, retroperitoneal collections or masses, aortic aneurysm) and angiography (mesenteric ischaemia).

Diagnostic laparotomy should be considered when the diagnosis has not been revealed by other investigations.

All patients must be re-assessed (every 2–4 hours) so that any change in condition that might alter both the suspected diagnosis and clinical decision.

Management

The general approach is to close perforations, treat

inflammatory conditions with antibiotics or resection,

and relieve obstructions. The speed of intervention and the necessity for surgery depend on the organ that is involved and on a number of other factors, of which the presence or absence of peritonitis is the most important.

A treatment summary of some of the more common

surgical conditions follows.

Acute appendicitis

Treated by early surgery, since there is a risk of perforation and recurrent attacks with nonoperative treatment, can be removed through a conventional right iliac fossa incision or by laparoscopic techniques.

Acute cholecystitis

This can be successfully treated non-operatively but the high risk of recurrence and the low morbidity of surgery have made early laparoscopic cholecystectomy the treatment of choice.

Acute diverticulitis

Conservative therapy is standard but if perforation has occurred, resection is advisable. Depending on peritoneal contamination and the state of the patient, primary anastomosis is preferable to a Hartmann’s procedure (oversew of rectal stump and end colostomy).

Small bowel obstruction

If the cause is obvious and surgery inevitable (such aswith a strangulated hernia), an early operation is appropriate. If the suspected cause is adhesions from previous surgery, only those patients who do not resolve within the first 48 hours or who develop signs of strangulation (colicky pain becomes constant, peritonitis, tachycardia, fever, leucocytosis) should have surgery.

Large bowel obstruction

Pseudo-obstruction should be treated non-operatively.

Some patients benefit from colonoscopic decompression, but mechanical obstruction merits resection, usually with a primary anastomosis. Differentiation between the two is made by water-soluble contrast enema.

Perforated peptic ulcer

Surgical closure of the perforation is standard practice but some patients without generalised peritonitis can be treated non-operatively once a water-soluble contrast has confirmed spontaneous sealing of the perforation. Adequate and aggressive resuscitation with IV fluids, antibiotics and analgesia is mandatory before surgery.Chronic or recurrent abdominal pain

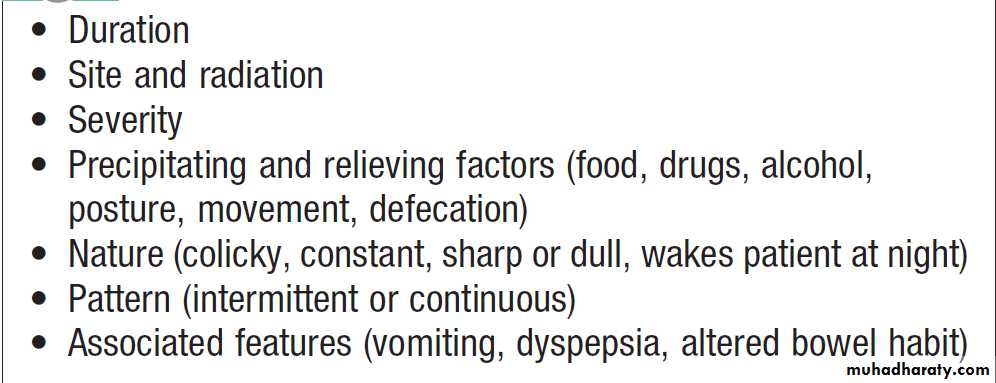

It is essential to take a detailed history, paying particular attention to features of the pain and any associated symptoms .

Note should be made of the patient’s general demeanour, mood and emotional state, signs of weight loss, fever, jaundice or anaemia.

If a thorough abdominal and rectal examination is normal, a careful search should be made for evidence of disease affecting other structures, particularly the vertebral column, spinal cord, lungs and cardiovascular system.

Investigations will depend on the clinical features

elicited during the history and examination:

• Endoscopy and US for epigastric pain, dyspepsia and symptoms suggestive of gallbladder disease

• Colonoscopy is indicated for patients with altered bowel habit, rectal bleeding or features of

obstruction suggesting colonic disease.

• CT or MR angiography , considered when pain is provoked by food in a patient with widespread atherosclerosis, may indicate mesenteric ischaemia.

• Persistent symptoms require exclusion of colonic or

small bowel disease. Blood tests, faecal calprotectin and sigmoidoscopy) are sufficient in the absence of rectal bleeding, weight loss and abnormal physical findings.

• US , CT and faecal elastase for patients with upper abdominal pain radiating to the back. A history of alcohol misuse, weight loss and diarrhoea suggests chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer.

• Recurrent attacks of pain in the loins radiating to

the flanks with urinary symptoms should prompt

investigation for renal or ureteric stones by

abdominal X-ray, ultrasound and CT urography.

• A past history of psychiatric disturbance, repeated negative investigations or vague symptoms which do not fit any disease or organ pattern suggest a psychological origin for the pain .

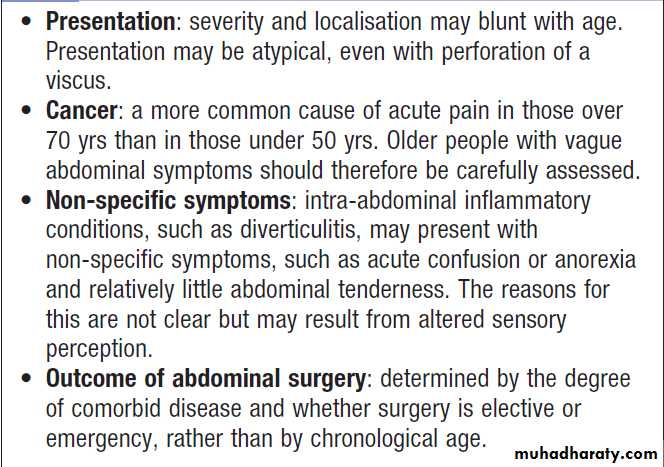

Acute abdominal pain in old age

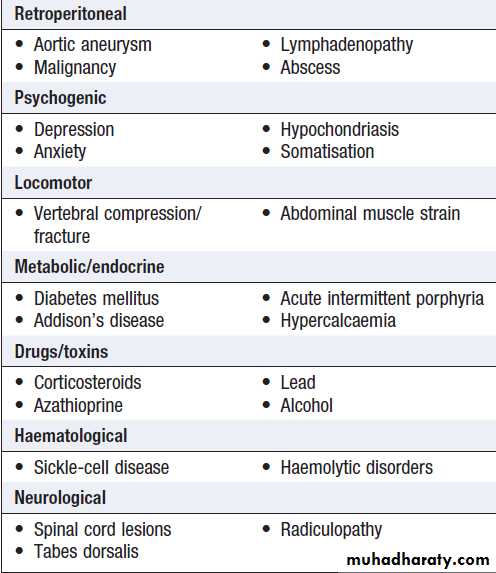

Extra-intestinal causes of chronic or

recurrent abdominal painHow to assess abdominal pain

Constant abdominal painPatients with chronic pain that is constant or nearly always present usually have features to suggest the underlying diagnosis. In a minority, no cause will be found, despite thorough investigation, leading to the diagnosis of ‘chronic functional abdominal pain’. In these patients, there appears to be abnormal CNS processing of normal visceral afferent sensory input, psychosocial factors are often , and the most important tasks are to provide symptom control, if not relief, and to minimise the effects of the pain on social, personal and occupational life. Patients are best managed in specialised pain clinics where, in addition to psychological support, appropriate use of drugs, including tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin or pregabalin, ketamine and opioids, may be necessary.

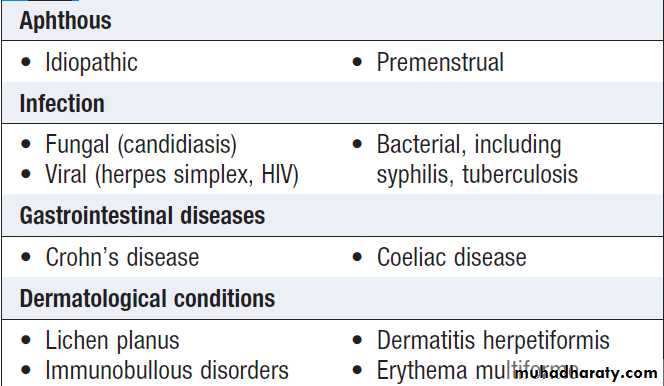

Aphthous ulceration

Superficial and painful; in any part of the mouth. Recurrent up to 30% ,common in women prior to menstruation. The cause is unknown, severe cases other causes must be considered .Occasionally, biopsy is necessary.Candidiasis

The yeast Candida albicans is a normal mouth commensal

may proliferate to cause thrush. This occurs in babies, debilitated, corticosteroid or antibiotic, diabetic and immunosuppressed. White patches are seen on the tongue and buccal mucosa. Odynophagia or dysphagia suggests pharyngeal and oesophageal candidiasis.

Oral thrush treated with nystatin or amphotericin suspensions or lozenges. Resistant cases or immunosuppressed may require oral fluconazole

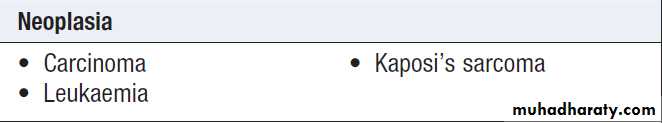

Causes of oral ulceration

Causes of oral ulceration'cont'd

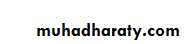

Oral cancer

Squamous carcinoma of the oral cavity is common .The mortality rate is around 50%, largely as a result of late diagnosis. Poor diet, alcohol excess and smoking or tobacco chewing are the traditional risk factors but high-risk, oncogenic strains of human papillomavirus (HPV-16 and HPV-18) have been identified as responsible for much of the recent increase in incidence, especially in cases affecting the base of tongue, soft palate and tonsils. Patients with suspicious lesions , all possible sources of local trauma or infection treated and should be reviewed after 2 weeks, with biopsy if the lesion persists. Small cancers can be resected but extensive surgery, with neck dissection to remove involved lymph nodes, may be necessary.

Some patients can be treated with radical radiotherapy alone, and sometimes given after surgery to treat microscopic residual disease. Some tumours may be amenable to photodynamic therapy (PDT).

Symptoms and signs of oral cancer

Parotitis

Due to viral or bacterial infection. Mumps causes a self-limiting acute parotitis . Bacterial usually occurs as a complication of major surgery, a consequence of dehydration and poor oral hygiene. Patients present with painful parotid swelling and can be complicated by abscess formation. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are required, surgical drainage is necessary for abscesses.

• Infection : Mumps. Bacterial (post-operative)

• Calculi

• Sjِgren’s syndrome

• Sarcoidosis

• Tumours

Benign: pleomorphic adenoma (95% of cases) Intermediate: mucoepidermoid tumour Malignant: carcinoma

Causes of salivary gland swelling

Oral health in old age

Factors associated with the development of

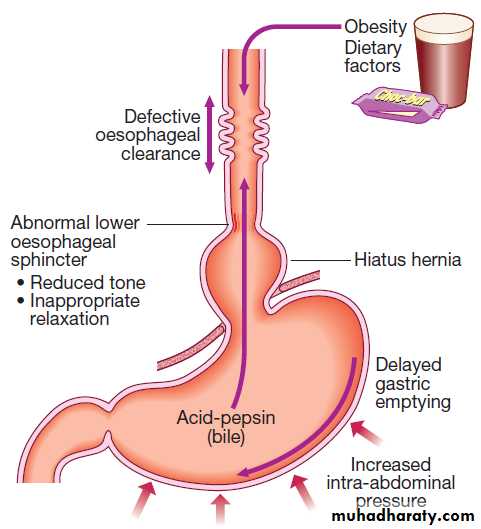

gastro-esophagealreflux disease.

Dietary fat, chocolate, alcohol and coffee relax the lower oesophageal sphincter and may provoke symptoms.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Affects approximately 30% of general population. Pathophysiology

Occasional episodes are common in healthy individuals. Reflux is normally followed by oesophageal peristaltic waves which efficiently clear the gullet, alkaline saliva neutralises residual acid, and symptoms do not occur. Gastro- oesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

develops when the oesophageal mucosa is exposed to gastroduodenal contents for prolonged periods of time, resulting in symptoms and, in a proportion of cases, oesophagitis. Several factors are known to

be involved in the development of GERD .

Abnormalities of the lower oesophageal sphincter

The lower sphincter is tonically contracted under normal circumstances, relaxing only during swallowing.Some patients with GERD have reduced lower oesophageal sphincter tone, permitting reflux when intra-abdominal pressure rises. In others, basal sphincter tone is normal but reflux occurs in response to frequent episodes of inappropriate sphincter relaxation.

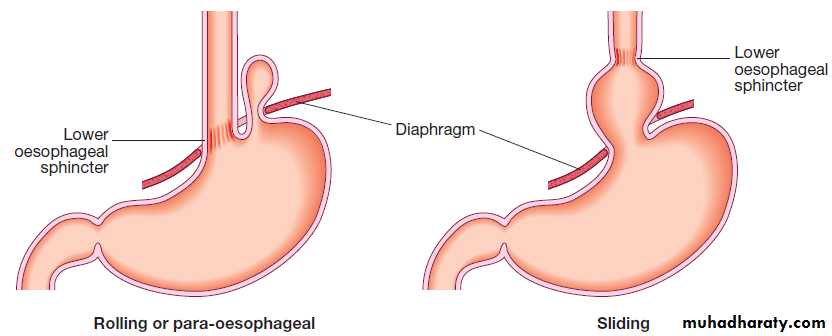

Hiatus hernia

Causes reflux because the pressure gradient between the abdominal and thoracic cavities, which normally pinches the hiatus, is lost. In addition, the oblique angle between the cardia and oesophagus disappears. Almost all who develop oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagus or strictures have a hiatus hernia.

Delayed oesophageal clearance

Defective peristaltic activity found in patients who have oesophagitis. It is a primary abnormality, since it persists after oesophagitis has been healed by acid-suppressing drug therapy. Poor clearance increase acid exposure time.Gastric contents

Gastric acid is important oesophageal irritant and there is a close relationship between acid exposure time and symptoms. Pepsin and bile also contribute to mucosal injury.

Defective gastric emptying

In patients with GERD. The reason is unknown.

Increased intra-abdominal pressure

Pregnancy and obesity are established predisposing

causes. Weight loss may improve symptoms.

Dietary and environmental factors

Dietary fat, chocolate, alcohol and coffee relax the lower oesophageal sphincter and may provoke symptoms.

Patient factors

Visceral sensitivity and patient vigilance play a role in

determining symptom severity.

Clinical features

The major symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation,

often provoked by bending, straining or lying down.

‘Waterbrash’, which is salivation due to reflex salivary

gland stimulation as acid enters the gullet, is often

present. The patient is often overweight. Some are woken at night by choking as refluxed fluid irritates the larynx. Others develop odynophagia or dysphagia.

Atypical chest pain which may be severe and can mimic angina, and may be due to reflux-induced oesophageal spasm. Others include hoarseness (‘acid laryngitis’), recurrent chest infections, chronic cough and asthma.

Complications of GERD

1.Oesophagitis

Mild redness to severe, bleeding ulceration with stricture formation, are recognised, although appearances may be completely normal . There is a poor correlation between

symptoms and histological and endoscopic findings.

2. Barrett’s oesophagus

pre-malignant, the normal squamous lining of the lower oesophagus is replaced by columnar mucosa (columnar lined oesophagus( CLO)) that may contain areas of intestinal metaplasia .

It is an adaptive response to chronic GERD and is found in 10% undergoing gastroscopy for reflux symptoms. The condition is often asymptomatic until discovered with oesophageal cancer. The relative risk of oesophageal cancer is 40–120-fold increased but the absolute risk is low (0.1–0.5% per year). The epidemiology and aetiology

of CLO are poorly understood. It is more common in men, obese and those >50 years of age. It is weakly associated with smoking but not alcohol intake. The risk of cancer seems to relate to the severity and duration rather than the presence of CLO per se and it has been suggested that duodenogastrooesophageal reflux of bile, pancreatic enzymes and pepsin, as well as gastric acid, may be important in pathogenesis.

Diagnosis. This requires multiple systematic biopsies to

detect intestinal metaplasia and/or dysplasia.

Management.

Neither potent acid suppression nor antireflux surgery stops progression of CLO, and treatment is only indicated for symptoms of reflux or complications, such as stricture. Endoscopic therapies, radiofrequency ablation or photodynamic therapy, can induce regression but, at present, are used only for those with dysplasia or intramucosal cancer. Regular endoscopic surveillance can detect dysplasia at an early stage and may improve survival but, because most CLO is undetected until cancer develops, surveillance strategies are unlikely to influence the overall mortality rate of oesophageal cancer.

Surveillance is expensive and cost-effectiveness studies have been conflicting, but it is currently recommended that patients with CLO without dysplasia should undergo endoscopy at 3–5-yearly intervals and those with lowgrade dysplasia at 6–12-monthly intervals.

For those with high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or intramucosal carcinoma, the treatment options are either

oesophagectomy or endoscopic therapy with a combination

of endoscopic resection (ER) of any visibly abnormal

areas and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the

remaining Barrett’s mucosa as an ‘organ-preserving’

alternative to surgery.

3. Anaemia

Iron deficiency anaemia can occur as a consequence ofoccult blood loss from long-standing oesophagitis. Most

patients have a large hiatus hernia and bleeding can

stem from subtle erosions in the neck of the sac (‘Cameron lesions’). Nevertheless, hiatus hernia is very common and other causes, particularly colorectal cancer, must be considered, even when endoscopy reveals oesophagitis.

4. Benign oesophageal stricture

Fibrous strictures can develop as a consequence of longstanding oesophagitis. The typical presentation is with dysphagia that is worse for solids than for liquids.

A history of heartburn is common but not invariable; many elderly patients presenting with strictures have no preceding heartburn. Diagnosis is by endoscopy,

Biopsies taken to exclude malignancy. Endoscopic balloon dilatation is helpful. Subsequently, long-term therapy with a PPI drug at full dose should be started. The patient should be advised to chew food thoroughly, and it is important to ensure adequate dentition.

5. Gastric volvulus

Occasionally, a massive intrathoracic hiatus hernia may

twist upon itself, leading to a gastric volvulus. This gives rise to complete oesophageal or gastric obstruction and

presents with severe chest pain, vomiting and dysphagia. The diagnosis is made by chest X-ray (air bubble in the chest) and barium swallow. Most cases spontaneously resolve but recurrence is common, and surgery is usually advised after the acute episode has been treated by nasogastric decompression.

Investigations

Young patients who present with typical symptoms ofgastro-oesophageal reflux, without worrying features such as dysphagia, weight loss or anaemia, can be treated empirically without investigation. Investigation is advisable if patients present over the age of 50–55 years, if symptoms are atypical or if a complication is suspected. Endoscopy is the investigation of choice. This is performed to exclude other upper GIT diseases that can mimic GERD and to identify complications. A normal endoscopy in a patient with compatible symptoms should not preclude treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

Twenty-four-hour pH monitoring is indicated if the

diagnosis is unclear or surgical intervention is underconsideration. This involves tethering a slim catheter

with a terminal radiotelemetry pH-sensitive probe

above the gastro-oesophageal junction. The intraluminal

pH is recorded whilst the patient undergoes normal

activities, and episodes of symptoms are noted and

related to pH. A pH of less than 4 for more than 6–7%

of the study time is diagnostic of reflux disease. In a few

patients with difficult reflux, impedance testing can

detect weakly acidic or alkaline reflux that is not revealed by standard pH testing.

Management

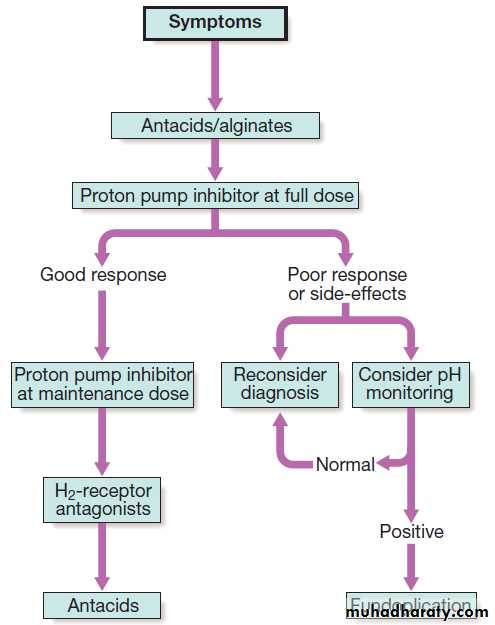

A treatment algorithm for gastro- oesophageal reflux is outlined in Figure . Lifestyle advice, including

weight loss, avoidance of dietary items that the patient finds worsen symptoms, elevation of the bed head in those who experience nocturnal symptoms, avoidance of late meals and giving up smoking, should be recommended.

Patients who fail to respond to these measures

should be offered PPIs, which are usually effective

in resolving symptoms and healing oesophagitis.

Recurrence of symptoms is common when therapy is

stopped and some patients require life-long treatment

at the lowest acceptable dose.

Long-term PPI is associated with reduced absorption of iron, B12 and magnesium, and a small increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures , also predispose to infections with Salmonella, Campylobacter and Clostridium difficile.

Increases the risk of Helicobacter-associated progression of gastric mucosal atrophy and H. pylori eradication is advised in patients requiring PPIs for >1 year.

When dysmotility features are prominent, domperidone can be helpful.

There is no evidence that H. pylori eradication has any

therapeutic value.

Proprietary antacids and alginates can also provide symptomatic benefit. H2-receptor antagonist drugs also help symptoms without healing oesophagitis.

Patients who fail to respond to medical therapy, those who are unwilling to take long-term PPIs and those whose major symptom is severe regurgitation should be considered for laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery .

Although heartburn and regurgitation are alleviated in most patients, a small minority develop complications, such as inability to vomit and abdominal bloating (‘gas-bloat’ syndrome’).

Types of hiatus hernia.

Important features of hiatus hernia

The association between gastro- oesophageal reflux disease and asthma

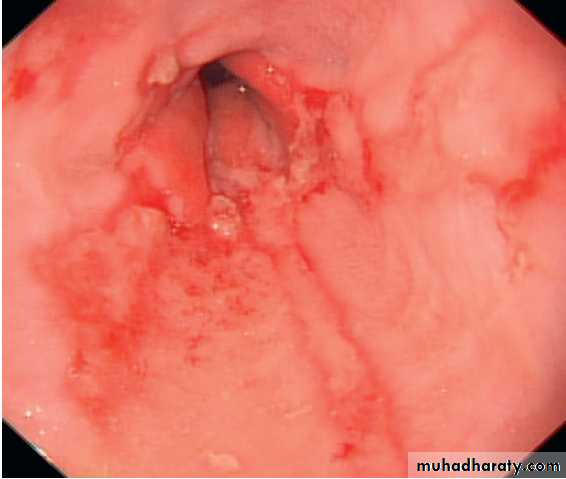

Severe reflux oesophagitis.

There is near-circumferentialsuperficial ulceration and inflammation extending up the gullet.

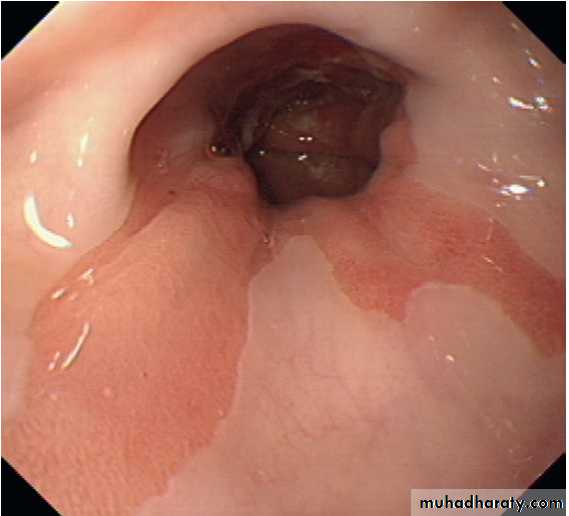

Barrett’s oesophagus.

Tongues of pink columnar mucosa are seen extending upwards above the oesophago-gastric junction.Treatment of gastro- oesophageal reflux disease:

a ‘step-down’ approach.

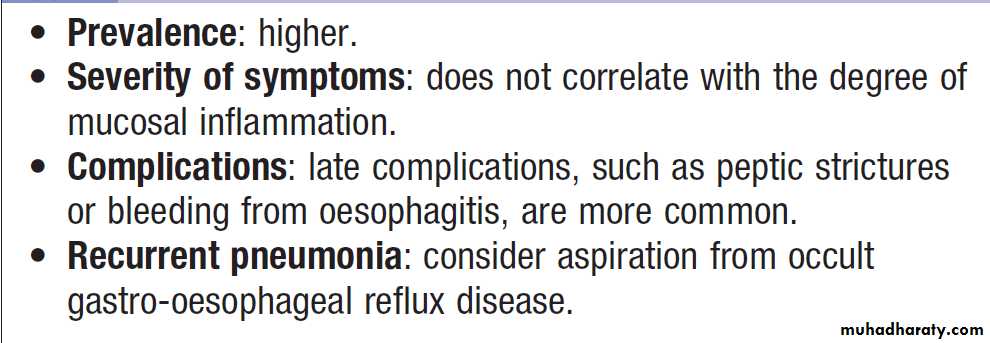

Gastro- oesophageal reflux disease in old age

Other causes of oesophagitisInfection

Oesophageal candidiasis occurs in debilitated patients

and those taking broad-spectrum antibiotics or cytotoxic

drugs. It is a particular problem in patients with HIV.

Corrosives

Suicide attempt by strong household bleach or battery

acid is followed by painful burns of the mouth and

pharynx and by extensive erosive oesophagitis. This may

be complicated by oesophageal perforation with mediastinitis and by stricture formation. At the time of presentation, treatment is conservative, analgesia and nutritional support; vomiting and endoscopy should be avoided because of the high risk of perforation.

After the acute phase, a barium swallow should

be performed to demonstrate the extent of stricture formation. Endoscopic dilatation is usually necessary but it

is difficult and hazardous because strictures are often

long, tortuous and easily perforated.

Drugs

Potassium supplements and NSAIDs may cause

oesophageal ulcers when the tablets are trapped above

an oesophageal stricture. Liquid preparations of these

drugs should be used in such patients. Bisphosphonates

cause oesophageal ulceration and should be used with

caution in patients with known oesophageal disorders.

Motility disorders

Pharyngeal pouchThis occurs because of incoordination of swallowing

within the pharynx, which leads to herniation through

the cricopharyngeus muscle and formation of a pouch.

It is rare, affecting 1 in 100 000 people; it usually develops in middle life but can arise at any age. Many patients have no symptoms, but regurgitation, halitosis and dysphagia can be present. Some notice gurgling in the throat after swallowing.

The investigation of choice is a barium swallow, which demonstrates the pouch and reveals incoordination of swallowing, often with pulmonary aspiration. Endoscopy may be hazardous,

since the instrument may enter and perforate the pouch. Surgical myotomy (‘diverticulotomy’), with or without resection of the pouch, is indicated in symptomatic patients.

Achalasia of the oesophagus

Pathophysiology

Achalasia is characterised by:

• a hypertonic lower oesophageal sphincter, which

fails to relax in response to the swallowing wave

• failure of propagated oesophageal contraction,

leading to progressive dilatation of the gullet.

The cause is unknown. Defective release of nitric

oxide by inhibitory neurons in the lower oesophageal sphincter has been reported, and there is degeneration

of ganglion cells within the sphincter and the body of

the oesophagus.

Infection with Trypanosoma cruzi in Chagas’ disease causes a syndrome that is clinically indistinguishable from achalasia.

Clinical features

Dysphagia, develops slowly, is initially intermittent, and is worse for solids and eased by drinking liquids, and by standing and moving around after eating. Heartburn does not occur because the closed oesophageal sphincter prevents GER. Some experience episodes of chest pain due to oesophageal spasm. As the disease progresses, dysphagia worsens, the oesophagus empties poorly and nocturnal pulmonary aspiration develops. Achalasia predisposes to squamous carcinoma of the oesophagus. InvestigationsEndoscopy should always be carried out because carcinoma of the cardia can mimic the presentation and radiological and manometric features of achalasia (‘pseudo-achalasia’).

A barium swallow shows tapered narrowing of the lower oesophagus and, in late disease, the oesophageal body is dilated, aperistaltic and food-filled . Manometry confirms the high pressure, non-relaxing lower oesophageal sphincter with poor contractility of the oesophageal body .

Management

Endoscopic

Forceful pneumatic dilatation using a 30–35-mm diameter fluoroscopically positioned balloon disrupts the sphincter and improves symptoms in 80%. Some require more than one dilatation but those needing frequent dilatation are best treated surgically. Endoscopically directed injection of botulinum toxin into the lower sphincter induces clinical remission but relapse is common.

Surgical

Surgical myotomy (Heller’s operation), performed either laparoscopically or as an open operation, is effective but is more invasive than endoscopic dilatation. Both pneumatic dilatation and myotomy may be complicated by gastro-oesophageal reflux, and this can lead to severe oesophagitis because oesophageal clearance is so poor.

For this reason, Heller’s myotomy is accompanied by a

partial fundoplication anti-reflux procedure. PPI therapy is often necessary after surgery. Recently, a complex endoscopic technique has been developed in specialist centres (peroral endoscopic myotomy, POEM).

Secondary causes of oesophageal dysmotility

In systemic sclerosis or CREST syndrome, the muscle of the oesophagus is replaced by fibrous tissue, which causes failure of peristalsis leading to heartburn and dysphagia.Oesophagitis is often severe, and benign fibrous strictures occur. These patients require long-term therapy with PPIs.

Dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis and myasthenia gravis may also cause dysphagia.

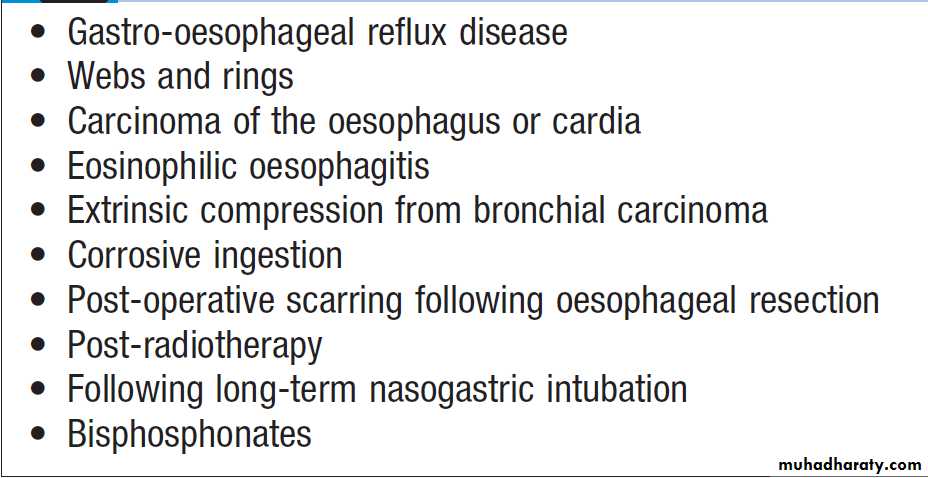

Benign oesophageal stricture

Is usually a consequence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and occurs most often in elderly patients who have poor oesophageal clearance. Rings, due to submucosal fibrosis, are found at the oesophago-gastric junction (‘Schatzki ring’) and cause intermittent dysphagia, often starting in middle age. A post-cricoid web is a rare complication of iron deficiency anaemia (Paterson–Kelly or Plummer–Vinson syndrome), and may be complicated by the development of squamous carcinoma.Benign strictures can be treated by endoscopic dilatation, in which wire guided bougies or balloons are used to disrupt the fibrous tissue of the stricture.

Causes of oesophageal stricture

Tumours of the oesophagusBenign tumours

The most common is a leiomyoma. This is usually

asymptomatic but may cause bleeding or dysphagia.

Carcinoma of the oesophagus

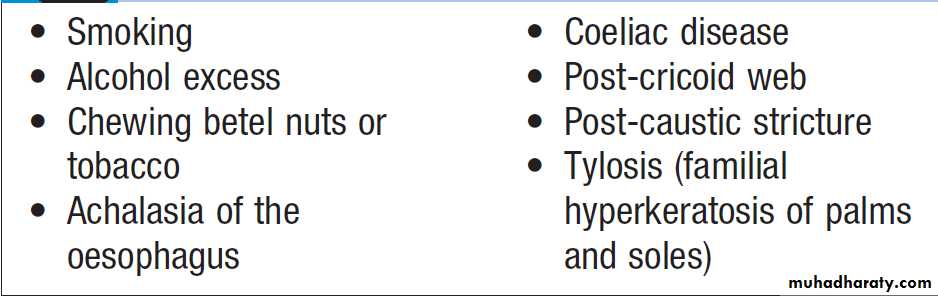

Squamous oesophageal cancer is relatively rare in Caucasians (4 : 100 000) but is more common in Iran, parts of Africa and China (200 : 100 000). Squamous cancer can occur in any part of the oesophagus, and almost all tumours in the upper oesophagus are squamous cancers.

Adenocarcinomas typically arise in the lower third from Barrett’s esophagus or from the cardia of the stomach. Despite modern treatment, the overall 5-year survival of patients presenting with oesophageal cancer is only 13%.

Squamous carcinoma: aetiological factors

Clinical featuresMost patients have a history of progressive, painless

dysphagia for solid foods. Others present acutely

because of food bolus obstruction. In late stages, weight loss is often extreme; chest pain or hoarseness suggests mediastinal invasion. Fistulation between the oesophagus and the trachea or bronchial tree leads to coughing after swallowing, pneumonia and pleural effusion.

Physical signs may be absent but, even at initial presentation, cachexia, cervical lymphadenopathy or other evidence of metastatic spread is common.

Investigations

The investigation of choice is upper endoscopy with biopsy. A barium swallow demonstrates the site and length of the stricture but adds little useful information. Once a diagnosis has been made, investigations should be performed to stage the tumour and define operability. Thoracic and abdominal CT, often combined with positron emission tomography (CT-PET), should be carried out. Invasion of the aorta, major airways or coeliac axis usually precludes surgery, but patients with resectable disease on imaging should undergo EUS to determine the depth of penetration of the tumour into the wall and to detect regional lymph node involvement .Management

The treatment of choice is surgery if the patient presentsat a point at which resection is possible. Patients with

tumours that have extended beyond the wall of the

oesophagus (T3) or which have lymph node involvement

(N1) have a 5-year survival of around 10%.

Overall survival following ‘potentially curative’ surgery (all macroscopic tumour removed) is about 30% at 5 years, but recent studies have suggested that this can be improved by neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Although squamous carcinomas are radiosensitive, radiotherapy alone is associated with a 5-year survival of only 5%, but combined chemoradiotherapy for these tumours can achieve 5-year survival rates of 25–30%.

Approximately 70% of patients have extensive

disease at presentation; in these, treatment is palliative

and should focus on relief of dysphagia and pain. Endoscopic laser therapy or self-expanding metallic stents can be used to improve swallowing.

Palliative radiotherapy may induce shrinkage of both squamous cancers and adenocarcinomas but symptomatic response may be slow.

Quality of life can be improved by nutritional support and appropriate analgesia.

Perforation of the oesophagus

The most common cause is endoscopic perforation complicating dilatation or intubation. Malignant, corrosive or post-radiotherapy strictures are more likely to be perforated than peptic strictures.A perforated peptic stricture is managed conservatively using broad spectrum antibiotics and parenteral nutrition; most cases heal within days.

Malignant, caustic and radiotherapy stricture perforations require resection or stenting.

Spontaneous oesophageal perforation (‘Boerhaave’s

syndrome’) results from forceful vomiting and retching.Severe chest pain and shock occur as oesophago-gastric

contents enter the mediastinum and thoracic cavity.

Subcutaneous emphysema, pleural effusions and pneumothorax develop.

The diagnosis can be made using a water-soluble contrast swallow but, in difficult cases, both CT and careful endoscopy (usually in an intubated patient) may be required.

Treatment is surgical.

Delay in diagnosis is a key factor In the high mortality associated with this condition.

DISEASES OF THE STOMACH AND DUODENUM

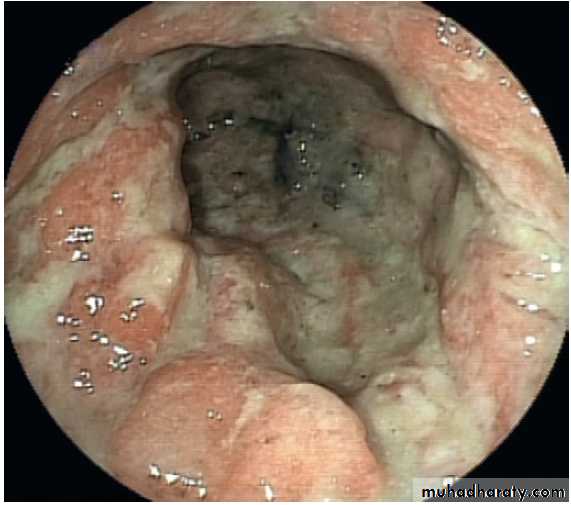

GastritisGastritis is a histological diagnosis, although it can

sometimes be recognised at endoscopy.

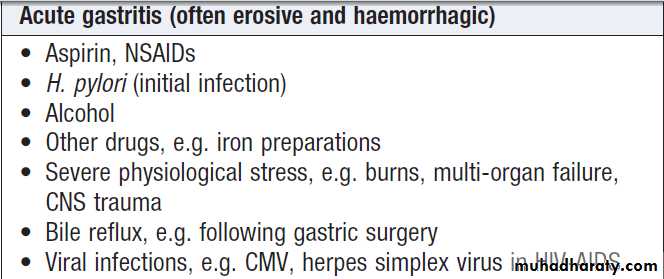

Acute gastritis

Often erosive and haemorrhagic. Neutrophils are the predominant in the superficial epithelium. Many result from aspirin or NSAID ingestion . Often produces no symptoms but may cause dyspepsia, anorexia, nausea , vomiting, haematemesis or melaena. Many cases resolve quickly; in others, endoscopy and biopsy may be necessary to exclude peptic ulcer or cancer. Treatment should be directed at the underlying cause. Short-term symptomatic therapy with antacids, and PPIs, prokinetics (domperidone) or antiemetics (metoclopramide) may be necessary.

Chronic gastritis due to Helicobacter pylori infection

This is the most common cause of chronic gastritis. The predominant inflammatory cells are lymphocytes and plasma cells. Most patients are asymptomatic and do not require treatment, but patients with dyspepsia may benefit from H. pylori eradication.

Autoimmune chronic gastritis

This involves the body of the stomach but spares the

antrum; it results from autoimmune damage to parietal cells. The histological features are diffuse chronic

inflammation, atrophy and loss of fundic glands,

intestinal metaplasia and sometimes hyperplasia of

enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells. Circulating antibodies

to parietal cell and intrinsic factor may be present.

In some patients, the degree of gastric atrophy is severe,

and loss of intrinsic factor secretion leads to perniciousanaemia .The gastritis itself is usually asymptomatic.

Some patients have evidence of other organspecific

autoimmunity, particularly thyroid disease. Long-term, there is a two- to threefold increase in the risk of gastric cancer . Ménétrier’s disease

In this rare condition, the gastric pits are elongated and tortuous, with replacement of the parietal and chief cells by mucus-secreting cells. The cause is unknown but there is excessive production of TGF-α. As a result, the mucosal folds of the body and fundus are greatly enlarged.

Most patients are hypochlorhydric.

Whilst some have upper Gl symptoms, majority present in middle or old age with protein losing enteropathy due to exudation from the gastric mucosa.

Endoscopy shows enlarged, nodular and coarse folds, although biopsies may not be deep enough to show all the histological features.

Treatment with antisecretory drugs, such as PPIs with or without octreotide, may reduce protein loss and H. pylori eradication may be effective, but unresponsive patients require partial gastrectomy.

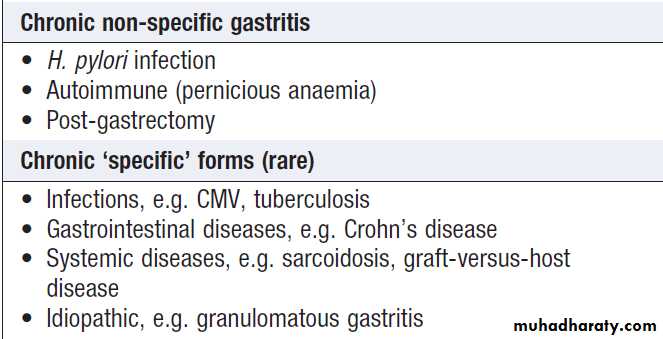

Common causes of gastritis

Peptic ulcer disease

The term ‘peptic ulcer’ refers to an ulcer in the loweroesophagus, stomach or duodenum, in the jejunum after

surgical anastomosis to the stomach or, rarely, in the

ileum adjacent to a Meckel’s diverticulum. Ulcers in the

stomach or duodenum may be acute or chronic; both

penetrate the muscularis mucosae but the acute ulcer

shows no evidence of fibrosis. Erosions do not penetrate

the muscularis mucosae. Peptic ulcer disease is a chronic condition with spontaneous relapses and remissions lasting for decades, if not for life.

The most common presentation is with recurrent abdominal pain which has three notable characteristics: localisation to the epigastrium, relationship to food and episodic occurrence.

Gastric and duodenal ulcer

The prevalence of peptic ulcer (0.1–0.2%) is decreasingin many Western communities as a result of widespread

use of Helicobacter pylori eradication. The male-to-female

ratio for duodenal ulcer varies from 5 : 1 to 2 : 1,

whilst that for gastric ulcer is 2 : 1 or less. Chronic gastric

ulcer is usually single; 90% are situated on the lesser

curve within the antrum or at the junction between body

and antral mucosa. Chronic duodenal ulcer usually

occurs in the first part and 50% are on the anterior wall. Gastric and duodenal ulcers coexist in 10% of patients and more than one peptic ulcer is found in 10–15%.

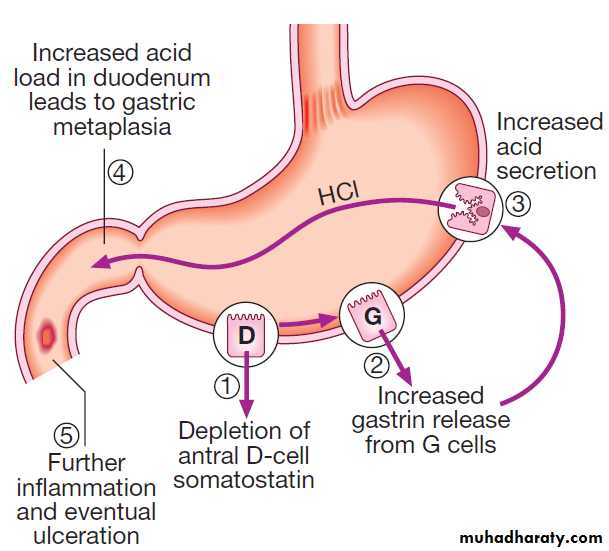

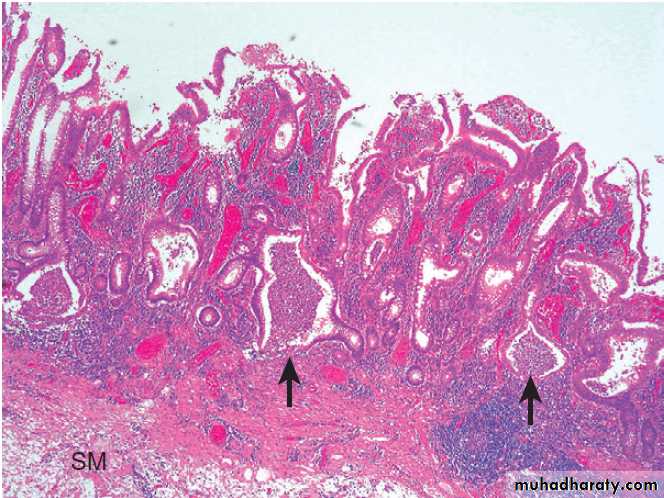

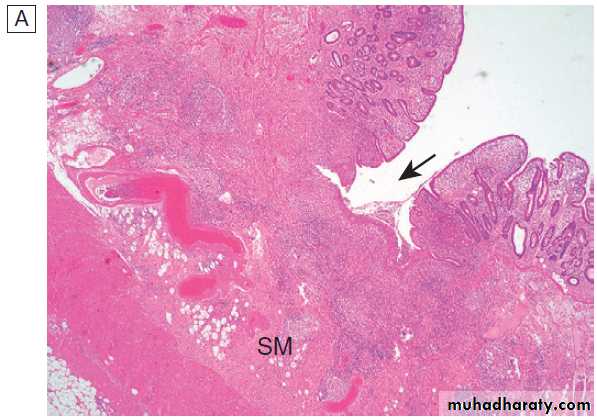

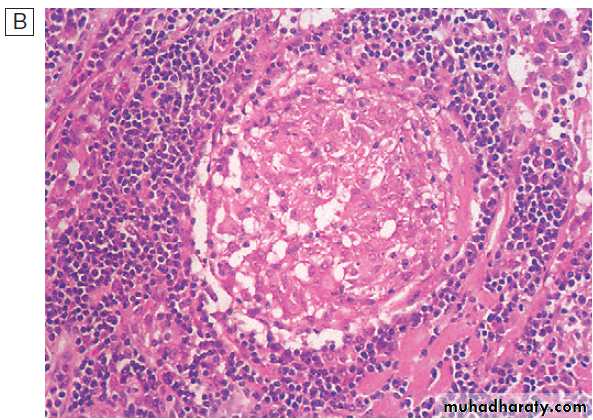

Sequence of events in the pathophysiology of

duodenal ulceration.Consequences of H. pylori infection

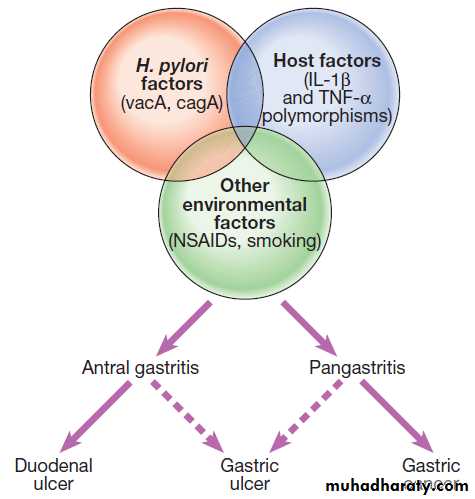

PathophysiologyH. pylori

Peptic ulceration is strongly associated with H. pylori

infection. The prevalence in developed nations rises

with age, and in the UK approximately 50% over the age of 50 years are infected. In the developing world, infection is more common, affecting up to 90% of adults. These infections are probably acquired in childhood by person-to-person contact. The vast majority of colonised people remain healthy and asymptomatic. Around 90% of duodenal ulcer patients and 70% of gastric ulcer patients are infected with H. pylori. The remaining 30% of gastric ulcers are caused by NSAIDs.

H. pylori is Gram-negative and spiral, and has multiple

flagella at one end, which make it motile, allowingit to burrow and live beneath the mucus layer adherent

to the epithelial surface. It uses an adhesin molecule

(BabA) to bind to the Lewis b antigen on epithelial cells.

Here the surface pH is close to neutral and any acidity

is buffered by the organism’s production of the enzyme

urease. This produces ammonia from urea and raises the

pH around the bacterium and between its two cell membrane layers. H. pylori exclusively colonises gastric-type epithelium and is only found in the duodenum in association with patches of gastric metaplasia. It causes chronic gastritis by provoking a local inflammatory response in the underlying epithelium .

In most people, H. pylori causes localised antral gastritis

associated with depletion of somatostatin (from D

cells) and increased gastrin release from G cells. The

subsequent hypergastrinaemia stimulates increased acid

production by parietal cells but, in the majority of cases,

this has no clinical consequences. In a minority of

patients, this effect is exaggerated, leading to duodenal

ulceration . In 1% of infected people, H. pylori

causes a pangastritis, leading to gastric atrophy and

hypochlorhydria. This allows other bacteria to proliferate

within the stomach; these produce mutagenic nitrites

from dietary nitrates, predisposing to the development

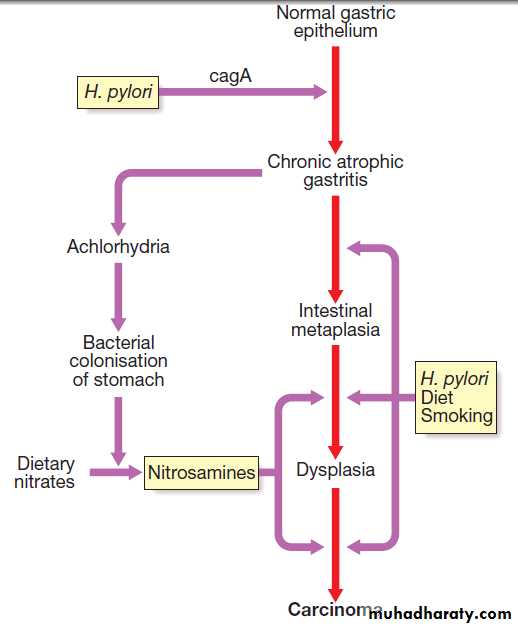

of gastric cancer .

The effects of H. pylori are more complex in gastric ulcer patients compared to those with duodenal ulcers. The ulcer probably arises because of impaired mucosal defence resulting from a combination of H. pylori infection, NSAIDs and smoking, rather than excess acid.

NSAIDs

Treatment with NSAIDs is associated with peptic ulcers

due to impairment of mucosal defences.

Smoking

Smoking confers an increased risk of gastric ulcer and,

to a lesser extent, duodenal ulcer. Once the ulcer has

formed, it is more likely to cause complications and less

likely to heal if the patient continues to smoke.

Clinical features

Peptic ulcer disease is a chronic condition with spontaneous relapses and remissions lasting for decades, if not for life.The most common presentation is with recurrent

abdominal pain which has three notable characteristics:

localisation to the epigastrium, relationship to food and

episodic occurrence. Occasional vomiting occurs in

about 40% of ulcer subjects; persistent daily vomiting

suggests gastric outlet obstruction. In one-third, the

history is less characteristic, especially in elderly people

or those taking NSAIDs. In them, pain may be absent or

so slight that it is experienced only as a vague sense of

epigastric unease. Occasionally, the only symptoms are

anorexia and nausea, or early satiety after meals .

In some patients, the ulcer is completely ‘silent’, presenting

for the first time with anaemia from chronic undetectedblood loss, as an abrupt haematemesis or perforation; in others, there is recurrent acute bleeding without ulcer pain. The history is therefore a poor predictor of the presence of an ulcer.

Investigations

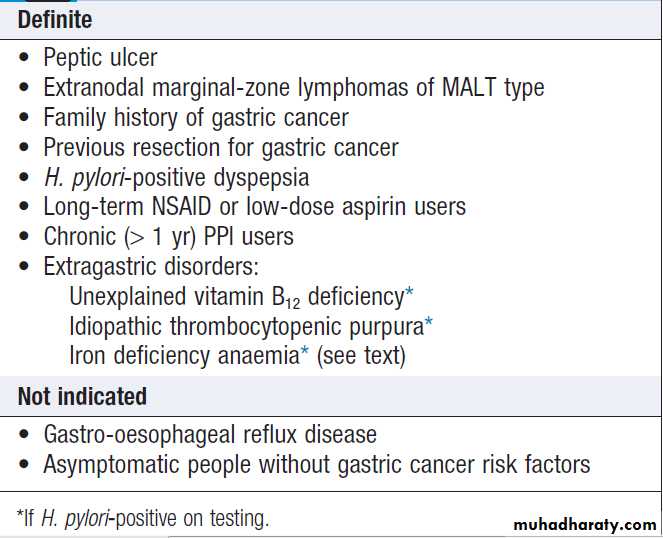

Endoscopy is the preferred investigation. Gastric ulcers

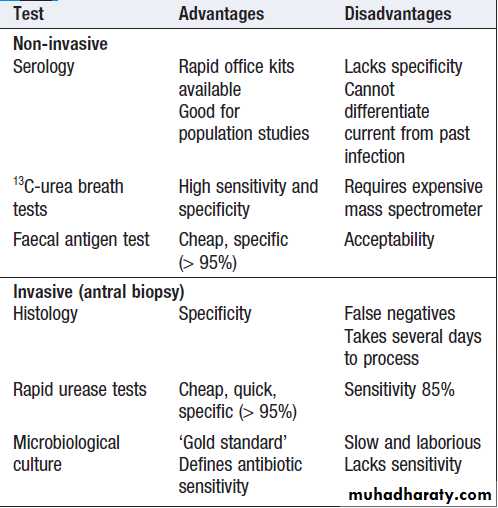

may occasionally be malignant and must always be biopsied and followed up to ensure healing. Patients should be tested for H. pylori infection. Some are invasive and require endoscopy; others are noninvasive. They vary in sensitivity and specificity. Breath or faecal antigen tests are best because of accuracy, simplicity and non-invasiveness.

Management

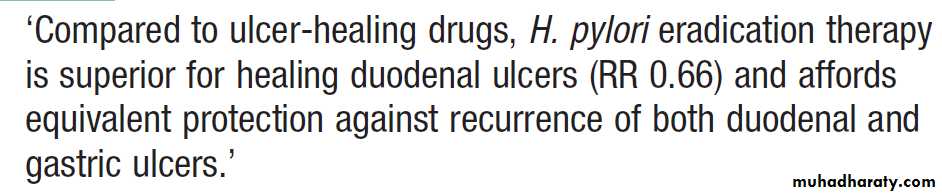

The aims of management are to relieve symptoms, induce healing and prevent recurrence. H. pylori eradication is the cornerstone of therapy for peptic ulcers, as this will successfully prevent relapse and eliminate the need for long-term therapy in the majority of patients.H. pylori eradication

All patients with proven ulcers who are H. pylori-positive

should be offered eradication as primary therapy. Treatment is based upon a PPI taken simultaneously with two antibiotics (from amoxicillin, clarithromycin and metronidazole) for 7 days . High-dose, twice-daily

PPI therapy increases efficacy of treatment, as does

extending treatment to 10–14 days.

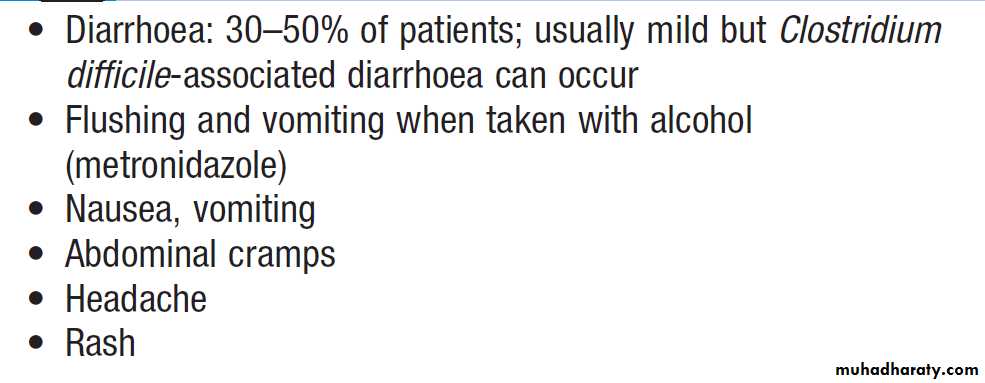

Success is achieved in 80–90% of patients, although compliance, side-effects and antibiotic resistance influence this. Resistance to amoxicillin is rare but rates of metronidazole resistance reach 40% in some countries and, recently, rates of clarithromycin resistance of 20–40% have appeared.

Where the latter exceed 15–20%, a quadruple therapy regimen, consisting of omeprazole (or another PPI), bismuth subcitrate, metronidazole and tetracycline (OBMT) for 10–14 days, is recommended.

In areas of low clarithromycin resistance, this regimen should also be offered as second-line therapy to those who remain infected after initial therapy, once compliance has been checked.

For those who are still colonised after two treatments,

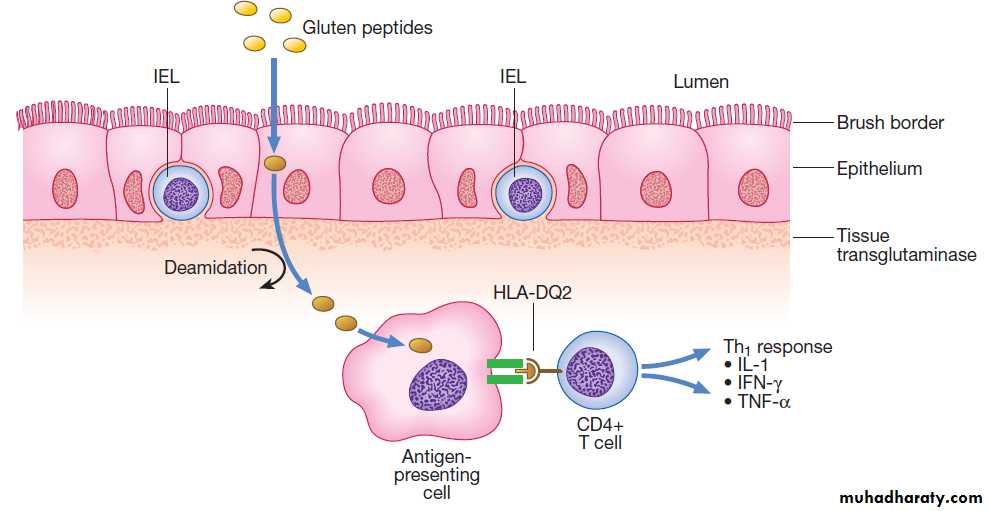

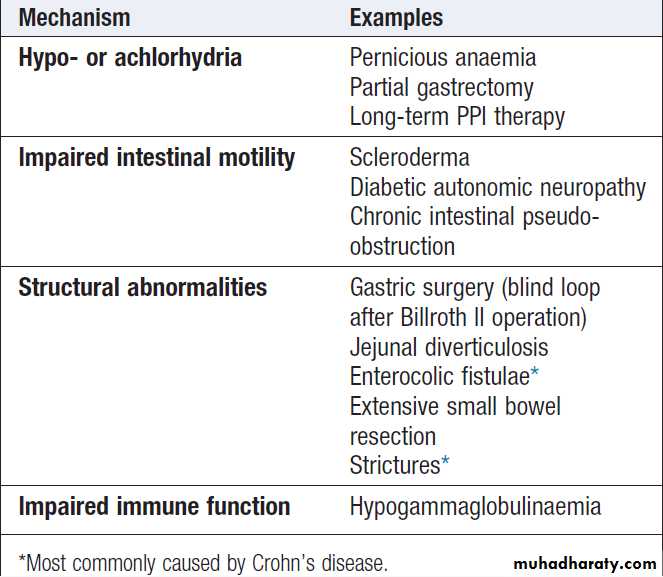

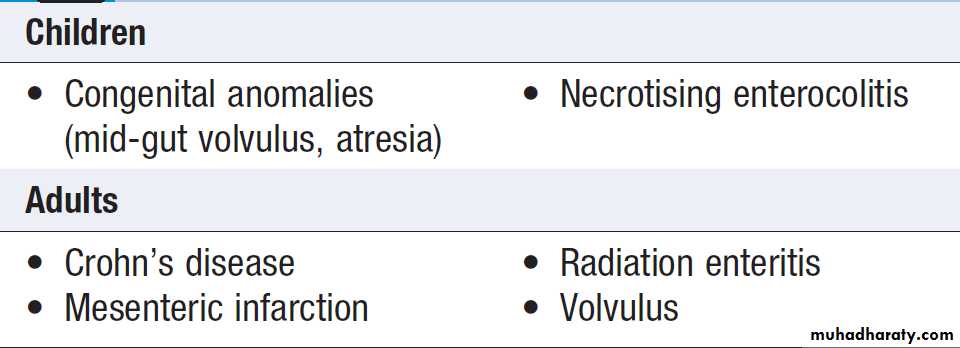

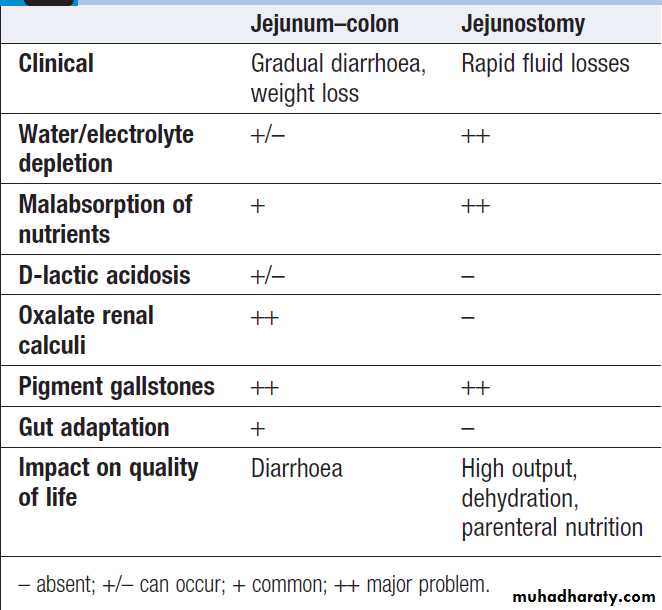

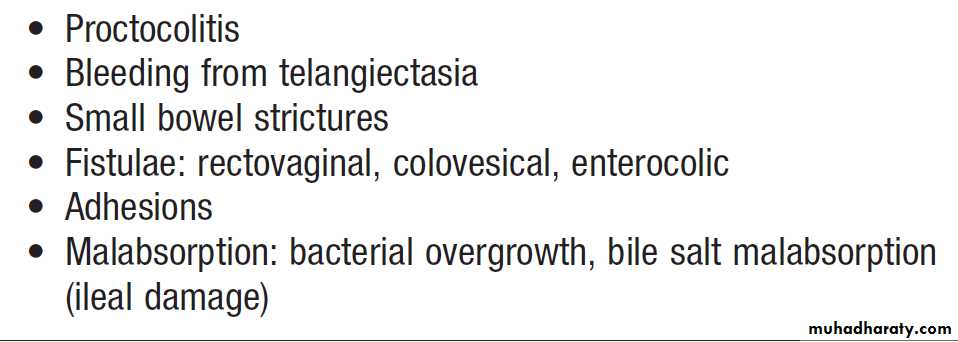

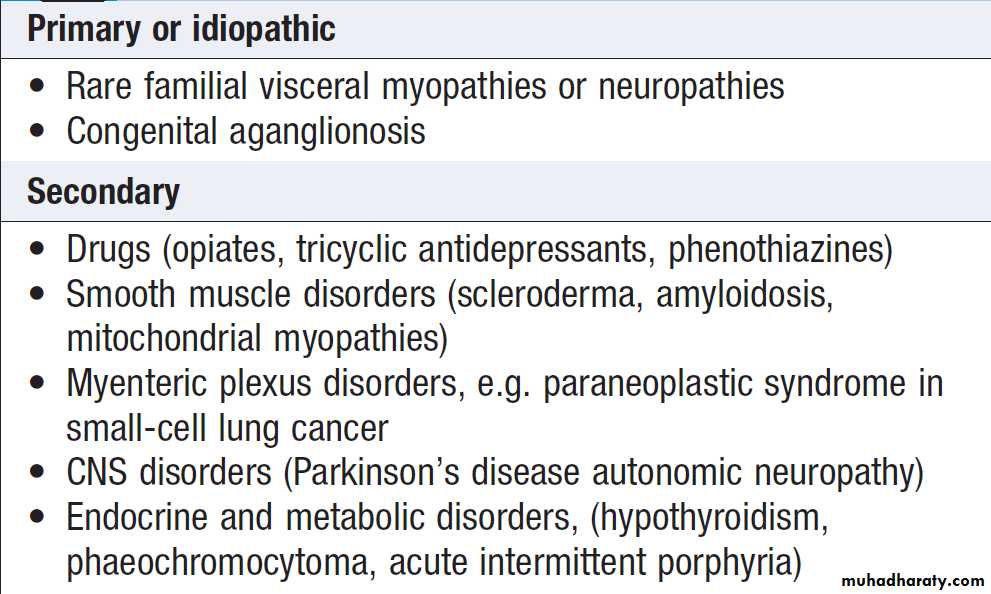

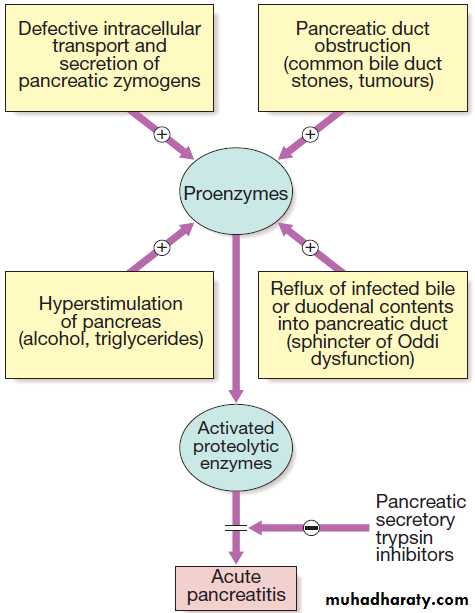

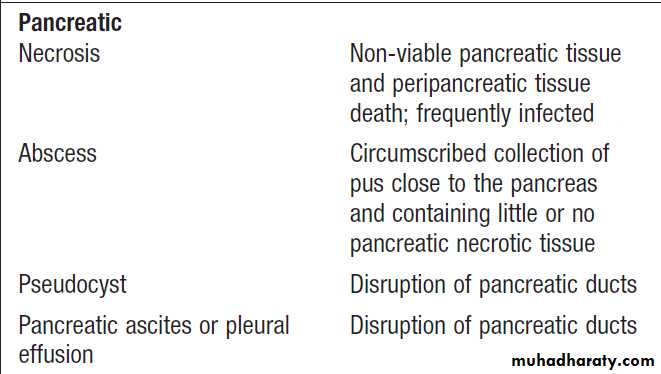

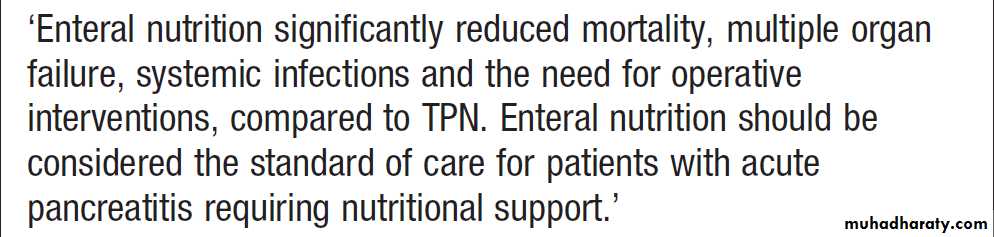

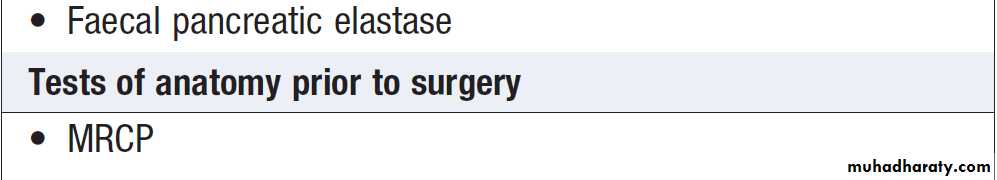

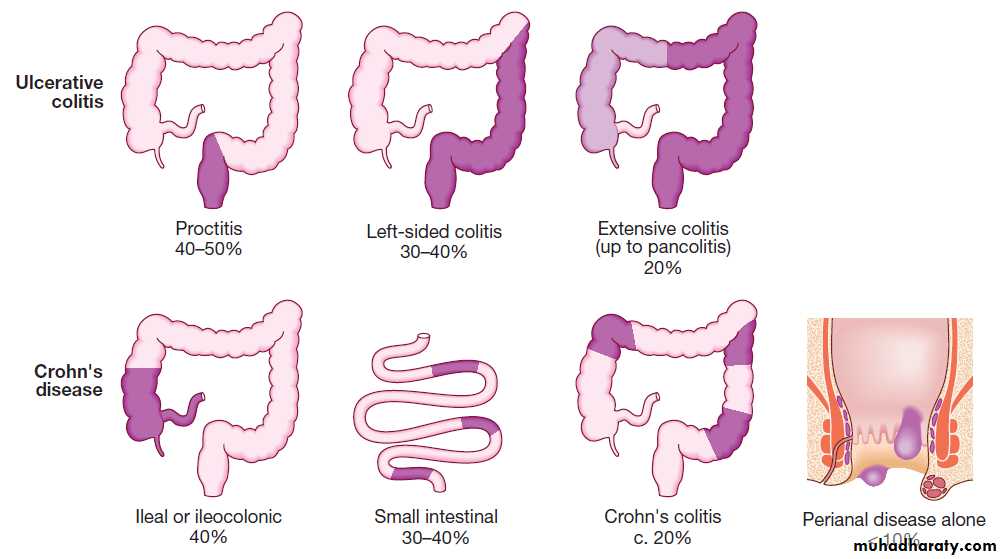

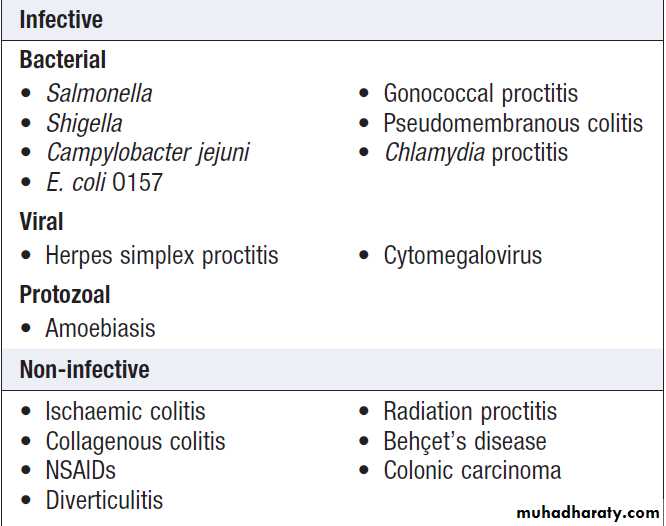

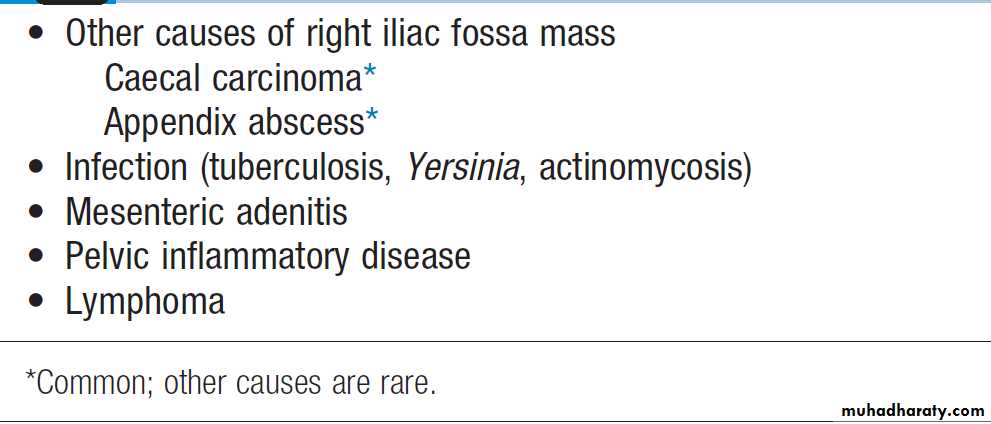

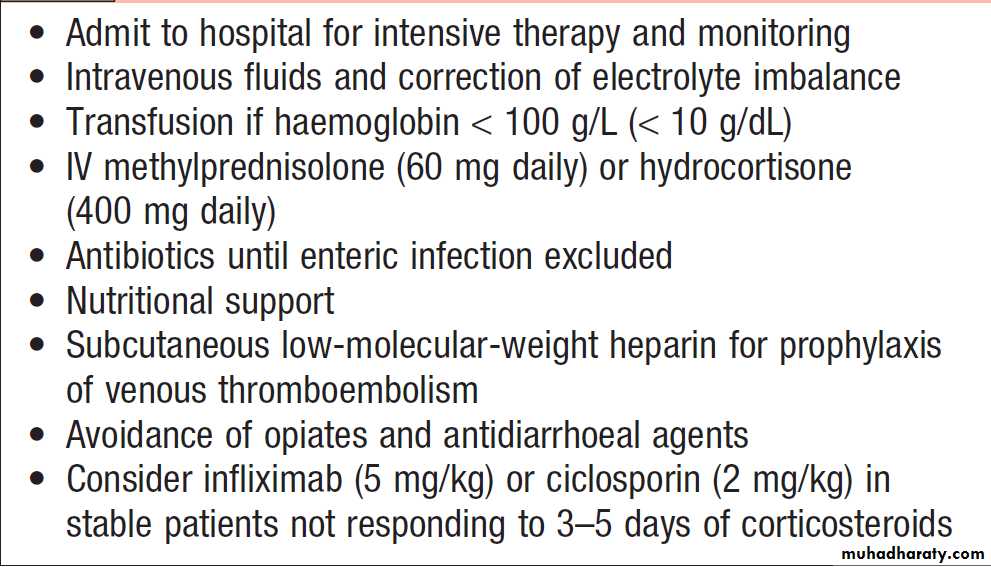

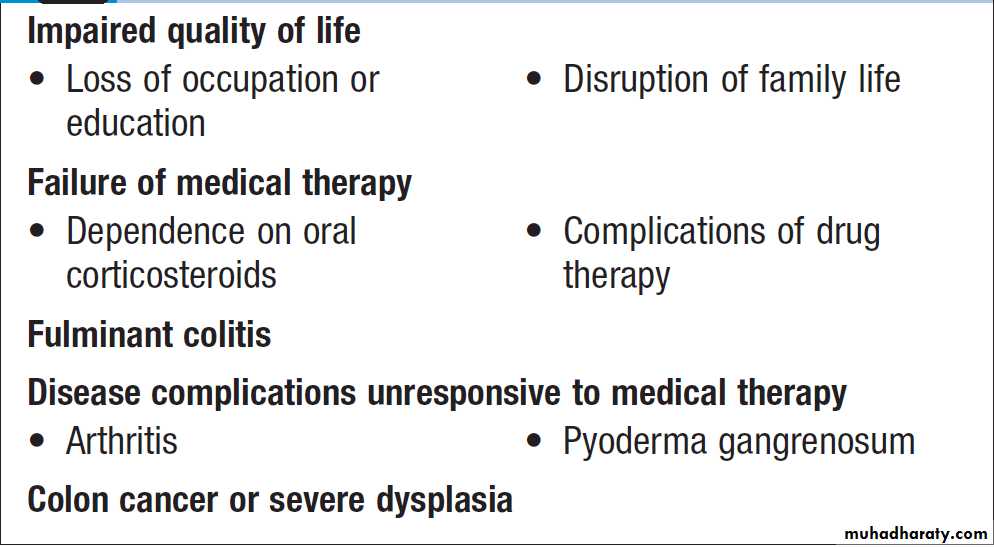

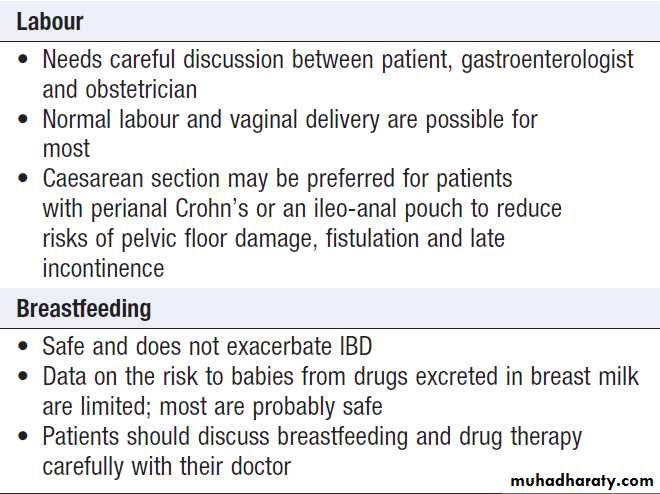

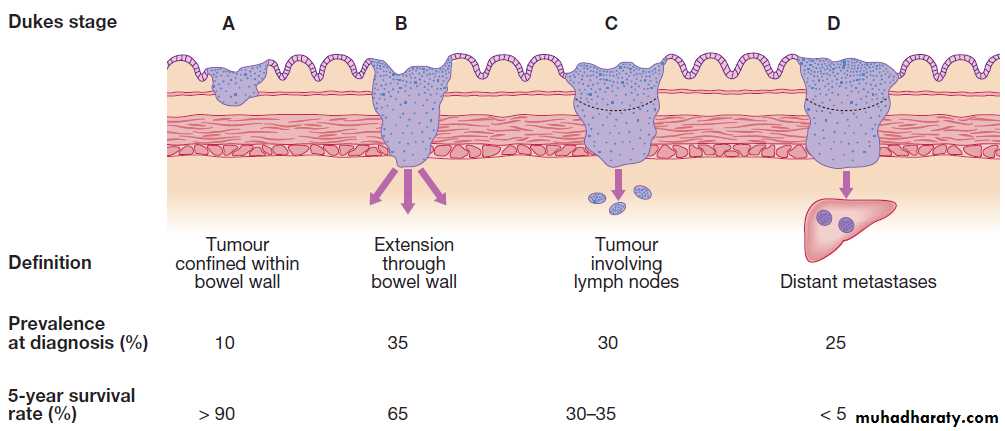

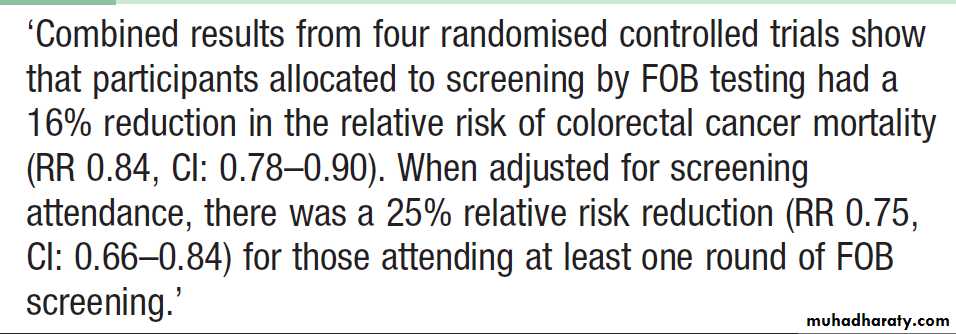

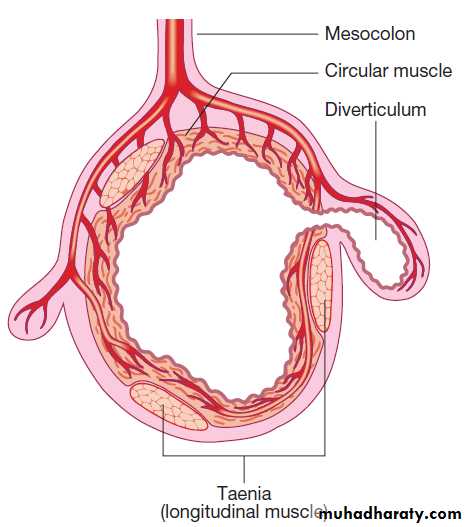

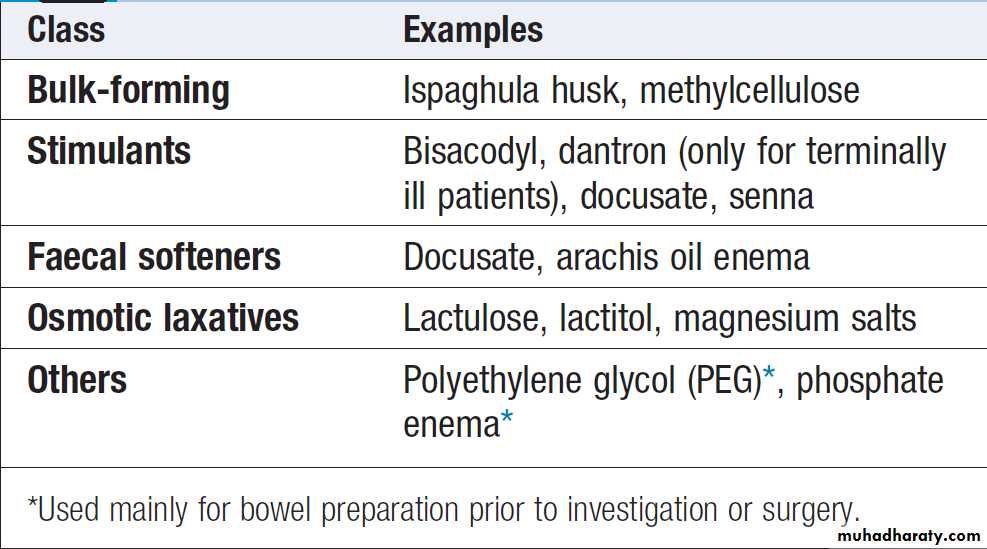

the choice lies between a third attempt guided bysensitivity testing, rescue therapy (levofloxacin, PPI and clarithromycin) or long-term acid suppression.